Summary

The etiologic agent of Lyme disease, Borrelia burgdorferi, is transmitted via infected Ixodes spp. ticks. Infection, if untreated, results in dissemination to multiple tissues and significant morbidity. Recent developments in bioluminescence technology allow in vivo imaging and quantification of pathogenic organisms during infection. Herein, luciferase-expressing B. burgdorferi and strains lacking the decorin adhesins DbpA and DbpB, as well as the fibronectin adhesin BBK32, were quantified by bioluminescent imaging to further evaluate their pathogenic potential in infected mice. Quantification of bacterial load was verified by quantitative PCR (qPCR) and cultivation. B. burgdorferi lacking DbpA and DbpB were only seen at the 1 h time point post-infection, consistent with its low infectivity phenotype. The bbk32 mutant exhibited a significant decrease in its infectious load at day 7 relative to its parent. This effect was most pronounced at lower inocula and imaging correlated well with qPCR data. These data suggest that BBK32-mediated binding plays an important role in B. burgdorferi colonization. As such, in vivo imaging of bioluminescent Borrelia provides a sensitive means to detect, quantify, and temporally characterize borrelial dissemination in a non-invasive, physiologically relevant environment and, more importantly, demonstrated a quantifiable infectivity defect for the bbk32 mutant.

Introduction

Initial infection by the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi is characterized by a flu-like illness accompanied by a painless skin rash denoted as erythema migrans (Steere et al., 2004; Nadelman and Wormser, 1998). Following infection, B. burgdorferi disseminates throughout the host and resides in locales that apparently provide an immunoprotected niche. The resulting infection can give rise to cardiac, neurologic, and arthritic manifestations that, when not treated therapeutically with antibiotics, can contribute to significant morbidity (Steere et al., 2004; Nadelman and Wormser, 1998; Stanek and Strle, 2003).

In the past, the use of the mouse model of infection has been key to understanding various aspects of Lyme borreliosis (reviewed recently in Barthold et al., 2010). More recently, the advent of genetic tools to isolate isogenic mutants in B. burgdorferi now allows one to evaluate the importance of a given gene during experimental infection (Rosa et al., 2005, 2010). Although the mouse has provided both qualitative and quantitative data to follow the infectious process of both wild type and mutant B. burgdorferi, the ability to readily visualize spirochetes during active infection has been difficult. Despite the fact that tissues from infected animals are culture positive, the ability to detect B. burgdorferi in these same tissues has not been forthcoming presumably due to low numbers, as well as the wave-like morphology and narrow diameter of these organisms, which make detection via either confocal or electron microscopy difficult. Recently, two separate reports detected fluorescent B. burgdorferi in real time within the vasculature of infected mice using quantitative real-time intravital microscopy (Moriarty et al., 2008; Norman et al., 2008). Although extremely valuable given that B. burgdorferi were detected at high resolution in vivo, technical aspects limit the imaging plane such that only a small area can be visualized. Coincident with this issue, the detection of spirochetes within the bloodstream was dependent on large intravenous doses.

The use of in vivo imaging has been adapted to globally track various target cell types as well as the infectious potential of a number of pathogens that have been modified to display fluorescence or bioluminescence (Kong et al., 2011; Francis et al., 2001; Burns et al., 2001; Contag et al., 1995; Francis et al., 2000; Edinger et al., 2002; Rhee et al., 2010). This technology has the advantage of allowing temporal and spatial evaluation of an infectious process in a non-invasive manner whereby the same animal in its entirety can been analyzed (under anesthesia) at numerous times throughout an experiment. Thus, this approach allows detailed analysis of the establishment and maintenance of infection as well as kinetic studies.

To determine whether bioluminescent B. burgdorferi could be detected and tracked following infection, we transformed strains with a borrelial codon-optimized version of firefly luciferase (luc) (Blevins et al., 2007) and infected mice via needle inoculation with both parent and mutant strains that are impaired in their ability to recognize either host fibronectin or decorin. The results obtained suggest that in vivo imaging can be exploited to track B. burgdorferi infection. This conclusion is supported by the fact that the images obtained displayed a strong correlation with other quantitative measures of infection. As such, biophotonic imaging technology provides a powerful and non-invasive method to track dissemination of B. burgdorferi following experimental infection and provides an additional and novel modality to assess whether a given mutant derivative is impaired in terms of colonization and/or dissemination.

Results

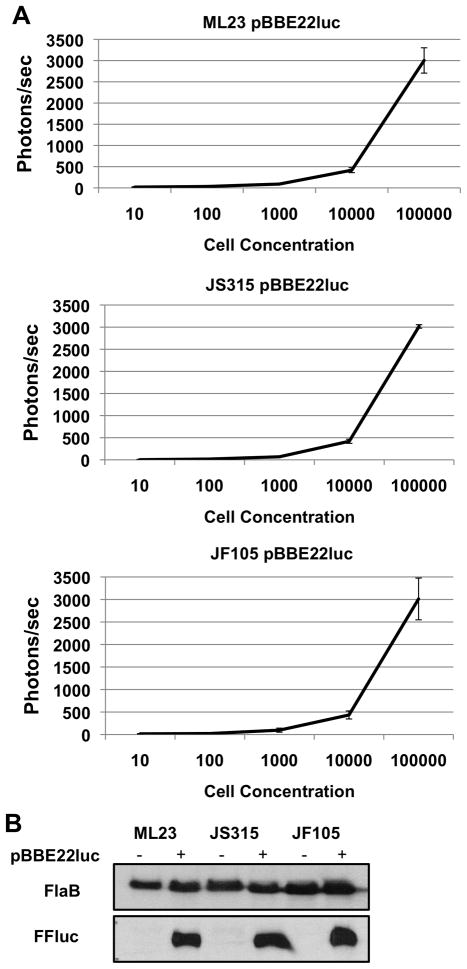

In vitro detection of live luminescent B. burgdorferi

The initial description by Blevins et al. of the borrelial codon optimized firefly luciferase (luc) was as an in vitro transcriptional reporter in B. burgdorferi (Blevins et al., 2007). The high sensitivity of this system suggested that luciferase would be a useful reporter for optical imaging in live animals. The B. burgdorferi parent strain ML23 (Labandeira-Rey and Skare, 2001), as well as mutant derivatives in either bbk32 (bbk32:: StrR; strain JS315; (Seshu et al., 2006)) or both dbpA and dbpB (ΔdbpBA::GentR; strain JF105; (Weening et al., 2008)), were transformed with the shuttle vector pBBE22-gate containing constitutively expressed luc (pBBE22luc). The resulting transformants were grown in vitro in BSK-II media, incubated with D-luciferin, and their ability to produce light was measured following 10-fold serial dilutions of 106 B. burgdorferi down to 10 cells. Expression of luc and treatment with D-luciferin did not impair borrelial cell motility or viability in vitro (data not shown). Negligible background was detected in B. burgdorferi lacking the luc gene and B. burgdorferi that constitutively expressed luc did not emit detectable light in the absence of added substrate (data not shown). Furthermore, B. burgdorferi lacking luc and provided D-luciferin did not emit detectable light above background levels (data not shown). Background levels from controls ranged between 64–80 photons/sec, which were comparable to levels seen for 10 borrelial cells, independent of the strain assessed (Fig. 1A). For 102 and 103 B. burgdorferi, light emission was between 56–104 photons/sec and 84–232 photons/sec, respectively, indicating that the threshold for detection (after accounting for background) was between 102 and 103 spirochetes. The results obtained indicated that there was no significant difference in light production for any of the strains tested at each of the cell concentrations tested (Fig. 1A). The ability of the B. burgdorferi strains to produce Luc protein was evaluated and all three strains containing the luc construct synthesized identical levels of Luc protein when evaluated by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 1B), consistent with the comparable levels of Luc-dependent activity observed between all three strain tested (Fig 1A).

Figure 1. Luminescence of in vitro cultivated B. burgdorferi.

(A) Equivalent light is produced for all strains tested. Borrelial strains ML23 pBBE22luc, JS315 pBBE22luc, and JF105 pBBE22luc were grown to mid-log phase and serially diluted from 105 to 10 cells and incubated with D-luciferin. Luminescence was measured for each sample after subtracting the background levels observed in complete BSK-II media. Cultures for all strains were grown in triplicate and the resulting luminescent values were averaged. (B) Comparable amounts of Luciferase protein are produced by all strains tested. Protein lysates from B. burgdorferi strains with and without pBBE22luc were tested for the production of firefly luciferase (FFluc). Samples were immunoblotted and probed with anti-sera to antigen indicated on the left. Constitutively produced borrelial FlaB was used as a control for cell equivalents between samples.

In vivo detection of B. burgdorferi following short-term infection

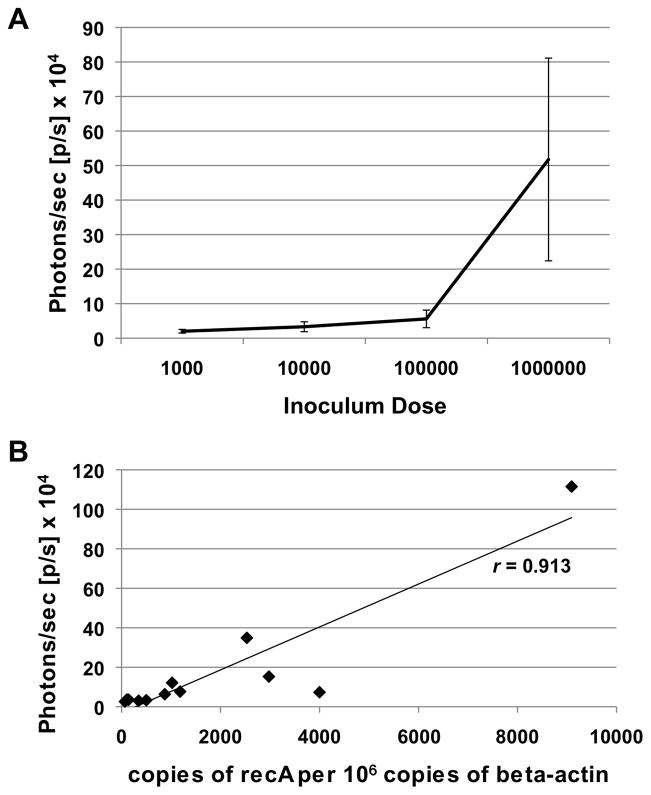

The sensitivity of luc-expressing B. burgdorferi was evaluated in vivo by infecting mice intradermally with 10-fold serial dilutions of B. burgdorferi from 106 to 103 bacteria. Balb/c mice were used, since the absence of melanin in albino mice reduces interference with light emission allowing for a stronger and more representative Luc-mediated signal. One hour post-infection, the mice were administered luciferin, imaged for 1 minute, and quantitatively assessed for photon emission. The mice were then sacrificed and skin removed at each site of inoculation. An early time point was used, prior to innate host clearance and borrelial dissemination, to evaluate recovery of known amounts of B. burgdorferi from infected tissue. These samples were normalized to comparable samples taken from uninfected mice given D-luciferin. The amplitude of light signal in the mouse skin was proportional to levels observed in vitro (Fig. 1A) and demonstrated a comaprable degree of sensitivity, such that 103 spirochetes fell within the threshold of detection (Fig. 2A). This is difficult to resolve from the data shown due to the amplitude of the 106 dose. However, the normalized values for mice infected at a dose of 103 averaged 2 × 104 photons/sec (+/− 0.53 × 104 p/s), a value that is well above background levels. Consistent with the signal observed from in vitro cultivated spirochetes (Fig. 1A), there was a linear relationship between bioluminescence and spirochete numbers from higher concentrations of spirochetes down to 104 spirochetes (Fig. 2A). The skin samples were processed, B. burgdorferi genomic equivalents detected by quantitative PCR (qPCR) and compared with luminescence (photons/sec). These data demonstrated a strong correlation in flux relative to spirochete load (r = 0.913; Fig. 2B), indicating that optical imaging is a valid technique to quantify B. burgdorferi in skin tissue at early time points.

Figure 2. In vivo luminescence detection of known amounts of borrelial cells.

Balb/c mice were infected by intradermal injection with ML23 pBBE22luc at the doses indicated. (A) Light detection in vivo. Following 1 h of infection, mice were treated with D-luciferin, imaged for 1 min and luminescence in photons per second [p/s] was measured for each dose indicated. Infection was performed in triplicate and the region of interest (ROI) was defined to measure the luminescence at the specific site of inoculation. Luminescence measurements were normalized by subtracting background measurement from an uninfected mouse treated with D-luciferin and imaged with the infected mice. Luminescence values were averaged and bars on the graphs represent standard error. (B) Correlation of infection dose with light emission. Borrelial genomic equivalents from mice infected with 103, 104, 105, and 106 ML23 pBBE22luc were determined by qPCR from inoculation site skin samples. Copies of B. burgdorferi recA per 106 copies of beta-actin were calculated for each dose in triplicate. Corresponding luminescence values [p/s] and borrelial genomic equivalents were plotted and yielded a correlation (r value) of 0.913.

In vivo imaging can track B. burgdorferi infection in a temporal and spatial manner

The B. burgdorferi B31 derivative ML23 pBBE22luc was used as the infectious parent for all of the strains evaluated herein. Strain ML23 lacks the 25 kb linear plasmid (lp25), which is essential for borrelial replication during infection (Labandeira-Rey and Skare, 2001; Labandeira-Rey et al., 2003; Purser and Norris, 2000). The presence of the bbe22 and bbe23 genes on pBBE22luc complements the lp25-specific infectivity defect of ML23 and restores infectivity to wild type levels following intradermal needle inoculation (Purser et al., 2003) while the addition of the PflaB-luc provides constitutive expression of the borrelial codon optimized firefly luciferase (Blevins et al., 2007). Furthermore, the presence of bbe22 on the shuttle vector provides a positive selection for maintenance of this plasmid in the lp25 deficient background, ensuring that all live borrelial cells will emit light in vivo. Balb/c mice were infected with 101, 102, 103, 104 or 105 ML23 pBBE22luc and a 1 minute exposure was measured for luminescence after injection of D-luciferin at 1 h and 1, 4, 7, 10 and 14 days to determine the threshold of detection by imaging throughout the course of infection with B. burgdorferi (Fig. S1). On day 7, inoculum doses of 104 and 105 were significantly different from all other tested doses resulting in a P value of 0.02 or less in each comparison. ML23 pBBE22luc at doses of 102 and 103 were detectable but lacked significant difference relative to each other at the peak of infection on day 7 (Fig. S1). Based on these results, we defined a low and high inoculum dose as 103 and 105 spirochetes, respectively. It is important to note that we observed no overt difference in infectivity in the luc containing parent strain of B. burgdorferi (i.e., ML23 pBBE22luc) relative to the same strains lacking luc (i.e., ML23 pBBE22), indicating that the production of luciferase does not have an adverse effect on B. burgdorferi during the infectious process (data not shown).

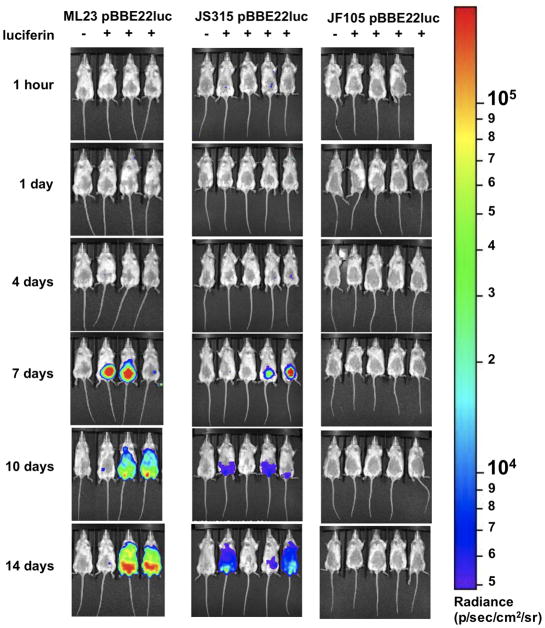

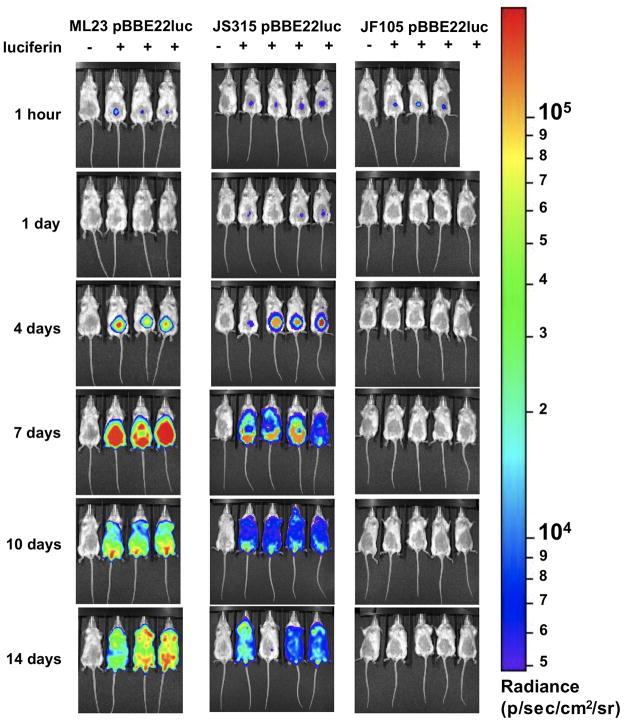

To further evaluate the progression of B. burgdorferi infection over time in live mice, we infected mice intradermally with doses of 103 to 105 spirochetes. In addition to the ML23 parent strain, we tested the bbk32 knockout strain JS315 (Seshu et al., 2006) and dbpBA deletion derivative JF105 (Weening et al., 2008), both containing pBBE22luc. Mice were randomly selected for imaging, treated with D-luciferin, and 1 and 10 minute luminescence measurements were obtained for quantitative and visual analyses, respectively. Each panel shown, for each day analyzed, represents a 10 minute luminescence exposure from an independent group of mice, which were then sacrificed to evaluate both qualitative (cultivation) and quantitative (qPCR) measures of infection. The first mouse on the left is infected with the designated B. burgdorferi strain and dose, but was not administered the D-luciferin substrate to serve as a control for background luminescence (Fig. 3 and 4). Likewise, when mice were infected with ML23 pBBE22 without luc and given substrate, these mice exhibited background comparable to the control mice shown in Fig. 3 and 4 (data not shown).

Figure 3. Temporal and spatial tracking of B. burgdorferi strains following infection with 103 spirochetes.

Balb/c mice were infected with ML23 pBBE22luc, JS315 pBBE22luc or JF105 pBBE22luc at a dose of 103. Mice were selected randomly and treated with D-luciferin 1 h and 1, 4, 7, 10 and 14 days post infection for in vivo imaging. Images represent independent infections because mice were sacrifice beginning on day 4 and thereafter for cultivation and qPCR analyses. For each image shown the mouse on the far left was infected with B. burgdorferi but did not receive D-luciferin to serve as a background control. An image was obtained using a 10 min exposure. All images from each time point and strain were normalized to the same photons/sec range of 1.82×103 to 4.8×105 and displayed on the same color spectrum scale (right).

Figure 4. Temporal and spatial tracking of B. burgdorferi strains following infection with 105 spirochetes.

Balb/c mice were infected with ML23 pBBE22luc, JS315 pBBE22luc or JF105 pBBE22luc at a dose of 105 and imaged as described in the Figure 3 legend. Note that the same color spectrum scale used is between the two doses tested.

Low level luminescence was detected 1 h post-infection at a dose of 105 spirochetes for all strains tested regardless of mutation and is markedly reduced after 24 h, suggesting that the majority of the B. burgdorferi injected are killed and/or disseminate by this time point (Fig. 4). The possibility that a good portion of the borrelial cells are killed early in the infectious process is supported by several studies that evaluate in vitro and in vivo approaches to assess B. burgdorferi processing by the innate immune response (recently reviewed in Weis and Bockenstedt, 2010).

The dbpBA deletion strain showed no detectable spirochetes except immediately following inoculation for mice infected with 105 organisms (Fig 4). At no other time point were spirochetes visible in B. burgdorferi deleted for dbpBA, consistent with the severely attenuated phenotype associated with cells lacking DbpBA (Weening et al., 2008; Blevins et al., 2008; Shi et al., 2008). In stark contrast to the dbpBA deletion strain, the parent strain exhibit the highest degree of colonization as measured by photon emission at all doses tested (Fig 3 and 4). Bioluminescence is readily observed in the parent strain 4 days post infection at inocula of 105 and by day 7 when 103 B. burgdorferi cells were used for the initial infection. Over time, the infection spreads throughout the skin at the higher inoculum doses of the parent strain and to a lesser extent the bbk32 mutant, and then disseminate to joint tissue based on signal emitted from the tibiotarsal region (Fig. S2). Based on the images obtained, the luminescence reaches its peak at day 7, consistent with a prior report (Antonara et al., 2010), most likely due to the inadequacy of the early adaptive immune response. After the adaptive immune response is activated, the emitted signal is somewhat reduced by day 10, but not eliminated. By two weeks post-infection, the emitted signal increases slightly again and continues to spread throughout the skin on the ventral surface of each mouse (Fig. 3 and 4).

BBK32 plays a role in optimal colonization and dissemination

Previous studies demonstrated that bbk32 mutants exhibit a significant but understated phenotype in overall infectivity (Seshu et al., 2006). Specifically, the ID50 of the bbk32 knockout strain was increased approximately 15-fold (Seshu et al., 2006). However, these studies were limited to a single time point and based on an entirely qualitative assessment of infection (i.e., cultivation of tissue samples) that does not distinguish between lightly or heavily infected tissues. In the instance where the phenotype was tracked in a quantitative manner, a high inoculum of 105 spirochetes was used (Li et al., 2006). Recently, another report demonstrated BBK32-mediated fibronectin binding was required for attachment to the microvasculature (Norman et al., 2008), suggesting that BBK32 may be needed for escape from the bloodstream, and thus dissemination, a step that would occur early in the borrelial colonization process. To further define the role of BBK32 in borrelial pathogenesis, we infected mice with the bbk32 mutant (JS315 pBBE22luc) and tracked colonization over time using imaging relative to its infectious parent.

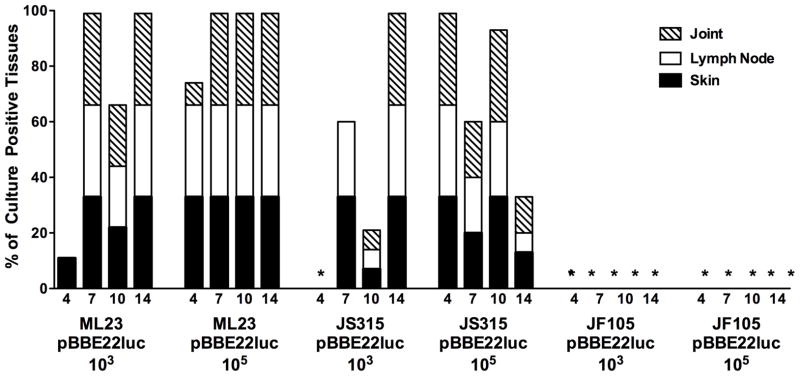

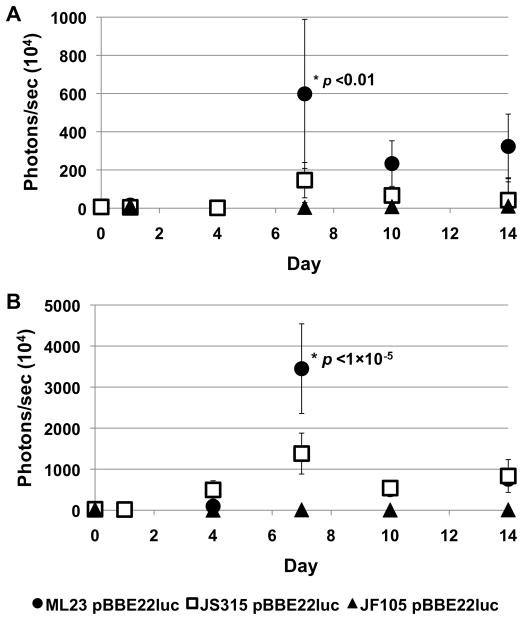

Mice infected with 103 and 105 bbk32 mutant spirochetes exhibited a decrease in colonization and a delay in dissemination when compared to the parent strain (Fig. 3 and 4). In addition, the infectivity data showed a slight decrease in colonization for the bbk32 mutant, particularly at the lower infectious dose (Fig. 5). The data obtained here for the Balb/c background indicated a decrease in sensitivity to borrelial infection relative to C3H/HeN mice of between 5- to 10-fold, which is consistent with Balb/c mice being somewhat less permissive for borrelial infection (Pahl et al., 1999; Ma et al., 1998). We used the luminescence emitted for 1 minute, to avoid saturation, from the entire mouse for each strain, dose and time point tested and the values were then averaged (Fig. 6). We reasoned that it was important to observe the luminescence from the whole mouse rather than a localized region to obtain a global assessment of disseminated borrelial infection. Although luminescence emission for both the parent strain and bbk32 mutant peak at around day 7 post-infection, the luminescence observed for the bbk32 mutant is significantly reduced at both 103 and 105 inocula with a P value of less than 0.01 and 1×10−5, respectively. The quantifiable luminescence detected by imaging indicated that, on average, the bbk32 mutant exhibited a 4.1- and 7.7-fold decrease in light emission relative to its parent 7 days post-infection (when the infection is at its peak) for mice infected with 103 and 105 spirochetes, respectively (Fig. 6). In all doses tested, the bioluminescent signal dissipated at day 10, presumably due to the increase in the host humoral response, and then increased again at day 14 (Fig. 6). Interestingly, in mice that were infected with 105 spirochetes, the total bioluminescent signal was comparable for the parent and the bbk32 mutant by day 14 (Fig. 6), consistent with the previously reported absence of a dramatic phenotype for the bbk32 mutant at higher inocula 2–3 weeks post infection (Seshu et al., 2006; Li et al., 2006). Taken together, these data suggest that optical imaging provides an additional and advantageous approach to quantify borrelial infection even under conditions where perceived subtle but significant changes are occurring during the infectious process. The absence of a clear correlation between bioluminescent signal and cultivation, whereby imaging is reduced but in vitro cultivation remains unchanged, highlights yet another benefit of in vivo imaging; specifically, that a quantitative assessment further defines the degree of infection as it progresses. In this regard, imaging allowed determination of a phenotype for the bbk32 mutant that could not otherwise be evaluated in living animals.

Figure 5. Qualitative kinetics of B. burgdorferi dissemination in Balb/c mice.

Upon completion of optical imaging for tissues from Balb/c mice infected with either 103 or 105 ML23 pBBE22luc, JS315 pBBE22luc or JF105 pBBE22luc, the animals were sacrificed and the skin, inguinal lymph node and tibiotarsal joint were harvested on day 4, 7, 10 and 14 for in vitro cultivation and outgrowth of B. burgdorferi. The x-axis indicates the strains, doses and time points tested (in days). The y-axis displays the total percentage of culture positive tissues for a given time point comprised of the three tissues tested for three to five mice depending upon the strain. The asterisks indicate that all cultures were negative for those samples.

Figure 6. Quantitation of temporal and spatial in vivo B. burgdorferi luminescence.

Balb/c mice were infected with ML23 pBBE22luc, JS315 pBBE22luc or JF105 pBBE22luc at a dose of 103 (A) or 105 (B). Three to five mice were infected with B. burgdorferi depending on the strain being tested. Mice were treated with D-luciferin 1 h and 1, 4, 7, 10 and 14 days after intradermal infection and 1 min exposure images were obtained for quantification of photons/sec. The entire body of the mouse was measured for photons/sec for all time points. Luminescence measurements were normalized by subtracting background values obtained from an infected mouse not treated with D-luciferin and imaged alongside D-luciferin treated infected mice. Luminescence values were averaged and the bars represent standard error. P values indicate the comparison between ML23 pBBE22luc and JS315 pBBE22luc at day 7 post infection.

Temporal and spatial kinetic analysis of quantified B. burgdorferi

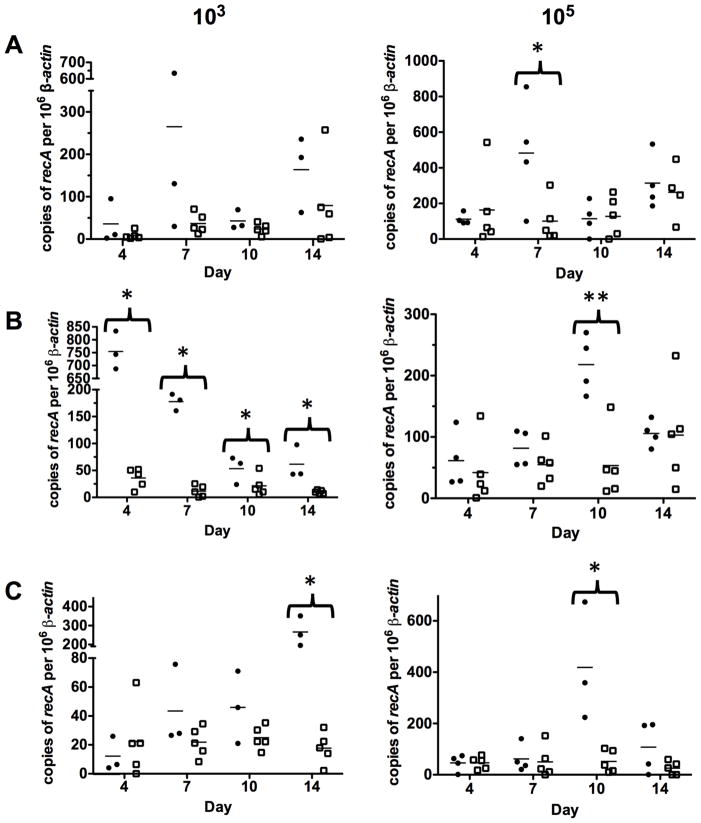

To determine how the in vivo imaging correlated with B. burgdorferi load, we analyzed tissues from mice infected with either 103 or 105 of the parent and the bbk32 mutant over time from the skin, inguinal lymph node and tibiotarsal joint using real time quantitative PCR (qPCR) and optical imaging. The results indicated that the absolute numbers of spirochetes were reduced in the bbk32 mutant to levels that in some instances were significantly different from the parent strain (Fig. 7). Surprisingly, the tissue that had the least difference between the parent and bbk32 mutant was the skin whereby neither dose exhibited a large difference with the exception of the 7 day time point from mice infected with 105 spirochetes (P value < 0.05; Fig. 7A). The average number of genomic equivalents for the parent and bbk32 mutant at 14 days post infection were similar, particularly for skin tissue obtained from mice infected with 105 spirochetes (Fig. 7A). These data are reminiscent of prior studies with bbk32 knockout strains whereby infectivity was indistinguishable at higher doses based on both qualitative and quantitative metrics of infection 2–3 weeks post-infection (Seshu et al., 2006; Li et al., 2006). In contrast to the skin, both the lymph node and joint tissue showed a significant decrease in load for the bbk32 mutant independent of dose and, in the case of the joint tissue, the parent increased over time unlike the bbk32 mutant (Fig. 7B and 7C). Joints infected with 103 B. burgdorferi were significantly different at day 14 (P value = 0.017) (Fig. 7C). Furthermore, the borrelial numbers for the bbk32 mutant were approximately 20-fold lower at days 4 and 7 in the lymph node tissue relative to the infectious parent and remained significantly lower even at later time points (P value <0.05 for all days) (Fig. 7B). These observations suggest that BBK32 is required for optimal dissemination from the site of infection and/or secondary colonization following dissemination.

Figure 7. Quantitation of borrelial genomic equivalents from Balb/c tissues over time.

Balb/c mice infected with ML23 pBBE22luc (black circles) or JS315 pBBE22luc (hollow squares) at doses of 103 or 105 (left and right columns, respectively) were sacrificed and skin (A), inguinal lymph node (B) and tibiotarsal joint (C) samples were harvested for qPCR analysis to determine the number of borrelial genomes (recA) per 106 copies of mouse beta-actin. Bar represents the mean of the samples analyzed by qPCR. *indicates a P value of <0.05 and **represents P value of <0.01.

Correlation of imaging data with quantitative PCR (qPCR)

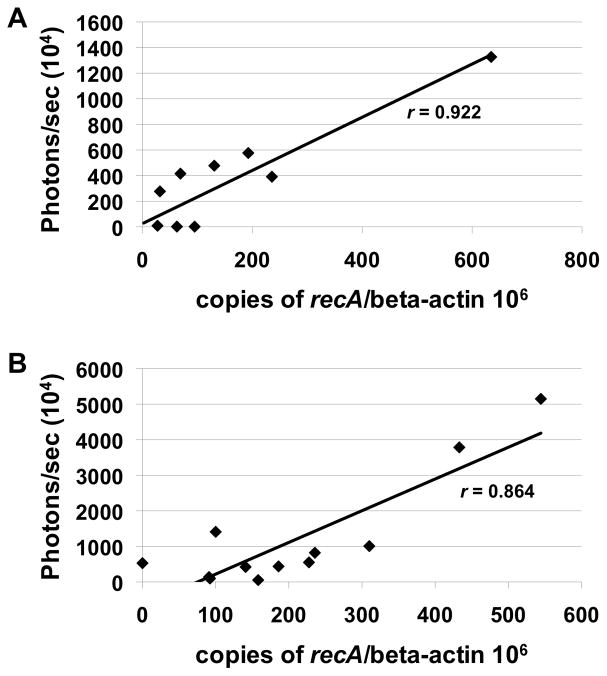

To establish whether IVIS could serve as a valid method to quantify B. burgdorferi load we calculated the correlation between the bioluminescent signal and borrelial genomic equivalents detected by qPCR. The composite values obtained for each inoculum dose tested over time were plotted. The values shown represent the individual data point used to generate the quantified imaging data (Fig. 6) graphed against the qPCR data (Fig. 7). The results obtained demonstrate that there is a strong correlation between bioluminescence and qPCR for all inocula. The calculated r values for mice infected with 103 or 105 spirochetes are 0.922 and 0.860, respectively (Fig. 8A and 8B). Taken together, the high degree of correlation indicates that optical imaging represents an adequate means to quantify borrelial numbers in experimental animal model systems.

Figure 8. Correlation of luminescence and qPCR detection of B. burgdorferi.

The skin samples of from mice infected with ML23 pBBE22luc at doses of 103 (A) and 105 (B) were evaluated for their luminescence values [p/s] relative to the genomic equivalents detected. For the 103 and 105 samples r values of 0.922 and 0.864 were obtained, respectively.

Discussion

The spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi infects and colonizes numerous tissues following dissemination. The basis for what we know regarding borrelial colonization and dissemination stems mostly from our ability to detect spirochetes by either qualitative in vitro cultivation or quantitative enumeration via quantitative PCR analyses following experimental infection. While invaluable, the aforementioned approaches require that the experimentally infected animal be sacrificed to access the desired organs and tissues in order to detect B. burgdorferi and evaluate the pathology associated with infection. As such most of what we currently understand following experimental infection is limited to end point analyses. Furthermore, with the exception of studies that utilized immunocompromised hosts (Labandeira-Rey et al., 2003; Schaible et al., 1989; Fikrig et al., 2000; Crother et al., 2003), the ability to detect B. burgdorferi within infected mammalian tissues is limited, presumably due to their paucity within infected sites and/or poor sensitivity.

With the development of several in vivo imaging modalities, it is now possible to visualize various types of biologic targets based on the specific detection technique being used (Contag et al., 1995). Recently, Norman et al. reported that fluorescent B. burgdorferi could be detected by intravital confocal microscopy in the microvasculature of infected mice (Norman et al., 2008); however, these studies required large intravenous inocula for detection and were limited in view to a finite field. In this study we utilized optical imaging to track luciferase (luc)-expressing B. burgdorferi both temporally and spatially in experimentally infected Balb/c mice. These results indicated that optical imaging represents a viable new technology to evaluate luc-expressing B. burgdorferi dissemination within infected mice over time. Specifically, bioluminescence imaging demonstrated that B. burgdorferi was readily detected immediately following intradermal inoculation and could be followed during either clearance and/or rapid dissemination, resulting in a severely reduced signal 24 hours post infection (Fig. 4). However, despite the disappearance of B. burgdorferi from the site of inoculation, at least some spirochetes recover and repopulate the infection site by 4 or 7 days post-infection dependent on the inoculum level (Fig. 3 and 4). The initial depletion of B. burgdorferi at the site of inoculation is presumably due to a robust infiltrate of innate immune cells, consistent with numerous studies indicating the susceptibility of B. burgdorferi to processing via macrophages, granulocytes, and dendritic cells (reviewed recently in Weis and Bockenstedt, 2010). Given that these same innate immune cells should be present at the inoculation site at later time points, it is curious how B. burgdorferi evades host clearance and continues to replicate. Along these lines, it is clear that over time the spirochetes spread from a localized infection and disseminate throughout the skin (Fig. 3 and 4), but the overall luminescence decreases and reaches a plateau, consistent with the notion that an untreated, immunocompetent host is not able to clear borrelial infection but is able to control it to a manageable level once adaptive immunity, particularly a humoral based response, is initiated (Barthold et al., 1991; Wang et al., 2005). This is due, in part, to the ability of B. burgdorferi to undergo antigenic variation, evade complement dependent killing, and other as yet unknown pathogenic traits that promote survival (Akins et al., 1998; McDowell et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 1997; Zhang and Norris, 1998; Eicken et al., 2002; Alitalo et al., 2002; Brooks et al., 2005; Hartmann et al., 2006; Kraiczy et al., 2004; McDowell et al., 2003). As expected, there is some variability between the infected mice within the overall distribution of the spirochetes but, nevertheless, the overall dissemination trend appeared comparable from mouse to mouse when a given strain was analyzed (Fig. 3 and 4). The only notable exception is when, at the 103 dose, some mice have obvious detectable infection based on imaging whereas other mice have very low levels of luminescence. These observations were subsequently verified by differences in spirochete enumeration as determined by quantitative real time PCR (Fig. 7) and corroborated by the correlation of luminescence and qPCR data for the parent strain (Fig. 8). This variation in dissemination is particularly evident in mice infected with the bbk32 mutant at the 103 inoculum dose at day 7 and day 10 (Fig. 3). Prior reports indicate that Balb/c mice exhibit an approximate 5- to 10-fold increase in ID50 (Pahl et al., 1999; Ma et al., 1998), which is consistent with the decreased colonization observed in this study following infection with 103 B. burgdorferi (i.e., near the apparent ID50 for Balb/c). Nevertheless, the optical imaging provides a better and more sensitive reference when compared with the qualitative infectivity assessment (Fig 5).

Based on optical imaging 1 h post infection and the temporal characteristics of the parent strain, it appears that the threshold of detection for optical imaging is in the range of approximately 102 to 103 organisms within an approximate 200 mm2 region of ventral (abdomen) skin (Fig. 2 and Fig S1). Photons are detected in all infected mice above levels seen for uninfected mice and those that are infected but not given substrate, indicating that detection is even more sensitive than what is visualized in the scale shown in Fig’s 3 and 4. However, luminescence can be more readily localized to infected sites in images when values approach the linear range (as seen in Fig 1A and Fig 2A). The subsequent loss of bioluminescence 24 h post inoculation, followed by the robust recovery observed at day 4, indicates that infectious B. burgdorferi are able to withstand the initial clearance and remaining spirochetes are capable of replication, followed by lateral dissemination through the skin. At later time points, luminescence is observed and, in most cases, concentrated within the tibiotarsal joint region, as well as within the tail (Fig. S2 and data not shown), showing the dissemination of B. burgdorferi to joint tissue. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that a portion of the signal also emanates from the skin, yielding a composite luminescent image. It is important to note that this study is limited to evaluating the infectivity of B. burgdorferi in the skin and structures that are near the surface, i.e., joint and tissue. Although it is likely that in vivo imaging will be useful in detecting B. burgdorferi from secondary colonization sites, i.e., heart tissue, the strong signal in the skin precludes this type of determination in live mice since it most likely eclipses light emission from deeper tissues, particularly if the signal from the organ is less robust.

Perhaps the most intriguing outcome of these imaging studies was the phenotype of the bbk32 mutant. Binding assays and gel overlay analyses conducted in vitro clearly indicate that the BBK32 protein from B. burgdorferi binds mammalian fibronectin (Seshu et al., 2006; Probert and Johnson, 1998; Probert et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2004; Fischer et al., 2006), and inactivation or deletion of bbk32 impairs optimal infectivity in B. burgdorferi (Seshu et al., 2006). Strikingly, the phenotype of the bbk32 mutant was most apparent following infection at low inocula; at higher inocula differences in infectivity were not readily observed. These observations suggested that B. burgdorferi contains additional proteins that can mediate fibronectin binding. Recently Brissette et al. identified additional fibronectin binding proteins in B. burgdorferi that may augment the fibronectin binding associated with BBK32 (Brissette et al., 2009). An alternative explanation is that BBK32 functions temporally at a point that was not evaluated in previous analyses. Support for this contention comes from prior studies indicating that bbk32 was highly induced under conditions that mimic the mammalian environment and tick feeding—i.e., induced 1000-fold during tick feeding and transmission to mice relative to flat ticks (Li et al., 2006)—suggesting that BBK32 production is important for transmission of B. burgdorferi into infected mammals and colonization following deposition into the site of infection. Furthermore, earlier studies demonstrated that antibodies to BBK32 reduced tick transmission of B. burgdorferi (Fikrig et al., 2000). In addition, a recent report indicated that BBK32 was required for transient binding to the microvasculature when visualized by intravital confocal microscopy (Norman et al., 2008). These observations, coupled with the mild phenotype observed for the bbk32 mutant (Li et al., 2006; Seshu et al., 2006), prompted us to re-evaluate the role of BBK32 using optical imaging. The lower signal with the bbk32 mutant (independent of the inoculum dose) suggests that BBK32 is required for optimal infectivity as the infectious process is progressing from colonization to the dissemination phase. The observation that infectivity is rescued at later time points is curious and consistent with earlier observations that bbk32 mutants were recovered 21 days post infection at inocula of 105 (Seshu et al., 2006; Li et al., 2006).

It is important to emphasize that most of the prior data was restricted to qualitative assessments of infection (i.e., cultivation of infected organs (Seshu et al., 2006; Li et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2010)) whereas quantitative data was limited to high inocula (i.e., 105) (Li et al., 2006). The results obtained herein corroborate the lack of a phenotype following a 14-day infection, at high inocula and accentuate a difference at lower inocula in mice infected with the bbk32 mutant at earlier time points (Fig’s 3, 4, and 6). It is important to emphasize that our qPCR data is predicated on a small portion of the infected mouse. Clearly, since the qPCR data is based on a subset of the total infection per mouse analyzed, the values shown in Fig. 7 represent only a correlative value and do not reflect the entire B. burgdorferi content as is seen by optical imaging. Nevertheless, these data serve as a valuable starting point in determining bacterial load of B. burgdorferi as it actively disseminates inside a living host. The sensitivity of this experimental approach suggests that optical imaging can be used to decipher subtle differences in borrelial mutants relative to their infectious parent or alternate strains in a non-invasive manner in the same set of animals over time, thereby reducing the numbers of animals required for experimental infection analyses.

The observation that luminescence from the bbk32 mutant was low early in the infection (through day 10; Fig’s 3, 4, and 6), but recovered to near wild type levels by day 14 (Fig’s 3, 4, and 6), suggests that BBK32 is required for resistance to clearance mechanisms, particularly those involving the innate immune system. Recently, Prabhakaran et al. demonstrated that in vitro BBK32 promotes the formation of superfibronectin, a similar but distinct form of fibronectin that has unique functions (Prabhakaran et al., 2009). Specifically, superfibronectin inhibits endothelial cell proliferation (Yi and Ruoslahti, 2001; Morla et al., 1994; Ambesi et al., 2005; Pasqualini et al., 1996; Prabhakaran et al., 2009) and may quell the localized immune response. As such, one function of BBK32 may be to suppress the localized innate immune response such that the infection can proceed. Further studies are required to better evaluate this hypothesis.

In summary, this study indicates that B. burgdorferi can be tracked during an active infection directly in live animals. This approach is particularly advantageous for the comparison of isogenic strains that differ in a single genetic locus. This type of analysis should allow for the functional definition for nearly any gene or gene product; specifically their role in colonization and dissemination. Given that many borrelial mutants analyzed have little or no apparent phenotype when evaluated by qualitative measures of infection, this type of strategy, which allows global whole body analyses, should provide insight into the role these proteins play, if any, in discrete steps of borrelial pathogenesis. Also, the ability to follow the infection over time provides an additional technology to assess the role of a putative virulence determinant, as was done here for BBK32, and speaks to the importance of evaluating mutants over a temporal continuum to better understand specific factors in the context of Lyme borreliosis.

Experimental Procedures

Bacterial strains and plasmids

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. E. coli strains were grown in Luria broth (LB) media under aerobic conditions at 37°C. Concentrations of antibiotics used in E. coli for selective pressure are as follows: kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; spectinomycin, 50 μg/ml. B. burgdorferi strains were grown in BSK-II media supplemented with 6% normal rabbit serum (Pel-Freez Biologicals, Rogers, AR) under conventional microaerobic conditions (1% CO2, 32°C) (Zuckert, 2007; Hyde et al., 2011). Borrelial strains were grown under antibiotic selective pressure, dependent on genetic composition, with kanamycin at 300 μg/ml, streptomycin at 50 μg/ml, or gentamicin at 50μg/ml.

Table 1.

Strains and Plasmids used in this study

| B. burgdorferi strains used in this study: | ||

| Strain | Genotype/Reference | |

| ML23 | Clonal isolate of strain B31 lacking lp25 (Labandeira-Rey and Skare, 2001) | |

| ML23 pBBE22luc | Clonal isolate of strain B31 lacking lp25 containing bbe22 and B. burgdorferi codon optimized luc gene under the control of a strong borrelial promoter (PflaB-luc) (this study) | |

| JS315 | ML23 bbk32::StrR (Seshu et al., 2006) | |

| JS315 pBBE22luc | ML23 bbk32::StrR, containing bbe22 and the B. burgdorferi codon optimized luc gene under the control of a strong borrelial promoter (PflaB-luc) (this study) | |

| JF105 | ML23 ΔdbpBA::GentR (Weening et al., 2008) | |

| JF105 pBBE22luc | ML23 ΔdbpBA::GentR, containing bbe22 and the B. burgdorferi codon optimized luc gene under the control of a strong borrelial promoter (PflaB-luc) (this study) | |

| E. coli strains used in this study: | ||

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

| Mach-1™-T1R | Φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 hsdR (rk−,mk+) DrecA1398 endA1 tonA |

Invitrogen |

| Plasmids used in this study: | ||

| Plasmid | Resistance | Comments/Source/Reference |

| pBBE22-gate | kanR | Borrelial shuttle vector pBSV2 containing pncA fragment to restore infectivity in ML23 and Gateway destination vector attR1 and attR2 sites from Invitrogen’s pDEST17 (Weening et al., 2008) |

| pJSB175 | strepR | pJD7 shuttle vector carrying PflaB-Bbluc (Blevins et al., 2007) |

| pCR8/GW/TOPO | specR | Invitrogen Gateway™ PCR cloning/entry vector |

| pBBE22luc | kanR | pBBE22-gate with PflaB-Bbluc cloned into the gateway att site by LR clonase recombination (this study) |

Genetic modifications of B. burgdorferi

A 1990 bp fragment encoding a codon optimized luciferase under the control of a constitutively expressed flagellar promoter (PflaB-luc) was PCR amplified with primers FlaB-luciferaseF (5′-GGGGATCCTCTAGAGTCGACC-3 ′ ) and F l a B-luciferaseR (CAACTTACTGCCAGGCACTTC) from pJSB175 (Blevins et al., 2007) then cloned into pCR8/GW/TOPO (Invitrogen). The PflaB-luciferase fragment was cloned into pBBE22-gate using the previously described modified recombination-based cloning system (Weening et al., 2008) resulting in pBBE22luc. B. burgdorferi strains ML23, JS315 and JF105 (Labandeira-Rey and Skare, 2001; Seshu et al., 2006; Weening et al., 2008) were made competent and transformed with pBBE22luc as described previously (Seshu et al., 2006; Weening et al., 2008; Samuels, 1995; Hyde et al., 2011). Transformants were selected for resistance to kanamycin and all putative isolates were screened for plasmid content and the ability to emit light when incubated with D-luciferin in vitro.

Western immunoblot analysis

Borrelial cells were pelleted and resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a PVDF membrane for Western analysis as previously described (Weening et al., 2008; Seshu et al., 2004; Hyde et al., 2007). Protein production was assessed using mouse monoclonal antisera to B. burgdorferi flagellum (Affinity BioReagents, Golden, CO) and goat polyclonal antisera to Firefly luciferase (AbCam Inc., Cambridge, MA) followed by incubation with rabbit anti-mouse IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and rabbit anti-goat HRP, respectively. The membrane bound immune complexes were visualized using the Western Lightning Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus detection system (Perkin Elmer).

In vitro bioluminescence assays

B. burgdorferi was grown to mid-log phase and concentrated to 108 cells/ml for ML23 pBBE22luc, JS315 pBBE22luc and JF105 pBBE22luc. Cells were serially diluted from 108 to 100 cells/ml and 100 μl of appropriate dilutions were transferred to a white flat-bottom microtiter 96 well plate. Luminescence was measured using 2104 EnVision Multilabel Reader (Perkin Elmer, Inc., Waltham, MA). Each sample for each strain was treated with a final concentration of 667 μM D-luciferin (Research Products International Corp., Mt. Prospect, IL) in PBS and immediately measured for luminescence (Kong et al., 2011). Each cell concentration for all the strains was measured for luminescence in triplicate, values were averaged, and the standard error was calculated.

Bioluminescence infectivity studies and luminescence quantitation

Six to eight week old female Balb/c mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, Maine) were used in all infectivity experiments. Mice were infected with 103 or 105 ML23 pBBE22luc, JS315 pBBE22luc or JF105 pBBE22luc by intradermal injection. To detect luciferase activity, mice were intraperitoneally injected with 5 mg D-luciferin dissolved in 100 μl PBS 10 minutes prior to imaging with an IVIS Spectrum live animal imaging system (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA) (Kong et al., 2011; Chang et al., 2011) with the exception of one mouse that was infected with B. burgdorferi but did not receive D-luciferin to serve as a negative control for background luminescence. Mice were randomly selected and imaging was performed 1 h and 1, 4, 7, 10 and 14 days after infection with the above-mentioned borrelial strains using the methods described in Kong et al (Kong et al., 2011). Luminescence was measured using 1 and 10 min exposures to obtain images for quantification and visual representation, respectively. Images were analyzed using Living Image Software from Caliper Life Sciences. ML23 pBBE22luc 103 and 105 have an n of 3 and 4, respectively. A mouse infected with 105 ML23 pBBE22luc, but given no substrate, served as a negative control for mice infected with 103 ML23 pBBE22luc. The experimental groups for JS315 pBBE22luc and JF105 pBBE22luc consisted of 5 mice per dose including the negative control mouse. Regions of interest (ROI) tool were selected to measure the luminescence in photons/second [p/s] from the 1 min exposure images using an equal area of the whole body for all mice in all experiments. The shorter exposure time was needed for quantitation to avoid saturation that occurred in some of the longer exposures. The luminescence [p/s] for mice that received D-luciferin were averaged and normalized by subtracting the background [p/s] luminescence. All images from the 10 min exposures were treated equally when corrected for background and depicted on the same photons/sec scale. Immediately after imaging mice were sacrificed on days 4, 7, 10 and 14 to harvest skin, inguinal lymph node and tibiotarsal joint samples for in vitro cultivation and qPCR analysis of B. burgdorferi genomic equivalents. For cultivation, infectivity was scored by determining the number of mice infected for a given time point and tissue and represented as a total number of culture positive samples per tissue tested. Since only three tissues were tested, e.g., the joint, lymph node, or skin, the maximal percentage of that each infected tissue could contribute to the whole would be 33.3%. An infectivity score of 100% in Fig. 5 indicates that every tissue for each mouse tested at a given dose was culture positive.

In addition to mice infected with 103 and 105 B. burgdorferi, 5 mice were infected with ML23 pBBE22luc at 101, 102 or 104 for temporal evaluation to determine a threshold of in vivo luminescence detection for B. burgdorferi and analyzed as described above. Balb/c mice were inoculated with ML23 pBBE22luc at 103, 104, 105 and 106 and 1 h post-infection quantitatively imaged for luminescence and inoculation site skin samples were taken for qPCR. Luminescence was normalized relative to an uninfected mouse treated with D-luciferin.

All animal experiments were performed in accordance to the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) guidelines. Approval for animal procedures was given by Texas A&M University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

DNA extraction of B. burgdorferi from infected tissues and quantitative PCR analysis

DNA was extracted from skin, inguinal lymph node and tibiotarsal joint samples using Roche High Pure PCR template preparation kit as previously described (Weening et al., 2008). B. burgdorferi genomic equivalents were enumerated using an Applied Biosystems ABI 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems Corp., Foster City, CA) as outlined (Weening et al., 2008). Mouse β-actin copies were detected using primers Bactin_F (5′-ACG CAG AGG GAA ATC GTG CGT GAC-3′) and Bactin_R1 (5′-ACG CGG GAG GAA GAG GAT GCG GCA GTG-3′) (Pal et al., 2008; Weening et al., 2008). Borrelial genomic equivalents were evaluated using primers, nTM17FrecA (5′-GTG GAT CTA TTG TAT TAG ATG AGG CTC TCG-3′) and nTM17RrecA (5′-GCC AAA GTT CTG CAA CAT TAA CAC CTA AAG-3′), to B. burgdorferi recA as previously described (Liveris et al., 2002). The numbers of β-actin copies were calculated by establishing a Ct standard curve of known amount β-actin gene for comparison to the Ct values of the experimental samples. All samples were measured in triplicate and values are displayed as copies of B. burgdorferi recA per 106 mouse β-actin copies.

Statistical analyses

Two factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate the significance of the main effects and interactions among variables. Following ANOVA, pre-planned differences between means on a given day or across the span of days were tested for significance using orthogonal (single degree of freedom) contrasts. Mann-Whitney one-tail test compared medians of two groups. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant for all statistical analyses.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Detection level of B. burgdorferi in vivo luminescence. Balb/c mice were infected with 101 to 105 ML23 pBBE22luc by intradermal injection. Luminescence was quantitated at 1 h and 1, 4, 7, 10 and 14 day from 1 min exposure images. The entire body of the mouse was measured for photons/sec for all time points tested. Luminescence measurements were normalized by subtracting the background measurement from an infected mouse not treated with D-luciferin and imaged alongside D-luciferin treated infected mice. Luminescence values were averaged and bars on the graph represent standard error. ML23 pBBE22luc 105 is significantly different from all doses on day 7 with a p value ranging from <1×10−15 to <1×10−7 for 101 to 104, respectively. ML23 pBBE22luc 104 is significantly different from all doses on day 7 with p values ranging from <1×10−7 to <0.05. The luminescence threshold of detection is between 102 and 103 ML23 pBBE22luc.

Figure S2. B. burgdorferi temporal and spatial dissemination to the tibiotarsal joint. Balb/c mice were infected with 105 ML23 pBBE22luc or JS315 pBBE22luc. Each image consisted of one control mouse (left) that was infected but not treated with D-luciferin and three to four infected mice treated with D-luciferin 7, 10 and 14 days post infection. A 10 min exposure image was used to obtained maximal amount of visual luminescence. All images have been normalized to the same photons/sec range of 1.82×103 to 4.8×105 (same as Fig. 3 and 4) and displayed on the color spectrum scale (right).

Acknowledgments

We thank Mike Norgard and Jon Blevins for providing plasmid pJSB175. We gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of Bonnie Seaberg, Cindy Ortiz, and Jessica Purkey. This work was supported by Public Health Service grants R01-AI058086 (to J.T.S and M.H), R01-AI047866 (to J.D.C), and Grant 48523 from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (to J.D.C).

References

- Akins DR, Bourell KW, Caimano MJ, Norgard MV, Radolf JD. A new animal model for studying Lyme disease spirochetes in a mammalian host-adapted state. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2240–2250. doi: 10.1172/JCI2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alitalo A, Meri T, Lankinen H, Seppala I, Lahdenne P, Hefty PS, Akins D, Meri S. Complement inhibitor factor H binding to Lyme disease spirochetes is mediated by inducible expression of multiple plasmid-encoded outer surface protein E paralogs. J Immunol. 2002;169:3847–3853. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambesi A, Klein RM, Pumiglia KM, McKeown-Longo PJ. Anastellin, a fragment of the first type III repeat of fibronectin, inhibits extracellular signal-regulated kinase and causes G(1) arrest in human microvessel endothelial cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:148–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonara S, Ristow L, McCarthy J, Coburn J. Effect of Borrelia burgdorferi OspC at the site of inoculation in mouse skin. Infect Immun. 2010;78:4723–4733. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00464-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthold SW, Cadavid D, Philipp MT. Animal Models of Borreliosis. In: Samuels DS, Radolf JD, editors. Borrelia: Molecular Biology, Host Interaction and Pathogenesis. Norfolk, UK: Caister Academic Press; 2010. pp. 359–412. [Google Scholar]

- Barthold SW, Persing DH, Armstrong AL, Peeples RA. Kinetics of Borrelia burgdorferi dissemination and evolution of disease after intradermal inoculation of mice. Am J Pathol. 1991;139:263–273. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins JS, Hagman KE, Norgard MV. Assessment of decorin-binding protein A to the infectivity of Borrelia burgdorferi in the murine models of needle and tick infection. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:82. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins JS, Revel AT, Smith AH, Bachlani GN, Norgard MV. Adaptation of a luciferase gene reporter and lac expression system to Borrelia burgdorferi. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:1501–1513. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02454-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brissette CA, Bykowski T, Cooley AE, Bowman A, Stevenson B. Borrelia burgdorferi RevA antigen binds host fibronectin. Infect Immun. 2009;77:2802–2812. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00227-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks CS, Vuppala SR, Jett AM, Alitalo A, Meri S, Akins DR. Complement regulator-acquiring surface protein 1 imparts resistance to human serum in Borrelia burgdorferi. J Immunol. 2005;175:3299–3308. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns SM, Joh D, Francis KP, Shortliffe LD, Gruber CA, Contag PR, Contag CH. Revealing the spatiotemporal patterns of bacterial infectious diseases using bioluminescent pathogens and whole body imaging. Contrib Microbiol. 2001;9:71–88. doi: 10.1159/000060392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang MH, Cirillo SLG, Cirillo JD. Using luciferase to image bacterial infections in mice. J Vis Exp. 2011:2547. doi: 10.3791/2547. pii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contag CH, Contag PR, Mullins JI, Spilman SD, Stevenson DK, Benaron DA. Photonic detection of bacterial pathogens in living hosts. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:593–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18040593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crother TR, Champion CI, Wu XY, Blanco DR, Miller JN, Lovett MA. Antigenic composition of Borrelia burgdorferi during infection of SCID mice. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3419–3428. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3419-3428.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edinger M, Cao YA, Hornig YS, Jenkins DE, Verneris MR, Bachmann MH, Negrin RS, Contag CH. Advancing animal models of neoplasia through in vivo bioluminescence imaging. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:2128–2136. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00410-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eicken C, Sharma V, Klabunde T, Lawrenz MB, Hardham JM, Norris SJ, Sacchettini JC. Crystal structure of Lyme disease variable surface antigen VlsE of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21691–21696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201547200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fikrig E, Feng W, Barthold SW, Telford SR, 3rd, Flavell RA. Arthropod- and host-specific Borrelia burgdorferi bbk32 expression and the inhibition of spirochete transmission. J Immunol. 2000;164:5344–5351. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.5344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer JR, LeBlanc KT, Leong JM. Fibronectin binding protein BBK32 of the Lyme disease spirochete promotes bacterial attachment to glycosaminoglycans. Infect Immun. 2006;74:435–441. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.435-441.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis KP, Joh D, Bellinger-Kawahara C, Hawkinson MJ, Purchio TF, Contag PR. Monitoring bioluminescent Staphylococcus aureus infections in living mice using a novel luxABCDE construct. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3594–3600. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3594-3600.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis KP, Yu J, Bellinger-Kawahara C, Joh D, Hawkinson MJ, Xiao G, Purchio TF, Caparon MG, Lipsitch M, Contag PR. Visualizing pneumococcal infections in the lungs of live mice using bioluminescent Streptococcus pneumoniae transformed with a novel Gram-positive lux transposon. Infect Immun. 2001;69:3350–3358. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.3350-3358.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann K, Corvey C, Skerka C, Kirschfink M, Karas M, Brade V, Miller JC, Stevenson B, Wallich R, Zipfel PF, et al. Functional characterization of BbCRASP-2, a distinct outer membrane protein of Borrelia burgdorferi that binds host complement regulators factor H and FHL-1. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61:1220–1236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde JA, Trzeciakowski JP, Skare JT. Borrelia burgdorferi alters its gene expression and antigenic profile in response to CO2 levels. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:437–445. doi: 10.1128/JB.01109-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde JA, Weening EH, Skare JT. Genetic transformation of Borrelia burgdorferi. Curr Protoc Microbiol. 2011;Chapter 12(Unit 12C.4) doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc12c04s20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Singvall J, Schwarz-Linek U, Johnson BJ, Potts JR, Höök M. BBK32, a fibronectin binding MSCRAMM from Borrelia burgdorferi, contains a disordered region that undergoes a conformational change on ligand binding. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41706–41714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401691200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Y, Shi Y, Chang M, Akin AR, Francis KP, Zhang N, Troy TL, Yao H, Rao J, Cirillo SLG, et al. Whole-body imaging of infection using bioluminescence. Curr Protoc Microbiol. 2011;Chapter 2(Unit2C.4) doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc02c04s21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraiczy P, Hartmann K, Hellwage J, Skerka C, Kirschfink M, Brade V, Zipfel PF, Wallich R, Stevenson B. Immunological characterization of the complement regulator factor H-binding CRASP and Erp proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi. Int J Med Microbiol. 2004;293(Suppl 37):152–157. doi: 10.1016/s1433-1128(04)80029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labandeira-Rey M, Seshu J, Skare JT. The absence of linear plasmid 25 or 28-1 of Borrelia burgdorferi dramatically alters the kinetics of experimental infection via distinct mechanisms. Infect Immun. 2003;71:4608–4613. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.8.4608-4613.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labandeira-Rey M, Skare JT. Decreased infectivity in Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 is associated with loss of linear plasmid 25 or 28-1. Infect Immun. 2001;69:446–455. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.446-455.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Liu X, Beck DS, Kantor FS, Fikrig E. Borrelia burgdorferi lacking BBK32, a fibronectin-binding protein, retains full pathogenicity. Infect Immun. 2006;74:3305–3313. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02035-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liveris D, Wang G, Girao G, Byrne DW, Nowakowski J, McKenna D, Nadelman R, Wormser GP, Schwartz I. Quantitative detection of Borrelia burgdorferi in 2-millimeter skin samples of erythema migrans lesions: correlation of results with clinical and laboratory findings. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:1249–1253. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.4.1249-1253.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Seiler KP, Eichwald EJ, Weis JH, Teuscher C, Weis JJ. Distinct characteristics of resistance to Borrelia burgdorferi-induced arthritis in C57BL/6N mice. Infect Immun. 1998;66:161–168. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.161-168.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell JV, Sung SY, Hu LT, Marconi RT. Evidence that the variable regions of the central domain of VlsE are antigenic during infection with Lyme disease spirochetes. Infect Immun. 2002;70:4196–4203. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4196-4203.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell JV, Wolfgang J, Tran E, Metts MS, Hamilton D, Marconi RT. Comprehensive analysis of the factor H binding capabilities of Borrelia species associated with Lyme disease: delineation of two distinct classes of factor H binding proteins. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3597–3602. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3597-3602.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty TJ, Norman MU, Colarusso P, Bankhead T, Kubes P, Chaconas G. Real-time high resolution 3D imaging of the Lyme disease spirochete adhering to and escaping from the vasculature of a living host. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000090. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morla A, Zhang Z, Ruoslahti E. Superfibronectin is a functionally distinct form of fibronectin. Nature. 1994;367:193–196. doi: 10.1038/367193a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadelman RB, Wormser GP. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet. 1998;352:557–565. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)01146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman MU, Moriarty TJ, Dresser AR, Millen B, Kubes P, Chaconas G. Molecular mechanisms involved in vascular interactions of the Lyme disease pathogen in a living host. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000169. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl A, Kühlbrandt U, Brune K, Röllinghoff M, Gessner A. Quantitative detection of Borrelia burgdorferi by real-time PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1958–1963. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1958-1963.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal U, Wang P, Bao F, Yang X, Samanta S, Schoen R, Wormser GP, Schwartz I, Fikrig E. Borrelia burgdorferi basic membrane proteins A and B participate in the genesis of Lyme arthritis. J Exp Med. 2008;205:133–141. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualini R, Bourdoulous S, Koivunen E, Woods VL, Jr, Ruoslahti E. A polymeric form of fibronectin has antimetastatic effects against multiple tumor types. Nat Med. 1996;2:1197–1203. doi: 10.1038/nm1196-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakaran S, Liang X, Skare JT, Potts JR, Höök M. A novel fibronectin binding motif in MSCRAMMs targets F3 modules. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probert WS, Kim JH, Höök M, Johnson BJ. Mapping the ligand-binding region of Borrelia burgdorferi fibronectin-binding protein BBK32. Infect Immun. 2001;69:4129–4133. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.6.4129-4133.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probert WS, Johnson BJ. Identification of a 47 kDa fibronectin-binding protein expressed by Borrelia burgdorferi isolate B31. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:1003–1015. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purser JE, Lawrenz MB, Caimano MJ, Howell JK, Radolf JD, Norris SJ. A plasmid-encoded nicotinamidase (PncA) is essential for infectivity of Borrelia burgdorferi in a mammalian host. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:753–764. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purser JE, Norris SJ. Correlation between plasmid content and infectivity in Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13865–13870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.25.13865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee KJ, Cheng H, Harris A, Morin C, Kaper JB, Hecht G. Determination of spatial and temporal colonization of enteropathogenic E. coli and enterohemorrhagic E. coli in mice using bioluminescent in vivo imaging. Gut Microbes. 2010;2:34–41. doi: 10.4161/gmic.2.1.14882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa PA, Tilly K, Stewart PE. The burgeoning molecular genetics of the Lyme disease spirochaete. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:129–143. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa PA, Cabello FC, Samuels DS. Genetic Manipulation of Borrelia burgdorferi. In: Samuels DS, Radolf JD, editors. Borrelia: Molecular Biology, Host Interaction and Pathogenesis. Norfolk, UK: Caister Academic Press; 2010. pp. 189–220. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels DS. Electrotransformation of the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Meth Mol Biol. 1995;47:253–259. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-310-4:253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaible UE, Kramer MD, Museteanu C, Zimmer G, Mossmann H, Simon MM. The severe combined immunodeficiency (scid) mouse. A laboratory model for the analysis of Lyme arthritis and carditis. J Exp Med. 1989;170:1427–1432. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.4.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seshu J, Boylan JA, Gherardini FC, Skare JT. Dissolved oxygen levels alter gene expression and antigen profiles in Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 2004;72:1580–1586. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.3.1580-1586.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seshu J, Esteve-Gassent MD, Labandeira-Rey M, Kim JH, Trzeciakowski JP, Höök M, Skare JT. Inactivation of the fibronectin-binding adhesin gene bbk32 significantly attenuates the infectivity potential of Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:1591–1601. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.05042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Xu Q, McShan K, Liang FT. Both decorin-binding proteins A and B are critical for the overall virulence of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 2008;76:1239–1246. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00897-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanek G, Strle F. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet. 2003;362:1639–1647. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14798-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steere AC, Coburn J, Glickstein L. The emergence of Lyme disease. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1093–1101. doi: 10.1172/JCI21681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Aguero-Rosenfeld ME, Wormser GP, Schwartz I. Borrelia: Molecular Biology, Host Interaction and Pathogenesis. Norfolk, UK: Caister Academic Press; 2010. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi; pp. 443–466. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Ma Y, Weis JH, Zachary JF, Kirschning CJ, Weis JJ. Relative contributions of innate and acquired host responses to bacterial control and arthritis development in Lyme disease. Infect Immun. 2005;73:657–660. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.657-660.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weening EH, Parveen N, Trzeciakowski JP, Leong JM, Höök M, Skare JT. Borrelia burgdorferi lacking DbpBA exhibits an early survival defect during experimental infection. Infect Immun. 2008;76:5694–5705. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00690-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis JJ, Bockenstedt L. Borrelia: Molecular Biology, Host Interaction and Pathogenesis. Norfolk, UK: Caister Academic Press; 2010. Host Response; pp. 413–442. [Google Scholar]

- Yi M, Ruoslahti E. A fibronectin fragment inhibits tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:620–624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JR, Hardham JM, Barbour AG, Norris SJ. Antigenic variation in Lyme disease borreliae by promiscuous recombination of VMP-like sequence cassettes. Cell. 1997;89:275–285. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80206-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JR, Norris SJ. Kinetics and in vivo induction of genetic variation of vlsE in Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3689–3697. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3689-3697.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zückert WR. Laboratory Maintenance of Borrelia burgdorferi. Curr Protoc Microbiol. 2007;Chapter 12(Unit 12C.1) doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc12c01s4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Detection level of B. burgdorferi in vivo luminescence. Balb/c mice were infected with 101 to 105 ML23 pBBE22luc by intradermal injection. Luminescence was quantitated at 1 h and 1, 4, 7, 10 and 14 day from 1 min exposure images. The entire body of the mouse was measured for photons/sec for all time points tested. Luminescence measurements were normalized by subtracting the background measurement from an infected mouse not treated with D-luciferin and imaged alongside D-luciferin treated infected mice. Luminescence values were averaged and bars on the graph represent standard error. ML23 pBBE22luc 105 is significantly different from all doses on day 7 with a p value ranging from <1×10−15 to <1×10−7 for 101 to 104, respectively. ML23 pBBE22luc 104 is significantly different from all doses on day 7 with p values ranging from <1×10−7 to <0.05. The luminescence threshold of detection is between 102 and 103 ML23 pBBE22luc.

Figure S2. B. burgdorferi temporal and spatial dissemination to the tibiotarsal joint. Balb/c mice were infected with 105 ML23 pBBE22luc or JS315 pBBE22luc. Each image consisted of one control mouse (left) that was infected but not treated with D-luciferin and three to four infected mice treated with D-luciferin 7, 10 and 14 days post infection. A 10 min exposure image was used to obtained maximal amount of visual luminescence. All images have been normalized to the same photons/sec range of 1.82×103 to 4.8×105 (same as Fig. 3 and 4) and displayed on the color spectrum scale (right).