Abstract

Objective

To use microarray analyses of gene expression to characterize the synovial molecular pathways regulated by the arthritis regulatory locus Cia25, and how it operates to control disease severity and joint damage.

Methods

Synovial tissues from DA and DA.ACI(Cia25) rats obtained 21 days post-induction of pristane-induced arthritis were used for RNA extraction and hybridization to Illumina Rat-Ref 12 Beadchips (22,228 genes). A p-value ≤0.01 plus a fold-difference ≥1.5 were considered significant.

Results

IL-1β (7-fold), IL-6 (67-fold), Ccl2, Cxcl10, Mmp3, Mmp14, and innate immunity genes were expressed in increased levels in DA and in significantly lower levels in congenics. DA.ACI(Cia25) had increased expression of ten nuclear receptors (NR) genes, including those known to interfere with NFκB activity and cytokine expression, such as Lxrα, Pparγ, and Rxrγ. DA.ACI(Cia25) also had increased expression of NR targets suggesting increased NR activity. While the Vdr was not differentially expressed, a Vdr expression signature was detected in congenics, along with up-regulation of mediators of vitamin D synthesis.

Conclusions

This is the first description of the association between increased synovial levels of NRs and arthritis protection. The expression of NRs was inversely correlated with the expression of key mediators of arthritis suggesting reciprocally opposing effects either via NFκB or at the genomic level in the synovial tissue. We consider that the NR signature may have an important role in maintaining synovial homeostasis and an inflammation-free tissue. These processes are regulated by the Cia25 gene and suggest a new function for this gene.

INTRODUCTION

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic and erosive autoimmune polyarthritis that affects 0.5–1% of most populations (1). RA commonly causes joint deformities and is associated with increased risk for disability and reduced life expectancy (2). Genetic factors have a major role in disease susceptibility (3, 4), but little is known about the genes controlling disease severity and joint damage. Yet, disease severity correlates with disease outcome (5, 6) and mortality (2). While new biologic therapies have made a significant impact on quality of living and disease activity complete remission is still rarely achieved (7). Therefore, the identification of new genes and gene pathways implicated in the regulation of disease severity and joint damage has the potential to generate new tools for prognostication and new targets for therapy.

We have previously identified Cia25 on rat chromosome 12 as a new collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) (8) and pristane-induced arthritis (PIA) (9) severity and chronicity quantitative trait locus (QTL). Transfer of alleles derived from the arthritis-resistant strain ACI at Cia25, into the arthritis-susceptible and highly erosive DA strain, as in DA.ACI(Cia25) congenic rats, was enough to significantly reduce arthritis severity, confirming that this region harbors one at least one major disease gene.

Gene expression studies using microarrays have been successfully used to identify pathways and processes involved in the regulation of complex diseases such as cancers (10), as well as autoimmune diseases including systemic lupus (11), psoriatic arthritis (12) and RA (12, 13). In this study we used microarrays to study gene expression in synovial tissues from two nearly identical rat strains that differ only at the Cia25 congenic interval (DA.ACI(Cia25) and DA rats) in order to identify cellular and molecular pathways regulated by this locus (gene). Our studies determined that Cia25 regulates a) the expression of several pro-inflammatory and proteolytic genes that depend on, or are regulated by NFκB, as well as b) the expression of anti-inflammatory nuclear receptors (NRs) that among other functions also interfere with NFκB activation. NRs also have genomic activity, and a NR gene expression signature was detected in DA.ACI(Cia25) congenics and correlated with resistance to arthritis. Our observations suggest a new NR-associated homeostatic pathway aimed at preserving an inflammation-free synovial tissue.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Rats and breeding of DA.ACI(Cia25) congenic rats

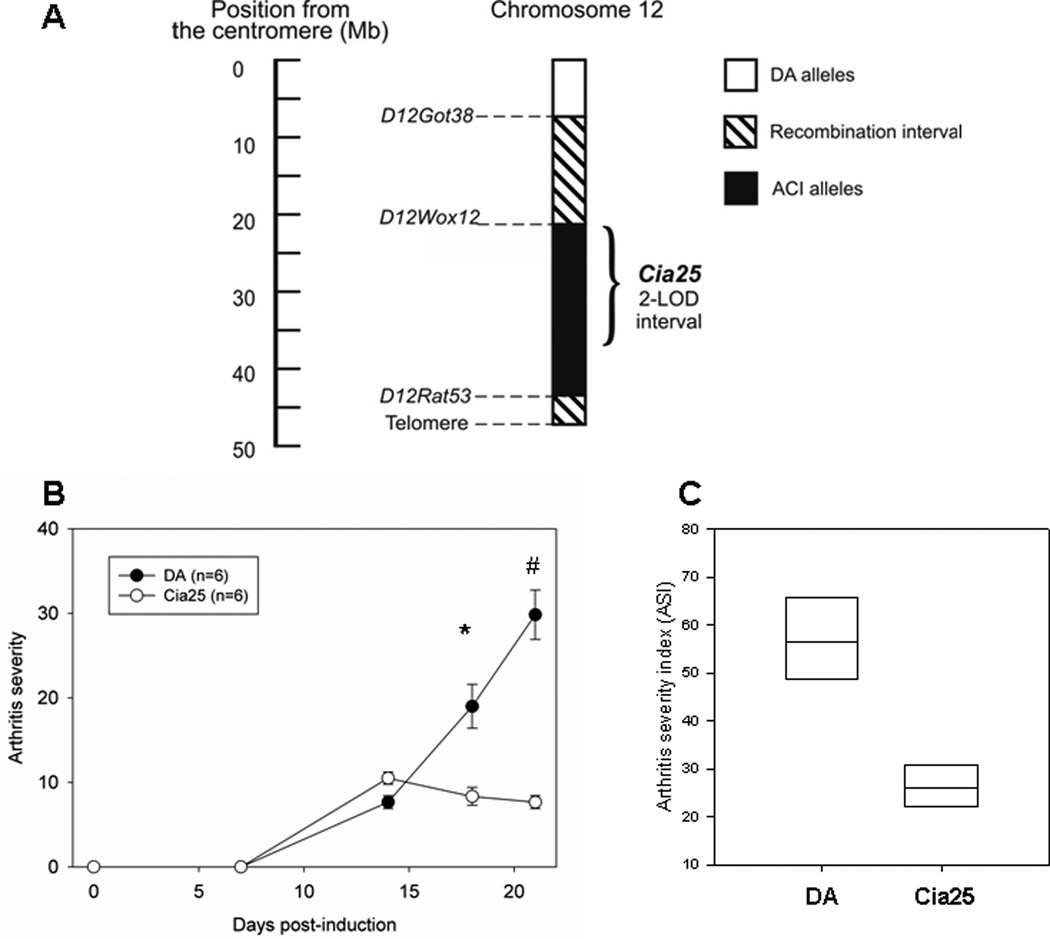

Specific pathogen free ACI (ACI/Hsd) and DA (DA/Hsd), inbred rat strains were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN) and used in the breeding of the DA.ACI(Cia25) congenic strain, as previously described (9). Briefly, a genotype-guided strategy was used to transfer a 23 Mb interval containing the 15.8 Mb two-logarithm of odds (LOD) support interval comprising the Cia25 fragment (8) from ACI into the DA background, and to generate homozygozity at the congenic interval (figure 1A). All experiments involving rats were approved by the Feinstein Institute Animal Care and Use Committee.

Figure 1. Map of the Cia25 congenic interval, and arthritis severity scores of DA and DA.ACI(Cia25) rats studied for 21 days after the induction of Pristane-Induced Arthritis.

A. Numbers on the y-axis represent positions relative to centromere in megabases (Mb). The position of the two-logarithm of odds (LOD) score support interval for Cia25 is shown with a brace. B. Scores were obtained on days 0, 7, 14, 18 and 21 following the induction. Data shown as means+S.E.M.. * P=0.004; # P=0.002; Mann-Whitney test. C. Cumulative 21-day arthritis severity index (ASI) shown as median with 25–75 percentiles, P=0.002; Mann-Whitney test.

Pristane-induced arthritis (PIA)

6 DA and 6 DA.ACI(Cia25) 8–12 week-old male rats were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine and injected intra-dermally with 150 µl of Pristane (2,6,10,14-tetramethylpentadecane, MP Bio, Solon, OH), divided into two injection sites at the base of the tail (day 0) (14, 15).

Arthritis severity scoring

Disease severity was determined with a well-established clinical scoring system (15). Animals were scored on days 0, 7, 14, 18 and 21 and the sum of all scores for each rat used as the cumulative arthritis severity index (ASI), which we have previously shown to correlate with histological damage, including synovial hyperplasia, and cartilage and bone erosive changes (15). ASI scores were compared with the Mann-Whitney non-parametric test using Sigmastat 3.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Synovial tissue collection and RNA extraction

Synovial tissues were collected from ankle joints of DA and DA.ACI(Cia25) congenics 21 days after the induction of PIA. After euthanasia the foot skin was cleaned and removed, and the Achilles tendon sectioned, followed by section of the posterior joint capsule and visualization of the ankle joint space. The synovial tissue is then easily identifiable. RNA was isolated from homogenized synovial tissues, using RNeasy (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), including a DNase step according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNAs were quantified and assessed for purity using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Rockland, DE), and integrity was verified with the BioAnalyzer 2100 (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA). Synovial tissues from six DA and six DA.ACI(Cia25) were used in the microarray experiments (one tissue sample per rat).

Isolation and culture of primary fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS)

FLS were isolated by enzymatic digestion of the synovial tissues as previously described (16). Briefly, tissues from a second group of DA and DA.ACI(Cia25) rats were minced and incubated with a solution containing DNase 0.15mg/ml, hyaluronidase type I-S 0.15 mg/ml, and collagenase type IA 1 mg/ml (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 1 hour at 37° C. Cells were washed and re-suspended in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (Invitrogen), glutamine 30 ng/ml, amphotericin B 250 µg/ml (Sigma), and gentamicin 10 ng/ml (Invitrogen). After overnight culture, non-adherent cells were removed and adherent cells were cultured. All experiments were performed with cells after passage four (>95% FLS purity).

Microarray experiments

The RatRef-12 Expression BeadChip contains 22,524 probes for a total of 22,228 rat genes selected primarily from the NCBI RefSeq database (Release 16) (Illumina, San Diego, CA), and was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All reagents have been optimized for use with Illumina’s Whole-Genome Expression platform. 200 ng of total RNA were used for cRNA in vitro transcription and labeling with the TotalPrep™ RNA Labeling Kit using Biotinylated-UTP (Ambion, Austin, TX). Hybridization was carried out in Illumina Intellihyb chambers at 58°C for 18.5 hours, followed by washing and staining according to the Illumina Hybridization System Manual. The signal was developed by staining with Cy3-streptavidin. The BeadChip was scanned on a high resolution Illumina BeadArray reader, using a two-channel, 0.8µm resolution confocal laser scanner.

Microarray data extraction, normalization and analyses

The Illumina BeadStudio software (Version 2.0) was used to extract and average-normalize the expression data (fluorescence intensities) for the mean intensity of all 12 arrays. Genes that were expressed in all 12 arrays were selected for analyses. Two additional strategies were used for the analyses of specific genes’ subsets: a) genes contained within the Cia25 interval and represented in the Illumina RatRef-12 Expression BeadChip were assessed for possible lack of expression in all DA or all congenics, as that could suggest the possibility of a major deletion or polymorphism that interfered with effective transcription; b) all genes represented in the Illumina BeadChip were assessed for possible expression only in one strain and not in the other.

The t-test was used to compare means of the log-transformed and non-log-transformed data. Genes with a p-value of ≤0.01 and a fold-difference ≥1.5 between DA and DA.ACI(Cia25) were considered significant and included in additional analysis.

The Ingenuity IPA 6.0 software (Ingenuity, Redwood City, CA), and Pubmed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) were used for pathway detection.

Real-time quantitative PCR (QPCR)

QPCR confirmation experiments were done as previously described (16), and used the same RNAs used in the microarray experiment plus additional samples from both DA and DA.ACI(Cia25). 200 ng of total RNA from each sample were used for cDNA synthesis using Superscript III (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Primers were designed to work with the Universal ProbeLibrary (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and Taqman (ABI, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) probes (supplemental table 1; http://www.nslij-genetics.org/gulko/). GAPDH was used as endogenous control. Samples were run in duplicates in an ABI 7700 QPCR thermocycler, and the means analyzed with the Sequence Detection System software version 1.9.1 (ABI). Results were obtained as Ct (threshold cycle) values. Relative expression of individual genes was adjusted for GAPDH in each sample (ΔCt), and ΔCt used for t-test analysis. QPCR fold-differences were calculated with the 2−ΔΔCt method.

RESULTS

DA.ACI(Cia25) congenics develop significantly milder arthritis (PIA)

Congenics developed minimal arthritis compared with DA (figure 1B and C), in agreement with our previous observations (9). The difference was detectable both on days 18 and 21 post-induction of PIA (figure 1B, p=0.004 and p=0.002, respectively; Mann-Whitney test) and translated into a greater than 50% reduction in median ASI in DA.ACI(Cia25) congenics, compared with DA (figure 1C, p=0.002).

Gene expression analysis of synovial tissues distinguishes DA.ACI(Cia25) from DA

7,707 genes were expressed in the synovial tissues of all DA and all DA.ACI(Cia25) congenic rats. Of these, 1,963 genes met the filtering criteria for significance (p≤0.01 and ≥1.5-fold difference). 1,019 genes had significantly increased expression in DA.ACI(Cia25), while 944 genes had significantly reduced expression in DA.ACI(Cia25), compared with DA. The differentially expressed genes included increased expression of genes implicated in immune and inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, cell cycle regulation, transcription factors, proteases, and matrix proteins in DA, and increased expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism and in xenobiotic metabolism in DA.ACI(Cia25) (supplemental tables 2 and 3).

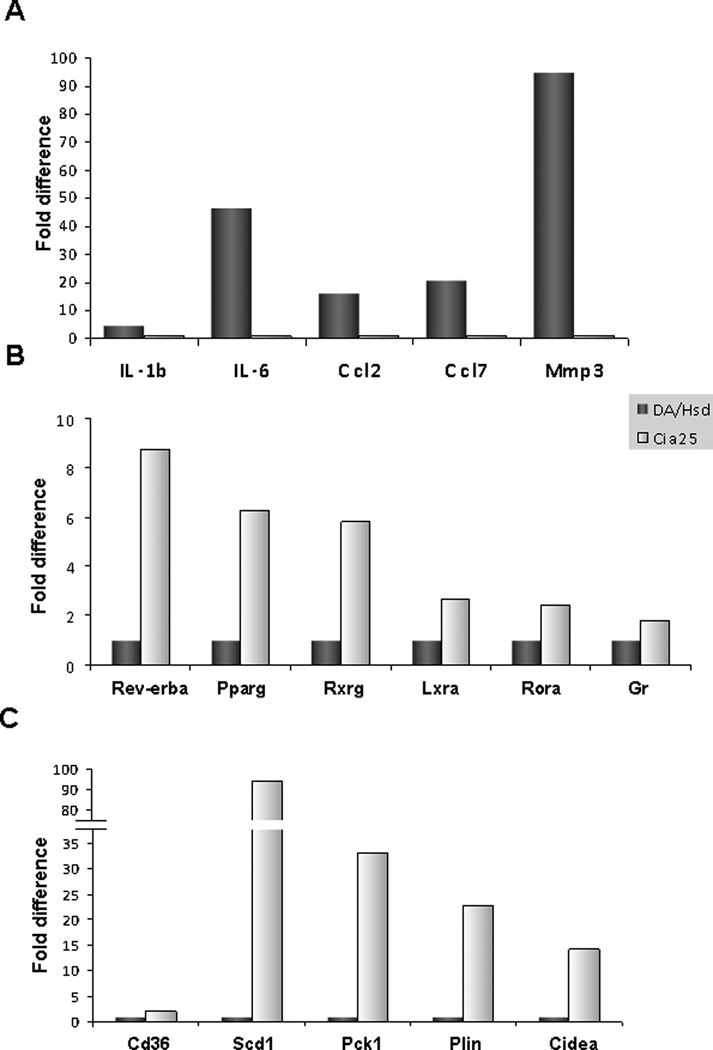

Reduced expression of IL-1β, IL-6, genes induced by these two cytokines, and reduced expression of other pro-inflammatory mediators in DA.ACI(Cia25) congenics

Genes implicated in innate immune responses, including IL-1β (7.4-fold), IL-6 (67-fold), lymphotoxin-β (Ltb), toll-like receptors (TLR) Tlr2 and Tlr7, and TLR and IL-1R signaling genes such as Irak4 and Tifa were expressed in increased levels in DA, and in reduced levels in DA.ACI(Cia25) congenics (table 1, figure 2A). Additionally, chemokines such as Ccl2, Ccl7, Ccl21, Cxcl10, and Cxcl13, and genes involved in acquired immune responses such as IL-13ra2, IL-17ra, were also expressed in increased levels in DA, and in reduced levels in congenics (table 1).

Table 1.

DA.ACI(Cia25) congenics have reduced expression levels of genes associated with inflammation and joint destruction, compared with DA.

| Gene | Gene Name | Accession number | DA mean | Cia25* mean | Fold difference¶ | P-value# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemokines and receptors | ||||||

| Ccl2 | c-chemokine ligand 2 | 24770 | 3340.50 | 480.11 | −6.96 | 0.006 |

| Ccl6 | c-chemokine ligand 6 | 287910 | 772.73 | 397.41 | −1.94 | 0.0002 |

| Ccl7 | c-chemokine ligand 7 | 287561 | 4349.99 | 281.89 | −15.43 | 0.005 |

| Ccr5 | c-chemokine receptor 5 | 117029 | 3784.07 | 524.28 | −7.22 | 0.002 |

| Cxcl10 | c-x-c chemokine ligand 10 | 245920 | 453.32 | 14.76 | −30.71 | 0.006 |

| Cxcl11 | c-x-c chemokine ligand 11 | 305236 | 1931.04 | 41.79 | −46.21 | 0.005 |

| Cxcl13 | c-x-c chemokine ligand 13 | 498335 | 4567.64 | 938.37 | −4.87 | 0.001 |

| Ccl21b | c-chemokine ligand 21b | 298006 | 2053.85 | 881.95 | −2.33 | 0.005 |

| Cytokines and receptors | ||||||

| IL-1β | interleukin-1 beta | 24494 | 1411.54 | 190.77 | −7.40 | 0.004 |

| IL-6 | interleukin-6 | 24498 | 827.06 | 12.28 | −67.33 | 0.06§ |

| IL-13ra2 | interleukin 13 receptor, alpha 2 | 171060 | 411.45 | 86.26 | −4.77 | 0.005 |

| IL-17ra | interleukin-17 receptor a | 312679 | 340.32 | 113.77 | −2.99 | 0.004 |

| Ltb | lymphotoxin beta | 361795 | 229.64 | 68.75 | −3.34 | 0.01 |

| TLR signaling | ||||||

| Tlr2 | toll-like receptor 2 | 310553 | 2169.30 | 656.32 | −3.31 | 0.0006 |

| Tlr6 | toll-like receptor 6 | 305353 | 652.13 | 367.79 | −1.77 | 0.0003 |

| Tlr7 | toll-like receptor 7 | 317468 | 188.78 | 57.09 | −3.31 | 0.0004 |

| TLR and IL-1r signaling | ||||||

| Irak4 | interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 4 | 300177 | 80.00 | 40.47 | −1.98 | 0.006 |

| TIFA | TRAF-interacting protein with forkhead-associated domain | 310877 | 905.22 | 321.12 | −2.82 | 0.00002 |

| Proteases | ||||||

| Mmp3 | matrix metallopeptidase 3 (stromelysin-1) | 171045 | 21189.32 | 1654.38 | −12.81 | 0.002 |

| Mmp14 | matrix metallopeptidase 14 (Mt1-mmp) | 81707 | 8999.14 | 2873.16 | −3.13 | 0.003 |

| Ctsc | Cathepsin C | 25423 | 1196.84 | 442.37 | −2.71 | 0.002 |

| Ctsd | Cathepsin D | 171293 | 5356.43 | 3095.15 | −1.73 | 0.0008 |

| Ctse | Cathepsin E | 25424 | 349.96 | 130.51 | −2.68 | 0.0001 |

Cia25=DA.ACI(Cia25);

Fold difference=Cia25 mean divided by DA mean;

Based on t-test;

QPCR IL-6 p-value=0.0002, with a 43.6-fold down-regulation in DA.ACI(Cia25).

Figure 2. QPCR confirmation of differentially expressed genes, including nuclear receptors and their signature genes.

A. QPCR confirmed the increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-6, chemokines Ccl2 and Ccl7 and Mmp3 in DA, compared with DA.ACI(Cia25) (P-values ≤ 0.0007; t-test.). B. The increased expression of six of the ten nuclear receptors expressed in increased levels in DA.ACI(Cia25) congenics (Cia25), compared with DA (DA/Hsd), was confirmed (four NRs were not tested with QPCR) (P-values ≤ 0.02, except for Gr: P=0.069). C. QPCR confirmation of the difference in expression of five nuclear receptor target genes, including Scd1 (P-values ≤ 0.002, except for Cd36 with 2.7-fold but P-value=0.15).

In addition to the difference in levels of IL-1β, we looked for evidence of increased IL-1β activity as measured by increased expression of IL-1β-inducible genes, and reduced expression of IL-1β-suppressed genes. 164 genes known to be transcriptionally regulated by IL-1β (17, 18) were represented in the Illumina rat microarray. Of these 164, sixteen IL-1β-inducible genes were expressed in increased levels in DA, compared with DA.ACI(Cia25), while seven IL-1β-suppressed genes were down in DA and up in congenics (supplemental table 4). The differential expression of 23 (14%) IL-1β -regulated genes was significantly more than expected by chance (p<0.001, Chi-square test). These results suggest that in addition to the increased expression of IL-1β in DA, there was also increased transcriptional activity associated with IL-1β. Four of the IL-1β-inducible genes were among the most significantly differentially expressed genes, namely IL-6, Ccl2, Ccl7 and Mmp3 and were confirmed by QPCR (supplemental table 4 and figure 2A). These observations further support a central role for IL-1β in our model.

IL-6 levels were significantly increased in DA, and we looked for evidence of differential IL-6 activity as measured by increased or decreased expression of IL-6-inducible genes. 46 genes known to be transcriptionally regulated by IL-6 (19) were present in the Illumina rat microarray. Of these 46, fifteen (37.5%) were expressed in increased levels in DA, compared with DA.ACI(Cia25) (supplemental table 4), which was significantly more than expected by chance (p<0.001, Chi-square test). These results suggest that in addition to its increased expression in DA and reduced expression in congenics, IL-6-mediated transcriptional activity was also different. Similar to the IL-1β scenario described above, IL-6-inducible genes were among the most significantly differentially expressed genes and included IL-6 itself, Cks2 (27.68-fold), Ccl2, Mmp3 and Mmp14 (supplemental table 4). Selected genes were confirmed with QPCR (supplemental table 4 and figure 2A).

Reduced expression of proteases in DA.ACI(Cia25) congenics

Genes encoding proteases implicated in joint damage and erosions such as Mmp3, Mmp14 (Mt1-Mmp), and cathepsins C, D and E, were expressed in reduced levels in DA.ACI(Cia25) congenics, compared with DA (table 1 and figure 2A). These observations suggest that in addition to regulating inflammatory responses, the Cia25 gene also regulates effector processes known to mediate joint and cartilage destruction.

Increased expression of nuclear receptor (NR) genes and up-regulation of NR targets, including Vdr targets, in synovial tissues from DA.ACI(Cia25)

Ten NR genes were expressed in significantly increased levels in the synovial tissues of DA.ACI(Cia25) congenics compared with DA (table 2). These included Pparγ (Nr1c3; 4.5-fold), Rev-erbα (Nr1d1; 4.1-fold), Rxrγ (Nr2b3; 3.1-fold), Rorα (Nr1f1; 1.9-fold), Lxrα (Nr1h3; 1.6-fold), the glucorticoid receptor (Gr; Nr3c1; 2.8-fold), the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR; Nr3c2; 1.8-fold), Arp1 (Nr2f2; 2.1-fold) and the thyroid hormone receptors α and β (Thrα, Nr1a1; 1.9-fold, and Thrβ, Nr1a2; 2.3-fold). These NRs have been implicated in the regulation of lipid metabolism and inflammatory processes among other functions. The differential expression of six NRs (Pparγ, Rev-erbα, Rxrγ, Rorα, Lxrα and Gr) was confirmed with QPCR (figure 2B).

Table 2.

Nuclear receptors expressed in increased levels in the synovial tissues of DA.ACI(Cia25) congenics, compared with DA.*

| Symbol | Gene Name | Official name# | DA mean | Cia25 mean | P-value | Fold diff. Cia25/DA§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pparg | peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma | Nr1c3 | 613.70 | 2819.07 | 0.00001 | 4.6 |

| Rev-erba | Rev-erb alpha | Nr1d1 | 292.05 | 1201.44 | 0.0002 | 4.1 |

| Rxrg | retinoid X receptor gamma | Nr2b3 | 384.23 | 1211.56 | 0.00002 | 3.2 |

| Gr | glucorticoid receptor | Nr3c1 | 71.20 | 203.65 | 0.00007 | 2.9 |

| Thrb | thyroid hormone receptor beta | Nr1a2 | 159.00 | 371.61 | 0.00007 | 2.3 |

| Arp1 | apolipoprotein regulatory protein 1 | Nr2f2 | 115.71 | 244.36 | 0.016** | 2.1 |

| Thra | thyroid hormone receptor alpha | Nr1a1 | 1073.44 | 2074.24 | 0.0002 | 1.9 |

| Rora | RAR-related orphan receptor alpha | Nr1f1 | 417.11 | 796.23 | 0.0002 | 1.9 |

| Mcr | mineralocorticoid receptor | Nr3c2 | 55.07 | 96.95 | 0.005 | 1.8 |

| Lxra | liver X receptor alpha | Nr1h3 | 1355.95 | 2175.24 | 0.002 | 1.6 |

Receptors in bold have been shown to mediate anti-inflammatory responses in in vivo models of autoimmunity and arthritis;

Nr=nuclear receptor

Fold difference of Cia25 versus DA expression.

suggestive p-value.

NRs are ligand-activated transcription factors. Therefore, we analyzed the expression levels of known NR target genes as a measure of the state of activation and function of the NRs. 34 Pparγ-regulated genes were significantly different between DA and DA.ACI(Cia25), which was more than expected by chance (p<0.001, Chi-square). 29 genes known to be up-regulated by Pparγ had increased expression in DA.ACI(Cia25) congenics, while four genes known to be down-regulated by Pparγ had reduced expression in congenics and increased expression in DA (table 3). Similar scenarios were detected with target genes of Rorα, Lxrα and the Vdr, even though the Vdr itself was not differentially expressed. Specifically, 7, 24 and 8 genes known to be up-regulated by Rorα, Lxrα and the Vdr, respectively, had increased expression in DA.ACI(Cia25) congenics, compared with DA (table 3). 11, 8 and 20 genes known to be down-regulated by Rorα, Lxrα and the Vdr, respectively, were expressed in reduced levels in congenics and had increased expression in DA (table 3). Some of the most significantly differentially expressed NR targets were confirmed with QPCR (figure 2C).

Table 3.

Expression of nuclear receptor target genes in DA and DA.ACI(Cia25) congenics§.

| Gene Symbol | Gene | Accession | Fold difference¶ | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pparg-induced genes (selected from a list of 29) | up in Cia25 | |||

| Pck1 | phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 | NM_198780.2 | 9.99 | 0.000004 |

| Plin | perilipin | NM_013094.1 | 6.45 | 0.000000 |

| Cidea | cell death-inducing DNA fragmentation factor | XM_214551.3 | 6.30 | 0.000004 |

| Scd1 | stearoyl-Coenzyme A desaturase 1 | NM_139192.1 | 5.25 | 0.0001 |

| Adipoq | adiponectin, C1Q and collagen domain containing | NM_144744.1 | 5.16 | 0.000006 |

| Pparg | nuclear receptor subfamily 1 (Nr1c3) | NM_013124.1 | 4.59 | 0.000005 |

| Rev-erba | nuclear receptor subfamily 1 (Nr1d1) | NM_145775.1 | 4.11 | 0.0003 |

| Cyp27a1 | cytochrome P450, family 27, subfamily a, polypeptide 1 | XM_579715.1 | 2.64 | 0.00003 |

| Cd36 | cd36 antigen | NM_031561.2 | 2.36 | 0.0001 |

| Lxra | liver X receptor alpha, (Nr1h3) | NM_031627 | 1.60 | 0.002 |

| Pparg-repressed genes | up in DA | |||

| Col5a2 | collagen, type V, alpha 2 | NM_053488.1 | 2.53 | 0.00002 |

| Col3a1 | collagen, type III, alpha 1 | NM_032085.1 | 2.47 | 0.00002 |

| Ralgds | ral guanine nucleotide dissociation stimulator | NM_001191753 | 1.56 | 0.003 |

| Pdgfra | platelet derived growth factor receptor | NM_012802.1 | 1.52 | 0.004 |

| Rora-induced genes | up in Cia25 | |||

| Slc2a4 | solute carrier family 2, member 4 (Glut4) | NM_012751.1 | 5.92 | 0.0000004 |

| Scd1 | stearoyl-Coenzyme A desaturase 1 | NM_139192.1 | 5.25 | 0.0001 |

| Srebf1 | sterol regulatory element binding factor 1 | XM_213329.3 | 4.34 | 0.000001 |

| Rev-erba | nuclear receptor subfamily 1 (Nr1d1) | NM_145775.1 | 4.11 | 0.0003 |

| Cnn1 | calponin 1, basic, smooth muscle | NM_031747.1 | 3.04 | 0.001 |

| Cd36 | cd36 antigen | NM_031561.2 | 2.36 | 0.0001 |

| Fabp4 | fatty acid binding protein 4 | XM_579554.1 | 2.09 | 0.0005 |

| Rora-repressed genes | up in DA | |||

| Mmp3 | matrix metallopeptidase 3 | NM_133523.2 | 12.81 | 0.002 |

| Timp1 | tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 | NM_053819.1 | 5.92 | 0.0002 |

| Cyp7b1 | cytochrome P450, 7b1 | NM_019138.1 | 3.59 | 0.003 |

| Ltb | lymphotoxin B | NM_212507.2 | 3.34 | 0.01 |

| Aif1 | allograft inflammatory factor 1 | NM_017196.3 | 3.07 | 0.000001 |

| Ucp2 | uncoupling protein 2 | NM_019354.2 | 2.68 | 0.00000004 |

| Stat2 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 | NM_001011905 | 2.46 | 0.0003 |

| Adrp | adipose differentiation-related protein | NM_001007144 | 2.25 | 0.00008 |

| Ctsk | cathepsin K | NM_031560.2 | 1.57 | 0.005 |

| Adam8 | a disintegrin and metalloprotease domain 8 | XM_574584.3 | 1.50 | 0.00007 |

| Lxra-induced genes (selected from a list of 24) | up in Cia25 | |||

| Thrsp | thyroid hormone responsive SPOT14 homolog | NM_012703.2 | 6.00 | 0.000005 |

| Slc2a4 | solute carrier family 2, member 4 (Glut4) | NM_012751.1 | 5.92 | 0.0000004 |

| Scd1 | stearoyl-Coenzyme A desaturase 1 | NM_139192.1 | 5.25 | 0.0001 |

| Pxmp2 | peroxisomal membrane protein | NM_031587.1 | 4.89 | 0.000003 |

| Pparg | nuclear receptor subfamily 1 (Nr1c3) | NM_013124.1 | 4.59 | 0.000005 |

| Srebf1 | sterol regulatory element binding factor 1 | XM_213329.3 | 4.34 | 0.000001 |

| Rev-erba | nuclear receptor subfamily 1 (Nr1d1) | NM_145775.1 | 4.11 | 0.0003 |

| Gstt1 | glutathione s transferase, theta 1 | NM_053293.2 | 3.53 | 0.000001 |

| Cd36 | cd36 antigen | NM_031561.2 | 2.36 | 0.0001 |

| Lxra | liver X receptor alpha, (Nr1h3) | NM_031627 | 1.60 | 0.002 |

| Lxra-repressed genes | up in DA | |||

| IL1b | interleukin-1 beta | NM_031512.2 | 7.40 | 0.004 |

| Ccl2 | c-chemokine ligand 2 | NM_031530.1 | 6.96 | 0.006 |

| Cyp7b1 | Cytochrome P450, 7b1 | NM_019138.1 | 3.59 | 0.003 |

| Pfkl | phosphofructokinase, liver, B-type | NM_013190.4 | 2.42 | 0.002 |

| Ppib | peptidylprolyl isomerase B (cyclophilin B) | NM_022536.1 | 1.75 | 0.00001 |

| Ahr | aryl hydrocarbon receptor | NM_013149.2 | 1.64 | 0.01 |

| Anxa2 | annexin A2 | NM_019905.1 | 1.58 | 0.0008 |

| Dnajc3 | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily C, member 3 | NM_022232.1 | 1.56 | 0.00005 |

| Vdr-induced genes | up in Cia25 | |||

| Rxrg | retinoid X receptor gamma (Nr2b3) | NM_031765.1 | 3.15 | 0.00002 |

| Thbd | thrombomodulin | NM_031771.2 | 2.67 | 0.00003 |

| Txnip | thioredoxin interacting protein | NM_001008767 | 2.35 | 0.000001 |

| Fabp4 | fatty acid binding protein 4 | XM_579554.1 | 2.09 | 0.0005 |

| Cdkn1b | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B | NM_031762.3 | 1.99 | 0.0001 |

| Gucy1b3 | guanylate cyclase 1, soluble, beta 3 | NM_012769.2 | 1.91 | 0.0008 |

| Tjp1 | tight junction protein 1 | NM_001106266 | 1.84 | 0.00002 |

| Polr2f | polymerase (RNA) II (DNA directed) polypeptide F | NM_031335.3 | 1.57 | 0.00008 |

| Vdr-repressed genes (selected from list of 20) | up in DA | |||

| Prc1 | protein regulator of cytokinesis 1 | NM_001107529 | 26.34 | 0.00005 |

| Pole2 | polymerase (DNA directed), epsilon 2 (p59 subunit) | NM_001169108 | 7.75 | 0.000001 |

| Cdca8 | cell division cycle associated 8 | NM_001025050 | 6.90 | 0.0003 |

| Rs21c6 | replication factor C (activator 1) 3 | NM_001009629 | 4.89 | 0.00002 |

| Myo5a | myosin Va | NM_022178.1 | 3.84 | 0.0006 |

| Smc2 | structural maintenance of chromosomes 2 | NM_001108666 | 3.23 | 0.0006 |

| Rfc3 | replication factor C (activator 1) 3 | NM_001009629 | 3.03 | 0.00007 |

| Kif22 | kinesin family, member 22 | NM_001009645 | 2.73 | 0.00009 |

| Rarres1 | retinoic acid receptor responder (tazarotene induced) | NM_001014790 | 2.45 | 0.004 |

| Tgfb1 | transforming growth factor beta 1 | NM_021578.2 | 1.95 | 0.001 |

Sections ordered according to fold-difference;

t-test;

gren font=up-regulated in Cia25 congenics and red font=up-regulated in DA synovium.

Oxysterols are synthesized from cholesterol, and activate Lxrα. DA synovial tissues had a significantly increased expression of the oxysterol-inactivating enzyme Cyp7b1 (3.6-fold), suggesting a reduction of potential ligands for activation of Lxrα, further contributing to or even causing a state of “Lxrα-deficiency” in this strain, as opposed to the DA.ACI(Cia25) congenics.

In addition to the increased Vdr expression signature we detected increased levels of cytochrome P450 (Cyp) genes such as Cyp27a1 (2.64-fold; P=0.00003), Cyp2j3 (3.47-fold; P=0.00009) and Cyp11a1 (9.31-fold; P=0.000002) in congenics. These Cyp enzymes regulate hydroxylation and synthesis of alternatively activated vitamin D products. These results suggest that increased in situ production of active forms of vitamin D may have contributed to the Vdr signature and reduced disease severity in the congenics.

Gr, Rxrγ and Rev-erbα were also expressed in increased levels in congenics compared with DA. However, we could not detect a clear Gr signature in either strain. Rxrγ dimerizes with Pparγ, Lxrα and the Vdr, and there is little information about specific targets, as opposed to targets shared with its heterodimer partners. Little information is also available about Rev-erbα specific targets, and therefore we could not establish whether its gene expression signature was present.

All NRs expressed in increased levels in the synovial tissues of DA.ACI(Cia25) are known to be expressed by macrophages. To determine whether FLS also expressed these NRs, cDNAs generated from DA and DA.ACI(Cia25) FLS were tested by PCR. FLS from both strains were positive for Pparγ, Rorα, Lxrα, Rev-erbα, Gr and Rxrγ.

The consistent observation of an increased expression of NR and NR-inducible genes in DA.ACI(Cia25), compared with DA, suggests increased NR activation in congenics, or a deficient state of activation in DA. This could be a novel genetically-regulated mechanism of preserving an inflammation-free synovial tissue depending on the alleles present at Cia25.

Differentially expressed genes contained within the Cia25 interval

28 of the genes differentially expressed are located within the 23 Mb Cia25 interval on rat chromosome 12 (supplemental table 5). 12 of these genes were expressed in increased levels in DA.ACI(Cia25) and 16 were increased in DA. Some of these genes reached a highly significant difference in expression, which may suggest a polymorphism at a regulatory region influencing transcription or mRNA stability. Two genes of note were Tesc with a 5-fold increased expression in congenics (p=0.000006) and Ncf1 with a 6.8-fold increased expression in DA (p=0.0009), both expressed by myeloid cells. Tesc is required for the differentiation of myeloid precursors into antigen-presenting and ROS producing cells, while Ncf1 is a member of the NADPH oxidase complex previously implicated in autoimmune arthritis.

Analysis of gene expression suggests reduced numbers of infiltrating macrophages in DA.ACI(Cia25) congenics

We considered that part of the differences in gene expression detected between DA and DA.ACI(Cia25) could be attributed to differences in synovial cellularity. We looked for macrophage, mast cell and T cell specific genes as proxies for the numbers of infiltrating cells. Three macrophage-specific genes were expressed in increased levels in DA versus DA.ACI(Cia25) (Cd163=6.9-fold, p=0.0005; Cd68=4.8-fold, p=0.00008; Crabp2=4.6-fold, p=0.001). These results, in combination with the increased expression of IL-1β, IL-6, Ncf1, Ncf2 and Ccr5 (supplemental table 2), suggested increased numbers of resident or infiltrating macrophages in DA synovial tissues. A single T cell-specific gene (CD3γ) was detected in the list of differentially expressed genes, and no T cell-derived cytokines were differentially expressed, suggesting no significant difference in the number of infiltrating T cells between DA and DA.ACI(Cia25) at this time-point (21 days from PIA induction). Three mast cell-specific genes were expressed in increased levels by DA.ACI(Cia25) congenics (Mcpt6, Tpsab1 and Cma1).

DISCUSSION

Little is known about the genetic regulation of RA severity and joint damage. We have previously identified the arthritis severity QTL Cia25, located on rat chromosome 12 (8, 9). In the present study we report that the presence of ACI alleles at the Cia25 interval in a DA background, as in DA.ACI(Cia25) congenics, was enough to significantly change the expression of several pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory genes. The congenics had reduced expression of several genes central to arthritis development and joint damage, both in rodent models as well as in RA, including IL-1β, IL-6, Ccl2 and Cxcl10, innate immune response genes, and proteases such as Mmp-3 and MT1-MMP. Additionally, DA.ACI(Cia25) had significantly increased expression of ten different NRs, most known to have anti-inflammatory properties including Lxrα, Pparγ, Rorα and Rxrγ. These NRs can interfere with NFκB activity, a known mediator of arthritis pathogenesis, synovial hyperplasia and joint damage (20, 21), while IL-1β and IL-6, among others, are known to be induced by and to induce NFκB activation. Several of the RA susceptibility genes are members or regulators of the NFκB pathway (4), making our observations even more relevant to human disease. Therefore, our results suggest that Cia25 is a novel regulator of the balance between NFκB activators and NFκB inhibitors, operating to maintain synovial homeostasis and preserving an inflammation-free synovial tissue.

This is the first time that eight of the ten NRs [Lxrα and Pparγ were previously detected but not functionally characterized in RA synovium (22, 23)] are identified in synovial tissues. Additionally, it was of great interest that the NRs were expressed in increased levels in arthritis-protected rats. NRs are ligand-activated transcription factors that regulate a variety of functions including lipid metabolism and aspects of the immune response. NRs have both genomic and non-genomic effects via their interaction with signaling pathways such as NFκB, STAT and AP-1, and can regulate the expression of IL-1β and IL-6. Interestingly, IL-1β reduces the expression of Pparγ (24) and Lxrα (25), supporting the concept of a mutual cytokine-NR antagonism.

Targets of NRs were also expressed in increased levels in the synovial tissues of congenic rats, suggesting that the up-regulated receptors also had increased transcriptional activity with a clear NR expression signature. The increased NR-induced signature could not be attributed to a single NR, as several NRs (Lxrα, Pparγ and Vdr) form heterodimers with Rxrγ, and thus share many common target genes.

Pparγ was the NR with the most significant increased expression in the synovial tissues of protected congenics. Pparγ was known to be expressed by RA synovium (22), however it was not known whether levels correlated with disease severity. Pparγ can be activated by endogenous lipids or synthetic agonists such as thiazolidinediones, and it suppresses macrophage activation by interfering with the activation of NFκB, AP-1 and STATs (26). Pparγ agonists ameliorate collagen and adjuvant-induced arthritis (CIA and AIA, respectively) and reduce joint erosions, and levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα (22).

Lxrα was expressed in increased levels in the synovial tissues of congenics, with a significant Lxrα-associated signature. Like Pparγ, Lxrα is involved in lipid metabolism and in the regulation of inflammation. Lxrα is activated by naturally occurring oxysterols to control cholesterol efflux and transport. While we were not able to quantify oxysterol levels in DA and congenics, we detected a significantly increased expression of the oxysterol-inactivating enzyme Cyp7b1 (27) (3.6-fold) in DA synovial tissues, suggesting that it could be reducing levels of ligands for Lxrα activation, creating a state of deficiency in this strain, as opposed to the DA.ACI(Cia25) congenics.

Activation of Lxrα with synthetic ligands reduces both the NFκB activity and the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators such as IL-1β, IL-6, Ccl2 and Ccl7 (28), and those were in fact reduced in congenics. Two recent reports demonstrated that Lxr agonists ameliorate CIA (23, 29), although a third study found opposite results (30). Lxrα agonists also ameliorate other models of inflammation and autoimmunity, including experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (31) and lupus (32).

Rorα is one of the retinoic acid orphan receptors with unclear endogenous agonists. Rorα was expressed in increased levels in DA.ACI(Cia25), and a Rorα expression signature was detected, suggesting a correlation between Rorα expression and activity with resistance to arthritis. This NR is implicated in lipid metabolism, and has anti-inflammatory properties via interference with NFκB activity and the expression of cytokines such as TNFα and IL-6 (33). Furthermore, Rorα-deficient mice have increased susceptibility to LPS-induced lung inflammation (34), and the use of a synthetic Rorα agonist ameliorated AIA in rats (35).

Rev-erbα was one of the NRs with the most significantly increased expression in DA.ACI(Cia25) congenics. It is activated by heme to repress transcription, interfering with cell circadian clock, and increasing adipocyte differentiation (36). Rev-erbα is expressed by macrophages, and as shown in this study, by FLS, but little is known about its possible anti-inflammatory properties, or target genes. However, the co-expression of Rev-erbα with anti-inflammatory NRs raises the interesting possibility that it might share that activity.

While the Vdr itself was not expressed in increased levels in DA.ACI(Cia25) congenics, a clear Vdr-associated expression signature was detected suggesting either increased levels of vitamin D in the blood, increased local synthesis with consequent increased Vdr activity, and/or intrinsic abnormalities in the Vdr activity and/or signaling. Indeed, in addition to the increased Vdr expression signature in synovial tissues of DA.ACI(Cia25), we also detected increased levels of Cyp27a1, Cyp2j3 and Cyp11a1, which regulate hydroxylation and synthesis of alternatively activated vitamin D products, respectively. Interestingly, Cyp27a1 can be induced by Pparγ and Lxrα (37), underscoring yet another possibility of inter-NR interactions that further enhance and amplify the anti-inflammatory effect in the synovial tissue.

Vdr activation increases levels of IκB and reduces NFκB activity, interfering with cellular responses to IL-1β and TNFα, including reduced production of IL-6 (38). Vitamin D treatment prevents (39) and also ameliorates established disease in CIA, reducing articular damage (40), again supporting our observations of an increased Vdr signature associated with disease resistance and articular protection.

The increased macrophage signature identified in DA, compared with DA.ACI(Cia25), suggests an inverse correlation between the presence of macrophages and the NR signature, further underscoring a potential role for Cia25 in preventing synovial inflammation.

IL-1β, IL-6 and their respective inducible genes were expressed in significantly higher levels in DA, and in lower levels in the protected DA.ACI(Cia25) congenics. These were important observations since IL-1β and IL-6 induce the expression of MMP-3 and other proteases, and are key mediators in arthritis pathogenesis and in articular damage (41, 42). IL-1β and IL-6 are expressed in increased levels in the synovial tissues of RA patients (43, 44) and rodents with arthritis (14, 45). Increased IL-1β activity (46) enhances arthritis severity, while the lack of IL-1β (47) or IL-6 (42) prevents disease development. Antagonism of IL-1β with IL-1ra (48), or blocking IL-1β or IL-6 with antibodies (41, 49, 50) ameliorates disease and reduces joint erosions, both in rodent models and in patients with RA. Therefore, our observations suggest a central transcriptome effect of IL-1β and IL-6 in arthritis, and point to Cia25 as a new regulator of IL-1β and IL-6 expression and activity.

In conclusion, we consider that the Cia25 gene is directly or indirectly involved in the regulation of NR expression and activity, and perhaps the synthesis of certain ligands such as vitamin D and oxysterols, in synovial tissues. We further consider that the state of activation of NRs could operate as an ‘on-off switch’ to regulate NFκB activity, and to reduce the expression and cell responsiveness to IL-1β and IL-6, thus protecting the synovial tissue from becoming a chemokine-producing, inflammation-fostering and protease-rich tissue that causes articular damage. Future work should determine how NRs operate to regulate arthritis severity and joint damage, which signaling pathways are involved, and whether NRs affect the invasive properties of FLS, as well as the function of other synovial-infiltrating or resident cells. Our observations raise the possibility that NRs might be interesting targets for the development of new therapies for RA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funded by a Postdoctoral Fellowship Award from the Arthritis Foundation (New Jersey Chapter) to Dr. M. Brenner, and by the National Institutes of Health grants R01-AR46213, R01-AR052439 (NIAMS) and R01-AI54348 (NIAID) to Dr. P. Gulko.

Footnotes

(supplemental tables will be available at http://www.nslij-genetics.org/gulko/ and data will be submitted to GEO upon the acceptance of the manuscript).

REFERENCES

- 1.Seldin MF, Amos CI, Ward R, Gregersen PK. The genetics revolution and the assault on rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(6):1071–1079. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199906)42:6<1071::AID-ANR1>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe F, Mitchell DM, Sibley JT, Fries JF, Bloch DA, Williams CA, et al. The mortality of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37(4):481–494. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plenge RM, Seielstad M, Padyukov L, Lee AT, Remmers EF, Ding B, et al. TRAF1-C5 as a risk locus for rheumatoid arthritis--a genomewide study. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(12):1199–1209. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gregersen PK, Amos CI, Lee AT, Lu Y, Remmers EF, Kastner DL, et al. REL, encoding a member of the NF-kappaB family of transcription factors, is a newly defined risk locus for rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Genet. 2009;41(7):820–823. doi: 10.1038/ng.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Zeben D, Breedveld FC. Prognostic factors in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1996;44:31–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gossec L, Dougados M, Goupille P, Cantagrel A, Sibilia J, Meyer O, et al. Prognostic factors for remission in early rheumatoid arthritis: a multiparameter prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(6):675–680. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.010611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolfe F, Rasker JJ, Boers M, Wells GA, Michaud K. Minimal disease activity, remission, and the long-term outcomes of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(6):935–942. doi: 10.1002/art.22895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meng H, Griffiths M, Remmers E, Kawahito Y, Li W, Neisa R, et al. Identification of two novel female-specific non-MHC loci regulating collagen-induced arthritis severity and chronicity, and evidence of epistasis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(8):2695–2705. doi: 10.1002/art.20366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brenner M, Laragione T, Mello A, Gulko PS. Cia25 on rat chromosome 12 regulates severity of autoimmune arthritis induced with pristane and with collagen. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(7):952–957. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.066225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu Y, Khan J, Khanna C, Helman L, Meltzer PS, Merlino G. Expression profiling identifies the cytoskeletal organizer ezrin and the developmental homeoprotein Six-1 as key metastatic regulators. Nat Med. 2004;10(2):175–181. doi: 10.1038/nm966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baechler EC, Batliwalla FM, Karypis G, Gaffney PM, Ortmann WA, Espe KJ, et al. Interferon-inducible gene expression signature in peripheral blood cells of patients with severe lupus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(5):2610–2615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337679100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Batliwalla FM, Li W, Ritchlin CT, Xiao X, Brenner M, Laragione T, et al. Microarray analyses of peripheral blood cells identifies unique gene expression signature in psoriatic arthritis. Mol Med. 2005;11(1–12):21–29. doi: 10.2119/2006-00003.Gulko. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasperkovitz PV, Timmer TC, Smeets TJ, Verbeet NL, Tak PP, van Baarsen LG, et al. Fibroblast-like synoviocytes derived from patients with rheumatoid arthritis show the imprint of synovial tissue heterogeneity: evidence of a link between an increased myofibroblast-like phenotype and high-inflammation synovitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(2):430–441. doi: 10.1002/art.20811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vingsbo C, Sahlstrand P, Brun J, Jonsson R, Saxne T, Holmdahl R. Pristane-induced arthritis in rats: A new model for rheumatoid arthritis with a chronic disease course influenced by both major histocompatibility complex and non-major histocompatibility complex genes. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:1675–1683. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brenner M, Meng H, Yarlett N, Griffiths M, Remmers E, Wilder R, et al. The non-MHC quantitative trait locus Cia10 contains a major arthritis gene and regulates disease severity, pannus formation and joint damage. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(1):322–332. doi: 10.1002/art.20782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laragione T, Brenner M, Mello A, Symons M, Gulko PS. The arthritis severity locus Cia5d is a novel genetic regulator of the invasive properties of synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(8):2296–2306. doi: 10.1002/art.23610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taberner M, Scott KF, Weininger L, Mackay CR, Rolph MS. Overlapping gene expression profiles in rheumatoid fibroblast-like synoviocytes induced by the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-1 beta and tumor necrosis factor. Inflamm Res. 2005;54(1):10–16. doi: 10.1007/s00011-004-1315-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vincenti MP, Brinckerhoff CE. Early response genes induced in chondrocytes stimulated with the inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1beta. Arthritis Res. 2001;3(6):381–388. doi: 10.1186/ar331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dasu MR, Hawkins HK, Barrow RE, Xue H, Herndon DN. Gene expression profiles from hypertrophic scar fibroblasts before and after IL-6 stimulation. J Pathol. 2004;202(4):476–485. doi: 10.1002/path.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schopf L, Savinainen A, Anderson K, Kujawa J, DuPont M, Silva M, et al. IKKbeta inhibition protects against bone and cartilage destruction in a rat model of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(10):3163–3173. doi: 10.1002/art.22081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miagkov AV, Kovalenko DV, Brown CE, Didsbury JR, Cogswell JP, Stimpson SA, et al. NF-kappaB activation provides the potential link between inflammation and hyperplasia in the arthritic joint. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(23):13859–13864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawahito Y, Kondo M, Tsubouchi Y, Hashiramoto A, Bishop-Bailey D, Inoue K, et al. 15-deoxy-delta(12,14)-PGJ(2) induces synoviocyte apoptosis and suppresses adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(2):189–197. doi: 10.1172/JCI9652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chintalacharuvu SR, Sandusky GE, Burris TP, Burmer GC, Nagpal S. Liver X receptor is a therapeutic target in collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(4):1365–1367. doi: 10.1002/art.22528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Afif H, Benderdour M, Mfuna-Endam L, Martel-Pelletier J, Pelletier JP, Duval N, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma1 expression is diminished in human osteoarthritic cartilage and is downregulated by interleukin-1beta in articular chondrocytes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(2):R31. doi: 10.1186/ar2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim MS, Sweeney TR, Shigenaga JK, Chui LG, Moser A, Grunfeld C, et al. Tumor necrosis factor and interleukin 1 decrease RXRalpha, PPARalpha, PPARgamma, LXRalpha, and the coactivators SRC-1, PGC-1alpha, and PGC-1beta in liver cells. Metabolism. 2007;56(2):267–279. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ricote M, Li AC, Willson TM, Kelly CJ, Glass CK. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma is a negative regulator of macrophage activation. Nature. 1998;391(6662):79–82. doi: 10.1038/34178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li-Hawkins J, Lund EG, Turley SD, Russell DW. Disruption of the oxysterol 7alpha-hydroxylase gene in mice. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(22):16536–16542. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joseph SB, Castrillo A, Laffitte BA, Mangelsdorf DJ, Tontonoz P. Reciprocal regulation of inflammation and lipid metabolism by liver X receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9(2):213–219. doi: 10.1038/nm820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park MC, Kwon YJ, Chung SJ, Park YB, Lee SK. Liver X receptor agonist prevents the evolution of collagen-induced arthritis in mice. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49(5):882–890. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asquith DL, Miller AM, Hueber AJ, McKinnon HJ, Sattar N, Graham GJ, et al. Liver X receptor agonism promotes articular inflammation in murine collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(9):2655–2665. doi: 10.1002/art.24717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hindinger C, Hinton DR, Kirwin SJ, Atkinson RD, Burnett ME, Bergmann CC, et al. Liver X receptor activation decreases the severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neurosci Res. 2006;84(6):1225–1234. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.A-Gonzalez N, Bensinger SJ, Hong C, Beceiro S, Bradley MN, Zelcer N, et al. Apoptotic cells promote their own clearance and immune tolerance through activation of the nuclear receptor LXR. Immunity. 2009;31(2):245–258. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delerive P, Monte D, Dubois G, Trottein F, Fruchart-Najib J, Mariani J, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor ROR alpha is a negative regulator of the inflammatory response. EMBO Rep. 2001;2(1):42–48. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stapleton CM, Jaradat M, Dixon D, Kang HS, Kim SC, Liao G, et al. Enhanced susceptibility of staggerer (RORalphasg/sg) mice to lipopolysaccharide-induced lung inflammation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289(1):L144–L152. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00348.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiesenberg I, Chiesi M, Missbach M, Spanka C, Pignat W, Carlberg C. Specific activation of the nuclear receptors PPARgamma and RORA by the antidiabetic thiazolidinedione BRL 49653 and the antiarthritic thiazolidinedione derivative CGP 52608. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;53(6):1131–1138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yin L, Wu N, Curtin JC, Qatanani M, Szwergold NR, Reid RA, et al. Rev-erbalpha, a heme sensor that coordinates metabolic and circadian pathways. Science. 2007;318(5857):1786–1789. doi: 10.1126/science.1150179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szanto A, Benko S, Szatmari I, Balint BL, Furtos I, Ruhl R, et al. Transcriptional regulation of human CYP27 integrates retinoid, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor, and liver X receptor signaling in macrophages. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(18):8154–8166. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.18.8154-8166.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szeto FL, Sun J, Kong J, Duan Y, Liao A, Madara JL, et al. Involvement of the vitamin D receptor in the regulation of NF-kappaB activity in fibroblasts. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103(3–5):563–566. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.12.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsuji M, Fujii K, Nakano T, Nishii Y. 1 alpha-hydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits type II collagen-induced arthritis in rats. FEBS Lett. 1994;337(3):248–250. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80201-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cantorna MT, Hayes CE, DeLuca HF. 1,25-Dihydroxycholecalciferol inhibits the progression of arthritis in murine models of human arthritis. J Nutr. 1998;128(1):68–72. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joosten LA, Helsen MM, Saxne T, van De Loo FA, Heinegard D, van Den Berg WB. IL-1 alpha beta blockade prevents cartilage and bone destruction in murine type II collagen-induced arthritis, whereas TNF-alpha blockade only ameliorates joint inflammation. J Immunol. 1999;163(9):5049–5055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alonzi T, Fattori E, Lazzaro D, Costa P, Probert L, Kollias G, et al. Interleukin 6 is required for the development of collagen-induced arthritis. J Exp Med. 1998;187(4):461–468. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.4.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Firestein GS, Boyle DL, Yu C, Paine MM, Whisenand TD, Zvaifler NJ, et al. Synovial interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and interleukin-1 balance in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37(5):644–652. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guerne PA, Zuraw BL, Vaughan JH, Carson DA, Lotz M. Synovium as a source of interleukin 6 in vitro. Contribution to local and systemic manifestations of arthritis. J Clin Invest. 1989;83(2):585–592. doi: 10.1172/JCI113921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marinova-Mutafchieva L, Williams RO, Mason LJ, Mauri C, Feldmann M, Maini RN. Dynamics of proinflammatory cytokine expression in the joints of mice with collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;107(3):507–512. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.2901181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horai R, Saijo S, Tanioka H, Nakae S, Sudo K, Okahara A, et al. Development of chronic inflammatory arthropathy resembling rheumatoid arthritis in interleukin 1 receptor antagonist-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2000;191(2):313–320. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.2.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saijo S, Asano M, Horai R, Yamamoto H, Iwakura Y. Suppression of autoimmune arthritis in interleukin-1-deficient mice in which T cell activation is impaired due to low levels of CD40 ligand and OX40 expression on T cells. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(2):533–544. doi: 10.1002/art.10172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jiang Y, Genant HK, Watt I, Cobby M, Bresnihan B, Aitchison R, et al. A multicenter, double-blind, dose-ranging, randomized, placebo-controlled study of recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: radiologic progression and correlation of Genant and Larsen scores. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(5):1001–1009. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200005)43:5<1001::AID-ANR7>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takagi N, Mihara M, Moriya Y, Nishimoto N, Yoshizaki K, Kishimoto T, et al. Blockage of interleukin-6 receptor ameliorates joint disease in murine collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(12):2117–2121. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199812)41:12<2117::AID-ART6>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nishimoto N, Hashimoto J, Miyasaka N, Yamamoto K, Kawai S, Takeuchi T, et al. Study of active controlled monotherapy used for rheumatoid arthritis, an IL-6 inhibitor (SAMURAI): evidence of clinical and radiographic benefit from an x ray reader-blinded randomised controlled trial of tocilizumab. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(9):1162–1167. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.068064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.