Introduction

There are approximately one million glomeruli in each human kidney. Each glomerulus is composed of a tuft of capillary loops supported by the mesangium and enclosed in a pouch-like extension of the renal tubule of the nephron known as Bowman’s capsule. The glomerulus consists of four resident cell types, the mesangial cell, the glomerular endothelial cell, the visceral epithelial cell (podocyte), and the parietal epithelial cell lining Bowman’s basement membrane. Recent experimental and clinical advances have identified the podocyte as the predominant cell of injury in glomerular diseases typified by heavy proteinuria, which is the focus of this article.

Structure, Function, and Injury of the Podocyte

Normal Structure of the Podocyte

-

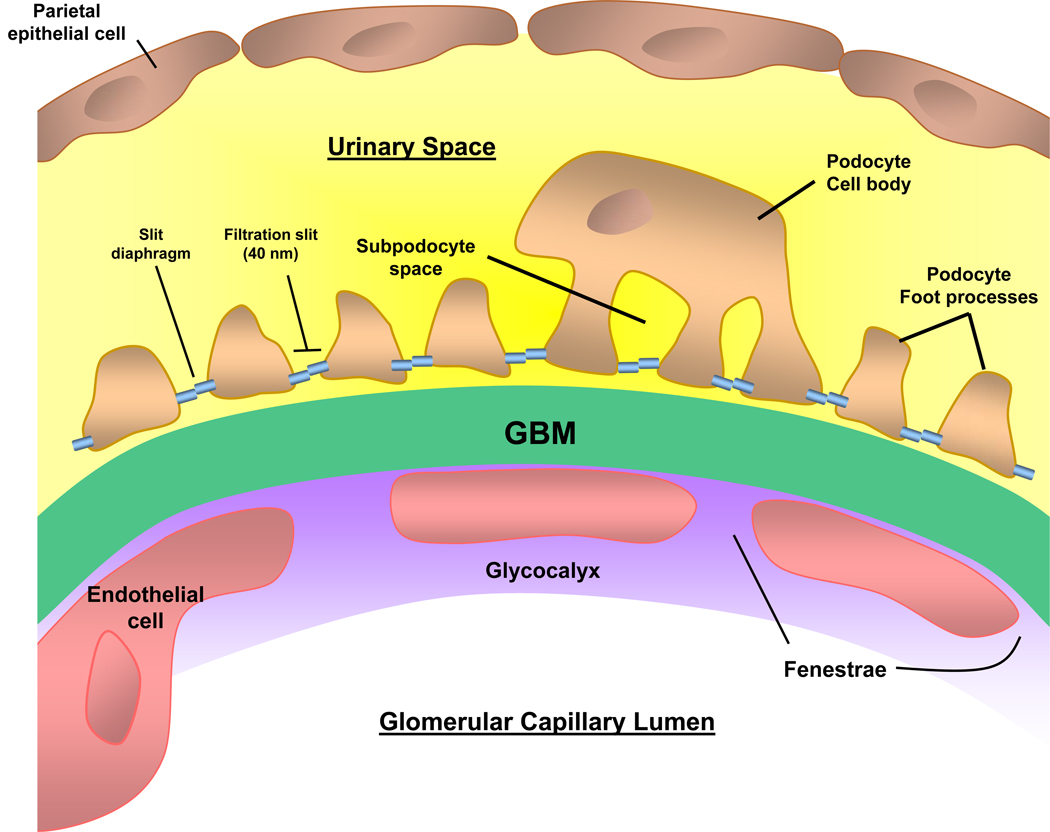

The podocyte is a highly differentiated epithelial cell sitting on the outside of the glomerular capillary loop

Consists of a large cell body (soma) in the urinary space

Connects to the underlying glomerular basement membrane (GBM) of the capillary loop by major cellular extensions from the soma

Extensions terminate as foot processes on the GBM that interdigitate with those from adjacent podocytes (Fig 1)

Podocyte foot processes are anchored to the GBM by α3β1 integrins and α- and β-dystroglycans

-

Between the foot processes, the filtration slit is bridged by a 40-nm wide zipper-like slit diaphragm

Slit diaphragm highly permeable to water and small solutes

Small pore size (5–15 nm) of slit diaphragm limits the passage of larger proteins, including albumin

Nephrin is the major component of the slit diaphragm, and is linked to the actin cytoskeleton by CD2AP (CD2-associated protein), podocin, and others

-

Roughly 500–600 podocytes per glomerular tuft in the adult human kidney

Rate of turnover is very slow

Very limited ability to proliferate

-

An extensive actin cytoskeleton

Allows dynamic contraction to support the glomerular capillary

Counteracts glomerular capillary hydrostatic pressure (~60 mm Hg), which is much greater than other capillary beds

Figure 1. Glomerular capillary wall.

The 3 layers of the capillary wall (glomerular endothelial cell, glomerular basement membrane (GBM), and podocyte) act as the glomerular filtration barrier (GFB) preventing proteins and large molecules from passing from the capillary lumen into the urinary space. The podocyte cell body lies with the urinary space, and the cell is attached to the GBM via the foot processes. Adjacent foot processes are separated by the filtration slit, bridged by the slit diaphragm. Disruption of the GFB leads the passage of protein across the capillary wall leading to proteinuria.

Major Functions of the Podocyte

Structural support of the capillary loop

Major component of glomerular filtration barrier (GFB) to proteins

Synthesis and repair of the GBM

-

Production of growth factors

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) traverses the GBM against the flow of glomerular filtration

Acts on VEGF receptors on the glomerular endothelial cells

Effect is to maintain a healthy fenestrated endothelium

Platelet derived growth factors (PDGFs) critical for development and migration of mesangial cells into the mesangium

-

-

Immunological function

Podocytes may be a component of the innate immune system

Possibly play a surveillance role for pathogens or abnormal proteins in Bowman’s space

Glomerular Filtration Barrier

Glomerular Filtration of Plasma Water

-

Occurs across the glomerular capillary walls into the urinary (Bowman’s) space

Approximately 180 L/day filtered

-

A portion of the glomerular ultrafiltrate is not filtered directly into the urinary space

Instead, goes first to a space underneath the podocyte cell body (subpodocyte space)

Subpodocyte space may play a role in restricting hydraulic permeability

-

GFB limits the passage of larger molecules such as albumin

Small amounts of protein (~4g/day) are normally filtered across the GFB into the urinary (Bowman’s) space

Vast majority of protein is reabsorbed in the proximal tubule via megalin/cubulin coreceptor

Structure of GFB

Composed of three layers (Fig 1); damage to one or more layers leads to proteinuria

-

Layer closest to lumen: fenestrated endothelial cells coated with glycocalyx

Fenestrations facilitate hydraulic permeability

Overlying glycocalyx (composed of a network of proteoglycans with negatively charged glycosaminoglycan side chains) limits the passage of albumin and larger molecules

-

Middle layer: GBM

-

Major component is type IV collagen

Early α1α2α1 collagen network secreted by the glomerular endothelial cell during fetal development is replaced by the more robust α3α4α5 collagen network secreted by the podocyte

Failure to secrete this network results in a range of hereditary nephropathies, the Type IV collagenopathies

Type IV collagenopathies include Alport syndrome, nail patella syndrome, thin basement membrane disease, and can all be considered podocyte disorders

-

Other GBM components include the glycoproteins laminin, entactin, and nidogen, and heparan-sulfate proteoglycans

Laminin serves as the predominant cell attachment ligand for podocyte and endothelial integrins

Heparan-sulfate proteoglycans confer an overall anionic charge

-

-

Layer closest to urinary space: podocytes

Multiple examples of both inherited and acquired podocyte injury, especially to proteins comprising the slit diaphragm domain, demonstrate the critical role of the podocyte in the prevention of proteinuria

Podocytes also maintain the GFB by removing protein and immunoglobulins that may clog the filter

Although injury to any layer may lead to proteinuria, nephrotic-range proteinuria is most typically due to diseases of podocytes

Podocyte Responses to Injury in Disease

Overview

Glomerular diseases comprise a wide range of immune and non-immune insults that may target, and thus injure, the podocyte

In many of these conditions, the podocytes respond to injury along defined pathways, which may explain the resultant clinical and histological changes

Reduction in Podocyte Number (Podocytopenia)

-

Potential causes (can occur in combination)

Detachment: podocytes may lose their ability to anchor to the GBM, detach into Bowman’s space, and shed into the urine

Apoptosis: podocytes may undergo programmed cell death

-

Inability to proliferate

Characteristic response of differentiated podocytes to most insults

Podocytes lost by detachment or apoptosis are not replaced by adjacent viable podocytes, leading to podocytopenia

Ultimate result is a leaky GFB

-

Consequences of podocytopenia

Glomerular capillaries denuded of podocytes balloon and form synechial attachments to Bowman’s capsule

Kriz hypothesis: these attachments can lead to the development of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS)

Recent evidence suggests that parietal epithelial cell precursors on Bowman’s basement membrane may serve as a source for podocyte replacement

Clinical studies in diabetic kidney disease have suggested that the degree of podocytopenia predicts progression of kidney disease

Podocyte Proliferation

May be rarely seen in de-differentiated podocytes

Feature of collapsing glomerulopathy

Foot Process effacement

-

Characteristic feature of proteinuric diseases

Readily seen on electron microscopy as flattening of foot processes

The only pathological abnormality seen in minimal change disease (MCD)

An active process induced by changes in the actin cytoskeleton

The flattened foot processes, which should not be considered as cells adherent to one another, severely disrupt in the normal shape and integrity of these cells

Other morphological changes characteristic of podocyte injury include microvillus transformation and the presence of protein reabsorption droplets

It is unclear if effacement alone may cause proteinuria, or if effacement is simply a manifestation of podocyte injury

Altered Slit Diaphragm Integrity

The slit diaphragm between adjacent podocyte foot processes is one of the major impediments to protein permeability across the glomerular capillary wall

Alterations in cytoskeletal architecture and/or expression of slit diaphragm proteins can be demonstrated in most nephrotic disorders

Production of Inflammatory Mediators

-

Podocytes may respond to immune complex-mediated injury by producing inflammatory mediators

Examples are oxidative radicals, proteases, eicosanoids, and chemokines, growth factors

Inflammatory mediators may amplify the initial podocyte injury

Oxidative injury is a prominent feature in membranous nephropathy

Suggested Reading

≫ Haraldsson B, Jeansson M. Glomerular filtration barrier. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2009;18(4):331–335.

≫ Jefferson JA, Shankland SJ, Pichler RH. Proteinuria in diabetic kidney disease: a mechanistic viewpoint. Kidney Int. 2008;74(1):22–36.

≫ Kriz W. The pathogenesis of 'classic' focal segmental glomerulosclerosis-lessons from rat models. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18(Suppl 6):vi39–44.

≫ Patrakka J, Tryggvason K. New insights into the role of podocytes in proteinuria. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5(8):463–468.

Nephrotic Syndrome

Classical Features of Nephrotic Syndrome

Heavy proteinuria (> 3.5 g/24 hr - also called nephrotic-range proteinuria)

Hypoalbuminemia (< 3 g/dl)

Peripheral edema

Hyperlipidemia (elevated total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol)

Lipiduria

Pathophysiology of Nephrotic Syndrome

-

Proteinuria and nephrotic syndrome are the clinical signatures of podocyte injury

Podocytes lie on the outside of the glomerular capillary, and are therefore separated from the circulation by the GBM

-

Subepithelial immune complexes (as in membranous nephropathy) or podocyte injury usually do not lead to leukocyte recruitment and inflammation, but rather disrupt the GFB

Typically urine sediment is devoid of leucocytes and erythrocytes

Disruption of GFB leads to proteinuria

By contrast, injury to mesangial or endothelial cells, which are in direct contact with the blood (containing leukocytes, complement, inflammatory proteins), typically leads to an inflammatory kidney disease (nephritis) with an active urine sediment

Clinical Manifestations and Complications of Nephrotic Syndrome

Hypoalbuminemia and Edema

Hypoalbuminemia may decrease the plasma oncotic pressure resulting in a decrease in effective circulating volume and activation of the renin angiotensin system leading to sodium retention (underfill theory)

-

In most cases however, edema appears to result from a primary defect in sodium excretion (ie, glomerular disease inhibits sodium excretion)

Leads to an expanded plasma volume

Followed by transudation of fluid in the setting of low oncotic pressure (overfill theory)

Hyperlipidemia

Hepatic cholesterol and lipoprotein synthesis are increased in nephrotic patients, probably in response to decreased oncotic pressure

There is also decreased catabolism, partly explaining the increase in levels of very low density lipoprotein

Lipiduria

Following glomerular filtration of lipoproteins, lipids may be taken up by proximal epithelial tubular cells

Desquamated proximal epithelial tubular cells containing lipid may be seen in the urine as oval fat bodies, or as lipid-containing granular casts (fatty casts)

Thrombosis

Hypercoagulability from increased hepatic synthesis of coagulation factors (eg, fibrinogen) and loss of regulatory factors (antithrombin III, protein C and protein S) in the urine

-

Kidney vein thrombosis complicates all forms of the nephrotic syndrome (especially membranous nephropathy)

May be asymptomatic

May present acutely as a sudden decrease in kidney function, loin pain, hematuria, or even systemic emboli

Infection

-

Increased susceptibility to infection

Particular vulnerability to Gram-positive bacteria

Caused by urinary losses of IgG and complement, plus impaired cellular immunity

Bone disease

Loss of vitamin D binding protein in the urine may lead to vitamin D deficiency

Also, treatment with steroids may exacerbate bone loss

Common Causes of Nephrotic Syndrome

-

Two categories of nephrotic syndrome etiology

Major pathology limited to, or predominantly, in the glomerulus

-

Systemic disorders, in which glomerular disease is a component of systemic manifestations (Box 1)

Systemic disorders do not manifest an idiopathic form limited to the glomerulus

Diabetic kidney disease is the most common systemic cause of nephrotic syndrome

Although mesangial cell injury is prominent in diabetic kidney disease, the proteinuria is likely a manifestation of podocyte injury

Each of the glomerular disorders may be idiopathic, or associated with other secondary causes (eg, membranous nephropathy secondary to lupus)

Box 1: Common Causes of Nephrotic Syndrome.

Predominant Glomerular Disease

Systemic Disorders with Glomerular Component

Diabetic kidney disease

Amyloidosis

Note: Podocyte injury is prominent in each of these conditions. Note that nephritic glomerular disorders [eg, IgA nephropathy] may also present with nephrotic-range proteinuria. Rare causes of nephrotic syndrome include fibrillary glomerulopathy, immunotactoid glomerulopathy, collagen III glomerulopathy, lipoprotein glomerulopathy, fibronectin glomerulopathy.

Abbreviations: FSGS, Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis; MPGN, Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis

General Therapeutic Strategies for Nephrotic Syndrome

-

Reduce proteinuria (to < 1 g/24 hr)

Use combination therapy with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and diuretics [+/− angiotensin receptor blocker, spironolactone]

Proteinuria reduction may slow the progression of kidney disease by ameliorating the tubular toxicity of filtered proteins

-

Treat any complications

Volume overload: salt restriction, diuretics

Hypertension: Blood pressure goal < 125/75 mm Hg.

Hyperlipidemia: statins

Thromboembolism: Aspirin; anticoagulation therapy for patients at high risk for venous thrombosis (eg, those with a serum albumin level < 2.0 g)

Bone disease: calcium and vitamin D supplementation

Treat any underlying secondary cause (eg, Hepatitis B in membranous nephropathy)

Provide disease-specific therapy (typically immunosuppression)

Suggested Reading

Clinical Podocyte Disorders

Minimal Change Disease

Epidemiology

Most common cause of nephrotic syndrome in children

Vast majority (90%) of cases occur in children less than 10 years of age

Therefore, most young children with nephrotic syndrome are treated empirically with steroids without kidney biopsy

Causes 10%-15% of adult nephrotic syndrome

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Podocyte injury typified by diffuse foot process effacement on electron microscopy

-

Evidence for a possible T-cell mediated cytokine leading to podocyte injury (Box 2)

-

Interleukin-13 (IL-13) is a recent candidate

Serum IL-13 levels are increased in patients with MCD

Rats overexpressing IL-13 develop minimal change type lesions

Angiopoietin-like 4 (ANGPTL4): overexpression in rat podocytes leads to a steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome

-

Proteinuria likely secondary to loss of slit diaphragm integrity and podocyte effacement; some evidence for decrease in glomerular charge barrier

Box 2: Secondary Causes of Minimal Change Disease.

Tumors (often T cell related)

Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Thymoma

Drugs and toxins

NSAIDs

Lithium

Bisphosphonate

Rarely: tiopronin, ampicillin, rifampicin, interferon

Other

Atopy/eczema

Chronic graft versus host disease

Abbreviations: NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

Pathology

Light microscopy: unremarkable

Immunofluorescence: unremarkable (rarely, C1q or IgM staining, which may herald a worse prognosis)

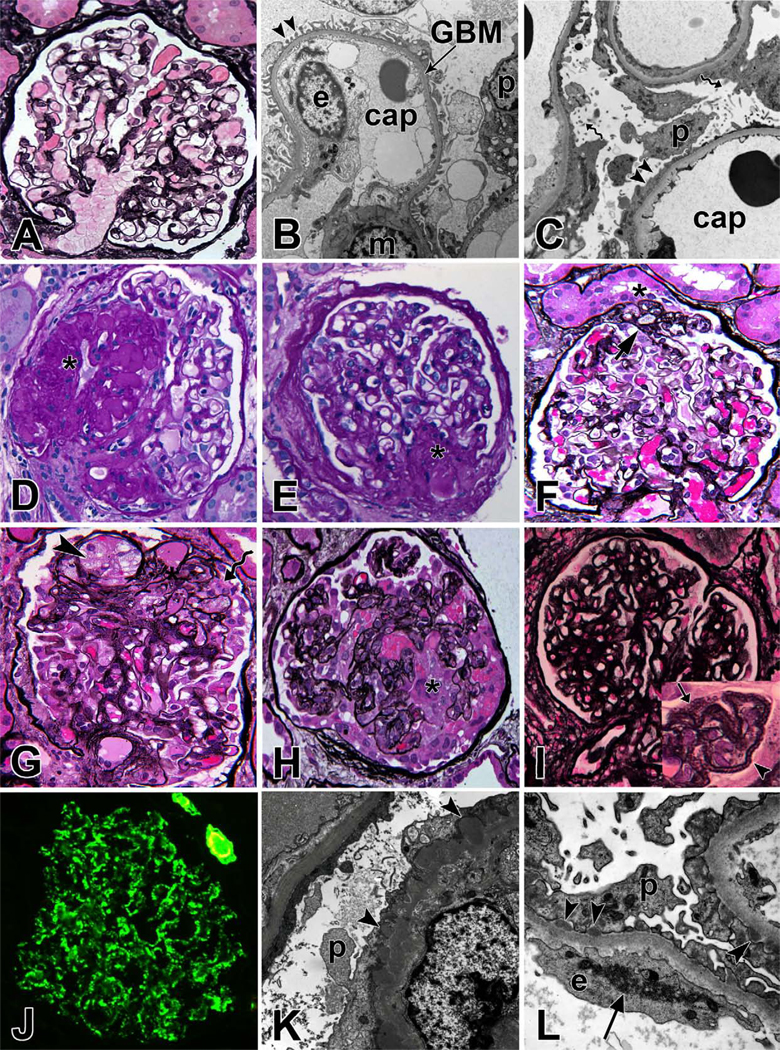

Electron microscopy shows characteristic diffuse effacement of podocyte foot processes (Fig 2C)

Figure 2. Renal Pathology of Clinical Podocyte Disorders.

(A) Light microscopy image of a normal glomerulus, Jones methenamine silver (JMS) stain; (B) Electron micrograph of a capillary loop from a normal glomerulus. Arrow heads point to regularly arranged intact foot processes. cap = capillary lumen, GBM = glomerular basement membrane, p = podocyte, e = endothelial cell; (C) Extensive effacement of foot processes (arrowheads) in minimal change disease. Spiral arrows point to microvillus transformation of podocytes; (D) Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), not otherwise specified (NOS) with obliterated capillary loops (*), hyalin deposition and adhesion of tuft to Bowman's capsule, periodic acid Schiff (PAS) stain; (E) FSGS, perihilar variant with segmental sclerosis at the vascular pole (*), PAS; (F) FSGS, tip variant with segmental sclerosis (arrow) located at the glomerulotubular junction (*), JMS; (G) FSGS, cellular variant with foam cells (arrowhead) infiltrating capillary loops of sclerotic segment and prominent overlying podocytes (spiral arrow), but no collapse of capillary loops, JMS; (H) FSGS, collapsing variant with collapse of capillary loops and podocyte proliferation (*), JMS; (I) Membranous nephropathy with thickened glomerular basement membrane. The inset shows a magnified view of capillary loops with frequent GBM holes (arrow) and spikes (arrowhead); (J) Immunofluorescent staining for IgG in membranous nephropathy shows global fine granular peripheral capillary wall staining pattern; (K) Electron micrograph of membranous nephropathy with subepithelial immune complex deposits (arrowhead) and extensive effacement of foot processes; (L) Electron micrograph of a case of membranous nephropathy secondary to lupus erythematosus. Arrow heads show subepithelial deposits and arrow shows an endothelial tubuloreticular inclusion, a common finding in lupus nephritis.

Clinical Features

Presents with acute-onset nephrotic syndrome (may be very heavy proteinuria (>10g/24h))

-

Associated features in adults

Include hematuria (~30%); hypertension (~40%); thrombosis (5%)

Acute kidney injury (AKI) occurs in 10%-25% (mostly older, severe nephrotic syndrome)

In children, hypertension less common, AKI may occur

Treatment

-

For adults, prednisone 1mg/kg daily (or 2mg/kg alternate days)

High dose until 2 weeks after complete remission (minimum 8 weeks)

Then taper over 2–4 months

-

Relapse rate is approximately 50%

Steroid dependent/multiply relapsing: each flare responds to steroid

Prolonged remission may be achieved with 3 month course cyclophosphamide (60%-70%) or with prolonged course of mycophenolate

-

Steroid resistant form occurs in 25%

failure to enter remission after 16 weeks high dose steroid

may respond to cyclosporin or mycophenolate

Steroid resistance suggests the possibility of not having identified FSGS on the biopsy specimen, due to sampling phenomenon

Children are typically more steroid sensitive, but high relapse rate (~70%) and 30%-40% will have multiple relapses

Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis

Overview

FSGS describes a histological pattern rather than a specific disease

Can be idiopathic or due to secondary causes from a variety of underlying disorders (Table 1)

“Focal” defines that less than 50% of glomeruli in the sample are affected

“Segmental” defines that only a portion of the effected glomerulus is sclerosed (scarred), while other portions of the glomerular tuft look normal by light microscopy

Table 1.

Etiological Classification of FSGS

| Classification/Etiology | Causes |

|---|---|

| Primary | |

| ? Circulating permeability factor |

|

| Secondary | |

| Glomerular hyperfiltration |

|

| Viral infection |

|

| Drugs & toxins |

|

| Familial | |

| Podocyte gene disorder |

|

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; CMV, cytomegalovirus; FSGS, Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis; INF2, inverted formin 2; CD2AP, CDs-associated protein; WT1, Wilms tumor 1; TRPC6, transient receptor potential cation channel 6;

Epidemiology

-

Increasing in prevalence

Has become the most common cause of nephrotic syndrome in adults

Higher prevalence in Black and Hispanic races

Most common cause of primary glomerular disease leading to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in the US

Although often considered a more advanced manifestation of MCD, many clinico-pathological features suggest FSGS is a completely separate group of diseases

FSGS often responds poorly to steroid therapy and commonly progresses to kidney failure

Pathology

Light microscopy

-

Lesion is defined by the early presence of an adhesion between a peripheral capillary loop and Bowman’s capsule

Progressive obliteration of the glomerular capillary lumen by acellular matrix-like material (Fig 2D)

Leads to a segmental scarring of the glomerular tuft

Uninvolved areas of the glomerular tuft are relatively normal

In addition to the clinical / etiological classification (Table 1), FSGS may be classified by histological features (Box 3)

Box 3: Columbia Pathological Classification of FSGS.

Not otherwise specified (NOS)

Classic FSGS

Perihilar variant

Exemplified in Figure 2E

More common in FSGS second to hyperfiltration as glomerular pressure highest closer to afferent arteriole (ie perihilar)

Tip variant

Exemplified in Figure 2F

Tuft adhesion at glomerular tip (the area adjacent to the origin of the proximal tubule, opposite the vascular pole)

Usually idiopathic, may be more steroid responsive

Cellular variant

Exemplified in Figure 2G

Segmental endocapillary hypercellularity

Intermediate prognosis between NOS and collapsing

Collapsing variant

Exemplified in Figure 2H

Tuft collapse with proliferation of overlying epithelial cells

Worst prognosis

Many consider this a separate disorder (collapsing glomerulopathy)

Abbreviations: NOS, not otherwise specified; FSGS, Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis

Immunofluorescence

C3, IgM, and fibrin staining in the sclerotic regions; otherwise unremarkable

Electron microscopy

Diffuse effacement of podocyte foot processes even in glomeruli seemingly uninvolved on light microscopy

Pathogenesis

Proteinuria due to an alteration in glomerular perm-selectivity in a similar manner to MCD (may be the glomeruli that appear normal on light microscopy that are mostly responsible for the proteinuria)

Ultrastructural examination of the podocyte shows evidence of cell injury with foot process effacement, cell hypertrophy, and the formation of pseudocysts

-

Podocyte detachment and apoptosis

Reduction in podocyte number

Loss of structural support to the capillary loop

Areas of denuded GBM, which can attach to the overlying parietal epithelial cells on Bowman’s basement membrane, forming synechiae

Capillary loops within the adhesion may deliver filtrate into interstitial areas rather than Bowman’s space, but ultimately collapse with thrombosis and hyalinosis

Primary FSGS

Immunological injury to the podocyte; exact mechanisms remain unclear

-

Circulating Permeability Factor

The rapid recurrence of primary FSGS after kidney transplant, sometimes as early as the first week, suggests a circulating host factor leads to podocyte injury

Cardiotrophin-like cytokine 1 (CLC1) is a recently proposed candidate

Secondary FSGS

Glomerular hyperfiltration: Loss of nephrons (reduced nephron mass) or dilation of the afferent arteriole (eg, obesity) may lead to glomerular hypertension and hyperfiltration

Chronic glomerular hypertension promotes podocyte injury and distension of the glomerular capillary

Glomerulomegaly (larger glomeruli may be more vulnerable to hyperfiltration injury and it is often the larger juxtamedullary glomeruli that develop glomerulosclerosis)

Black individuals have fewer, and larger glomeruli than Caucasians, which may partly explain the greater prevalence of FSGS

-

Nephron endowment

New nephrons continue to develop in the third trimester

Children born prematurely may have a decreased nephron number

Could predispose to glomerular hyperfiltration, with increased kidney disease and hypertension in later life

Clinical Features

Primary FSGS

Typically presents with severe nephrotic syndrome, which may be of acute onset

Associated with hematuria (~50%), hypertension (~60%) and reduced kidney function (25%-50%)

Prognosis heavily dependent on achievement of partial/complete remission with immunosuppression

Nonresponders have only 40% chance of a ten-year kidney survival

Secondary FSGS

Typically slower onset, less proteinuria

Serum albumin often preserved, less edema

Does not respond to immunosuppression, but overall prognosis much better

Treatment

-

Differentiate primary from secondary FSGS, as the latter are typically not steroid responsive

Clinical: assess for secondary causes, acuteness, and severity of nephrotic syndrome

Pathological: secondary FSGS suggested by glomerulomegaly, perihilar variant, and focal (<50%) effacement of foot processes

General therapy for nephrotic syndrome

-

Immunosuppression (for primary FSGS only) (Table 2)

Prednisone 1mg/kg (or 2mg/kg alternate days); prolonged course (up to 4 months) may be required before taper

Steroid resistant (50%): Consider cyclosporin 3–6mg/kg/day or mycophenolate mofetil 1g-1.5g bid

Table 2.

Immunosuppressive Treatment for Adult MCD and primary FSGS

| Initial Approach | Prednisone Duration |

Second-line Agents | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal Change Disease | |||

| Initial Therapy | Prednisone (1 mg/kg) (max of 80 mg/d) | Until 2 wk post complete remission (min of 8 wk) Taper over 2–4 mo | NA |

| Steroid Resistant | Prolonged high-dose steroid course | Discontinue after 4–6 mo if no response | MMF; cyclosporine; tacrolimus |

| Relapsing / steroid dependent | Try to detect early Repeat prednisone (1 mg/kg) Consider MMF or cyclosporin for induction | Shorter steroid course (4 wk high dose, taper 1–2 mo), then second-line agent | Oral cyclophosphamide (2 mg/kg for 12 wk); MMF; calcineurin inhibitors; rituximab |

| Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis | |||

| Initial Therapy | Prednisone (1 mg/kg) (max 80 mg/d) | Until 2 wk post complete remission (min 8 wk), then taper 2–4 mo | n/a |

| Partial Remission | Prolonged steroid course, as late complete remissions seen | High-dose steroid for 3–4 mo, then slow taper over 6–9 mo | Calcineurin inhibitors; MMF |

| Steroid Resistant | Prolonged steroid course | High dose for 4 mo Add second-line agent with taper | Calcineurin inhibitors; MMF |

| Relapsing / steroid dependent | Treat as MCD (above) | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MCD, Minimal Change Disease; max, maximum; min, minimum; NA, not applicable

Special Considerations

Collapsing Glomerulopathy

Classified as a pathological variant of FSGS, but many consider this a separate disease entity

Most commonly described secondary to HIV, but other secondary causes noted (Box 4)

Characteristic feature is the extracapillary proliferation of glomerular epithelial cells with collapse of glomerular tuft

Recent evidence suggests that podocyte injury results in de-differentiation and a renewed ability to proliferate and/or induction of aberrant hyperplastic repair by the parietal epithelial cells

-

HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN)

Almost exclusively in patients of African descent; associated with low CD4 counts and more advanced HIV infection

Typically presents with severe nephrotic syndrome, often progresses rapidly to ESRD (< 12months)

Surprisingly, patients are often normotensive

Evidence for direct infection of podocytes by HIV; tubular cell infection may account for the prominent tubular microcystic changes often found

Treatment with highly active antiretroviral therapy has dramatically changed the prevalence and prognosis for this condition

-

Non-HIV collapsing glomerulopathy

Predominately in patients of African descent, but more whites noted than in HIVAN

Clinical features and pathology similar to HIVAN; tubuloreticular structures are not typically found in non-HIV collapsing glomerulopathy

Box 4: Causes of Collapsing Glomerulopathy.

Infection

HIV

CMV

Parvovirus B19

Tuberculosis

Malignancy

Myeloma

Hemophagocytic syndrome

Acute leukemia

Drugs

Bisphosphonates

Interferons

Anabolic steroids

Autoimmune

Adult Still’s disease

Lupus

Mixed connective tissue disease

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; CMV, cytomegalovirus

Familial FSGS

Present at different ages with different modes of inheritance (Table 3)

Genetic testing is clinically available for most of these conditions

Establishing diagnosis may alter therapy as these disorders are typically resistant to immunosuppression

Familial FSGS is less likely to recur post-transplant

Sequence variants in the APOL1 (aloplipoprotein L-I) gene have been identified in African American patients with sporadic FSGS and hypertensive nephrosclerosis, which partly accounts for the increased prevalence in this group

Table 3.

Common Forms of Familial FSGS

| Gene (protein effected) |

Inheritance | Typical Age of Onset |

Distinguishing Clinical Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| NPHS1 (nephrin) | AR | infancy | Congenital nephrotic syndrome (Finnish type); severe nephrosis leading to ESRD |

| NPHS2 (podocin) | AR | 3 mo-5 y | 10–20% of SRNS in children |

| WT1 (Wilms tumor 1) | AD | child | Diffuse mesangial sclerosis/FSGS +/− Wilms tumor or urogenital lesions |

| PLCε1 (phospholipase Cε1) | AR | 4 mo-12 y | Diffuse mesangial sclerosis/FSGS |

| CD2AP (CD2- associated protein) | AR | <6 y | Rre, progresses to ESRD |

| INF2 (inverted formin 2) | AD | Teen/young adult | Mild nephrotic syndrome, but progressive CKD |

| ACTN4 (α- actinin 4) | AD | Any age | Mild nephrotic syndrome, may develop progressive CKD |

| TRPC6 | AD | Adult (age 20- 35) | Nephrotic, progressive CKD |

| tRNALeu(UUR) gene | Mitochondrial DNA | Adult | May be associated deafness, diabetes, muscle problems, retinopathy (maternal inheritance) |

Abbreviations: AR, autosomal recessive; AD, autosomal dominant; CKD, Chronic Kidney Disease; ESRD, End-Stage Renal Disease; FSGS, Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis; tRNA, transfer RNA; Leu, leucine; TRPC6, transient receptor potential cation channel 6;

Recurrent FSGS Posttransplant

-

Primary FSGS recurs in 20%-30% of patients

Typically within the first month, but can occur later

Early recurrence supports theory of circulating permeability factor

Graft loss 40%-50% without plasmapheresis

Treatment: plasmapheresis for 2–3 weeks, longer in some; cyclophosphamide may be appropriate

-

Risk Factors for recurrence

Young Age(< 15yrs)

Aggressive Course (< 3yrs from diagnosis to ESRD)

Race (less common in African Americans)

Living Donor (some recommend avoiding living donors in those at high risk for recurrence, but data not clear)

Membranous Nephropathy

Epidemiology

Membranous nephropathy (MN) is most common cause of nephrotic syndrome in Caucasians and older adults

Seen more often in males, rare in children

Mostly primary (idiopathic), although about 20% of cases are associated with clinical conditions such as cancer, infections, autoimmune disease and drugs (Box 5)

Familial membranous nephropathy has been described, but is rare

Box 5: Secondary Causes of Membranous Nephropathy.

Tumors

Carcinoma (lung, colon, rectum, stomach, breast, kidney), melanoma, leukemia/lymphoma

Infections

Hepatitis B, hepatitis C, syphilis, quartan Malaria, schistosomiasis, filariasis, hydatid disease, leprosy, scabies, tuberculosis

Drugs and Toxins

Gold, penicillamine, bucillamine, captopril, probenecid, NSAIDs, tiopronin, lithium, mercury, formaldehyde, hydrocarbons

Autoimmune Diseases

Systemic lupus erythematosis, rheumatoid arthritis, mixed connective tissue disease, Sjogren syndrome, Graves disease, Hashimoto thyroiditis, dermatomyositis, primary biliary cirrhosis, bullous pemphigoid, dermatitis herpetiformis, ankylosing spondylitis, Guillain-Barre syndrome, myasthenia gravis

Miscellaneous

Diabetes mellitus, sarcoidosis, sickle cell anemia, kimura disease, sclerosing cholangitis, systemic mastocytosis, Gardner-Diamond syndrome

Abbreviations: NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Characterized by the development of immune complexes in the subepithelial (subpodocyte) space

In primary MN, immune deposits likely develop in situ, due to the passage of preformed antibodies across the capillary wall targeting a specific podocyte antigen

-

The immune deposits consist of immunoglobulin (IgG, predominantly IgG4), complement components (C3, C5b-9), and antigen

Leads to podocyte damage, which causes increased production of extracellular matrix proteins along the GBM

Results in the characteristic thickening of the GBM, from which the name of the disease derives

-

Antigens in MN

-

M-type phospholipase A2 receptor (PLA2R)

Antibodies to PLA2R have been identified in 70% of patients with idiopathic MN

Antibody levels may correlate with disease activity and help identify patients suitable for immunosuppression

Anti-PLA2R antibodies not found in secondary forms of MN

Neutral endopeptidase: identified as the antigen in alloimmune neonatal MN occurring in newborns from neutral endopeptidase-deficient mothers

-

Subepithelial deposits of secondary MN

Believed to derive from circulating pre-formed immune complexes that dissociate and reform in the subepithelial space, or by the deposition of antigen alone (planted antigen), followed by antibody response

Range of antigens have been detected, including tumor antigens (carcinoembryonic antigen, prostate specific antigen), thyroglobulin, infection antigens (hepatitis B, hepatitis C, helicobacter pylori, syphilis) and DNA associated antigens (double-stranded DNA, histones, nucleosomes)

Unclear if antigens are causal or epiphenomena

-

Heymann nephritis model

A rat model of MN that has played a key role in identifying many of the pathogenic mechanisms in MN

Pathogenic antigen is megalin, but this is not expressed by human podocytes

-

-

Complement activation occurs, likely via the alternate pathway

C5b-9 is generated and inserts into podocyte membrane

Instead of cell lysis, a series of signaling events result in cell activation (release of reactive oxygen species, proteases and eicosanoids) and changes in podocyte structure

Pathology

Light Microscopy

At early stages, the glomeruli and interstitium look essentially normal

-

With disease progression, the pathognomonic thickening of capillary loops becomes evident

Accumulation of sub-epithelial immune complexes

Deposition of new basement membrane material by the podocyte

Staining with silver methenamine may reveal spikes representing new basement membrane material projecting between the immune deposits (Fig 2I)

Glomerular cellularity is typically normal

Immunofluorescence

Granular deposits of IgG in a subepithelial distribution (Fig 2J)

C1q, IgA, and IgM undetectable

Complement C3 present in about 50% of adult patients

Electron Microscopy

-

Characteristic subepithelial immune deposits

Initially small without a prominent basement membrane response

With time, basement membrane material projects around and encloses the immune deposits (Fig 2K)

Effacement of podocyte foot processes is found overlying the areas of electron dense deposits

Biopsy features suggestive of secondary MN include mesangial hypercellularity, leukocyte infiltration, the presence of C1q, IgA or IgM by immunofluoresence, or the presence of mesangial/subendothelial immune deposits or tubuloreticular structures by electron microscopy (Fig 2L)

Clinical Features of Idiopathic MN

Typically presents as nephrotic syndrome (80%), onset more gradual than MCD or primary FSGS

-

Associated features

Microhematuria is common (50%)

Blood pressure and kidney function typically normal at presentation.

Less severe disease in younger females and Asian race

Risk of kidney vein thrombosis higher than other forms of nephrotic syndrome

Natural History and Prognosis of Idiopathic MN

Course in adults is variable, but about 30%-40% develop progressive disease

30% undergo spontaneous remission (especially in younger females)

-

Prognostic risk factors for progression include:

Greater degree and duration of proteinuria

Impaired kidney function at presentation

Hypertension

Male sex and age older than 50 years

Non-Asian race

-

Biopsy features

glomerulosclerosis, FSGS, Stage III/IV disease, tubulointerstitial fibrosis

Has been argued that the pathological features on kidney biopsy do not give further prognostic risk stratification independent of the clinical variables

The urinary excretion of biomarkers such as β2-microglobulin and/or IgG may be more accurate prognostic indicators than total urinary protein excretion, although these assays are not widely available

Treatment of Idiopathic MN

-

Exclusion of Secondary Causes

Thorough history and examination

Check of antinuclear antibody, complement levels, Hepatitis B and C

-

Malignancy Screen

In general, the risk of malignancy is greatest in males and increases with age

Rare in those less than 40 years of age

Investigations may include stool guaics, colonoscopy, chest radiography, mammography and prostate specific antigen measurements

Screening recommendations are similar to the age appropriate cancer screening investigations for the general population

-

Assessment of Prognosis

Treatment is individualized based on the prognostic risk factors

Almost all patients are treated with the general measures outlined in the section on treatment of nephrotic syndrome

-

Immunosuppression is considered for patients at higher risk of progression (Table 4)

If the nephrotic syndrome is not too severe, 6 months’ close observation is often employed to determine if there is any evidence of a spontaneous remission (occurs in ~30% patients)

Cyclophosphamide or calcineurin inhibitor with steroid is usual first line therapy

Steroids alone are typically ineffective

Emerging data on rituximab is promising

Table 4.

Treatment of Membranous Nephropathy

| Risk Level | Approach | Immunosuppression |

|---|---|---|

| Low Risk (proteinuria <4 g/d, normal kidney function) | General measures* | None |

| Moderate risk (proteinuria 4- 8 g/d, normal kidney function) | General measures; observe for 6 mo | Cyclophosphamide + steroid (alternative is cyclosporin / tacrolimus) |

| High risk (proteinuria >8 g/d +/− reduced kidney function) | General measures; consider early immunosuppression | Cyclophosphamide + steroid (alternative is Cyclosporin / tacrolimus) |

see general measures for treatment of nephrotic syndrome.

Suggested Reading

≫ Waldman M, Crew RJ, Valeri A, et al. Adult minimal-change disease: clinical characteristics, treatment, and outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(3):445–453.

≫ Cattran DC, Alexopoulos E, Heering P, et al. Cyclosporin in idiopathic glomerular disease associated with the nephrotic syndrome: workshop recommendations. Kidney Int. 2007;72(12):1429–1447.

≫ D'Agati VD. The spectrum of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: new insights. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2008;17(3):271–281.

≫ Albaqumi M, Barisoni L. Current views on collapsing glomerulopathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(7):1276–1281.

≫ Machuca E, Benoit G, Antignac C. Genetics of nephrotic syndrome: connecting molecular genetics to podocyte physiology. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(R2):R185–194.

≫ Ulinski T. Recurrence of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis after kidney transplantation: strategies and outcome. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2010;15(5):628–632

≫ Beck LH, Jr., Bonegio RG, Lambeau G, et al. M-type phospholipase A2 receptor as target antigen in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(1):11–21.

≫ Glassock RJ. The pathogenesis of idiopathic membranous nephropathy: a 50-year odyssey. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56(1):157–167.

≫ Waldman M, Austin HA, 3rd. Controversies in the treatment of idiopathic membranous nephropathy. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5(8):469–479.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Statement: The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.