This is a report of an upper tract invasive urothelial carcinoma in a horseshoe kidney successfully managed with a combined hand-assisted laparoscopic nephroureterectomy and isthmusectomy with cystoscopic en-bloc excision of the distal ureter and bladder cuff.

Keywords: Urothelial carcinoma, Hand-assisted laparoscopic nephroureterectomy, Bladder cuff, Isthmusectomy, Laparoscopy

Abstract

Upper tract invasive urothelial carcinoma and horseshoe kidneys are familiar to the practicing urologist but relatively rare individual entities. The complication of managing them when they coexist in the same patient can be challenging. Herein, we present the first reported case in which an upper tract invasive urothelial carcinoma in a horseshoe kidney was successfully managed with a combined hand-assisted laparoscopic nephroureterectomy and isthmusectomy with cystoscopic en-bloc excision of the distal ureter and bladder cuff. This highlights the fact that complex anatomy can be managed in a completely minimally invasive fashion, and sound oncologic principles can still be maintained.

INTRODUCTION

A horseshoe kidney is seen in 0.25% of the population, and urothelial carcinoma (UC) of the upper urinary tract accounts for approximately 5% to 7% of all renal tumors.1 Nephroureterectomy is the gold standard for management of high-grade invasive UC.2 Laparoscopy has proven to be an effective technique for performing minimally invasive nephroureterectomy. Optimal management of the distal ureter has not been agreed upon, because many techniques have been described and are currently used. The presentation of these rare tumors and their management using a minimally invasive approach presents many potential challenges. Herein, we present the first reported case in which an upper tract invasive UC in a horseshoe kidney was successfully managed with a combined hand-assisted laparoscopic nephroureterectomy (HALNU) and isthmusectomy with cystoscopic en-bloc excision of the distal ureter and bladder cuff.

CASE REPORT

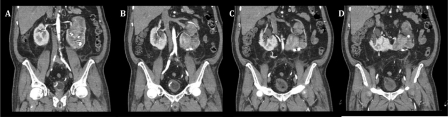

A 64-year-old white male presented with painless gross hematuria. He had a history of nephrolithiasis and a horseshoe kidney. Urine cytology was positive for high-grade UC. CT-angiography revealed a horseshoe kidney with 3 renal arteries to each moiety, nephrolithiasis bilaterally, and an enhancing hypovascular centrally located mass in the left moiety (Figure 1). Cystoscopy confirmed a normal lower urinary tract. Ureteroscopic biopsy of the left renal pelvic mass confirmed a high-grade papillary UC.

Figure 1.

ct abdomen/pelvis (a–d progresses from posterior to anterior) showing horseshoe kidney with multiple arteries, stones, and tumor in left renal moiety.

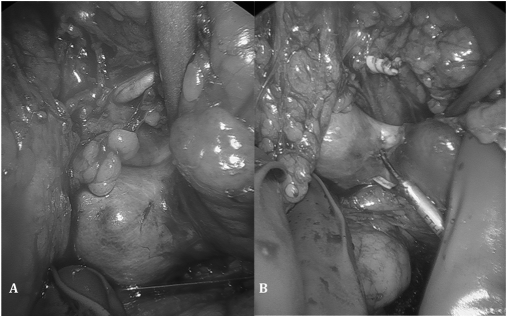

A left HALNU with cystoscopic en-bloc excision of the distal ureter and bladder cuff was performed.3 The isthmusectomy was performed after all ipsilateral renal arteries and renal vein had been secured and kidney mobilized. The isthmus was >3cm in width and depth, too large for our endoscopic GIA vascular stapler to control. We therefore scored the line of demarcation resulting from where the blood supply had been previously occluded in the isthmus with the hot blade of the ultrasonic scalpel (Figure 2). Isthmusectomy was completed with an ultrasonic hook. The remaining contralateral side of the isthmus was oversewn with a running 2-0 Vicryl suture to ensure hemostasis. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 3 after an unremarkable postoperative course.

Figure 2.

Before (a) and after (b) clipping of the arterial supply to the left kidney moiety. Note the perfusion line of demarcation in the isthmus.

Final pathology revealed an 11.5-cm high-grade papillary UC involving the renal pelvis and proximal ureter with focal renal parenchymal invasion. No tumor was present in 5 lymph nodes, and all surgical margins were negative (pT3N0Mx).

DISCUSSION

Invasive UC of the upper urinary tract can be managed laparoscopically without compromising oncologic outcomes.4 This holds true when the entire distal ureter and bladder cuff are excised, which can be done safely via cystoscopic excision.2

It has been documented that laparoscopy can be applied to horseshoe and renal fusion anomalies for a variety of pathologic processes, including performance of pyeloplasties for ureteropelvic junction obstruction,5 heminephrectomies for poor functioning kidney moieties,6 and radical7,8 and partial9 nephrectomies for renal cell carcinoma. To our knowledge, there are no reports of these techniques being applied to UC of the renal pelvis. Current literature highlights the complexities of operating on horseshoe kidneys laparoscopically, including identification and management of multiple renal arteries and performance of the isthmusectomy. We advocate preoperative imaging to identify the expected vascular anomalies. Intraoperatively, it is important to identify and skeletonize the major vessels to allow for full identification of all renal vessels. Equally important is to have appropriate equipment available to manage the isthmus, because it can be larger than expected and not amenable to the planned technique. Common to all approaches, it is important to secure all vascular structures prior to performing the isthmusectomy, as a line of perfusion will demarcate the isthmus that is supplied by the contralateral moiety vasculature. Staying on the unperfused side should allow a safe isthmusectomy by any technique.

CONCLUSION

Minimally invasive techniques for the management of large-volume invasive papillary UC can be safely and effectively applied to patients with horseshoe kidneys, thereby limiting morbidity while adhering to the principles of oncologic surgery.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Beverly K. Shipman for her assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

References:

- 1. Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Partin AW, Peters CA. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 9th ed Philadelphia: Saunders-Elsevier; 2007; 1638 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kurzer E, Leveillee R, Bird V. Combining hand assisted laparoscopic nephroureterectomy with cystoscopic circumferential excision of the distal ureter without primary closure of the bladder cuff: is it safe? J Urol. 2006; 175: 63–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wong C, Leveillee R. Hand-assisted laparoscopic nephroureterectomy with cystoscopic en bloc excision of the distal ureter and bladder cuff. J Endourol. 2002; 16: 329–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. El Fettouh HA, Rassweiler JJ, Schulze M, et al. Laparoscopic radical nephroureterectomy: results of an international multicenter study. Eur Urol. 2002; 42(5): 447–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bove P, Ong AM, Rha KH, Pinto P, Jarrett TW, Kavoussi LR. Laparoscopic management of ureteropelvic junction obstruction in patients with upper urinary tract anomalies. J Urol. 2004; 171(1): 77–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tan YH, Siddiqui K, Preminger GM, Albala DM. Hand-assisted laparoscopic nephrectomy for inflammatory renal conditions. J Endourol. 2004; 8: 770–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bhayani S, Andriole G. Pure laparoscopic radical heminephrectomy and partial isthmusectomy for renal cell carcinoma in a horseshoe kidney: case report and technical considerations. Urology. 2005; 66: 880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Araki M, Link BA, Galati V, Wong C. Hand-assisted laparoscopic radical heminephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma in a horseshoe kidney. J Endourol. 2007; 12: 1485–1487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Molina W, Gill I. Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy in a horseshoe kidney. J Endourol. 2003; 17: 905–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]