Abstract

This biographical sketch on Georg Hermann von Meyer highlights the interactions in the 1860s that von Meyer, a famous anatomist, had with Karl Culmann, a famous structural engineer and mathematician. The published papers from this interaction caught the attention of Julius Wolff and stimulated his development of the trajectorial hypothesis of bone adaptation—now called “Wolff’s Law.” The corresponding translations are provided: (1) von Meyer’s 1867 paper that highlights the regularity of arched trabecular patterns in various human bones, and his discussions with Culmann about their possible mechanical relevance; and (2) Wolff’s 1869 paper that first mentions the correspondence of stress trajectories in a solid, crane-like structure to the arched trabecular patterns in the proximal human femur. This biographical sketch on Georg Hermann von Meyer corresponds to the historic texts, The Classic: The Architecture of the Trabecular bone (by von Meyer), and The Classic: On the Significance of the Architecture of the Spongy Substance for the Question of Bone Growth. A preliminary publication (by Wolff) available at DOIs 10.1007/s11999-011-2041-5, 10.1007/s11999-011-2042-4.

Georg Hermann von Meyer was born in August 1815 in Frankfurt-on-the-Main, Germany. Information regarding his childhood and preuniversity school years is sparse, and much of the subsequent information is gleaned from the research of Professor B. Rüttimann of Zurich [7]. von Meyer (Fig. 1) completed his premedical studies in Heidelberg, Germany and received his doctorate under the aegis of Johannes Müller in Berlin in 1837, one year after the birth of Julius Wolff. von Meyer’s dissertation, written in Latin, described the structure and function of the muscles of excretory ducts. In 1840, he became a lecturer in physiology and histology in Tübingen, Germany. Four years later, he moved to Switzerland where he became a prosector at the Institute of Anatomy at the University of Zurich. In von Meyer’s time it was not unusual for German scientists to seek work in Switzerland, often for academic freedom and opportunity [1, 2]. By 1856, von Meyer was director of the Institute and held the chair as professor of anatomy. His prominence in research and teaching ultimately earned him the position of dean of the medical faculty and rector of the university. In 1875, he received another great honor when the Senckenberg Society for Natural Science awarded him the Tiedemann Prize; a prize awarded every fourth year to the German scientist who produced the best work in anatomy and physiology. In addition to this honor, the city of Zurich gave him honorary citizenship and he was knighted in the Royal Prussian Order of the Crown.

Fig. 1.

Georg Hermann von Meyer is shown

von Meyer authored many papers for professional and lay audiences. Some of his most important works were the “Textbook on the Physiological Anatomy of the Human Being” [9], “Statics and Mechanics of the Human Skeleton” [11], “Textbook of Human Anatomy” [12], and “The Organs of Speech and their Application in the Formation of Articulate Sounds” [13]. His strong interests in the human skeleton led to his nickname “Bone Meyer,” although his interests in anatomy were much broader than the emphasis implied by this moniker. In 1871, Franziska Tiburtius (one of the earliest females to receive a medical degree in Switzerland) described von Meyer as very dignified, what the English would call “a real gentleman” [6].

A contemporary of von Meyer, also in Zurich, was the soon-to-be famous engineer/mathematician Karl Culmann (1821–1881) (Fig. 2). Culmann, was one of many German scientists at the new Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich or ETH), founded in 1854. In 1855, Culmann became the first professor of civil engineering at this institution [1]. Culmann had trained at the Technological Institute at Karlsruhe, Germany and was experienced in the German construction of railroad structures. He also studied at Metz in France where he became impressed with the French visual tradition of structural analysis. Culmann’s main work, published in 1866, was a massive and scholarly textbook entitled “Graphical Statics” (Die Graphische Statik) [3], which synthesized his German training and taste for calculations and the French idea of visual studies. In this seminal work, he described how the transmission of stresses in structures could be determined with the use of graphical analysis. His approach was later used in the design and engineering of the Eiffel Tower (finished for the 1889 World’s Fair), apparently facilitated by Culmann’s student Maurice Koechlin (1856–1946) who was employed by Eiffel [1]. (Koechlin later gave his original 1884 sketch of the Eiffel Tower to his alma mater, ETH in Zurich.) Illustrated in Culmann’s text are two solid structures showing calculated stress trajectories, which ultimately influenced von Meyer’s ideas about the mechanical relevance of trabecular architecture: (1) a simple cantilevered beam (Fig. 3), and (2) a Fairbairn crane [8, 10].

Fig. 2.

Karl Culmann is shown

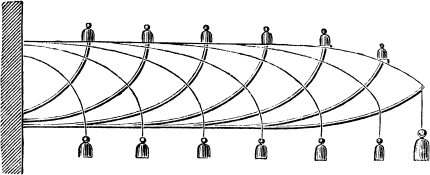

Fig. 3.

Culmann’s (Fig. 107, p. 236) [3] short, cantilevered beam with stress trajectories. This beam illustration is reproduced in several of Wolff’s works [15–17]. (Reproduced from the original.)

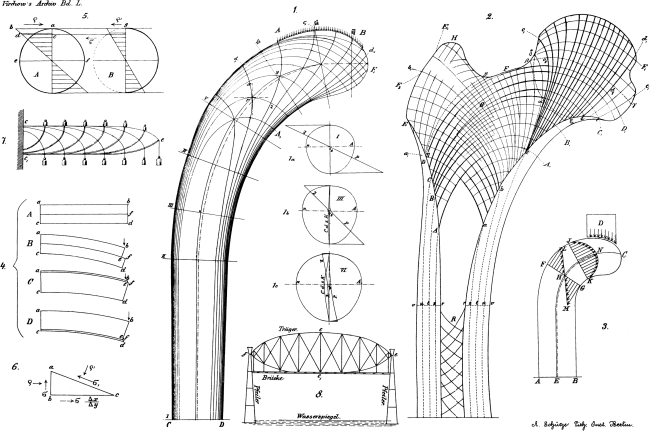

Culmann and von Meyer were both present at the gathering of the Society for Natural Science in Zurich in July 1866. In his 1867 publication, von Meyer highlighted his interactions with Culmann [10]. von Meyer demonstrated arched trabecular patterns in a sagittally sectioned human first metatarsal and calcaneus, and Culmann suggested that the patterns appeared to be aligned along principal stress directions produced by functional loading. Evidently, Culmann first drew the analogy between these trabecular patterns and the stress trajectories of a short, solid, cantilevered beam, as illustrated in his textbook [3] (Fig. 3). von Meyer and Culmann also compared the trabecular architecture in a coronal section of a human proximal femur to the mathematically constructed stress trajectories of a curved, solid, crane-like beam that resembled a human femur (without trochanters) loaded in single-legged stance. This idealized structure, known as Culmann’s ‘crane’ (Fig. 4), resembled an actual Fairbairn crane [8]. von Meyer recognized the various influences on the loading of bone, and not only the external loads: “…besides the static relationships, the arrangement of the cross-section and the mechanical influences of muscle tension and ligament tension must be taken into consideration for a proper interpretation and correct understanding of the platelet systems.”

Fig. 4.

von Meyer’s (1867) [10] composite illustration shows the Culmann ‘crane’ and sections of various human bones with stylized arching trabecular patterns. According to Rüttimann (1992, p. 14), the original figure legend reads: “This graphic gives a modification of the curved crane that Prof. Culmann had designed (see [8]) under his control with the intention of approximately imitating the shape of the upper end of the femur and the transverse section of the neck and presuming the same wide strain as the head of the femur receives from the socket.” (Reproduced from the original.)

Rüttimann [7] quotes Rudolf Fick’s recollection (italics) of the von Meyer–Culmann meeting, with a correction of his own (non-italics):

“He (von Meyer) drew a crane similar to the shape of the upper end of the femur and asked … Culmann to draw in the tension and pressure lines (trajectories) to be calculated by him for this purpose, having already drawn trabeculae that were significant—in his opinion—on another piece of paper. Culmann had one of his pupils, Dr. Hedenauer, make the calculation and drawing and, just imagine, it corresponded with the one of H. Meyer. The above named assistant was not Dr. Hedenauer, but Dr. Andreas Rudolf Harlacher…”

Beginning in 1869, the similarities between these stress trajectories and the arched patterns of trabecular struts in various human bones profoundly influenced the work of Julius Wolff [14]. This led to Wolff’s formulation of the trajectorial hypothesis of trabecular bone architecture, which eventually evolved into common parlance as “Wolff’s Law of the Functional Adaptation of Bone” or “Wolff’s Law” [16, 17].

Wolff was convinced that the similarities between stress trajectories in Culmann’s ‘crane’ and the arched trabecular patterns in the human proximal femur could not be coincidental. He therefore hypothesized “the direction and pattern of loading influences, and/or controls, the pattern of the trabecular framework” [8]—hence the origin of Wolff’s emphasis on ‘mathematical laws’ (ie. that there is a direct mathematical relationship between bone form and skeletal loads).

Notably, the arched trabecular patterns in the von Meyer femur do not always form orthogonal intersections (ie., do not cross at 90°) as they clearly do in the Culmann ‘crane’ (compare these drawings in Fig. 4) [4, 5]. To our knowledge, however, von Meyer, did not mathematically analyze the course of apparent “tension” and “compression” curvilinear trabecular patterns, and did not further rigorously consider the implications of the nonorthogonal intersections that he illustrated in this drawing of a human proximal femur. Recognizing this discrepancy—with what he perceived to be orthogonal trabecular patterns in his own thinly sectioned proximal femora—Wolff admonished von Meyer for not drawing the femoral trabecular patterns “correctly” [14]. In contrast to von Meyer’s femur drawing (Fig. 4), Wolff’s composite illustration of 1870 [15, 18] showed orthogonally intersecting trabecular arches in a diagrammatic drawing of a coronally sectioned human proximal femur (Fig. 5). Wolff’s unwavering depictions of orthogonal trabecular intersections reflected his steadfast view that this was the manifestation of an important biological process that mediates bone development. (Wolff conveniently ignored the fact that many trabeculae do not cross at right angles and usually do not connect to the inner cortex at right angles; scientists are prone to overlooking evidence contrary to their theories.) Unlike Wolff’s comparatively focused passion for studying the concept of bone adaptation occurring in response to mechanical stress, the bulk of von Meyer’s professional career focused on broader aspects of human anatomy and physiology.

Fig. 5.

Wolff’s [15] composite diagram with 8 figures. Wolff obtained the drawing of the ‘crane’ and most of the other structures from Culmann [15, 16]. A translation of the original figure legend can be found in [8]. Fig. 1. Illustration of forces and trajectories that act on the interior of a bone; this is based on the original crane-like structure drawn by students of Professor K. Culmann under his supervision. Fig. 2. Schematic reproduction of human proximal femur. Figs. 3–7 These relate to the explanation of the ‘‘graphical static’’ method. Fig. 8. Schematic illustration of a bridge showing examples of stress-carrying structural members. (Reproduced from the original.)

In 1892, the year of von Meyer’s death, Wolff published his famous treatise “The Law of Bone Transformation” (Das Gesetz der Transformation der Knochen) [16, 17]. In this work, Wolff summarized his observations and built a case for what became a pervasive doctrine, which he acknowledged was seminally influenced by the von Meyer-Culmann interaction in 1867.

References

- 1.Billington DP. The Tower and The Bridge: The New Art of Structural Engineering. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Billington DP. The Art of Structural Design: A Swiss Legacy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Culmann K. Die Graphische Statik. Zurich: Verlag von Meyer & Zeller; 1866. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jang IG, Kim IY. Computational study of Wolff’s law with trabecular architecture in the human proximal femur using topology optimization. J Biomech. 2008;41:2353–2361. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jansen M. On Bone Formation: Its Relation to Tension and Pressure. London, UK: Longmans, Green and Co; 1920. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koch F. Der Anatom Georg Hermann von Meyer 1815–1892. Zurich: Juris Druck & Verlag; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rüttimann B. A noteworthy meeting of the society for nature research in Zurich two important precursors of Julius Wolff: Carl Culmann and Hermann von Meyer. In: Regling G, ed. Wolff’s Law and Connective Tissue Regulation. New York, NY: Walter de Gruyter; 1992:13–22.

- 8.Skedros JG, Baucom SL. Mathematical analysis of trabecular ‘trajectories’ in apparent trajectorial structures: the unfortunate historical emphasis on the human proximal femur. J Theor Biol. 2007;244:15–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer GH. Lehrbuch der physiologischen Anatomie des Menschen. Leipzig: Verlag von Wilhelm Engelmann; 1856. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyer GH. Die Architectur der Spongiosa. Reichert und Du Bois-Reymond’s Archiv. 1867;8:615–628. [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Meyer GH. Die Statik und Mechanik des menschlichen Knochengerüstes. Edited, Leipzig: Verlag von Wilhelm Engelmann; 1873.

- 12.Meyer GH. Lehrbuch der Anatomie des Menschen. Leipzig: Verlag von Wilhelm Engelmann; 1873. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer GH. The Organs of Speech and their Application in the Formation of Articulate Sounds. London: Kegan Paul, Trench & Co.; 1883. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolff J. Ueber die Bedeutung der Architectur der spongiösen Substanz für die Frage vom Knochenwachsthum. Centralblatt fur die medicinischen Wissenschaften. 1869;54:849–851. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolff J. Ueber die innere Architectur der Knochen und ihre Bedeutung für die Frage vom Knochenwachsthum. Virchows Archiv Pathol Anat Physio. 1870;50:389–450. doi: 10.1007/BF01944490. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolff J. Das Gesetz der Transformation der Knochen. Berlin: Verlag von August Hirschwald; 1892. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolff J. The Law of Bone Remodelling. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolff J. The Classic: On the inner architecture of bones and its importance for bone growth. 1870. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:1056–1065. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1239-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]