Abstract

Objectives:

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate and compare the relationship between the levels of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) in gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) and saliva, both clinically and biochemically, in patients with and without chronic periodontitis.

Materials and Methods:

For this study, 36 patients (12 male, 24 female) were selected in the age range of 18-60 years (mean, 32.7±11.1 years). The subjects were assigned to three groups, which included Group I (control), Group II (chronic periodontitis with probing depth PD <5 mm), and Group III (chronic periodontitis with PD ≥5 mm). Clinical parameters included plaque index, gingival index, sulcus bleeding index, PD, and clinical attachment level. The GCF samples were taken by using the capillary tubes whereas saliva was collected by the suction method. The levels of HGF in GCF and in saliva were estimated using an enzyme linked immunosorbant assay reader.

Results:

There was a significant correlation in the levels of HGF in GCF and in saliva of patients with and without chronic periodontitis. The results also indicated that the HGF levels in GCF and saliva correlated well with the clinical parameters and with the severity of the periodontal disease.

Conclusion:

Both GCF and saliva can be used to estimate the levels of HGF and thus may be regarded as a novel marker for periodontal disease activity.

Keywords: Gingival crevicular fluid, hepatocyte growth factor, periodontal disease, saliva

INTRODUCTION

Traditional periodontal diagnosis involves retrospective diagnosis of periodontal attachment and bone loss. For these reasons, a large proportion of recent periodontal research base has been concerned with finding and testing the potential markers of periodontal disease activity.[1] In the disease process, potential biomarkers of disease activity would need to be involved in some way as a consequence of tissue damage during disease progression. Gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) components that are the result of these processes have been the main source for the study. The most specific sign of connective tissue breakdown may be the protein concentration of GCF.[2]

The GCF contains a variety of mediators or markers of the periodontal disease activity and complement component cytokines. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) is one such factor, also known as scatter factor (SF). This cytokine is now known to play an important role in the regulation of both normal physiological processes as well as the pathological ones. It is an important mediator of epithelial mesenchymal cell interaction with potential involvement in organogenesis, Angiogenesis, and tumor progression. HGF/SF was originally identified and characterized as two different factors, one with growth-stimulating activity (HGF) and other with scatter factor activity (SF). These two activities were subsequently ascribed to the same factor.[3]

The role of HGF in periodontitis was reported following the reports of loss of connective tissue attachment in periodontitis cases thus suggesting that HGF may be involved in epithelial invasion through its role as a SF. Recently, Ohshima et al.[4] detected a much greater amount of HGF/SF in GCF than that found in normal human serum. Similarly, HGF levels in saliva were found to be elevated in periodontal disease status, and were well correlated with clinical parameters such as probing depths (PDs) and sites positive for bleeding on probing.[5]

Ohshima et al.,[6] in their study on role of HGF system in epithelial invasion, suggested that synergistic expression of HGF in connective tissue and hepatocyte growth factor activator (HGFA) expression in epithelium may contribute to disease progression in periodontitis.

In view of these observations, it seems likely that HGF plays a role in periodontal disease. The purpose of this study was to investigate the presence of HGF/SF in GCF and saliva and comparatively correlate their relationship with clinical parameters of healthy gingiva and chronic periodontitis using the recently developed highly sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay (ELISA) test kit.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 36 patients (12 male, 24 female) in the age range of 18–60 years were selected from the Out Patient Department of Periodontology and Implantology, Bapuji Dental College and Hospital, Davangere, Karnataka state, based on the following selection criteria:

Patient selection criteria

-

(1)

Only systemically healthy patients.

-

(2)

Patients having periodontal status ranging from clinically healthy to diseased, as follows:

-

(a)Twelve patients in the age group of 18–25 years having clinically healthy gingiva with no signs of gingival inflammation were selected for Group I.

-

(b)Twelve chronic periodontitis patients in the age group of 35–60 years having probing pocket depth <5 mm, with bleeding on probing and radiographic evidence of bone loss on at least two teeth in a minimum of two quadrants for Group II.

-

(c)Twelve chronic periodontitis patients in the age group of 35–60 years having probing pocket depth of 5 mm or more than 5 mm, with bleeding on probing positive and radiographic evidence of bone loss on at least two teeth in a minimum of two quadrants were selected for Group III.

-

(a)

-

(3)

Intake of any antibiotics and regular use of anti-inflammatory medication or the use of other drugs known to affect the periodontium in the past 6 months were excluded.

A total of 72 samples (GCF – 36 and saliva – 36) were collected.

Clinical parameters

The following parameters were recoded after the selection of the test sites:

Plaque index (PI)[7]

Gingival index (GI)[8]

Sulcus bleeding index (SBI)[9]

Probing pocket depth measured using the Williams graduated periodontal probe

Clinical attachment level (CAL) recorded using a customized acrylic stent and calibrated silver point

Radiographs with evidence of bone loss were confirmed by intraoral periapical radiographs

Determination of hepatocyte growth factor in gingival crevicular fluid and saliva

Selection of the test site and recording of the clinical parameters was undertaken one day before the collection of GCF. Extracrevicular method was used for the collection of GCF, where the sampling device was placed at the orifice of the gingival crevice.[10] A standard volume of 1.2 μl of GCF was collected in a glass capillary tube with an internal diameter of 1.0 mm, as described by Sueda et al.[11] The collected fluid was immediately transferred into a microcentrifugation plastic tube containing 60 μl of calibration diluent RD6X.

For saliva collection, the suction method as described by Navesh[12] was used. Patients were asked to rinse their mouth thoroughly with deionized water, tilt their head slightly forward, and rest for 5 min as adovocated by Rahim.[13] The unstimulated whole saliva (0.5–2 ml) was aspirated from the floor of the mouth and kept on ice for not more than 2 h. It was then centrifuged and the supernatant was collected and used for the assay as proposed by Ohshima et al.[5]

HGF levels in GCF and saliva were determined using an ELISA kit (Quantikine human HGF immunoassay; R and D System, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions at room temperature. An ELISA reader was used to record the optical density (OD) of the tested samples. The method used was based upon the procedure adopted by Ohshima et al.[4]

All the reagents and samples were brought to room temperature before use. The required microplate strips from the plate frame were used and the remaining were returned to the foil pouch containing the desiccant pack and resealed. Addition of 150 ml of Assay Diluent RD1W per well was made. Addition of 50 ml of standard or sample per well was made, ensuring that reagent addition was uninterrupted and completed within 15 min. This was followed by mixing by gently tapping the plate. This was then covered with the adhesive strip provided and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Aspiration and washing from each well was made and the process was repeated for a total of four washes. Washing was performed by filling each well with the wash buffer (400 μl) using a squirt bottle. After the last wash, the remaining wash buffer was removed by aspirating or decanting. This was followed by inverting the plate and blotting it against clean paper toweling. Addition of 200 ml of the HGF conjugate to each well was made and then covered with two new adhesive strips. Incubation for 2 h was made at room temperature. Aspiration/washing was repeated. Addition of 200 μl of substrate solution was made to each well. It was incubated for 30 min at room temperature and was protected from light. Addition of 50 μl of stop solution to each well was made and the color change appeared. Determination of the OD of each well within 30 min was made using two microplate readers set to 450 nm.

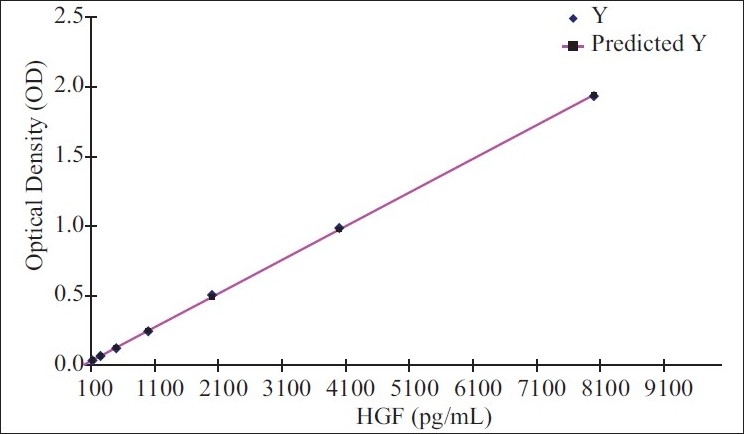

The readings for each standard, control, and sample were taken and the average zero standard OD was subtracted. A standard curve was constructed by plotting the absorbance (optical dentistry) for each standard on the Y-axis against the concentration on the X-axis. The data was linearized by plotting the log of the HGF concentrations versus the log of the OD, and the best fit line was determined by regression analysis [Figure 1]. Standard OD with known concentration of HGF/SF (pg/μl) was used to derive a regression equation for calculation of HGF/SF (pg/μl) concentration for a given OD, i.e. HGF/SF (pg/ μl) = –30.1 + 4130 (OD). The results of the study were subjected to statistical analysis.

Figure 1.

X Variable 1 line fit plot

Statistical analysis

The values obtained were presented as range, mean, and standard deviation. The ANOVA technique was used for multiple groups comparisons followed by the Mann–Whitney test for group-wise comparisons. Relationship between various clinical parameters and HGF was assessed by Pearson's correlation coefficient and a P-value of 0.05 or less was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

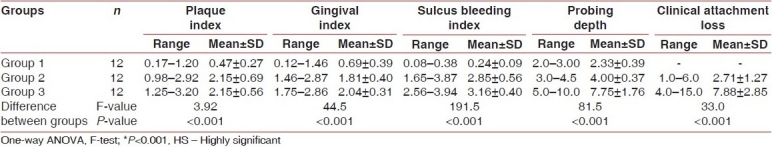

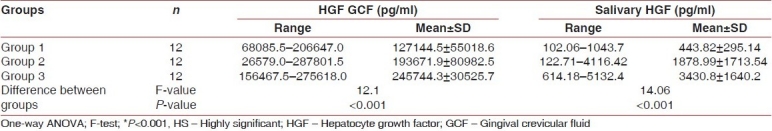

A significant increase in PI, GI, SBI, PD, CAL, HGF/SF level in GCF, and HGF/SF level in saliva was observed between the healthy and diseased sites, as shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and comparison of clinical parameters in Group 1, Group 2, and Group 3

Table 2.

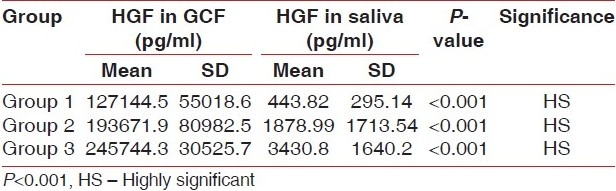

Descriptive statistics and comparison of GCF, HGF and salivary HGF levels in Group 1, Group 2, and Group 3

In the present study, when the HGF/SF level in saliva was compared between Group I and Group II, the difference in the mean HGF/SF level in saliva was marginally significant (P<0.05). However, on comparison between Group I and Group III, the mean difference was highly significant (P<0.001). Also, while comparing the HGF/SF level in saliva between Group II and Group III, the mean difference between the two groups was statistically significant (P<0.01). The ANOVA test revealed that different study groups showed difference in the mean HGF/SF level in the saliva, which was statistically highly significant (F=14.06, P<0.001).

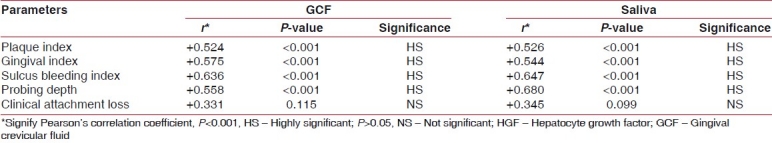

When correlation of HGF/SF levels in GCF was made with PI, GI, and SBI in Group I, Group II, and Group III cases, the Pearson's correlation coefficient were found to be +0.524, +0.575, and +0.636, respectively, for all the three parameters, which were statistically highly significant (P<0.001). Furthermore, when correlation of HGF/SF levels in GCF was made with PD in Group I, Group II, and Group III cases, the Pearson's correlation coefficient was found to be +0.558, which was statistically highly significant (P<0.001). However, when the correlation of HGF/SF levels in GCF was made with clinical attachment loss, in Group II and Group III cases, the Pearson's correlation coefficient was found to be +0.331, which was statistically not significant (P=0.115). When correlation of HGF/SF levels in saliva was made with PI, GI, and SBI in Group I, Group II, and Group III cases, the Pearson's correlation coefficient was found to be +0.526, +0.544, and +0.647, respectively, for all the three parameters, which were statistically highly significant (P<0.001). When correlation of HGF/SF levels in saliva was made with PD in Group I, Group II, and Group III cases, the Pearson's correlation coefficient was found to be +0.680, with P<0.001, which was statistically highly significant. However, when the correlation of HGF/SF levels in saliva was made with clinical attachment loss, in Group II and Group III patients, the Pearson's correlation coefficient was found to be +0.345, which was statistically not significant (P=0.099) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Correlation of HGF levels in GCF and HGF levels in saliva with different parameters in combined Group 1, Group 2, and Group 3

In Group I (control) cases, when comparison of HGF/SF level in GCF and in saliva was made, the mean value for GCF HGF and salivary HGF was found to be 127144.5±55018.6 pg/ml and 443.82±295.14 pg/ml, respectively. The Mann-Whitney test revealed a significant (P<0.001) difference. However, in Group II cases (PD ≥5 mm with chronic periodontitis), when comparison of HGF/SF level in GCF and in saliva was made, the mean value for GCF HGF and salivary HGF was found to be 193671.9±80982.5 pg/ml and 1878.99±1713.5 pg/ ml, respectively. The Mann-Whitney test revealed a highly significant (P<0.001) difference. Similarly, in Group III cases (PD 5 mm with chronic periodontitis), when comparison of HGF/SF level in GCF and in saliva was made, the mean value for GCF HGF and salivary HGF was 245744.3±30525.7 pg/ml and 3430.8±1640.2 pg/ml, respectively. The Mann-Whitney test revealed a highly significant (P<0.001) difference [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparison of HGF levels in GCF and in saliva in Group 1, Group 2, and Group 3

DISCUSSION

Current periodontal research is the search for diagnostic tests of periodontal disease activity. These include by-products of the host bacterial interactions like aspartate aminotransferase, β-glucoronidase, Cathepsin-G, etc. HGF is one such factor that acts as a motogen through its role as SF, which is released in response to inflammation during periodontal destruction. This factor has been closely correlated with the severity of the chronic periodontitis. HGF levels in GCF could be used as a sensitive marker for periodontal disease status. It has been positively correlated with clinical parameters such as PI, GI, bleeding on probing, and PD.[4]

The use of saliva for periodontal diagnosis has been the subject of considerable research activity, and the proposed markers for disease include proteins of host origin (i.e., enzymes. immunogobulins), phenotypic markers (epithelial keratins), host cells, hormones (cortisol), bacteria and bacterial products, volatile compounds, and ions.[14] It has been postulated that analysis of the whole saliva holds greater promise than gland-specific saliva when considering the development of a diagnostic test for periodontal disease.[15] Salivary levels of HGF have been positively correlated with clinical parameters like bleeding on probing and PD, and it has been suggested that salivary HGF may be a novel marker for periodontal diagnosis.[5]

Clinical parameters like PI, GI, SBI, PD, and CAL, which reflect the gingival and periodontal status in health and disease, were considered. The plaque score, GI, gingival bleeding (SBI score), and the PD for Group I (control) patients was recorded to be minimum than that in Group II (chronic periodontitis with pocket depth ≥5 mm) patients and maximum for the Group III (chronic periodontitis with pocket depth ≥5 mm) patients. The clinical attachment loss was greater for the Group III than the Group II patients. The HGF/SF was detected in GCF and saliva in all the three groups. It was minimum for the Group I (control) patients and maximum for the Group III (chronic periodontitis) patients. Both the GCF and the salivary HGF are increased with increasing severity of inflammation/infection and are directly related to all the clinical parameters of assessing chronic periodontitis. Correlation between subject age and related HGF levels revealed no correlations between these two factors.

The results in the present study support the hypothesis that the GCF is one of the major sources of HGF in the whole (mixed) saliva, and it is directly related to the severity of periodontal disease. Because the whole (mixed) saliva represents a combination of fluids from the major and minor salivary glands as well as from the GCF, these various sources could contribute differentially to the HGF, i.e. perhaps not all HGF is of GCF origin. Hence, our study indicated that the HGF in whole (mixed) saliva may be a novel marker for periodontal health and disease.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eley BM, Cox SW. Advances in periodontal diagnosis: 1: Traditional clinical methods of diagnosis. Br Dent J. 1998;184:12–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attstrom R, Laural AB, Lashsson V. Complement factors in gingival crevice material from healthy and inflamed gingiva in humans. J Periodontal Res. 1974;10:19–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1975.tb00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gherardi E, Stoker M. Hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor. Cancer Cells. 1991;3:227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oshima M, Sakai A, Ito K, Otsuka K. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) in periodontal disease; Detection of HGF in gingival crevicular fluid. J Periodontal Res. 2002;37:8–14. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2002.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oshima M, Fugikawa K, Akutagawa HT, Ito K, Otsuka K. Hepatocyte growth factor in saliva: A possible marker for periodontal disease status. J Oral Sci. 2002;44:35–9. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.44.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oshima M, Saka A, Sawamoto Y, Seki K, Ito K, Otsuka K. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) system in gingiva: HGF activator expression by gingival epithelial cells. J Oral Sci. 2002;44:129–34. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.44.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silness J, Loe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy II.Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal conditions. Acta Odont Scand. 1964;22:112–34. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy I: Prevalence and severity. Acta Odont Scand. 1963;21:533–51. doi: 10.3109/00016356309011240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muhlemann HR, Son S. Gingival sulcus bleeding: A leading symptom in initial gingivitis. Hev Odontol Acta. 1971;15:107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loe H, Holm-Pederson P. Absence and presence of fluid from normal and inflamed gingiva. Periodontics. 1965;3:171–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sueda T, Bang J, Cimasoni G. Collection of gingival fluid for quantitative analysis. J Dent Res. 1969;48:159–62. doi: 10.1177/00220345690480011501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Navesh M. Methods for collecting saliva. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1993;69:72–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb18343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rahim ZH. Saliva in research and clinical diagnosis: An overview. Ann Dent Univ Malaya. 1998;5:11–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mandel ID. Markers of periodontal disease susceptibility and activity derived from saliva. In: Johnson NW, editor. Risk markers for oral diseases. Periodontal diseases: Markers of disease susceptibility and activity. Vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1991. pp. 228–53. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaufman E, Lamster IB. Analysis of saliva for periodontal diagnosis: A review. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:453–65. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027007453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]