Abstract

Background:

This study was carried out to investigate the effectiveness of a propolis-containing mouthrinse in inhibition of plaque formation and improvement of gingival health.

Materials and Methods:

Thirty subjects were selected and randomly assigned into three groups of ten subjects each, which received a propolis-containing mouthrinse, or a negative control (Saline) or a positive control (Chlorhexidine 0.2%). Plaque index and gingival index were assessed at baseline and at a five-day interval.

Results:

Chlorhexidine mouthwash was found to be better than propolis and saline in inhibiting plaque formation. Propolis was found to be only marginally better than chlorhexidine in improving gingival scores.

Conclusion:

The present study suggests that propolis might be used as a natural mouthwash, an alternative to chemical mouthwashes, e.g., chlorhexidine. Further, long term trials are required for more accurate data and any conclusive evidence.

Keywords: Gingivitis, periodontitis, mouthwashes

INTRODUCTION

Bees and dentists have a few things in common- They are both hardworking, industrious and have a capacity to cause a great deal of discomfort and pain!! However, the power and ability to heal is also something we dentists have in common with our little winged friends too!!! Propolis, is derived from the Greek pro – ‘for or in defence of’ and polis – ‘the city’, hence, ‘defender of the city/hive’. Propolis is a naturally-occurring bee product. It is a hard resinous substance consisting chiefly of wax and plant extracts. It plays a role in the bee colony as protection against invasion and infection, providing the bees with an ‘immune system’ and is used to seal the hive.

Propolis was first used as a medicine by the Egyptians and use of it was continued by the Greeks and Romans. The major constituents of propolis are flavones, flavanones, and flavanols. It is used in homeopathic and herbal practice as an antiseptic, anti-inflammatory, antimycotic, and bacteriostatic agent.

There are many clinical applications of propolis in dentistry. To exemplify, a few are- relief from denture ulcerations and stomatitis, halitosis, mouth freshener, periodontal pocket / abscess, mouthwash, cervical, dentinal, and root caries sensitivity. Treatment of lichen planus, candidal infections, angular cheilitis, xerostomia, orthodontic traumatic ulcers, erupting teeth, pulp capping, temporary restorations and dressings, covering tooth preparations, mummifying caries decidous teeth, Socket ‘covering’ after extraction, dry socket (similar to ‘bone wax’ and Whitehead's varnish), Pre-anesthetic (topical), Periocoronitis, etc.[1–4] Propolis also has clinical applications in medicine/surgery, for e.g,. anti-asthmatic treatment in mouth sprays, support of pulmonary system, anti-rheumatic, inhibition of melanoma and carcinoma tumor cells, tissue regeneration, strengthening of capillaries, anti-diabetic activity, phytoinhibitor, etc.[5–7]

Propolis extract is known to possess antimicrobial activity against Streptococcus mutans, a Gram-positive cocci, facultative anaerobic bacterium commonly found in the human oral cavity and a significant contributor to tooth decay. The extract might be used as an alternative measure to prevent dental caries. Propolis has also been evaluated for antimicrobial activity as an intracanal medicament, and has shown promising results. Propolis has been found beneficial in the treatment of gingivitis and oral ulcers in several small case studies and pilot clinical studies.[8] In addition to the treatment of periodontopathies, preparations with propolis have been found to be antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, have antiscar effects, and to be highly antimycotic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study was carried out to investigate the effectiveness of a propolis-containing mouthrinse in inhibition of plaque formation and improvement of gingival health. This clinical study was conducted in Department of Periodontics, I.T.S.-C.D.S.R., Muradnagar, Ghaziabad, Uttar Pradesh. The study was designed as a single blind three-group parallel study of 5-day de novo plaque formation. Three mouthrinses were compared: The test mouthrinse containing the active ingredient propolis [Figures 1–4], a placebo mouthrinse (saline) and a positive control mouthwash - chlorhexidine. Inclusion criteria were – 30 patients with age group of 18 to 50 years with chronic generalized gingivitis, patient free from systemic illness. Exclusion criteria were pregnant and nursing patients, inability to comply with the follow-up visit requirements, and patients receiving concurrent antibiotic treatment for any other purpose. Parameters noted were- Plaque index (Turesky-Gilmore, 1970) at baseline and at a five-day interval, gingival index (Loe and sillness, 1963) at baseline and at a five-day interval. Comparative photographs of the three group patients are shown in Figures 5–7.

Figure 1.

Raw propolis

Figure 4.

Final propolis extract used as a mouthwash

Figure 5.

Patient appearance at 5-day interval after use of disclosing agent (chlorhexidine group)

Figure 7.

Patient appearance at 5-day interval after use of disclosing agent (propolis group)

Figure 2.

Raw propolis being dissolved

Figure 3.

Propolis being extracted

Figure 6.

Patient appearance at 5-day interval after use of disclosing agent (saline group)

Thirty subjects were selected and randomly assigned into three groups of ten subjects each, which received a propolis-containing mouthrinse, or a negative control (Saline) or a positive control (Chlorhexidine 0.2%). Three weeks prior to commencing the study, all subjects had their teeth professionally scaled and polished. Oral hygiene instructions were given in an attempt to improve their oral hygiene before entry into the study. Plaque index (Turesky-Gilmore, 1970) and gingival index (Loe and Sillness, 1963) were assessed at baseline and at a five-day interval.

The mouthrinses were allocated according to groups to ensure balance. All subjects were instructed to rinse two times a day with the mouthrinse for one min and to refrain from all other oral hygiene measures until the final examination, five days later. At the final examination plaque and gingival scores were recorded as previously. The data was then subjected to statistical analysis.

RESULTS

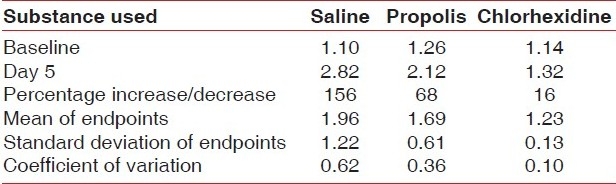

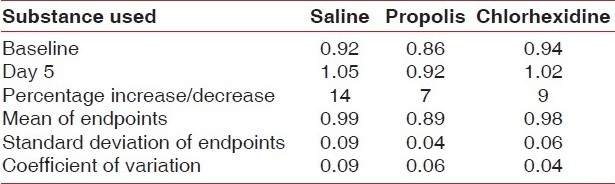

All the patients successfully completed the study. The two mouthwashes were found to be equally effective in decreasing the plaque index [Table 1, Figure 8]. The two-tailed p-value equaled 0.5392; this difference was considered to be not statistically significant. The two treatment groups were equally effective in decreasing the gingival index [Table 2, Figure 9]. The two-tailed P-value equaled 0.0048; this difference was considered to be very statistically significant. Results showed a highly significant statistical change with regard to improvement in the gingival inflammation when compared to both the positive and negative controls. The result was not statistically significant for plaque accumulation.

Table 1.

Plaque index

Table 2.

Gingival index

DISCUSSION

Propolis is the resinous substance collected by bees from the leaf buds and bark of trees, especially poplar and conifer trees. Bees use the propolis along with beeswax to construct their hives. Propolis has antibiotic activities that help the hive block out viruses, bacteria, and other organisms. Commercial preparations of propolis appear to retain these antibiotic properties, according to test tube studies.[9,10] Test tube and animal studies have also shown that propolis exerts some antioxidant,[11] liver protecting,[12] anti-inflammatory,[13–15] and anticancer properties.[16]

Besides showing antimicrobial activity against periodontopathic bacteria, the propolis extract does not demonstrate selection of superinfectant organisms. Propolis mechanism of antimicrobial action, though not completely understood, seems to be complex and may vary according to its composition. The compounds known to have antimicrobial action are mainly the flavonoids and cinamic acids.[17]

As an anti-inflammatory agent, propolis is shown to inhibit synthesis of prostaglandins, activate the thymus gland, aid the immune system by promoting phagocytic activity, stimulate cellular immunity, and augment healing effects on epithelial tissues. Additionally, propolis contains elements, such as iron and zinc that are important for the synthesis of collagen.[18]

Propolis contains protein, amino acids, vitamins, minerals, and flavonoids.[19–21] for this reason; some people use propolis as a general nutritional supplement, although it would take large amounts of propolis to supply meaningful amounts of these nutrients. Propolis may stimulate the body's immune system, according to preliminary human studies,[22,23] and a controlled trial found propolis-containing mouthwash effective in healing surgical wounds in the mouth.[24] In test tube studies, propolis has shown considerable activity against bacteria and yeast associated with dental cavities, gingivitis, and periodontal disease,[25,26] but one human study showed that propolis was no better than a placebo in inhibiting dental plaque formation.[27]

The results of a study to investigate the effectiveness of a propolis-containing mouthrinse in the inhibition of de novo plaque formation are presented. Subjects used a propolis-containing rinse, a negative control, and a positive control in a double-blind, parallel, de novo plaque formation study design. The chlorhexidine mouthrinse was significantly better than the others in plaque inhibition. The propolis-containing rinse was marginally better than the negative control, but this difference was not significant.[27]

Koo et al. carried a study to evaluate the effect of a mouthrinse containing propolis on 3-day dental plaque accumulation. Six volunteers took part in a double-blind crossover study performed in two phases of 3 days. During each phase the volunteers refrained from all oral hygiene and rinsed with 20% sucrose solution 5 times a day to enhance dental plaque formation and with mouthrinse (placebo or experimental) twice a day. On the 4th day, the plaque index (PI) of the volunteers was scored and the supragingival dental plaque was analyzed for insoluble polysaccharide (IP). The PI (SD) for the experimental group was 0.78 (0.17), significantly less than for the placebo group, 1.41 (0.14). The experimental mouthrinse reduced the IP concentration in dental plaque by 61.7% compared to placebo (P<0.05). An experimental mouthrinse containing propolis was thus efficient in reducing supragingival plaque formation and IP formation under conditions of high plaque accumulation.[28]

The present study evaluated the effect of propolis mouthwash on plaque accumulation and gingivitis. This was done by comparing the plaque and gingival indices at baseline and 5-day interval, and the mouthwash was compared with both positive and negative controls. Saline showed 156% increase, propolis showed 68%, and chlorhexidine showed 16% increase in plaque index on the 5th day. Saline showed 14% increase, propolis showed 7%, and chlorhexidine showed 9% increase in gingival index on the 5th day. It appears from the above data that propolis is not better than chlorhexidine in reducing plaque formation, but may be marginally better for reduction of gingival inflammation. This is in accordance with studies by Murray et al, 1997[27] and Koo et al, 1999[28]

Long term studies on propolis are relatively few in number. Recently, Mahmoud et al. have conducted a pioneer study on the effect of propolis on dentinal hypersensitivity in vivo. The clinical trial of propolis on female subjects for four weeks was conducted at King Saud University, College of Dentistry, Riyadh. Twenty-six female subjects with age range 16–40 years (mean age 28 years) were included in the study. Propolis was applied twice daily on teeth with hypersensitivity. The hypersensitivity was assessed on a visual scale 0−10 and by slight, moderate and severe classification at baseline, after 1 and 4 weeks. Seventy percent of the subjects had severe hypersensitivity at the baseline. At first recall, 50% reported moderate hypersensitivity, fifty percent reported slight hypersensitivity at second recall and 30% had no hypersensitivity while only 19% had moderate hypersensitivity. It was concluded that propolis had a positive effect in the control of dentinal hypersensitivity.[29,30]

One study by Mani et al has investigated the biochemical profile of propolis-treated rats to observe whether propolis might lead to side effects after administration. Three different treatments were analyzed: (1) rats were treated with different concentrations of propolis (1, 3, and 6 mg/kg/day) during 30 days; (2) rats were treated with 1 mg/kg/day of ethanolic or water extracts of propolis (EEP, WEP) during 30 days; (3) rats were treated with 1 mg/kg/day of ethanolic extract of propolis during 90 and 150 days. Our results demonstrated no alterations in the seric levels of cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, total lipids, triglycerides, and in the specific activity of aminotransferases (AST) and lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) of propolis-treated groups when compared to controls. On the basis of their findings, since propolis does not induce any significant change in seric parameters, it is claimed that long-term administration of propolis might not have any cardiac injury.[31]

CONCLUSION

Propolis is a subject of recent dentistry research, since there is some evidence that propolis may actively protect against oral disease due to its antimicrobial properties. Propolis can also be used to treat canker sores. Its use in canal debridement for endodontic procedures has been explored. Because of its strong, anti-infective activity, propolis has often been called a “natural antibiotic.” Many studies show its strong inhibitory effect on a wide variety of pathogenic organisms. It may be concluded from the above study that the propolis extract tested possesses anti-plaque activity and improves gingival health. The extract might be used as an alternative measure to prevent periodontal and gingival problems. Further, long term trials are required with a larger sample.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Park YK, Koo MH, Ikegaki M, Cury JA, Rosalen PL. Effects of propolis on Streptococcus mutans, Actinomyces naeslundii, Staphylococcus aureus. Rev Microbiol. 1998;29:143–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ikeno K, Ikeno T, Miyazawa C. Effects of propolis on dental caries in rats. Caries Res. 1991;25:347–51. doi: 10.1159/000261390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koo H, Rosalen PL, Cury JA, Park YK, Ikegaki M, Sattler A. Effects of Apis mellifera propolis from Brazilian regions on caries development in desalivated rats. Caries Res. 1999;33:393–400. doi: 10.1159/000016539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bretz WA, Chiego DJ, Jr, Marducci MC, Cunha I, Custódio A, Shneider LG. Preliminary report on the effects of propolis on wound healing in the dental pulp. Z Naturforsch C. 1998;53:1045–8. doi: 10.1515/znc-1998-11-1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brumfitt W, Hamilton-Miller JM, Franklin I. Antibiotic activity of natural products: 1. Propolis. Microbios. 1990;62:19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dimov V, Ivanovska N, Manolova N, Bankova V, Nikolov N, Popov S. Immunomodulatory action of propolis. Influence on anti-infectious protection and macrophage function. Apidologie. 1991;22:155–62. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dobrowolski JW, Vohora SB, Sharma K, Shah SA, Naqvi SA, Dandiya PC. Antibacterial, antifungal, antiamoebic, antiinflammatory and antipyretic studies on propolis bee products. J Ethnopharmacol. 1991;35:77–82. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(91)90135-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martínez Silveira G, Gou Godoy A, Oña Torriente R, Palmer Ortiz MC, Falcón Cuéllar MA. Preliminary study of the effects of propolis in the treatment of chronic gingivitis and oral ulceration. Rev Cubana Estomatol. 1998;25:36–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tosi B, Donini A, Romagnoli C, Bruni A. Antimicrobial activity of some commercial extracts of propolis prepared with different solvents. Phytother Res. 1996;10:335–6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dobrowski JW, Vohora SB, Sharma K, Shah SA, Naqvi SA, Dandiya PC. Antibacterial, antifungal, antiamoebic, antiinflammatory and antipyretic studies on propolis bee products. J Ethnopharmacol. 1991;35:77–82. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(91)90135-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pascual C, Gonzalez R, Torricella RG. Scavenging action of propolis extract against oxygen radicals. J Ethnopharmacol. 1994;41:9–13. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(94)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin SC, Lin YH, Chen CF, Chung CY, Hsu SH. The hepatoprotective and therapeutic effects of propolis ethanol extract on chronic alcohol-induced liver injuries. Am J Chin Med. 1997;25:325–32. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X97000366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dobrowski JW, Vohora SB, Sharma K, Shah SA, Naqvi SA, Dandiya PC. Antibacterial, antifungal, antiamoebic, antiinflammatory and antipyretic studies on propolis bee products. J Ethnopharmacol. 1991;35:77–82. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(91)90135-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khayyal MT, El-Ghazaly MA, El-Khatib AS. Mechanisms involved in the antiinflammatory effect of propolis extract. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1993;29:197–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirzoeva OK, Calder PC. The effect of propolis and its components on eicosanoid production during the inflammatory response. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1996;55:441–9. doi: 10.1016/s0952-3278(96)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi YH, Lee WY, Nam SY, Choi KC, Park YE. Apoptosis induced by propolis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line. Int J Mol Med. 1999;4:29–32. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.4.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bankova V, Christov R, Kujumgiev A, Marcucci MC, Popov S. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of brazilian propolis. Z Naturforschung C. 1995;50:167–72. doi: 10.1515/znc-1995-3-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Özana F, Sümerb Z, Polatc ZA, Erd K, Özane U, Değerf O. Effect of Mouthrinse Containing Propolis on Oral Microorganisms and Human Gingival Fibroblasts. Eur J Dent. 2007;1:195–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreira TF. Chemical composition of propolis: Vitamins and amino acids. Rev Bras Farmacogn. 1986;1:12–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker P, Crane E. Constituents of propolis. Apidologie. 1987;18:327–34. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stangaciu S. Constanta, Romania: Dao Publishing House; 1997. A guide to the composition and properties of propolis. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bratter C, Tregel M, Liebenthal C, Volk HD. Prophylactic effectiveness of propolis for immunostimulation: A clinical pilot study. Forsch Komplementarmed. 1999;6:256–60. doi: 10.1159/000021260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crisan I, Zaharia CN, Popovici F, Jucu V, Belu O, Dascălu C, et al. Natural propolis extract NIVCRISOL in the treatment of acute and chronic rhinopharyngitis in children. Rom J Virol. 1995;46:115–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magro-Filho O, de Carvalho AC. Topical effect of propolis in the repair of sulcoplasties by the modified Kazanjian technique.Cytological and clinical evaluation. J Nihon Univ Sch Dent. 1994;36:102–11. doi: 10.2334/josnusd1959.36.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinberg D, Kaine G, Gedalia I. Antibacterial effect of propolis and honey on oral bacteria. Am J Dent. 1996;9:236–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park YK, Koo MH, Abreu JA, Ikegaki M, Cury JA, Rosalen PL. Antimicrobial activity of propolis on oral microorganisms. Curr Microbiol. 1998;36:24–8. doi: 10.1007/s002849900274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murray MC, Worthington HV, Blinkhorn AS. A study to investigate the effect of a propolis-containing mouthrinse on the inhibition of de novo plaque formation. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:796–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb01191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koo H, Cury JA, Rosalen PL, Ambrosano GM, Ikegaki M, Park YK. Effect of a Mouthrinse Containing Selected Propolis on 3-Day Dental Plaque Accumulation and Polysaccharide Formation. Caries Res. 2002;36:445–8. doi: 10.1159/000066535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahmoud A, Almas K, Dahlan A. The effect of Propolis on female subjects with dentinal hypersensitivity. J Dent Res. 2000;79:406. (Abst # 2097) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahmoud AS, Almas K, Dahlan AA. The effect of Propolis on dentinal hypersensitivity and level of satisfaction among patients from a university hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Indian J Dent Res. 1999;10:130–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mani F, Damasceno HC, Novelli EL, Martins EA, Sforcin JM. Propolis: Effect of different concentrations, extracts and intake period on seric biochemical variables. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;105:95–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]