Abstract

Background

Engagement refers to the act of being occupied or involved with an external stimulus. In dementia, engagement is the antithesis of apathy.

Objective

The Comprehensive Process Model of Engagement was examined, in which environmental, person, and stimulus characteristics impact the level of engagement of persons with dementia.

Methods

Participants were 193 residents of 7 Maryland nursing homes. All participants had a diagnosis of dementia. Stimulus engagement was assessed via the Observational Measure of Engagement. Engagement was measured by duration, attention, and attitude to the stimulus. 25 stimuli were presented, which were categorized as live human social stimuli, simulated social stimuli, inanimate social stimuli, a reading stimulus, manipulative stimuli, a music stimulus, task and work-related stimuli, and two different self-identity stimuli.

Results

All stimuli elicited significantly greater engagement in comparison to the control stimulus. In the multivariate model, music significantly increased engagement duration, while all other stimuli significantly increased duration, attention, and attitude. Significant environmental variables in the multivariate model that increased engagement were: use of the long introduction with modeling (relative to minimal introduction), any level of sound (most especially moderate sound), and the presence of between 2 to 24 people in the room. Significant personal attributes included MMSE scores, ADL performance and clarity of speech, which were positively associated with higher engagement scores.

Conclusions

Results are consistent with the Comprehensive Process Model of Engagement. Person attributes, environmental factors, and stimulus characteristics all contribute to the level and nature of engagement, with a secondary finding being that exposure to any stimulus elicits engagement in persons with dementia.

Keywords: nursing home residents, dementia, engagement, environment, personal characteristics, stimuli

Nursing home residents spend the majority of their time unoccupied and not engaged in any meaningful activity (1,2). Such understimulation can have especially negative effects for residents with dementia as it magnifies the apathy, boredom, depression, and loneliness that often accompany the progression of dementia (3,4).

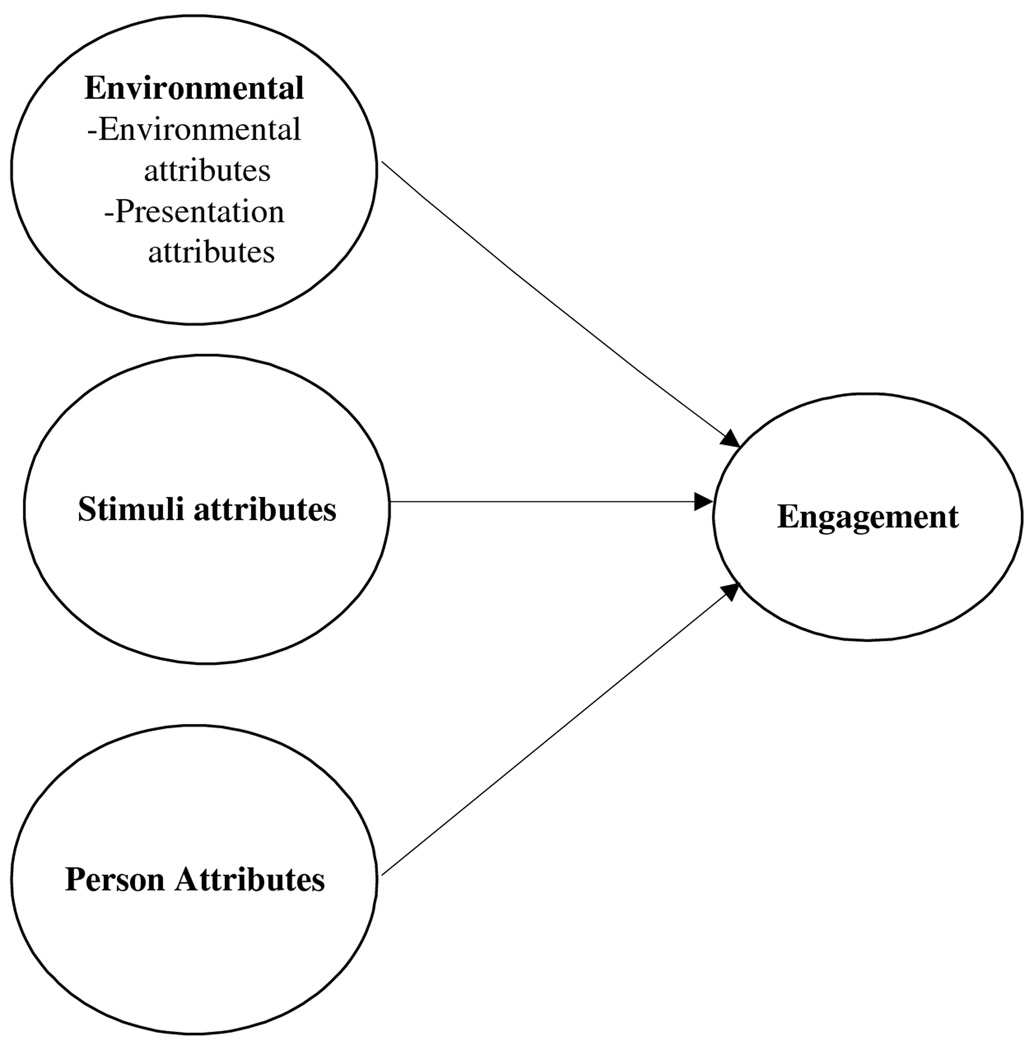

Engagement refers to the act of being occupied or involved with an external stimulus, which includes concrete objects, activities, and other persons. The Comprehensive Process Model of Engagement (5) aims to explain the factors that affect engagement in persons with dementia and postulates that engagement with stimuli is influenced by environmental characteristics, personal characteristics, and stimulus attributes. Engagement in turn results in a change in affect that influences the manifestation of behavior problems (Figure 1). In this paper, we examine the impact of environmental, personal, and stimulus characteristics on the level of engagement. While we have published papers which examined sections of the model, in this paper we tie the different portions together and analyze their relative impact concurrently.

Figure 1.

The Comprehensive Process Model of Engagement

An individual’s environment can adversely or positively influence engagement quality. We recently reported that nursing home residents with dementia were engaged with stimuli more often in an environment with normal lighting, moderate levels of sound and with small groups of people (i.e., 4 to 9) (6). Previously, Foster and Valentine (7) found that persons with dementia recalled answers better when there was some room noise versus none and when there was music playing versus other background noise.

Personal characteristics, such as demographics, cognitive functioning, medical status, and functional status (including hearing and vision) have been found to influence engagement in persons with dementia (8). For example, female gender, higher cognitive and better ADL functioning have been linked with longer engagement with stimuli (8) and with longer participation in activities (9–12). Decreased social interactions have been linked with pain (13) and visual and hearing impairment (11). Residents with poor hearing tended to refuse stimuli more often than those with adequate hearing (8).

Stimulus characteristics can significantly affect engagement quality. Cohen-Mansfield and Werner (14) found that one-on-one social interaction with a research assistant was a potent stimulus. However, staff and family are not always available to engage nursing home residents in social contact, and alternate forms of social contact, such as simulated interaction (audiotaped or videotaped conversation with a relative) (15,16;17) have been found to increase interest and reduce negative behaviors. Positive results have also been seen with robotic animals (18) and animal-based social stimuli (19). Furthermore, stimuli customized to individual interests and capabilities have been found to decrease neuropsychiatric behaviors and increase activity engagement (20).

In this paper, we develop estimates for portions of our Comprehensive Process Model of Engagement. Specifically, using Generalized Estimated Equations (GEE) methodology, we examine the separate and combined effects of stimulus attributes, environmental attributes, and person attributes. Through the GEE analyses, we thus provide a description of a global model of engagement. We hypothesized that the environmental, personal, and stimulus attributes each have independent effects on engagement.

Methods

Participants

Participating nursing homes approached potential participants based on their fit with inclusion criteria. Our inclusion criterion was a confirmed diagnosis of dementia. Exclusion criteria were: the resident had an accompanying diagnosis of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, had no dexterity or movement in either hand, could not be seated in a chair/wheelchair, had a MMSE score of 23 or above, or was younger than 60 years. Once consent was obtained for eligible participants, background information was retrieved and the MMSE administered. The final sample of participants included 193 residents of 7 Maryland nursing homes, and all had a diagnosis of dementia.

Procedure

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the CES Life Communities. Informed consent was obtained for all study participants from their relatives or other responsible parties (21). Twenty-five predetermined engagement stimuli were presented to participants over a three-week period (approximately 4 stimuli per day). Stimuli were categorized as: live human social stimuli, which included a real baby, and one-on-one socializing with a research assistant; simulated social stimuli, which included a life-like (“real”) baby doll, a robotic animal, and a video respite ™ (a commercially available video of a person talking to the person with dementia; the video often includes singing and asking the viewer to join in 22,23); inanimate social stimuli which included a childish-looking doll and a plush animal; a real pet which involved visits with a real dog, a reading stimulus, which included a large print magazine; manipulative stimuli, which included a squeeze ball, tetherball, expanding sphere, activity pillow, building blocks, a fabric book, a wallet (males) or purse (females), and a puzzle; a music stimulus, which included listening to recorded music; task and work-related stimuli, including arranging flowers, coloring with markers, stamping envelopes, folding towels, and an envelope sorting task; and two different personalized stimuli, based on the study participant’s self-identity.

Stimuli were presented in random order with either a long introduction with modeling or a short, minimal introduction. If the participant refused the engagement stimulus, the research assistant removed it. Engagement trials took place between 9:30 am – 12:30 pm and between 2 pm – 5:30 pm, as these are the times that residents are not usually occupied with care activities at the nursing home. Individual engagement trials were separated by a washout period of at least 5 minutes.

Dependent variables

Engagement: Observational Measurement of Engagement (OME)

The OME (5) was developed to assess the levels of engagement of persons with intellectual disabilities, and measured the four outcome variables of engagement: duration, attention, attitude, and refusal. Duration refers to the amount of time that the participant was occupied or involved with a stimulus and was measured in seconds. Attention to the stimulus occurs when a study participant is focused on the stimulus (i.e., eye tracking, visual scanning, facial, motoric, or verbal feedback, or eye contact), and is measured on a four-point scale: (1) not attentive, (2) somewhat attentive, (3) attentive, and (4) very attentive. Attitude toward the stimulus may be observed by positive or negative facial expression, verbal content or physical movement toward the stimulus, and was measured on a seven-point scale: (1) very negative, (2) negative, (3) somewhat negative, (4) neutral, (5) somewhat positive, (6) positive, and (7) very positive. Rate of refusal refers to whether or not an individual rejected a stimulus, and was recorded as ‘yes’ or ‘no.’

OME data were recorded through direct observations using specially designed software installed on a handheld computer, the Palm One Zire 31™. Intraclass correlation averaged 0.78 for the engagement outcome variables. A baseline observation was completed each day before stimulus presentation. One research assistant presented the stimulus and a second research assistant, who remained unobtrusive, observed the participant’s reaction and engagement with the stimulus via the OME, entering the data directly onto a Palm Pilot Zire31™.

Independent variables

Environmental attributes

Setting and presentation

Background noise, lighting, and number of persons in proximity were obtained via the environment portion of the Agitation Behavior Mapping Instrument (ABMI) (24). Background noise was recorded as: 1=none, 2=low, 3=moderate, 4=high, 5=very high. Lighting was recorded as 1=bright, 2=normal, 3=dark. Number of persons in close proximity to the participant was recorded as: 1=zero, 2=one person, 3=two persons, 4=three persons, 5=from four to nine persons, 6=from ten to twenty-four persons, 7=twenty-five or more persons.

Modeling

Each stimulus was presented twice during the study (but not on the same day), once with an explanation and demonstration of how the stimulus should be used, and once without such modeling.

Personal Attributes

Demographic and medical data were retrieved from the residents’ charts at the nursing homes, including information about gender, age, marital status, medical conditions from which the resident suffers, and a list of medications taken. Data assessed using the MDS (25) included those pertaining to activities of daily living (ADL; utilizing a scale from 1 to 5, where 5=maximum dependence), speech clarity (1=no speech, 2=unclear speech, 3=clear speech), making oneself understood (1=rarely/never understood, 2=sometimes understood, 3=usually understood, 4=understood), vision (recorded on a 5-point scale where 1=severely impaired, 5=adequate), and hearing (4-point scale where 1=highly impaired, 4=hears adequately).

The MMSE (26) was administered to each participant by a research assistant trained with regard to standardized administration and scoring procedures.

In order to determine activities of interest to the participant, we interviewed the resident whenever possible and also conducted a telephone interview with a close relative using the Self-Identity Questionnaire (SIQ) (27). The SIQ examines four types of role-identity: professional, family-role, leisure activities, and personal attributes. We calculated the number of leisure activities that had been named as a past interest for each study participant.

Stimulus attributes

As previously mentioned, each participant was presented with 25 different predetermined engagement stimuli over a three-week period (approximately 4 stimuli per day). The stimuli were categorized according to the stimulus attributes of live human social stimuli, simulated social stimuli, inanimate social stimuli, a real pet, a reading stimulus, manipulative stimuli, task and work-related stimuli, and two different self-identity stimuli that were matched to each participant’s past identity with respect to occupation, hobbies, or interests. For example, an individual with an interest in astronomy could be given a book on stargazing and constellations, and a participant who worked as a chef might watch cooking videos. Self-identity stimuli therefore varied across participants.

Statistical methods

The three measures of engagement, attention, attitude and duration, were treated as ordinal variables with 4, 5 and 6 categories, respectively. Although engagement duration could have been treated as a continuous variable, it had a high proportion of zero values and therefore was categorized using the zeros as the first category and quintiles of the positive values as the other 5 categories.

A proportional odds model with repeated measurements for the different stimuli was then fitted using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE), executed by the Genmod Procedure (28) with the option “Repeated” in SAS (version 9.13), assuming a multinomial distribution for the outcome variables and the cumulative logit link. The GEE approach allowed us to examine the effects of different stimuli within the same model taking account of the within-person correlations between the outcomes following each stimulus. The explanatory variables were: type of stimulus (10 nominal categories), introduction (long vs. short), age, gender, marital status, ethnicity, education, number of diagnoses, number of medications, number of psychotropic medications, MMSE, ADL, clarity of speech, count of past interest, vision, hearing, sound, lighting, and number of people present. Since for each stimulus, the attention and attitude scores were assessed according to (a) the highest value displayed and (b) the most typical value, an additional covariate was included in the models (“highest”: yes vs. no) to distinguish between these two types of assessment.

The process of building the multivariate model started with fitting a univariate model (for attention and attitude, it was adjusted for the covariate “highest”). Explanatory variables that were significant at the 20% level were entered into a backward elimination procedure in which the least significant variables were eliminated sequentially until all remaining variables were significant at the 5% level. This constituted the final multivariate model. The effects of stimuli were compared with each other using Tukey’s pairwise multiple comparisons (29).

A separate model for refusals (yes versus no) was also built, using a proportional odds model with repeated measurements, and assuming a binomial distribution for the outcome and a logit link. Since refusal of the control stimulus was impossible by definition, these observations were excluded from the analysis.

Prior to the analysis we compared the different nursing homes on level of engagement across all conditions using analyses of variance (ANOVA). None of the engagement variables differed across the nursing homes (F-test on 6 and 186 df = .44, .28, .22, p = .85, .95, and .97 for duration, attention and attitude respectively). Therefore nursing home was not included in the main analysis.

Results

151 participants were female (78%), and age averaged 86 years, (range= 60–101). The majority of participants were Caucasian (81%), followed by African-Americans (10%). Most participants were widowed (65%) or married (20%). In terms of education, 18% had less than high school education, 45% had high school education, and the rest had obtained either trade school or partial college education (12%), a bachelor’s degree (13%) or graduate degree (12%). ADL performance, which was obtained through the Minimum Data Set (MDS) (25) averaged 3.6 (1-‘independent’ to 5-‘complete dependence’). Cognitive functioning, as assessed via the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (26), averaged 7.2 (SD=6.3, range=0–23). Participants had an average of 6.7 medical diagnoses.

Table 1 provides median levels for the engagement variables for the different stimuli. Findings from the GEE univariate analyses for the 3 measures of engagement are presented in Table 2, and those from the univariate analyses of refusal are shown in Table 3. The results of multivariate analyses for the 3 measures of engagement revealed that all types of stimuli were associated with significantly increased odds for higher engagement scores in comparison to the control stimulus (see Table 4). Based on the odds ratios, the most effective stimulus was one-on-one socializing with a research assistant, followed by the self-identity stimuli. Other stimulus categories influenced attention, particularly those pertaining to Simulated social, Task/work, Reading, Inanimate social, Real pet, and Manipulative. Significant personal attributes were: higher levels of cognitive functioning, ADL, and speech function. Significant environmental attributes were: a long introduction, moderate levels of sound, and having 2–24 people around (rather than either being alone or in a larger crowd).

Table 1.

Engagement by type of stimulus – median values

| Type of Stimulus | Durationa | Attentionb | Attitudec | Refusal (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 4.50 | 1.75 | 4.50 | not applicable |

| Real human | 697.50 | 3.25 | 5.50 | 0.00 |

| Self-Identity | 171.75 | 2.67 | 5.00 | 0.00 |

| Simulated soc. | 118.83 | 2.40 | 5.00 | 16.67 |

| Reading | 52.00 | 2.25 | 5.00 | 0.00 |

| Pet | 34.00 | 2.50 | 5.00 | 0.00 |

| Task/work | 112.90 | 2.40 | 4.86 | 10.00 |

| Manipulative | 92.25 | 2.32 | 4.83 | 12.50 |

| Inanimate social | 63.75 | 2.17 | 5.00 | 25.00 |

| Music | 13.50 | 1.50 | 4.50 | 0.00 |

In seconds

Scale: 1- not attentive, 2- somewhat attentive, 3- attentive, and 4- very attentive

Scale: 1- very negative, 2- negative, 3- somewhat negative, 4- neutral, 5- somewhat positive, 6- positive, and 7- very positive.

Table 2.

Results of GEE univariate analyses describing the relationships between stimulus, environmental and personal attributes and the three measures of engagement

| Duration | Attention | Attitude | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio |

Confidence interval |

P | Odds ratio |

Confidence interval |

P | Odds ratio |

Confidence interval |

P | ||

| Stimulus attributes | ||||||||||

| Type of Stimulus | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||||

| Control - refa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Real human | 37.03 | 26.06–52.62 | 12.24 | 8.86–16.91 | 15.05 | 10.71–21.16 | ||||

| Self-Identity | 5.41 | 4.14–7.07 | 4.57 | 3.41–6.14 | 4.21 | 3.12–5.68 | ||||

| Simulated soc. | 3.32 | 2.52–4.35 | 3.18 | 2.42–4.19 | 3.89 | 2.92–5.18 | ||||

| Reading | 3.16 | 2.42–4.13 | 2.97 | 2.21–3.99 | 2.42 | 1.80–3.27 | ||||

| Pet | 3.08 | 2.30–4.13 | 3.68 | 2.62–5.18 | 6.26 | 4.15–9.45 | ||||

| Task/work | 2.94 | 2.28–3.79 | 2.96 | 2.22–3.95 | 1.96 | 1.49–2.58 | ||||

| Manipulative | 2.33 | 1.83–2.96 | 2.31 | 1.78–3.00 | 1.97 | 1.52–2.54 | ||||

| Inanimate social | 2.28 | 1.74–3.00 | 2.39 | 1.79–3.18 | 2.83 | 2.12–3.78 | ||||

| Music | 1.55 | 1.17–2.06 | 0.96 | 0.72–1.29 | 1.01 | 0.75–1.37 | ||||

| Environmental Attributes | ||||||||||

| Introduction | Short - refa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Long | 1.23 | 1.16–1.30 | <0.0001 | 1.22 | 1.15–1.30 | <0.0001 | 1.29 | 1.21–1.38 | <0.0001 | |

| Sound | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||||

| None - refa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Low | 2.62 | 1.11–6.18 | 2.58 | 1.07–6.25 | 2.15 | 0.94–4.91 | ||||

| Moderate | 4.16 | 1.80–9.58 | 4.41 | 1.87–10.41 | 3.38 | 1.52–7.56 | ||||

| High | 3.09 | 1.30–7.37 | 3.06 | 1.27–7.42 | 2.48 | 1.06–5.81 | ||||

| Lighting | 0.012 | 0.0004 | 0.011 | |||||||

| Normal - refa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Bright | 0.91 | 0.63–1.31 | 0.73 | 0.50–1.05 | 0.79 | 0.56–1.13 | ||||

| Dark | 0.55 | 0.40–0.77 | 0.45 | 0.32–0.62 | 0.54 | 0.38–0.76 | ||||

| Social | 0.062 | 0.045 | 0.004 | |||||||

| 0 - refa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 1 | 1.23 | 0.93–1.63 | 1.26 | 0.94–1.68 | 1.32 | 1.00–1.75 | ||||

| 2 | 1.60 | 1.18–2.18 | 1.56 | 1.13–2.16 | 1.78 | 1.30–2.45 | ||||

| 3 | 1.46 | 1.07–1.99 | 1.52 | 1.08–2.13 | 1.55 | 1.10–2.18 | ||||

| 4–9 | 1.40 | 1.04–1.89 | 1.38 | 1.01–1.88 | 1.39 | 1.04–1.86 | ||||

| 10–24 | 1.42 | 1.10–1.84 | 1.48 | 1.12–1.95 | 1.52 | 1.17–1.98 | ||||

| 25+ | 1.03 | 0.58–1.84 | 0.97 | 0.52–1.79 | 0.83 | 0.47–1.44 | ||||

| Personal Attributes | ||||||||||

| Age | 0.631 | 0.676 | 0.397 | |||||||

| <84.05 - refa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 84.05–89.79 | 1.16 | 0.85–1.59 | 1.18 | 0.81–1.73 | 1.29 | 0.89–1.87 | ||||

| >=89.79 | 1.11 | 0.81–1.52 | 1.14 | 0.78–1.68 | 1.16 | 0.80–1.69 | ||||

| Gender | Male - refa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Female | 1.31 | 0.97–1.78 | 0.077 | 1.38 | 0.95–2.02 | 0.096 | 1.35 | 0.93–1.96 | 0.121 | |

| Marital status | Other than married - refa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Married | 0.80 | 0.59–1.09 | 0.163 | 0.71 | 0.49–1.05 | 0.091 | 0.72 | 0.50–1.05 | 0.096 | |

| Ethnicity | Not Caucasian-refa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Caucasian | 1.01 | 0.73–1.39 | 0.965 | 1.11 | 0.75–1.65 | 0.590 | 1.07 | 0.74–1.57 | 0.713 | |

| Education | Less than HS-refa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| More than HS | 1.01 | 0.77–1.33 | 0.940 | 0.95 | 0.88–1.04 | 0.270 | 0.96 | 0.88–1.04 | 0.276 | |

| # of diagnoses | 0.175 | 0.012 | 0.041 | |||||||

| <=5 - refa | 1.0 | 1.00 | 1.0 | |||||||

| 5–7 | 1.24 | 0.93–1.65 | 1.67 | 1.20–2.32 | 1.54 | 1.12–2.14 | ||||

| >7 | 1.31 | 0.96–1.79 | 1.41 | 0.96–2.06 | 1.29 | 0.89–1.88 | ||||

| MMSE | 0.042 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||||

| <3 - refa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 3–10 | 1.44 | 1.06–1.95 | 2.41 | 1.70–3.42 | 2.10 | 1.49–2.97 | ||||

| >= 10 | 1.41 | 1.01–1.97 | 3.99 | 2.80–5.68 | 3.24 | 2.28–4.60 | ||||

| ADL | 0.014 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||||

| <=1.6 - refa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 1.6–2.9 | 1.59 | 1.16–2.18 | 2.35 | 1.65–3.36 | 2.24 | 1.58–3.18 | ||||

| >2.9 | 1.38 | 1.02–1.88 | 2.75 | 1.92–3.93 | 2.49 | 1.77–3.50 | ||||

| Speech clarity | 0.025 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||||

| Clear speech - refa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Unclear speech | 0.75 | 0.58–0.97 | 0.45 | 0.32–0.63 | 0.47 | 0.35–0.64 | ||||

| No speech | 0.25 | 0.12–0.50 | 0.13 | 0.08–0.21 | 0.18 | 0.12–0.25 | ||||

| Past interest | 1.01 | 0.97–1.04 | 0.747 | 1.01 | 0.97–1.04 | 0.686 | 1.01 | 0.97–1.04 | 0.620 | |

| Vision | 0.856 | 0.518 | 0.614 | |||||||

| Adequate - refa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Impaired | 0.93 | 0.69–1.26 | 1.23 | 0.85–1.78 | 1.12 | 0.79–1.59 | ||||

| Moderately imp | 1.07 | 0.54–2.11 | 1.22 | 0.52–2.82 | 1.19 | 0.53–2.65 | ||||

| Highly impaired | 0.74 | 0.34–1.60 | 0.67 | 0.28–1.60 | 0.61 | 0.27–1.41 | ||||

| Hearing | 0.579 | 0.089 | 0.121 | |||||||

| Adequate - refa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Min. difficulty | 1.03 | 0.72–1.50 | 1.56 | 1.05–2.31 | 1.52 | 1.04–2.21 | ||||

| Special sit. & Highly impaired | 0.79 | 0.51–1.24 | 1.36 | 0.82–2.26 | 1.21 | 0.73–2.01 | ||||

| No. of meds | 1.03 | 0.99–1.07 | 0.150 | 1.05 | 1.01–1.10 | 0.023 | 1.05 | 1.01–1.09 | 0.032 | |

| No. of psychotr. Meds | 0.363 | 0.188 | 0.283 | |||||||

| 0 - refa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 1 | 0.77 | 0.52–1.14 | 0.75 | 0.47–1.19 | 0.76 | 0.48–1.18 | ||||

| 2+ | 0.77 | 0.54–1.11 | 1.03 | 0.68–1.57 | 0.97 | 0.64–1.47 | ||||

Note: Live human social stimuli included a real baby, and one-on-one socializing with a research assistant; simulated social stimuli included a life-like (“real”) baby doll, a robotic animal, and a respite video; inanimate social stimuli included a childish-looking baby doll and a plush animal.

P-values are based on Wald statistics with 1 degree of freedom for individual categories, and with k-1 degrees of freedom for the overall test of a variable with k categories.

P values under .2 are typed in bold and those variables were included in the multivariate model.

refa - the category is the reference value

Table 3.

The relationships between stimulus, environment, and personal attributes and refusal: results of GEE univariate analyses

| Refused | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio |

Confidence interval |

P | ||

| Stimulus attributes | ||||

| Type of Stimulus | <0.0001 | |||

| Real human- refa | 1.00 | |||

| Inanimate social | 10.83 | 5.42–21.63 | ||

| Simulated social | 10.03 | 5.04–19.93 | ||

| Manipulative | 8.56 | 4.35–16.85 | ||

| Task/work | 7.66 | 3.90–15.04 | ||

| Reading | 6.86 | 3.24–14.53 | ||

| Pet | 6.72 | 3.02–14.97 | ||

| Music | 6.33 | 3.13–12.80 | ||

| Identity | 5.66 | 2.76–11.63 | ||

| Environmental. Attributes | ||||

| Introduction | Short- refa | 1.00 | ||

| Long | 0.93 | 0.85–1.01 | 0.096 | |

| Personal attributes | ||||

| Age | 0.631 | |||

| <84.05- refa | 1.00 | |||

| 84.05–89.79 | 0.91 | 0.58–1.45 | ||

| >=89.79 | 0.95 | 0.61–1.48 | ||

| Gender | Male- refa | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 0.92 | 0.58–1.45 | 0.710 | |

| Marital status | Other- refa | 1.00 | ||

| Married | 0.97 | 0.61–1.54 | 0.905 | |

| Ethnicity | Other than white- refa | 1.00 | ||

| White Caucasian | 1.14 | 0.70–1.87 | 0.590 | |

| Education | Lower than HS- refa | 1.00 | ||

| More than HS | 0.71 | 0.48–1.07 | 0.097 | |

| No. of diagnoses | 0.087 | |||

| <=5- refa | 1.0 | |||

| 5–7 | 1.50 | 0.96–2.35 | ||

| >7 | 0.98 | 0.60–1.60 | ||

| MMSE | <0.0001 | |||

| <3- refa | 1.00 | |||

| 3–10 | 2.67 | 1.59–4.46 | ||

| >= 10 | 4.93 | 2.97–8.18 | ||

| ADL | 0.0009 | |||

| <=1.6- refa | 1.00 | |||

| 1.6–2.9 | 1.53 | 0.93–2.50 | ||

| >2.9 | 2.40 | 1.52–3.80 | ||

| Clarity of speech | <0.0001 | |||

| Clear speech- refa | 1.00 | |||

| Unclear speech | 0.38 | 0.24–0.59 | ||

| No speech | 0.54 | 0.10–2.79 | ||

| Count of past int. | 0.99 | 0.95–1.04 | 0.799 | |

| Vision | 0.240 | |||

| Adequate- refa | 1.00 | |||

| Impaired | 1.55 | 1.04–2.31 | ||

| Moderately impaired | 1.18 | 0.45–3.10 | ||

| Highly impaired | 0.98 | 0.44–2.18 | ||

| Hearing | 0.006 | |||

| Adequate- refa | 1.00 | |||

| Min. difficulty | 1.82 | 1.18–2.80 | ||

| Special situations & highly impaired | 2.23 | 1.32–3.76 | ||

| No. of medications | 1.03 | 0.98–1.08 | 0.215 | |

| No. of psychotropic medications | 0.017 | |||

| 0 - refa | 1.00 | |||

| 1 | 1.18 | 0.67–2.08 | ||

| 2+ | 1.88 | 1.13–3.12 | ||

Note: Refusal could not be compared to control conditions. The reference stimulus is therefore the one with the lowest refusal rate, i.e., real human. The environmental attributes of sound, light, and number of persons in the environment were not measured when the person refused the stimulus.

Note: Live human social stimuli included a real baby, and one-on-one socializing with a research assistant; simulated social stimuli included a life-like (“real”) baby doll, a robotic animal, and a respite video; inanimate social stimuli included a childish-looking baby doll and a plush animal.

Note: Most environmental attributes were not measured in cases of refusal.

Note: P-values are based on Wald statistics with 1 degree of freedom for individual categories, and with k-1 degrees of freedom for the overall test of a variable with k categories.

P values under .2 are typed in bold and those variables were included in the multivariate model.

refa - the category is the reference value

Table 4.

Results of GEE multivariate analyses (the global model) describing the relationships between stimulus, environmental and personal attributes and the three measures of engagement

| Duration | Attention | Attitude | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio |

Confidence interval |

Odds ratio |

Confidence interval |

Odds ratio |

Confidence interval |

||

| Stimulus attributes | |||||||

| Type of Stimulus | Control - refa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Real humana | 78.87*** | 53.14–117.06 | 14.56*** | 10.20–20.79 | 16.62*** | 11.57–23.86 | |

| Identityb | 13.71*** | 10.24–18.36 | 6.24*** | 4.53–8.60 | 5.33*** | 3.86–7.36 | |

| Simulated socialc | 9.39*** | 7.18–12.27 | 3.93*** | 2.95–5.23 | 4.61*** | 3.45–6.16 | |

| Task/work | 7.12*** | 5.41–9.37 | 3.77*** | 2.76–5.14 | 2.27*** | 1.70–3.02 | |

| Reading | 7.01*** | 5.26–9.34 | 3.77*** | 2.74–5.17 | 2.81*** | 2.05–3.85 | |

| Inanimate social | 5.70*** | 4.37–7.45 | 3.05*** | 2.24–4.13 | 3.51*** | 2.60–4.75 | |

| Pet | 5.57*** | 3.98–7.80 | 3.97*** | 2.73–5.78 | 6.63*** | 4.35–10.12 | |

| Manipulative | 5.19*** | 4.05–6.64 | 2.96*** | 2.24–3.92 | 2.38*** | 1.82–3.11 | |

| Musica | 2.72*** | 2.00–3.72 | 1.05 | 0.76–1.44 | 1.10 | 0.79–1.53 | |

| Environmental attributes | |||||||

| Introduction | Short - refa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Long | 1.13** | 1.05–1.21 | 1.10** | 1.02–1.18 | 1.12** | 1.03–1.21 | |

| Sound | None - refa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Low | 3.02* | 1.15–7.92 | 3.02* | 1.10–8.26 | 2.27 | 0.91–5.66 | |

| Moderate | 4.49** | 1.72–11.70 | 4.93** | 1.80–13.50 | 3.36** | 1.36–8.33 | |

| High | 3.24* | 1.20–8.75 | 3.55* | 1.27–9.96 | 2.50 | 0.96–6.47 | |

| Social | 0 - refa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 1 | 1.23 | 0.95–1.6 1 | 1.27 | 0.97–1.65 | 1.32* | 1.02–1.71 | |

| 2 | 1.47* | 1.09–1.99 | 1.40* | 1.02–1.92 | 1.53** | 1.11–2.11 | |

| 3 | 1.55** | 1.13–2.13 | 1.56** | 1.12–2.17 | 1.52* | 1.08–2.15 | |

| 4–9 | 1.58** | 1.18–2.12 | 1.56** | 1.17–2.08 | 1.58*** | 1.22–2.05 | |

| 10–24 | 1.53** | 1.18–1.98 | 1.58*** | 1.20–2.07 | 1.62*** | 1.24–2.12 | |

| 25+ | 1.24 | 0.78–2.00 | 1.27 | 0.79–2.03 | 1.03 | 0.67–1.58 | |

| Personal attributes | |||||||

| MMSE | <3 - refa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 3–10 | 1.83*** | 1.31–2.54 | 1.96*** | 1.40–2.74 | 1.67** | 1.18–2.36 | |

| >=10 | 2.87*** | 2.03–4.05 | 3.29*** | 2.29–4.71 | 2.59*** | 1.79–3.75 | |

| ADL | <=1.6 - refa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 1.6–2.9 | 1.88*** | 1.38–2.55 | 2.05*** | 1.49–2.80 | 1.95*** | 1.42–2.68 | |

| >2.9 | 1.67** | 1.21–2.29 | 1.88*** | 1.37–2.58 | 1.78*** | 1.30–2.43 | |

| Clarity of speech | Clear speech - refa | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Unclear speech | 0.67* | 0.49–0.92 | 0.69* | 0.51–0.95 | 0.68* | 0.50–0.93 | |

| No speech | 0.24*** | 0.17–0.34 | 0.25*** | 0.18–0.35 | 0.30*** | 0.21–0.44 | |

Note: P-values are based on Wald statistics with 1 degree of freedom for individual categories, and with k-1 degrees of freedom for the overall test of a variable with k categories.

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001

p<.05 for all comparisons with other stimuli (Tukey’s pairwise comparison test)

p<.05 for all comparisons with other stimuli, except for simulated social and pet stimuli with respect to attitude (Tukey’s pairwise comparison test)

p<.05 for comparisons with all other stimuli except reading for duration; for comparisons with manipulative and music stimuli for attention; and for comparisons with reading, task, manipulative and music stimuli for attitude (Tukey’s pairwise comparison test)

Note. The following were not candidates for the multivariate analysis since they were not significant (P<0.2) in the univariate model: age, race, education, count of past interest, vision, hearing (duration), no. of psychotropic medications (duration & attitude).

The following variables entered the backward elimination procedure and were excluded from the final model due to non-significance: gender, marital status, no. of diagnosis, hearing, lighting, no. of medications, no. of psychotropic medications (attention).

Note: Live human social stimuli included a real baby, and one-on-one socializing with a research assistant; simulated social stimuli included a life-like (“real”) baby doll, a robotic animal, and a respite video; inanimate social stimuli included a childish-looking baby doll and a plush animal.

refa - the category is the reference value

Multivariate analyses for refusal revealed that in comparison with the real human stimulus, the remaining 8 stimuli were associated with significantly increased odds for refusal (see Table 5). The inanimate social stimuli, ranking 6 out of 9 in engagement duration, and 5 in terms of attitude, was the most frequently rejected, with simulated social stimuli, ranking as the 3rd most engaging type of stimulus, also ranking as 2nd for refusal. Moreover, we found that study participants with the highest level of cognitive functioning (MMSE ≥ 10) had the highest refusal rates, odds ratio 4.86, and risk ratio of 3.59, i.e., they were 3.6 times more likely to refuse in comparison to participants with a MMSE of 3 or less.

Table 5.

The relationship between stimulus, environment, and personal attributes and refusal: results of GEE multivariate analyses

| Refused | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio |

Confidence interval |

||

| Stimulus type | Real human - refa | 1.00 | |

| Inanimate social | 11.69*** | 5.80–23.53 | |

| Simulated social | 10.85*** | 5.43–21.69 | |

| Manipulative | 9.09*** | 4.59–17.99 | |

| Task/work | 7.88*** | 4.00–15.55 | |

| Reading | 7.10*** | 3.30–15.26 | |

| Pet | 6.94*** | 3.05–15.79 | |

| Identity | 5.93*** | 2.85–12.33 | |

| Music | 6.62*** | 3.24–13.49 | |

| MMSE | <3 - refa | 1.00 | |

| 3–10 | 2.63*** | 1.53–4.54 | |

| >=10 | 4.71*** | 2.71–8.18 | |

| Speech clarity | Clear speech - refa | 1.00 | |

| Unclear speech | 0.56* | 0.35–0.89 | |

| No speech | 1.81 | 0.32–10.21 | |

| # psychotropic Medications | |||

| 0 - refa | 1.00 | ||

| 1 | 1.28 | 0.72–2.26 | |

| 2+ | 1.78* | 1.08–2.93 |

Note: P-values are based on Wald statistics with 1 degree of freedom for individual categories, and with k-1 degrees of freedom for the overall test of a variable with k categories.

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001

Note: The following were not candidates for the multivariate analysis since they were not significant (P>0.2) in the univariate model: age, gender, marital status, race, count of past interest, vision, no. of medications.

The following variables entered the backward elimination procedure and were excluded from the final model due to non-significance: introduction, education, no. of diagnoses, ADL, hearing.

refa - the category is the reference value

A comparison of the univariate and multivariate models shows that several variables, such as number of diagnoses, number of medications, and light were significant at the .05 level in the univariate analysis, but were eliminated in the multivariate analysis, probably due to co-linearity with other variables.

Discussion

The overarching finding of the present study is that it is indeed a combination of environmental characteristics, personal attributes, and stimulus qualities that affects engagement in persons with dementia. While previous publications generally showed the impact of one type of influence on engagement, we find here that their combination affects engagement. Additionally, it is clear that exposure to any stimulus is preferable to no stimulation. The most potent stimuli were from the live human category and stimuli based on the study participant’s self-identity. Environmental variables that increased engagement were the use of a long introduction with modeling (relative to minimal introduction), any level of sound (especially, moderate sound), and the presence of between 2 to 24 people in the room. Personal attributes related to engagement included higher cognitive and functional status as well as greater clarity of speech. Refusal was also related to higher cognitive functioning and was higher with less socially acceptable stimuli.

Our finding that social stimuli (especially one-on-one interaction) have the most dramatic effect on engagement duration, attention and attitude is congruent with previous studies that reported significant results with animal-based social stimuli on engagement (19), and Simulated Presence Therapy (16). We also found the two different self-identity stimuli used in our study were highly effective in increasing the measures of engagement. Previously, a study that examined the involvement of persons with dementia in activities tapping their most salient self-identity, resulted in a significant increase in interest, pleasure, involvement in activities, and orientation and a decrease in agitated behaviors (27). In a paper focusing only on the efficacy of different types of stimuli and using other statistical methods, we explore the relative impact of the different types of stimuli on engagement (30).

The results regarding personal attributes indicate that engagement is highly related to different aspects of cognitive and functional status. The fact that engagement is significantly higher among those with higher levels of cognitive function is especially striking in view of the fact that higher cognitive function was also significantly related to higher refusal rates. The levels of engagement manifested by those with higher cognitive function are so much higher than those with low cognitive function that the difference is significant even when refusal is taken into account, as is the case in the measure of duration (where refusal is coded as 0 duration).

The findings regarding the personal attribute of hearing require clarification. In the univariate analyses, highly impaired hearing corresponds to a reduced level of engagement for duration (partly explained by the high refusal rate as seen in those with hearing impairment). Surprisingly, attention and attitude have an increased, albeit marginally significant, risk ratio for the hearing impaired. It is possible that the reason for this is the relationship between a designation of impaired hearing on the MDS and higher levels of cognitive function. (In order to check this we examined the MMSE of those designated as hearing adequately with those designated as having any impairment (means: 6.6 and 9.0 respectively, t(185)=2.3, p<.05). Plausible reasons for this relationship are: a) hearing impairment is under-detected in persons with advanced dementia (31), so these, like so many of the rest of the results, are a reflection of cognitive function, and b) a potential selection bias, where persons who are relatively cognitively functional will be institutionalized because of severe hearing deficits. The fact that MMSE, ADL, and clarity of speech, all of which reflect aspects of cognitive function, all entered the multivariate analysis as significant contributors and all in the same direction, attests to the crucial role that cognitive function plays in regulating levels of engagement.

While it might be expected that the stimuli engendering the least engagement would be the most frequently refused, this was only true for real human contact. Analysis revealed that the inanimate social stimuli (ranked as 6 for engagement duration and 5 for attitude) was the most frequently rejected, and that simulated social stimuli ranked as 3rd for most engaging type of stimulus yet as 2nd for refusal. This discrepancy can be explained by the fact that participants with higher levels of cognitive function are the most engaged and also those most likely to refuse stimuli they deem least appropriate. However, for the more cognitively impaired portion of our sample, less “socially appropriate” stimuli such as stuffed animals, real-looking dolls, or robotic animals can be relatively soothing and engaging (especially in comparison to the lack of any stimulation - control activity).

The results have several implications of note. First, in terms of environmental preparation and adjustments, our findings imply that allowing residents to spend time with other persons will facilitate engagement. This group setting will likely assure the maintenance of some amount of background noise. The finding that a long presentation with modeling was preferable may be interpreted as reflecting the value of social interaction, suggesting that it is crucial to train, mentor, and monitor staff interaction with residents to assure that they know how to present stimuli in a positive and constructive manner. The consistent contribution of the long presentation with modeling to engagement in both uni- and multivariate analysis underscores its utility. The positive impact of one-on-one interaction on engagement is congruent with prior research (14), and indicates that nursing home staff should make a conscious effort to spend time with each resident, e.g., through a rotation schedule. If time constraints encroach on opportunities for one-on-one interaction, perhaps group activities could be conducted or alternative social stimuli offered, such as pet therapy and simulated interaction (15,32–34). The finding that exposure to any stimuli is preferable to nothing demonstrates that it would behoove nursing homes to have various stimuli available, particularly reasonable substitutions for social interaction when it is unavailable.

There are several limitations to the study. First, the methodology used was meant to clarify aspects of environment, personal, and stimulus attributes affecting engagement and was not conducted to maximize clinical utility. Future research will need to expand the concept and methodology to achieve greater clinical utility. Second, the utilization of the GEE methodology allowed us to include many different types of influences simultaneously, including those that changed in each presentation of the stimulus and those that remained constant (e.g., personal attributes). However, we were unable to include the even more complex issues of person–stimulus interaction. We have addressed those interactions in two papers, one relating to the personal meaning of a stimulus (35) and another to the relationship between past and present preferences and current levels of engagement (36). Future research should study potential environment-person interactions. We were able to document that the different factors enter the multivariate models as well, and thus have independent contribution to engagement. The contribution of this paper is therefore in showing that environment, person, and stimulus attributes affect engagement concurrently, which is consistent with the Comprehensive Process Model of Engagement. These findings should be expanded in future research where the Comprehensive Process Model of Engagement can be used in different populations or subpopulations and in different settings.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AG R01 AG021497. We thank the nursing home residents, their relatives, and the staff members and administration of the nursing homes for all of their help, without which this study would not have been possible. The corresponding author had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No disclosures to report.

References

- 1.Burgio LD, Scilley K, Hardin JM, et al. Studying disruptive vocalization and contextual factors in the nursing home using computer-assisted real-time observation. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1994;49(5):230–239. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.5.p230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Werner P. Observational data on time use and behavior problems in the nursing home. J Appl Gerontol. 1992;11(1):111–121. doi: 10.1177/073346489201100109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buettner L, Lundegren H, Lago D, et al. Therapeutic recreation as an intervention for nursing home residents with dementia and agitation: an efficacy study. Am J Alzheimers Dis. 1996;11(5):4–12. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engelman KK, Altus DE, Mathews RM. Increasing engagement in daily activities by older adults with dementia. J Appl Behav Anal. 1999;32(1):107–110. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen-Mansfield J, Dakheel-Ali M, Marx MS. Engagement in persons with dementia: The concept and its measurement. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(4):299–307. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31818f3a52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen-Mansfield J, Thein K, Dakheel-Ali M, et al. Engaging nursing home residents with dementia in activities: the effects of modeling, presentation order, time of day, and setting characteristics. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14(4):471–480. doi: 10.1080/13607860903586102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foster NA, Valentine ER. The effect of auditory stimulation on autobiographical recall in dementia. Exp Aging Res. 2001;27(3):215–218. doi: 10.1080/036107301300208664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Regier NG, et al. The impact of personal characteristics on engagement in nursing home residents. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(7):755–763. doi: 10.1002/gps.2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolanowski A, Buettner L, Litaker M, et al. Factors that relate to activity engagement in persons with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2006;21(1):15–22. doi: 10.1177/153331750602100109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dobbs D, Munn J, Zimmerman S, et al. Characteristics associated with lower activity involvement in long-term care residents with dementia. Gerontologist. 2005;45(1):81–86. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.suppl_1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Resnick HE, Fries BE, Verbrugge LM. Windows to their world: The effect of sensory impairments on social engagement and activity time in nursing home residents. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1997;52B(3):S135–S144. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.3.s135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Voelkl JE, Fries BE, Galecki AT. Predictors of nursing home residents’ participation in activity programs. Gerontologist. 1995;35(1):44–51. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chibnall JT, Tait RC, Harman B, et al. Effect of acetaminophen on behavior, well-being, and psychotropic medication use in nursing home residents with moderate-to-severe dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(11):1921–1929. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen-Mansfield J, Werner P. Management of verbally disruptive behaviors in the nursing home. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997;52A(6):M369–M377. doi: 10.1093/gerona/52a.6.m369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen-Mansfield J. Nonpharmacologic interventions for inappropriate behaviors in dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(4):361–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Camberg L, Woods P, Ooi WL, et al. Evaluation of simulated presence: A personalized approach to enhance well-being in persons with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(4):446–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb07237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garland K, Beer E, Eppingstall B, O’Connor DW. A comparison of two treatments of agitated behavior in nursing home residents with dementia: Simulated family presence and preferred music. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;15(6):514–521. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000249388.37080.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banks MR, Willoughby LM, Banks WA. Animal-assisted therapy and loneliness in nursing homes: Use of robotic versus living dogs. J Am Med Direc Assoc. 2008;9(3):173–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marx MS, Cohen-Mansfield J, Regier NG, et al. The impact of different dog-related stimuli on engagement of persons with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2010;25(1):37–45. doi: 10.1177/1533317508326976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gitlin LN, Winter N, Burke J, Chernett N, Dennis MP, Hauck WW. Tailored activities to manage neuropsychiatric behaviors in persons with dementia and reduce caregiver burden: a randomized pilot study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;16:229–239. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318160da72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen-Mansfield J, Kerin P, Pawlson LG, et al. Informed consent for research in the nursing home: Processes and results. Gerontologist. 1988;28(3):355–359. doi: 10.1093/geront/28.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall L, Hare J. Video respite™ for cognitively impaired persons in nursing homes. Am J Alzheimers Dis. 1997;12(3):117–121. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lund DA, Hill RD, Caserta MS, et al. Video respite™: An innovative resource for family, professional caregivers, and persons with dementia. Gerontologist. 1995;35(5):683–687. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.5.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen-Mansfield J, Werner P, Marx MS. An observational study of agitation in agitated nursing home residents. Int Psychogeriatr. 1989;1(2):153–165. doi: 10.1017/s1041610289000165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris J, Hawes C, Murphy K, et al. MDS Resident Assessment. Natick, MA: Eliot Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini Mental State. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen-Mansfield J, Parpura-Gill A, Golander H. Utilization of self-identity roles for designing interventions for persons with dementia. J Gerontol B: Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61B(4):202–212. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.4.p202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stoline MR. The status of multiple comparisons: simultaneous estimation of all pairwise comparisons in one-way ANOVA designs. Am Statistician. 1981;35:134–141. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Dakheel-Ali M, et al. Can persons with dementia be engaged with stimuli? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18:351–362. doi: 10.1097/jgp.0b013e3181c531fd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen-Mansfield J, Taylor J. Hearing aid in nursing homes part 1: Prevalence rates of hearing impairment and hearing aid use. J Am Med Direc Assoc. 2004;5(5):283–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Runci S, Doyle C, Redman J. An empirical test of language-relevant interventions for dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 1999;11(3):301–311. doi: 10.1017/s1041610299005864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Werner P, Cohen-Mansfield J, Fischer J, et al. Characterization of family-generated videotapes for the management of verbally disruptive behaviors. J Appl Gerontol. 2000;19(1):42–57. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zisselman MH, Rovner BW, Shmuely Y, et al. A pet therapy intervention with geriatric psychiatry inpatients. Am J Occupat Ther. 1996;50(1):47–51. doi: 10.5014/ajot.50.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohen-Mansfield J, Thein K, Dakheel-Ali M, et al. The underlying meaning of stimuli: Impact on engagement of persons with dementia. Psychiatry Res. 2010;177(1–2):216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Thein K, et al. The impact of past and present preferences on stimulus engagement in nursing home residents with dementia. Aging Mental Health. 2010;14(1):67–73. doi: 10.1080/13607860902845574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]