Abstract

Biocalcification of collagen matrices with calcium phosphate and biosilicification of diatom frustules with amorphous silica are two discrete processes that have intrigued biologists and materials scientists for decades. Recent advancements in the understanding of the mechanisms involved in these two biomineralisation processes have resulted in the use of biomimetic strategies to replicate these processes separately using polyanionic, polycationic or zwitterionic analogues of extracellular matrix proteins to stabilise amorphous mineral precursor phases. To date, there is a lack of a universal model that enables the subtleties of these two apparently dissimilar biomineralisation processes to be studied together. Here, we utilise the eggshell membrane as a universal model for differential biomimetic calcification and silicification. By manipulating the eggshell membrane to render it permeable to stabilised mineral precursors, it is possible to introduce nanostructured calcium phosphate or silica into eggshell membrane fibre cores or mantles. We provide a model for infiltrating the two compartmental niches of a biopolymer membrane with different intrafibre minerals to obtain materials with potentially improved structure-property relationships.

Keywords: apatite, biomineralisation, silica, membrane

1. Introduction

Calcification of the eggshell is among the most rapid biomineralisation processes known, with precise spatiotemporal control of its sequence of events [1]. As the egg yolk traverses the oviduct, it acquires egg white in the magnum followed by deposition of a fibrous eggshell membrane (ESM) in the isthmus. In the distal part of the isthmus, proteoglycan-rich mammillary knobs are secreted over the ESM to serve as sites for deposition of columnar calcite crystals that form the palisade layer of the eggshell [2]. The ESM is divided into an inner interlacing network of thinner fibres and an outer network of thicker fibres. Each fibre is traditionally conceived to be made up of a collagen-rich core and a glycoprotein-rich mantle [2,3]. Fibre cores from the outer ESM contain predominantly type I collagen while those from the inner ESM contain types I and V collagen [1]. Type X collagen has also been identified from both membrane layers and is postulated to function as a mineralization inhibitor to prevent the underlying egg white and yolk from being mineralized [4]. Despite immunohistochemical identification of these collagen variants, fibre cores from the ESM appear homogeneously stained at the electron microscopical level and lack substructural fibrillar characteristics or the 67-nm cross striations seen in fibrillar collagen [5]. This may be due to masking of these avian collagens with a cysteine-rich eggshell membrane protein (CREMP) that contains multiple disulphide bonds [6].

Scientists find biomineralisation intriguing because amorphous and crystalline structures created through interactions between proteins and minerals are considerably more advanced than what may be achieved by contemporary materials engineering [7,8]. As the ESM does not mineralise in-situ, it has been utilised as a biomineralisation model [1,9] or as a biological template for surface modification of crystal growth [10–12]. However, biomimetic mineralisation within the ESM matrix has not yet been achieved even when pepsin is employed to remove its purported mineralisation inhibition components [4]. Nevertheless, mineralisation of pepsin pre-treated ESMs in the presence of a biomimetic analogue of matrix phosphoproteins resulted only in the deposition of extrafibre apatite crystals on the ESM surface [8].

The recent discovery of the involvement of calcium phosphate prenucleation clusters has considerably advanced our understanding of the biomineralisation of collagen [13]. Using polycarboxylic acid analogues of extracellular matrix proteins to stabilise prenucleation clusters-derived amorphous calcium phosphate as plastic, liquid-like precursor phases [14], it is possible to take advantage of the templating properties of type I collagen to introduce intrafibrillar apatite crystallites into collagen fibrils [15]. Likewise, biosilicification of diatom frustules is under the precise control of highly-phosphorylated biomolecules and long-chain polyamines that produce plastic protein-stabilised silica phases [16,17]. In this work, we utilised the eggshell membrane as a universal biomineralisation model to test the hypothesis that it is possible to differentially introduce biominerals into the different compartmental niches of a biopolymer membrane (i.e. calcium phosphate in ESM fibre cores and silica in ESM fibre mantles) by using biomimetic analogues to create stabilised amorphous phases of the corresponding mineral.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Retrieval of eggshell membranes

Eggshell membranes were obtained from commercial breeding lines of Gallus gallus. The outer membranes were carefully removed using forceps and washed with Milli-Q water (18.2 mΩ-cm). The membranes were stored in water to avoid dehydration and used within 24 hours after harvesting. The ESMs were cut while immersed in water into 1 cm × 1 cm specimens for the biomineralisation experiments.

2.2 Biocalcification

Polyacrylic acid-stabilised amorphous calcium phosphate precursors were prepared using a concentrated calcium phosphate mineralising medium containing 10.5 mM CaCl2·2H2O and 6.3 mM K2HPO4 in HEPES buffer (pH 7.4). They were prevented from spontaneous precipitation by incorporating 500 μg/mL polyacrylic acid (Mw 1800, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as an apatite nucleation-inhibiting agent. The concentration of polyacrylic acid used was based on the minimal amount required for the solution to remain stable and visibly clear for at least 1 month. This was monitored with optical density measurements taken at different time intervals with a 96-well plate reader at 650 nm.

Prior to biocalcification, ESM specimens were treated with 1.25 N 3-mercaptopriprionic acid (MPA, Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in 10% acetic acid for 3 hours. After rinsing with Milli-Q water, they were incubated in a 5 wt% sodium tripolyphosphate solution (Mw 367.9, Sigma-Aldrich) at room temperature for 1 hour and further rinsed with Milli-Q water. The phosphorylated ESMs were then calcified by immersing each ESM square in 1 mL of stabilised amorphous calcium phosphate precursors at 37 °C for 14 or 28 days, with daily change of the calcifying medium.

2.3 Biosilicification

Choline-stabilised silicic acid precursors were prepared using a 3% silicic acid stock solution. The latter was prepared by mixing Silbond® 40 (40% hydrolysed tetraethyl orthosilicate; Silbond Corp., Weston, MI, USA), absolute ethanol, water and 37% HCl in the molar ratios of 1.875: 396.79: 12.03: 0.0218 (mass ratio 15: 182.8: 2.167: 0.008) for 1 hour at room temperature to complete the hydrolysis of tetraethyl orthosilicate into orthosilicic acid and its oligomers. The 3% silicic acid solution was then mixed with 0.07 M choline chloride (Mw 139.6m, Sigma-Aldrch) in a 1:1 volume ratio (final pH = 5) under vibration for 1 min. After centrifuging the mixture at 3000 RPM, the supernatant containing choline-stabilised silicic acid was collected for the biosilicification experiments. The MPA-treated ESMs were immersed in a 5 wt% sodium tripolyphosphate solution for 1 hour and rinsed thoroughly with Milli-Q water. Each ESM square was silicified in 1 mL of choline-stabilized silicic acid at 37 °C for 4 days with daily change of the silicifying solution.

2.4 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

To examine the surface morphology of ESMs before and after MPA pre-treatment, the specimens were desiccated in anhydrous calcium sulfate, sputter-coated with gold/palladium and examined using a field emission-scanning electron microscope (XL-30 FEG; Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) at 10 kV.

2.5 Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Eggshell membranes before and after biomineralisation were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde, post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in an ascending ethanol series (50–100%), immersed in propylene oxide and embedded in epoxy resin. Ninety nanometre thick sections were prepared and examined using a JSM-1230 TEM (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) at 110 kV. Intact or MPA pre-treated specimens without biomineralisation were examined after staining with 2% uranyl acetate and Reynold’s lead citrate. Mineralised specimens were examined unstained. Selected area electron diffraction (SAED) was performed on the mineralised.

2.6 Attenuated total reflection – Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR)

Each ESM specimen was desiccated with anhydrous calcium sulphate for 24 hours prior to spectrum acquisition. A Nicolet 6700 FT-IR spectrophotometer (ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with an ATR setup was used to collect infrared spectra between 4,000-400 cm−1 at 4 cm−1 resolution using 32 scans.

2.7 Amino acid analyses

Amino acid analyses were performed on untreated ESMs as well as ESMs that were subjected to 3 hours and 5 hours of MPA pre-treatment to determine if there were common trends in the changes of amino acid profiles. A L8900 Analyser (Hitachi, Schaumburg, IL, USA) equipped with a Hitachi AAA Special Analysis Column (855–4516) was employed for the analyses. The 16 common amino acids together with hydroxyproline, hydroxylysine and cyst(e)ine were analysed. The analyser was calibrated using standard amino acid stock solution (AAS18, Sigma-Aldrich) and additional amino acid standards: trans-4-hydroxy-L-proline, hydroxylysine, L-cysteic acid and pyridylethyl-L-cysteine. L-norleucine was used as the internal standard (Sigma-Aldrich).

The ESMs were hydrolysed with 6N HCL/2% phenol at 110°C for 22 hours under vacuum into individual amino acid residues. A defined amount of the norleucine internal standard was added to each sample prior to hydrolysis. Cyst(e)ine was oxidised with H2O2 and formic acid (1:10 v/v) to cysteic acid prior to analysis. The individual amino acids were separated by ion-exchange chromatography with measurement of the ninhydrin chromophore. Data analysis was performed using the EZChrom Elite software (Version 3.1E; Scientific Software International Inc., Lincolnwood, IL, USA). The data were normalised to the known concentration of the internal standard.

2.8 Electron tomography, serial sectioning and 3-D reconstruction

Electron tomography was performed with 200 nm thick unstained epoxy resin-embedded sections using a Tecnai G2 STEM (FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA) at 200 kV. Tomographic images were taken from +30° to −30° at 1° increment. Tilt series were created using the Gatan Digital Micrograph software. Image alignment was performed using Reconstruct Version 1.1.0.0. (http://synapses.clm.utexas.edu/tools/reconstruct/reconstruct.stm). Three-dimensional reconstruction, segmentation and visualisation of the 3D volume were performed using Amira 5.3.3. (Visage Imaging Inc., Andover MA, USA). For serial sectioning, 120–130 sixty nm thick sections were prepared for TEM imaging, aligned using the Reconstruct software and reconstructed for visualisation using the Amira software programme.

2.9 Scanning transmission electron microscopy-energy dispersive X-ray analysis (STEM-EDX)

Elemental analysis of the mineralised ESMs was performed on the thin sections prepared previously for TEM using the FEI Tecnai G2 STEM at 200 kV. Spectrum acquisition and elemental mapping were conducted using an Oxford Instruments INCA x-sight detector. Elemental mappings were acquired with the FEI TIA software using a spot dwell time of 300 msec with drift correction performed after every 30 images.

2.10 Nanoindentation

Control (non-mineralised) and silicified ESMs were prepared by placing small portions (3×3 mm) of the membrane on a glass cover slip. The hydrated specimens were covered within droplets of Milli-Q water to minimise moisture loss. Mechanical properties of the specimens were evaluated by quasi-static indentation using an instrumented nanoindenter (Hysitron Tribinderter 900, Minneapolis, MN, USA) with a 100 μm radius cono-spherical diamond tip indenter. A standard trapezoidal profile was used including a maximum load of 100 μN, indentation hold time of 5 sec, and loading and unloading rates of 20 μN/sec. An initial offset load of 10 μN was used for identifying contact and initialise the indentation process. For each specimen, 10 indentations were performed to characterise the mechanical behaviour. The load-displacement curves generated for the individual indentations were corrected for the offset force, and the unloading response was used to estimate the reduced modulus and hardness according to the Oliver and Pharr approach [18]. The spherical tip function utilised in estimating the properties was determined using a single-crystal aluminum calibration sample over the range in indentation depths experienced in evaluating the membrane specimens. As the data obtained for the reduced modulus and hardness of the specimens were not normally distributed, each data set was statistically analysed with Mann Whitney rank sum test at α = 0.05.

3. Results

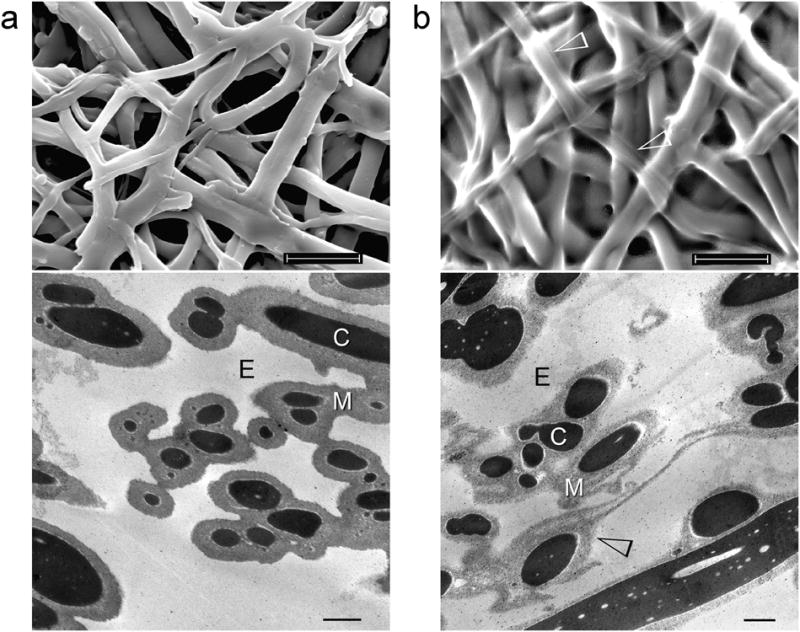

Figure 1a represents SEM and TEM micrographs of untreated outer ESM fibres. Each fibre is 1–4 μm in diameter and consists of an inner highly electron-dense core and an outer less-electron-dense mantle. In control mineralisation experiments performed on pepsin pre-treated outer ESMs, mineral deposition was exclusively observed on the surface of the ESM fibres, with no evidence of intrafibre mineralisation (Supporting Information S1; Fig. S1). When the outer ESMs were pre-treated with 1.25 N MPA in 10% acetic acid at 70 °C for 3 hours prior to the biocalcification or biosilification experiments, the fibre mantles became more porous (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

SEM (top) and stained TEM images (bottom) of the outer eggshell membrane (ESM). a, Intact, untreated membrane fibres are 1–4 μm in diameter and separated by extrafibre spaces (E). Each fibre consists of a collagen-rich core (C) that is surrounded by a glycoprotein-rich mantle (M). b, After treatment with 3-mercaptoproprionic acid (MPA), the fibre mantle becomes more porous (open arrowheads). In both cases, fibrillar substructure cannot be discerned from the stained collagen-rich fibre core. Scale bars: SEM – 10 μm, TEM – 1 μm.

Examination of untreated ESMs by ATR-FTIR revealed collagen-associated peaks as well as additional IR bands that were probably associated with noncollagenous proteins and glycoprotein components of the fibre core and mantle. (Supporting Information S2; Fig. S2a). After pre-treatment with MPA, alterations in the infrared spectrum of ESMs occurred predominantly in the 1,000–1,200 cm−1 region (Supporting Information S2; Fig. S2b). Amino acid analyses indicated an increase in reduced cyst(e)ine concentration of the ESMs after MPA pre-treatment despite reductions in the content of most amino acids (Supporting Information S3).

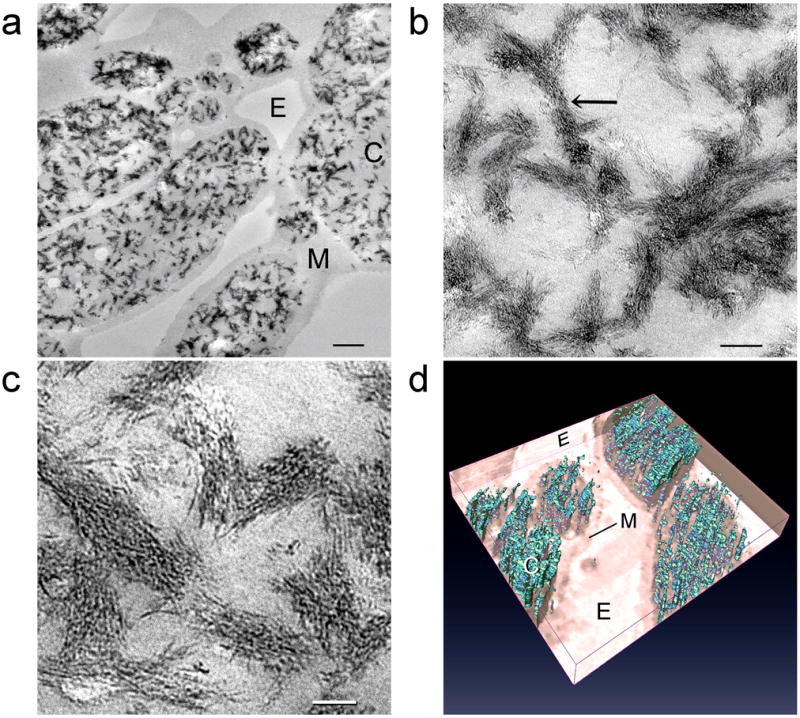

Figure 2 shows the initial stage of differential biocalcification of ESM fibre cores after 14 days of immersion in the mineralising medium. Calcified fibrils ~50 nm in diameter were seen within the fibre cores despite their lack of stainable fibrillar substructures [5]. For each calcified fibril, minerals were deposited in the form of intertwining electron-dense strands that resemble those observed after the microfibrillar compartments of type I collagen were infiltrated by amorphous calcium phosphate [15,19]. Electron tomography of the bicalcified fibre cores (Fig. 2d) is less revealing due to the limitation that only a fraction of a 1–4 μm diameter ESM fibre could be visualised even with 200 nm thick sections. Nevertheless, a 3-dimensional array of mineral deposits can be seen after reconstruction of the aligned images. Selected area electron diffraction performed on the calcified fibrils produced a diffuse diffraction pattern (not shown), indicating that the intrafibrillar amorphous calcium phosphate had not been transformed into apatite at this stage. Elemental mappings with STEM-EDX confirmed the presence of calcium and phosphorus within the fibre cores (Fig. 3a). A small amount of phosphorus could also be detected within the fibre mantles that could be derived from the polyphosphate used for ESM phosphorylation.

Figure 2.

Unstained TEM images showing the initial stage of differential biocalcification of the fibre cores in MPA pre-treated ESMs after 14 days. a, An overall view of the fibres with partially-calcified cores (C) and uncalcified mantles (M). E: extrafibre space. Scale bar: 500 nm. b, Higher magnification of the ~50 nm diameter calcified core fibrils. Scale bar: 100 nm. c, Mineral deposition in the form of microfibrillar strands within the calcified fibrils. Scale bar: 50 nm. d, Three-dimensional reconstructed profile of the calcium phosphate deposits (cyan) within the fibre core. The fibre mantle was completely devoid of mineral deposits.

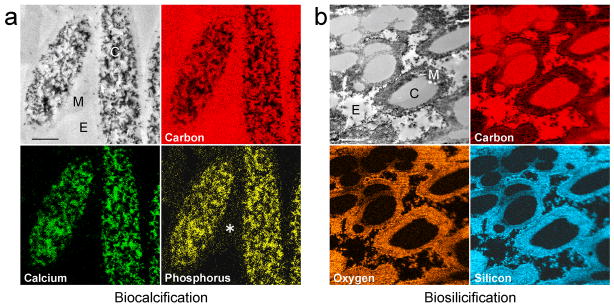

Figure 3.

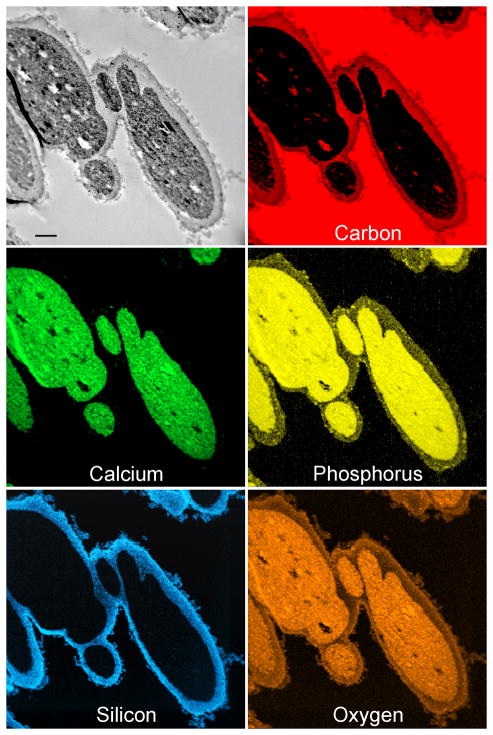

STEM-EDX mappings of elemental distributions within MPA pre-treated ESMs. a, Upper left in “a” after 14 days of biocalcification when individual mineralised fibrils can still be recognised within the fibre cores (C). The mineralised fibrils yield strong signals of calcium and phosphorus. Fibre mantle (M) and extrafibre spaces (E) are devoid of calcium. Phosphorus is co-localised with calcium in the fibre cores but is also detected from the fibre mantle (asterisk). Scale bar: 1 μm. b, Upper left in “b” after 4 days of biosilicification, strong signals of oxygen and silicon can be detected within the fibre mantles (M). The fibre cores (C) are devoid of silicon. E: extrafibre space. Scale bar: 1 μm.

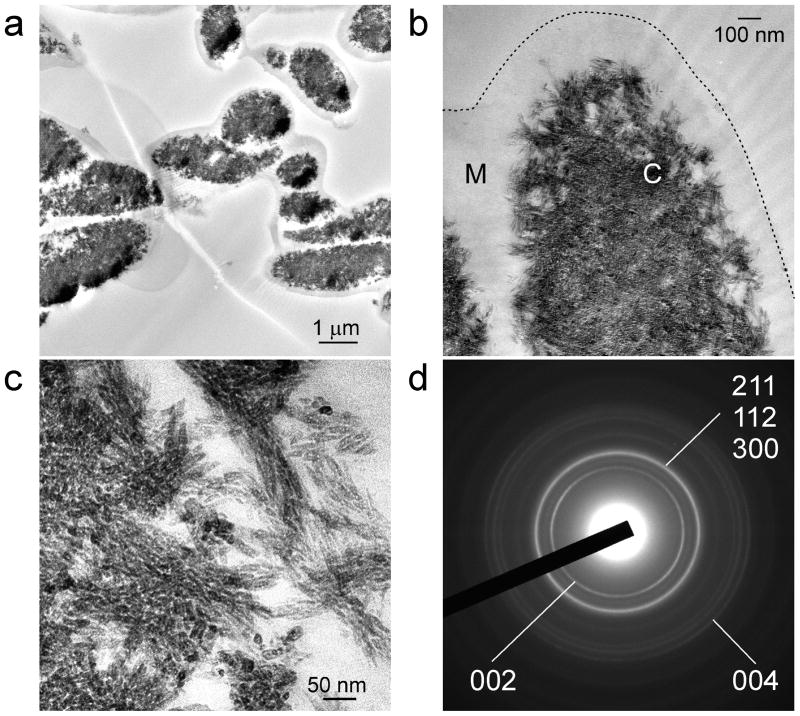

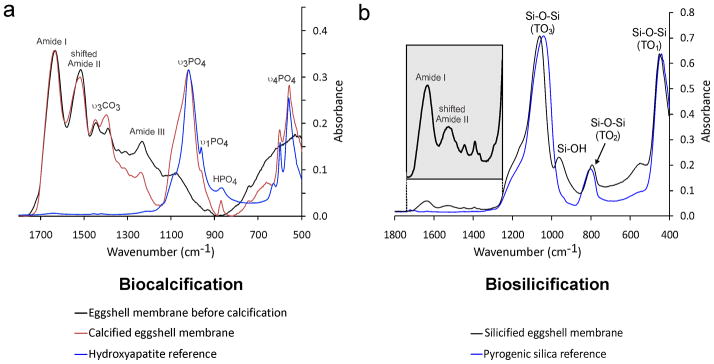

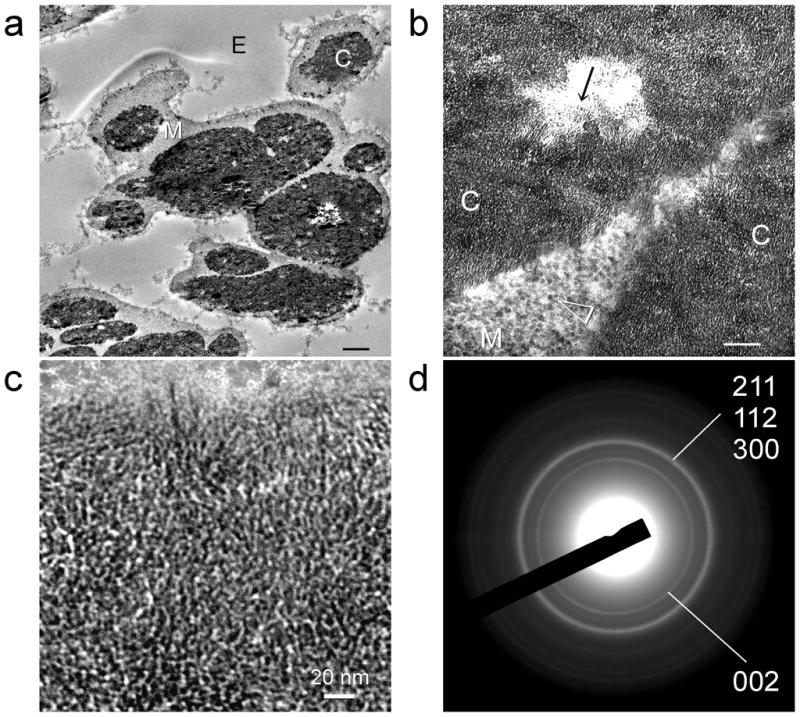

Figures 4a–c represent the results of a more advanced stage of biocalcification after 28 days of immersion in the mineralising medium. The fibre cores became almost completely calcified while the fibre mantles remained uncalcified. With such heavy calcification, fibrillar substructures were no longer observed. However, discrete mineral platelets were found within the calcified fibre cores. Conversion of amorphous calcium phosphate into apatite was confirmed using selected area electron diffraction (Fig. 4d) as well as ATR-FTIR. The latter shows apatite-associated peaks within the calcified ESM (Fig. 5a).

Figure 4.

Unstained TEM images showing a more advanced stage of differential biocalcification of the fibre cores in MPA pre-treated ESMs after 28 days. a, An overall view of the highly calcified ESM. Scale bar: 500 nm. b, Higher magnification of the heavily calcified fibre core (C). Fibrillar structures are obscured by dense mineral aggregation. The mantle (M), demarcated from the extrafibre space by the dotted line, was devoid of minerals. Scale bar: 100 nm. Scale bar: 50 nm. c, Mineral nanoplatelets (ca. 20–25 nm along their C-axis) that are found within the calcified fibre core. d, Selected area electron diffraction of the mineral platelets reveals ring patterns that are characteristic of apatite.

Figure 5.

Infrared spectra of ESMs before and after biomineralisation. a, ESM infrared spectra before and after 28 days of biocalcification. Uncalcified ESM demonstrates Amide I (~1635 cm−1) and Amide III peaks (~1240 cm−1) characteristic of collagen. The Amide II collagen peak (~1527 cm−1) is shifted to a lower wavenumber compared with pure type I collagen (Supporting Information S2). ESM spectra are normalised along their Amide I peaks. The hydroxyapatite reference spectrum is normalised to the calcified ESM spectrum along their apatite υ3PO4 peak (~1020 cm−1). The υ3CO3 peak (1398 cm−1) in the calcified ESM is indicative of the presence of carbonated apatite. b, Infrared spectrum of the ESM after 4 days of biosilicification. The three main peaks characteristic of Si-O-Si vibrational modes are detected around 1041 cm−1 (transverse optical - TO3 mode), 802 cm−1 (TO2 mode) and 453 cm−1 (TO1 mode). Pyrogenic silica used as the silica reference is normalised to the Si-O-Si TO3 peak of the silicified ESM. The silica peak at 960 cm−1 associated with the silicified ESM is attributed to the Si-OH stretching vibrations of hydrated amorphous silica.

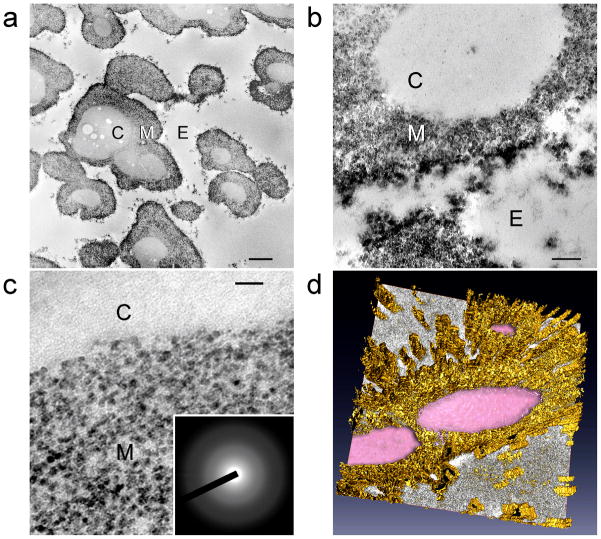

Unstained TEM of the biosilicified ESM shows that silica nanoparticles were predominantly deposited in the fibre mantles (Fig. 6a–c). The amorphous silica nanoparticles were approximately 10 nm in diameter. Three-dimensional reconstruction of multiple electron tomography images derived from a slice of the biosilicified ESM is shown in Fig. 6d. As electron tomography is incapable of showing the full thickness of a 1–4 μm diameter ESM fibre, serial sectioning was found to be a better alternative for depicting the extent of mantle silicification within the large, interconnecting mineralised fibres (Supporting Information S4, Fig. S4). A movie showing the continuity of the silicified ESM mantles can be found in Supporting Information S4 as mantle.mov. These silicified structures resemble diatom frustules in that a hollow silica shell is formed around a soft organic core [17]. Elemental analysis of the biosilicified ESM by STEM-EDX indicates that silicon is localised within the fibre mantle (Fig. 3b). The presence of silica-associated peaks within the biosilicified ESM was further confirmed using ATR-FTIR (Fig. 5b).

Figure 6.

Unstained TEM images of differential biosilicification of the fibre mantles in MPA pre-treated ESMs after 4 days. a, Heavy silicification within the fibre mantle (M). The extrafibrillar space (E) is also sparsely filled with silica nanoparticle clusters. C: fibre core. Scale bar: 1 μm. b, Dense aggregation of silica nanoparticles within the fibre mantle. The fibre core is devoid of silica. Scale bar: 200 nm. c, Silica nanoparticles (ca. 10 nm in diameter) within the silicified mantle. Scale bar: 50 nm. Inset: SAED of the silicified fibre mantle reveals the amorphous nature of the silica nanoparticles. d, Three-dimensional reconstructed profile of the silica deposits (yellow) within the fibre mantle. The fibre core (pink) is devoid of silica deposits. Gray: extrafibre spaces.

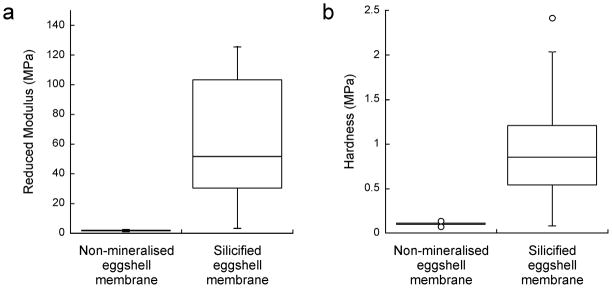

Quasi-static nanoindentation results of the non-mineralised and silicified ESMs are shown in Fig. 7. The reduced modulus of hydrated ESMs after biosilicification (72.84±66.56 MPa) was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than that of hydrated, non-mineralised ESMs (1.84±0.33 MPa). Likewise, the hardness of hydrated ESMs after biosilicification (0.97±0.66 MPa) was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than that of hydrated, non-mineralised ESMs (0.11±0.02 MPa).

Figure 7.

Box plots comparing the quasi-static mechanical properties of non-mineralized vs silicified ESMs based on nanoindentation. a. Reduced modulus. b. Hardness.

4. Discussion

Eggshell membrane is an inutile hatchery by-product that is a rich source of collagen and other proteins. In its natural form, this biopolymer network provides a non-mineralised platform for outward mineralisation of the eggshell while preventing inward mineralisation of the egg white and yolk. Preponderance of disulphide-rich CREMPs [6] and covalent lysine-derived cross-links [20] may have caused the ESMs to remain impermeable to amorphous mineral precursors. Reducing agents such as MPA [21], dithiothreitol [6] and thioglycolate [22] have been used for reducing disulphide linkages of ESMs. Here, we demonstrate that by rendering the ESM permeable with MPA and by further treating it with a polyphosphate analogue of matrix phosphoproteins, it is possible to introduce calcium phosphate or silica into ESM fibres at the nanoscopical scale by using amorphous precursor phases of the corresponding mineral. Based on the results of the amino acid analyses, the increased permeability of MPA pre-treated ESMs is attributed to the combined results of protein extraction and cleavage of cystine disulphide bonds. We initially attempted to remove the mineralisation inhibiting components of the ESM by incubating MPA pre-treated membranes in pepsin for different time periods. However, MPA pre-treatment alone was found to be sufficient for the ESMs to be mineralised. Moreover, combined MPA pre-treatment and pepsin digestion adversely altered the handling characteristics of the ESMs and resulted in aggressive dissolution of the collagen-rich fibre cores. Hence, all biomineralisation experiments were subsequently performed without pepsin digestion.

Biominerals are perfect examples of organic-inorganic hybrid composites whose structures and properties are modified by extracellular matrix proteins. These hybrid composites are created by non-classical crystallisation pathways that utilise amorphous mineral precursor phases in mesoscale bottom-up approaches [23]. Calcium and phosphate ions from a calcifying medium self-assemble into stable particulate units known as pre-nucleation clusters. In the presence of polyanionic analogues of matrix proteins, these pre-nucleation clusters further condense into fluidic amorphous calcium phosphate precursors that are capable of infiltrating the intrafibrillar compartments of type I collagen [13]. Contrary to previous beliefs that type I collagen provides a passive depot for apatite deposition, there is a recent paradigm shift that supports an active role of type I collagen in templating intrafibrillar apatite nucleation and growth [15]. This is achieved via electrostatic interaction of sites with net positive charges along the collagen fibril with polyanion-stabilised amorphous calcium phosphate precursors. As there was no fibrillar collagen within the fiber core to act as mineralisation templates, we incubated MPA pre-treated ESMs in 5 wt% sodium tripolyphosphate to introduce phosphate residues into the collagen via an ionic cross-linking mechanism [24]. Sodium tripolyphosphate has previously been shown to be as an effective biomimetic analogue of matrix phosphoproteins involved in biomineralisation of collagen [19]. The amorphous calcium phosphate precursors were prevented from spontaneous precipitation by incorporating polyacrylic acid as an apatite nucleation-inhibiting agent [19,24]. Using dynamic light scattering and zeta potential measurements, these precursors exhibited an average hydrodynamic diameter of 14.95±1.0 nm with a polydispersity index of 0.35±0.01 and a net negative surface charge of −32.5±3.0 mV (Supporting Information S5).

Surprisingly, calcified fibrils were seen within the fibre cores during the initial stage of biocalcification, despite their lack of stainable fibrillar substructures. This suggests that fibrillar collagens are invariably present within the ESM fibre cores. Their inability to be identified by staining may be due to the formation of complex alloys with other nonfibrillar collagen or not-yet-identified collagen types such as the FACITs (fibril-associated collagen with interrupted triple helix) [25]. These additional collagen entities may interact with proteins containing the disulphide-rich CREMP motifs [6] via their terminal non-helical domains. Pre-treatment of ESMs with MPA could have disrupted these interactions, enabling amorphous calcium phosphate precursors to infiltrate the water compartments of the fibrillar collagen.

Biosilicification of diatom cell walls and sponge spicules represents Nature’s ingenious mechanism for polymerisation of nano-structured silica from silicic acid [8,26]. These biosilica structures are composites containing zwitterionic proteins and long chain polyamines in addition to silica. Biogenesis of silica in diatoms is catalysed by silaffins that are characterized by the presence of polyamines as well as phosphorylation, N-methylation and hydroxylation of amino acid residues [17]. Attempts have been made to synthesise nanostructured silica materials using biomimetic catalysts such as polyamines or amine-terminated dendrimers [27,28]. Catechol (1,2-dihydroxybenzene)-stabilized silicic acid complex acts as a silica precursor for silicification under simulated biological conditions [29]. In our experiments, we employed choline-stabilized orthosilicic acid (ch-OSA) complex as the silica precursor. The positively-charged quaternary ammonium group in choline (2-hydroxy-N,N,N-trimethylethanaminium chloride) interacts with oxygen in silicic acid to form a relatively stable complex [30]. As a dietary supplement, ch-OSA reduces bone turnover in overiectomized rats [31] and in human clinical trials [32].

We serendipitously discovered that the ESM mantle serves as a template for biocatalytic polymerisation of silicic acid into nano-silica. In biomimetic silicification, polycations such as polyallylamine and phosphate are simultaneously required to create micro-phase separations for silica to precipitate [17]. However, no polyallylamine was utilised in the present work. Chitosan is an effective biosilicification template in the presence of phosphate ions because of the multiple hexosamines in its polymer chain [33]. Glycoprotein extracts derived from ESMs also contain abundant hexosamines (N-acetylglucosamine and N-acetylgalatosamine) [3]. This probably explains why the glycoprotein-rich fibre mantle serves as a biocatalyst for polymerisation of silicic acid into silica without using synthetic polyamine analogues. Absence of silica deposition within the collagen-rich ESM fibre core may likewise be rationalised.

As phosphorus is retained within the fibre mantle after biocalcification of the fibre core, we further hypothesise that the ESM may be used as a template for creating hybrid mineralised tissues unseen in Nature by using a combined biocalcification and biosilicification scheme. To test this hypothesis, we first calcified the fibre cores prior to silicifying the fibre mantles without additional tripolyphosphate supplement. This resulted in heavily mineralised ESMs in which the fibre cores were differentially mineralised with apatite crystallites while the fibre mantles were differentially mineralised with silica nanoparticles (Figure 8). STEM-EDX of the mineralised ESMs indicates that calcium was exclusively found in the fibre core and silicon was exclusively located in the fibre mantle (Figure 9). While this represents a proof-of-concept that hybrid mineralised ESM structures may be constructed using a combined biomimetic scheme, the resulting product is too brittle to be handled without breakage.

Figure 8.

Combined biocalcification of the fibre core and biosilicification of the fibre mantle of a MPA pre-treated outer ESM that was phosphorylated with sodium tripolyphosphate. a, Low magnification of the mineralized ESM with calcified fibre cores (C) and silicified fibre mantles (M). E: extrafibre space. Scale bar: 1 μm. b, Higher magnification of the mineral platelet-containing (arrow) calcified fibre core (C) and the silica nanoparticle-containing (arrowhead) silicified fibre mantle (M). Scale bar: 100 nm. c, High magnification of the mineral platelets within the fibre core. Scale bar: 20 nm. d, Selected area electron diffraction of the mineral platelets reveals ring patterns that are characteristic of apatite.

Figure 9.

STEM-EDX of ESMs after combined biocalcification and biosilicification. Elemental maps of the distribution of C, Ca, P, Si and O in the biocalcified and biosilicified ESM. C: Biocalcified fibre core; M: biosilicified fibre mantle; E: extrafibre space. Scale bar: 1 μm.

Nanoindentation of ESMs revealed that their mechanical properties vary with the orientation of the ESM [34]. In that study, the Young’s modulus in the hemispherical direction was 5.50±3.26 MPa, which is in the same order of magnitude as the results obtained from non-mineralised hydrated ESMs in the present study. Moreover, a similar high standard deviation of the mechanical properties was also observed. In its natural form, the ESM is a rather tough membrane but lacks stiffness and hardness due to the absence of intrafibre minerals. This structure-property relation enables the ESM to limit movement of the developing embryo and supporting nutrients to within their spatial confines. A natural ESM that is both tough and stiff is not necessary as protection of the developing embryo from physical injury is efficaciously handled by the calcite-protein component of the eggshell. Nevertheless, by incorporating silica in the fibre mantle, novel ESM-based membranous materials with moderate increases in stiffness may be generated that have potential bioengineering applications. Eggshell membranes with silicified fibre mantles may be milled in liquid nitrogen into micro-leaflets and silanised for incorporation in resin composites as a biomimetic toughening agent [35].

5. Conclusion

In the grand scheme of things, Nature is replete with diversity in her biomineralisation designs. Among such creative solutions is the motif of using amorphous mineral precursors as starting materials and the ability to precisely control where mineralisation is required. Despite many years of research, the exact compositions of the ESM fibre core and mantle have not been fully elucidated due to their highly cross-linked nature and the presence of protein motifs with extensive disulphide cross-links. As commonplace and cryptic as is the ESM, it exemplifies how potentially mineralisable soft tissues can serve as a mineralisation barrier via a proteinaceous coating that surrounds those tissues. Although Nature never requires more than one mineral in her design of a particular matrix-mediated mineralised framework, it is amazing that the ESM has the hidden potential to be mineralised by chemically dissimilar minerals in its different compartmental niches.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R21 DE019213 from NIDCR (PI. Franklin Tay) and the PSRP and ESA awards from the Georgia Health Sciences University. We thank R. Smith (Electron Microscopy Core Unit, Georgia Health Sciences University, USA) for performing electron diffractions, F. Chan (Electron Microscopy Unit, The University of Hong Kong, China) for performing STEM-EDX and electron tomography and M. Burnside for secretarial support.

Appendix. Supporting material

The supporting information associated with this article can be found in the online version.

References

- 1.Carrino DA, Dennis JE, Wu TM, Arias JL, Fernandez MS, Rodriguez JP, et al. The avian eggshell extracellular matrix as a model for biomineralization. Connect Tissue Res. 1996;35:325–8. doi: 10.3109/03008209609029207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nys Y, Gautron J, Garcia-Ruiz JM, Hincke MT. Avian eggshell mineralization: biochemical and functional characterization of matrix proteins. Comptes Rendus Palevol. 2004;3:549–62. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Picard J, Paul-Gardais A, Vedel M. Sulfated glycoproteins form egg shell membranes and hen oviduct. Isolation and characterization of sulfated glycopeptides. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (GAA) 1973;320:427–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arias JL, Nakamura O, Fernández MS, Wu JJ, Knigge P, Eyre DR, et al. Role of type-X collagen on experimental mineralization of eggshell membranes. Connect Tissue Res. 1997;36:21–31. doi: 10.3109/03008209709160211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong M, Hendrix MJC, Von der Mark K, Little C, Stern R. Collagen in the eggshell membranes of the hen. Dev Biol. 1984;104:28–36. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(84)90033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kodali VK, Gannon SA, Paramasivam S, Raje S, Polenova T, Thorpe C. A novel disulfide-rich protein motif from avian eggshell membranes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18187. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiner S. Biomineralization: a structural perspective. J Struct Biol. 2008;163:229–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kröger N, Poulsen N. Diatoms-from cell wall biogenesis to nanotechnology. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:83–107. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu Z, Neoh KG, Kishen A. A biomimetic strategy to form calcium phosphate crystals on type I collagen substrate. Mat Sci Eng C-Mater. 2010;30:822–6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li J, Chiu KL, Kwong FL, Ng DHL, Chan SLI. Conversion of egg shell membrane to inorganic porous CexZr1-xO2 fibrous network. Curr Appl Phys. 2009;9:1438–44. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su H, Song F, Dong Q, Li T, Zhang Z, Zhang D. Bio-inspired synthesis of ZnO polyhedral single crystals under eggshell membrane direction. Appl Phy A. 2010;104:269–74. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y, Liu Y, Ji XB, Banks CE, Song JF. Flower-like agglomerates of hydroxyapatite crystals formed on an egg-shell membrane. Colloid Surface B. 2011;82:490–6. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dey A, Bomans PH, Müller FA, Will J, Frederik PM, de With G, et al. The role of prenucleation clusters in surface-induced calcium phosphate crystallization. Nat Mater. 2010;9:1010–4. doi: 10.1038/nmat2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gower LB. Biomimetic model systems for investigating the amorphous precursor pathway and its role in biomineralization. Chem Rev. 2008;108:4551–627. doi: 10.1021/cr800443h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nudelman F, Pieterse K, George A, Bomans PH, Friedrich H, Brylka LJ, et al. The role of collagen in bone apatite formation in the presence of hydroxyapatite nucleation inhibitors. Nat Mater. 2010;9:1004–9. doi: 10.1038/nmat2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kröger N, Lorenz S, Brunner E, Sumper M. Self-assembly of highly phosphorylated silaffins and their function in biosilica morphogenesis. Science. 2002;298:584–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1076221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sumper M, Brunner E. Learning from diatoms: Nature’s tools for the production of nanostructured silica. Adv Func Mater. 2006;16:7–28. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oliver WC, Pharr GM. An improved technique for determining hardness and elastic modulus using load and displacement sensing indentation experiments. J Mater Res. 1992;7:1564–83. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Li N, Qi YP, Dai L, Bryan TE, Mao J, et al. Intrafibrillar collagen mineralization produced by biomimetic hierarchical nanoapatite assembly. Adv Mater. 2011;23:975–80. doi: 10.1002/adma.201003882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crombie G, Snider R, Faris B, Franzblau C. Lysine-derived cross-links in the egg shell membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;640:365–7. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(81)90560-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yi F, Guo ZX, Zhang LX, Yu J, Li Q. Soluble eggshell membrane protein: preparation, characterization and biocompatibility. Biomaterials. 2004;25:4591–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang T, Chen ML, Hu XW, Wang ZW, Wang JH, Dasgupta PK. Thiolated eggshell membranes sorb and speciate inorganic selenium. Analyst. 2011;136:83–9. doi: 10.1039/c0an00480d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cölfen H. A crystal-clear view. Nat Mater. 2010;9:960–1. doi: 10.1038/nmat2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Y, Kim YK, Dai L, Li N, Khan SO, Pashley DH, et al. Hierarchical and non-hierarchical mineralisation of collagen. Biomaterials. 2011;32:1291–300. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ricard-Blum S, Ruggiero F. The collagen superfamily: from the extracellular matrix to the cell membrane. Pathologie Biologie. 2005;53:430–42. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2004.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schlossmacher U, Wiens M, Schröder HC, Wang X, Jochum KP, Müller WE. Silintaphin-1--interaction with silicatein during structure-guiding bio-silica formation. FEBS J. 2011;278:1145–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brutchey RL, Morse DE. Silicatein and the translation of its molecular mechanism of biosilicification into low temperature nanomaterial synthesis. Chem Rev. 2008;108:4915–34. doi: 10.1021/cr078256b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramanathan R, Campbell JL, Soni SK, Bhargava SK, Bansal V. Cationic amino acids specific biomimetic silicification in ionic liquid: a quest to understand the formation of 3-d structures in diatoms. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belton DJ, Deschaume O, Patwardhan SV, Perry CC. A solution study of silica condensation and speciation with relevance to in vitro investigations of biosilicification. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:9947–55. doi: 10.1021/jp101347q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bronder SR. Stabilizing orthosilicic acid comprising preparation and biological preparation. 5,922,360 United States Patent Office. 1999

- 31.Calomme M, Geusens P, Demeester N, Behets GJ, D’Haese P, Sindambiwe JB, et al. Partial prevention of long-term femoral bone loss in aged ovariectomized rats supplemented with choline-stabilized orthosilicic acid. Calcif Tissue Int. 2006;78:227–32. doi: 10.1007/s00223-005-0288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spector TD, Calomme MR, Anderson SH, Clement G, Bevan L, Demeester N, et al. Choline-stabilized orthosilicic acid supplementation as an adjunct to calcium/vitamin D3 stimulates markers of bone formation in osteopenic females: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leng B, Shao Z, Bomans PH, Brylka LJ, Sommerdijk NA, de With G, et al. Cryogenic electron tomography reveals the template effect of chitosan in biomimetic silicification. Chem Commun (Camb) 2010;46:1703–5. doi: 10.1039/b922670b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Torres FG, Troncoso OP, Piaggio F, Hijar A. Structure-property relationships of a biopolymer network: The eggshell membrane. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:3687–93. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tuan W-H, Yu Y-J, Chin Y-L. From biomimetic concept to engineering reality – a case study on the design of ceramic reinforcement. Adv Eng Mater. 2011;13:351–5. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.