Abstract

Members of the sphingosine kinase (SK) family of lipid signaling enzymes, comprising sphingosine kinase-1 and -2 (SK1, SK2) in humans, are receiving considerable attention for their roles in a number of physiological and pathophysiological processes. The SKs are considered signaling enzymes based on their production of the potent lipid second messenger sphingosine-1-phosphate, which is the ligand for a family of five G-protein linked receptors. Both SK1 and -2 are intracellular enzymes and do not possess obvious membrane anchor domains within their primary sequences. The native substrates (sphingosine and dihydrosphingosine) are lipids, as are the corresponding products, and therefore would have a propensity to be membrane associated, suggesting that specific membrane localization of the SKs could affect both access to substrate and localized production of product. Here we consider the emerging picture of the sphingosine kinases as enzymes localized to specific intracellular sites, sometimes by agonist-dependent translocation, the mechanism targeting these enzymes to those sites, and the functional consequence of that localization. Not only is the signaling output of the sphingosine kinases affected by subcellular localization, but the role of these enzymes as metabolic regulators of sphingolipid metabolism may be impacted as well.

Keywords: sphingolipid, sphingosine-1-phosphate, ceramide, lipid signaling, membrane translocation

As enzymes with hydrophobic substrates and products, it is notable that the sphingosine kinases are soluble enzymes, lacking hydrophobic membrane anchoring segments or lipid modifications that would tether them to membranes. They share this property with other lipid signaling enzymes such as the phospholipase A2s, and the phosphatidylinositol-, diacylglycerol, and ceramide-kinases. Here we will discuss how this lack of permanent membrane anchoring may provide a means for regulated targeting of the sphingosine kinases to specific intracellular sites and how this targeting may, in turn, drive selective enzymatic activation, access to specific substrate pools, and production of products at distinct locations.

There are two sphingosine kinase genes, SPHK1 and SPHK2, which generate gene products that have high sequence similarity. These gene products, SK1 and SK2, have distinctive steady-state localizations and stimulus-dependent movement to specific intracellular sites. We will therefore discuss the two sphingosine kinases separately. By and large, more is known about SK1 and therefore this will be discussed in more detail. However the unique functions of SK2 are garnering increasing interest and details of SK2 function are beginning to emerge.

The enzymology of the sphingosine kinases: 2 genes, multiple splice variants

A mammalian sphingosine kinase (SK) was first purified from rat kidney (Olivera et al. 1998) and cloned from mouse tissues (Kohama et al. 1998). These initial studies set the stage for the identification of the homologous human gene (Melendez et al. 2000;Nava et al. 2000;Pitson et al. 2000). The gene product was designated as human sphingosine kinase-1 (hSK1, gene name SPHK1). Subsequently, a second sphingosine kinase gene was identified in both mouse brain and human kidney cells that contained an extended N-terminal and an insertion of sequences in the center of the protein when compared to SK1 and this kinase was dubbed SK2 (gene name SPHK2) (Liu et al. 2000). As we discuss below, even though these isoenzymes share a high degree of polypeptide sequence similarity, studies continue to reveal profound differences in their tissue distribution, their subcellular localizations, both steady-state and stimulus-dependent, and the ways in which they are regulated.

Multiple splice variants for each isoenzyme

To date, there are three known splice variants of human SK1 and two variants of SK2 that have been functionally characterized, with the possibility of a third SK2 splice variant awaiting experimental validation (Alemany et al. 2007;Pitson 2011;Pyne et al. 2005;Shida et al. 2008). Somewhat similar splice variants for both SK1 and SK2 also exist in the mouse and rat genomes. The human SK1 splice variants are designated SK1a, SK1b and SK1c, and differ only in the length of their N-termini. [see Table 1] SK1a, which is the shortest variant, seems to be the most abundant in a variety of human tissues. When compared to SK1a, the variants SK1b and SK1c both possess longer N-termini, having an additional 14 and 86 amino acids, respectively (reviewed in (Pitson 2011). While the structural significance of having an extended N-terminal has not been exhaustively studied for these enzymes, recent work suggests that key residues in the N-terminus offer putative sites for post-translational modifications. Notably, mouse SK1b, which has an N-terminal extension of 10 amino acids as compared to mSK1a, has been shown to be palmitoylated on two cysteine residues located in the N-terminus (Kihara et al. 2005). This cysteine-dependent palmitoylation motif increased the membrane association of mSK1b. Additionally, mSK1b was more susceptible to ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation than the shorter mSK1a isoform, which was primarily localized to the cytosol. Post-translational modifications of this kind not only have the potential to alter the stability of variant SKs, they also offer possible clues in establishing subcellular localization as a distinct form of regulation for sphingosine kinases in general. The behavior of the human splice variants has not been well studied, but there is a hint that they may share similar properties (Venkataraman et al. 2006).

Table 1.

Isoforms and Enzymology of Sphingosine Kinases

| Sphingosine Kinase 1 | Sphingosine Kinase 2 | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Identification | |||

| Human | SPHK1 - 8877 | SPHK2 - 56848 |

Liu et al 2000

Pitson et al 2000 |

| Mouse | Sphk1 - 20698 | Sphk2 - 56632 |

Kohama et al 1998 Liu et al 200 |

|

| |||

| Splice Variants (accession #) | |||

| Human | SK1a (NM_001142601)+ | SK2a/short (AF245447)++ | Okada et al 2005 |

| SK1b (NM_021972)+ | SK2b/long (NM_020126)+ |

Alemany et al 2007 Pyne et al 2008 |

|

| SK1c (NM_182965)+ | SK2c (EF107108)++ | Pitson 2010 | |

| Mouse | Sphk1a (NM_001172475)+ | Sphk2 (NM_001172561)+ | Kohama et al 1998 |

| Sphk1b (NM_011451)+ | Liu et al 200 | ||

|

| |||

| Resulting Polypeptides (predicted MW+++) | |||

| Human | SK1a – 384 a.a. (42.5 kDa) | SK2a – 618 a.a. (65.2 kDa) | Igarashi et al 2003 |

| SK1b – 398 a.a. (43.9 kDa) | SK2b – 654 a.a. (69.2 kDa) |

Okada et al 2005

Alemany et al 2007 |

|

| SK1c – 470 a.a. (51.1 kDa) | SK2c – 654 a.a. (80.2 kDa) | Pitson 2010 | |

| Mouse | Sphk1a – 381 a.a. (42.3 kDa) | Sphk2a – 617 a.a (65.6 kDa) | Liu et al 2000 |

| Sphk1b – 388 a.a. (43.2 kDa) | Kihara et al 2006 | ||

|

| |||

| Substrate Specificity (reported Km ranges) | |||

| D-erythro-sphingosine (2.15 – 14 μM) |

D-erythro-sphingosine (3.4 – 14.3 μM) |

Kohama et al 1998

Olivera et al 1998 Liu et al 2000 |

|

| D-erythro-dihydrosphingosine (20 μM) |

D-erythro-dihydrosphingosine (not reported) |

Melendez et al 2000

Nava et al 2000 |

|

| FTY720 (fingolimod) (18.2 – 24.1 μM) |

Pitson et al 2000

Billich et al 2003 |

||

| D,L-threo-dihydrosphingosine Phytosphingosine |

|||

|

| |||

| Known Inhibitors* | |||

| N,N-dimethylsphingosine | N,N-dimethylsphingosine | Pitman, Pitson 2010 | |

| SKI-II | SKI-II | Tonelli et al 2010 Antoon et al 2010 |

|

| D,L-threo-dihydrosphingosine | ABC294640 | ||

|

| |||

| Abbreviations / Symbols | + – NCBI RefSeq number | +++ – ExPASy predicted MW | |

| ++ – GenBank™ number | a.a. – amino acids | ||

There is intensive research underway to identify therapeutic SK inhibitors (reviewed in Pitman et al 2010)

Although they have not been studied as extensively as the SK1 variants, the two confirmed splice variants of human sphingosine kinase 2 seem to arise from alternative start codons. Human SK2b (commonly referred to as SK2-long) has an additional 36 amino acids in the N-terminal region as compared to SK2a (also known as SK2-short) (Okada et al. 2005). [see Table 1] SK2b is expressed more abundantly than SK2a in a variety of human tissues and cultured cell lines but does not seem to be expressed in the mouse (Okada, Ding, Sonoda, Kajimoto, Haga, Khosrowbeygi, Gao, Miwa, Jahangeer, & Nakamura 2005). As with SK1, the two splice variants of SK2 are emerging as having slightly different roles in determining cell responses (Liu et al. 2003;Okada, Ding, Sonoda, Kajimoto, Haga, Khosrowbeygi, Gao, Miwa, Jahangeer, & Nakamura 2005). Future studies will be needed to determine how these variant SK2 constructs are differentially regulated.

Domain structure and function

Overall, SKs are evolutionarily highly conserved. In addition to their discovery in humans, mice and rats, SKs have been identified in such diverse species as S. cerevisiae, C. elegans, D. melanogaster, A. thaliana, and D. discoideum (Alemany, van Koppen, Danneberg, Ter, & Meyer zu 2007). Sphingosine kinases have been grouped with diacylglycerol kinases (DGKs) and ceramide kinases (CERKs) to create a novel family of lipid kinases (Wattenberg et al. 2006). Their inclusion in this family is in part due to the presence of five highly conserved domains (C1-C5) in all SK isoforms that share aspects of homology with similar domains in DGKs and CERKs. The C4 domain appears to be unique to only SKs, and this unique C4 region continues to offer insights into the mechanisms of SK function and regulation. For example, in recent years this region has been shown to contain phosphorylation sites for hSK1 at Ser225 (Pitson et al. 2003) and Thr193 (Dephoure et al. 2005), to contain multiple phosphorylation sites for hSK2 (Dephoure et al. 2008;Ding et al. 2007;Hait et al. 2007), to be involved in binding sphingosine (Yokota et al. 2004), and to include the site where calcium and integrin-binding protein 1 (CIB1) interacts with SK1 (Jarman et al. 2010)(discussed below). One site of interaction that has remained elusive is the region on SKs that binds to/interacts with acidic phospholipids. Specifically, it has been shown that phosphatidylserine (PS) and phosphatidic acid (PtOH) increase the activity of both SK1 and SK2 when added to in vitro assays (Liu, Sugiura, Nava, Edsall, Kono, Poulton, Milstien, Kohama, & Spiegel 2000;Pitson, D′Andrea, Vandeleur, Moretti, Xia, Gamble, Vadas, & Wattenberg 2000). Additionally, SK1 binds to both PS (Stahelin et al. 2005) and PtOH (Delon et al. 2004) (discussed in more detail below). Key amino acid residues for PS binding were identified in SK1 (Stahelin, Hwang, Kim, Park, Johnson, Obeid, & Cho 2005) and there was a recent report of a comparable PS binding site in hSK2 that was highly homologous to the SK1 region and could be disrupted by mutating comparable residues in each isoenzyme (Weigert et al. 2010). While this is a start, the precise binding properties and functional consequences of the interactions between SKs and acidic phospholipids need to be clarified. Considering the fact that PS and PtOH have fundamentally different roles in membrane dynamics and cell signaling, it is important to decipher the role each one plays in the regulation of sphingosine kinases.

SK1 and SK2 have structural and functional differences

Even though there are highly conserved domains in all SKs, there are fundamental structural and functional differences between human SK1 and SK2 that need to be considered here. First, hSK2 is larger than hSK1 resulting from additional regions in both the N-terminus and the central part of the sequence that combine to yield a protein that is 236 amino acids longer than hSK1 (reviewed in (Pitson 2011)). [see Table 1] The extended N-terminal region of hSK2 contains nuclear localization and export signals that are lacking in hSK1 (discussed below) (Igarashi et al. 2003). Additionally, sulfatide binding sites which are unique to hSK2 have been shown to be located in the N-terminus and are proposed to facilitate the membrane localization of hSK2 (Don and Rosen 2009). Interestingly, a caspase-1 cleavage site has recently been reported in the N-terminus of hSK2, which has the functional consequence of forming a truncated form of SK2 that can be secreted from cells during apoptosis (Weigert, Cremer, Schmidt, von, Angioni, Geisslinger, & Brune 2010). Much less is known about the functional role of the additional residues in the central part of the hSK2 sequence. In addition to being proline rich, this area of SK2 extends the proposed sphingosine-binding domain by 116 residues as compared to SK1 (reviewed in (Pitson 2011). Further research will be needed to determine if these additional residues play a role in the ability of SK2 to phosphorylate a wider array of substrates than SK1.

Substrate specificity

The main lipid substrates for both hSK1 and hSK2 are D-erythro-sphingosine and D-erythro-dihydrosphingosine. hSK1 exhibits a higher catalytic efficiency with both of these sphingolipids when compared to hSK2 (Liu, Sugiura, Nava, Edsall, Kono, Poulton, Milstien, Kohama, & Spiegel 2000;Pitson, D′Andrea, Vandeleur, Moretti, Xia, Gamble, Vadas, & Wattenberg 2000). [see Table 1] SK2 seems to have traded catalytic efficiency for a broader substrate specificity. SK2 can phosphorylate D,L-threo-dihydrosphingosine and phytosphingosine, albeit with much less efficiency than either sphingosine or dihydrosphingsoine, whereas SK1 exhibits no measurable activity with these sphingolipids (Liu, Sugiura, Nava, Edsall, Kono, Poulton, Milstien, Kohama, & Spiegel 2000). Importantly, SK2 has a much higher affinity for FTY720 (fingolimod), a sphingosine analogue, than does SK1 (Billich et al. 2003) and seems to be the main enzyme responsible for the phosphorylation of this compound. FTY720, which is currently of intense clinical interest as an immune suppressive, acts by functional antagonism of cell surface receptors for S1P, and must be phosphorylated by SK to be active.

The changeable localizations of Sphingosine Kinases 1 and 2: Impact on signaling and metabolic functions

Sphingosine kinase 1 and 2 have distinct functions and localizations. Here we will discuss the details of their localization and translocation separately, but will conclude by discussing the overall concepts that govern the role of localization of the function of these enzymes.

Sphingosine kinase-1: Localization and translocation are determined by protein and lipid interactions

Sphingosine kinase-1 is mostly a cytosolic protein in unstimulated cells but has some associations with intracellular organelles

When measured using enzymatic assays or immunoblotting, most, but not all of SK1 is found in the soluble, cytosolic fraction of cell and tissue lysates. This is true of both endogenous enzyme in cells and tissues and ectopically expressed SK1. Between 60-80% of both endogenous and ectopically expressed SK1 activity is found in the cytosol (Kohama, Olivera, Edsall, Nagiec, Dickson, & Spiegel 1998). The membrane-bound portion is very tenuously associated with the membranes and is easily washed off (our unpublished observations). A twist to this story is the identification of the mouse SK1b splice isoform. As discussed above, this isoform is palmitoylated on amino-terminal cysteines. Palmitoylation of this SK isoform appears to drive constitutive membrane association. However, this isoform has a short half-life when membrane associated which results in a low steady-state abundance of this isoform on membranes (Kihara, Anada, & Igarashi 2005). This presumably accounts for both the low measured levels of membrane associated SK activity and, potentially, the variability in which the extent of SK membrane-association has been reported, at least in mouse tissues. There is a suggestion that membrane-associated SK is localized into cholesterol/sphingomyelin-enriched microdomains (rafts) (Hengst et al. 2009). This would certainly make sense since this is where the substrate sphingosine would be expected to be concentrated, however this finding has yet to be confirmed. In tissues, total cytosolic sphingosine kinase activity, which combines SK1 and SK2 activity, ranges from a low of 30% (kidney) to almost 80% (brain and liver) (Gijsbers et al. 2001). The nature of the association with the membrane in these tissues has not been explored.

By immunofluorescence, ectopically expressed, GFP-tagged SK1 can be seen to associate with punctate structures in the perinuclear region of fibroblasts (Delon, Manifava, Wood, Thompson, Krugmann, Pyne, & Ktistakis 2004). Whether endogenous SK1 also has this distribution has yet to be determined. A striking association with centrosomes has also been noted for SK1 (and SK2) in HEK293 cells (Gillies et al. 2009). This was demonstrated both biochemically and by immunofluorescence with endogenous SK1.

Together, these data suggest that even without stimulus, SK1 has some association with intracellular structures. In addition, considering that the physiological substrate, sphingosine, is membrane associated, SK1 must at least transiently encounter sphingosine-containing membranes, although this association seems to be of sufficiently low stability that it cannot be detected by standard membrane fractionation techniques. The challenge for the future will be to demonstrate that the specific associations with these intracellular structures have functional significance.

Sphingosine kinase-1 translocates to the plasma membrane, cytoskeleton, and intracellular organelles when stimulated

Stimulation of cells with a variety of agonists leads to the translocation of SK1 to the plasma membrane (reviewed in (Wattenberg, Pitson, & Raben 2006)). In the majority of these studies the translocation appears to involve a relatively minor proportion of total SK (the exact proportion is difficult to discern because by and large quantitation is lacking). It should be noted, however, that this data is derived from studies using overexpessed SK1. Notably, however when HEK293 cells transfected with the M3 muscarinic receptor are treated with the muscarinic agonist carbachol, approximately 50% of ectopically expressed SK translocates to the plasma membrane (ter Braak et al. 2009). Translocation is very rapid, with a half-time of 3-5 seconds. In this system the plasma membrane translocation persists for hours after stimulation, but is rapidly reversed if a muscarinic antagonist is applied. This suggests that continuous signaling is required to maintain SK1 at the plasma membrane and that the retention mechanism is labile. Whether SK1 translocates to specific sites within the plasma membrane is a matter of controversy. As noted above, there is some evidence for localization to lipid rafts. In addition, Spiegel and colleagues noted a heregulin-induced translocation of SK1 to lamellipodia of melanoma cells. A PMA-induced reorganization of SK1 to the acrosomal region of sperm has also been observed (Suhaiman et al 2010).

In addition to the plasma membrane, stimulus-dependent translocation of SK1 has been observed to several other intracellular sites. Kusner and colleagues (Thompson et al. 2005) find that induction of phagocytosis in macrophages triggers a concentration of SK1 to an area around the phagosome, but not specifically to the limiting membrane of the phagosome. This localization is transient, reversing within 30 minutes. This group also reports that SK1 binds to the actin cytoskeleton in macrophages (Kusner et al. 2007), and it may be that SK1 is binding to the concentration of actin surrounding the phagosomes rather than membrane structures in this situation.

As will be discussed below, SK1 localization to membranes may involve binding to phosphatidic acid, generated from phosphatidylcholine by phospholipase D (PLD). Induction of PLD activity drives ectopically expressed SK1 to an unidentified perinuclear structure and peripheral punctate structures (Delon, Manifava, Wood, Thompson, Krugmann, Pyne, & Ktistakis 2004), which may represent the Golgi and endosomes. This localization is enhanced by the PKC activator PMA. This system utilized both overexpressed SK1 and PLD, so it is not clear whether this is a physiological site of translocation. However, considering that PLD is known to be an important regulator of Golgi function (Riebeling et al. 2009), a physiological role for PLD in translocation of SK1 to the Golgi would not be surprising.

An interesting relocalizaton of SK1 has been proposed in which SK1 is secreted outside of the cell. This goes against the dogmatic grain as SK1 does not have a signal sequence and so is not secreted through the canonical vesicular route through the secretory pathway to the plasma membrane. However, Hla and colleagues suggest there is a constitutive event which results in the extracellular generation of S1P in serum (Venkataraman, Thangada, Michaud, Oo, Ai, Lee, Wu, Parikh, Khan, Proia, & Hla 2006). In addition, the extracellular release of SK1 in microvesicles has been observed (Rigogliuso et al. 2010). SK1 has appears to be released by monocytes treated with oxidized low density lipoprotein immune complexes (Hammad et al. 2006). Ultimately, by determining the molecular mechanisms that control these release mechanisms it should be possible to test the contribution that extracellular SK makes to the generation of extracellular S1P.

The membrane translocation of SK1 involves interaction with acidic phospholipids, SK1 binding proteins, and phosphorylation of SK1

Role of Lipids in Translocation

Acidic phospholipids mediate the binding of SK1 to membranes. Both phosphatidylserine (PS) and phosphatidic acid (PtOH) enhance SK1 enzymatic activity in mixed micelle and liposome-based cell-free assays (Pitson, D′Andrea, Vandeleur, Moretti, Xia, Gamble, Vadas, & Wattenberg 2000;Stahelin, Hwang, Kim, Park, Johnson, Obeid, & Cho 2005). However which of these lipids is a driver of SK1 membrane association in cells is not yet clear. Stahelin and colleagues find that recombinant SK1 binding to artificial membranes is dependent on PS content (Stahelin, Hwang, Kim, Park, Johnson, Obeid, & Cho 2005). Surprisingly PtOH does not enhance binding. This contrasts with lipid binding studies by Ktistakis’ group (Delon, Manifava, Wood, Thompson, Krugmann, Pyne, & Ktistakis 2004). They find that SK1 binds strongly to PtOH bound to beads. They indirectly tested PS binding by looking for competition of PS for SK1 binding to bead-immobilized PtOH, and did not detect a role for PS by this measure. This group also elegantly demonstrated that the generation of PtOH in biological membranes drives SK1 membrane association in a cell-free system. The resolution of the apparently divergent findings on PS versus PtOH function could be attributed to the methodologies used. This is, however, unsatisfying in addressing the physiological role of these lipids. It is critically important to understand which lipids drive SK1 membrane association in a biological setting because this would determine the temporal and spatial activation of SK1 signaling and metabolic functions. It may well be that both lipids have roles under different conditions. PS is relatively abundant on the inner surface of the plasma membrane and therefore may serve as a constitutive platform for the binding of SK1 when other required activation steps have been triggered. PtOH is transiently produced by the actions of PLD and diacylglycerol kinases. Therefore the production of PtOH may more precisely control the timing of SK1 translocation at specific sites of PLD activation.

Role of SK1 Phosphorylation in Membrane Translocation

Phosphorylation of SK1 at Serine225 (S225 in the human sequence) is required for SK1 translocation under many, but not all, conditions (reviewed in (Wattenberg, Pitson, & Raben 2006)). Mutation of S225 to alanine blocks translocation of SK1 to the plasma membrane in response to activation of the MAP kinase pathway (Pitson, Moretti, Zebol, Lynn, Xia, Vadas, & Wattenberg 2003). How does this phosphorylation lead to translocation? Phosphorylation at S225 is required for the PS-mediated binding of SK to artificial membranes detected by Stahelin et al (Stahelin, Hwang, Kim, Park, Johnson, Obeid, & Cho 2005), indicating that a conformational change induced by phosphorylation of SK1 exposes a lipid binding domain. It is unknown whether the binding to PtOH also requires S225 phosphorylation. This is an important gap in our understanding.

Not all membrane translocation of SK1 requires S225 phosphorylation. The localization of SK1 to nascent phagosomes is independent of S225 phosphorylation (Thompson, Iyer, Melrose, VanOosten, Johnson, Pitson, Obeid, & Kusner 2005). Another clear example is the robust translocation of SK1 induced by muscarinic receptor activation (ter Braak, Danneberg, Lichte, Liphardt, Ktistakis, Pitson, Hla, Jakobs, & Heringdorf 2009). This is mediated by the Gq G-protein. However, the downstream pathway that triggers SK1 translocation in this system remains a mystery. Two downstream effectors of Gq, protein kinase C (PKC) and elevated calcium, were ruled out as important mediators of translocation of SK1. Similarly activation of phospholipase D does not seem to be involved. One possibility is that an effector downstream of Gq mediates a conformational change in SK1 which exposes a PS-binding site.

SK1 protein binding partners involved in translocation

SK1 was initially identified as a calmodulin binding protein (Olivera, Kohama, Tu, Milstien, & Spiegel 1998;Pitson, D′Andrea, Vandeleur, Moretti, Xia, Gamble, Vadas, & Wattenberg 2000;Sutherland et al. 2006). However the actual binding partner is not calmodulin itself, but a closely related family member, Calcium and Integrin-binding Protein-1 (CIB1) (Jarman, Moretti, Zebol, & Pitson 2010). CIB1 binds to a specific calmodulin binding site in SK1 (Sutherland, Moretti, Hewitt, Bagley, Vadas, & Pitson 2006) and is required for PMA-stimulated, S225 phosphorylation-dependent, translocation of SK1 to the plasma membrane. In contrast to Gq-mediated translocation, PMA-induced translocation requires calcium (Jarman, Moretti, Zebol, & Pitson 2010). This calcium appears to be required for the binding of C1B1 to the plasma membrane mediated by exposure of a covalently bound, amino-terminal myristic acid. Binding of CIB1 to SK1 does not depend on S225 phosphorylation, so the details of this dependence have yet to be worked out. Pitson and colleagues suggest that the calcium-mediated binding of CIB1 to the plasma membrane may initially target SK1 to that site and that S225 phosphorylation may retain it there by enabling the binding of SK1 to PS (Jarman, Moretti, Zebol, & Pitson 2010).

Traf2, a downstream effector of the TNFα receptor, is also a binding partner for SK1 (Xia et al. 2002). It is possible that Traf2 bound to the TNFα receptor mediates a degree of SK1 translocation to the plasma membrane. This has yet to be directly tested.

Sphingosine kinase-2 shuttles between the cytosol and the nucleus

There has been considerable confusion about the subcellular localization of SK2. Initially, based on overexpressions studies, SK2 was reported as predominantly a soluble, cytoplasmic protein (Liu, Sugiura, Nava, Edsall, Kono, Poulton, Milstien, Kohama, & Spiegel 2000). The overexpressed protein was also reported to be associated with the endoplasmic reticulum in a serum-dependent manner (Maceyka et al. 2005). However, ectopically-expressed SK2 was also reported to be a nuclear protein (Igarashi, Okada, Hayashi, Fujita, Jahangeer, & Nakamura 2003;Okada, Ding, Sonoda, Kajimoto, Haga, Khosrowbeygi, Gao, Miwa, Jahangeer, & Nakamura 2005). Both nuclear import (Igarashi, Okada, Hayashi, Fujita, Jahangeer, & Nakamura 2003) and nuclear export signals (Ding, Sonoda, Yu, Kajimoto, Goparaju, Jahangeer, Okada, & Nakamura 2007) have been identified in the SK2 sequence. More recent studies in which the endogenous protein was examined have determined that SK2 is, indeed, found in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm and shuttles between these two sites (Ding, Sonoda, Yu, Kajimoto, Goparaju, Jahangeer, Okada, & Nakamura 2007;Hait et al. 2009;Sankala et al. 2007). The steady-state distribution of SK2 between cytosol and nucleus seems to depend on both the cell type and culture conditions. In some cells, such as the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line, the nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio is very high (Sankala, Hait, Paugh, Shida, Lepine, Elmore, Dent, Milstien, & Spiegel 2007). Regulation of the nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio is accomplished by modulating the activity of the nuclear export signal (NES) by phosphorylation. Phosphorylation of the NES nuclear export of SK2 and therefore decreases the nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio (Ding, Sonoda, Yu, Kajimoto, Goparaju, Jahangeer, Okada, & Nakamura 2007).

Recently Brune and colleagues reported that SK2 can be released from apoptotic cells by a caspase mediated cleavage at the amino-terminus (Weigert, Cremer, Schmidt, von, Angioni, Geisslinger, & Brune 2010). They find that this release is coupled to the PS binding properties of SK2. They suggest that the externalization of PS during apoptosis facilitates the flipping of SK2 onto the extracytoplasmic face of the plasma membrane.

Spiegel and colleagues have observed that SK2 is also found in the mitochondrial matrix (Strub et al. 2011).This is a provocative assertion, which rests most directly on fractionation data of endogenous SK2 from heart tissue. This will be an extremely interesting story to follow as it is developed.

The function of sphingosine kinase localization and translocation to specific sites: S1P secretion, S1P delivery to intracellular effectors, access to substrate and SK modulation of sphingolipid metabolism

Secretion of S1P

One potential role of SK1 translocation to the plasma membrane is to enhance the secretion of S1P outside of the cell. There has been a spirited discussion about the relative contributions of intracellular versus extracellular S1P towards the biological effects of SK activity (reviewed in (Strub et al. 2010). The identification of G-protein linked receptors for which S1P is a potent ligand (reviewed in (Rosen et al. 2009;Strub, Maceyka, Hait, Milstien, & Spiegel 2010) clarified the extracellular role of S1P. Since SK is a cytosolic protein (with the possible exception of SK released outside the cell as discussed above) S1P must be exported from the cell to reach the extracellular milieu . The identification of the S1P plasma membrane transporter is somewhat controversial. Several members of the ABC transporter family have been implicated in S1P secretion (reviewed in (Kim et al. 2009)). A novel transporter, Spns2 (Hisano et al. 2011;Kawahara et al. 2009) also has been demonstrated to be an S1P transporter. Work still needs to be done to establish the relative importance of these two transport systems. The ABC transporters are relatively promiscuous with respect to their transport substrates, so it would not be surprising if members of the ABC transporter family export S1P when levels of the more specific S1P transporter, Spns2, are low.

Translocation of SK1 to the plasma membrane does indeed lead to enhanced secretion of S1P (Johnson et al. 2002;Pitson, Moretti, Zebol, Lynn, Xia, Vadas, & Wattenberg 2003). The enhanced secretion is relatively modest, increasing the proportion of S1P secreted from the cell by approximately 3-fold. However, translocation of SK1 in these systems is only partial. Therefore the portion of SK1 that does translocate to the plasma membrane is considerably more active than cytosolic SK1 in promoting S1P secretion.

S1P delivery to Specific Effectors

As more details are established about intracellular effectors of S1P action, the notion has emerged that SK may be targeted in proximity to those effectors. For example, S1P is an essential cofactor for the ubiquitin ligase activity of Traf2 (Alvarez et al. 2010). Since SK1 binds to Traf2 (Xia, Wang, Moretti, Albanese, Chai, Pitson, D′Andrea, Gamble, & Vadas 2002), it seems reasonable to presume that the interaction SK1 with Traf2 ensures that S1P is generated close to its target. This raises a number of interesting questions, the most important of which is why it is necessary to generate a high local concentration of S1P to satisfy the binding requirements of Traf2? Below we will discuss the movement of S1P in cells and the implications for delivery to intracellular effectors and downstream S1P metabolic enzymes.

The recent identification of S1P as a negative regulator of histone deacetylases 1 and 2 (HDAC1 and 2) rationalizes the nuclear localization of SK2 (Hait, Allegood, Maceyka, Strub, Harikumar, Singh, Luo, Marmorstein, Kordula, Milstien, & Spiegel 2009). Furthermore, in these studies SK2 was found to associate with the histones themselves, bringing SK2 into close association with the HDACs. It will be fascinating to see if this association is regulated to fine-tune histone deacetylation under specific conditions.

The localization of SK to regions of the forming phagosomes in macrophages may be related to the ability of S1P to induce release of calcium from intracellular stores (Ghosh et al. 1990;Ghosh et al. 1994). Indeed Mycobacterium tuberculosis inhibits phagocytosis by inhibiting sphingosine kinase activity (Thompson, Iyer, Melrose, VanOosten, Johnson, Pitson, Obeid, & Kusner 2005). In this case localized release of calcium may be required for phagosome formation. Perhaps the generation of S1P in proximity to elements of the endoplasmic reticulum near the forming phagosome generates a localized elevation of calcium required for the process.

The observation that SK1 is localized to membrane ruffles at the leading edge of migrating cells may be connected to activation of the p21-activated protein kinase 1 (PAK1) a downstream effector of Rac and CDC24, which have well known roles in cytoskeletal rearrangements. S1P activates PAK1 in vitro at micromolar S1P levels (Maceyka et al. 2008). The physiological relevance of this activation has yet to be confirmed. However, because a high concentration of S1P is required for activation of PAK1, localized production of S1P may be required to drive S1P-dependent PAK1 activation.

Access of SK to Sphingosine

Early studies of partially purified SK demonstrated that SK observes surface dilution kinetics, meaning that enzyme activity is sensitive to the concentration of sphingosine within the membrane that it encounters rather than on the bulk concentration of substrate (Buehrer and Bell 1992). The implication is that when SK contacts a membrane surface it resides there for a considerable length of time searching for substrate. Consequently, SK localization relative to the concentration of sphingosine at a particular membrane site may have a profound effect on S1P production. Unfortunately there is a paucity of data on the distribution of sphingosine within the cell. Sphingosine is produced solely through ceramide degradation by one of several ceramidases. Acid ceramidase is a lysosomal enzyme, neutral ceramidase is found at the plasma membrane, and the alkaline ceramidases are localized to the Golgi apparatus and the endoplasmic reticulum (reviewed in (Mao and Obeid 2008)). In the absence of further transport of sphingosine, these might be expected to be the sites of sphingosine concentration. However based on its physical-chemical properties, sphingosine should transfer fairly easily between membranes through the aqueous phase (Garmy et al. 2005b). This would suggest that regardless of where it is generated, sphingosine would redistribute to diverse intracellular membranes and be accessible to SK at many sites. However, there is indirect evidence that sphingosine is compartmentalized. When sphingosine is added externally to the cell, despite its rapid uptake it cannot be used directly for ceramide synthesis, which takes place in the ER (reviewed in (Stiban et al. 2010)). Instead, externally added sphingosine has to be activated by the combined action of SK and an S1P phosphatase. This activation might involve transport of sphingosine from the plasma membrane pool to the ER pool, although direct evidence is lacking. Further complicating the issue of access of SK to sphingosine is the fact that sphingosine interacts with cholesterol and therefore its chemical activity as a substrate may depend on the lipid composition of the membrane in which it is found (Garmy et al. 2005a). Consequently, while it is likely that SK localization to specific sites may dictate access to sphingosine, this has yet to be definitively established and is an important area for further study.

Access of SK to dihydrosphingosine and consequences of SK localization for sphingolipid metabolism

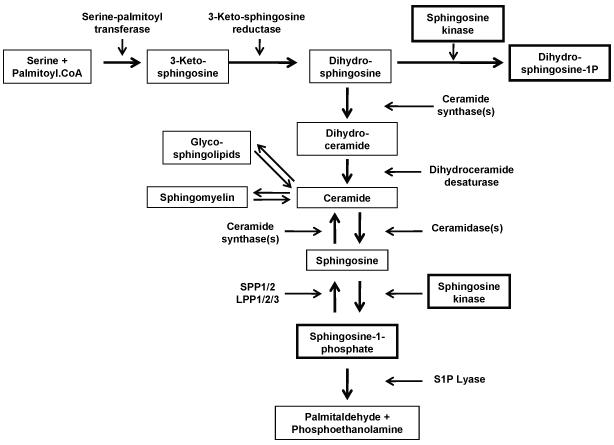

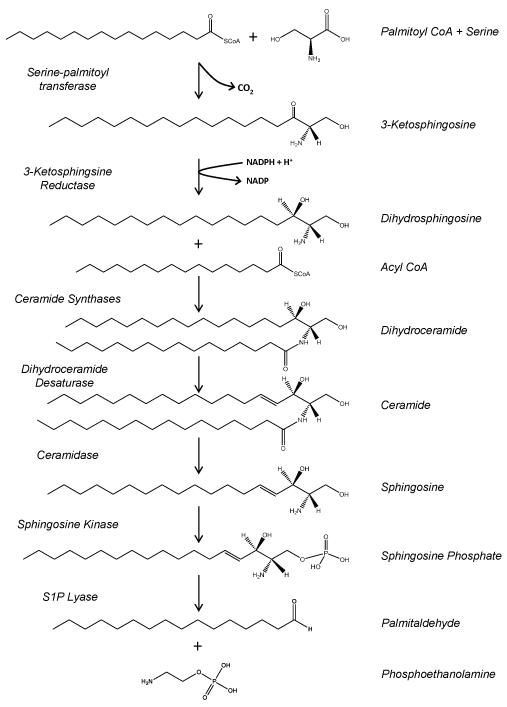

SK localization has been shown to affect access to an alternate substrate, dihydrosphingosine. Dihydrosphingosine is produced by the de novo pathway of ceramide biosynthesis, via the concerted action of serine palmitoyl transferase and 3-ketosphingosine reductase (Figure 1). When cellular sphingosine kinase is elevated, high levels of dihydrosphingosine-1-phosphate (DHS1P) are produced (Berdyshev et al. 2006;Siow et al. 2010). This increase in DHS1P is produced by either cytosolic SK1 or SK1 artificially anchored to the ER. However, SK targeted to the plasma membrane does not produce DHS1P (Siow, Anderson, Berdyshev, Skobeleva, Pitson, & Wattenberg 2010). This result is understandable because the enzymes producing dihydrosphingosine are localized to the ER (Mandon et al. 1992). Steady state levels of dihydrosphingosine are extremely low (Berdyshev, Gorshkova, Usatyuk, Zhao, Saatian, Hubbard, & Natarajan 2006;Siow, Anderson, Berdyshev, Skobeleva, Pitson, & Wattenberg 2010), indicating that under normal circumstances dihydrosphingosine is efficiently utilized by the ceramide synthases, which are also in the ER (Reviewed in (Stiban, Tidhar, & Futerman 2010)) and probably does not have time to redistribute to non-ER membranes. Therefore, only when SK has access to the ER can dihydrosphingosine be utilized as a substrate. The regulated generation of DHS1P could have two important consequences. First, S1P and DHS1P have distinct biological profiles and so the balance between SK access to sphingosine and dihydrosphingosine could affect SK signaling (Bu et al. 2005;Bu et al. 2008). Possibly more importantly, the diversion of dihydrosphingosine from the ceramide biosynthetic pathway by SK may modulate ceramide biosynthesis (Figure 1). Indeed, depletion of SK1 results in elevated ceramide levels (Siow, Anderson, Berdyshev, Skobeleva, Pitson, & Wattenberg 2010;Taha et al. 2005). The idea that SK, by consuming sphingosine and dihydrosphingosine, can modulate ceramide levels is attractive. It is notable that by producing S1P and DHS1P SK provides the substrates for the S1P lyase, the only cellular enzyme that can degrade the sphingosine backbone (Figure 1). Theoretically, this places SK at a key juncture in sphingolipid metabolism. It should be kept in mind that steady state levels of S1P are minor compared to levels of ceramide (for examples see (Berdyshev, Gorshkova, Usatyuk, Zhao, Saatian, Hubbard, & Natarajan 2006;Siow, Anderson, Berdyshev, Skobeleva, Pitson, & Wattenberg 2010)). However the flux of sphingosine/dihydrosphingosine through this pathway has yet to be measured and while the steady state levels of S1P/DHS1P may be relatively low, the rate of flux through them may be sufficient to have a significant role on the production of ceramide by the de novo and salvage pathways.

Figure 1.

(Modified from Siow et al, 2011. Adv. Enzyme Reg. and Wattenberg 2011. World J. Biochem). A. Sphingolipid metabolism. Note that the de novo biosynthesis of sphingolipids begins with the condensation of serine and palmitoyl CoA and that the sole enzyme that can accomplish the degradation of the sphingosine backbone is S1P lyase. Note also that sphingosine kinase can utilize dihydrosphingosine generated during de novo sphingolipid synthesis or sphingosine released from ceramide by ceramidases. B. Structures of sphingolipid intermediates. Note that the double 4,5 double bond in sphingosine is only introduced in the context of dihydroceramide. Therefore all dihydrosphingosine-1-phosphate must be derived from dihydrosphingosine diverted from ceramide biosynthesis.

It might be expected that localization of SK would affect the downstream metabolism of S1P (Figure 1). S1P is dephosphorylated by two S1P-specific phosphatases (SPP1-2) and, potentially, three less specific lipid phosphatases (LPP1-3) (Le Stunff et al. 2002;Ogawa et al. 2003;Pyne and Pyne 2002). The SPPs are localized to the ER whereas the LPPs are localized both to the ER and the PM. S1P lyase, the only cellular enzyme that can irreversibly degrade the sphingosine backbone, is also localized to the ER (Ikeda et al. 2004;Reiss et al. 2003). Surprisingly, however, regardless of whether the site of S1P production is at the ER or the PM, the rates of degradation of S1P by these enzymes is the same (Siow, Anderson, Berdyshev, Skobeleva, Pitson, & Wattenberg 2010). The most obvious explanation for this observation is that S1P is rapidly transported throughout the cell. This is supported directly by pulse labeling experiments followed by subcellular fractionation (Siow, Anderson, Berdyshev, Skobeleva, Pitson, & Wattenberg 2010). The mechanism of intracellular movement of S1P is unknown. S1P may move by diffusion through the aqueous space from membrane to membrane or S1P may, like many other lipids, be transported by a specific protein-mediated process. The concept that S1P rapidly moves between membranes is puzzling in light of the suggestions noted above that SK is localized in proximity to certain effectors. One possibility is that flow of S1P is facile between the PM and ER but there are other, less accessible sites within the cell. One obvious example is that S1P may not have access from the cytosol to the nucleus, thus necessitating the localization of SK2 to the nucleus to supply S1P to nuclear effectors.

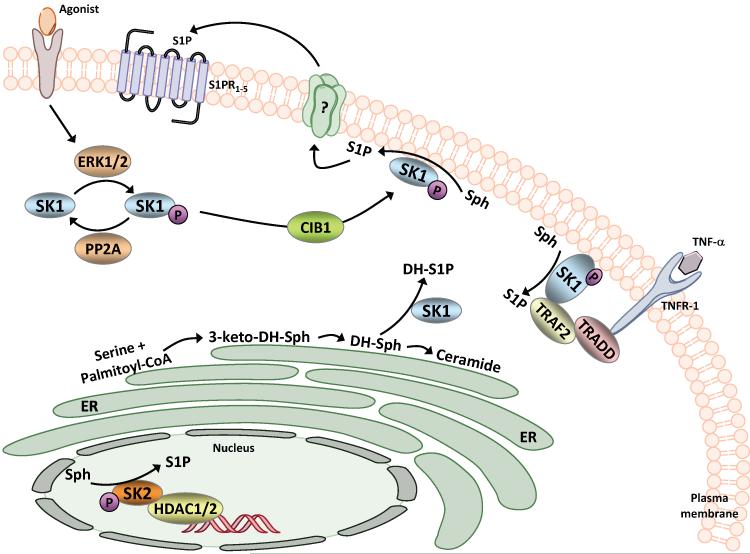

Summary and Directions for the Future

SK1 and SK2 are membrane active, but soluble enzymes, and clearly can have distinct, and changeable, sites of intracellular concentration. Both the substrates and products of the SKs are lipids and it is to be expected that localizing the SKs to a particular site will impact on the utilization of substrate and the localized production of product (Figure 2). Localization can determine access of SKs to sphingosine and dihydrosphingosine, and can therefore affect both the level and the type of signaling lipid product that is produced. Since dihydrosphingosine and sphingosine are the precursors of ceramide synthesis through the de novo and salvage pathways respectively, regulation of SK access to these substrates could also affect levels of ceramide and downstream ceramide metabolites such as sphingomyelin and glycosphingolipids (Figure 2). There are hints that SK localization may be used to load specific downstream S1P effectors with S1P in a spacially restricted way. SK translocation to the plasma membrane seems to enhance the secretion of S1P to the extracellular milieu where it can encounter members of the S1P receptor family and therefore may have a profound effect on autocrine and paracrine signaling function. Surprisingly, the site of S1P production seems to have a limited effect on the degradation of S1P, despite the fact that the enzymes of degradation are, for the most part, localized to the endoplasmic reticulum. This suggests that there is a robust mechanism for redistributing S1P throughout the cell. Establishing the mechanism and routes of intracellular S1P movement will be important for tying together SK localization and S1P signaling function.

Figure 2.

A model of the role of sphingosine kinase localization on substrate utilization and delivery of S1P to specific sites for secretion or loading of intracellular effectors. During agonist stimulation SK1 is phosphorylated by ERK1/2, or a related kinase, resulting in translocation to the plasma membrane (PM). This translocation is mediated by the CIB1 protein and binding to acidic phospholipids. Translocation to the PM enhances secretion of S1P, and ultimately S1P binds to a member of the S1P receptor (S1PR) family. Additionally, SK1 binds in part to TRAF2 and this may load S1P onto TRAF2 to activate the ubiquitin ligase activity of TRAF2. Similarly, the nuclear localization of SK2 is essential for its binding to histones, which may optimize the loading of S1P onto histone deacetylases-1 or -2 (HDAC1/2) and the subsequent inhibition of histone deacetylase activity. Membrane binding of SK1 may specify whether the lipid substrate is sphingosine (Sph) (plasma membrane) or dihydrosphingosine (DH-Sph)(endoplasmic reticulum, ER). Localization of SK1 at the ER diverts dihydrosphingosine from the ceramide biosynthetic pathway. (Note: A color version of this figure is available online).

Studies to localize the SKs have relied heavily on immunofluorescence and, to a limited extent, on subcellular fractionation. These techniques, while informative, may be missing important, but more transient, associations of SKs with specific membrane sites. More sophisticated fluorescent techniques such as FRET and correlation spectroscopy will be required to detect such interactions. The mechanisms governing localization of SKs to specific sites are still being uncovered. Understanding these mechanisms in detail will provide the necessary tools for determining the regulation of SK localization during cellular responses and generate the means to experimentally test the role of SK localization in signaling and metabolism of sphingolipids.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Dan Raben, Mr. Charles Anderson, and Mr. Mitterand Massa for helpful discussions.

Declaration of Interest This work was supported by NIH R01CA111987 (to BW) and a Brown Cancer Center Fellowship (to DS).

References

- Alemany R, van Koppen CJ, Danneberg K, Ter BM, Meyer zu HD. Regulation and functional roles of sphingosine kinases. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch.Pharmacol. 2007;374(5-6):413–428. doi: 10.1007/s00210-007-0132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez SE, Harikumar KB, Hait NC, Allegood J, Strub GM, Kim EY, Maceyka M, Jiang H, Luo C, Kordula T, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate is a missing cofactor for the E3 ubiquitin ligase TRAF2. Nature. 2010;465(7301):1084–1088. doi: 10.1038/nature09128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdyshev EV, Gorshkova IA, Usatyuk P, Zhao Y, Saatian B, Hubbard W, Natarajan V. De novo biosynthesis of dihydrosphingosine-1-phosphate by sphingosine kinase 1 in mammalian cells. Cellular Signalling. 2006;18(10):1779–1792. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billich A, Bornancin F, Devay P, Mechtcheriakova D, Urtz N, Baumruker T. Phosphorylation of the Immunomodulatory Drug FTY720 by Sphingosine Kinases. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(48):47408–47415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307687200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu S, Kapanadze B, Hsu T, Trojanowska M. Opposite effects of dihydrosphingosine 1-phosphate and sphingosine 1-phosphate on transforming growth factor-beta/Smad signaling are mediated through the PTEN/PPM1A-dependent pathway. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(28):19593–19602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802417200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu S, Yamanaka M, Pei H, Bielawska A, Bielawski J, Hannun YA, Obeid L, Trojanowska M. Dihydrosphingosine 1-phosphate stimulates MMP1 gene expression via activation of ERK1/2-Ets1 pathway in human fibroblasts. FASEB J. 2005;20(1):184–6. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4646fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buehrer BM, Bell RM. Inhibition of sphingosine kinase in vitro and in platelets. Implications for signal transduction pathways. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267(5):3154–3159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delon C, Manifava M, Wood E, Thompson D, Krugmann S, Pyne S, Ktistakis NT. Sphingosine Kinase 1 Is an Intracellular Effector of Phosphatidic Acid. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(43):44763–44774. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405771200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dephoure N, Howson RW, Blethrow JD, Shokat KM, O′Shea EK. Combining chemical genetics and proteomics to identify protein kinase substrates. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2005;102(50):17940–17945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509080102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dephoure N, Zhou C, Villen J, Beausoleil SA, Bakalarski CE, Elledge SJ, Gygi SP. A quantitative atlas of mitotic phosphorylation. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2008;105(31):10762–10767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805139105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding G, Sonoda H, Yu H, Kajimoto T, Goparaju SK, Jahangeer S, Okada T, Nakamura S. Protein kinase D-mediated phosphorylation and nuclear export of sphingosine kinase 2. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(37):27493–27502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701641200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Don AS, Rosen H. A lipid binding domain in sphingosine kinase 2. Biochem.Biophys.Res.Commun. 2009;380(1):87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garmy N, Taieb N, Yahi N, Fantini J. Interaction of cholesterol with sphingosine: physicochemical characterization and impact on intestinal absorption. Journal of Lipid Research. 2005a;46(1):36–45. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400199-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garmy N, TaIeb N, Yahi N, Fantini J. Apical uptake and transepithelial transport of sphingosine monomers through intact human intestinal epithelial cells: Physicochemical and molecular modeling studies. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2005b;440(1):91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh TK, Bian J, Gill DL. Intracellular calcium release mediated by sphingosine derivatives generated in cells. Science. 1990;248(4963):1653–1656. doi: 10.1126/science.2163543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh TK, Bian J, Gill DL. Sphingosine 1-phosphate generated in the endoplasmic reticulum membrane activates release of stored calcium. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269(36):22628–22635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gijsbers S, Van der Hoeven G, Van Veldhoven PP. Subcellular study of sphingoid base phosphorylation in rat tissues: evidence for multiple sphingosine kinases. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 2001;1532(1-2):37–50. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(01)00111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillies L, Lee SC, Long JS, Ktistakis N, Pyne NJ, Pyne S. The sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 5 and sphingosine kinases 1 and 2 are localised in centrosomes: possible role in regulating cell division. Cell Signal. 2009;21(5):675–684. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hait NC, Bellamy A, Milstien S, Kordula T, Spiegel S. Sphingosine kinase type 2 activation by ERK-mediated phosphorylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(16):12058–12065. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609559200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hait NC, Allegood J, Maceyka M, Strub GM, Harikumar KB, Singh SK, Luo C, Marmorstein R, Kordula T, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Regulation of Histone Acetylation in the Nucleus by Sphingosine-1-Phosphate. Science. 2009;325(5945):1254–1257. doi: 10.1126/science.1176709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammad SM, Taha TA, Nareika A, Johnson KR, Lopes-Virella MF, Obeid LM. Oxidized LDL immune complexes induce release of sphingosine kinase in human U937 monocytic cells. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2006;79(1-2):126–140. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengst JA, Guilford JM, Fox TE, Wang X, Conroy EJ, Yun JK. Sphingosine kinase 1 localized to the plasma membrane lipid raft microdomain overcomes serum deprivation induced growth inhibition. Arch.Biochem.Biophys. 2009;492(1-2):62–73. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisano Y, Kobayashi N, Kawahara A, Yamaguchi A, Nishi T. The sphingosine 1-phosphate transporter, SPNS2, functions as a transporter of the phosphorylated form of the immunomodulating agent FTY720. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286(3):1758–1766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.171116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi N, Okada T, Hayashi S, Fujita T, Jahangeer S, Nakamura S.i. Sphingosine Kinase 2 Is a Nuclear Protein and Inhibits DNA Synthesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(47):46832–46839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306577200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda M, Kihara A, Igarashi Y. Sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase SPL is an endoplasmic reticulum-resident, integral membrane protein with the pyridoxal 5′-phosphate binding domain exposed to the cytosol. Biochem.Biophys.Res Commun. 2004;325(1):338–343. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarman KE, Moretti PA, Zebol JR, Pitson SM. Translocation of sphingosine kinase 1 to the plasma membrane is mediated by calcium- and integrin-binding protein 1. J Biol.Chem. 2010;285(1):483–492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.068395. available from: PM:19854831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KR, Becker KP, Facchinetti MM, Hannun YA, Obeid LM. PKC-dependent activation of sphingosine kinase 1 and translocation to the plasma membrane. Extracellular release of sphingosine-1-phosphate induced by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(38):35257–35262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203033200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara A, Nishi T, Hisano Y, Fukui H, Yamaguchi A, Mochizuki N. The Sphingolipid Transporter Spns2 Functions in Migration of Zebrafish Myocardial Precursors. Science. 2009;323(5913):524–527. doi: 10.1126/science.1167449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihara A, Anada Y, Igarashi Y. Mouse sphingosine kinase isoforms SPHK1a and SPHK1b differ in enzymatic traits including stability, localization, modification, and oligomerization. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;281(7):4532–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510308200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim RH, Takabe K, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Export and functions of sphingosine-1-phosphate. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 2009;1791(7):692–696. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohama T, Olivera A, Edsall L, Nagiec MM, Dickson R, Spiegel S. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of murine sphingosine kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(37):23722–23728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.23722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusner DJ, Thompson CR, Melrose NA, Pitson SM, Obeid LM, Iyer SS. The Localization and Activity of Sphingosine Kinase 1 Are Coordinately Regulated with Actin Cytoskeletal Dynamics in Macrophages. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(32):23147–23162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700193200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Stunff H, Peterson C, Liu H, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate and lipid phosphohydrolases. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 2002;1582(1-3):8–17. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Sugiura M, Nava VE, Edsall LC, Kono K, Poulton S, Milstien S, Kohama T, Spiegel S. Molecular Cloning and Functional Characterization of a Novel Mammalian Sphingosine Kinase Type 2 Isoform. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(26):19513–19520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002759200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Toman RE, Goparaju SK, Maceyka M, Nava VE, Sankala H, Payne SG, Bektas M, Ishii I, Chun J, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Sphingosine Kinase Type 2 Is a Putative BH3-only Protein That Induces Apoptosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(41):40330–40336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304455200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maceyka M, Alvarez SE, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Filamin A links sphingosine kinase 1 and sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 at lamellipodia to orchestrate cell migration. Mol.Cell Biol. 2008;28(18):5687–5697. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00465-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maceyka M, Sankala H, Hait NC, Le Stunff H, Liu H, Toman R, Collier C, Zhang M, Satin LS, Merrill AH, Jr., Milstien S, Spiegel S. SphK1 and SphK2, Sphingosine Kinase Isoenzymes with Opposing Functions in Sphingolipid Metabolism. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(44):37118–37129. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandon EC, Ehses I, Rother J, van Echten G, Sandhoff K. Subcellular localization and membrane topology of serine palmitoyltransferase, 3-dehydrosphinganine reductase, and sphinganine N- acyltransferase in mouse liver. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267(16):11144–11148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao C, Obeid LM. Ceramidases: regulators of cellular responses mediated by ceramide, sphingosine, and sphingosine-1-phosphate. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 2008;1781(9):424–434. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melendez AJ, Carlos-Dias E, Gosink M, Allen JM, Takacs L. Human sphingosine kinase: molecular cloning, functional characterization and tissue distribution. Gene. 2000;251(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00205-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nava VE, Lacana′ E, Poulton S, Liu H, Sugiura M, Kono K, Milstien S, Kohama T, Spiegel S. Functional characterization of human sphingosine kinase-1. FEBS Letters. 2000;473(1):81–84. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01510-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa C, Kihara A, Gokoh M, Igarashi Y. Identification and characterization of a novel human sphingosine-1-phosphate phosphohydrolase, hSPP2. J Biol.Chem. 2003;278(2):1268–1272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209514200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T, Ding G, Sonoda H, Kajimoto T, Haga Y, Khosrowbeygi A, Gao S, Miwa N, Jahangeer S, Nakamura S.i. Involvement of N-terminal-extended Form of Sphingosine Kinase 2 in Serum-dependent Regulation of Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(43):36318–36325. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504507200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivera A, Kohama T, Tu Z, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Purification and characterization of rat kidney sphingosine kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(20):12576–12583. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitson SM. Regulation of sphingosine kinase and sphingolipid signaling. Trends Biochem.Sci. 2011;36(2):97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitson SM, D′Andrea RJ, Vandeleur L, Moretti PA, Xia P, Gamble JR, Vadas MA, Wattenberg BW. Human sphingosine kinase: purification, molecular cloning and characterization of the native and recombinant enzymes. Biochem.J. 2000;350(Pt 2):429–41. 429-441. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitson SM, Moretti PAB, Zebol JR, Lynn HE, Xia P, Vadas MA, Wattenberg BW. Activation of sphingosine kinase 1 by ERK1/2-mediated phosphorylation. The EMBO Journal. 2003;22(20):5491–5500. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyne S, Long JS, Ktistakis NT, Pyne NJ. Lipid phosphate phosphatases and lipid phosphate signalling. Biochem.Soc.Trans. 2005;33(Pt 6):1370–1374. doi: 10.1042/BST0331370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyne S, Pyne NJ. Sphingosine 1-phosphate signalling and termination at lipid phosphate receptors. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 2002;1582(1-3):121–131. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss U, Oskouian B, Zhou J, Gupta V, Sooriyakumaran P, Kelly S, Wang E, Alfred H, Saba JD. Sphingosine phosphate lyase enhances stress-induced ceramide generation and apoptosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;279(2):1281–1290. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riebeling C, Morris AJ, Shields D. Phospholipase D in the Golgi apparatus. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 2009;1791(9):876–880. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigogliuso S, Donati C, Cassara D, Taverna S, Salamone M, Bruni P, Vittorelli ML. An active form of sphingosine kinase-1 is released in the extracellular medium as component of membrane vesicles shed by two human tumor cell lines. J.Oncol. 2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/509329. 2010:509329. Epub@2010 May 24., 509329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen H, Gonzalez-Cabrera PJ, Sanna MG, Brown S. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor signaling. Annu.Rev.Biochem. 2009;78:743–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.072407.103733. 743-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankala HM, Hait NC, Paugh SW, Shida D, Lepine S, Elmore LW, Dent P, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Involvement of sphingosine kinase 2 in p53-independent induction of p21 by the chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin. Cancer Res. 2007;67(21):10466–10474. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shida D, Takabe K, Kapitonov D, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Targeting SphK1 as a new strategy against cancer. Curr.Drug Targets. 2008;9(8):662–673. doi: 10.2174/138945008785132402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siow DL, Anderson CD, Berdyshev EV, Skobeleva A, Pitson SM, Wattenberg BW. Intracellular localization of sphingosine kinase 1 alters access to substrate pools but does not affect the degradative fate of sphingosine-1-phosphate. Journal of Lipid Research. 2010;51(9):2546–2559. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M004374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahelin RV, Hwang JH, Kim JH, Park ZY, Johnson KR, Obeid LM, Cho W. The mechanism of membrane targeting of human sphingosine kinase 1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(52):43030–43038. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507574200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiban J, Tidhar R, Futerman AH. Ceramide synthases: roles in cell physiology and signaling. Adv.Exp.Med.Biol. 2010;688:60–71. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6741-1_4. 60-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strub GM, Maceyka M, Hait NC, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Extracellular and intracellular actions of sphingosine-1-phosphate. Adv.Exp.Med.Biol. 2010;688:141–55. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6741-1_10. 141-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strub GM, Paillard M, Liang J, Gomez L, Allegood JC, Hait NC, Maceyka M, Price MM, Chen Q, Simpson DC, Kordula T, Milstien S, Lesnefsky EJ, Spiegel S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate produced by sphingosine kinase 2 in mitochondria interacts with prohibitin 2 to regulate complex IV assembly and respiration. The FASEB Journal. 2011;25(2):600–612. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-167502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland CM, Moretti PAB, Hewitt NM, Bagley CJ, Vadas MA, Pitson SM. The Calmodulin-binding Site of Sphingosine Kinase and Its Role in Agonist-dependent Translocation of Sphingosine Kinase 1 to the Plasma Membrane. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(17):11693–11701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601042200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taha TA, Kitatani K, El-Alwani M, Bielawski J, Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Loss of sphingosine kinase-1 activates the intrinsic pathway of programmed cell death: modulation of sphingolipid levels and the induction of apoptosis. The FASEB Journal. 2005;20(3):482–484. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4412fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ter Braak M, Danneberg K, Lichte K, Liphardt K, Ktistakis NT, Pitson SM, Hla T, Jakobs KH, Heringdorf D.M.z. G[alpha]q-mediated plasma membrane translocation of sphingosine kinase-1 and cross-activation of S1P receptors. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 2009;1791(5):357–370. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CR, Iyer SS, Melrose N, VanOosten R, Johnson K, Pitson SM, Obeid LM, Kusner DJ. Sphingosine Kinase 1 (SK1) Is Recruited to Nascent Phagosomes in Human Macrophages: Inhibition of SK1 Translocation by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The Journal of Immunology. 2005;174(6):3551–3561. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkataraman K, Thangada S, Michaud J, Oo ML, Ai Y, Lee YM, Wu M, Parikh NS, Khan F, Proia RL, Hla T. Extracellular export of sphingosine kinase-1a contributes to the vascular S1P gradient. Biochemical Journal. 2006;397(3):461–471. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wattenberg BW, Pitson SM, Raben DM. The sphingosine and diacylglycerol kinase superfamily of signaling kinases: localization as a key to signaling function. Journal of Lipid Research. 2006;47(6):1128–1139. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R600003-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigert A, Cremer S, Schmidt MV, von KA, Angioni C, Geisslinger G, Brune B. Cleavage of sphingosine kinase 2 by caspase-1 provokes its release from apoptotic cells. Blood. 2010;115(17):3531–3540. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-243444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia P, Wang L, Moretti PA, Albanese N, Chai F, Pitson SM, D′Andrea RJ, Gamble JR, Vadas MA. Sphingosine kinase interacts with TRAF2 and dissects tumor necrosis factor-alpha signaling. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(10):7996–8003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111423200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota S, Taniguchi Y, Kihara A, Mitsutake S, Igarashi Y. Asp177 in C4 domain of mouse sphingosine kinase 1a is important for the sphingosine recognition. FEBS Lett. 2004;578(1-2):106–110. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]