Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine the association of hormone levels with the occurrence of musculoskeletal pain. Men ages 40 to 79 years were recruited from population registers in 8 European centres. Subjects were asked to complete a postal questionnaire, which enquired about lifestyle and the occurrence of musculoskeletal pain over the past month. Total testosterone (T), oestradiol (E2), luteinising hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) were assayed from a fasting blood sample. The association between pain status and hormone levels was assessed using multinomial logistic regression with results expressed as relative risk ratios (RRR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). A total of 3206 men had complete data on pain status. Of these, 8.7% reported chronic widespread pain (CWP), whereas 50% had some pain although not CWP and were classified as having some pain. T and E2 were not associated with musculoskeletal pain, whereas significant differences in LH and FSH levels were found between pain groups. After adjustment for age and other possible confounders, the association between pain status and both LH and FSH persisted. Compared with those in the lowest tertile of LH, those in the highest tertile were more likely to report some pain (vs no pain, RRR = 1.28; 95% CI 1.09 to 1.50) and also CWP (vs no pain, RRR = 1.51; 95% CI 1.10 to 2.07). Similar results were found for FSH. Gonadotrophins, but not sex steroid hormone levels, are associated with musculoskeletal pain in men.

Higher levels of gonadotrophins but not androgens were significantly associated with musculoskeletal pain in men. Alterations in hypothalamic–pituitary–testicular feedback mechanisms may play a role in the onset of chronic widespread pain.

Keywords: Musculoskeletal pain, Reproductive hormones, American College of Rheumatology, European Male Ageing Study, Epidemiology

1. Introduction

Fibromyalgia, a noninflammatory rheumatic disorder characterised by chronic widespread pain (CWP), is one of the most common reasons for consultation at rheumatology clinics in Western Europe and North America [29]. Extensive investigations over the past 20 years have begun to uncover the aetiology and biological processes involved in the development of these symptoms.

A number of studies have explored the relationship between musculoskeletal pain and various biomarkers in an attempt to explain the pathophysiological processes underlying pain development. For example, a relationship has been reported between the onset of CWP and altered functioning of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis [18]. Other studies [4,19] have explored the relationship between the growth hormone insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) axes and pain. Recent reports have also shown that CWP is associated with low levels of vitamin D [9,17,23].

The role of reproductive hormones is less clearly defined. A recent review outlined the potential role of sex hormones in relation to the occurrence of musculoskeletal pain among men and women [5] and highlighted that fibromyalgia most often develops during the menopausal transition. Such observations have led to suggestions that declines in female sex hormones, mainly oestrogens, may be linked to the occurrence of pain among women. Similarities also have been drawn in men in terms of testosterone (T) having a putative protective role against the development of musculoskeletal pain [5].

Experiments in animal models have explored the relationship between T and pain threshold [22], suggesting that low T could be associated with decreased pain thresholds and increased pain sensitivity. However, these relationships remain controversial in humans, and the mechanisms by which T and other reproductive hormones affect pain threshold and sensitivity remain unknown.

Few studies have looked specifically at the role of reproductive hormones on the occurrence and severity of musculoskeletal pain. Further, most data derive from women [15], reflecting their higher prevalence of CWP and the distinct hormonal changes associated with the menopause. It has also been suggested that the process of pubertal development may initiate biological changes that predispose women in particular to experience symptoms, including pain [13].

No current data exist looking at the association between the occurrence of musculoskeletal pain and levels of sex steroid hormones, gonadotrophins, and hypogonadism in men. Hypogonadism, or androgen deficiency, adversely impacts functioning of multiple organ systems [28]. Patients with classical hypogonadism are routinely classified into those with secondary hypogonadism (hypothalamic–pituitary failure) with low T and low or normal gonadotrophins, or primary hypogonadism (testicular failure) characterised by low T and elevated gonadotrophins. In addition, men with normal T but elevated gonadotrophins form a distinct subgroup, which may be characterised as subclinical hypogonadism [26]. The relationship between these hypogonadal states and musculoskeletal pain is not known.

The European Male Aging Study is a population-based study of aging in middle-aged and older men [12]. We used data from this study to explore the association between sex steroid hormones, luteinising hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and the occurrence of musculoskeletal pain.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

A total of 3369 men aged 40 to 79 years were recruited for participation in the European Male Aging Study (EMAS) from population registers in 8 European centres: Manchester (UK), Leuven (Belgium), Malmö (Sweden), Tartu (Estonia), Lodz (Poland), Szeged (Hungary), Florence (Italy), and Santiago de Compostela (Spain). All subjects were invited to participate by letter of invitation, which included a short questionnaire (postal questionnaire). Those who agreed to take part attended a local clinic/facility for detailed assessments including an interviewer-assisted questionnaire, height, weight and physical function measurements and fasting blood sampling. Ethical approval for the study was obtained in accordance with local institutional requirements in each centre, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.2. Assessments

The postal questionnaire included questions about smoking and the frequency of alcohol consumption (days per week). There were also questions about the occurrence of pain (see below) and self-reported comorbid conditions: hypertension, bronchitis, asthma, peptic ulcer, epilepsy, diabetes mellitus, cancers, and cardiac, liver, kidney, prostate, and thyroid disorders. A more detailed assessment, undertaken when the patient subsequently attended the clinic, included the Beck Depression Inventory to measure the presence and severity of depression using a 21-item scale with each item scored between 0 and 3 with a total score between 0 and 63 [3]. Higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms. Physical performance was assessed using the Reuben’s Physical Performance Test (PPT) [24], a direct observational instrument that assesses multiple dimensions of physical function, as well as the 50-foot walk test (PPT walk), which requires subjects, on the command “go,” to walk 50 feet. The time taken to complete the task was recorded. Higher scores indicate slower walking as a proxy for lower extremity physical performance.

2.3. Assessment of pain status

CWP was classified using the definition in the American College of Rheumatology criteria for fibromyalgia [30]. These criteria require pain, lasting at least 3 months, distributed above and below the waist, on the right and left sides of the body and in the axial skeleton. All subjects who reported pain that did not satisfy these criteria were classified as having other pain. This instrument has been frequently used in population surveys, and its construct validity has been demonstrated [10,16]. All subjects were asked, “In the past month, have you had any pain which has lasted for one day or more?” Subjects who responded negatively were classified as having no pain. If subjects answered positively, they were asked to indicate the site(s) of pain on a body manikin with views of the front, back, and both sides. To assess for chronicity of pain, subjects were asked whether they had been aware of the pain for 3 months or more.

2.4. Sex steroid and gonadotropin hormone assessment

A single fasting venous blood sample was obtained before 10:00 am. Measurements of total T and oestradiol (E2) were carried out by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry [11]. Dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate, sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), LH, and FSH were assayed by the Modular E170 platform electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) as described elsewhere [32]. Free T and E2 levels were derived from total hormone, SHBG, and albumin concentrations [27].

2.5. Statistical analysis

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as body weight (kg) divided by the square of height (m2). Frequency of alcohol consumption was categorised as none (no days per week), infrequent (1 to 4 days per week) and frequent (⩾5 days per week). Analysis of variance or Kruskall–Wallis (for nonnormal continuous variables) tests were used to determine whether there were differences in the pain groups (CWP/some pain/no pain) for hormone levels and other continuous variables; χ2 tests were used for categorical variables. Multinomial logistic regression was used to assess the relationship between pain status (dependent variable) and the various sex steroid and gonadotrophin hormones. In these analyses, hormone levels were initially included as continuous variables. Subjects were also categorised into tertiles based on the pain status distribution of individual sex steroid and gonadotrophin levels (with the lowest or highest tertile as referent). This categorical approach allowed for an examination of any potential nonlinear relationships between hormone levels and musculoskeletal pain. Analyses were performed after adjustment for age and after subsequent adjustment for a range of possible confounders including smoking, alcohol intake, BMI, self-reported morbidity (one or more vs none), PPT walk time, Beck Depression Inventory, and centre. In the multinomial logistic regression analyses, the category outcome of no pain was used as the base comparison group.

We also explored whether there was any combined effect of LH and FSH on pain status. Gonadotrophin status was constructed as a 4-group variable using LH and FSH tertiles. The 4 groups were: high gonadotrophin (highest tertiles of both LH and FSH), normal/low gonadotrophin (both LH and FSH below their respective highest tertile levels), and 2 discordant groups (high LH and normal/low FSH) and (normal/low LH and high FSH). The association between these 4 gonadotrophin groups and pain status was explored in the same fashion as above.

Additional analyses were carried out using a 4-category variable of functional gonadal status (eugonadal, primary, secondary, and compensated hypogonadism) constructed using 2 thresholds as described previously [26], ie, a T level of 10.5 nmol/L, this T cut point of 10.5 nmol/L corresponded to the median value of the T thresholds recently published by our group [31], whereas the LH threshold of 9.4 U/L corresponds to the 97.5th percentile (the upper limit of normal) value in the youngest group (40 to 44 years) in our analysis cohort. The 4 categories were: eugonadal (T ⩾ 10.5 nmol/L and LH ⩽ 9.4 U/L), secondary hypogonadism (T < 10.5 nmol/L and LH ⩽ 9.4 U/L), primary hypogonadism (T < 10.5 nmol/L and LH > 9.4 U/L), and compensated hypogonadism (T ⩾ 10.5 nmol/L and LH > 9.4). Similar groups were also created using the 97.5th percentile of FSH from the youngest age group (age 40 to 44 years), this FSH level was 15.11 U/L. The relationships between gonadal status (independent variable) and pain status (outcome) was assessed using the same modeling strategy as above.

Robust standard errors were considered to take into account the hierarchy of the study design (individuals nested within centres). Results are expressed as relative risk ratios (RRR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the multinomial logistic regression models. All statistical analyses were conducted using Intercooled STATA version 9.2.

3. Results

3.1. Subject characteristics

Of the 3369 participants, 3206 (95%) provided full data on pain status and were available for the current analysis. Of these 1314 (41%) reported no pain in the past month, 278 (9%) reported pain that satisfied the American College of Rheumatology (ACM) criteria for CWP, whereas 1614 (50%) were classified as having other pain, ie, men who had some pain although not CWP. The baseline characteristics of the analysis sample are shown in Table 1. The mean (SD) age was 59.9 (11.0) years, and mean (SD) BMI was 27.7 (4.1) kg/m2. Just over one fifth were current smokers, and a similar proportion (23%) consumed alcohol on 5 or more days per week. Over 50% of the men reported 1 or more morbid conditions. Pain status was independent of any medications likely to affect hypothalamic–pituitary–testicular function (anabolic-androgenic steroids, Dehydroepiandrosteron (DHEA), anti-androgens, gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonists, and psycholeptic agents), or clearance of sex steroids (anticonvulsants) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Subject characteristics: all subjects, and by pain status.

| Analysis sample N = 3206 | No pain 1314 (41%) | Some pain 1614 (50%) | CWP 278 (9%) | P value∗ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | |||||

| Age at baseline (years) | 59.86 (11.03) | 59.84 (10.89) | 59.87 (11.16) | 59.84 (10.94) | .99 |

| Height (m) | 173.64 (7.35) | 173.61 (7.40) | 173.71 (7.36) | 173.33 (7.14) | .72 |

| Weight (kg) | 83.48 (13.96) | 82.18 (12.92) | 84.08 (14.26) | 86.14 (16.28) | <.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.67 (4.10) | 27.25 (3.84) | 27.85 (4.20) | 28.59 (4.46) | <.001 |

| Total testosterone (nmol/L) | 16.49 (6.03) | 16.65 (6.02) | 16.34 (6.03) | 16.57 (6.12) | .36 |

| Free testosterone (pmol/L) | 290.59 (88.77) | 292.56 (88.92) | 290.11 (88.77) | 284.00 (88.04) | .33 |

| Median interquartile range)† | |||||

| Slow walking speed (seconds) | 13.17 (3.00) | 12.93 (2.80) | 13.20 (3.03) | 13.80 (3.14) | <.001 |

| Beck depression inventory | 5.00 (8.00) | 4.00 (7.00) | 6.00 (7.00) | 8.00 (11.00) | <.001 |

| LH (U/L) | 5.23 (3.38) | 5.03 (3.05) | 5.32 (3.53) | 5.77 (3.84) | .001 |

| FSH (U/L) | 6.04 (5.32) | 5.86 (5.00) | 6.14 (5.37) | 6.71 (5.48) | .003 |

| DHEAS (μmol/L) | 4.00 (3.60) | 4.00 (3.70) | 4.00 (3.65) | 4.10 (3.30) | .57 |

| SHBG (nmol/L) | 39.10 (22.90) | 39.85 (22.50) | 38.20 (22.90) | 40.60 (24.20) | .04 |

| E2 (pmol/L) | 70.08 (30.51) | 69.97 (27.97) | 70.19 (32.16) | 70.04 (33.11) | .64 |

| Free E2 (pmol/L) | 1.20 (0.52) | 1.19 (0.51) | 1.21 (0.54) | 1.19 (0.53) | .61 |

| Count (%) | |||||

| Drugs related to hypogonadism | 139 (4.34) | 53 (4.03) | 68 (4.21) | 18 (6.47) | .18 |

| Number of comorbidities (1 or more) | 1634 (51.71) | 587 (45.26) | 876 (55.16) | 171 (62.18) | <.001 |

| Smoking status (current) | 667 (20.96) | 251 (19.25) | 344 (21.49) | 72 (25.99) | <.03 |

| Alcohol intake (⩾5 days/week) | 739 (23.17) | 305 (23.34) | 396 (24.67) | 38 (13.72) | <.001 |

Morbidities included heart conditions, high blood pressure, stroke, cancer, bronchitis, asthma, peptic ulcer, epilepsy, diabetes, and liver, kidney, and prostate diseases.

∗P value for (continuous variables): ANOVA or †Kruskall–Wallis test. ∗P value for categorical variables χ2 test of independence.

LH = luteinising hormone, FSH = follicle-stimulating hormone, SHBG = sex hormone-binding globulin, DHEAS = dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate, E2 = oestradiol, SD = standard deviation.

3.2. Relationship between pain status and hormone variables

Hormonal distributions by pain status are shown in Table 1. Significant differences between levels of gonadotrophins by pain group were observed (P < .01, Kruskall–Wallis test) for both LH and FSH. There were no significant differences between pain groups in total and free T levels.

Table 2 shows data concerning the association between pain status and sex steroid, and gonadotrophin levels. Model I shows the age-adjusted RRRs, and model II the RRRs in the fully adjusted model.

Table 2.

Multinomial logistic regression models testing associations between hormones (continuous and tertiles) and musculoskeletal pain.

| RRR (95% CI) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model I |

Model II |

||||

| Some pain | CWP | Some pain | CWP | ||

| Total T (nmol/L) | |||||

| Continuous | 0.99 (0.98 to 1.00) | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.02) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.04) | |

| Tertiles | Highest | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Middle | 1.03 (0.86 to 1.24) | 1.17 (0.85 to 1.60) | 0.99 (0.86 to 1.14) | 1.12 (0.64 to 1.96) | |

| Lowest | 1.19 (0.99 to 1.42) | 1.14 (0.82 to 1.58) | 1.02 (0.86 to 1.21) | 0.88 (0.59 to 1.31) | |

| Free T (pmol/L) | |||||

| Continuous | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | |

| Tertiles | Highest | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Middle | 1.08 (0.90 to 1.30) | 1.15 (0.82 to 1.59) | 1.04 (0.86 to 1.26) | 1.04 (0.75 to 1.44) | |

| Lowest | 1.07 (0.89 to 1.30) | 1.28 (0.91 to 1.79) | 0.89 (0.64 to 1.23) | 0.92 (0.63 to 1.34) | |

| LH (U/L) | |||||

| Continuous | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.05)⁎⁎ | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.06) | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.05)⁎ | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.05) | |

| Tertiles | Highest | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Middle | 1.04 (0.87 to 1.24) | 0.91 (0.65 to 1.27) | 1.07 (0.87 to 1.31) | 0.92 (0.57 to 1.50) | |

| Lowest | 1.29 (1.07 to 1.55)⁎⁎ | 1.66 (1.21 to 2.29)⁎⁎ | 1.28 (1.09 to 1.50)⁎⁎ | 1.51 (1.10 to 2.07)⁎ | |

| FSH (U/L) | |||||

| Continuous | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.02)⁎⁎ | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.03) | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.02) | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.02) | |

| Tertiles | Highest | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Middle | 1.17 (0.97 to 1.40) | 1.25 (0.90 to 1.75) | 1.13 (0.84 to 1.52) | 1.14 (0.77 to 1.69) | |

| Lowest | 1.25 (1.03 to 1.51)⁎ | 1.69 (1.21 to 2.37)⁎⁎ | 1.23 (0.99 to 1.52) | 1.47 (1.15 to 1.87)⁎⁎ | |

| DHEAS (μmol/L) | |||||

| Continuous | 0.99 (0.96 to 1.02) | 0.99 (0.94 to 1.05) | 0.99 (0.96 to 1.02) | 1.01 (0.97 to 1.05) | |

| Tertiles | Highest | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Middle | 1.06 (0.87 to 1.27) | 1.04 (0.75 to 1.45) | 1.09 (0.87 to 1.36) | 1.00 (0.73 to 1.35) | |

| Lowest | 1.12 (0.91 to 1.38) | 0.97 (0.67 to 1.41) | 1.13 (0.88 to 1.44) | 0.81 (0.59 to 1.11) | |

| SHBG (nmol/L) | |||||

| Continuous | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.01) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.01) | |

| Tertiles | Highest | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Middle | 0.80 (0.67 to 0.96)⁎ | 1.09 (0.79 to 1.52) | 0.87 (0.73 to 1.03) | 1.32 (0.87 to 2.01) | |

| Lowest | 0.85 (0.70 to 1.03) | 1.20 (0.85 to 1.70) | 0.93 (0.70 to 1.23) | 1.32 (0.88 to 1.98) | |

| E2 (pmol/L) | |||||

| Continuous | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.01) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.01) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) | |

| Tertiles | Highest | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Middle | 0.87 (0.73 to 1.04) | 0.81 (0.58 to 1.12) | 0.87 (0.69 to 1.10) | 0.79 (0.54 to 1.17) | |

| Lowest | 1.05 (0.88 to 1.26) | 1.17 (0.86 to 1.61) | 0.99 (0.76 to 1.28) | 1.04 (0.71 to 1.51) | |

| Free E2 (pmol/L) | |||||

| Continuous | 1.12 (0.95 to 1.32) | 1.00 (0.74 to 1.36) | 1.03 (0.77 to 1.38) | 0.91 (0.63 to 1.31) | |

| Tertiles | Highest | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Middle | 1.03 (0.86 to 1.24) | 0.90 (0.65 to 1.25) | 1.06 (0.88 to 1.28) | 0.91 (0.57 to 1.45) | |

| Lowest | 1.04 (0.87 to 1.25) | 1.08 (0.79 to 1.48) | 0.99 (0.73 to 1.33) | 1.00 (0.59 to 1.69) | |

Model (I) adjusted for age. Model (II) adjusted for age, smoking status, alcohol intake, body mass index, morbidities, Reuben’s Physical Performance Test walk time, depression, and centre.

Separate model for each hormone. Base category for the outcome was no pain. For hormones as continuous variables, RRRs correspond to a 1-unit increases in the relevant hormone.

RRR = relative risk ratios, CI = confidence interval, LH = luteinising hormone, FSH = follicle-stimulating hormone, SHBG = sex hormone-binding globulin, DHEAS = dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate, E2 = oestradiol, CWP = chronic widespread pain.

P < .05.

P < .01.

In model II, high LH levels were associated with the presence of musculoskeletal pain: the RRRs may be interpreted as “the risk of being in the some pain group versus being in the no pain group was 1.28 (95% CI 1.09 to 1.50) times as great for men in the highest LH tertile as in those in the lowest LH tertile.” The risk of being in the CWP group versus being in the no pain group was 1.51 (95% CI 1.10 to 2.07) times as great for men in the highest LH tertile as for those in the lowest LH tertile (Table 2). Looking at the gonadotrophins (LH and FSH) as continuous variables, there was an association mainly with some pain, although with CWP the relationships were at the borderline of statistical significance, possibly due to a lack of statistical power (Table 2).

Similarly, those in the highest tertile of FSH were more likely to report CWP (vs no pain, RRR = 1.47; 95% CI 1.15 to 1.87) (model II, Table 2). There were no other significant associations between pain status and reproductive hormones (SHBG) in the final models (model II).

Table 3 shows the joint effect of LH and FSH on reporting pain. In total, 10.7% of subjects had normal/low LH and high FSH, 10.6% had high LH and normal/low FSH, 22.5% had high LH and high FSH, and the remaining 56.1% had normal/low LH and normal/low FSH.

Table 3.

Multinomial logistic regression models testing joint association between high, normal/low FSH and LH levels and musculoskeletal pain.

| RRR (95% CI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model I |

Model II |

|||

| Some pain | CWP | Some pain | CWP | |

| Combination of LH and FSH levels | ||||

| Normal/low LH and normal/low FSH | ||||

| n = 1788 (56.14%) | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Normal/low LH and high FSH n = 342 (10.74%) | 0.95 (0.74 to 1.22) | 1.13 (0.72 to 1.76) | 0.99 (0.86 to 1.15) | 1.06 (0.76 to 1.47) |

| High LH and normal/low FSH n = 338 (10.61%) | 1.16 (0.90 to 1.48) | 1.53 (1.01 to 2.43)⁎ | 1.14 (0.87 to 1.49) | 1.39 (0.85 to 2.30) |

| High LH and high FSH n = 717 (22.51%) | 1.31 (1.07 to 1.59)⁎⁎ | 1.93 (1.39 to 2.69)⁎⁎⁎ | 1.29 (1.06 to 1.56)⁎ | 1.69 (1.36 to 2.10)⁎⁎⁎ |

Low corresponds to LH/FSH levels below the highest tertiles, high means in the highest tertiles.

Model I: adjusted for age. Model II: adjusted for age, smoking status, alcohol intake, body mass index, morbidities, Reuben’s Physical Performance Test walk time, depression, and centre. Base category for the outcome is no pain.

RRR = relative risk ratios, CI = confidence interval, LH = luteinising hormone, FSH = follicle-stimulating hormone, CWP = chronic widespread pain.

P < .05.

P < .01.

P < .001.

In the fully adjusted models, only men in the high LH and FSH group were more likely to report some pain (vs no pain) (RRR = 1.29; 95% CI 1.06 to 1.56), and (vs. no pain) CWP (RRR = 1.69; 95% CI 1.36 to 2.10). No associations were observed in the other groups.

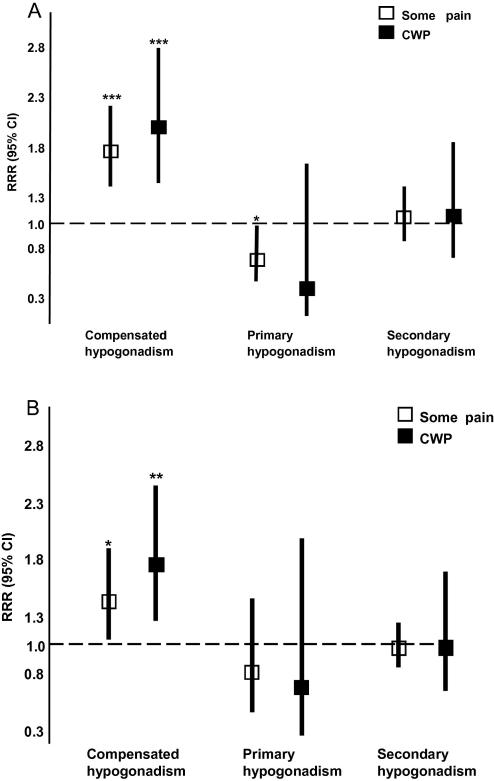

3.3. Pain status and gonadal status

As outlined above, men were categorised into 1 of 4 groups based on their level of total T and gonadotrophin hormone (either LH or FSH). Compared with those in the eugonadal group, those in the compensated group were more likely to report some pain (vs no pain) (RRR = 1.71; 95% CI 1.36 to 2.15) and also CWP (vs. no pain) (RRR = 1.95; 95% CI 1.39 to 2.73) (Fig. 1A). A weak negative association was found with primary hypogonadism (Fig. 1A). Broadly similar findings were observed when the 4 groups were defined on the basis of their FSH, rather than LH, level (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Results of multinomial logistic regression exploring the association between hypogonadal status and musculoskeletal pain. (A) Combination of total T and LH. (B) Combination of total T and FSH. Multinomial logistic regression models: adjusted for age, smoking status, alcohol intake, body mass index, morbidities, Physical Performance Test walk time, depression, and centre. The base category for the outcome is no pain. The RRR indicates the likelihood of being classified in one of the outcome categories, some pain or CWP compared with the base category no pain. They may be interpreted by saying, for example, the risk of being in the some pain group versus being in the no pain group was 1.95 (P < .001) times greater for men in the compensated hypogonadism group as for eugonadal men (A). CI = confidence interval; CWP = chronic widespread pain; LH = luteinising hormone; FSH = follicle-stimulating hormone; RRR = relative risk ratios; T = testosterone. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001.

Additionally, we repeated the same analyses after excluding 14 men who reported opioid use (10 of these 14 men were classified as some pain and the remaining 4 reported CWP), the results were similar to those presented here (data not shown).

4. Discussion

We report here the findings of the first population-based study on the associations between male reproductive hormones and musculoskeletal pain. We found significant associations between higher levels of gonadotrophins and musculoskeletal pain after adjustment for potential health and lifestyle confounders. There was, however, no association between musculoskeletal pain and sex steroid levels.

Studies in women [1,6,7,15,21] provide somewhat conflicting data concerning the relationship between reproductive hormone levels and musculoskeletal pain. In a population-based study [15] exploring the relationship between hormones and CWP in women, no clear associations were observed. Results from another case control study [21] suggested that fibromyalgia was unlikely to be attributed to any significant hormonal disruptions. In contrast to these observations, however, higher gonadotrophin levels were reported among fibromyalgia patients compared with healthy controls [7]. Our data, based on the occurrence of musculoskeletal pain, support these findings and extend them to men.

A study [8] involving 57 women followed up during their menopausal transition found an association between musculoskeletal pain and E2. In EMAS, we found no relationship between E2 and pain status among middle-aged and older men. A possible explanation for the discrepancy is that higher levels of oestrogens in women may predispose them to greater pain than men [5].

What are the possible mechanism underlying our observations? The absence of any association between androgens and pain status observed in this cohort may suggest that the age-related decline of T in men may not have an important role in the occurrence of pain, in contrast with the strong association between changes in oestrogen levels and musculoskeletal pain in women. However, disruptions in testicular function (elevated gonadotrophins) appear to be related to the presence of musculoskeletal pain. It is possible that high gonadotrophin levels among men with CWP may be considered as a biomarker for a previous T decline within the normal physiological range (10 to 30 nmol/L), thus indicating a readjustment of the pituitary–testicular feedback set point that compensates for defective T feedback at the hypothalamic–pituitary level [14], or as genuine androgen deficiency with respect to the man’s individual normal level. If so, it might be expected that there would be an association with T that was not the case here. Alternatively, the onset of CWP as a marker of poor health could result in an increase in gonadotrophin levels as an early sign of imminent testicular failure. A further possibility is that alterations in the hormonal feedback mechanisms controlled by the hypothalamus may play a role in the symptomatology of fibromyalgia [20]. Interestingly, the LH receptor has been localised not only in the reproductive organs but also as a functional protein within the central nervous system, including regions of the brain involved in sensory functions [2]. It is biologically plausible, therefore, that LH may have either direct effects within the central nervous system or indirect effects via regulation of neurosteroid production [2], although this would not explain the observed association of FSH with pain status. However, these 2 hormones are jointly regulated by the hypothalamic gonadotrophin-releasing hormone and their levels usually change in parallel. Prospective data are warranted to confirm these findings and to help determine the temporal nature of the relationships.

Our study has a number of strengths: it was a large population-based study that used standardised, well-validated instruments to assess pain and putative confounders. The study also used the state-of-the-art mass spectrometry-based method (gas chromatography–mass spectrometry) for measuring serum T levels, as recommended recently by the Endocrine Society’s Positional Statement [25]. There are, however, some methodological limitations that need to be considered in interpreting the findings. It is possible that the prevalence of pain among those who participated may have differed from that in those who declined to participate, and some caution is needed in interpreting the data. Factors influencing participation are, however, unlikely to have influenced the results of the risk factor analysis, which was based on an internal comparison of those who participated. Given the cross-sectional nature of the study data, it is not possible to determine the temporal nature of the relationship between pain and reproductive hormone status for which future prospective data of the EMAS cohort are needed. Finally, our results were derived from a population sample of middle-aged and older European men, and should be extrapolated beyond this group with caution.

In summary, gonadotrophins, but not sex steroid hormone levels, are associated with musculoskeletal pain in men. Further prospective data are required to confirm these findings and to determine the temporal nature of the observed associations.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted with the ethical approval of the 8 European centres in accordance with local institutional requirements in each centre, and written informed consent was obtained.

Conflict of interest statement

The final manuscript has been seen and approved by all of the authors, who have given the necessary attention to ensure the integrity of the work. The authors have no financial or conflict of interest to disclose concerning this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The European Male Aging Study (EMAS) is funded by the Commission of the European Communities Fifth Framework Programme “Quality of Life and Management of Living Resources” Grant QLK6-CT-2001-00258.

The authors thank the men who participated in the 8 countries, the research/nursing staff in the eight centres: C. Pott, Manchester, E. Wouters, Leuven, M. Nilsson, Malmö, M. del Mar Fernandez, Santiago de Compostela, M. Jedrzejowska, Lodz, H.-M. Tabo, Tartu, A. Heredi, Szeged, for their meticulous data collection and C. Moseley, Manchester, for data entry and project coordination. Dr. S. Boonen is a senior clinical investigator of the Fund for Scientific Research, Flanders, Belgium (F.W.O. – Vlaanderen), and holder of the Novartis Leuven University Chair in Gerontology and Geriatrics. Dr. Vanderschueren is a senior clinical investigator supported by the Clinical Research Fund of the University Hospitals Leuven, Belgium. Support from the Arthritis Research UK and the NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre is acknowledged.

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

References

- 1.Akkus S., Delibas N., Tamer M.N. Do sex hormones play a role in fibromyalgia? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:1161–1163. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.10.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apaja P.M., Harju K.T., Aatsinki J.T., Petaja-Repo U.E., Rajaniemi H.J. Identification and structural characterization of the neuronal luteinizing hormone receptor associated with sensory systems. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1899–1906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311395200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck A.T., Ward C.H., Mendelson M., Mock J., Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett R.M., Cook D.M., Clark S.R., Burckhardt C.S., Campbell S.M. Hypothalamic–pituitary–insulin-like growth factor-I axis dysfunction in patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:1384–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cairns B.E., Gazerani P. Sex-related differences in pain. Maturitas. 2009;63:292–296. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dessein P.H., Shipton E.A., Joffe B.I., Hadebe D.P., Stanwix A.E., Van der Merwe B.A. Hyposecretion of adrenal androgens and the relation of serum adrenal steroids, serotonin and insulin-like growth factor-1 to clinical features in women with fibromyalgia. Pain. 1999;83:313–319. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El Maghraoui A., Tellal S., Achemlal L., Nouijai A., Ghazi M., Mounach A., Bezza A., El Derouiche M. Bone turnover and hormonal perturbations in patients with fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006;24:428–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finset A., Øverlie I., Holte A. Musculo-skeletal pain, psychological distress, and hormones during the menopausal transition. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:49–64. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huisman A.M., White K.P., Algra A., Harth M., Vieth R., Jacobs J.W., Bijlsma J.W., Bell D.A. Vitamin D levels in women with systemic lupus erythematosus and fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:2535–2539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunt I.M., Silman A.J., Benjamin S., McBeth J., Macfarlane G.J. The prevalence and associated features of chronic widespread pain in the community using the ‘Manchester’ definition of chronic widespread pain. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38:275–279. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Labrie F., Belanger A., Belanger P., Berube R., Martel C., Cusan L., Gomez J., Candas B., Castiel I., Chaussade V., Deloche C., Leclaire J. Androgen glucuronides, instead of testosterone, as the new markers of androgenic activity in women. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;99:182–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee D.M., O’Neill T.W., Pye S.R., Silman A.J., Finn J.D., Pendleton N., Tajar A., Bartfai G., Casanueva F., Forti G., Giwercman A., Huhtaniemi I.T., Kula K., Punab M., Boonen S., Vanderschueren D., Wu F.C. The European Male Ageing Study (EMAS): design, methods and recruitment. Int J Androl. 2009;32:11–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2008.00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LeResche L., Mancl L.A., Drangsholt M.T., Saunders K., Korff M.V. Relationship of pain and symptoms to pubertal development in adolescents. Pain. 2005;118:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu P.Y., Pincus S.M., Takahashi P.Y., Roebuck P.D., Iranmanesh A., Keenan D.M., Veldhuis J.D. Aging attenuates both the regularity and joint synchrony of LH and testosterone secretion in normal men: analyses via a model of graded GnRH receptor blockade. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290:E34–E41. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00227.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macfarlane T.V., Blinkhorn A., Worthington H.V., Davies R.M., Macfarlane G.J. Sex hormonal factors and chronic widespread pain: a population study among women. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002;41:454–457. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.4.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McBeth J., Macfarlane G.J., Benjamin S., Silman A.J. Features of somatization predict the onset of chronic widespread pain: results of a large population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:940–946. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200104)44:4<940::AID-ANR151>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McBeth J., Pye S.R., O’Neill T.W., Macfarlane G.J., Tajar A., Bartfai G., Boonen S., Bouillon R., Casanueva F., Finn J.D., Forti G., Giwercman A., Han T.S., Huhtaniemi I.T., Kula K., Lean M.E., Pendleton N., Punab M., Silman A.J., Vanderschueren D., Wu F.C. Musculoskeletal pain is associated with very low levels of vitamin D in men: results from the European Male Ageing Study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1448–1452. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.116053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McBeth J., Silman A.J., Gupta A., Chiu Y.H., Ray D., Morriss R., Dickens C., King Y., Macfarlane G.J. Moderation of psychosocial risk factors through dysfunction of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal stress axis in the onset of chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain: findings of a population-based prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:360–371. doi: 10.1002/art.22336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McBeth J., Tajar A., O’Neill T.W., Macfarlane G.J., Pye S.R., Bartfai G., Boonen S., Bouillon R., Casanueva F., Finn J.D., Forti G., Giwercman A., Han T.S., Huhtaniemi I.T., Kula K., Lean M.E., Pendleton N., Punab M., Silman A.J., Vanderschueren D., Wu F.C. Perturbed insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and IGF binding protein-3 are not associated with chronic widespread pain in men: results from the European Male Ageing Study. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:2523–2530. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neeck G. Neuroendocrine and hormonal perturbations and relations to the serotonergic system in fibromyalgia patients. Scand J Rheumatol Suppl. 2000;113:8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okifuji A., Turk D.C. Sex hormones and pain in regularly menstruating women with fibromyalgia syndrome. J Pain. 2006;7:851–859. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pednekar J.R., Mulgaonker V.K. Role of testosterone on pain threshold in rats. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1995;39:423–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plotnikoff G.A., Quigley J.M. Prevalence of severe hypovitaminosis D in patients with persistent, nonspecific musculoskeletal pain. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:1463–1470. doi: 10.4065/78.12.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reuben D.B., Siu A.L. An objective measure of physical function of elderly outpatients. The Physical Performance Test. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38:1105–1112. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosner W., Auchus R.J., Azziz R., Sluss P.M., Raff H. Position statement: utility, limitations, and pitfalls in measuring testosterone: an Endocrine Society position statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:405–413. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tajar A., Forti G., O’Neill T.W., Lee D.M., Silman A.J., Finn J.D., Bartfai G., Boonen S., Casanueva F.F., Giwercman A., Han T.S., Kula K., Labrie F., Lean M.E., Pendleton N., Punab M., Vanderschueren D., Huhtaniemi I.T., Wu F.C. Characteristics of secondary, primary, and compensated hypogonadism in aging men: evidence from the European Male Ageing Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:1810–1818. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vermeulen A., Verdonck L., Kaufman J.M. A critical evaluation of simple methods for the estimation of free testosterone in serum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:3666–3672. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.10.6079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang C., Nieschlag E., Swerdloff R., Behre H.M., Hellstrom W.J., Gooren L.J., Kaufman J.M., Legros J.J., Lunenfeld B., Morales A., Morley J.E., Schulman C., Thompson I.M., Weidner W., Wu F.C., International Society of Andrology (ISA); International Society for the Study of Aging Male (ISSAM); European Association of Urology (EAU); European Academy of Andrology (EAA); American Society of Andrology (ASA) Investigation, treatment, and monitoring of late-onset hypogonadism in males: ISA, ISSAM, EAU, EAA, and ASA recommendations. J Androl. 2009;30:1–9. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.108.006486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.White K.P., Speechley M., Harth M., Ostbye T. Fibromyalgia in rheumatology practice: a survey of Canadian rheumatologists. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:722–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolfe F., Smythe H.A., Yunus M.B., Bennett R.M., Bombardier C., Goldenberg D.L., Tugwell P., Campbell S.M., Abeles M., Clark P., Fam A.G., Farber S.J., Fiechtner J.J., Franklin C.M., Gatter R.A., Hamaty D., Lessard J., Lichtbroun A.S., Masi A.T., McCain G.A., Reynolds W.J., Romano T.J., Russell I.J., Sheon R.P. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:160–172. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu F.C., Tajar A., Beynon J.M., Pye S.R., Silman A.J., Finn J.D., O’Neill T.W., Bartfai G., Casanueva F.F., Forti G., Giwercman A., Han T.S., Kula K., Lean M.E., Pendleton N., Punab M., Boonen S., Vanderschueren D., Labrie F., Huhtaniemi I.T. Identification of late-onset hypogonadism in middle-aged and elderly men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:123–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0911101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu F.C., Tajar A., Pye S.R., Silman A.J., Finn J.D., O’Neill T.W., Bartfai G., Casanueva F., Forti G., Giwercman A., Huhtaniemi I.T., Kula K., Punab M., Boonen S., Vanderschueren D. Hypothalamic–pituitary–testicular axis disruptions in older men are differentially linked to age and modifiable risk factors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2737–2745. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]