This review suggests that diagnostic laparoscopy during the third trimester of pregnancy is a logical strategy to minimize maternal and fetal risk when acute appendicitis is suspected.

Keywords: Appendicitis, Pregnancy, Laparoscopic procedure, Safety

Abstract

The presentation of acute appendicitis during pregnancy may cause diagnostic and therapeutic difficulty. Delay in diagnosis may lead to increased maternal and fetal risk. Therefore, an aggressive surgical approach is mandatory, even though this may result in an increased number of appendectomies for normal appendices. Diagnostic laparoscopy, followed by laparoscopic appendectomy in case of inflammation, seems a logical strategy. We present the case of a 36-week pregnant woman who presented with suspicion of acute appendicitis. The pro and cons of a laparoscopic approach in the third trimester of pregnancy are discussed as is its safety by reviewing the literature.

INTRODUCTION

Acute appendicitis during pregnancy is known to have an unspecific clinical presentation, particularly close to term, due to a change in physiological and anatomical constitution. Delay in diagnosis increases the risk of complications in mother and fetus, with maternal or fetal death being most feared.1,2,3 Therefore, an aggressive approach is recommended even though this leads to a higher rate of procedures for a noninflamed appendix. In 25% to 50% of patients, the preoperative diagnosis appears to be incorrect.4,5 Especially in pregnancy, a diagnostic laparoscopy followed by a laparoscopic appendectomy in case of inflammation seems a logical strategy to reduce unnecessary appendectomies. Especially in the third trimester of pregnancy when the fundus is located between the umbilicus and xiphoid, laparoscopy seems theoretically of additional (localizing) value.

Several studies6–12 have shown that diagnostic laparoscopy followed by laparoscopic appendectomy is feasible and safe during pregnancy. In a recent systematic review by Walch et al,13 however, the authors are prudent with the conclusion that a laparoscopic approach should be standard of care, as fetal loss appeared to be significantly higher with laparoscopic appendectomy (5% to 6%) compared to open appendectomy (1% to 3%, P=.001). By presenting the case of a 36-week pregnant woman with appendicitis, we would like to discuss the potential impact of this statement.

CASE REPORT

A 31-year-old woman was admitted to the obstetrical ward because of an unspecific pain in the abdomen in the 36th week of pregnancy. The onset of pain was 2 days prior to admission and had no specific location and had not migrated. The patient had not experienced any anorexia, nausea, or vomiting. Physical examination disclosed diffuse tenderness over the abdomen without defense or percussion pain. She had a slightly raised white blood cell count of 11.6 x 109/L and a serum C-reactive protein of 55k1U/L.

Additional abdominal ultrasonography revealed an undefined tubular structure in the right lower abdomen and was not conclusive about whether this was appendicitis. We decided to perform a diagnostic laparoscopy. An open introduction was chosen, 10cm below the xiphoid to minimize the chance of damage to the uterus and to have an optimal view of the remaining abdominal space. The additional trocars were placed under direct vision (Figure 1). The appendix was identified only after mobilization of the cecum, which was replaced cranially by the uterus, located just under the liver. By blunt dissection, the inflamed appendix could be released from the infiltrated subhepatic area behind the fundus uteri, and laparoscopic appendectomy was completed. The tubular structure in the right lower abdomen, seen on ultrasound, appeared during laparoscopy to be the ligamentum rotundum. Postoperative recovery was uncomplicated, and the patient was discharged 2 days after surgery. Preoperatively, right after surgery, and right before discharge, the fetal condition was checked by ultrasonography. In the 40th week of pregnancy, a healthy baby boy was born.

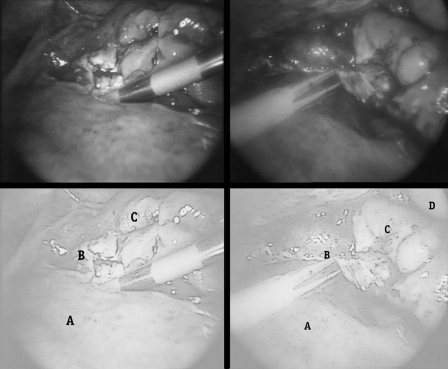

Figure 1.

Laparoscopic appendectomy and inflamed appendix dissected from behind the uterus. A: uterus; B: appendicular inflammation area (1), dissected appendix (2); C: transverse colon; D: Liver.

DISCUSSION

The accuracy of diagnostic tools for appendicitis during pregnancy is known to be low: abdominal ultrasonography is often inconclusive and CT scanning not prefered due to the radiation exposure.12,14,15 Recently, the role of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the diagnostic workup of pregnant women with abdominal complaints was studied.16,17 MRI has been proven to be safe during pregnancy and has a high sensitivity for appendicitis (97% to 100%) in patients with an inconclusive ultrasound. Disadvantages of the imaging technique are the high cost, limited availability, and learning curve in interpretation of the images. MRI has not yet been implemented as the standard workup for acute appendicitis in many hospitals.

Until now, an aggressive surgical strategy is mandated to minimize the risk of maternal morbidity and fetal loss associated with ruptured appendicitis, resulting from delayed diagnosis.5,18,19 Fetal loss associated with appendicitis is 2% to 3% in nonperforated appendicitis and increases up to 20% to 37% in patients with a perforated appendicitis.4–8 The mandatory aggressive surgical approach in these patients however is not without risk, because it leads to fetal loss or preterm delivery in 2% to 7% of patients, respectively, with an appendices sanae rate of 25% to 40%.4,5,20,21,22

As pregnancy progresses, localization of the appendix during open appendectomy may be troublesome, because the appendix is pushed upwards or laterally by the uterus. Furthermore, it is thought that manipulation and traction of the uterus, necessary to find or reach the appendix, increases the risk to premature postoperative delivery,20,23 ranging from 15% to 45%.4–8 This is a high toll, especially if a non-inflamed, healthy appendix is found.

In our case with a specific presentation and inconclusive ultrasonography, a direct incision at McBurney's point would have caused a lot of problems. The incision would have been too low to reach the appendix. The tubular structure seen on ultrasonography at this point appeared to be the ligamentum rotundum and not the location of the appendix. Although literature advises an incision at McBurney's point at any trimester of pregnancy, we would have been forced to prolong the incision cranially to be able to reach the appendix for inspection, creating a large wound. Because the appendix was located in an inflamed area subhepatically and behind the uterus, confirmation of an appendicitis and appendectomy would have been performed with manipulation and traction to the uterus. Laparoscopy offered us a minimally invasive approach to the region of interest.

Thus, laparoscopy has several diagnostic and navigational qualities. First, the appendix is easily localized, and additional incisions may be planned accordingly, reducing the risk of uterine irritability due to manipulation and traction. Second, in case of a normal appendix the procedure can be terminated. Third, with good visualization of other abdominal organs, the procedure offers an opportunity for a different diagnosis.

Laparoscopic appendectomy has the additional advantage of reduced postoperative pain compared to pain with open appendectomy, resulting in less fetal depression due to a reduction in pain medication, less maternal hypoventilation, and thromboembolic risk reduction, because of early mobilization and fewer wound complications.24–26

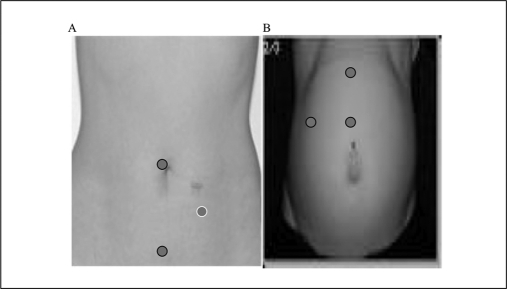

To perform a laparoscopy safely during pregnancy, guidelines have been formulated on introduction, pneumoperitoneal pressure, anesthesiological measures, and position of the pregnant patient. It is advised to start with an open (Hasson) introduction,6,28,29 to prevent the risk of Veress needle damage to intestine, aorta, or uterus. A case of fetal death due to pneumoamnion has been described.30 In a recent review, rates of entry-related complications were 2.8% in the Veress needle group and 0% in the Hasson open entry group. The introduction should be adjusted to the fundus height and placed cranially to the umbilicus or 3cm to 4cm above the highest level of the fundus uteri (Figure 2).6,27–29

Figure 2.

Trocar placement in nonpregnant (A) and pregnant women in the third trimester (B).

A capnogram is needed to measure the end-tidal CO2 to monitor the mother directly and the fetus indirectly. Pneumoperitoneum lowers the heart minute volume and raises systemic and pulmonary vascular resistance, leading to a rise in blood pressure. Maternal and fetal hypoxia can cause acidosis, which in turn can be corrected by hyperventilation. Ventilation guided by an anagram has been shown to prevent acidosis.31,32

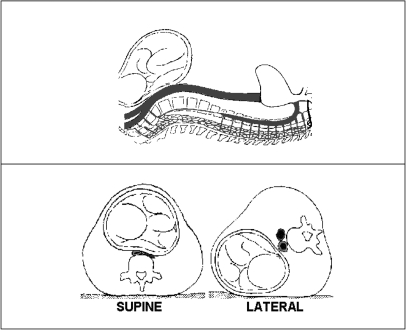

The pneumoperitoneal pressures are advised not to exceed 10mm Hg to12mm Hg as pneumoperitoneal pressures are attributable to fetal acidosis. In a recent study, pressures of 10mm Hg to 12mm Hg and an operation time of <1 hour did not show an adverse effect on fetal outcome. A left lateral tilt of the patient up to 15° to 30°, reducing compression of the vena cava and aorta, and reduced pneumoperitoneal pressures are both measures that minimize reduction of blood supply to the uterus and therefore avoid hypoxia of the fetus and risk of premature labor (Figure 3).33

Figure 3.

Left lateral tilt in pregnant women during laparoscopic procedures.

Two recent reviews13,34 on the laparoscopic approach during pregnancy contradict each other. Jackson et al34 have demonstrated good fetal and maternal outcome, supporting a laparoscopic procedure to be standard of care in any trimester. In this review, the largest series by McGory et al,35 with 454 cases of potential appendicitis, was not taken into account. The most recent systemic review13 in which the McGory study was included underlines the need to be more prudent with laparoscopy, because fetal loss is significantly higher (5% to 6%) compared to fetal loss with open appendectomy (1% to 3%, P=.001). For this statement, however, evidence is yet lacking, and for several reasons their conclusion may be criticized. First of all, the study by McGory et al is a retrospective observational study, and although a multivariable regression analysis was done, this does not correct for confounding by indication. Potential different prognostic groups are not identified, and therefore prospective randomization is the only sound research to determine whether one therapy is superior to the other.36 Secondly, the fetal loss rate in McGory's study compares favorably, especially for complicated appendicitis, to most literature reports on both the open and laparoscopic approach.4–8,23 Thirdly, their data could well be a plea against an open procedure, because they found significantly more preterm (<37 weeks) deliveries (81%) for the open appendectomy compared to the laparoscopic procedure (1% to 2%, P<.0001).

Based on a review of the literature, we believe that the fetal outcome is adversely affected by the type of infection during pregnancy and the misdiagnosed disease, rather than the laparoscopic procedure itself.

In the McGory et al study,35 complicated appendicitis remained a major positive predictor of fetal loss. Jackson et al34 showed an excellent fetal outcome for laparoscopic procedures in any disease other than complicated appendicitis.

We feel that our case of a suspicion of appendicitis in the third trimester underlines the important role of a laparoscopic procedure. The navigational and diagnostic aspects of a laparoscopic procedure could well be too important to be advised against. Sound knowledge of the pros and cons are vital, and the guidelines for a safe procedure should be respected.

It is not unlikely that the gain for fetal outcome in the future lies in the diagnostic pathway rather than the type of surgery. Implementation of MRI might reduce the rate of negative appendectomies as well as the rate of complicated appendicitis, both improving fetal outcome significantly.

References:

- 1. Sauerland S, Lefering R, Neugebauer EAM. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for suspected appendicitis [Cochrane review]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(2): CD001546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pastore PA, Loomis DM, Sauret J. Appendicitis in pregnancy. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006; 19: 621–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown JJ, Wilson C, Coleman S, Joypaul BV. Appendicitis in pregnancy: an ongoing diagnostic dilemma. Colorectal Dis. 2009; 11(2): 116–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Levine D. Obstetric MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006; 24: 1–15 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tracey M, Fletcher HS. Appendicitis in pregnancy. Am Surg. 2000; 66: 555–559 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reedy MB, Kallen B, Kuehl TJ. Laparoscopy during pregnancy: a study of five fetal outcome parameters with use of the Swedish Health Registry. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997; 177(3): 673–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cohen-Kerem R, Railton C, Oren D, Lishner M, Koren G. Pregnancy outcome following non-obstetric surgical intervention. Am J Surg. 2005; 190(3): 467–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oelsner G, Stockheim D, Soriano D, Goldenberg M, Seidman DS, Cohen SB. Pregnancy outcome after laparoscopy or laparotomy in pregnancy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003; 10(2): 200–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Glasgow RE, Visser BC, Harris HW, Patti MG, Kilpatrick SJ, Mulvihill SJ. Changing management of gallstone disease during pregnancy. Surg Endosc. 1998; 12(3): 241–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Affleck DG, Handrahan DL, Egger MJ, Price RR. The laparoscopic management of appendicitis and cholelithiasis during pregnancy. Am J Surg. 1999; 178(6): 523–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barone JE, Bears S, Chen S, Tsai J, Russell JC. Outcome study of cholecystectomy during pregnancy. Am J Surg. 1999; 177(3): 232–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rollins MD, Chan KJ, Price RR. Laparoscopy for appendicitis and cholelithiasis during pregnancy: a new standard of care. Surg Endosc. 2004; 18(2): 237–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Walch CA, Tang T, Walch SR. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in pregnancy: a systematic review. Int J Surg. 2008; 6(4): 339–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lim HK, Bae SH, Seo GS. Diagnosis of acute appendicitis in pregnant women: value of sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992; 159: 539–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Hauth JC, Gilstrap LC, III, Wenstrom KD. Williams Obstetrics. 22nd ed New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Singh A, Danrad R, Hahn PF, Blake MA, Mueller PR, Novelline RA. MR imaging of the acute abdomen and pelvis: acute appendicitis and beyond. Radiographics. 2007; 27: 1419–1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Greenhalgh R, Punwani S, Taylor SA. Is MRI routinely indicated in pregnant patients with suspected appendicitis after equivocal ultrasound examination. Abdom Imaging. 2008; 33: 21–25 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eryilmaz R, Sahin M, Bas G, Alimoglu O, Kaya B. Acute appendicitis during pregnancy. Dig Surg. 2002; 19: 40–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bisharah M, Tulandi T. Laparoscopic surgery in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 46: 92–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Soriano D, Yefet Y, Seidman DS, Goldenberg M, Mashiach S, Oelsner G. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy in the management of adnexal masses during pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 1999; 71(5): 955–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lemaire BM, van Erp WF. Laparoscopic surgery during pregnancy. Surg Endosc. 1997. January; 11(1): 15–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gurbuz AT, Peetz ME. The acute abdomen in the pregnant patient Is there a role for laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 1997; 11(2): 98–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Curet MJ. Special problems in laparoscopic surgery. Previous abdominal surgery, obesity, and pregnancy. Surg Clin North Am. 2000; 80(4): 1093–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pucci RO, Seed RW. Case report of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the third trimester of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991; 165(2): 401–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Weber AM, Bloom GP, Allan TR, Curry SL. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1991; 78: 958–959 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Williams JK, Rosemurgy AS, Albrink MH, Parsons MT, Stock S. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in pregnancy. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1995; 40(3): 243–245 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Society of American Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) Guidelines for laparoscopic surgery during pregnancy. Surg Endosc. 1998; 12: 189–190 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moreno-Sanz C, Pascual-Pedreño A, Picazo-Yeste JS, Seoane-Gonzalez JB. Laparoscopic appendectomy during pregnancy: between personal experiences and scientific evidence. J Am Coll Surg. 2007; 205: 37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barnes SL, Shane MD, Schoemann MB, Bernard AC, Boulanger BR. Laparoscopic appendectomy after 30 weeks pregnancy: report of two cases and description of technique. Am Surg. 2004; 70: 733–736 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Friedman JD, Ramsey PS, Ramin KD, Berry C. Pneumoamnion and pregnancy loss after second trimester laparoscopic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2002; 99: 512–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bhavani-Shankar K, Steinbrook RA, Brooks DC, Datta S. Arterial end-tidal carbon dioxide pressure difference during laparoscopic surgery in pregnancy. Anesthesiology. 2000; 93: 370–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reedy MB, Galan HL, Bean-Lijewski JD, Carnes A, Knight AB, Kuehl TJ. Maternal and fetal effects of laparoscopic insufflation in gravid baboon. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1995; 2: 399–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Curet MJ, Vogt DA, Schob O, Qualls C, Izquierdo LA, Zucker KA. Effects of CO2 pneumoperitoneum in pregnant ewes. J Surg Res. 1996; 63: 339–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jackson H, Granger S, Price R, et al. Diagnosis and laparoscopic treatment of surgical diseases during pregnancy: an evidence-based review. Surg Endosc. 2008; 22(9): 1917–1927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McGory ML, Zingmond DS, Tillou A, Hiatt JR, Ko CY, Cryer HM. Negative appendectmomy in pregnant women is associated with a substantial risk of fetal loss. J Am Coll Surg. 2007; 205(4): 534–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. VandenBroucke JP. When are observational studies as credible as randomised trials. Lancet. 2004; 363: 1728–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]