Abstract

Esthetic demands in today's world of dentistry are scaling new heights, and are driven by the zest to look beautiful. The soft tissue esthetics around implants is the foci of attention, which, if failed to meet, leads to unacceptable esthetic failure. The aim of this article is to give a brief overview of the various vital parameters influencing the esthetics governing the peri-implant area.

Keywords: Peri-implant esthetics, soft tissue esthetics, peri-implant soft tissue, anterior implant esthetics

INTRODUCTION

The common esthetic factor in today's world of implant dentistry talks about the soft tissue profile. During the advent of the Branemark system, the esthetic requirement was not taken into consideration for many years. Palacci was the first clinician to consider the esthetic problem in relation to the peri-implant zone in the anterior region of the mouth.[1] Today's world of implantology not only talks about the appealing prosthetic restorative options but also esthetics that are identical to the contralateral natural healthy teeth and the gingival outline harmonious with the gingival silhouette of the adjacent teeth.

The peri-implant zone primarily comprises of the crestal bone and the healthy soft tissue around it. They are considered necessary for the long-term success of implant-supported restorations. If these two parameters are respected, implant therapy can be a reliable treatment with an impressive outcome.[2] The primary function of a soft tissue barrier at implants is to effectively protect the underlying bone and prevent ingress of microorganisms and their products. Rationale for the peri-implant soft tissue is: It acts as a transmucosal seal, it resists recession with predictability and enhances an ideal esthetic blending, provides a prosthetic-friendly environment to withstand the mechanical challenge and provides appropriate contours that facilitate a self-cleansing environment.

TOOTH VERSUS IMPLANT : THE BIOLOGIC DIFFERENCES

The peri-implant esthetics is primarily contributed by the dental papilla and the adjoining marginal gingiva. The peri-implant papilla primarily is the anatomical entity that houses beneath the contact point of the natural tooth and an implant or two adjacent implants. The mucosa that encircles the implant has more of collagen and fewer fibroblasts as opposed to gingival tissues. The collagen fiber bundles run parallel to the titanium surface without attaching to it versus the perpendicular direction around the tooth.[3] Poor vascular supply is present in the peri-implant tissues than in the natural teeth. Location of the biologic width is yet another significant difference between them. The implant has the biologic width positioned subcrestally as apposed to the supracrestal formation around the tooth. This subcrestal formation of biologic width results in loss of the interproximal bone. Lack of cementum around the implant has collagen fibers arranged parallel to the tooth surface vs. the perpendicular arrangement around the tooth. Peri-implant tissues are similar to the periodontium, with a junctional epithelium containing basal lamina and hemidesmosomes and connective tissue fibers.

FACTORS GOVERNING THE PERI - IMPLANT ESTHETICS

Factors governing the peri-implant esthetics are the peri-implant marginal bone and the peri-implant papilla.

The peri-implant marginal bone

The peri-implant marginal bone is governed by the following parameters: Biologic width, the concept of platform switching, implant design in the cervical region, thread geometry, insertion depth and the microlesions produced by the second-stage prosthetic intervention.[4] A stable bone level around the implant neck is a prerequisite for achieving the support and hence long-term optimal and stable gingival contour.

Biologic width

The term biologic width denotes the dimensions of the periodontal and peri-implant tissues, which comprise of: Gingival sulcus, junctional epithelium and supracrestal connective tissue. The dimension of the peri-implant mucosa has been demonstrated to resemble that of the gingiva at teeth and included a 2-mm-long epithelial portion and a connective tissue portion about 1–1.5 mm long.[5] The entire contact length between the implant and the epithelial and the connective tissue portions is defined as “the biological width.” Experimental studies have demonstrated that a minimum width of the peri-implant mucosa was required. If the thickness of the peri-implant mucosa was reduced, bone resorption occurred to re-establish the mucosal dimension that was required for protection of the underlying tissues.[6] The long-term preservation of the healthy peri-implant tissues is of primary importance for ensuring the function and esthetics.

Numerous studies have revealed that the bone resorption around the implant neck does not start until the implant neck is uncovered and exposed to the oral cavity, which leads to bacterial contamination of the gap between the implant and the super structure.[7–10] This eventually leads to the bone remodeling that follows till the biologic width has been created. Tarnow[7,11] had stated that apart from the vertical component of re-establishing this width, there exists a horizontal component approximating 1–1.5 mm that maintains the health of the interproximal bone and, in turn, the papilla.

The platform switch concept

The abutments used with the conventional conventional type of implants usually flush with the implant shoulder in the contact zone. There exists a microgap between the contact point at the implant abutment junction (IAJ) that has shown bacterial contamination, which affects the peri-implant crestal bone health by leading to crestal bone loss.[8,9,11–13] This bone loss may lead to vertical and horizontal crestal bone loss. This entire process is actually a sequel of the bacterial infection occurring as a result of the communication that occurs when the IAJ is exposed to the oral cavity.[10] A serendipitous finding came in the early 1990s when major implant companies were a serendiptous finding in the early 1990’, revealed that major implant companies were using the narrow diameter abutments on the wider diameter implants, as the congruent abutments were not available using narrow diameter abutments on the wide diameter implant, as the congruent abutments were not available. Long-term radiographic follow-up of these shifted diameters demonstrated a smaller than expected vertical change in the crestal bone height around these implants than is typically observed around implants restored conventionally with prosthetic components of matching diameter. This radiographic observation suggested that the resulting post-restorative biologic process resulting in the loss of the crestal bone height is reduced when the outer edge of the implant abutment interface is horizontally repositioned inwardly and away from the outer edge of the implant platform. This lead to the laying down of the concept of “platform switching.” This concept requires that the microgap be placed away from the implant shoulder and closer toward the axis thus mesializing the inflammatory zone away from the crestal bone.

Implant neck geometry, size of microgap

The implant neck design is one of the areas of development to improve the integrity of the soft tissue integration. Microtextured and macrotextured surfaces have been explored in this context. These designs mainly aimed to enhance the stability of interface for both soft and hard tissue and minimize the marginal bone reduction in the first year of implantation. Proposed levels of crestal bone loss as reported in the literature[14] were countered by the recent human clinical trial of the laser-microtextured implant surface by Pecora et al.[15] In the 3-year post-operative results, it was reported that the laserlock surface treatment enables the reduction of the crestal bone loss to 0.59 mm. Possible reasons are attributed to the reduction of the crestal bone stress through a combination of the implant design and surface modification. Size of the microgap between the implant and the abutment has little influence on marginal bone remodeling, whereas the micromovements of the abutments induce significant bone loss independent of the size of the microgaps.[12]

Abutment disconnection and microlesion

Micromovements associated with the replacement of secondary components (violation of the biologic width) at the time of insertion of the prosthetic superstructure results in apical migration of the epithelial tissue around the implant neck leading to bone resorption and reduction of the marginal bone level.[16] A good connective tissue integration to the titanium surface at the IAJ prevents the apical proliferation of the epithelial tissue, but if this is disturbed by plaque accumulations/exchange of secondary components (healing caps/impression posts), this apical proliferation then reflects the risk on the crestal bone.

The peri-implant papilla

This anatomic entity lies underneath the contact point between a natural tooth and an implant or two adjacent implants. Factors influencing the papilla integrity are: Crestal bone height, interproximal distance, tooth form and shape, gingival thickness and gingival biotype.

Crestal bone height

Several studies have recognized the underlying osseous morphology as the key component for the foundation and support of the gingival tissue.[17–19] Tarnow in his classic study has demonstrated the effects of the crestal bone height on the presence or absence of the dental papilla. The results revealed that when the distance from the contact point to the crest of the bone is 5 mm or less, the papilla fill is almost 100%[20] as compared with the single dental implant; the regeneration of the papilla is further difficult and challenging between the two adjacent implants. Studies have revealed that the ideal distance from the base of the contact point to the bone crest between adjacent implants is 3 mm and between the tooth and the implant is <5 mm.[21]

Interproximal distance

Tarnow in his study revealed that a minimum of 3 mm of the interimplant distance is important to have a healthy crestal bone in between.[20] The interproximal distance affects the appearance of the hard and soft tissues. Inter-root distance when <0.5 mm results in a thin lamina dura and when 0.3 mm, the crestal bone disappears and the adjacent root surfaces are connected to each other with periodontal ligament.[21,22] This ultimately leads to the disappearance of the papilla. Cho et al. found that the ideal vertical and horizontal distance between two roots should be 5 mm and 1.5–2.5 mm, respectively.[23]

Tooth form and shape

In natural dentition, gingival morphology is partly related to the tooth shape and form. Tooth shape is classified into triangular, ovoid and square and the tooth form as long narrow and short wide. Olson and Lindhe[24] in their study reported that the individuals with long narrow tooth form demonstrated a thin free gingiva, shallow probing depth and pronounced scalloped contour of the gingival margin. Similarly, the tooth shape and form can influence the peri-implant soft tissue architecture. Tooth shape is one of the five essential diagnostic key factors for the peri-implant esthetics.[25,26] Individuals with square-shaped teeth have more favorable esthetic outcomes because of the long proximal contact and less of the papillary tissue, whereas the triangular tooth shape has a proximal contact located more incisally and needs more tissue height to fill in and hence is at a high risk of the “black hole disease.”

Gingival biotype

It is an essential element for the peri-implant esthetics. Two biotypes have been proposed: Thin scalloped and flat thick.[23,25,26] Thin biotype has a deficient underlying osseous support and poor vascularization, and the surgical response results in increased facial recessions and loss of the interproximal tissue. On the contrary, the thick tissue has a thick underlying osseous support with accompanying good vascular supply and is resistant to physical damage and bacterial ingress.

Tooth position, type of gingival scallop, amount of keratinized tissue

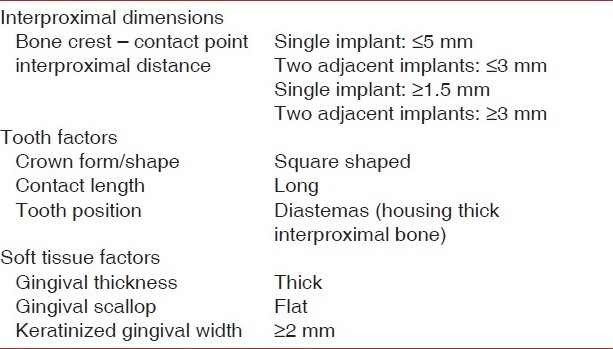

Before extraction of the hopeless tooth, it is important to determine the position of the tooth in relation to the adjacent dentition as it influences the gingival architecture. Root proximity with thin interdental bone is more vulnerable to the resorptive process, leading to the soft tissue loss, in contrast to the tooth with wide interproximal bone. Gingival scallop can be high, normal or flat.[18] As compared with the normal or high gingival scallop, the flat gingival architecture has less tissue coronal to the bone interproximally than facially. It tends to follow the osseous scallop and hence has a less risk of interproximal tissue loss post-extraction and therefore a predictable papilla. Role of the keratinized/attached gingiva around the tooth or peri-implant tissue has been a topic of debate.[27] Consensus states that good oral hygiene maintenance with less of the keratinized tissue does not increase the incidence of the attachment loss or soft tissue recession. However, predictable manipulation of the soft tissue surrounding the peri-implant tissues and the long-term success of the endosseous implant demands the availability of a keratinized mucosa [Table 1].Table 1depicts the favourable conditions for the peri-implant papilla

Table 1.

PERI-IMPLANT ESTHETICS: THE PRACTICAL APPROACH

Pre-surgical approach

Management of the implants in the esthetic zone demands excellent planning and treatment skills. Preservation of the available hard and soft tissue structure is far more important than reconstructing the same. Important parameters of the pre-surgical concern are: Implant size selection, implant positioning, emergence profile, hard and soft tissue management in implant-deficient sites, periodontal biotype and soft tissue quality and quantity.[28]

Pre-surgical assessment

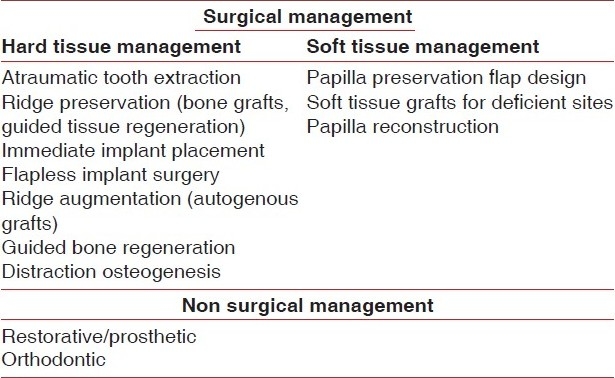

The esthetic quality of the implant restoration chiefly depends on the morphology of the edentulous crest and the accompanying bone volume (height and thickness). Bone volume can be ascertained prior either by palpation and visual analysis, computed topography or bone mapping.[29,30] Pre-operative assessment of the requirement of the soft tissue augmentation should be evaluated whether to be done before/during/after implant placement. Surgical and non-surgical techniques have evolved in the management of the hard and soft tissues [Table 2].

Table 2.

Surgical management

Ideal implant selection in terms of the size and position is the key when planning for the esthetic zone, and this depends on the dimensions of the edentulous crest and the proximity of the adjacent roots. Three-dimensional placement of the implant is the ideal way to place the implant, i.e. taking into consideration the apicocoronal, mesiodistal and buccolingual directions.

Hard tissue management becomes an essential component in implant dentistry. Crestal bone resorption after tooth extraction not only compromises ideal implant placement but also leads to unacceptable esthetic outcomes. Controlling and preserving the hard tissue height helps achieve a sound peri-implant margin and interproximal papilla. Ridge deficiencies can be enhanced by guided bone regeneration, autogenous ridge augmentation and distraction osteogenesis.[32,33] Ridge preservation is a predictable method to maintain the ridge height, width and position. Hence, atraumatic extraction of the tooth with the aim of maintaining the patency of the socket space with bone substitute and membrane should be done. Immediate implant placement is yet another method of allowing preservation of the alveoli and the surrounding structures with esthetic outcomes. A 100% success rate has been reported after 1-year follow-up after immediate implant placement.[41] Flapless placement of implants have shown their added advantage over conventional procedures as lessened surgical time, less bleeding and decreased post-operative discomfort and minimal crestal bone loss, soft tissue inflammation and probing depth adjacent to the implants.[34]

Soft tissue management is one of the many factors that have a considerable impact on the esthetic results in relation to the color, form and contour with that of the adjacent tissues. Soft tissue intervention can either be carried out before, at the time, after implant placement or post-abutment connection.[28] Management involves optimizing the peri-implant status by conditioning the soft tissues around the failing root to receive the implant, esthetic incisions and flap designs innovative soft tissue closure techniques, augmenting the deficient sites with inlay, onlay and vascularised interpositioned periosteal connective tissue graft (VIP-CT grafts). The concept of the in situ augmentation aims grinding the remnant root piece below the crestal bone level and allowing adequate keratinized tissue to grow in height, preventing post-extraction bone loss, stabilizing the mucogingival junction at the biologic level.[42] Soft tissue-deficit sites can either be augmented with onlay and inlay connective tissue grafting or with VIP-CT grafts that has the add-on benefit of augmenting volume defects, excellent vascular supply and minimum post-operative shrinkage.[43] Plastic and reconstructive surgery principles have been incorporated in implantology with the inclusion of the curvilinear bevelled incisions with added benefits of improved elasticity in the flaps, good coaptation of the flaps and minimum or negligible post-operative healing scar.[43] Flap designs with papilla-sparing incisions protect the underlying bone and in turn the interproximal papilla against the post-operative recession.[41] Several techniques evolved over the years to reconstruct the deficient papilla with the traditional methods using the connective tissue graft.[44] Palacci developed a novel papilla regeneration technique at the stage two uncovery of the implant with a semilunar beveled incision in relation to the elevated flap in relation to each implant to create a pedicle that is rotated at 90 degrees to the mesial aspect of the abutment and stabilized with the interrupted mattress suture to form new interimplant papilla.[36] Several modifications of Palacci's technique have been reported. Misch et al. used the “split finger technique” to promote papilla formation.[45]

Non-surgical management

Restorative/prosthetic techniques

Certain prosthetic/restorative techniques may be helpful for treating the papillary insufficiency to achieve esthetic outcomes. By means of restorative/prosthetic reshaping, the contact of the crowns can be lengthened and located more apically. The resulting effects lead to the illusion of the papilla regeneration.[46] Ovate pontic helps in molding the papillary height and the gingival embrasure form.[39] Jemt et al. attempted at promoting the interimplant papillary formation by means of placing a provisional resin crown at the time of the second-stage surgery. The provisional crown guides the interimplant soft tissue space.[37]

Orthodontic therapy

Excellent esthetic outcomes can be brought out with orthodontic intervention. Forced orthodontic extrusion is considered to enhance both the hard and the soft tissue profiles in teeth and roots indicated for extraction. Sites with diastema have missing interdental papilla, and orthodontic tooth approximation with apical positioning of the contact point through stripping gives appropriate remedy to such situations.[38] Root divergence and the accompanying open embrasure space can recreate the new papilla by orthodontic realigning of the roots and squeezing the interproximal tissues.[39] In a novel approach, autologous fibroblast injections have been tried in the deficient papillary areas with convincing results, but tissue stability was a concern over time. However, future research is needed in this area.[47]

Soft tissue stability

Studies supporting the stability of the soft tissue over time 12 months–10 years[48] have revealed a probing depth of 0.24 mm around implants to 0.27 mm around teeth.[48,40] Clinical attachment levels varied from 0.37 mm around implant vs. 0.3 mm around teeth. A landmark study by Bengazi et al.[40] has observed 0.4 mm of gingival recession at 6 months at the augmented site vs. 0.7 mm at the non-augmented sites during the 24 months follow-up. Grunder[49] reported 0.6 mm shrinkage of the augmented soft tissue margin after prosthetic insertion. The possible reasons attributed to the dimensional changes observed are: Recession of the peri-implant soft tissue margin may be due to remodeling of the soft tissue to establish the biodimensions, bulking of the keratinized mucosa at the second-stage surgery compensates the future soft tissue shrinkage and improves the overall tissue profile, provisional prosthesis to be placed for 6 months after the abutment connection until a stable gingival margin is obtained, complete maturation of the tissues following second-stage surgery allows the tissue to be resistant to prosthetic manipulations and possible gingival recessions.

THE PRACTICAL LIMITATIONS OF THE PERI - IMPLANT PAPILLA RECONSTRUCTION

The highlighting anatomical and the histologic differences between the peridental and the peri-implant papilla apparently project the biggest limitation in the predictable reconstruction of the peri-implant papilla. The restricted blood supply and a high collagen and low cellular level define the peri-implant mucosa as a “scar-like tissue” hence reducing the reconstructive predictability of the papilla.[44] The anatomical location of the biologic width in relation to two adjacent teeth is supracrestal. This anatomical entity and its relationship with the IAJ is subcrestal when formed between implant and adjacent teeth and between two adjacent implants. This subcrestal location leads to crestal bone loss at the interface, more between the two adjacent implants (microgap).[50] The crestal height (vertical distance from the contact point to the alveolar crest), interproximal dimensions between the adjacent implants/the tooth and implant are the crucial parameters that govern the predictability of the peri-implant papilla construction.[20,21,51]

CONCLUSIONS

An increased cosmetic demand from the patient and profession requires further emphasis on the gingival esthetics and compromised results are possibly considered as esthetic failure. The major issue of concern governs the stability of the augmented tissues over a period of time. Long-term clinical controlled trials are desired in this area to evaluate this grey area in terms of stabilization.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pallacci P. Peri-implant soft tissue management: Papilla regeneration technique. In: Palacci P, Ericcsson I, Engstrand P, Rangert B, editors. Optimal Implant Positioning and soft tissue management for the Branemark System. Chicago: Quintessence; 1995. pp. 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lekholm U, Gunne J, Henry P, Higuchi K, Lindén U, Bergström C, et al. Survival of the Branemark implants in partially edentulous jaws: A 10 year prospective multicenter study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1999;14:639–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berglundh T, Lindhe J. Soft tissue barrier at implants and teeth. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1991;2:81–90. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1991.020206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hermann F, Henriette L, Palti A. Factors influencing the preservation of the peri-implant marginal bone. Implant Dent. 2007;11:162–9. doi: 10.1097/ID.0b013e318065aa81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berglundh T, Lindhe J. The topography of the vascular system in the periodontal and peri-implant tissues. J Clin Periodontol. 1994;21:189–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1994.tb00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berglundh T, Lindhe J. Dimensions of the peri-implant mucosa.Biologic width revisited. J Clin Periodontol. 1961;32:261–7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quireynen M, Bollen CM. Microbial penetration along the implant components of the Branemark system: An in vitro study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1994;5:239–44. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1994.050407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Person LG, Lekholm U. Bacterial colonization on internal surfaces of the Branemark system implant components. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1996;7:90–5. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1996.070201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dibart S, Warbington M, Su MF. In vitro evaluation of the implant-abutment bacterial seal: The locking taper system. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;20:732–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quireynen M, Van Steenberghe. Bacterial colonization of the internal part of the two stage implants: In vivo study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1993;4:158–61. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1993.040307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tarnow DP, Cho SC, Wallace SS. The effect of the interimplant distance on the height of the interimplant bone crest. J Periodontol. 2000;71:546–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.4.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hermann JS, Schoolfield JD, Schenk RK, Buser D. Influence of the size of the microgap on crestal bone changes around titanium implants: A histometric evaluation of unloaded non-submerged implants in the canine mandible. J Periodontol. 2001;72:1372–83. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.10.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Todescan FF, Pustiglioni FE. Influence of the microgap in the peri-implant hard and soft tissues: A histomorphometric study in dogs. Intl J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2002;17:467–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ricci JL, Charvet J, Freknel SR. Bone response to laser microtextured surfaces. In: Davies JE, editor. Bone Engineering. 2000. Chapter 25. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pecora G, Ricci J. Clinical evaluation of laser microtexturing for soft tissue and bone attachment to dental implants. Implant Dent. 2009;18:57–66. doi: 10.1097/ID.0b013e31818c5a6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abrahamson I, Berglundh T, Lindhe J. the mucosal barrier following abutment connection and disconnection: An experimental study in dogs. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:569–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chow Y, Wang HL. Factors and techniques influencing the peri-implant papilla. Implant Dent. 2010;19:208–19. doi: 10.1097/ID.0b013e3181d43bd6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kois JC. Altering gingival levels: The restorative connection part 1: Biologic Variables. J Esthet Dent. 1994;6:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Becker W, Ochsenbein C, Tibbetts L, Becker BE. Alveolar bone profiles as measured from dry skulls: Clinical ramifications. J Clin Periodontol. 1977;24:727. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tarnow D, Fletcher P. Effect of the distance from the contact point to the crest of the bone on the presence or absence of the interproximal dental papilla. J Periodontol. 1992;63:995–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.12.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tarnow DP, Wallace SS. The effect of the interimplant distance on the height of the interimplant bone crest. J Periodontol. 2000;71:546–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.4.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heins PJ, Weider SM. A histologic study of the width and nature of interradicular space in human adult premolars and molars. J Dent Res. 1986;65:948–51. doi: 10.1177/00220345860650061901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho HS, Jang HS. The effects of the interproximal distance between roots on the existence of the interdental papilla according to the distance from the contact point to the alveolar crest. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1651–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.060023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olsen M, Lindhe J. Periodontal characteristics in individuals with varying form of the upper central incisor. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18:78–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1991.tb01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kois JC. Predictable single tooth peri-implant esthetics: Five diagnostic keys. Compend Contin Edu. 2001;22:199–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garber DA, Salama MA. Immediate tooth replacement. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2001;22:210–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strub J, Gaberthuel T. The role of attached gingival I the health of the peri-implant tissue in dog. Intl J Periodont Restorat Dent. 1992;12:415–25. [Google Scholar]

- 28.El Askary AS. Multifaceted aspects of implant esthetics: The anterior maxilla. Implant Dent. 2001;10:182–91. doi: 10.1097/00008505-200107000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinberg LA. CT scan as a radiologic database for optimum implant orientation. J Prosthet Dent. 1993;69:381–5. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(93)90185-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boudrias P. Evaluation of the osseous edentulous ridge (ridge mapping): Probing technique using a measuring guide. J Dent Que. 2003;40:301–2. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lang NP. The relationship between the width of the kertinized gingival and the gingival health. J Periodontol. 1972;43:623–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.1972.43.10.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kay SA, Wisner-Lynch L. Guided bone regeneration: Integration of a resorbable membrane and a bone graft material. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. 1997;9:185–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lehrhaupt NB. Alveolar distraction: A possible new alternative to bone grafting. Int J Periodont Restorat Dent. 2001;21:121–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oh TJ, Shotwell JL. Effect of flapless implant surgery on soft tissue profile: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2006;77:874–82. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gomez-Roman G. Influence of the flap design on the peri-implant interproximal crestal bone loss around the single tooth implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2001;16:61–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palacci P. Chicago: Quintessence Int; 1995. Perio-implant soft tissue management: Papilla regeneration technique. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jemt T. Restoring the gingival contour by means of provisional resin crowns after single tooth implantation. Int J Periodont Restorat Dent. 1999;19:20–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ingber JS. Forced eruption: Alteration of soft tissue cosmetic deformities. Int J Periodont Restorat Dent. 1989;9:416–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carnio J. Surgical reconstruction of the interdental papilla with connective tissue graft. Int J Periodont Restorat Dent. 2004;24:31–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bengazi F, Wennström JL, Lekholm U. Recession of the soft tissue margin at oral implants: A 2- year longitudinal prospective study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1996;7:303–10. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1996.070401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Juodzbalys G, Wang HL. Soft and hard tissue assessment of immediate implant placement: A case series. Clin Oral Implant Res. 2007;18:237–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2006.01312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Langer B. Spontaneous in situ gingival augmentation. Intl J Periodont Restorat Dent. 1994;14:524–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.S clar AG. Chicago: Quintessence Int; 2003. Soft tissue and esthetic considerations in implant therapy; pp. 483–99. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pradeep AR, Karthikeyan BV. Peri-implant papilla reconstruction: Realities and limitation. J Periodontol. 2006;77:534–44. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Misch CE, Al-Shammari KF, Wang HL. Creation of interimplant papilla through a split finger technique. Implant Dent. 2004;13:20–7. doi: 10.1097/01.id.0000116368.76369.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blatz MB. Reconstruction of the lost interproximal papilla: Presentation of the surgical and nonsurgical approaches. Int J Periodont Restorat Dent. 1999;19:395–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McGuire MK, Scheyer ET. A randomized double blind placebo controlled study to determine the safety and efficacy of the cultured and expanded autologous fibroblast injections for the treatment of the interdental papillary insufficiency associated with the papilla priming procedure. J Periodontol. 2007;78:4–17. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karoussis IK, Muller S. Association between periodontal and peri-implant conditions: A 10-year prospective study. Clin Oral Implant Res. 2004;15:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2004.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grunder U. Stability of the mucosal topography around singletooth implants and adjacent teeth: 1-Year Results. Quintessence Int. 2000;17:11–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cochran DL. Biologic width around titanium implants: A histometric analysis of the impantogingival junction around unloaded and loaded nonsubmerged implants in the canine mandible. J Periodontol. 1997;68:186–98. doi: 10.1902/jop.1997.68.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gastaldo JF, Cury PR. Effect of the vertical and the horizontal distances between adjacent implants and between the tooth and the implant on the incidence of the interproximal papilla. J Periodontol. 2004;75:1242–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.9.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]