Abstract

Rationale

Methamphetamine abuse and dependence are significant public-health concerns. Behavioral therapies are effective for reducing methamphetamine use. However, many patients enrolled in behavioral therapies are unable to achieve significant periods of abstinence suggesting other strategies like pharmacotherapy are needed.

Objectives

This experiment determined the physiological and subjective effects of acutely administered intranasal methamphetamine during atomoxetine maintenance in seven non-treatment seeking stimulant-dependent participants. Atomoxetine was chosen for study because it blocks reuptake at the norepinephrine transporter and increases extracellular dopamine levels in the prefrontal cortex. In this way, atomoxetine might function as an agonist replacement therapy for stimulant-dependent patients

Methods

After at least 7 days of maintenance on atomoxetine (0 and 80 mg/day), participants were administered ascending doses of intranasal methamphetamine (0, 5, 10, 20 and 30 mg) across two experimental sessions. Intranasal methamphetamine doses were separated by 90 minutes.

Results

Intranasal methamphetamine produced prototypical physiological and subjective effects (e.g., increased heart rate, blood pressure, temperature and subjective ratings of Good Effects). Atomoxetine maintenance augmented the heart rate-increasing effects of methamphetamine, but attenuated the pressor effects. The subjective effects of intranasal methamphetamine were similar during atomoxetine and placebo maintenance.

Conclusions

These results suggest that methamphetamine can be safely administered to participants maintained on atomoxetine, but whether it might be an effective pharmacotherapy for methamphetamine dependence remains to be determined.

Keywords: Methamphetamine, Atomoxetine, Humans, Pharmacotherapy, Subjective Effects, Physiological Effects

1. Introduction

Methamphetamine abuse and dependence are significant public-health concerns. Treatment admissions for methamphetamine use more than doubled from 1998 to 2007 in the United States (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2009). Estimates from the most recent available data indicate that the total cost for methamphetamine abuse in the United States was over $23 billion in 2005 (Nicosia, Reardon, Lorenz et al., 2009). These costs include premature mortality, crime, lost productivity, environmental damage, and medical conditions such as cardiovascular insults, cognitive dysfunction and infectious disease (Pasic, Russo, Rieset al., 2007; Shoptaw, King, Landstrom et al., 2009).

Behavioral treatments like contingency management and cognitive-behavioral therapy effectively reduce methamphetamine use (Lee and Rawson, 2008; Roll, Petry, Stitzer et al., 2006; Shoptaw, Klausner, Reback et al., 2006; Smout, Longo, Harrison et al., 2010). However, many patients enrolled in behavioral treatment programs are unable to achieve significant periods of abstinence suggesting other strategies like pharmacotherapy are needed. Despite intense research efforts, a widely effective pharmacotherapy has not yet been identified for methamphetamine dependence (for reviews, see Elkashef, Vocci, Hanson et al., 2008; Karila, Weinstein, Aubin et al. 2010; Rush, Vansickel, Lile et al., 2009; Vocci and Appel, 2007).

Atomoxetine (Strattera®) is effective for the treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in children, adolescents and adults (e.g., Michelson, Faries, Wernicke et al., 2001; Michelson, Allen, Busner et al., 2002; Michelson, Adler, Spencer et al., 2003; Simpson and Plosker, 2004a, 2004b). While effective ADHD pharmacotherapies like methylphenidate and d-amphetamine are traditionally defined as psychomotor stimulants, atomoxetine is marketed as a non-stimulant. Atomoxetine produces pharmacological effects that are similar to those observed with prototypical stimulants (Bymaster, Katner, Nelson et al., 2002; Fleckenstein, Gibb and Hanson, 2000; Johanson and Fischman, 1989; Kuczenski and Segal, 1997). Atomoxetine blocks reuptake at the norepinephrine transporter and increases extracellular dopamine levels in the prefrontal cortex (Bymaster, Katner, Nelson et al., 2002). The behavioral effects of atomoxetine overlap to some extent with those of prototypical stimulants (e.g., Johanson and Barrett, 1993; Kleven, Anthony and Woolverton 1990; Lile, Stoops, Durell et al., 2006; Spealman, 1995). These findings suggest that atomoxetine might potentially function as an agonist replacement therapy for stimulant-dependent patients. Importantly, however, atomoxetine has less abuse potential than prototypical stimulants like methylphenidate and d-amphetamine (Heil, Holmes, Bickel et al., 2002; Lile, Stoops, Durell et al., 2006; Wee and Woolverton, 2004). Atomoxetine is not classified as a scheduled drug by the Drug Enforcement Agency, whereas both methylphenidate and d-amphetamine have received Schedule II classification.

We know of only two published reports that determined the combined effects of a stimulant and atomoxetine (Sofuoglu, Poling, Hill et al. 2009; Stoops, Blackburn, Hudson et al., 2008). In the more recent study, participants (N=10) were maintained on a single daily dose of atomoxetine (40 mg/day) or placebo for four days in random order (Sofuoglu, Poling, Hill et al. 2009). On the fourth day of maintenance, participants received a single oral administration of d-amphetamine (20 mg/kg). Outcome measures included subjective, cardiovascular and endocrine responses to d-amphetamine. Ratings of Stimulated, Good Effects and High were significantly lower during atomoxetine maintenance relative to placebo maintenance, and similar effects were observed on cortisol and systolic and diastolic blood pressure. In a previous study conducted in our laboratory, the physiological and subjective effects of acute intranasal doses of cocaine were assessed during atomoxetine maintenance (Stoops, Blackburn, Hudson et al., 2008). Seven cocaine-dependent participants were maintained on doses of atomoxetine (0 [lead in], 5, 10, 20 and 0 [washout] mg, four times daily) for 3–5 days prior to completing experimental sessions in which ascending doses of intranasal cocaine (4, 20, 40 and 60 mg) were administered. Cocaine produced prototypical cardiovascular and subjective effects. Atomoxetine attenuated the systolic pressure-increasing effects and enhanced the heart rate-increasing effects of cocaine, but did not alter the abuse-related subjective effects of cocaine to a statistically significant degree.

The purpose of the present experiment, then, was to further determine the safety and potential efficacy of atomoxetine as a putative pharmacotherapy of amphetamine dependence. To accomplish this aim, the acute physiological, subjective and performance effects of intranasal methamphetamine (0 [placebo], 5, 10, 20 and 30 mg) were assessed in stimulant-dependent participants maintained on atomoxetine (0 and 80 mg/day for at least 7 days). We hypothesized that these intranasal methamphetamine doses would be well tolerated during atomoxetine maintenance and atomoxetine maintenance would attenuate some of the abuse-related subjective effects of intranasal methamphetamine.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Seven non-treatment-seeking adult participants with recent histories of illicit stimulant use completed this within-subject, placebo-controlled study. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Kentucky Medical Center approved this study and participants gave their written informed consent prior to participating. Participants were paid for their participation.

Prior to enrollment, all potential participants underwent a comprehensive physical- and mental-health screening. The screening measures included a computerized version of the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV, medical-history questionnaire, general-health questionnaire, mini-mental status examination, drug-use questionnaire, over-the-counter drug-use questionnaire, Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST) (Skinner, 1982) and Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (MAST) (Selzer, 1971). Scores of at least five on the DAST and MAST indicate possible drug or alcohol abuse.

A psychiatrist (L.R.H., P.E.A.G. or his designee) interviewed and examined each potential participant, confirmed the diagnosis of stimulant dependence from the computerized SCID and deemed him or her to be appropriate for the study. Routine clinical laboratory blood chemistry tests, vital signs assessment and an electrocardiogram were also conducted. Potential participants with histories of serious physical disease or current physical disease, impaired cardiovascular functioning, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, seizure, head trauma or CNS tumors or current or past histories of serious psychiatric disorder (i.e., Axis I, DSM IV), other than substance abuse or dependence, were excluded from participation. Participants had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) self-reported recent stimulant use, (2) confirmation of recent stimulant use by a positive urine screen during the initial screening process and (3) fulfill diagnostic criteria for stimulant dependence. All participants were in good health with no contraindications to stimulants.

All subjects reported current illicit stimulant use in the month prior to screening (8–30 days; mean = 20 days), which was verified by drug urinalysis testing during screening. These subjects all reported the use of cocaine and met diagnostic criteria for cocaine dependence. Three of the 7 subjects had experience with amphetamine. After study completion, subjects attended follow-up visits to complete self-reported drug use questionnaires and provide urine samples for illicit drug screening to monitor possible changes in patterns and types of drugs used. No changes were noted.

Participants ranged in age from 31 to 50 years (mean: 39 years) and in weight from 61 to 99 kg (mean: 87 kg). Six of these participants were male and one was female. Six participants were Black and one was Hispanic. Participants scored between 3 and 18 (mean: 10) on the DAST. All of the participants reported smoking tobacco cigarettes daily (range: 3–20 cigarettes per day; mean: 10 cigarettes). Participants also reported use of a wide range of substances including alcohol, caffeine, marijuana, opiates, nicotine and sedatives, but did not meet dependence criteria for any drugs other than cocaine.

2.2. General Procedures

Participants were enrolled as inpatients at the University of Kentucky Chandler Medical Center Clinical Research Development and Operations Center (CR-DOC) for up to 23 days and participated in one practice and four experimental sessions. Participants were informed that during their participation they would receive various drugs, administered orally or intranasally, that could include placebo, atomoxetine or methamphetamine. Participants were instructed that these medications could be administered in combination. Other than receiving this general information, participants were blind to the type and dose of drug administered. Participants were told that the purpose of the study was to determine how different drugs affect physiology, mood and behavior. Other than this general explanation of purpose, participants were given no instruction of what they were “supposed” to do or of what outcomes might be expected.

Following admission, participants were then allowed to acclimate to the CR-DOC for one day, during which they were observed for signs of drug or alcohol withdrawal. No participant showed signs of withdrawal. After study completion, subjects attended follow-up visits to complete self-reported drug use questionnaires and provide urine samples for illicit drug screening to ensure that their patterns and types of drug use had not changed.

2.2.1. Practice Session

Following the acclimation period, participants completed one practice session to familiarize them with experimental measures. Experimental medications were not administered during this session.

2.2.2. Drug Maintenance Days

Drug maintenance began on the day immediately following the practice session and continued throughout the protocol. Placebo or atomoxetine was administered orally at 0700 and 1900 h. Order of drug maintenance was counterbalanced across participants. On the first day of the active atomoxetine maintenance phase, the dose per day was 20 mg atomoxetine (i.e., 10 mg b.i.d.). For the next two days, the dose per day was 40 mg atomoxetine (i.e., 20 mg b.i.d.). For the remaining days of atomoxetine maintenance (i.e., at least 4 days), the dose per day was 80 mg atomoxetine (i.e., 40 mg b.i.d.).

After at least seven days of maintenance on placebo or atomoxetine, participants completed two experimental sessions. After completing these sessions, participants moved to the other maintenance condition and then completed two more experimental sessions after at least seven days of maintenance on that condition. Occasionally, participants had to be maintained for more than seven days to avoid conducting experimental sessions on weekends, when medical coverage at the CR-DOC was limited. Therefore, participants were maintained on placebo or atomoxetine for a minimum of seven days and a maximum of nine days in addition to the two experimental session days for each condition.

2.2.3. Experimental Sessions

Experimental sessions were conducted in two blocks of two sessions each. Participants received the appropriate maintenance dose at 0700 h on the morning of all experimental sessions. Experimental sessions started at 0800 h and lasted 5.5 h. Three intranasal methamphetamine doses were given in each session in ascending order 1.5 h apart (0 [placebo] 5 and 10 mg for Sessions 1 and 3 [i.e., the first session under a maintenance condition] and 0, 20 and 30 mg for Sessions 2 and 4 [i.e., the second session under a maintenance condition]). Physiological measures were recorded immediately prior to each drug administration and every 15 min for 75 min after each dose. Subjective and performance measures were completed prior to initial drug administration, immediately after each drug administration and every 15 min for 75 min after each dose. Urine and expired breath samples were collected prior to each session to confirm drug and alcohol abstinence, respectively. Participants occasionally tested positive for amphetamine, which coincided with the administration of the experimental medications. Participants tested negative for all other drug and alcohol use. Daily pregnancy tests for the female participant were negative throughout enrollment.

2.2.4. Testing Room

The testing room for all sessions consisted of a table and chair for the research assistant and nurse, a hospital bed for the participant, an Apple iBook laptop computer (Apple Computer Inc., Cupertino, CA) and an automated ECG and blood pressure monitor (Dinamap Pro 1000 Vital Signs monitor, Critikon Company L.L.C., Tampa, FL). A crash cart was available in case of a medical emergency.

2.3. Physiological Measures

Heart rate, blood pressure and oral temperature were recorded immediately prior to each methamphetamine dose administration and at 15 min intervals thereafter for 75 min. Cardiac rhythmicity was recorded throughout experimental sessions. If heart rate exceeded 130 beats per minute, systolic blood pressure exceeded 180 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure exceeded 120 mmHg or clinically significant ECG changes occurred following administration of methamphetamine at any point during the experiment, participation was terminated. No participant was excluded from the study for exceeding these parameters.

2.4. Subject Drug-Effect Questionnaires and Performance Task

The subjective drug-effect questionnaires and the performance task were administered on the laptop computer in a fixed order. Participants completed all experimental measures prior to the initial dose administration, immediately after dose administration and every 15 min for 75 min after each methamphetamine dose.

2.4.1. Drug-Effect Questionnaire

The Drug-Effect Questionnaire consisted of 20 items, which are sensitive to the acute effects of stimulants, as well as the effects of stimulant maintenance (Rush, Stoops and Hays, 2009; Rush, Stoops, Lile et al., 2011). The 20 items were presented on the computer screen, one at a time. Participants rated each item by placing a mark along a 100-unit line anchored with “False” on the left side and “True” on the right side.

2.4.2. Adjective-Rating Scale

This scale consisted of 32 items that load into two subscales: sedative and stimulant (Oliveto, Bickel, Hughes et al., 1992). Participants rated each item using a computer mouse to point to and select among one of five response options: Not At All, A Little Bit, Moderately, Quite A Bit, and Extremely (scored numerically from 0 to 4, respectively). Responses to individual items were summed to produce a composite score for each subscale. The maximum total for each subscale was 64.

2.4.3. UKU Side Effects Scale

CR-DOC nursing staff also completed the Udvalg for Kliniske UndersØgelser (UKU) Side Effects Rating Scale daily (Lingjaerde, Ahlfors, Bech et al., 1987). Although not analyzed statistically, side effects reported on these scales were monitored regularly by unit physicians. No participants were discontinued from participation due to side effects.

2.4.4. Digit-Symbol-Substitution Test

The Digit-Symbol-Substitution Test (DSST) is widely used in human behavioral pharmacology research to assess changes in psychomotor performance following drug administration. Briefly, participants matched geometric patterns displayed on the computer screen with corresponding numbers on a numeric keypad. Volunteers had 90 seconds to enter as many geometric patterns as possible. The dependent measures were the number of geometric patterns the participant attempted to enter (i.e., trials completed) and the number of patterns the participant entered correctly (i.e., trials correct).

2.5. Drug Administration

All drugs were administered in a double-blind fashion. Atomoxetine (10, 20 and 40 mg, Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN) doses were prepared by over-encapsulating commercially available drug in a size-0 capsule. Cornstarch was then used to fill the remainder of the capsule. Placebo capsules contained only cornstarch.

Methamphetamine doses (0 mg [placebo], 5, 10, 20 and 30 mg) were prepared by combining the appropriate amount of methamphetamine HCl (National Institute on Drug Abuse, Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) with lactose to equal a total of 100 mg powder.

During each methamphetamine administration, a nurse presented the participant with the powder, a mirror and a standard razor blade. The participant was instructed to divide the powder into two even "lines" and insufflate one line of powder through each nostril using a 65-mm plastic straw within 2 minutes.

References below to methamphetamine alone pertain to those instances in which an active dose, 5, 10, 20 or 30 mg, was administered during maintenance on 0 mg atomoxetine. References to placebo pertain to sessions in which 0 mg methamphetamine was administered during maintenance on 0 mg atomoxetine.

2.6. Data Analysis

Data from the experimental sessions were analyzed as peak effect (i.e., the maximum score observed following each methamphetamine administration). Peak-effect data were analyzed using a two factor repeated-measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with Atomoxetine maintenance condition (0 and 80 mg/day) and Methamphetamine dose (0 [placebo, averaged across the two administrations within a maintenance condition], 5 10, 20 and 30 mg) as the factors (StatView, Cary, NC). If a significant effect of methamphetamine was detected, post-hoc tests were conducted to compare each of the active drug conditions with placebo. If a dose of methamphetamine alone differed significantly from placebo, additional post-hoc tests were conducted to compare the effects of these doses of methamphetamine alone and during maintenance on atomoxetine. Effects were considered significant for p≤0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Physiological Measures

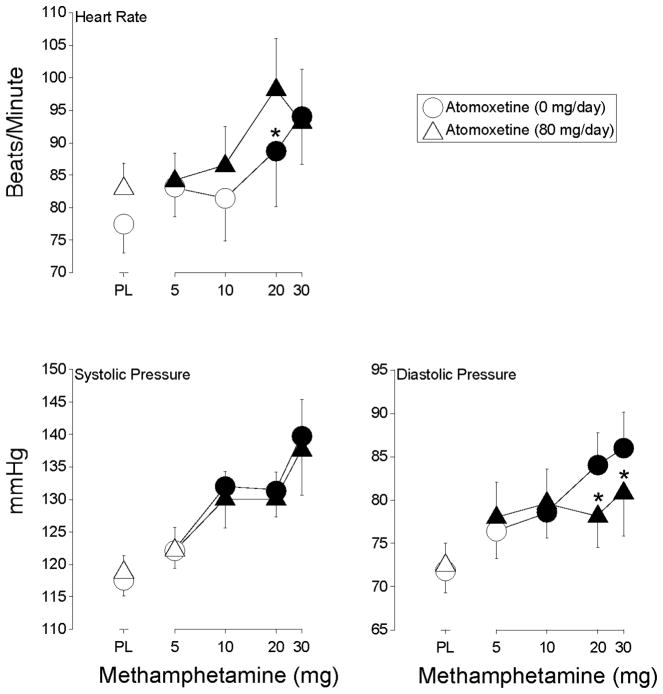

3.1.1. Heart Rate

Methamphetamine increased heart rate (F4,24 = 6.1, p < 0.002). The two higher doses of methamphetamine, 20 and 30 mg, increased heart rate significantly above placebo level during placebo maintenance, while all doses of methamphetamine did so during atomoxetine maintenance (Figure 1). Heart rate was significantly higher after administration of 20 mg intranasal methamphetamine during atomoxetine maintenance relative to when this dose of intranasal methamphetamine was administered alone.

Figure 1.

Shown are dose-response functions for methamphetamine during maintenance on placebo (circles) and 80-mg/day atomoxetine (triangles) for heart rate, systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure. Data are expressed as peak effect (i.e., the maximum score observed following each methamphetamine administration). Data points represent means for seven volunteers. X-axis: Intranasal methamphetamine dose. Filled symbols indicate the data point differs significantly from the placebo condition (i.e., 0 mg methamphetamine during maintenance on 0 mg atomoxetine). An asterisk indicates that the data point is significantly different from the corresponding dose of methamphetamine during maintenance on 0 mg d-amphetamine. Error bars are one S.E.M.

3.1.2. Blood Pressure

Methamphetamine increased systolic and diastolic blood pressure (F4,24 = 14.3 and 11.8, respectively, p < 0.0001). The three higher doses of methamphetamine (i.e., 10, 20 and 30 mg) increased systolic pressure significantly above placebo levels regardless of the maintenance condition (Figure 1). The three higher doses of methamphetamine increased diastolic pressure significantly above placebo levels during placebo maintenance, while each of the methamphetamine doses did so during atomoxetine maintenance (Figure 1). However, diastolic blood pressure was significantly lower following the administration of the two higher doses of methamphetamine during atomoxetine maintenance relative to when these doses were administered alone.

3.1.3. Temperature

Each dose of methamphetamine increased temperature significantly above placebo level regardless of the maintenance condition (i.e., main effect of methamphetamine [F4,24 = 3.2, p < 0.03]) (data not shown).

3.2. Subjective Drug Effect Questionnaires and Performance Task

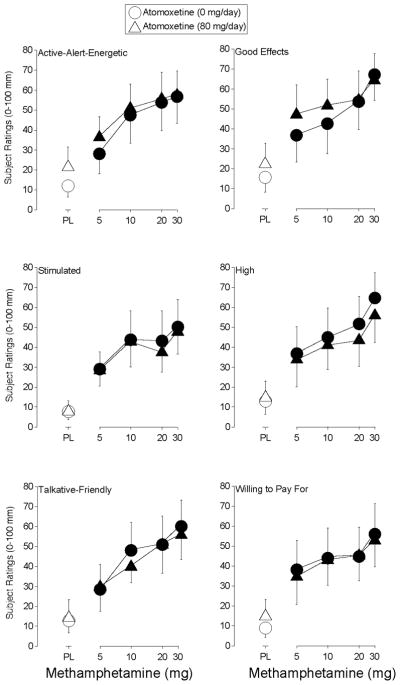

3.2.1. Drug-Effect Questionnaire

Methamphetamine produced a significant effect on 11 items on the Drug-Effect Questionnaire: Any Effect, Active-Alert-Energetic, Good Effects, High, Like Drug, Willing to Pay For, Performance Impaired, Rush, Stimulated, Willing to Take Again and Talkative-Friendly (F4,24 values > 3.1, p < 0.04). Figure 2 shows the effects methamphetamine during placebo and atomoxetine maintenance for ratings of Active-Alert-Energetic, Good Effects, Stimulated, High, Talkative-Friendly, and Willing to Pay For. This figure shows that each dose of methamphetamine increased ratings on each of these items, regardless of the maintenance condition. Similar effects were observed on ratings of Rush (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Shown are dose-response functions for methamphetamine during maintenance on placebo (circles) and 80-mg/day atomoxetine (triangles) for ratings of Active-Alert-Energetic, Stimulated, Talkative-Friendly, Good Effects, High and Willing to Pay For on the Drug-Effect Questionnaire. Data are expressed as peak effect (i.e., the maximum score observed following each methamphetamine administration). Other details are the same as in Figure 1.

Ratings of Any Effect, Like Drug and Willing to Take Again were similarly affected except that significant increases were observed following administration of placebo during atomoxetine maintenance (data not shown). Methamphetamine (10 mg) increased ratings of Performance Impaired during placebo maintenance, while the two higher doses of methamphetamine did so during atomoxetine maintenance (data not shown).

3.2.2. Adjective-Rating Scale

Methamphetamine increased ratings on the Stimulant Scale of the Adjective-Rating Scale (F4,28 = 9.1, p < 0.0002). Each of the doses of methamphetamine increased ratings on this scale significantly above placebo levels during placebo maintenance, while only the three higher methamphetamine doses did so during atomoxetine maintenance. Atomoxetine maintenance did not significantly alter the effects of methamphetamine.

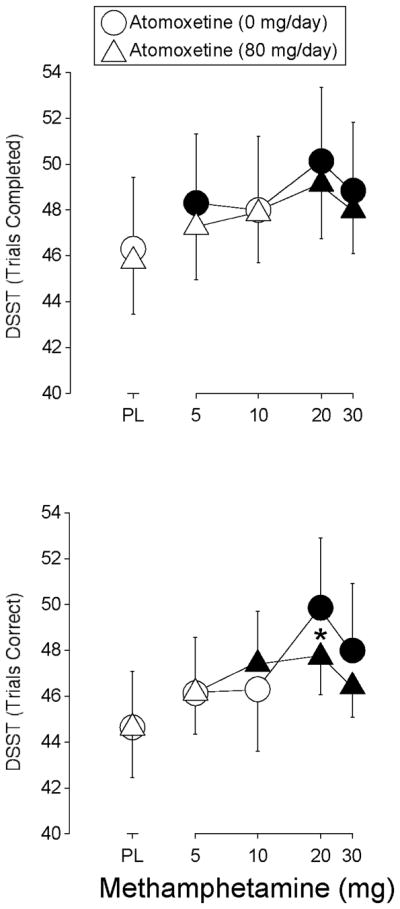

3.2.3. Digit-Symbol-Substitution Test (DSST)

Methamphetamine increased the number of trials attempted (F4,28 = 8.9, p < 0.0002) and number of trials correct (F4,28 = 13.9, p = 0.0001) on the DSST. Intranasal methamphetamine (5, 20 and 30 mg) alone increased the number of trials attempted significantly above placebo levels during placebo maintenance, while 20 and 30 mg intranasal methamphetamine did so during atomoxetine maintenance (Figure 3). Atomoxetine maintenance did not significantly alter the effects of methamphetamine on the number of trials attempted. The two highest doses of intranasal methamphetamine alone increased the number of trials correct significantly above placebo levels during placebo maintenance, while the three highest intranasal methamphetamine doses did so during atomoxetine maintenance (Figure 3). The number of trials completed correctly was significantly lower following the administration of 20 mg methamphetamine during atomoxetine maintenance relative to when this methamphetamine dose was administered alone.

Figure 3.

Shown are dose-response functions for methamphetamine during maintenance on placebo (circles) and 80-mg/day atomoxetine (triangles) for trials completed and trials correct on the DSST. Data are expressed as peak effect (i.e., the maximum score observed following each methamphetamine administration). Other details are the same as in Figure 1.

4. Discussion

The present study examined the acute physiological and subjective effects of a range of doses of intranasal methamphetamine (0, 5, 10, 20 and 30 mg) in participants maintained on oral atomoxetine (0 or 80 mg/day for at least 7 days). Intranasal methamphetamine increased heart rate, blood pressure and temperature as a function of dose, and produced a constellation of positive subjective drug effects (e.g., Like Drug, Good Effects, Willing to Take Again). Atomoxetine maintenance alone was generally devoid of physiological and subjective effects. Atomoxetine maintenance augmented the heart rate-increasing effects of an intermediate dose of methamphetamine (20 mg). By contrast, atomoxetine maintenance attenuated methamphetamine-induced increases in diastolic pressure. Atomoxetine maintenance did not alter the subjective effects of intranasal methamphetamine.

Intranasal methamphetamine increased heart rate, blood pressure and temperature during placebo maintenance. While the effects of intranasal methamphetamine were generally an orderly function of dose, they were not clinically significant and no unexpected or serious adverse events occurred. Atomoxetine maintenance augmented the heart rate-increasing effects of an intermediate dose of methamphetamine (20 mg). While statistically significant, the magnitude of the augmentation of the heart rate-increasing effects of 20 mg methamphetamine was modest (i.e., approximately 10 bpm). Atomoxetine augmented the heart rate-increasing effects of d-amphetamine in a previous study, although this effect did not attain statistical significance (Sofuoglu, Poling, Hill et al. 2009). The more robust effects of atomoxetine on amphetamine-induced increases in heart rate observed in the present study may be due to the use of a higher maintenance dose than was tested in the previous study (i.e., 80 versus 40 mg/day). Atomoxetine maintenance attenuated methamphetamine-induced increases in diastolic pressure. The cardiovascular effects observed with the methamphetamine-atomoxetine combinations are qualitatively similar to those observed following d-amphetamine administration to participants maintained on atomoxetine (Sofuoglu, Poling, Hill et al. 2009). The relative safety of acute administrations of methamphetamine during atomoxetine maintenance suggests that higher doses of the constituent compounds could be tested in future studies.

Intranasal methamphetamine produced prototypical subjective drug effects (e.g., increased ratings of Good Effects, Like Drug, Wiling to Take Again). The magnitude of the effects of intranasal methamphetamine observed in the present experiment was similar in magnitude to those reported previously in studies that used comparable doses and subjective-effects instruments (Hart, Gunderson, Perez et al., 2008). In the present experiment, 20 and 30 mg intranasal methamphetamine increased subject ratings to approximately 50–65 mm on a 100-mm visual analog scale). As noted above, these two doses of methamphetamine were administered during the same experimental session but separated by 90 minutes. In the previous study, a bolus dose of 50 mg intranasal methamphetamine increased subjective ratings to approximately 75 mm on a 100-mm visual-analog scale (Hart, Gunderson, Perez et al., 2008).

The subjective effects of intranasal methamphetamine were not affected by atomoxetine maintenance relative to placebo. The results of the present experiment are concordant with those from a previous human laboratory experiment that assessed the subjective effects of intranasal cocaine in participants maintained on atomoxetine (Stoops, Blackburn, Hudson et al., 2008). By contrast, the failure of atomoxetine to attenuate the subjective effects of methamphetamine in the present experiment is discordant with the results of a previous study that reported that atomoxetine (40 mg/day for 4 days) attenuated some of the positive subjective effects of 20 mg d-amphetamine (Sofuoglu, Poling, Hill et al. 2009). The reason for the discrepancy between the present experiment and the previous study is unknown, but three explanations seem plausible. First, the present experiment tested methamphetamine while the previous study used d-amphetamine. While d-amphetamine and methamphetamine produce a similar constellation of effects (Sevak, Stoops, Hays et al., 2009), there are some neuropharmacological differences between these congeners. d-Amphetamine and methamphetamine are equally potent in terms of promoting dopamine release, but there are potency differences between them in terms of norepinephrine release (Rothman, Baumann, Dersch et al., 2001). These differences may make it more difficult to attenuate the subjective effects of methamphetamine with atomoxetine. Second, d-amphetamine was administered orally in the previous study (Sofuoglu, Poling, Hill et al. 2009) whereas methamphetamine was administered intranasally in the present study. Intranasal drug administration is associated with more rapid penetration of the central nervous system. Drug effects that onset rapidly may be more difficult to attenuate pharmacologically than those that occur slowly. Third, the participants tested in the previous study were quite different from those enrolled in the present experiment. Participants in the previous study were without histories of drug abuse or dependence. Participants in the present experiment, by contrast, had to meet diagnostic criteria for a stimulant use disorder. Perhaps the subjective effects of amphetamines are more amenable to pharmacological manipulation in individuals with less extensive histories of stimulant use. Consistent with this notion, the results of some clinical trials suggest that patients with lower baseline methamphetamine use respond better to pharmacotherapy (Elkashef, Rawson, Anderson et al., 2008; Shoptaw, Heinzerling, Rotheram-Fuller et al., 2008).

At least three caveats of the present experiment warrant discussion. First, the doses of methamphetamine were tested in ascending order for safety purposes. Future studies should administer the methamphetamine doses in a randomized fashion. Second, two active methamphetamine doses were administered in each experimental session (i.e., 5 and 10 mg; 20 and 30 mg). Given the relatively long half-life of methamphetamine, it is likely that the initial doses influenced the effects of the subsequent doses. Future research should test each of the methamphetamines doses on separate days. A third caveat is that this study used subjective-effects questionnaires. These instruments were selected because they could easily be incorporated into a safety and tolerability study design as a secondary outcome measure. While many human laboratory studies have used subjective-effects questionnaires to determine the initial efficacy of pharmacotherapies for stimulant dependence, these instruments are prone to both false-positive and false-negative results. Future research should use more sophisticated behavioral arrangements that are predictive of pharmacotherapy effectiveness such as drug self-administration (Comer, Ashworth, Foltin et al., 2008; Haney and Spealman, 2008).

Subsequent studies should also consider other aspects of stimulant dependence that are unrelated to the acute effects of methamphetamine but could be a barrier to recovery. For example, stimulant abusers often perform more poorly than matched controls on some neurocognitive tasks (e.g., Jovanovski, Erb and Zakzanis, 2005; Rendell, Mazur and Henry, 2009; Salo, Nordahl, Natsuaki et al., 2007; van der Plas, Crone, van den Wildenberg et al., 2009). Perhaps, pharmacologically improving neurocognitive functioning would allow stimulant dependent patients to benefit more fully from cognitive-behavioral therapies thereby effecting reductions in drug use. In this respect, atomoxetine might be a viable pharmacotherapy for stimulant dependence because it has been shown to improve some cognitive deficits in patients with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (e.g., Chamberlain, Del Campo, Dowson et al., 2007; Faraone, Biederman, Spencer et al., 2005).

In summary, the present study demonstrated that acute intranasal methamphetamine doses were well tolerated during atomoxetine maintenance. These results support further testing with methamphetamine during atomoxetine maintenance, but using a more rigorous randomized dosing design. Subsequent studies should include measures that model drug use in the natural environment, and consider outcomes associated with stimulant dependence beyond acute drug effects. For example, future research could evaluate the impact of medication maintenance on measures of cognitive function and model effective behavioral therapies to assess potential interactions between pharmacological and behavioral treatments.

Highlights.

Methamphetamine abuse and dependence are significant public-health concerns.

This experiment determined the physiological and subjective effects of methamphetamine during atomoxetine maintenance.

Atomoxetine maintenance augmented the heart rate-increasing effects of methamphetamine and attenuated the pressor effects, but did not alter the subjective effects.

Methamphetamine can be safely administered to participants maintained on atomoxetine.

Additional research in humans is needed to determine whether atomoxetine might attenuate the behavioral effects of methamphetamine under different behavioral arrangements (e.g., drug self-administration).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA025032 to Craig R. Rush and K01 DA018772 to Joshua A. Lile) and by the University of Kentucky CR-DOC. The authors have no financial relationships with these funding sources and declare no conflicts of interest relevant to this project. The authors wish to thank Bryan Hall, Michelle Gray, Erika Pike and Sarah Veenema for technical assistance and Frances Wagner for medical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bymaster FP, Katner JS, Nelson DL, Hemrick-Luecke SK, Threlkeld PG, Heiligenstein JH, Morin SM, Gehlert DR, Perry KW. Atomoxetine increases extracellular levels of norepinephrine and dopamine in prefrontal cortex of rat: a potential mechanism for efficacy in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:699–711. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, Del Campo N, Dowson J, Muller U, Clark L, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ. Atomoxetine improved response inhibition in adults with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:977–984. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer SD, Ashworth JB, Foltin RW, Johanson CE, Zacny JP, Walsh SL. The role of human drug self-administration procedures in the development of medications. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkashef A, Vocci F, Hanson G, White J, Wickes W, Tiihonen J. Pharmacotherapy of methamphetamine addiction: an update. Subst Abus. 2008;29:31–49. doi: 10.1080/08897070802218554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkashef AM, Rawson RA, Anderson AL, Li SH, Holmes T, Smith EV, Chiang N, Kahn R, Vocci F, Ling W, Pearce VJ, McCann M, Campbell J, Gorodetzky C, Haning W, Carlton B, Mawhinney J, Weis D. Bupropion for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1162–1170. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Biederman J, Spencer T, Michelson D, Adler L, Reimherr F, Seidman L. Atomoxetine and stroop task performance in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15:664–670. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleckenstein AE, Gibb JW, Hanson GR. Differential effects of stimulants on monoaminergic transporters: Pharmacological consequences and implications for neurotoxicity. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;406:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00639-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Spealman R. Controversies in translational research: drug self-administration. Psychopharmacology. 2008;199:403–419. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1079-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CL, Gunderson EW, Perez A, Kirkpatrick MG, Thurmond A, Comer SD, Foltin RW. Acute physiological and behavioral effects of intranasal methamphetamine in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1847–1855. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil SH, Holmes HW, Bickel WK, Higgins ST, Badger GJ, Laws HF, Faries DE. Comparison of the subjective, physiological, and psychomotor effects of atomoxetine and methylphenidate in light drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;67:149–156. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanson CE, Barrett JE. The discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine in pigeons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;267:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanson CE, Fischman MW. The pharmacology of cocaine related to its abuse. Pharmacol Rev. 1989;41:3–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovski D, Erb S, Zakzanis KK. Neurocognitive deficits in cocaine users: a quantitative review of the evidence. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2005;27:189–204. doi: 10.1080/13803390490515694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karila L, Weinstein A, Aubin HJ, Benyamina A, Reynaud M, Batki SL. Pharmacological approaches to methamphetamine dependence: a focused review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69:578–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03639.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleven MS, Anthony EW, Woolverton WL. Pharmacological characterization of the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;254:312–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczenski R, Segal DS. Effects of methylphenidate on extracellular dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine: comparison with amphetamine. J Neurochem. 1997;68:2032–2037. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68052032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee NK, Rawson RA. A systematic review of cognitive and behavioural therapies for methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008;27:309–317. doi: 10.1080/09595230801919494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lile JA, Stoops WW, Durell TM, Glaser PE, Rush CR. Discriminative-stimulus, self-reported, performance, and cardiovascular effects of atomoxetine in methylphenidate-trained humans. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;14:136–147. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingjaerde O, Ahlfors UG, Bech P, Dencker SJ, Elgen K. The UKU side effect rating scale. A new comprehensive rating scale for psychotropic drugs and a cross-sectional study of side effects in neuroleptic-treated patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1987;334:1–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1987.tb10566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelson D, Allen AJ, Busner J, Casat C, Dunn D, Kratochvil C, Newcorn J, Sallee FR, Sangal RB, Saylor K, West S, Kelsey D, Wernicke J, Trapp NJ, Harder D. Once-daily atomoxetine treatment for children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1896–1901. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelson D, Faries D, Wernicke J, Kelsey D, Kendrick K, Sallee FR, Spencer T. Atomoxetine in the treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-response study. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E83. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.5.e83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelson D, Adler L, Spencer T, Reimherr FW, West SA, Allen AJ, Kelsey D, Wernicke J, Dietrich A, Milton D. Atomoxetine in adults with ADHD: Two randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:112–120. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicosia N, Reardon E, Lorenz K, Lynn J, Buntin MB. The Medicare hospice payment system: a consideration of potential refinements. Health Care Financ Rev. 2009;30:47–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveto AH, Bickel WK, Hughes JR, Shea PJ, Higgins ST, Fenwick JW. Caffeine drug discrimination in humans: Acquisition, specificity and correlation with self-reports. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;261:885–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasic J, Russo JE, Ries RK, Roy-Byrne PP. Methamphetamine users in the psychiatric emergency services: a case-control study. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2007;33:675–86. doi: 10.1080/00952990701522732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendell PG, Mazur M, Henry JD. Prospective memory impairment in former users of methamphetamine. Psychopharmacology. 2009;203:609–616. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1408-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM, Petry NM, Stitzer ML, Brecht ML, Peirce JM, McCann MJ, Blaine J, MacDonald M, DiMaria J, Lucero L, Kellogg S. Contingency management for the treatment of methamphetamine use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1993–1999. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman RB, Baumann MH, Dersch CM, Romero DV, Rice KC, Carroll FI, Partilla JS. Amphetamine-type central nervous system stimulants release norepinephrine more potently than they release dopamine and serotonin. Synapse. 2001;39:32–41. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(20010101)39:1<32::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush CR, Stoops WW, Hays LR. Cocaine effects during d-amphetamine maintenance: A human laboratory analysis of safety, tolerability and efficacy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:261–271. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush CR, Stoops WW, Lile JA, Glaser PEA, Hays LR. Subjective and physiological effects of acute intranasal methamphetamine during d-amphetamine maintenance. Psychopharmacology. 2011;214:665–674. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush CR, Vansickel AR, Lile JA, Stoops WW. Evidence-based treatment of amphetamine dependence: Behavioral and pharmacological approaches. In: Cohen L, Collins FL, Young AM, McChargue DE, Leffingwell TR, Cook KL, editors. Pharmacology and Treatmment of Substance Abuse: Evidence- and Outcome-Based Perspectives. New York: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group; 2009. pp. 335–358. [Google Scholar]

- Salo R, Nordahl TE, Natsuaki Y, Leamon MH, Galloway GP, Waters C, Moore CD, Buonocore MH. Attentional control and brain metabolite levels in methamphetamine abusers. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:1272–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzer ML. The Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test: the quest for a new diagnostic instrument. Am J Psychiatry. 1971;127:1653–1658. doi: 10.1176/ajp.127.12.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevak RJ, Stoops WW, Hays LR, Rush CR. Discriminative-stimulus and subject-rated effects of methamphetamine, d-amphetamine, methylphenidate and triazolam in methamphetamine-trained humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;328:1007–1018. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.147124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoptaw S, King WD, Landstrom E, Bholat MA, Heinzerling K, Victorianne GD, Roll JM. Public Health Issues Surrounding Methamphetamine Dependence. Methamphetamine Addiction. In: Roll JR, Ling W, Rawson RA, Shoptaw S, editors. Basic Science to Treatment. Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Shoptaw S, Klausner JD, Reback CJ, Tierney S, Stansell J, Hare CB, Gibson S, Siever M, King WD, Kao U, Dang J. A public health response to the methamphetamine epidemic: The implementation of contingency management to treat methamphetamine dependence. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoptaw S, Heinzerling KG, Rotheram-Fuller E, Steward T, Wang J, Swanson AN, De La Garza R, Newton T, Ling W. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of bupropion for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:222–232. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson D, Plosker GL. Atomoxetine: a review of its use in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Drugs. 2004a;64:205–222. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson D, Plosker GL. Spotlight on atomoxetine in adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. CNS Drugs. 2004b;18:397–401. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200418060-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA. The drug abuse screening test. Addict Behav. 1982;7:363–371. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smout MF, Longo M, Harrison S, Minniti R, Wickes W, White JM. Psychosocial treatment for methamphetamine use disorders: a preliminary randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy. Subst Abus. 2010;31:98–107. doi: 10.1080/08897071003641578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofuoglu M, Poling J, Hill K, Kosten T. Atomoxetine attenuates dextroamphetamine effects in humans. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35:412–416. doi: 10.3109/00952990903383961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spealman RD. Noradrenergic involvement in the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine in squirrel monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:53–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoops WW, Blackburn JW, Hudson DA, Hays LR, Rush CR. Safety, tolerability and subject-rated effects of intranasal cocaine during atomoxetine maintenance. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;92:282–285. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. OAS Series #S-45, HHS Publication No. (SMA) Rockville, MD: 2009. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) Highlights - - 2007 National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services; p. 09-4360. [Google Scholar]

- van der Plas EA, Crone EA, van den Wildenberg WP, Tranel D, Bechara A. Executive control deficits in substance-dependent individuals: A comparison of alcohol, cocaine, and methamphetamine and of men and women. J Clinical Exp Neuropsychol. 2009;31:706–719. doi: 10.1080/13803390802484797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vocci FJ, Appel NM. Approaches to the development of medications for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Addict. 2007;102:96–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wee S, Woolverton WL. Evaluation of the reinforcing effects of atomoxetine in monkeys: Comparison to methylphenidate and desipramine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;75:271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]