Abstract

Pediatric antiretroviral adherence is difficult to assess, and subjective measures are affected by reporting bias, which in turn may depend on psychosocial factors such as alcohol use and depression. We enrolled 56 child–caregiver dyads from Cape Town, South Africa and followed their adherence over 1 month via various methods. The Alcohol Use Disorder Inventory Tool and Beck Depression Inventory 1 were used to assess these factors and their affect on pediatric adherence. The median age of the children was 4 years, and median time on antiretrovirals was 20 months. Increased time on ART was associated with poorer adherence via 3-day recall (3DR; p=0.03). Ethanol use was inversely associated with adherence by both subjective measures, 3DR and visual analogue scale (VAS) (both p<0.01), and with Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS) adherence as a continuous variable. In a multivariate analysis predicting MEMS adherence greater than 95%, including variables that were associated with adherence in univariate analyses, having a mother as a caregiver and shorter time on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) were significantly associated with adherence (odds ratio [OR] 19.2; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1–327 and 0.9; 95% CI 0.9–0.99). Pediatric adherence is affected by caregiver alcohol use, but caregiver relationship to the child is most important. This small study suggests that interventions should aim to keep mothers healthy and alive, as well as alcohol-free.

Introduction

Adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) is challenging, particularly in pediatrics, where liquid formulations make medication measurements difficult, palatability is an issue, and adherence depends on a caregiver to dispense doses. This is further complicated by the fact that HIV is most often transmitted from mother to child, therefore the infected child often has a caregiver who is also HIV-infected, or a nonbiological parent. Approximately one third of HIV-infected persons are depressed.1 Depression has been shown to be associated with poor adherence in adults and adolescents in the developed world.2–5 The same is true in African settings.6,7 In a meta-analysis of the effects of depression and anxiety on adherence, depressed patients had three times the odds of noncompliance compared to nondepressed patients.8 Caregiver psychosocial stress has also been associated with poorer pediatric adherence.9 Few studies have examined the effects of caregiver depression on pediatric adherence, and to our knowledge, none has examined the effects of caregiver depression or psychosocial stress on pediatric adherence in Africa.

In adult cohorts in resource-rich settings, poor adherence to ART has been associated with alcohol use, particularly in women.10,11 Studies suggest that the same may be true in resource-limited settings.12 In a U.S. study, caregiver drug and alcohol use was associated with poorer adherence, as well as higher viral loads in the children.13 However, few studies have examined alcohol affects on pediatric adherence in sub-Saharan Africa.

The effect of orphan status on pediatric ART adherence has been investigated in a number of settings with conflicting outcomes.14–18 These studies differ in their definition of orphanhood,2,9,12,14,19,20 and in the comparison group (i.e., children with biological parents versus foster parents,20 institution staff,21 or extended family. The cohorts studied have also been from varied cultures, including East Africa, Malawi, India, Thailand, and Brazil. However, to our knowledge, none has taken place in South Africa.

Most studies assessing the affect of psychosocial factors on adherence in children use self-report as measures of adherence, which is likely to be affected by the very factors they are measuring. Some use pill counts or pharmacy refills as their measures and these are not as accurate for measuring adherence as they are in adults,22 likely because dispensing of exact volumes of liquid medicine is not possible.

We recently compared multiple subjective and objective measures of adherence in South African children on ART, and found that none was as accurate as electronic measurements such as Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS).22 In the present study, we aimed to assess the effect of alcohol use and depression in the caregivers of this cohort of children on adherence measured by multiple tools.

Methods

Setting

The study took place in Gugulethu in the Nyanga district of Cape Town, with a 29% antenatal HIV seroprevalence in 2005. The Hannan Crusaid Treatment Centre (HCTC) has been delivering ART to this community since 2002.23 By February 2008, 312 children had been treated with ART at this site. Most children are commenced on non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based regimens (NNRTI), usually stavudine (d4T), lamivudine (3TC), and efavirenz (EFV) or nevirapine (NVP). A lopinavir/ritonavir–based therapy (LPV/r) is offered for those who had NNRTI-based prevention of mother-to-child-transmission therapy (PMTCT) or for whom first-line treatment fails. Routine follow-up is monthly to month 4 and then every 4 months. Viral load and CD4 counts are completed every 4 months.

There is strong client-centered adherence support at this clinic. Prior to treatment initiation, caregivers attend three group “treatment readiness” sessions. Trained adherence counselors perform home visits at set intervals for adherence support, with frequency decreasing over time in patients doing well on therapy. There is, similarly, an intensification of visits and support in those patients whose viral loads or pill counts suggest less than adequate adherence.

Design

We conducted a cross-sectional study in all children and their caregivers who attended the clinic during July and August of 2007 and who were taking at least one liquid medication. Caregivers and children were enrolled after informed consent was obtained. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Cape Town approved the study.

Measurements

Clinical histories were collected from the children's medical records. These included age, ART regimen and date of initiation, World Health Organization (WHO) stage at treatment initiation, any changes to ART regimen, and most recent CD4% and viral load (VL). Caregivers completed a basic demographic and ART questionnaire at the enrollment visit. We used five measures of children's ART adherence: medication event monitoring system (MEMS): visual analogue scales (VAS); 3-day recall of missed doses (3DR); pharmacy refill data (PR); and measurement of returned syrups (RS). These are described in detail elsewhere.22

Each participant was equipped with a MEMS cap (Aardex Corp., Zug, Switzerland) for a 1-month period. The MEMS cap was fitted on one of the three liquid antiretroviral (ARV) agents, most frequently 3TC or AZT. At the follow-up visit caregivers completed a questionnaire about their MEMS handling habits. Data from the cap were downloaded using PowerView 3.3 (Aardex Corp., Zug, Switzerland). Adherence descriptions created were (a) the percentage of doses taken during the 4-week monitoring interval (overall MEMS) and (b) the percentage of doses taken at the prescribed 12-h intervals (with a 2-h window allowed; timed MEMS). Data from the MEMS caps were analyzed to obtain mean individual adherence rates over time. At the follow-up visit, all caregivers were asked to rate their adherence on a VAS, ranging from 0% to 100%. Caregivers were also asked about their medication-administering behavior over the past 3 days via an adapted and translated version of the recall questionnaire developed by the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group (3DR). At this visit, adherence counselors also measured the amount of RS using a measuring cylinder. For all participants, data on previously dispensed medication was collected for the 4 months preceding enrollment using the clinic pharmacy's intelligent dispensing of ART software system (iDart) and medical records. We recorded both the number of times that medication was dispensed and the interval between dispensing visits (PR).

The alcohol and depression questions were also asked at the follow-up visit. Caregivers completed questionnaires that included The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), an 8-question tool. A score of 8 or more is indicative of problem drinking. The questionnaire also included the Beck Depression Inventory 1 (BDI1), which has 21 questions, scoring a total of 3 points each. A score of less than 10 being no depression, 10–18, mild-moderate depression; 19–29, moderate-severe depression, and 30–63 being severe depression. The caregiver was interviewed by a research-trained nurse in their preferred language. The nurse did not belong to the regular clinic staff, in order to minimize the risk of obtaining answers influenced by social desirability or fear of negative treatment repercussions. Additionally, both the BDI and the AUDIT were translated into Xhosa and have been validated in South African populations.24,25

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze children's and caregivers' characteristics and variables related to treatment outcome. Normally distributed continuous variables were described using means and standard deviations (SD); non-normally distributed ones using medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). Discrete data were described using counts and percentages. To express adherence as a binary variable, the defined cut-off value was at 95% of the continuous data for all measures, except for MEMS when considering the correct timing of doses. Patients above this cut-off were defined as adherent, patients below as non-adherent. For alcohol and depression tools, scores were calculated, and associations with adherence and other factors were examined using Fisher's exact, χ2, analysis of variance (ANOVA), where appropriate, and logistic regression when adjusting for other variables. Depression and alcohol use were also assessed by creating binary variables: depressed (mild, moderate or severe) versus not depressed; any versus no alcohol use. Alcohol use and depression were also evaluated as a continuous variables equal to the AUDIT score and BDI score, respectively. The level of significance for all analyses was p<0.05. Adjustments for multiple comparisons were made using the False discovery rate step-down procedure.26 In a multivariate analysis, all factors associated with adherence by any measure with unadjusted p close to or=0.05 were included, as were obvious confounders (e.g., caregiver as mother and caregiver on highly active antiretroviral therapy [HAART]). All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 9.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Of the 56 child–caregiver dyads that were enrolled, 54 had complete data for analysis. The median age of children was 4 years (IQR, 3–6.5) and 53% were female (n=28). They had been on ART for a median time of 20 months (IQR 15–32 months). Most children had started ART with WHO stage 3 or 4 (n=37, 71%), and were receiving first-line ART (n=50, 94%). Detailed demographics, adherence results, and analyses are reported elsewhere.22

Median age of caregiver was 31 years, 17 (33%) caregivers were on HAART themselves (Table 1). Mothers were most commonly the primary caregiver for these children (75%, n=41), then grandmothers (15%, n=8). Only 1 caregiver scored in the alcohol abuse category (score ≥8) on the AUDIT. A high proportion (33%, n=18) of the caregivers scored in the depressed range on the BDI.

Table 1.

Demographics, Alcohol Use, and Depression Scores of the Caregivers

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Caregiver | 53 | |

| Mother | 41 | 76 |

| Grandmother | 8 | 15 |

| Father | 2 | 4 |

| Aunt | 2 | 4 |

| Older sibling | 1 | 2 |

| Caregiver on HAART | 17 | 33 |

| Any alcohol use | 9 | 17 |

| Audit score <8 | 8 | 16 |

| Audit score 8 | 1 | 2 |

| Depression | 18 | 35 |

| None | 33 | 65 |

| Mild to moderate | 13 | 25 |

| Moderate to severe | 4 | 8 |

| Severe | 1 | 2 |

HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy.

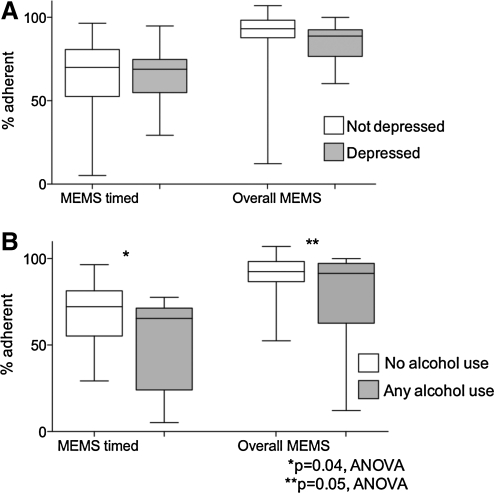

The relationship between adherence measured via various tools and various psychosocial indicators was assessed in univariate analyses (Table 2). Child age and gender was not associated with adherence by any measure. Time on ART was associated with adherence via 3DR (p=0.03 after adjustment). Having a mother as a caregiver improved adherence via MEMS measures, 3DR, and pharmacy refills, but these associations were not significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons. Mothers were not significantly more or less likely to be depressed than other caregivers (data not shown). Ethanol use was associated with poorer adherence by both of the subjective measures, 3DR and VAS (p<0.01 for both after adjustment for multiple comparisons). Adherence as measured by correct timing of doses on MEMS (±1 h; MEMS timed) and overall MEMS adherence was not related to depression (Fig. 1A). However, both of these measurements were associated with any alcohol use (Fig. 1B).

Table 2.

Psychosocial Indicators as Predictors of Adherence Measured by Various Methods

| |

MEMS timed |

MEMS |

3DR |

VAS |

Pharmacy refills |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <90% n=42 | >90% n=12 | <95% n=28 | >95% n=24 | <100% n=4 | 100% n=50 | <100% n=5 | 100% n=49 | ≤80% n=44 | >80% n=10 | |

| Mean age of child (yrs) | 4.37 | 4.91 | 4.21 | 4.79 | ρ=−0.04a | 3.8 | 4.6 | 4.5 | 4.6 | |

| Male gender, n (%) | 20 (48) | 5 (45) | 15 (52) | 13 (54) | 24 (96) | 25 (90) | 2 (40) | 23 (48) | 18 (42) | 7 (70) |

| Median months on ART | 24 | 19 | 20 | 24 | ρ=−0.48a | 44 | 20 | 20 | 29.5 | |

| Stage 3 or 4, n (%) | 39 (95) | 8 (73) | 21 (75) | 16 (67) | 4 (100) | 33 (69) | 5 (100) | 32 (68) | 39 (93) | 8 (80) |

| Median CG age (yrs) | 30 | 31 | 30 | 31 | ρ=0.24a | 28 | 31 | 31 | 29.5 | |

| CG on HAART, n (%) | 11 (26) | 6 (50) | 6 (21) | 11 (44) | 1 (25) | 16 (32) | 1 (20) | 16 (33) | 13 (30) | 4 (40) |

| CG mother, n (%) | 29 (69) | 12 (100) | 18 (62) | 23 (92) | 2 (50) | 39 (78) | 4 (80) | 37 (76) | 31 (70) | 10 (100) |

| CG depressed, n (%) | 13 (31) | 8 (67) | 11 (38) | 10 (40) | 1 (25) | 20 (40) | 2 (40) | 19 (39) | 20 (45) | 1 (10) |

| Mean AUDIT score | 0.9 | 0 | 1.1 | 1.0 | ρ=−0.44a | 3 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.7 | |

| NNRTI regimen, n (%) | 7 (58) | 5 (19) | 13 (46) | 12 (46) | 2 (50) | 24 (48) | 2 (40) | 24 (49) | 23 (52) | 3 (30) |

Pearsons correlations with continuous variables calculated.

Shaded cells are those with p≤0.05 after adjustment for multiple comparisons via the False Discover Rate step-down procedure.26

MEMS timed 90, 90% of doses were taken=/ −1 h from prescribed 12-hourly dose; MEMS 95, 95% of doses were taken for the month; 3DR, 3 day recall; VAS, visual analogue scale; CG, caregiver; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; MEMS, Medication Event Monitoring System.

FIG. 1.

Adherence as a proportion of correct doses (overall MEMS) and of correctly timed doses (MEMS timed) and their relationship to (A) depression and (B) alcohol use.

In a multivariate analysis predicting MEMS adherence greater than 95%, including variables that were associated with adherence in unadjusted univariate analyses (Table 3), i.e., caregiver relationship to the child (mother versus other), depression as a binary variable (depressed versus not), alcohol use (as a continuous AUDIT score), the period of time the child had been receiving ART in months, and whether the caregiver was on HAART (as a potential confounder for caregiver relationship), only having a mother as a caregiver and shorter time on HAART were significantly associated with adherence (OR 29.1; 95% CI 1.3–628 and 0.9–0.99; Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate Analysis Predicting MEMS Adherence ≥95%

| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Caregiver on HAART | 4.9 | 0.9–26 |

| Caregiver mother | 19.2 | 1.1–327 |

| Caregiver depression | 0.8 | 0.2–3.7 |

| Months on HAART | 0.9 | 0.9–0.99 |

| AUDIT score | 0.7 | 0.4–1.2 |

| Caregiver age | 1.0 | 0.9–1.1 |

MEMS, Medication Event Monitoring System; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Discussion

In our cohort, we measured adherence via five methods and administered BDI and AUDIT questionnaires to measure depression and alcohol use. Depression as measured by BDI was common in this setting (35%). High rates of depression in HIV-infected adults in this setting have been reported previously,25,27,28 far higher than that in general South African population.29 It is possible that this high prevalence was due to the cross-cultural use of the BDI1, however this tool has previously been validated in South Africa, and studies utilizing other tools have had similar findings.25,27–33 In contrast, reported problem drinking as measured by AUDIT was rare.

The limitations of these data are the small sample size, therefore, poorly representative of the general population. The small sample size may also contribute to the large confidence intervals around the significant factors in our multivariate model. Also, we used subjective tools used to measure alcohol use and depression, although validated for their use in this setting. Additionally, due to the short observation period, it is possible that self-reported behavior was modified due to the Hawthorne effect. The limitations of the adherence measures themselves are discussed in detail elsewhere.22

Since alcohol abuse as measured via AUDIT was rare, it was not associated with adherence when analyzed with the recommended cutoff score of 8. When comparing AUDIT score as a continuous variable and adherence, alcohol use was strongly negatively associated with subjective measures of adherence. When analyzing adherence via either MEMS measure, correct timing of doses, and correct number of doses as continuous variables, AUDIT score was correlated but depression was not (Fig 1). Chander et al.34 found in a cohort of adults on ART, hazardous alcohol use was independently associated with decreased ART utilization, adherence, and viral suppression compared to no alcohol use. In this cohort, they classified hazardous ethanol use as more than 7 or 14 drinks per week or 3 or 4 drinks per occasion in women and men respectively. Therefore, the AUDIT scale may underestimate the amount of alcohol use that affects adherence.

We found that in a multivariate analysis, longer time on ART was associated with poorer adherence as measured by MEMS. A trend toward poorer adherence has been associated with increasing time on therapy among adults.35 In a Ugandan study, there was a significant decline in adherence over time on therapy among family members.7 This highlights the importance of ongoing adherence support as apposed to interventions that focus on ART initiation only.

Having a mother as a caregiver was associated with improved adherence by multiple unadjusted subjective and objective measures, and was associated with adherence by MEMS even after adjusting for caregiver age and whether the caregiver themselves was on ART. In a large cohort of children and adolescents in the United States, with a median age of 11 years, having a biological parent as the primary caregiver was negatively associated with adherence.2 Studies from underdeveloped settings have also found that foster parents were better at administering medication than biological parents.20 However, other studies found orphan status to have no relationship to reported adherence.21,36. These cohorts differ in their definition of orphan status; some consider children without either a mother or a father as an orphan,17 whereas others define orphans as having either both parents or mother deceased.1. Also, adherence in these studies was often measured via self-report or pill count,14,15,20 and our prior data shows that these are not reliable.22 In our cohort, using MEMS as the adherence measure, a mother as caregiver versus any other relative was associated with improved adherence. We did not specifically ask if the “mother” was biological. It is possible, as is sometimes the case in Xhosa culture, that primary caregivers other than the biological mother were referred to as the “mother.” We also did not ask whether the biological parents were deceased when a non-biological parent was the caregiver. It is a common in this culture that fathers are absent from caring for children although they are alive, and therefore children may be cared for by others although they are not true orphans. Although adjusting for months on HAART and age of child did not decrease the association between adherence and caregiver relationship to child, it is clear from multiple other studies that orphans in African settings have delayed access to care.15–17 Therefore, ART programs should strive to keep mother figures healthy enough to care for their children, or to keep children in tight family units where a “mother” figure is administering therapy. Maternal health, particularly mental health, is often neglected when caring for children with HIV, and our study highlights the importance of a family approach to care.

Acknowledgments

Heather Jaspan is supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Training Grant 5T32HD007233-28. MEMS caps and equipment were donated by Aardex Corp. (Zug, Switzerland).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Bing EG. Burnam MA. Longshore D, et al. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:721–728. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams PL. Storm D. Montepiedra G, et al. Predictors of adherence to antiretroviral medications in children and adolescents with HIV infection. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1745–1757. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner BJ. Laine C. Cosler L. Hauck WW. Relationship of gender, depression, and health care delivery with antiretroviral adherence in HIV-infected drug users. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:248–257. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20122.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villes V. Spire B. Lewden C, et al. The effect of depressive symptoms at ART initiation on HIV clinical progression and mortality: Implications in clinical practice. Antivir Ther. 2007;12:1067–1074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vranceanu AM. Safren SA. Lu M, et al. The relationship of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression to antiretroviral medication adherence in persons with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2008;22:313–321. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amberbir A. Woldemichael K. Getachew S. Girma B. Deribe K. Predictors of adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected persons: A prospective study in Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:265. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byakika-Tusiime J. Crane J. Oyugi JH, et al. Longitudinal antiretroviral adherence in HIV+ Ugandan parents and their children initiating HAART in the MTCT-Plus family treatment model: Role of depression in declining adherence over time. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(Suppl 1):82–91. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9546-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiMatteo MR. Lepper HS. Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: Meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marhefka SL. Tepper VJ. Brown JL. Farley JJ. Caregiver psychosocial characteristics and children's adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2006;20:429–437. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lazo M. Gange SJ. Wilson TE, et al. Patterns and predictors of changes in adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy: Longitudinal study of men and women. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:1377–1385. doi: 10.1086/522762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Applebaum AJ. Richardson MA. Brady SM. Brief DJ. Keane TM. Gender and other psychosocial factors as predictors of adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in adults with comorbid HIV/AIDS, psychiatric and substance-related disorder. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:60–65. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9441-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silva MC. Ximenes RA. Miranda Filho DB, et al. Risk-factors for non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2009;51:135–139. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652009000300003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naar-King S. Arfken C. Frey M. Harris M. Secord E. Ellis D. Psychosocial factors and treatment adherence in paediatric HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2006;18:621–628. doi: 10.1080/09540120500471895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vreeman RC. Wiehe SE. Ayaya SO. Musick BS. Nyandiko WM. Association of antiretroviral and clinic adherence with orphan status among HIV-infected children in Western Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49:163–170. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318183a996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nyandiko WM. Ayaya S. Nabakwe E, et al. Outcomes of HIV-infected orphaned and non-orphaned children on antiretroviral therapy in western Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:418–425. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243122.52282.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ntanda H. Olupot-Olupot P. Mugyenyi P, et al. Orphanhood predicts delayed access to care in Ugandan children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:153–155. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318184eeeb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiboneka A. Wangisi J. Nabiryo C, et al. Clinical and immunological outcomes of a national paediatric cohort receiving combination antiretroviral therapy in Uganda. AIDS. 2008;22:2493–2499. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328318f148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhattacharya M. Rajeshwari K. Saxena R. Demographic and clinical features of orphans and nonorphans at a pediatric HIV centre in North India. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:627–631. doi: 10.1007/s12098-010-0076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polisset J. Ametonou F. Arrive E. Aho A. Perez F. Correlates of adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected children in Lome, Togo, West Africa. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:23–32. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9437-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giannattasio A. Barbarino A. Lo Vecchio A. Bruzzese E. Mango C. Guarino A. Effects of antiretroviral drug recall on perception of therapy benefits and on adherence to antiretroviral treatment in HIV-infected children. Curr HIV Res. 2009;7:468–472. doi: 10.2174/157016209789346264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wachholz NI. Ferreira J. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in children: A study of prevalence and associated factors. Cad Saude Publica. 2007;23(Suppl 3):S424–434. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2007001500010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muller A. Jaspan H. Myer L. Lewis A. Harling G. Bekker LG. Orrell C. Standard measures are inadequate to monitor adherence in a resource-limited pediatric setting. AIDS Behav. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9825-6. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawn SD. Little F. Bekker LG, et al. Changing mortality risk associated with CD4 cell response to antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. AIDS. 2009;23:335–342. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328321823f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schoeman JH. Parry CD. Lombard CJ. Klopper HJ. Assessment of alcohol-screening instruments in tuberculosis patients. Tuber Lung Dis. 1994;75:371–376. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(94)90084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kagee A. Martin L. Symptoms of depression and anxiety among a sample of South African patients living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2010;22:159–165. doi: 10.1080/09540120903111445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Columb M SS. Multiple Comparisons. Curr Anesth Crit Care. 2006;17:233–236. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myer L. Stein DJ. Grimsrud AT, et al. DSM-IV-defined common mental disorders: Association with HIV testing, HIV-related fears, perceived risk and preventive behaviours among South African adults. S Afr Med J. 2009;99(5 Pt 2):396–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myer L. Seedat S. Stein DJ. Moomal H. Williams DR. The mental health impact of AIDS-related mortality in South Africa: A national study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:293–298. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.080861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomlinson M. Grimsrud AT. Stein DJ. Williams DR. Myer L. The epidemiology of major depression in South Africa: Results from the South African stress and health study. S Afr Med J. 2009;99(5 Pt 2):367–373. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spies G. Kader K. Kidd M, et al. Validity of the K-10 in detecting DSM-IV-defined depression and anxiety disorders among HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Care. 2009;21:1163–1168. doi: 10.1080/09540120902729965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh D. Sunpath H. John S. Eastham L. Gouden R. The utility of a rapid screening tool for depression and HIV dementia amongst patients with low CD4 counts—A preliminary report. Afr J Psychiatry (Johannesbg) 2008;11:282–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Myer L. Smit J. Roux LL. Parker S. Stein DJ. Seedat S. Common mental disorders among HIV-infected individuals in South Africa: Prevalence, predictors, and validation of brief psychiatric rating scales. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2008;22:147–158. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamad R. Fernald LC. Karlan DS. Zinman J. Social and economic correlates of depressive symptoms and perceived stress in South African adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:538–544. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.066191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chander G. Lau B. Moore RD. Hazardous alcohol use: A risk factor for non-adherence and lack of suppression in HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:411–417. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243121.44659.a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maggiolo F. Ripamonti D. Arici C, et al. Simpler regimens may enhance adherence to antiretrovirals in HIV-infected patients. HIV Clin Trials. 2002;3:371–378. doi: 10.1310/98b3-pwg8-pmyw-w5bp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biadgilign S. Deribew A. Amberbir A. Deribe K. Barriers and facilitators to antiretroviral medication adherence among HIV-infected paediatric patients in Ethiopia: A qualitative study. SAHARA J. 2009;6:148–154. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2009.9724943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]