Abstract

Background

Coronary artery calcification (CAC) is associated with increased mortality risk in the general population. Although individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are at markedly increased mortality risk, the incidence, prevalence, and prognosis of CAC in CKD is not well-understood.

Study Design

Cross-sectional observational study.

Setting and Participants

Analysis of 1,908 participants who underwent coronary calcium scanning as part of the multi-ethnic CRIC (Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort) Study.

Predictor

Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) computed using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study equation, stratified by race, sex and diabetic status. eGFR was treated as a continous variable and a categorical variable compared to the reference range of >60 ml/min/1.73 m2

Measurements

CAC detected using CT scans using either an Imatron C-300 electron beam computed tomography scanner or multi-detector CT scanner. CAC was computed using the Agatston score, as a categorical variable. Analyses were performed using ordinal logistic regression.

Results

We found a strong and graded relationship between lower eGFR and increasing CAC. In unadjusted models, ORs increased from 1.68 (95% CI, 1.23–2.31) for eGFR from 50–59 to 2.82 (95% CI, 2.06–3.85) for eGFR of <30. Multivariable adjustment only partially attenuated the results (OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.07–2.20) for eGFR<30.

Limitations

Use of eGFR rather than measured GFR.

Conclusions

We demonstrated a graded relationship between severity of CKD and CAC, independent of traditional risk factors. These findings supports recent guidelines that state that if vascular calcification is present, it should be considered as a complementary component to be included in the decision making required for individualizing treatment of CKD.

Non-contrast cardiac CT (calcium scan) is a highly sensitive, non-invasive technique in detecting coronary artery calcification (CAC) and hence is a valuable tool for population-based studies1,2. CAC detected by CT correlates strongly with atherosclerotic plaque burden and the CAC score predicts the future occurrence of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events2,3,4,5, underscoring its value as a surrogate for cardiovascular disease in epidemiologic cohorts.

Although subjects with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are at markedly increased risk for cardiovascular mortality, the incidence, prevalence, and prognosis of CAC in CKD is not well-understood. While there is a well-established and graded relationship between duration of end-stage renal disease and CAC,6,7,8 fewer data are available on the relationship of CAC and earlier stages of CKD.9,10 In healthy populations, CAC detected by CT correlates strongly with atherosclerotic plaque burden and the CAC score predicts the future occurrence of fatal/non-fatal cardiovascular events.11,12 Multiple studies using CT have found a high prevalence and severity of CAC in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD)1–3, a finding whose prognostic implications have been speculated to be similar to that in populations not on dialysis. 13,14 In this population, CAC has been correlated with traditional cardiovascular risk factors as well as with serum phosphorus levels, the serum calcium-phosphorus product, and the use of calcium-based phosphate binders1,15,16.

There are scarce data on CAC in CKD prior to onset of ESRD. Nakamura17 examined the relationship of histopathology with CAC across the full spectrum of CKD and demonstrated that progressive intimal calcification and atherosclerosis occurs with CKD. The National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) established the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study in 2001.18 The overall goals of CRIC are to study risk factors for kidney disease progression and development of CVD in CKD patients and to develop predictive models to identify high-risk subgroups.19 One component of the study protocol designed to assess the level of atherosclerosis includes CAC scans that have been performed in 1908 participants. This manuscript assesses the cross-sectional relationship of CAC across different degrees of eGFR, examining if these relationships vary across racial subgroups.

Methods

Measurements

Medical history, anthropometric measurements, and laboratory data were obtained for each participant. Questionnaires supplied information about age, gender, ethnicity, and medical history. Information on physical activity was obtained during the baseline examination using a combination of self-administered and interviewer-administered questionnaires. Physical activity comprised self-reported leisure, conditioning, occupational and household activities, and was quantitated by hours per day of activity. Current smoking was defined as having smoked a cigarette in the last 30 days. Alcohol use was defined as never, former, or current. Diabetes was defined as a fasting glucose ≥ 126 mg/dl or on hypoglycemic medication. Use of antihypertensive and other medications were based on clinic staff entry of prescribed medications.

Resting blood pressure was measured three times in the seated position using a Dinamap model Pro 100 automated oscillometric sphygmomanometer (Critikon, Tampa, Florida) and the average of the 2nd and 3rd readings was recorded. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg, or use of medication prescribed for hypertension. Body mass index was calculated from the equation weight (kg)/height (m2).

Total and HDL cholesterol were measured from blood samples obtained after a 12-hour fast. LDL cholesterol was calculated with the Friedewald equation(11). CRP was measured using the BNII nephelometer (N High Sensitivity CRP; Dade Behring Inc., Deerfield, IL) at the University of Vermont Laboratory for Clinical Biochemistry Research. Analytical intra-assay CVs ranged from 2.3 – 4.4% and inter-assay CVs ranged from 2.1–5.7%.

The presence and number of risk factors for each subject was calculated based on the National Cholesterol Education Program guidelines.20 Risk factors included: age ( >45 years for men, >55 years for women), current cigarette smoking, diabetes mellitus, history of premature coronary artery disease in first-degree relatives (< 55 years in men, < 65 years in women), hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia. Hypercholesterolemia was defined as use of cholesterol lowering medications or, in the absence of use of cholesterol lowering medications, a total serum cholesterol >200 mg/dL.

Assessment of Kidney Function

An overnight random morning urine sample and fasting venous blood were collected during the study visit temporally associated with the CAC scan. Albumin and creatinine were measured in urine and the albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR) was calculated for each study participant. A Beckman Coulter analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) was used for all biochemical measurements. Urine albumin was quantified by a turbidimetric method, and the coefficient of variation ranged from 2.6 to 4.4%. Both serum and urine creatinine concentrations were determined by the alkaline picrate method. The serum value was calibrated to values generated by the Cleveland Clinic laboratory to ensure valid inferences with respect to eGFR. The coefficient of variation for urine creatinine ranged from 2.8 to 3.7%, whereas the coefficient of variation for serum creatinine ranged from 1.5 to 5.0%.

The estimated by glomerular filtration rate was calculated using the 4-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study equation.21 Our CKD definition was based on the National Kidney Foundation’s KDOQI (Kidney Disease Outcome Quality Initiative) guidelines, which defines CKD as a glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min/1.73 m2.22 Serum creatinine was measured using the modified Jaffe method and was calibrated using a 2-step process. First, NHANES III (Third National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey) creatinine values were calibrated to the Cleveland Clinic Laboratory, requiring a correction factor of 0.23 mg/dl (20.3 _mol/L).23 Then age-specific (20 to 39, 40 to 59, 60 to 69, >70 years of age) and gender-specific creatinine values were aligned to the corresponding corrected NHANES III age- and gender specific means. We also evaluated the data based upon the CKD-EPI study equation (Tables S1–S3, available as online supplementary material).

Imaging Methods

All participants underwent two CT scans at the same time for evaluation of CAC, after signing informed consent. CT scans were obtained using either an Imatron C-300 Electron Beam computed tomography scanner or multi-detector CT scanner. Prior studies have validated that scores are highly concordant between Electron Beam and multi-detector scanners.24 Thirty to forty contiguous tomographic slices were obtained at 3 mm intervals beginning one centimeter below the carina and progressing caudally to include the entire coronary tree. Methods for CAC scanning have been previously well described.25

Calcium Scoring

All scans were analyzed with a commercially available software package (Neo Imagery Technologies, City of Industry, California). An attenuation threshold of 130 Hounsfield units and a minimum of 3 contiguous pixels were utilized for identification of a calcific lesion. Each focus exceeding the minimum criteria was scored using the algorithm developed by Agatston et al,26 calculated by multiplying the lesion area by a density factor derived from the maximal Hounsfield unit (Hu) within this area. The density factor was assigned in the following manner: 1 for lesions with peak attenuation of 130–199 Hu, 2 for lesions with peak attenuation of 200–299 Hu, 3 for lesions with peak attenuation of 300–399 Hu, and 4 for lesions with peak attenuation >400 Hu. The total CAC score was determined by summing individual lesion scores from each of four anatomical sites (left main, left anterior descending, left circumflex, and right coronary artery).1 The average of the two scores were used in the analysis.

Statistics

Variables used in this analysis included age, race (African American, non-Hispanic Caucasian, Other), sex, diabetic status, hyperlipidemia (including LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides), blood pressure (Systolic BP and Diastolic BP), current smoking status, BMI, albuminuria and GFR estimated (eGFR) using the MDRD Study equation. The baseline characteristics of CRIC participants included in the analysis was summarized using frequencies for categorical variables and mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables. For easier clinical interpretation, eGFR is categorized into five levels: <30, 30–40, 40–50, 50–60 and >60, chosen to ensure relatively even distribution of study participants across GFR categories. CAC is categorized into four levels: 0, 0–100, 100–400 and >400 units.

We first explored the associations between the categorized eGFR and CAC, followed by analyses stratified by race, sex and diabetic status separately. We then fit ordinal logistic regression models using the four-level CAC as the outcome and calculated the odds ratios (OR) of having higher level of CAC score among participants with lower level of eGFR (<30, 30–40, 40–50, 50–60 ml/min/1.73 m2) compared with participants with eGFR>60. Both unadjusted ORs and ORs adjusted for the variables listed above and clinical site were calculated together with the 95% confidence intervals. The proportional odds assumption for the ordinal logistic regression model was satisfied in the final multivariable model.

All analyses were done in SAS 9.2 and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Of a total of 2,008 CRIC participants who had a CAC scan, 61 were excluded because their first scan was more than 3 years after baseline, 13 were excluded because of missing eGFR measure at the time of the scan and 26 who were receiving chronic dialysis therapy at time of scan (n=26). Thus, a total of 1,908 CRIC baseline participants who underwent CT for CAC quantification were analyzed for this manuscript.

Table 1 demonstrates demographics and baseline characteristics of the entire cohort (n=1908), and data subdivided by eGFR category. Increasing age, African American Race, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and current smoking were all associated with lower eGFR, while gender and BMI were not.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics stratified by eGFR.

| All | eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2) | p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 | 30–<40 | 40–<50 | 50–<60 | >60 | |||

| No. | 1908 | 408 | 447 | 471 | 368 | 214 | |

| Age | 58.5 +/− 11.4 | 57.8 +/− 12.2 | 60.7 +/− 11.3 | 60.5 +/− 11.1 | 57.7 +/− 9.5 | 52.5 +/− 11.3 | <.001 |

| Women | 892 (46.8%) | 197 (48.3%) | 215 (48.1%) | 203 (43.1%) | 174 (47.3%) | 103 (48.1%) | 0.5 |

| Racethnicity | <.001 | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 645 (33.8%) | 144 (35.3%) | 127 (28.4%) | 143 (30.4%) | 132 (35.9%) | 99 (46.3%) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 829 (43.4%) | 139 (34.1%) | 185 (41.4%) | 230 (48.8%) | 182 (49.5%) | 93 (43.5%) | |

| Other | 434 (22.7%) | 125 (30.6%) | 135 (30.2%) | 98 (20.8%) | 54 (14.7%) | 22 (10.3%) | |

| Diabetes | 877 (46.0%) | 236 (57.8%) | 241 (53.9%) | 216 (45.9%) | 114 (31%) | 70 (32.7%) | <.001 |

| Current Smoking | 189 (9.91%) | 52 (12.7%) | 41 (9.2%) | 53 (11.3%) | 22 (6%) | 21 (9.8%) | 0.02 |

| Any CVD | 473 (24.8%) | 133 (32.6%) | 122 (27.3%) | 118 (25.1%) | 62 (16.8%) | 38 (17.8%) | <.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.16 +/− 6.68 | 31.45 +/− 7.23 | 31.20 +/− 6.27 | 31.14 +/− 6.63 | 31.07 +/− 6.89 | 30.74 +/− 6.23 | 0.8 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1643 (86.1%) | 370 (90.7%) | 406 (90.8%) | 413 (87.7%) | 305 (82.9%) | 149 (69.6%) | <.001 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 186.5 +/−44.0 | 184.7 +/−48.3 | 182.3 +/−43.5 | 187.2 +/−43.4 | 188.7 +/−42.1 | 193.7 +/−39.6 | 0.02 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 49.0 +/−15.8 | 46.7 +/−15.0 | 47.3 +/−15.5 | 48.5 +/−15.3 | 52.3 +/−15.9 | 52.2 +/−17.4 | <.001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 103.2 +/−34.7 | 97.8 +/−35.6 | 98.3 +/−33.2 | 105.1 +/−34.8 | 107.5 +/−34.1 | 112.1 +/−34.1 | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 1649 (86.6%) | 381 (93.4%) | 419 (93.7%) | 418 (88.7%) | 283 (77.1%) | 148 (69.8%) | <.001 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 126.4 +/−21.1 | 133.1 +/−23.4 | 127.9 +/−20.5 | 124.4 +/−20.2 | 122.5 +/−18.4 | 121.1 +/−20.2 | <.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 70.6 +/−12.4 | 71.2 +/−12.9 | 69.1 +/−12.4 | 69.9 +/−12.3 | 71.3 +/−11.8 | 72.5 +/−12.8 | 0.005 |

| Phosphate (mg/dL) | 3.69 +/−0.67 | 4.05 +/−0.79 | 3.71 +/−0.61 | 3.61 +/−0.59 | 3.48 +/−0.57 | 3.51 +/−0.55 | <.001 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.31 +/−0.53 | 9.11 +/−0.67 | 9.30 +/−0.50 | 9.36 +/−0.49 | 9.43 +/−0.42 | 9.43 +/−0.41 | <.001 |

| Total Parathyroid Hormone (pg/mL) | 68.0 +/−68.5 | 122.7 +/−114.4 | 67.1 +/−47.3 | 51.4 +/−30.4 | 44.9 +/−27.5 | 41.1 +/−27.0 | <.001 |

| Albuminuria category | <.001 | ||||||

| <30 mg/d | 787 (44.0%) | 56 (14.7%) | 147 (34.8%) | 224 (50.5%) | 220 (63%) | 140 (72.5%) | |

| 30–300 mg/d | 441 (24.7%) | 95 (24.9%) | 114 (27%) | 111 (25%) | 83 (23.8%) | 38 (19.7%) | |

| 300–1000 mg/d | 249 (13.9%) | 82 (21.5%) | 81 (19.2%) | 54 (12.2%) | 21 (6%) | 11 (5.7%) | |

| >=1000 mg/d | 312 (17.4%) | 148 (38.8%) | 80 (19%) | 55 (12.4%) | 25 (7.2%) | 4 (2.1%) | |

| Urine Albumin (g/24 h) | |||||||

| Mean | 0.70 +/− 1.66 | 1.55 +/−2.34 | 0.76 +/−1.72 | 0.52 +/−1.43 | 0.23 +/−0.76 | 0.13 +/−0.50 | |

| Median | 0.05 (0.01, 0.53) | 0.58 (0.08, 2.02) | 0.10 (0.02, 0.63) | 0.03 (0.01, 0.28) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.08) | 0.01 (0.01, 0.03) | . |

| Medication Use | . | ||||||

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 1292 (68.1%) | 282 (69.5%) | 337 (75.9%) | 347 (74%) | 228 (62.5%) | 98 (46%) | <.001 |

| Alpha blockers | 271 (14.3%) | 84 (20.7%) | 63 (14.2%) | 76 (16.2%) | 29 (7.9%) | 19 (8.9%) | <.001 |

| Beta blockers | 861 (45.4%) | 228 (56.2%) | 216 (48.6%) | 217 (46.3%) | 133 (36.4%) | 67 (31.5%) | <.001 |

| CCBs | 750 (39.5%) | 207 (51%) | 180 (40.5%) | 187 (39.9%) | 115 (31.5%) | 61 (28.6%) | <.001 |

| Diuretics | 1036 (54.6%) | 287 (70.7%) | 260 (58.6%) | 246 (52.5%) | 166 (45.5%) | 77 (36.2%) | <.001 |

| Phosphate binder | 129 (6.80%) | 57 (14%) | 22 (5%) | 17 (3.6%) | 23 (6.3%) | 10 (4.7%) | <.001 |

| Active Vitamin D use | 96 (5.06%) | 61 (15%) | 23 (5.2%) | 8 (1.7%) | 2 (0.5%) | 2 (0.9%) | <.001 |

Categorical variables are shown as number (percentage); continuous variables as mean +/− standard deviation or median (25th, 75th percentile).

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CCB, calcium channel blocker; CVD, cardiovascular disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein;.

Conversion factors for units: total, HDL, and LDL cholesterol in mg/dL to mmol/L, x0.02586; calcium in mg/dL to mmol/L, x0.2495. No conversion necessary for parathyroid hormone in pg/mL and ng/L.

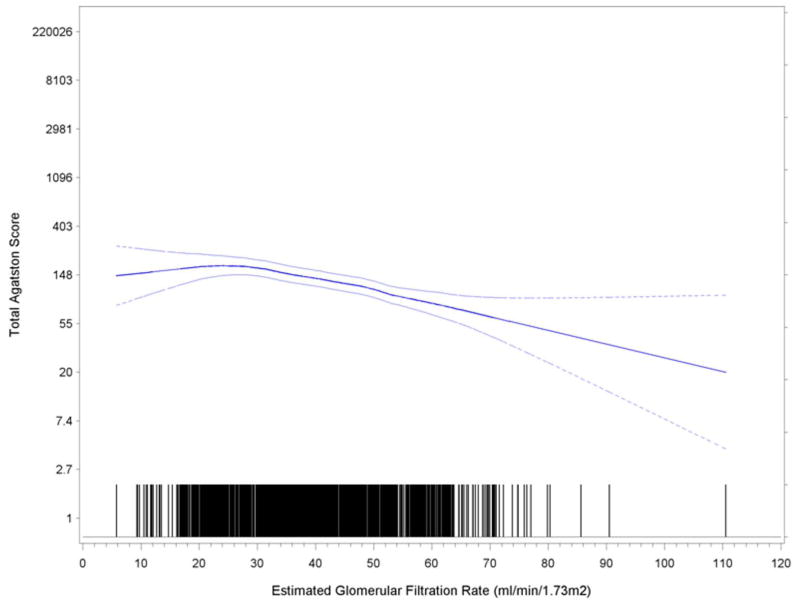

Table 2 demonstrates that mean and median CAC scores were inversely associated with eGFR category from >60 to <30 ml/min/1.73 m2 (Chi Square = 78.8, P < 0.001). There was a strong and graded relationship between lower kidney function and increasing levels of CAC. Table 2 demonstrates frequency of CAC based upon common cutpoints (0, 1–100, 101–400, >400), similarly demonstrating greater severity of CAC with lower levels of eGFR. Participants with diabetes (n=877) had significantly higher prevalence and severity of scores as compared to those without (n=1031) (p<0.001). Frequency of higher scores (CAC > 100) was markedly higher among persons with diabetes (439 of 877, 50%) compared to 270 of 1031 without diabetes (26%). Lower kdiney function was associated with increased prevalence and severity of scores (p<0.001) as shown in figure 1.

Table 2.

Bivariate associations between eGFR and CAC

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73m ) at EBT Visit | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 1908) | <30 (n = 408) | 30–<40 (n = 447) | 40–<50 (n = 471) | 50–<60 (n = 368) | >60 (n = 214) | p-value | |

| Mean CAC score* | 327.94 +/− 737.51 | 406.13 +/− 747.68 | 369.24+/− 804.44 | 356.81+/− 785.72 | 229.26+/− 591.01 | 198.75+/− 657.12 | <0.001 |

| Median CAC score | 27 | 70 | 47 | 53 | 7 | 0 | |

| CAC score category | <.001 | ||||||

| 0 | 661 (34.6%) | 128 (31.4%) | 130 (29.1%) | 146 (31%) | 143 (38.9%) | 114 (53.3%) | |

| >0–<100 | 538 (28.2%) | 100 (24.5%) | 141 (31.5%) | 124 (26.3%) | 115 (31.3%) | 58 (27.1%) | |

| >100–≤400 | 306 (16.0%) | 69 (16.9%) | 65 (14.5%) | 97 (20.6%) | 57 (15.5%) | 18 (8.4%) | |

| >400 | 403 (21.1%) | 111 (27.2%) | 111 (24.8%) | 104 (22.1%) | 53 (14.4%) | 24 (11.2%) | |

Catgorical variables shown as number (percentage).

values shown as mean +/− standard deviation.

CAC, coronary artery calcification; EBT, electron-beam tomography; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate

Figure 1.

Relationship between eGFR and CAC. Boundary lines are 95% confidence intervals.

Ethnicity was also evaluated, and among the 1908 participants, 829 were white, 646 were African-American, 433 were classified as other. Prevalence of CAC was slightly lower among African-Americans than whites. Scores of zero were present in 271/829 (33.0%) of whites and 243/646 (38%) of African Americans. Whites had a higher prevalence of CAC >100 (41%), compared to African-Americans (33%). Both whites (p<0.001) and African-Americans (p=0.002) had significant independent associations of CAC with lower levels of CKD.

Prevalence and severity of CAC was higher among men than women. In unadjusted models, lower eGFR was associated with high CAC, with odds ratios increasing from 1.68 (95% confidence interval, 1.23–2.31) for eGFR from 50–59 ml/min/1.73 m2 (as compared to >60), increasing to 2.82 (95% CI, 2.06–3.85) with eGFR of <30 ml/min/1.73 m2. These relationships were attenuated by multivariable adjustment, but remained statistically significant for eGFR<30 as compared to >60 group (OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.07–2.20).

Table 3 shows the relationship of CVD and CAC, both before and after multivariable adjustment for age, race, sex, diabetic status, current smoking status, prior CVD, BMI, hyperlipidemia (including LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides), hypertension (Systolic BP and Diastolic BP), albuminuria and clinical sites.

Table 3.

Odds of CAC overall and by self-reported history of CVD.

| Adjusted model ** | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Model | All | Without CVD* | With CVD* | |

| Age (per 1-y) | 1.09 (1.08– 1.09) | 1.09 (1.08–1.10) | 1.09 (1.08–1.10) | 1.07 (1.05–1.10) |

| Female Sex | 0.49 (0.41– 0.58) | 0.43 (0.35–0.53) | 0.36 (0.28–0.45) | 0.67 (0.45–1.00) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.72 (0.60– 0.87) | 0.48 (0.38–0.60) | 0.52 (0.40–0.69) | 0.35 (0.23–0.55) |

| Other | 0.83 (0.67– 1.02) | 0.94 (0.66–1.34) | 0.82 (0.54–1.25) | 1.09 (0.52–2.29) |

| Diabetes | 2.81 (2.37– 3.32) | 2.51 (2.05–3.07) | 2.39 (1.88–3.03) | 2.33 (1.52–3.56) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 3.44 (2.66– 4.45) | 1.82 (1.35–2.46) | 1.76 (1.26–2.45) | 1.31 (0.60–2.89) |

| Hypertension | 3.58 (2.75– 4.64) | 2.16 (1.58–2.97) | 2.22 (1.57–3.14) | 0.75 (0.29–1.96) |

| Current Smoking | 1.18 (0.90– 1.54) | 1.46 (1.07–2.00) | 1.44 (0.99–2.10) | 1.38 (0.76–2.48) |

| BMI (per 1-kg/m2) | 1.02 (1.00– 1.03) | 1.01 (1.00–1.03) | 1.01 (1.00–1.03) | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) |

| eGFR category | ||||

| <=30 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 2.86 (2.10– 3.90) | 1.49 (1.00–2.23) | 1.50 (0.93–2.42) | 1.02 (0.43–2.43) |

| 30–40 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 2.69 (1.98– 3.65) | 1.18 (0.81–1.73) | 1.21 (0.77–1.89) | 0.83 (0.36–1.96) |

| 40–50 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 2.63 (1.94– 3.56) | 1.24 (0.86–1.78) | 1.52 (0.99–2.34) | 0.57 (0.25–1.30) |

| 50–60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 1.70 (1.24– 2.33) | 1.19 (0.82–1.72) | 1.39 (0.91–2.14) | 0.65 (0.27–1.54) |

| =>60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Albuminuria | ||||

| =<30 mg/d | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 30–300 mg/d | 1.62 (1.31– 2.00) | 1.40 (1.11–1.78) | 1.46 (1.10–1.93) | 1.07 (0.65–1.73) |

| 300–1000 mg/d | 1.16 (0.90– 1.50) | 1.07 (0.79–1.46) | 1.16 (0.80–1.67) | 0.81 (0.44–1.47) |

| >=1000 mg/d | 1.26 (1.00– 1.60) | 1.22 (0.89–1.67) | 1.27 (0.87–1.86) | 0.69 (0.37–1.30) |

Values shown are odds ratio (95% confidence interval).

Model is adjusted for age, race, sex, diabetic status, current smoking status, hypertension, BMI, hyperlipidemia, albuminuria and clinical sites.

CVD history is self reported.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CAC, coronary artery calcification; CVD, cardiovascular disease

We also evaluated the data based upon the CKD-EPI equation in sensitivity analyses; Table S1–S3 show the baseline characteristics of the cohort by CKD-EPI eGFR, mean CAC scores for CKD-EPI eGFR category, and odds for association of CKD-EPI eGFR with CAC after multivariable analysis.

Discussion

Several small studies have demonstrated mixed results when evaluating the correlation between the prevalence and severity of CAC and the presence of earlier stages of CKD.4,5 Our study is among the first to demonstrate a graded relationship between severity of CKD and subclinical atherosclerosis (as assessed by CAC), independent of traditional risk factors and albuminuria. Given the consistent relationship between increasing CAC and worse cardiovascular outcomes, this has significant potential implications for care of these CKD patients. Arterial calcification in the intima of blood vessels occurs as part of atherosclerosis; calcification in the blood vessel media often happens in patients with diabetes mellitus or CKD.27 CT cannot differentiate between the two types of calcification, however, intimal (atherosclerosis) and medial (arterial stiffening) calcification have both been directly related to increased cardiovascular outcomes.

Prior studies evaluating the relationship between CAC and CKD have yielded inconsistent findings, possibly due to limited cohort size,4,5 or low prevalence of decreased kidney function among the study cohorts. Both MESA (the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis)28 and the Framingham Offspring Study29,30 have failed to demonstrate independent relationships between CKD and CAC. However both studies enrolled mostly patients with normal kidney function, so the population of patients with CKD was limited. For example, in the Framingham Offspring study, only 6.3% of 1,179 participants had CKD, so the power to determine a relationship was markedly reduced. MESA provided evidence that serum creatinine predicted CAC progression (there were 2.4 years, on average, between scans), but not baseline CAC.20 The Dallas Heart Study, 31 also evaluated the relationship between CKD and CAC among 2660 participants, but again, only 5.9% participants had CKD.32 In Dallas Heart Study patients with CKD stages 3–5, the odds of CAC scores >100 and >400 were 2.85 (95% CI, 0.92–8.80) and 8.35 (95% CI, 1.94–35.95), respectively, in the total population after adjustment for covariates (patients without CKD were the reference group).

Diabetes was certainly a contributing factor in the prevalence of CAC among these CKD patients. Prevalence of significant CAC (score >100) among participants with both diabetes and CKD was 50%, significantly greater than among those without diabetes (26%). Multiple population based studies have demonstrated that a score >100 was associated with a 10-fold risk of short-term cardiovascular events.11,33 and all-cause mortality,12 and the prevalence of these high scores in our study population was alarming. Current participants in CRIC are being followed for CVD events, however specific CRIC outcome data are not yet available.

Another important observation in this study is the relationship between CAC, CKD, and ethnicity.34 Previous studies have demonstrated that CAC levels27 and presence of CKD28 differ across various racial groups. MESA demonstrated significant ethnic differences in CAC among persons largely with normal kidney function,26 with African-Americans having significant lower CAC prevalence and severity than either Hispanics or Caucasian participants. The Framingham Offspring Study was largely of white, European descent, and the Dallas Heart Study had a low prevalence of ethnic minorities with CKD.

Merjanian et al demonstrated no graded relationship between CAC and CKD in diabetics35, while Qunibi25 documented that CAC in diabetic patients with various stages of CKD starts to occur in the early stages of kidney disease, and increases with lower levels of renal function. Qunibi et al demonstrated that the prevalence of CAC was at least 2-fold higher in patients with stages 4 and 5 CKD, as compared to those with stages 1 and 2 CKD. The percentages of patients with advanced and early CKD who had CAC scores ≥20 were 73% and 38%, respectively (P = 0.01).

Limitations of our study include use of eGFR for this analysis versus direct measurement, however this is a widely accepted and available marker in clinical practice. Another limitation is the lack of clinical cardiovascular outcome data, however follow up is ongoing, to better understand the exact implications of these elevated calcium scores in the CKD population. Treatment options need to be further explored, and CRIC is performing follow up scans in all participants in this substudy to allow for assessment of CAC progression.

In summary, we observed a strong and graded relationship between CAC and CKD in this study of 1908 participants with CKD. CAC becomes most significant when kidney function is below 30 eGFR. This is likely to have some physiopathological meaning since the kidney is able to regulate phosphate/calcium metabolism, the major interplayers in the etiology of CAC in kidney patients, as long as GFR is above 30 ml. The relationship remained highly significant among diabetics and non-diabetics, and among African-Americans and Whites, and has potential clinical and treatment implications. These findings support the recent guidelines36, which state that “known vascular/valvular calcification and its magnitude identify patients at high cardiovascular risk” and conclude that “the presence of vascular/valvular calcification should be regarded as a complementary component to be incorporated into the decision making of how to individualize treatment.” The CRIC study is ongoing, and will evaluate the relationship of calcifications with cardiovascular and renal events in CKD patients.

Supplementary Material

Table S1: Baseline characteristics of CAC analytic cohort by eGFR.

Table S2: Mean CAC scores for each category of CKD-EPI–derived eGFR.

Table S3: Unadjusted and adjusted ORs for association with CAC after multivariable analysis.

Acknowledgments

Members of the CRIC Study Group, by clinical centers, follow. University of Pennsylvania: Raymond R. Townsend MD (Principal Investigator); Borut Cizman MD; Virginia Ford MSN, RN; Kevin Mange MD, MSCE; Emile R. Mohler III MD. John Hopkins University/University of Maryland: Lawrence J. Appel MD, MPH (Principal Investigator); Brad Astor PhD, MPH; Jeanne Charleston RN; Wanda Corral RN; Thomas P. Erlinger MD, MPH; Jeffrey C. Fink MD; Edgar Miller MD; Neil R. Powe MD, MPH, MBA; Matthew Weir MD. Case Western Reserve University: Jackson T. Wright Jr. MD, PhD (Principal Investigator); Mahboob Rahman MD (Principal Investigator); Mark E. Dunlap MD; Martin J. Schreiber MD; Ashwini Sehgal MD. University of Michigan at Ann Arbor: Akinlolu O. Ojo MD, PhD (Principal Investigator); Denise Cornish-Zirker RN; A. Mark Fendrick BA, MD; Kenneth Jamerson MD; Friedrich K. Port MD, MS; Susan P. Steigerwalt MD; Bonnie Welliver RN; Eric Young MD. University of Illinois at Chicago: James P. Lash MD (Principal Investigator); John Daugirdas MD; Paul Vaitkus MD. Kaiser Permanente of Northern California/University of California, San Francisco: Alan S. Go MD (Principal Investigator); Lynn M. Ackerson PhD; Mark Alexander PhD; Glenn M. Chertow MD, MPH; Irina Gorodetskaya RD; Chi-yuan Hsu MD, MSc (Co- Principal Investigator); Carlos Iribarren MD, MPH, PhD; Nancy Jensvold MPH; Andrew J. Karter PhD; Joan C. Lo MD, MS; Juan Ordoñez MD, MPH. Tulane University: Jiang He MD, PhD (Principal Investigator); Vecihi Batutman MD; Karen DeSalvo MD; Vivian Fonseca MD; L. Lee Hamm MD (Co- Principal Investigator); Kenya Morris BS; Paul Muntner, PhD; Paolo Raggi MD; Paul K. Whelton MD, MSc. Scientific and Data Coordinating Center/University of Pennsylvania: Harold I. Feldman MD, MSCE (Principal Investigator); Denise Cifelli BS; Eunice D. Franklin-Becker MPH; Christina Gaughan MS; Marshall Joffe MD, PhD, MPH; Stephen E. Kimmel MD; Shiriki Kumanyika PhD, MPH; J. Richard Landis PhD (Co- Principal Investigator); Daniel J. Rader MD; Lee D. Randall BA; Richard Spielman PhD; J. Sanford Schwartz MD; Sharon X. Xie MS, PhD. The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK): John W. Kusek PhD (Project Officer); Thomas Hostetter MD.

Support: These studies were supported by NIH grants including R01 HL071739, R01-DK-067390, U01-DK-060984, and NIH/NCR grants UL1-RR024134, UL1 RR-025005, M01 RR-16500, UL1 RR-024989, M01 RR-000042, UL1 RR-024986, UL1RR029879, M01 RR-05096, UL1 RR-024131.

Footnotes

Note: The supplementary material accompanying this article (doi:_______) is available at www.ajkd.org

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Budoff MJ, Achenbach S, Blumenthal RS, Carr JJ, Goldin JG, Greenland P, Guerci AD, Lima JAC, Rader DJ, Rubin GD, Shaw LJ, Wiegers SE. Assessment of Coronary Artery Disease by Cardiac Computed Tomography, A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association Committee on Cardiovascular Imaging and Intervention, Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention, and Committee on Cardiac Imaging, Council on Clinical Cardiology. Circulation. 2006;114(16):1761–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.178458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenland P, Bonow RO, Brundage BH, Budoff MJ, Eisenberg MJ, Grundy SM, Lauer MS, Post WS, Raggi P, Redberg RF, Rodgers GP, Shaw LJ, Taylor AJ, Weintraub WS. ACCF/AHA 2007 clinical expert consensus document on coronary artery calcium scoring by computed tomography in global cardiovascular risk assessment and in evaluation of patients with chest pain. Circulation. 2007;115(3):402–26. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA..107.181425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Budoff MJ, Shaw LJ, Liu ST, Weinstein SR, Mosler TP, Tseng PH, Flores FR, Callister TQ, Raggi P, Berman DS. Long-Term Prognosis Associated With Coronary Calcification: Observations From a Registry of 25,253 Patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1860–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsuoka M, Iseki K, Tamashiro M, et al. Impact of high coronary artery calcification score (CACS) on survival in patients on chronic hemodialysis. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2004;8:54–8. doi: 10.1007/s10157-003-0260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Block GA, Raggi P, Bellasi A, Kooienga L, Spiegel DM. Mortality effect of coronary calcification and phosphate binder choice in incident hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2007;71:438–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raggi P, Boulay A, Chasan-Taber S, Amin N, Dillon M, Burke SK, Chertow GM. Cardiac calcification in adult hemodialysis patients. A link between end-stage renal disease and cardiovascular disease? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:695–701. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01781-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodman WG, Goldin J, Kuizon BD, Yoon C, Gales B, Sider D, Wang Y, Chung J, Emerick A, Greaser L, Elashoff RM, Salusky IB. Coronary-artery calcification in young adults with end-stage renal disease who are undergoing dialysis. New England J Med. 2000;342:1478–1483. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Budoff MJ, Kessler P, Gao YL, Qunibi W, Moustafa M, Mao SS. The Interscan Variation of CT Coronary Artery Calcification Score Analysis of the Calcium Acetate Renagel Comparison (CARE)-2 Study. Acad Radiol. 2008;15:58–61. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehrotra R, Budoff M, Christenson P, Ipp E, Takasu J, Gupta A, Norris K, Adler S. Determinants of coronary artery calcification in diabetics with and without nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2004;66:2022–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehrotra R, Westenfeld R, Christenson P, Budoff M, Ipp E, Takasu J, Guta A, Norris K, Ketteler M, Adler S. Serum Fetuin-A in non-dialyzed patients with diabetic nephropathy: Relationship with coronary artery calcification. Kidney International. 2005:1070–1077. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenland P, Bonow RO, Brundage BH, Budoff MJ, Eisenberg MJ, Grundy SM, Lauer MS, Post WS, Raggi P, Redberg RF, Rodgers GP, Shaw LJ, Taylor AJ, Weintraub WS. ACCF/AHA 2007 clinical expert consensus document on coronary artery calcium scoring by computed tomography in global cardiovascular risk assessment and in evaluation of patients with chest pain. Circulation. 2007;115:402–26. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA..107.181425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Budoff MJ, Shaw LJ, Liu ST, Weinstein SR, Mosler TP, Tseng PH, Flores FR, Callister TQ, Raggi P, Berman DS. Long-Term Prognosis Associated With Coronary Calcification: Observations From a Registry of 25,253 Patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1860–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuoka M, Iseki K, Tamashiro M, et al. Impact of high coronary artery calcification score (CACS) on survival in patients on chronic hemodialysis. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2004;8:54–8. doi: 10.1007/s10157-003-0260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiu YW, Adler SG, Budoff MJ, Takasu J, Ashai J, Mehrotra R. Coronary artery calcification and mortality in diabetic patients with proteinuria. Kidney Int. 2010;77:1107–14. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oh J, Wunsch R, Turzer M, Bahner M, Raggi P, Querfeld U, Mehls O, Schaefer F. Advanced coronary and carotid arteriopathy in young adults with childhood-onset chronic renal failure. Circulation. 2002;106:100–105. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000020222.63035.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chertow GM, Burke SK, Raggi P. Sevelamer attenuates the progression of coronary and aortic calcification in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2002;62:245–252. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakamura S, Ishibashi-Ueda H, Niizuma S, Yoshihara F, Horio T, Kawano Y. Coronary calcification in patients with chronic kidney disease and coronary artery disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1892–900. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04320709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldman HI, Appel LJ, Chertow GM, et al. The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study: Design and Methods. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:S148–S153. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000070149.78399.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lash JP, Go AS, Appel LA, et al. Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study: Baseline Characteristics and Associations with Kidney Function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1302–1311. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00070109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461– 470. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:S1–S266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coresh J, Astor BC, McQuillan G, Kusek J, Greene T, Van Lente F, Levey AS. Calibration and random variation of the serum creatinine assay as critical elements of using equations to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:920 –929. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.32765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mao SS, Pal RS, McKay CS, Gao YG, Gopal A, Ahmadi N, Child J, Carson S, Takasu J, Sarlak B, Bechmann D, Budoff MJ. Comparison of Coronary Artery Calcium Scores Between Electron Beam Computed Tomography and 64-Multidetector Computed Tomographic Scanner. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2009;33:175–8. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e31817579ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carr JJ, Nelson JC, Wong ND, et al. Calcified coronary artery plaque measurement with cardiac CT in population-based studies: Standardized protocol of Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Radiology. 2005;234:35–43. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2341040439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, et al. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:827–832. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tong LL, Mehrotra R, Shavelle DM, Budoff M, Adler S. Poor correlation between coronary artery calcification and obstructive coronary artery disease in an end-stage renal disease patient. Hemodial Int. 2008;12:16–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2008.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ix JH, Katz R, Kestenbaum B, Fried LF, Kramer H, Stehman-Breen C, Shlipak MG. Association of mild to moderate kidney dysfunction and coronary calcification. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:579–85. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007070765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parikh NI, Hwang SJ, Larson MG, Hoffmann U, Levy D, Meigs JB, O’Donnell CJ, Fox CS. Indexes of Kidney Function and Coronary Artery and Abdominal Aortic Calcium (from the Framingham Offspring Study) Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:440–443. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fox CS, Larson MG, Keyes MJ, et al. Kidney function is inversely associated with coronary artery calcification in men and women free of cardiovascular disease: The Framingham Heart Study. Kidney Int. 2004;66:2017–2021. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kramer H, Toto R, Peshock R, Cooper R, Victor R. Association between chronic kidney disease and coronary artery calcification: The Dallas Heart Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:507–513. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004070610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qunibi WY, Abouzahr F, Mizani MR, Nolan CR, Arya R, Hunt KJ. Cardiovascular calcification in Hispanic Americans (HA) with chronic kidney disease (CKD) due to type 2 diabetes. Kidney Int. 2005;68:271–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Budoff MJ, Nasir K, McClelland RL Detrano R, Wong N, Blumenthal RS, Kondos GT, Kronmal RA. Coronary calcium predicts events better with absolute calcium scores than age-gender-race percentiles – The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:345–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bild DE, Detrano R, Peterson D, et al. Ethnic differences in coronary calcification: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Circulation. 2005;111:1313–1220. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157730.94423.4B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Merjanian R, Budoff MJ, Adler S, et al. Coronary artery, aortic wall, and valvular calcification in nondialyzed individuals with type 2 diabetes and renal disease. Kidney Int. 2003;64:263–271. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD–MBD Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD–MBD) Kidney International. 2009;76 (Suppl 113):S1–S130. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: Baseline characteristics of CAC analytic cohort by eGFR.

Table S2: Mean CAC scores for each category of CKD-EPI–derived eGFR.

Table S3: Unadjusted and adjusted ORs for association with CAC after multivariable analysis.