Abstract

Postpartum female rodents are less anxious than diestrous virgins and this difference contributes to dams’ ability to adequately care for pups and defend the nest. Low postpartum anxiety has been observed in many behavioral paradigms but the results of previous studies using the light-dark box have been inconsistent. We here reexamined the usefulness of the light-dark box to assess differences between postpartum and diestrous virgin female rats in anxiety-related behavior. We found a significant effect of reproductive state, such that dams spent more time in the light chamber than did diestrous virgins. This difference required recent physical contact with pups because a four-hour separation from pups reduced dams’ time spent in the light chamber by half, similar to what we previously found for litter-separated dams tested in an elevated plus maze. Lastly, we examined if dams’ low-anxiety behavior in the light-dark box depends on high GABAA receptor activity by inhibiting the receptor at different binding sites using (+)-Bicuculline to target the GABA site, FG-7142 to target the benzodiazepine site, and pentylenetetrazol to target the picrotoxin site. Only pentylenetetrazol was consistently anxiogenic in dams, while having little effect in diestrous virgins. Thus, the light-dark box can be a useful paradigm to study differences between postpartum and diestrous virgin female rats in their anxiety-related behaviors, and this difference is influenced by dams’ recent contact with pups and GABAA receptor neurotransmission particularly affected by activity at the picrotoxin site.

Keywords: anxiety, black-white box, fear, GABA, lactation, maternal behavior

Female rodents undergo complex behavioral changes during the peripartum period, including decreased fear- and anxiety-related behaviors that may be prerequisite for dams’ heightened maternal responsiveness to neonates and aggression toward intruders (Fleming and Leubke, 1981; Hard and Hansen, 1985). Recently parturient females exhibit less anxiety behavior in many paradigms when compared to pregnant or virgin females (for reviews see Lonstein, 2007; Neumann, 2003), but the light-dark box has been surprisingly under-utilized to study postpartum anxiety given its simplicity and frequent use for studying anxiety in male rodents. Only three studies have compared the light-dark box behaviors of postpartum and virgin female rodents and they report contradictory results. Lactating female house mice were shown to be less anxious than virgin females in this apparatus (Maestripieri and D’Amato; 1991), but a more recent study suggests no difference in light-dark box behavior between postpartum and virgin mice (Gammie et al., 2008). One study of female rats also found no significant difference between postpartum and diestrous virgins in light-dark box behavior (Zuluaga et al., 2005).

Convergence of results among multiple behavioral paradigms would increase assurance about the most relevant influences on postpartum anxiety, as opposed to often indefinable aspects of anxiety idiosyncratically revealed by a single paradigm (Ramos, 2008). The usefulness of such convergence, in addition to the wealth of evidence demonstrating low postpartum anxiety in most behavioral paradigms (for some exceptions see Lonstein, 2007) and discrepancies among the existing studies using light-dark boxes to compare anxiety across female reproductive states, we here re-examined the effect of motherhood on light-dark box behaviors in female rats. In a second experiment, we tested if recent contact with pups is required for dams’ reduced anxiety-related behavior in a light-dark box, as we have found in an elevated plus-maze (Figueira et al., 2008; Lonstein, 2005; Smith and Lonstein, 2008). In a final experiment, we investigated the influence of GABAA receptor activity on light-dark box behavior in both postpartum and virgin female rats. Similar to anxiety in non-postpartum animals (Millan, 2003), elevated postpartum GABAA neurotransmission is strongly implicated in dams’ low anxiety behavior in other paradigms (Hansen, 1990; Hansen et al., 1985; Miller et al., 2010). To pinpoint which GABAA receptor binding sites may be particularly involved in suppressing dams’ anxiety behavior in the light-dark box, in separate groups of subjects we targeted the GABA site with (+)-Bicuculline [(+)-Bic], the benzodiazepine site with FG-7142, and the picrotoxin site with pentylenetetrazol [PTZ].

Experiment I: Light-dark box behavior of postpartum and diestrous virgin rats

Methods

Subjects

Subjects were female Long-Evans rats, descended from rats purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN), born and raised in our colony. After weaning at 21 days of age, subjects were group-housed in clear polypropylene cages (48 × 28 × 16 cm) in groups of 2–3 female littermates, with wood shavings for bedding, a 12:12 light:dark cycle (0800 hr lights on), and food and water available ad lib. After 75 days of age, subjects for the virgin groups were rehoused with 1–2 other non-sibling female virgins, while subjects for the postpartum groups were monitored daily with a vaginal impedance meter that measures changes in electrical resistance of the vaginal walls across the estrous cycle (Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA). Females for the postpartum group found to be in proestrus were mated overnight with sexually experienced males from our colony, then rehoused in groups of 2–3 pregnant females per cage the following day. Approximately 4–5 days before the expected day of parturition, these females were singly housed. Litters were culled to contain 4 males and 4 females within 48 hr after birth. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Michigan State University.

Light-dark box testing

Behavioral testing occurred between 1200–1630 hr. Dams were tested on day 7 or 8 postpartum (n = 9) with the day of parturition assigned as day 0. Virgin females (n = 8) were gently vaginally smeared each morning and the cytology used to determine their stage of the estrous cycle; females were tested on a day of diestrus. Subjects were left undisturbed in the colony room at least 3 hrs before testing, then brought in a cage to a nearby testing room containing a light-dark box. The light-dark box was made of white and black opaque Plexiglas (20 × 30 × 30 cm light chamber, 30 × 30 × 30 cm dark chamber). The chambers were connected by a 10 × 10 cm door in the middle of the wall separating the two chambers. Animals were placed in the middle of the light chamber facing a side away from the door and then released.

A mirror was placed above the light-dark box and the images in the mirror were videotaped with a Panasonic low-light sensitive video camera connected to a Panasonic VCR in an adjacent room. Females’ behaviors were scored for 10 min with a computerized data acquisition system either while being videotaped, or the videotapes were transcribed at a later time. Ambient illumination was 624 lx in the light chamber and 3 lx the dark chamber because our previous pilot work revealed that light levels lower than this resulted in no difference between postpartum and diestrous virgin female rats in their light-dark box behavior (Miller and Lonstein, 2006). After testing, subjects were removed from the light-dark box and returned to their home cage in colony room. The apparatus was cleaned with 70% ethanol after each use and allowed to dry before the next subject was tested.

Behavioral Variables

Behaviors in the light-dark box analyzed included the duration of time spent in the light chamber, number of full-body transitions between chambers, frequency of rears in the light chamber, frequency of stretches from the dark chamber into the light chamber (at least part of the head but not all four feet in the light chamber), the latency from the beginning of testing to enter the dark chamber, and the latency to re-enter the light chamber after the first bout spent in the dark chamber (non-responders were assigned a latency of 600 s). These behaviors have all previously been measured as a reflection of anxiety in this apparatus (Costall et al 1989; Crawley, 1981; Bourin and Hascoët 2003; De Angelis 1992; Hascoët and Bourin 1998). Because the frequency of rears in the light chamber is easily confounded by the duration of time animals spend in the light chamber, the frequency of rears made in the light chamber was standardized by the duration of time each subject spent in that chamber (number of rears/duration of time in light x 100).

Data Analyses

Data were data were first examined for normality using Shapiro-Wilk’s tests. Normally distributed data were analyzed with independent t-tests comparing postpartum and virgin rats. Variables not normally distributed were log transformed and normality confirmed on the transformed data prior to analyses with t-tests. In all cases, statistical significance was indicated by p < 0.05.

Results

Postpartum females spent significantly more time in the light chamber of the light-dark box than did diestrous virgins (t(15) = 2.21, p < 0.05; Figure 1). Dams also tended to transition between chambers significantly more often than did virgins (Table 1). The frequency of rears standardized by the duration of time subjects spent in the light did not differ between groups. Groups also did not differ in the frequency of stretches from the dark chamber to the light chamber, their latencies to initially enter the dark chamber, or in the other behavioral variables recorded (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Duration of time spent in the light chamber of a light-dark box by diestrous virgin (VIR – white bars) and postpartum (PP – black bars) rats. Data not normally distributed so log-transformed prior to analysis. Untransformed means ± SEMs are shown. *p < 0.05 on the transformed data.

Table 1.

Anxiety-related behaviors of unmanipulated diestrous virgin and postpartum female rats tested in a light-dark box.

| Virgin | Postpartum | t(15) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of chamber transitions# | 3 ± 1 | 10 ± 2 | 1.93 | 0.07 |

| Frequency of rears/Time spent in light chamber*# | 14 ± 8 | 14 ± 2 | 0.49 | 0.63 |

| Frequency of stretches from dark to light | 24 ± 3 | 27 ± 3 | 0.57 | 0.58 |

| Latency to enter dark chamber (s)# | 2 ± 1 | 5 ± 3 | 0.21 | 0.83 |

| Latency to re-enter light chamber (s)# | 314 ± 107 | 178 ± 82 | 0.81 | 0.43 |

Includes responders only.

Not normally distributed so log-transformed prior to analysis. Non-transformed means ± SEM are shown in all cases. Statistical significance was indicated by p < 0.05.

Experiment II: Influence of recent litter contact on light-dark box behavior of postpartum rats

Methods

Subjects

Subjects were postpartum female rats from our colony raised and housed as described in Experiment I.

Light-Dark Box Testing

Testing followed the same procedure as Experiment I, except that one group of postpartum females (n = 15) had their pups removed and placed in an incubator set at 34°C (nest temperature) 4 hrs before testing. We previously found this increases postpartum female rats’ anxiety-related behavior in an elevated plus-maze (Figueira et al., 2008; Lonstein, 2005; Smith and Lonstein, 2008). The other group of dams (n = 16) were left alone in their home cages and allowed continual contact with their pups until the time of testing. Separated litters were returned to their dams immediately after testing.

Data Analyses

Based on our previous results demonstrating that separation from pups significantly increases dams’ anxiety-related behaviors (Figueira et al., 2008; Lonstein, 2005; Smith and Lonstein, 2008), data from this experiment were analyzed using one-tailed t-tests. Variables that were not normally distributed were log transformed before analysis. Statistical significance was indicated by p < 0.05.

Results

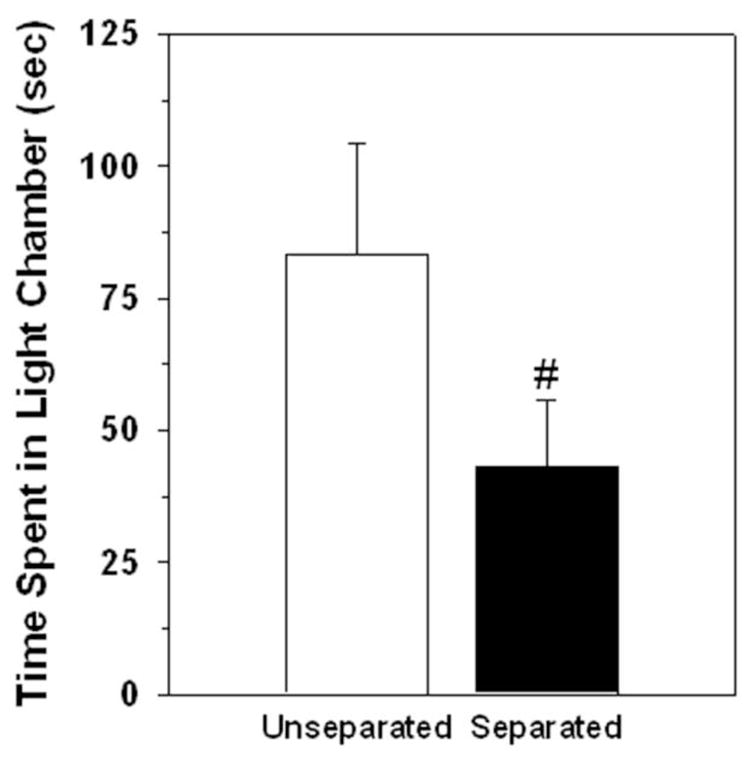

Dams that were separated from their pups four hours before testing spent approximately half as much time in the light chamber compared to unseparated dams (t(29) = 1.79 p < 0.05; Figure 2). Separated dams also exhibited significantly fewer chamber transitions than did dams allowed continual access to their pups before testing (Table 2). The groups did not differ in the other behavioral variables recorded (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Duration of time (Mean ± SEM) spent in the light chamber of a light-dark box by postpartum rats that were either allowed access to their litters (Unseparated) or separated from their litters 4 hours before testing (Separated). Data not normally distributed so log-transformed prior to analysis. Untransformed means ± SEMs are shown. + p < 0.05, one-tailed on the transformed data.

Table 2.

Anxiety-related behaviors (Mean ± SEM) of postpartum rats separated from pups or not four hr before testing in a light-dark box.

| Unseparated | Separated | t(29) | p+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of chamber transitions | 10 ± 2 | 7 ± 1 | 1.78 | 0.04 |

| Frequency of rears/Time spent in light chamber* | 15 ± 2 | 13 ± 2 | 0.60 | 0.28 |

| Frequency of stretches from dark to light | 24 ± 2 | 24 ± 3 | 0.04 | 0.48 |

| Latency to enter dark chamber (s)# | 6 ± 5 | 1 ± 0 | 0.60 | 0.28 |

| Latency to re-enter light chamber (s)# | 155 ± 56 | 140 ± 52 | 0.02 | 0.49 |

Includes responders only.

Not normally distributed so log-transformed prior to analysis. Non-transformed means ± SEM are shown in all cases.

One-tailed tests; statistical significance was indicated by p < 0.05.

Experiment III: Effects of GABAA receptor antagonism on light-dark box behavior of postpartum and diestrous virgin rats

Methods

Subjects

Subjects were housed as described in Experiment I, with the exception that virgins in this experiment were singly housed at least 3 days before testing. We previously found no effect of single vs. group housing on diestrous virgin females’ behavior in an elevated plus-maze; in both cases virgins display more anxiety-related behaviors than do postpartum females (Lonstein, unpublished data).

Drugs

All drugs were purchased from Sigma (USA). (+)-Bicuculline [(+)-Bic] (2 or 4 mg/kg) was prepared similar to that described by McDonald et al. (2008). The drug was first dissolved in 45 μL acetic acid, 150 μL propylene glycol and 200 μL NaOH (50%). The solution volume was then brought up to 0.8 mL with saline, pHed to 5.0, and then the volume raised to 1 mL. This provided a reliably clear solution. FG-7142 (10 or 25 mg/kg) was dissolved in physiological saline with 1 drop of TWEEN-80 added per 2 mL solution, which was stirred and then sonicated for approximately 10 min before use. Pentylenetetrazol (PTZ) (10 or 20 mg/kg) was dissolved in physiological saline. Doses used were based on those previously observed to affect anxiety-related behaviors in laboratory rodents (Atack et al., 2005; Evans and Lowry, 2007; File et al., 1987; Hansen et al., 1985; Nicolas and Prinssen, 2006; Pellow and File, 1986; Dalvi and Rodgers, 1996; Zarrindast et al., 2001). The injected volume of all solutions was 1 ml/kg body weight. Control animals for each drug received the corresponding vehicle in which the drug was dissolved. To avoid additional handling and stress on the day of testing subjects’ body weights were obtained 1–4 days before testing.

Light-Dark Box Testing

Light-dark box testing was conducted similar to Experiment I above. Subjects were briefly removed from their home cage within the colony room, received an intraperitoneal injection of vehicle or one of the three drugs, returned to their home cage, and brought to the nearby testing room 15 min later; this time of testing after injection was used for all three drugs to facilitate comparison across the them and is consistent with the window of action for these drugs after intraperitoneal injection (e.g., Cole et al., 1995; Miller et al., 2010; Uehara et al., 2005). There were 11–16 animals in each group (see Tables 3–5 for sample sizes).

Table 3.

Anxiety-related behaviors (Mean ± SEM) of diestrous virgin and postpartum female rats tested in a light-dark box after IP injection of vehicle or (+)-Bic.

| Virgin | Postpartum | Significant Effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle (n = 16) | (+)-Bic2 mg (n = 12) | (+)-Bic 4 mg (n = 12) | Vehicle (n = 13) | (+)-Bic 2 mg (n = 15) | (+)-Bic 4 mg (n = 12) | ||

| Frequency of chamber transitions# | 4 ± 1 | 2 ± 0 | 6 ± 2 | 11 ± 1 | 7 ± 1 | 7 ± 1 | State, Dose |

| Frequency of rears/Time spent in light chamber* | 11 ± 1 | 13 ± 4 | 13 ± 2 | 14 ± 0 | 13 ± 1 | 14 ± 2 | ---------- |

| Frequency of stretches from dark to light | 25 ± 3 | 21 ± 2 | 26 ± 4 | 31 ± 2 | 24 ± 3 | 23 ± 3 | ---------- |

| Latency to enter dark chamber (s)# | 6 ± 3 | 3 ± 2 | 7 ± 4 | 0 ± 0 | 2 ± 2 | 2 ± 1 | State |

| Latency to re-enter the light chamber (s)# | 418 ± 60 | 466 ± 69 | 245 ± 81 | 86 ± 45 | 228 ± 71 | 196 ± 71 | State, state x Dose |

Includes responders only.

Not normally distributed so log-transformed prior to analysis. Non-transformed means ± SEM are shown in all cases. Statistical significance was indicated by p < 0.05. See text for additional statistical details.

Table 5.

Anxiety-related behaviors (Mean ± SEM) of diestrous virgin and postpartum female rats tested in a light-dark box after IP injection of vehicle or PTZ.

| Virgin | Postpartum | Significant Effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle (n = 12) | PTZ 10 mg (n = 10) | PTZ 20 mg (n = 12) | Vehicle (n = 14) | PTZ 10 mg (n = 14) | PTZ 20 mg (n = 12) | ||

| Frequency of chamber transitions# | 3 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | 12 ± 2a | 9 ± 1a | 2 ± 1b | State, Dose, State x Dose |

| Frequency of rears/Time spent in light chamber* | 9 ± 4 | 8 ± 3 | 3 ± 2 | 15 ± 1 | 10 ± 2 | 6 ± 6 | Dose |

| Frequency of stretches from dark to light# | 23 ± 4 | 16 ± 5 | 9 ± 2 | 29 ± 3 | 28 ± 2 | 9 ± 3 | State, Dose |

| Latency to enter dark chamber (s) # | 2 ± 1 | 4 ± 1 | 3 ± 2 | 1 ± 0 | 2 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | State |

| Latency to re-enter the light chamber (s) # | 389 ± 76 | 429 ± 86 | 459 ± 66 | 114 ± 46 | 94 ± 22 | 492 ± 65 | State, Dose |

Includes responders only.

Not normally distributed so log-transformed prior to analysis. Non-transformed means ± SEM are shown in all cases. Statistical significance was indicated by p < 0.05. Groups with different superscript letters significantly differ, one-way ANOVA within reproductive state, p < 0.05. See text for additional statistical details.

Data Analyses

Data were analyzed with a series of separate 2 (reproductive state) × 3 (drug dose) ANOVAs for each of the drugs tested. Significant omnibus ANOVAs were followed by Fisher’s LSD post-hoc tests comparing individual groups. Data that were not normally distributed according to Shapiro-Wilk’s tests were log transformed prior to analyses with the ANOVAs. In cases of significant interactions, one-way ANOVAs were used to compare groups within reproductive state. Statistical significance was indicated by p < 0.05. One subject was eliminated from the 20 mg PTZ postpartum group after a Dixon’s Q test revealed it as an outlier for the duration of time spent in the light chamber (p < 0.01).

Results

(+)-Bicuculline

There was a significant main effect of reproductive state on the duration of time spent in the light chamber, with dams spending significantly more time in the light chamber than did virgins (F(1,74) = 10.10, p < 0.002; Figure 3). There was no significant main effect of (+)-Bic (F(2,74) = 2.51, p > 0.09), or interaction between reproductive state and (+)-Bic (F(2,74) = 1.33, p > 0.27), on the duration of time spent in the light chamber.

Figure 3.

Duration of time (Mean ± SEM) spent in the light chamber by diestrous virgin (VIR – white bars) and postpartum (PP – black bars) rats that received IP injection of vehicle, 2 mg (+)-Bic, or 4 mg (+)-Bic. Data not normally distributed so log-transformed prior to analysis. Untransformed means ± SEMs are shown. *Significant main effect of reproductive state on the transformed data, p < 0.05.

There was also a significant main effect of reproductive state on the frequency of chamber transitions such that dams transitioned more often than virgins (F(1,74) = 18.29, p < 0.0001; Table 3). There was a main effect of (+)-Bic on chamber transitions (F(2,74) = 3.18, p < 0.05) and post-hoc analysis revealed that vehicle-injected subjects transitioned more often than subjects receiving 2 mg of (+)-Bic. There was no significant interaction between reproductive state and (+)-Bic on the number of chamber transitions (F(2,74) = 2.18, p > 0.12).

There was a significant main effect of reproductive state on the frequency of rears standardized for the duration of time subjects spent in the light chamber, with dams rearing more often than did virgins (F(1,72) = 4.83, p < 0.04). There was no significant effect of (+)-Bic (F(2,72) = 1.52, p > 0.22) (Table 3) or interaction between these factors (F(2,72) = 2.01, p > 0.13).

There were also no main effects of reproductive state (F(1,74) = 0.10, p > 0.75) or (+)-Bic (F(2,74) = 2.16, p > 0.12) on the frequency of stretches from the dark chamber to the light chamber (Table 3). There was also no significant interaction between these factors (F(2,74) = 0.91, p > 0.41).

The latency to re-enter the light chamber after spending time in the dark chamber was significantly shorter in dams than in virgins (F(1,74) = 13.76, p < 0.0005; Table 3) but there was no main effect of (+)-Bic (F(2,74) = 1.67, p > 0.19). There was a significant interaction between reproductive state and (+)-Bic on this measure (F(2,74) = 4.42, p < 0.02), but analysis within reproductive state revealed that (+)-Bic only marginally reduced the latency in virgins at the 4 mg/kg dose (one way ANOVA - F(2,37) = 2.54, p = 0.09) and had no effect in dams (one way ANOVA - F(2,37) = 1.40, p > 0.25).

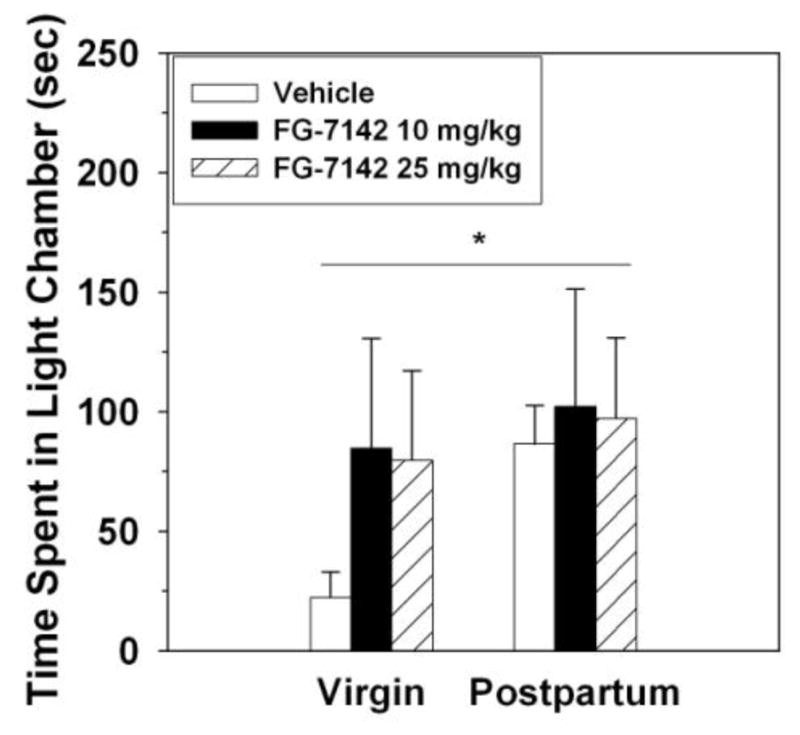

FG-7142

There was a main effect of reproductive state (F(1,80) = 10.23, p < 0.003), but not FG-7142 (F(2,80) = 0.08, p > 0.92) and no interaction between these factors (F(2,80) = 1.09, p > 0.34), on the duration of time females spent in the light chamber (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Duration of time spent in the light chamber by diestrous virgin (VIR – white bars) and postpartum (PP – black bars) rats that received IP injection of vehicle, 10 mg FG-7142, or 25 mg FG-7142. Data not normally distributed so log-transformed prior to analysis. Untransformed means ± SEMs are shown. *Significant main effect of reproductive state on the transformed data, p < 0.05.

The frequency of chamber transitions was significantly higher in dams than in virgins (F(1,80) = 19.20, p < 0.0001; Table 4). There was no significant main effect of FG-7142 (F(2,80) = 1.03, p > 0.36) and no significant interaction between reproductive state and FG-7142 on the number of transitions (F(2,80) = 1.12, p > 0.37).

Table 4.

Anxiety-related behaviors (Mean ± SEM) of diestrous virgin and postpartum female rats tested in a light-dark box after IP injection of vehicle or FG-7142.

| Virgin | Postpartum | Significant Effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle (n = 12) | FG-7142 10 mg (n = 16) | FG-7142 25 mg (n = 17) | Vehicle (n = 15) | FG-7142 10 mg (n = 12) | FG-7142 25 mg (n = 14) | ||

| Frequency of chamber transitions# | 4 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | 4 ± 1 | 10 ± 1 | 6 ± 1 | 8 ± 2 | State |

| Frequency of rears/Time spent in light chamber* | 9 ± 3 | 11 ± 3 | 10 ± 2 | 12 ± 1 | 10 ± 2 | 9 ± 1 | ---------- |

| Frequency of stretches from dark to light# | 16 ± 4 | 14 ± 3 | 20 ± 4 | 32 ± 2 | 20 ± 4 | 27 ± 4 | Dose |

| Latency to enter dark chamber (s) # | 4 ± 2 | 50 ± 37 | 11 ± 4 | 1 ± 0 | 11 ± 7 | 7 ± 6 | ---------- |

| Latency to re-enter the light chamber (s) # | 431 ± 67 | 309 ± 75 | 338 ± 69 | 103 ± 39 | 135 ± 64 | 301 ± 65 | State |

Includes responders only.

Not normally distributed so log-transformed prior to analysis. Non-transformed means ± SEM are shown in all cases. Statistical significance was indicated by p < 0.05. See text for additional statistical details.

There were no significant main effects of reproductive state (F(1,80 = 2.35, p > 0.12) or FG-7142 (F(2,80) = 0.27, p > 0.76), and no interaction between these factors (F(2,80) = 1.58, p > 0.21), on the frequency of rears standardized for the amount of time subjects spent in the light chamber (Table 4).

There were no significant main effect of reproductive state (F(1,80) = 1.92, p > 0.16) on the frequency of stretches made from the dark chamber to the light chamber. There was a significant effect of FG-7142, though (F(2,80) = 7.01, p < 0.002), with the lowest dose reducing them compared to vehicle. There was no significant interaction between these factors (F(2,80) = 0.46, p > 0.63) these stretches (Table 4).

The latency to re-enter the light chamber after the first bout of time spent in the dark chamber was shorter in dams than in virgins (F(1,80) = 10.97, p < 0.002), but this was not affected by FG-7142 (F(2,80) = 1.52, p > 0.22) and there was no significant interaction between factors on this measure (F(2,80) = 3.11, p > 0.05; Table 4).

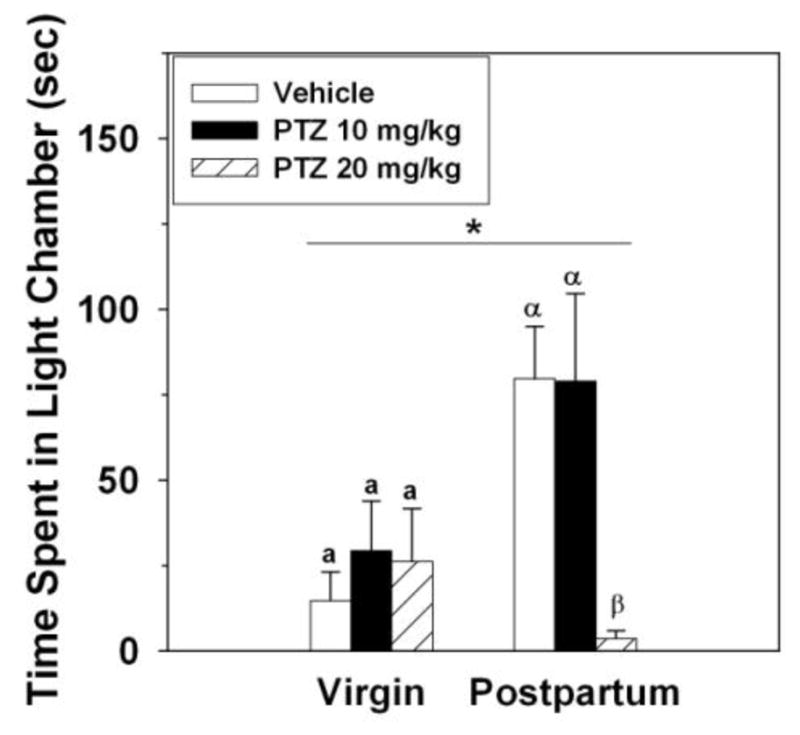

Pentylenetetrazol

Dams spent significantly more time in the light chamber compared to virgins (F(1,68) = 11.05, p < 0.002; Figure 5). PTZ significantly affected the time females spent in the light chamber, with the 20 mg dose decreasing it compared to 10 mg of PTZ or saline (F(2,68) = 8.05, p < 0.0008; Figure 5). This was qualified by a significant interaction between reproductive state and dose of PTZ (F(2,68) = 8.59, p < 0.0006), such that dams receiving the 20 mg dose of PTZ spent less time in the light chamber compared to other groups of dams (one way ANOVA - F(2,37) = 4.98, p < 0.02), while PTZ had no effect on the duration of time virgins spent in the light chamber (one way ANOVA - F(2,31) = 0.35, p > 0.71) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Duration of time (Mean ± SEM) spent in the light chamber by diestrous virgin (VIR – white bars) and postpartum (PP – black bars) rats that received IP injection of vehicle, 10 mg PTZ, or 20 mg PTZ. *Significant main effect of reproductive state on the transformed data, p < .05. Different Roman or Greek letters above bars within each reproductive state indicate significant difference among groups, post-hoc p < 0.05.

Postpartum females made significantly more chamber transitions than did virgins (F(1,68) = 21.28, p < 0.0001) and this was also affected by PTZ such that the 20 mg dose significantly reduced chamber transitions (F(2,68) = 9.46, p < 0.0003). Similar to the duration of time spent in the light chamber, there was an interaction between reproductive state and PTZ (F(2,68) = 8.66, p < 0.0005), with 20 mg PTZ reducing chamber transitions in dams (one way ANOVA - F(2,37) = 11.66, p < 0.0001) but not virgins (one way ANOVA F(2,31) = 0.03, p > 0.96) (Table 5).

Reproductive state did not influence on the frequency of rears standardized for the duration of time subjects spent in the light chamber (F(1,41) = 2.08, p > 0.15). There was, however, a significant main effect of PTZ with 20 mg significantly reducing rears compared to the 10 mg dose or saline (F(2,41) = 4.71, p < 0.02). There was no significant interaction between reproductive state and PTZ on the standardized frequency of rears (F(2,41) = 0.31, p > 0.73; Table 5).

The was also no main effect of reproductive state (F(1,68) = 2.34, p > 0.13) on the frequency of stretches from the dark chamber to the light chamber. There was, however, a significant main effect of PTZ, with 20 mg significantly decreasing stretches from the dark chamber (F(2,68) = 12.57, p < 0.0001). There was no significant interaction between factors on frequency of stretching from the dark chamber (F(2,68) = 2.76, p > 0.07; Table 5).

There was a main effect of reproductive state on the latency to re-enter the light chamber after the first bout of time spent in the dark chamber, with dams re-entering the light chamber faster than did virgins (F(1,68) = 10.86, p < 0.002). PTZ also had an effect with subjects given 20 mg of PTZ taking significantly longer to re-enter the light chamber than did those receiving either 10 mg PTZ or saline (F(2,68) = 4.80, p < 0.02). There was no significant interaction between reproductive state and PTZ on this latency measure (F(2,68) = 2.33, p > 0.10) (Table 5).

Discussion

The present results demonstrate that: 1) postpartum rats display fewer anxiety-related behaviors in a light-dark box than do diestrous virgins, 2) separating mothers from their pups 4 hours before testing in a light-dark box increases anxiety-related behaviors compared to dams not separated from their litter before testing, and 3) (+)-Bic and FG-7142 each produced some minor anxiogenic effects in both dams and diestrous virgins, but the picrotoxin site ligand PTZ was potently and selectively anxiogenic in postpartum females.

Methodological considerations

Our results demonstrate that postpartum rats display behaviors reflecting low anxiety in a light-dark box - including more time spent in the light chamber, more transitions between chambers, and in some of the experiments a greater readiness to reenter the light chamber (Chaouloff et al., 1997; Crawley and Goodwin, 1980; Ramos et al., 1997) - when compared to diestrous virgins. These results are consistent with a great deal of previous research using other behavioral paradigms to compare anxiety across reproductive states in female rats (Lonstein, 2007). However, the results from the three previous studies examining how postpartum state impacts behavior in a light-dark box are inconsistent. Similar to our findings, Maestripieri and D’Amato (1991) found that postpartum mice spend more time in the light chamber of a light-dark box than do virgin females. In contrast, Gammie and colleagues (2008) found no significant change in the behavior of female mice tested in a light-dark box during pregnancy and through early lactation. Zuluaga and colleagues (2005) also found no significant differences between postpartum and diestrous virgin rats in their light-dark box behavior. Although our focus here is on the light-dark box, postpartum and virgin females rats have also sometimes been reported to not differ in their behavior in an elevated plus maze (Boccia and Pedersen, 2001; Mezzacappa et al., 2003; Neumann et al., 1998), an open field (Stern et al., 1973), and for defensive burying (Fernandez-Guasti et al., 1998, 2001; Picazo & Fernández-Guasti, 1993).

Considerable inter-laboratory differences in testing procedures may help explain contradictions among studies comparing anxiety between virgin and postpartum rats (Lonstein, 2007). Relevant to the now four studies of postpartum rodents in the light-dark box, different strains of mice (Cook et al., 2001; Mathis et al., 1994; Rodgers and Cole, 1993) and rats (Commissaris et al., 1996; Rex et al., 1996; Schmitt and Hiemke, 1998; Shepard and Myers, 2008) differ in their anxiety. This makes it is difficult to compare results obtained from Swiss outbred mice (Mastripieri and D’Amato, 1991) with those from C57BL/6J inbred mice (Gammie et al., 2008), or between Wistar (Zuluaga et al., 2005) and Long-Evans (present study) rats. Second, the intensity of the ambient light greatly affects behavior in the light-dark box and other anxiety paradigms (Bourin and Hascoët, 2003; Hogg, 1996; Violle et al., 2009). In our pilot work, we found that differences between postpartum and diestrous virgin rats in light-dark box behavior only emerged when illumination on the light chamber was at least ~600 lx (Miller and Lonstein, 2006). Below that level, neither group found the light chamber particularly aversive. Third, the chamber in which subjects begin the light-dark box test alters their behavior (Chaouloff et al., 1997). Zuluaga and colleagues (2005) and Gammie et al., (2008) started their tests with subjects placed in the dark chamber and found no effect of postpartum state, while we and Maestripieri and D’Amato (1991) started subjects in the light chamber and found reproductive state differences. In fact, we have data showing that postpartum female rats spend less time in the light chamber if they begin the test in the dark chamber (43 ± 26 sec in light) than if they are initially placed in the light chamber (165 ± 42 sec in light) (Miller and Lonstein, unpublished). Fourth, whether or not females were repeatedly tested could also help explain discrepancies between the studies (Bertoglio and Carobrez, 2000; Nosek et al., 2008; Rodgers and Shepard, 1993). Lastly, stage of the estrous cycle virgins were in at testing could be relevant because some laboratories find that cycling females are less anxious or fearful when circulating ovarian hormone levels are high (Frye et al., 2000; Llaneza and Frye, 2009; Marcondes et al., 2001; Mora et al., 1996; Toufexis, 2007; Zuluaga et al., 2005). Related to this is the possibility that a few days of brief handling during vaginal smearing (typically ~10 sec/day) altered the anxiety behavior of the diestous virgin females in our experiments. This remains to be examined experimentally but seems unlikely to underlie differences between our groups because both cycling females that are not smeared each day (Hard and Hansen, 1985; Toufexis et al., 1999) and smeared each day (Fleming and Leubke, 1981; Lonstein, 2005; Miller et al., 2010) are relatively anxious compared to postpartum females. Furthermore, ovariectomized female rats that are presumably not smeared each day are as anxious as cycling females smeared daily (Fernandez-Guasti and Picazo, 1992; Marcondes et al., 2001; Mora et al., 1996; Zuluaga et al., 2005).

Offspring Contact Influences Light-Dark Box Behavior

The hormones of pregnancy and parturition are necessary for the onset of a suite of behavioral changes in female rats (including maternal behavior, elevated aggression, anxiolysis) but these behaviors are maintained thereafter by physical interactions with offspring (Stern, 1996; Lonstein, 2005; Lonstein and Miller, 2007). This is supported by data demonstrating that postpartum ovariectomy or adrenalectomy, or prepartum hypophysectomy, have little effect on anxiety in mother rats (Hansen, 1990; Lonstein, 2005). However, recent infant contact is required for the postpartum suppression of anxiety when assessed with an elevated plus-maze (Figueira et al., 2008; Lonstein, 2005; Lonstein and Smith, 2008; Neumann, 2003). This conclusion is supported by the results from Experiment II, showing that absence of the litter for 4 hours before testing increases dams’ anxiety-related behaviors in a light-dark box. The importance of infant touch, rather than the hormones of pregnancy or lactation, for suppressing maternal anxiety is further evidenced by the partial blunting of fear and anxiety behaviors in nulliparous rats induced to act maternally through repeated exposure to neonates (Agrati et al., 2008; Ferreira et al., 2002). In both parous and nulliparous mothers, infant contact probably suppresses emotional behaviors through increased GABA released while females interact with the litter (Qureshi et al., 1987; Lonstein and Miller, 2008).

It is important to note that the effect of litter removal on the duration of time dams spent in the light chamber in Experiment II was only significant using a one-tailed t-test. We previously observed a statistically stronger effect of litter removal when dams were tested in an elevated plus maze, but comparing the present results and those of Experiment II from Lonstein (2005) using an plus-maze reveals that the magnitude of the separation effect is almost identical between studies (separated dams show ~50% decrease in the duration of time spent in the more aversive part of the apparatus). Behavior in a light-dark box and an elevated plus maze are sometimes strongly correlated (Henderson et al., 2004; Ramos, 2008), but it’s also been found that the light-dark box is less sensitive than the elevated plus maze to some manipulations (Biala and Kruk; 2007; Hascoët and Bourin, 1998; McCool and Chappell, 2007; Ramos, 2008; Zuluaga, 2005) and this may also be true for how litter contact affects mothers’ anxiety behavior.

GABAA Receptor Influences on Light-Dark Box Behavior

The number of neurochemicals working together to suppress anxiety in dams with recent contact with pups is probably vast, but it is not surprising that inhibitory GABA systems are involved. Dams and diestrous virgins do not differ in GABAA or benzodiazepine receptor binding within the neural anxiety network (Miller and Lonstein, 2011), but central GABA release rises when dams interact with pups and falls when pups are removed (Qureshi et al., 1987). Some functional implications of this rise in GABA release are revealed by the increased freezing in response to an acoustic stimulus in dams treated with FG-7142 and decreased punished drinking in dams given PTZ (Hansen et al., 1985; Hansen, 1990).

We here expand upon these findings by demonstrating that GABAA receptor inhibition particularly in postpartum female rats can, depending on the GABAA antagonist, increase anxiety-related behaviors in a light-dark box. More specifically, neither GABA site antagonism with (+)-Bicuculline nor benzodiazepine site inverse agonism with FG-7142 greatly affected females’ behavior in the light-dark box, but blocking the GABAA receptor chloride ion channel with the picrotoxin site ligand PTZ greatly affected numerous anxiety-related behaviors and especially did so in dams. Because PTZ did not affect females’ latencies to their first transition from the light to the dark chamber, its anxiogenic effect is not secondary to any gross locomotor deficits; still, the issue of whether PTZ simultaneously altered both dams’ anxiety and motor activity warrants further examination because PTZ at 20–30 mg/kg doses has been seen to either have no effect on (Zienowicz et al., 2007) or reduce locomotion (File, 1984; File and Lister, 1984) in laboratory rats. In contrast to the postpartum females, we found that PTZ had little effect in diestrous virgins. This could be due to a ceiling effect in the high-anxiety virgins, but also possibly because dams and virgins differ in sensitivity to some anxiety-modulating drugs (see Fernandez-Guasti et al., 1998, 2001; Ferreira et al., 2000).

The general ineffectiveness of (+)-Bicuculline or FG-7142 in both dams and virgins was probably not due to our choice of doses, which were in the range previously observed to affect anxiety-related behaviors in laboratory rodents (Atack et al., 2005; Evans and Lowry, 2007; File et al., 1987; Hansen et al., 1985; Nicolas and Prinssen, 2006; Pellow and File, 1986; Dalvi and Rodgers, 1996; Zarrindast et al., 2001). Many GABAA receptor modulators inconsistently affect anxiety in male rats (Millan, 2003) and such effects might depend on the particular behavioral tests used (Nazar et al., 1997). For example, FG-7142 can be intrinsically anxiogenic in male mice, but not when assessed with a light-dark box (Crawley et al., 1984). Similarly, we previously reported that a 4 mg/kg dose of (+)-Bicuculline is anxiogenic when dams are tested with an elevated plus-maze (Miller et al., 2010), but it was not in the present study. Lastly, while we found that PTZ is much more anxiogenic than FG-7142 in the light-dark box, it is much less effective than FG-7142 on dams’ freezing in response to a burst of noise (Hansen et al., 1985). Such paradigm-specific effects are not unexpected and may attest to how these drugs differentially affect anxiety behavior depending on the animals’ reproductive state (Fernandes et al., 1999).

PTZ binds to the picrotoxin site found within the chloride channel of GABAA receptors (Bali and Akabas, 2007; Huang et al., 2001). When the picrotoxin site is bound by PTZ or similar ligands, and GABA dissociates from its binding site, the ion channel is slower to reopen (Bali and Akabas, 2007). PTZ may have had even stronger anxiogenic effects than the other antagonists we used - which competitively bind to sites outside the channel pore - because PTZ both blocks the chloride channel and slows its reopening. Because the higher dose of PTZ potently increased anxiety behavior in dams but not virgins, the picrotoxin site may deserve particular attention in future studies of how increased GABAA receptor activity contributes to the postpartum suppression of anxiety.

Research Highlights.

Present study reexamines use of light-dark box for evaluation of anxiety-related behaviors in diestrous virgin and postpartum female rats. Existing literature using this paradigm with female rats is inconsistent.

Results were that diestrous virgin and postpartum group did differ in measures of anxiety behaviors. Differences were affected by dam’s recent contact with the litter and drugs modulating GABAA receptor activity (particularly the picrotoxin site).

These results help establish the light-dark box as a useful paradigm that can detect differences in anxiety behaviors among diestrous virgin and postpartum female rats.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by NICHD grant #HD057962 to JSL and a dissertation completion fellowship from Michigan State University to SMM.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agrati D, Zuluaga MJ, Fernández-Guasti A, Meikle A, Ferreira A. Maternal condition reduces fear behaviors but not the endocrine response to an emotional threat in virgin female rats. Horm Behav. 2008;53:232–40. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atack JR, Hutson PH, Collinson N, Marshall G, Bentley G, Moyes C, Cook SM, Collins I, Wafford K, McKernan RM, Dawson GR. Anxiogenic properties of an inverse agonist selective for α3 subunit-containing GABAA receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;144:357–366. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bali M, Akabas MH. The location of a closed channel gate in the GABAA receptor channel. J Gen Physiol. 2007;129:145–159. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoglio LJ, Carobrez AP. Previous maze experience required to increase open arms avoidance in rats submitted to the elevated plus-maze model of anxiety. Behav Brain Res. 2000;108:197–203. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biala G, Kruk M. Amphetamine-induced anxiety-related behavior in animal models. Pharmacol Rep. 2007;59:636–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boccia ML, Pedersen CA. Brief vs. long maternal separations in infancy: contrasting relationships with adult maternal behavior and lactation levels of aggression and anxiety. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2001;26:657–72. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourin M, Hascöet M. The mouse light/dark box test. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;463:55–65. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01274-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaouloff F, Durand M, Mormede P. Anxiety- and activity-related effects of diazepam and chlordiazepoxide in the rat light/dark and dark/light tests. Behav Brain Res. 1997;85:27–35. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(96)00160-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole BJ, Hillmann M, Seidelmann D, Klewer M, Jones GH. Effects of benzodiazepine receptor partial inverse agonists in the elevated plus maze test of anxiety in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 1995;121:118–26. doi: 10.1007/BF02245598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook MN, Williams RW, Flaherty L. Anxiety-related behaviors in the elevated zero-maze are affected by genetic factors and retinal degeneration. Behav Neurosci. 2001;115:468–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commissaris RL, Verbanac JS, Markovska VL, Altman HJ, Hill TJ. Anxiety-like and depression-like behavior in Maudsley reactive (MR) and non-reactive (NMRA) rats. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1996;20:491–501. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(96)00012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costall B, Jones BJ, Kelly ME, Naylor RJ, Tomkins DM. Exploration of mice in a black and white test box: validation as a model of anxiety. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1989;32:777–85. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley JN. Neuropharmacologic specificity of a simple animal model for the behavioral actions of benzodiazepines. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1981;15:695–9. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(81)90007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley JN, Skolnick P, Paul SM. Absence of intrinsic antagonist actions of benzodiazepine antagonists on an exploratory model of anxiety in the mouse. Neuropharmacology. 1984;23:531–7. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(84)90026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalvi A, Rodgers RJ. GABAergic influences on plus-maze behaviour in mice. Psychopharmacology. 1996;128:380–97. doi: 10.1007/s002130050148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Angelis L. The anxiogenic-like effects of pentylenetetrazole in mice treated chronically with carbamazepine or valproate. Meth Find Exp Clinl Pharmacol. 1992;14:767–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AK, Lowry CA. Pharmacology of the β-carboline FG-7142, a partial inverse agonist at the benzodiazepine allosteric site of the GABAA receptor: Neurochemical, neurophysiological, and behavioral effects. CNS Drug Rev. 2007;13:475–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2007.00025.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes C, González MI, Wilson CA, File SE. Factor analysis shows that female rat behaviour is characterized primarily by activity, male rats are driven by sex and anxiety. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;64:731–8. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Guasti A, Picazo O. Changes in burying behavior during the estrous cycle: effect of estrogen and progesterone. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1992;17:681–9. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(92)90027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Guasti A, Ferreira A, Picazo O. Diazepam, but not buspirone, induces similar anxiolytic-like actions in lactating and ovariectomized Wistar rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;70:85–93. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00586-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Guasti A, Picazo O, Ferreira A. Blockade of the anxiolytic action of 8-OH-DPAT in lactating rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;59:45–50. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00392-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira A, Picazo O, Uriarte N, Pereira M, Fernández-Guasti A. Inhibitory effect of buspirone and diazepam, but not of 8-OH-DPAT, on maternal behavior and aggression. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;66:389–96. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira A, Pereira M, Agrati D, Uriarte N, Fernández-Guasti A. Role of maternal behavior on aggression, fear and anxiety. Physiol Behav. 2002;77:197–204. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00845-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueira RJ, Peabody MF, Lonstein JS. Oxytocin receptor activity in the ventrocaudal periaqueductal gray modulates anxiety-related behavior in postpartum rats. Behav Neurosci. 2008;122:618–28. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.3.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- File SE. Behavioural effects of pentylenetetrazole reversed by chlordiazepoxide and enhanced by RO 15–1788. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1984;326:129–31. doi: 10.1007/BF00517309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- File SE, Lister RG. Do the reductions in social interaction produced by picrotoxin and pentylenetetrazole indicate anxiogenic actions? Neuropharmacology. 1984;23:793–6. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(84)90113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming AS, Luebke C. Timidity prevents the virgin female rat from being a good mother: Emotionality differences between nulliparous and parturient females. Physiol Behav. 1981;27:863–868. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(81)90054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Petralia SM, Rhodes ME. Estrous cycle and sex differences in performance on anxiety tasks coincide with increases in hippocampal progesterone and 3alpha,5alpha-THP. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;67:587–96. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00392-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammie SC, Seasholtz AF, Stevenson SA. Deletion of corticotropin-releasing factor binding protein selectively impairs maternal, but not intermale aggression. Neuroscience. 2008;157:502–12. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen S. Mechanisms involved in the control of punished responding in mother rats. Horm Behav. 1990;24:186–97. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(90)90004-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen S, Ferreira A. Effects of bicuculline infusions in the ventromedial hypothalamus and amygdaloid complex on food intake and affective behavior in mother rats. Behav Neurosci. 1986;100:410–5. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.100.3.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen S, Ferreira A, Selart ME. Behavioural similarities between mother rats and benzodiazepine treated non maternal animals. Psychopharmacology. 1985;86:344–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00432226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hard E, Hansen S. Reduced fearfulness in the lactating rat. Physiol Behav. 1985;35:641–643. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(85)90155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hascöet M, Bourin M. A new approach to the light/dark test procedure in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;60:645–653. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(98)00031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson ND, Turri MG, DeFries JC, Flint J. QTL analysis of multiple behavioral measures of anxiety in mice. Behav Gen. 2004;34:267–293. doi: 10.1023/B:BEGE.0000017872.25069.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg S. A review of the validity and variability of the elevated plus-maze as an animal model of anxiety. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996;54:21–30. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang RQ, Bell-Horner CL, Dibas MI, Covey DF, Drew JA, Dillon GH. Pentylenetetrazole-induced inhibition of recombinant γ-aminobutyric acid type (GABAA) receptors: Mechanism and site of action. J Pharmacol Exp Therap. 2001;298:986–995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llaneza DC, Frye CA. Progestogens and estrogen influence impulsive burying and avoidant freezing behavior of naturally cycling and ovariectomized rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;93:337–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonstein JS. Reduced anxiety in postpartum rats requires recent physical interactions with pups, but is independent of suckling and peripheral sources of hormones. Horm Behav. 2005;47:241–255. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonstein JS. Regulation of anxiety during the postpartum period. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2007;28:115–141. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonstein JS, Miller SM. Infant touch, neurochemistry, and postpartum anxiety. In: Bridges RS, editor. The Parental Brain. Academic Press; 2008. pp. 145–173. [Google Scholar]

- Maestripieri D, D’Amato FR. Anxiety and maternal aggression in house mice (Mus musculus): a look at interindividual variability. J Comp Psychol. 1991;105:295–301. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.105.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcondes FK, Miguel KJ, Melo LL, Spadari-Bratfisch RC. Estrous cycle influences the response of female rats in the elevated plus-maze test. Physiol Behav. 2001;74:435–40. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00593-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathis C, Paul SM, Crawley JN. Characterization of benzodiazepine-sensitive behaviors in the A/J and C57BL/6J inbred strains of mice. Behav Genet. 1994;24:171–80. doi: 10.1007/BF01067821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCool BA, Chappell A. Strychnine and taurine modulation of amygdala-associated anxiety-like behavior is ‘state’ dependent. Behav Brain Res. 2007;178:70–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald LM, Sheppard WF, Staveley SM, Sohal B, Tattersall FD, Hutson PH. Discriminative stimulus effects of tiagabine and related GABAergic drugs in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2008;197:591–600. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1077-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzacappa ES, Tu AY, Myers MM. Lactation and weaning effects on physiological and behavioral response to stressors. Physiol Behav. 2003;78:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00889-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ. The neurobiology and control of anxious states. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;70:83–244. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SM, Lonstein JS. Lactation and ambient light level, but not the anxiogenic agent FG-7142, affect anxiety in the light-dark box test. Society for Behavioral Neuroendocrinology Abstracts. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Miller SM, Lonstein JS. Autoradiographic analysis of GABAA receptor binding in the brain anxiety network of postpartum and non-postpartum laboratory rats. Brain Res Bull. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.05.013. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SM, Piasecki CC, Peabody MF, Lonstein JS. GABAA receptor antagonism in the ventrocaudal periaqueductal gray increases anxiety in the anxiety-resistant postpartum rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;95:457–65. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora S, Dussaubat N, Díaz-Véliz G. Effects of the estrous cycle and ovarian hormones on behavioral indices of anxiety in female rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1996;21:609–20. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(96)00015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazar M, Jessa M, PlaŸnik A. Benzodiazepine-GABAA receptor complex ligands in two models of anxiety. J Neur Trans. 1997;104:733–746. doi: 10.1007/BF01291890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann ID. Brain mechanisms underlying emotional alterations in the peripartum period in rats. Depress Anx. 2003;17:111–121. doi: 10.1002/da.10070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann ID, Johnstone HA, Hatzinger M, Liebsch G, Shipston M, Russell JA, Landgraf R, Douglas AJ. Attenuated neuroendocrine responses to emotional and physical stressors in pregnant rats involve adenohypophysial changes. J Physiol. 1998;508:289–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.289br.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas LB, Prinssen EP. Social approach-avoidance behavior of a high-anxiety strain of rats: effects of benzodiazepine receptor ligands. Psychopharmacology. 2006;184:65–74. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0233-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosek K, Dennis K, Andrus BM, Ahmadiyeh N, Baum AE, Solberg Woods LC, Redei EE. Context and strain-dependent behavioral response to stress. Behav Brain Funct. 2008;4:23. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-4-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellow S, File SE. Anxiolytic and anxiogenic drug effecst on exploratory activity in an elevated plus-maze: A novel test of anxiety in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1986;24:525–529. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(86)90552-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picazo O, Fernández-Guasti A. Changes in experimental anxiety during pregnancy and lactation. Physiol Behav. 1993;54:295–9. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90114-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi GA, Hansen S, Sodersten P. Offspring control of cerebrospinal fluid GABA concentrations in lactating rats. Neurosci Lett. 1987;75:85–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos A. Animal models of anxiety: do I need multiple tests? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:493–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos A, Berton O, Mormède P, Chaouloff F. A multiple-test study of anxiety-related behaviours in six inbred rat strains. Behav Brain Res. 1997;85:57–69. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(96)00164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos A, Pereira E, Martins GC, Wehrmeister TD, Izidio GS. Integrating the open field, elevated plus maze and light/dark box to assess different types of emotional behaviors in one single trial. Behav Brain Res. 2008;193:277–288. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rex A, Sondern U, Voigt JP, Franck S, Fink H. Strain differences in fear-motivated behavior of rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996;54:107–11. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers RJ, Cole JC. Influence of social isolation, gender, strain, and prior novelty on plus-maze behaviour in mice. Physiol Behav. 1993;54:729–36. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90084-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt U, Hiemke C. Strain differences in open-field and elevated plus-maze behavior of rats without and with pretest handling. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;59:807–11. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00502-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard JD, Myers DA. Strain differences in anxiety-like behavior: association with corticotropin-releasing factor. Behav Brain Res. 2008;186:239–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CD, Lonstein JS. Contact with infants modulates anxiety-generated c-fos activity in the brains of postpartum rats. Behav Brain Res. 2008;190:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern JM. Somatosensation and maternal care in Norway rats. In: Rosenblatt JS, Snowden CT, editors. Parental care: evolution, mechanisms, and adaptive significance. Advances in the study of behavior. Vol. 25. San Diego: Academic; 1996. pp. 243–294. [Google Scholar]

- Stern JM, Goldman L, Levine S. Pituitary-adrenal responsiveness during lactation in rats. Neuroendocrinology. 12:179–91. doi: 10.1159/000122167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toufexis D. Region- and sex-specific modulation of anxiety behaviours in the rat. J Neuroendocrinol. 2007;19:461–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2007.01552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toufexis DJ, Rochford J, Walker CD. Lactation-induced reduction in rats’ acoustic startle is associated with changes in noradrenergic neurotransmission. Behav Neurosci. 1999;113:176–84. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.113.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehara T, Sumiyoshi T, Matsuoka T, Tanaka K, Tsunoda M, Itoh H, Kurachi M. Enhancement of lactate metabolism in the basolateral amygdala by physical and psychological stress: role of benzodiazepine receptors. Brain Res. 2005;1065:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Violle N, Balandras F, Le Roux Y, Desor D, Schroeder H. Variations in illumination, closed wall transparency and/or extramaze space influence both baseline anxiety and response to diazepam in the rat elevated plus-maze. Behav Brain Res. 2009;203:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrindast MR, Rostami P, Sadeghi-Hariri M. GABAA but not GABAB receptor stimulation induces antianxiety profile in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;69:9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00518-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zienowicz M, Wisłowska-Stanek A, Lehner M, Taracha E, Skórzewska A, et al. Fluoxetine attenuates the effects of pentylenetetrazol on rat freezing behavior and c-Fos expression in the dorsomedial periaqueductal gray. Neurosci Lett. 2007;414:252–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuluaga MJ, Agrati D, Pereira M, Uriarte N, Fernandez-Guasti A, Ferreira A. Experimental anxiety in the black and white model in cycling, pregnant and lactating rats. Physiol Behav. 2005;84:279–86. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]