Abstract

Gingival melanin pigmentation occurs in all races of mankind. Although clinical melanin pigmentation does neither present itself as a medical problem nor a disease entity, it is a major esthetic concern for many people, especially Asians. Esthetic gingival depigmentation procedures can be performed in such patients with excellent results. This case series presents a split mouth de-epithelization procedure using popular surgical techniques such as scalpel, bur abrasion or electrosurgery. These techniques were successfully used to treat gingival hyperpigmentation. Although we found that electrosurgery increased the efficacy of our work, giving a cleaner and neater work field, it required a lot of precision. In contrast, scalpel de-epithelization was easy and technique-friendly, giving excellent results and patient satisfaction. However, the cases are being followed-up to study the factors affecting the rate and length of time required for repigmentation and to study the repigmentation patterns. This case series also reviews the advantages and disadvantages of various techniques available for depigmentation, and reiterates that the scalpel technique still serves as a gold standard for depigmentation.

Keywords: Bur abrasion, depigmentation, electrosurgery, gingiva, melanin, physiological pigmentation, scalpel technique

INTRODUCTION

The color of the gingiva is determined by several factors, namely number and size of the blood vessels, epithelial thickness, quantity of keratinization and pigments within the gingival epithelium. Melanin, carotene, reduced hemoglobin and oxyhemoglobin are the main pigments contributing to the normal color of the oral mucosa.[1] Melanin, a brown pigment, is the most common natural pigment contributing to endogenous pigmentation of the gingiva. Physiological pigmentation of the oral mucosa (mostly gingiva), is clinically manifested as multifocal or diffuse melanin pigmentation with variable amounts in different ethnic groups worldwide[2,3] and it occurs in all races.[2,4] Melanin is deposited by melanocytes, mainly located intertwined between the basal and the suprabasal cell layers of epithelium,[5,6] often observed to a greater degree at the incisors.[7] In Caucasians, most melanocytes have striated granules that are incompletely melanized and vary in size from 0.1 to 0.3 mm. But, the amount is insufficient to cause pigmentation (less than 10% demonstrate pigmentation). A high amount of melanin granules is found in individuals of African and East Asian ethinicity.[8] In them, the granules are more completely melanized and form larger complexes of size about 1–3 µm; hence, clinical pigmentation is evident. Therefore, the size and degree of melanization of these granules is directly proportional to the degree of pigmentation.[7] Also, there appears to be a positive correlation between gingival pigmentation and degree of dermal pigmentation.[9] However, melanin pigmentation of the gingiva is symmetric and does not alter the normal gingival architecture.[2]

In dark-skinned and black individuals, an increased melanin production has long been known to be the result of genetically determined hyperactivity of melanocytes. Melanocytes of dark skinned and black individuals are uniformly highly reactive, whereas in light skinned individuals, melanocytes are highly variable in reactivity.[10,11] In general, individuals with fair complexion will not demonstrate overt tissue pigmentation, even though comparable numbers of melanocytes are present within their gingival epithelium.[12]

Brown or dark pigmentation or discoloration of the gingival tissue is however considered as multifaceted etiology, including genetic factors[8] (irrespective of age[2,4] and gender;[13] hence, termed physiologic or racial pigmentations[2,14] ), tobacco use,[15,16] systemic disorders[17] (endocrine disturbance, Albright's syndrome, malignant melanoma, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, hemachromatosis, chronic pulmonary disease, Addison's syndrome and von Recklinghausen's disease [neurofibromatosis]),[17,18] antimalarial therapy,[19,20] tricyclic antidepressants and a variety of local and systemic factors.[21]

Clinical melanin pigmentation is completely benign and does not present a medical problem, although complaints of dark gums may pose an esthetic concern, particularly if visible during speech and smiling[22] Demand for cosmetic therapy is made, especially by fair skinned people with moderate or severe gingival pigmentation,[23] mostly in patients with a high smile line (gummy smile). Gingival depigmentation is a periodontal plastic surgical procedure whereby the gingival hyperpigmentation is removed or reduced by various techniques.

CASE PRESENTATIONS

Six patients [four male, two female [Figure 1], all students, aged 19–25 years visited the Department of Periodontics, Government Dental College and Research Institute, Bangalore, India, with the chief complaint of “dark gums” with loss of confidence and embarrassment within their peer groups. Two patients requested for any cosmetic therapy that would eventually enhance the esthetics on smiling; the other four were referred cases. The patients’ history revealed that the blackish discoloration of gingiva was present since birth, suggestive of physiologic melanin pigmentation. Clinical examination revealed pronounced bilateral melanin pigmentation associated with a healthy periodontium. Their medical history was non-contributory. The patients were in good general health and there were no contraindications for the surgeries. All depigmentation areas were graded from 1 to 10 according to the “Weinman” scale of grading gingival depigmentation. Considering the patient's concern, a split mouth surgical gingival de-epithelization procedure was decided. A combination of scalpel de-epithelization, bur abrasion or electrosurgery was planned [Figures 2–7].

Figure 1.

Baseline (Left to right). Patient 1: 20 years male (Weinman score 10) Patient 2: 25-years-old male (Weinman score 7), 12 weeks post-treatment after scalpel de-epithelization Patient 3: 20 years female (Weinman score 10) Patient 4: 22 years female (Weinman score 10) Patient 5: 21 years male (Weinman score 10) Patient 6: 19 years male (Weinman score 10)

Figure 2.

Patient 2 – Bur abrasion (II quadrant) on the contralateral side after scalpel de-epithelization (I quadrant, not shown)

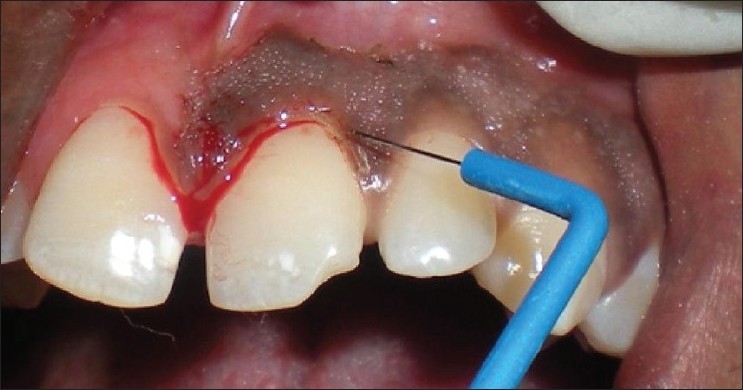

Figure 7.

Patient 6 – Needle electrode used to give incisoin, mesial incision was given with a scalpel to avoid demarkation between the contralateral side

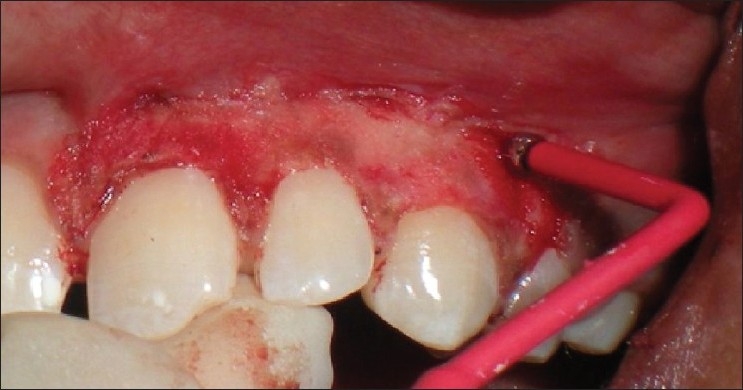

Figure 5.

Patient 5 – Diamond bur abrasion (I quadrant)

Surgical procedure

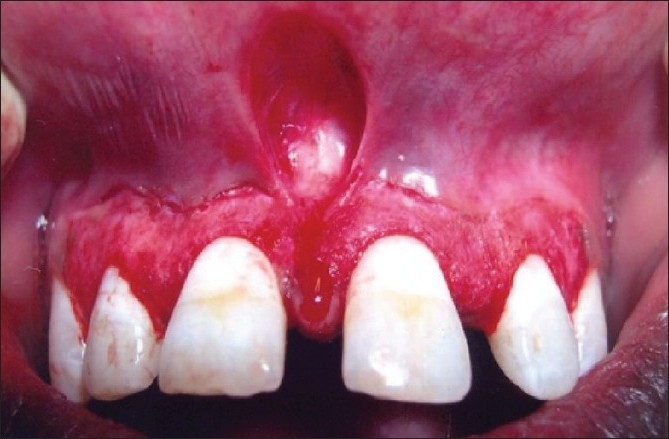

About 2 ml of Lignocaine adrenaline local anesthesia was administered as nerve block and/or infiltration. Two vertical incisions were made on the side destined to undergo scalpel de-epithelization (both distally and mesially) of the pigmentated area using a #15 scalpel blade. A split thickness flap was raised and excised, maintaining the normal architecture of the gingiva [Figures 3, 4 and 6]. Bleeding was controlled using pressure pack with sterile gauze. Sterile saline-soaked gauze was placed on the recipient site to control bleeding. The exposed depigmented surface was covered with Coe-pak periodontal dressing for 1 week. The patient was prescribed Amoxicillin 500 mg, TD for 5 days and Aceclofenac-paracetamol combination BD for 3 days and post-operative instructions were given. In the next week, electrosurgery/surgical abrasion using diamond burs was performed on the other side [Figures 2 and 8]. To eliminate the demarcation between these two procedures, a mesial incision was given with BP blade.

Figure 3.

Patient 3 – Scalpel de-epithelization procedure (I quadrant)

Figure 4.

Patient 4 – A single sitting scalpel de-epithelization with frenectomy (upper arch)

Figure 6.

Patient 6 – Scalpel de-epithelization (I quadrant)

Figure 8.

Patient 6 – Outline of the incision using needle electrode

Electrosurgery

Needle electrode was used for incisions and ball electrodes of different diameters were used to coagulate [Figures 7–9]. Minimal bleeding with a clean field increased the efficacy of the work [Figures 9 and 10]. Light brushing strokes were used and the tip was kept moving all the time. Prolonged or repeated application of electrode to the tissues was avoided as it induces heat accumulation and causes undesired tissue destruction.[24] As it causes an undesired effect, enough care was taken to avoid contact of current with the periosteum and vital teeth, but at one point the tissue fenestrated [Figure 10].

Figure 9.

Patient 6 – Ball electrodes of different diameters used for coagulation

Figure 10.

Patient 6 – Arrow showing fenestration between the canine and the premolar region

RESULTS

Scalpel technique

No post-operative pain, hemorrhage, infection or scarring occurred. Although mild inflammation at the canine-premolar region [Figure 11] was observed in one case, healing was uneventful. Patient's acceptance of the procedure was good and results were excellent as perceived by the patient [Figure 12]. No repigmentation occurred for the initial 24 weeks [Figure 13, patient 2, I quadrant], and the patient is being monitored for longitudinal period for any repigmentation.

Figure 11.

Patient 6: 1 week post-treatment, mild inflammation in the caninepremolar region

Figure 12.

Patient 1: 8 weeks post-operative following scalpel de-epithelization (I quadrant)

Figure 13.

Post-treatment Patient 1 – 22 weeks post-operative (post-op) following scalpel technique (I quadrant) and 2 weeks post-op following diamond bur abrasion (II quadrant) Patient 2: 24 weeks post-op after scalpel de-epithelization (I quadrant) and 12 week post-op after bur abrasion (II quadrant) Patient 3: 22 weeks post-treatment after scalpel de-epithelization (I quadranat) Patient 4: 20 weeks post-operative after scalpel de-epithelization and frenectomy (upper arch) Patient 5: 2 weeks post-treatment after bur abrasion (I quadrant) Patient 6: As Figure 13

Surgical bur abrasion

The results were similar and comparable to the scalpel technique. Patients’ acceptance of the procedure was good and no repigmentation was reported till 12 weeks period [Figure 13, patient 2, II quadrant], and the patient is being monitored for a long term.

Electrosurgery

Mild post-operative burning and no post-operative hemorrhage and infection occurred. Patient's acceptance of the procedure was not as good as contralateral surgery and the results were not as promising. The patient kept saying that the previous procedure was better [Figure 14]. Although the patient is under observation for any scarring, a difference in the color and texture between the two procedures was apparent [Figure 14].

Figure 14.

Patient 6: 3week post-op after scalpel de-epithelization (I quadrant) and 12 days post-electrosurgery (II quadrant)

Although electrosurgery has advantages of minimal bleeding and a cleaner work field, it requires more expertise and caution. The results with the conventional split thickness scalpel technique are excellent and better than electrosurgery. This conclusion was also supported by the patients’ feedbacks.

DISCUSSION

To treat depigmentation and to enhance esthetics, numerous techniques have been employed from time to time. This review further compiles the advantages and disadvantages of each technique.

Various techniques

-

De-epithelization

Electrosurgery[24]

-

Cryosurgery[36]

-

Chemical agents

-

a.90% phenol and 95% alcohol[38]

-

b.Ascorbic acid

-

a.

-

Laser[39]

Although any of the above techniques may be employed for depigmentation, selection of a technique should be based on clinical expertise, patient's affordability and individual preferences. They should be performed cautiously, with care to protect adjacent tissue, because inappropriate technique/application may cause gingival recession, damage to the periosteum and bone and may cause pain, discomfort and delayed wound healing.[30]

De-epithelization

Scalpel[7,25,26]

The procedure essentially involves surgical removal of the gingival epithelium along with a layer of the underlying connective tissue under adequate local anesthesia and allowing the denuded connective tissue to heal by secondary intention. The new epithelium that forms is devoid of pigmentation.[25] Care must be taken to remove all remnants of the pigment layer (to avoid chances of recurrences) and it should be removed in thin sections to avoid exposing the underlying bone. Scalpel de-epithelization is relatively simple and effective, and most economical of all the other techniques available. It does not require any sophisticated armamentarium, is easy to perform and, most importantly, requires minimum time and effort.[44] Also, the healing period for scalpel wound is faster than other techniques. However, it might result in unpleasant hemorrhage during or after surgery. Hence, it is necessary to cover the lamina propria with periodontal dressing for 7–10 days.[26] It also has chances of infection or recurrence. Results reported are excellent.[45] This technique is highly recommended in the Indian subcontinent considering equipment constraints and patient affordability.[26]

Gingival abrasion technique using diamond bur[27,28]

The process of healing in this method is similar to the scalpel technique. It is also a comparatively simple, safe and non-aggressive method that can be easily performed and readily repeated, if necessary, to eradicate any residual repigmentation.[46] Also, these techniques do not require any sophisticated equipment and are hence economical. Pre- and post-surgical care is similar to that of the scalpel technique. However, extra care should be taken to control the speed and pressure of the handpiece bur so as not to cause unwanted abrasion or pitting of the tissue. Minimum pressure with feather light brushing strokes with copious saline irrigation should be used without holding the bur in one place to perceive excellent results.[47]

Gingivectomy[30,31]

Removing the gingival margin by gingivectomy or the entire attached gingiva by the “push back” procedure may also be used. However, these procedures are associated with alveolar bone loss, prolonged healing by secondary intention and excessive pain and discomfort caused by exposure and denudation of the underlying bone.[18]

Gingival depigmentation has been attempted by displacing the flap (push back technique) by Kon et al., who reported that melanocytes may lose their ability, transiently, to produce and transfer the pigment to the keratinocytes as observed after gingivectomy.

Gingivectomy with free gingival graft[32,33]

Tamizi and Taheri[32] replaced pigmented gingiva with unpigmented free gingival autografts in 10 patients. At least two areas in each patient were grafted; one with a full thickness flap and another with a partial thickness flap. They reported no evidence of repigmentation for 4.5 years post-operatively in areas that received a full thickness flap, and only one instance of repigmentation was observed 1 year post-operatively in a patient treated with a partial thickness flap. Although the results were favorable, this technique required the use of additional surgical sites with added discomfort, and healing was reported to be slow and painful. The amount of tissue available in the donor area was also limited. Moreover, the esthetic result was not always satisfactory due to color differences between the palatal tissues and the gingiva,[48] resulting in poor tissue color matching at the recipient site.[49] Furthermore, the presence of a demarcated line commonly observed around the graft in the recipient site may itself pose an esthetic problem.

Acellular dermal matrix allograft[34,35]

ADMA has been used to treat burn patients and patients with soft tissue defects.[50] It is acellular and non-immunogenic and healing occurs by repopulation and revascularization rather than granulation to limit scarring.[51] Novaes et al. reported the use of ADMA for elimination of the gingival pigmentation.[35] These studies demonstrated the efficacy of the ADMA, with the advantages of reduced surgical time (due to elimination of the surgical procedure for donor tissue), decreased post-operative complications, unlimited amount of graft material and a predictable and satisfactory esthetic result. However, it is expensive and requires clinical expertise.

Electrosurgery[24]

According to Oringer's “Exploding cell theory,”[52] it is predicted that electrical energy leads to the molecular disintegration of melanin cells of the operated and surrounding sites. Thus, electrosurgery has a strong influence in retarding migration of melanin cells.[52] However, electrosurgery requires more expertise than the techniques mentioned above. Prolonged or repeated application of current to the tissues induces heat accumulation and undesired tissue destruction.[24] Contact of current with the periosteum and vital teeth should be avoided.[42] Hence, it is to be used in light brushing strokes and the tip has to be kept moving.

Cryosurgery

Cryosurgery[36] is a method of tissue destruction by rapid freezing. The cytoplasm of the cells freezes, leading to denaturation of proteins and cell death. It does not require use of local anesthesia or periodontal dressing, is relatively painless and has shown excellent results lasting for several years.[23] The cryotherapy procedure requires a special container for storage of liquid nitrogen (LN), and dispensing is difficult as it is highly volatile (-190°C) and is difficult to maintain for 20–30 s of freezing application. Moreover, the depth of penetration is difficult to control and prolonged freezing may cause excessive tissue destruction. Also, the shelf-life of LN is not high for storage for long periods. It is also important to handle the liquid carefully as accidental contact can cause injury to the skin or other contact areas. Also, no literature on dispensing, shelf-life or proper usage directions is available.

The Dip-stick method utilizes a small cotton bud/swab dipped in LN, which can be applied on the pigmented area and maintained in contact for around 20–30 s as described by Tal et al.[37] However, the removal of pigments cannot be evaluated during the procedure as immediate clinical changes are not appreciable and hence may lead to multiple applications. It requires a separate sitting after about 5 days, during which the residual pigmentation, if any, may be removed. Thus, this procedure requires a minimum of two sittings. Moreover, it is followed by considerable swelling and accompanied by increased soft tissue destruction.[53] It is said that all parts of the freeze–thaw cycle can cause tissue injury and healing may be uneventful. As immediate clinical changes cannot be noticed, it is difficult to analyze the site of previous application and hence depth control is difficult. Also, the optimal duration of freezing is not known and prolonged freezing increases tissue destruction.[26] Tal et al.[37] did not observe repigmentation until 20 months after cryosurgical depigmentation.

An alternative to the Dip-stick method is the use of gas-expansion cryosurgical guns with special probes. But, this requires extensive sophisticated equipment. It works on the Joule-Thompson effect, i.e. the “change in temperature that accompanies expansion of a gas without production of work or transfer of heat. The cooling occurs because work must be done to overcome the attraction between the gas molecules as they move further apart.”

Chemical agents (chemoexfoliation)

It is a treatment method that destroys the epidermis and/or dermis using a chemical peeling agent. A variety of chemical peeling agents are available; phenols, salicylic acid, glycolic acid, trichloracetic acid, etc. These agents have been classified into four types: Very superficial, superficial, medium depth and deep, based on their penetration.

90% phenol and 95% alcohol[22]

Phenol penetrates the subepithelial connective tissue and causes necrosis or apoptosis of melanocytes. It result in incapacity of melanocytes to normally synthesize melanin.[54] Phenol does not seem to determine melanocyte destruction; rather, it compromises its activity. Hirschfeld reported a series with 20 cases that were treated for melanin pigmentation with the phenol–alcohol method.[55] It requires the area to be air-dried before application The phenol pellet is applied and maintained for 1 min and the area needs to be rinsed with 99% alcohol. Eighty-eight to 90% phenol rapidly coagulates the epidermis thus decreasing its mucosal penetration. Although application is easy and no anesthesia is required, care must be taken not to contact other tissues as it causes undue effects. Transient or definite hypopigmentation is a feature of phenol cauterizing. It can be repeated subsequently until satisfactory depigmentation is achieved.

Phenol de-epithelization may be accompanied with inflammation of keratinocytes.[56] Burning sensation for approximately 60 s, followed by a transient period and pain returning after 10 min, with a lesser intensity that lasts from minutes to hours, is known. Post-operative care should include delicate cleaning of the gingiva with saline and prescribed antibiotic regimen. Phenol may induce cardiac arrhythmia; hence, hydration before, during and after the peel is required. Cardiac monitoring is necessary, especially in patients with cardiac, liver or kidney disease (partially detoxified in the liver and excreted by the kidneys).

Lasers

Lasers[39] are named according to the material used for the lasing medium Nd/YAG (neodymium-yttrium-aluminum-garnet), CO2, argon and ruby. Lasers combine the advantages of rapid healing of the scalpel surgery and the minimal bleeding of electrosurgery. A one-step laser treatment is usually sufficient to eliminate the pigmented gingiva and does not require a periodontal dressing. Easy handling, short treatment line, hemostasis, sterilization effects and excellent coagulation (small vessels and lymphatics) are its known advantages. The treated area should be left exposed in the mouth. Few myofibroblasts present in the base of the wound cause minimal contraction and scarring, with little restriction in movement of the soft tissues.

However, laser surgery does have some disadvantages. Delayed type of inflammatory reaction may occur with mild post-operative discomfort lasting up to 1–2 weeks. Epithelial regeneration (re-epithelialize) is delayed (lack of wound contraction) as compared to conventional surgery. Moreover, expensive and sophisticated equipment makes the treatment very expensive.[40] Another disadvantage is loss of tactile feedback while using lasers. Nevertheless, in hyperplastic conditions, for bloodless incision, partial thickness dissections and for the removal of soft tissue grafts from the palate leaving a dry wound (avoiding any post-operative bleeding complications), use of lasers is recommended.

Growing esthetic concerns require patients to seek cosmetic treatment for their unsightly pigmented gingiva. Several treatment modalities have been suggested and presented in the literature, ranging from a simple slicing method to free gingival grafts or “push back” operation, in which the alveolar bone may be, exposed leading to bone loss, secondary healing, discomfort and pain. Although the scalpel technique results in rapid healing with a satisfactory esthetic result, its efficacy lasted for a variable duration of time, making this technique mainly a short-term solution. The potential risk of injuring the bone surface during rotary instrumentation may lead to incomplete removal of the basal layer. Also, the presence of epithelial rete-pegs that penetrate the connective tissue further complicate the elimination of the basal layer by bur abrasion. A free gingival graft usually requires an additional surgical site and a careful concern for color matching. Furthermore, the presence of a demarcated line around the graft at the recipient site may itself elicit an esthetic problem. These disadvantages of conventional techniques are avoided with newer technologies like electrosurgery, cryosurgery and lasers. But, there exist some complications with these techniques as well. An electrosurgical procedure requires clinical expertise, occupies a large space and is expensive. Cryosurgery requires a skillful management because of the complicated technique and sophisticated instruments involved. It also involves the various drawbacks of using LN. Chemical agents such as 90% phenol and 95% alcohol have been used in combination. However, these agents are quite harmful to the oral soft tissues. Lasers lead to post-operative discomforts, require a longer healing time, with high cost of instruments and expensive treatment charges, making it less popular compared with the other techniques.

Our cases described a split mouth comparison of three popular techniques: Scalpel, bur abrasion and electrosurgery. Although we found that electrosurgery increased the efficacy of our work, giving a cleaner and a neater work field, it required a lot of precision. The results obtained till 24 weeks post-treatment suggested excellent results with the scalpel technique compared with other techniques. In view of the advantages and disadvantages of the various techniques available, scalpel de-epithelization still serves to be the best treatment modality for depigmentation. However, a long-term follow-up is required to study repigmentation patterns and durability. Pigment recurrence has been documented in the literature, following the surgical procedure, within 24 days to as long as 8 years. Spontaneous repigmentation has been shown to occur and the mechanism suggested is that the melanocytes from the normal skin proliferate and migrate into the depigmented areas. Further research is required on repigmentation to study the factors affecting the rate and length of time required for recurrence of pigmentation. Research should also focus on finding a solution for preventing recurrence and, till then, repeated depigmentation should be done to eliminate the unsightly pigmented gingiva.

CONCLUSION

Gingival melanin pigmentations can occur as a consequence of local, systemic, environmental or genetic factors. To ensure treatment success, the potential causative or aggravating agent of the pigmentation should be identified and eliminated, if possible, before the surgical treatment. Various techniques are available with some advantages and some drawbacks. However, choice of the technique should be dependent on individual preference, clinical expertise and patient affordability. More data is required on comparative techniques to ensure the long-term predictability and success.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tal H, Oegiesser D, Tal M. Gingival depigmentation by Erbium: YAG laser: Clinical observations and patients responses. J Peroiodontol. 2003;74:1660–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.11.1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dummett CO. Oral pigmentation: First symposium of oral pigmentation. J Periodontol. 1960;31:356. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dummett CO, Barens G. Pigmentation of the oral tissues: A review of literature. J Periodontol. 1967;38:369–78. doi: 10.1902/jop.1967.38.5.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Page LR, Corio RL, Crawford BE, Giansanti JS, Weathers DR. The Oral melanotic macule. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1977;44:219–26. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(77)90272-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cicek Y. The normal and pathological pigmentation of oral mucous membrane: A review. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2003;4:76–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dummett CO. Overview of normal oral pigmentations. J Indiana Dent Assoc. 1980;59:13–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perlmutter S, Tal H. Repigmentation of the gingiva following surgical injury. J Periodontol. 1986;57:48–50. doi: 10.1902/jop.1986.57.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fry L, Almeyda JR. The incidence of buccal pigmentation in caucasoids and negroids in Britain. Br J Dermatol. 1968;80:244–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1968.tb11966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrett AW, Scully Human oral mucosal melanocytes: A review. J Oral Pathol Med. 1994;23:97–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1994.tb01095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schroeder HE. Melanin containing organelles in cells of the human gingival: I, Epithelial melanocytes. J Periodont Res. 1969;4:1–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1969.tb01940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szako G, Gerald SB, Pathak MA, Fitz Patrick TB. Racial differences in the fate of melanosomes in human epidermis. Nature. 1969;222:1081. doi: 10.1038/2221081a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esen E, Haytac MC, Oz IA, Erdogan O, Karsli ED. Gingival melanin pigmentation and its treatment with the CO2 laser. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;98:522–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trelles MA, Verkmysse KL, Segui JM, Udaeta A. Treatment of melanotic spots in the gingiva by argon laser. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51:759–61. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(10)80416-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dummet CO, Barens G. Oromucosal pigmentation: An updated literary review. J Periodontol. 1971;42:726–36. doi: 10.1902/jop.1971.42.11.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Araki S, Murata R, Ushio K, Sakai R. Dose response relationship between tobacco consumption and melanin pigmentation in the attached gingiva. Archs Enviro Hlth. 1983;138:375–9. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1983.10545823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hedin CA, Larsson A. The ultra structure of the gingival epithelium in smoker's melanosis. J Periodont Res. 1984;19:177–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1984.tb00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Regezi JA, Sciubba J. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co.; 1993. Oral Pathology, Clinical Pathologic Correlations; pp. 89–161. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co.; 1984. A Textbook of Oral Pathology; pp. 89–136. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Granstien RD, Sober AJ. Drug and heavy metal induced hyperpigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(81)70072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Savage NW, Barber MT, Adkins KF. Pigmentary changes in rat mucosa following anti-malarial therapy. J. Oral Pathol. 1986;15:468–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1986.tb00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dummett CO. A classification of oral pigmentation. Mil Med. 1962;127:839–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dummett CO, Sakumura JS, Barens G. The relationship of facial skin complexion to oral mucosa pigmentation and tooth color. J Prosthet Dent. 1980;43:392–6. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(80)90207-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tal H, Landsberg J, Koztovsky A. Cryosurgical depigmentation of the gingiva: A case report. J Clin Periodontol. 1987;14:614–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1987.tb01525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gnanasekhar JD, Al-Duwairi YS. Electrosurgery in dentistry. Quintessence Int. 1998;29:649–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roshna T, Nandakumar K. Anterior esthetic gingival depigmentation and crown lengthening: Report of a Case. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2005;6:139–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Almas K, Sadig W. Surgical treatment of melanin pigmented gingiva: An esthetic approach. Indian J Dent Res. 2002;13:70–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sameer AM. Management of gingival Hyperpigmentation by surgical abrasion: Report of three cases. Saudi Dent J. 2006;18:162–6. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pal TK, Kapoor KK, Parel CC, Mukharjee K. Gingival melanin pigmentation: A study on its removal for esthetics. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 1994;3:52–4. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prasad SS, Neeraj A, Reddy NR. Gingival depigmentation: A case report. People's J Sci Res. 2010;3:27–9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bergamaschi O, Kon S, Doine AI, Ruben MP. Melanin repigmentation after gingivectomy: A 5-year clinical and transmission electron microscopic study in humans. Int J Periodont Restorat Dent. 1993;13:85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dummett CO, Bolden TE. Postsurgical clinical Repigmentation of the gingiva. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1963;16:353–65. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tamizi M, Taheri M. Treatment of severe physiologic gingival pigmentation with free gingival autograft. Quintessence Int. 1996;27:555–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dello Russo NM. Esthetic use of a free gingival autograft to cover an amalgam tattoo: Report of case. J Am Dent Assoc. 1981;102:334–5. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1981.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pontes AE, Pontes CC, Souza SL, Novaes AB, Jr, Grisi MF, Taba M., Jr Evaluation of the efficacy of the acellular dermal matrix allograft with partial thickness flap in the elimination of gingival melanin pigmentation: A comparative clinical study with 12 months of follow-up. J Esthet Restorat Dent. 2006;18:135–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2006.00004_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arthur BN, Carla CP, Sergio LS, Marcio FM, Mario T., Jr The use of acellular dermal matrix allograft for the elimination of gingival melanin pigmentation: Case presentation with 2 years of follow-up. Pract Proc Aesthet Dent. 2002;14:619–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yeh CJ. Cryosurgical treatment of melanin-pigmented gingiva. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;86:660–3. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90199-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tal H, Landsberg J, Kozlovsky A. Cryosurgical depigmentation of the gingiva: A case report. J Clin Periodontol. 1987;14:614–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1987.tb01525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hasegawa A, Okagi H. Removing melagenous pigmentation using 90 percent phenol with 95 percent alcohol. Dent Outlook. 1973;42:673–6. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stabholz A, Zeltser R, Sela M, Peretz B, Moshonov J, Ziskind D, et al. The use of lasers in dentistry: Principles of operation and clinical applications. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2003;24:935–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Atsawasuwan P, Greethong K, Nimmanon V. Treatment of gingival hyperpigmentation for esthetic purposes by Nd:YAG laser: Report of 4 cases. J Periodontol. 2000;71:315–21. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.2.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yousuf A, Hossain M, Nakamura Y, Yamada Y, Kinoshita J, Matsumoto K. Removal of gingival melanin pigmentation with the semiconductor diode laser: A case report. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 2000;18:263–6. doi: 10.1089/clm.2000.18.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ozbayrak S, Dumlu A, Ercalik-Yalcinkaya S. Treatment of melanin-pigmented gingiva and oral mucosa by CO2 laser. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:14–5. doi: 10.1067/moe.2000.106396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trelles MA, Verkruysse W, Segui JM, Udaeta A. Treatment of melanotic spots in the gingiva by argon laser. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51:759–61. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(10)80416-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Humagain M, Nayak DG, Uppoor US. Gingival depigmentation: A case report with review of literature. Journal of Nepal Dental Association. 2009;10:53–6. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kanakamedala AK, Geetha A, Ramakrishna T, Emadi P. Management of gingival hyperpigmentation by the surgical scalpel technique: Report of three cases. J Clin Diag Res. 2010;4:2341–6. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Putter OH, Ouellet D, Putter A, Vilaboa D, Vilaboa B, Fernandez M. A non-traumatic technique for removing melanotic pigmentation lesions from the gingiva: Gingiabrasion. Dent Today. 1994;13:58–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deepak P, Sunil S, Mishra R, Sheshadri Treatment of gingival pigmentation: A case series. India J Dent Res. 2005;16:171–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.29901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shulman J. Clinical evaluation of an acellular dermal allograft for increasing the zone of attached gingiva. Pract Periodont Aesthet Dent. 1996;8:201–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fowler EB, Breault LG, Galvin BG. Enhancing physiologic pigmentation utilizing a free gingival graft. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. 2000;12:193–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lattari V, Jones LM, Varcelotti JR, Latenser BA, Sherman HF, Barrette RR. The use of a permanent dermal allograft in full- thickness burns of the hand and foot: A report of three cases. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1997;18:147–55. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199703000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tal H. Subgingival acellular dermal matrix allograft for the treatment of gingival recession: A case report. J Periodontol. 1999;70:1118–24. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.9.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oringer MJ. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co; 1975. Electrosurgery in Dentistry. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gage AA, Baust J. Mechanisms of tissue injury in cryosurgery. Cryobiology. 1998;37:171–86. doi: 10.1006/cryo.1998.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stuzin JM, Baker TJ, Gordon HL. Treatment of photoaging: Facial chemical peeling (phenol and trichloroacetic acid) and dermabrasion. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:9–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hirschfeld I, Hirschfeld L. Oral pigmentation and a method of removing it. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1951;4:1012–6. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(51)90448-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yamamoto Y, Yonei N, Kamikawa C, Kishioka A, Furukawa F. Effect of chemical peeling on dental epithelial cells. J Dermatol Sci. 2004;35:158–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]