Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES:

Human metapneumovirus (hMPV) and the Netherlands human coronavirus (HCoV-NL63) have been isolated from children with respiratory tract infection. The prevalence of these viruses has not been reported from Saudi Arabia. We sought to determine whether hMPV and HCoV-NL63 are responsible for acute respiratory illness and also to determine clinical features and severity of illness in the hospitalized pediatric patient population.

DESIGN AND SETTING:

Prospective hospital-based study from July 2007 to November 2008.

PATIENTS AND METHODS:

Nasopharyngeal specimens from children less than 16 years old who were suffering from acute respiratory diseases were tested for hMPV and HCoV-NL63 by reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction. Samples were collected from July 2007 to November 2008.

RESULTS:

Both viruses were found among Saudi children with upper and lower respiratory tract diseases during the autumn and winter of 2007 and 2008, contributing to 11.1% of all viral diagnoses, with individual incidences of 8.3% (hMPV) and 2.8% (HCoV-NL63) among 489 specimens. Initial symptoms included fever, cough, and nasal congestion. Lower respiratory tract disease occurs in immunocompromised individuals and those with underlying conditions. Clinical findings of respiratory failure and culture-negative shock were established in 7 children infected with hMPV and having hematologic malignancies, myelofibrosis, Gaucher disease, and congenital immunodeficiency; 2 of the 7 patients died with acute respiratory failure. All children infected with HCoV-NL63 had underlying conditions; 1 of the 4 patients developed respiratory failure.

CONCLUSION:

hMPV and HCoV-NL63 are important causes of acute respiratory illness among hospitalized Saudi children. hMPV infection in the lower respiratory tract is associated with morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised children. HCoV-NL63 may cause severe lower respiratory disease with underlying conditions.

Human metapneumovirus (hMPV) is a newly identified member of the family of Paramyxoviridae. hMPV infections have been identified worldwide and have been shown to be the cause of both upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) and lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) in infants and young children, as well as the elderly. Severe and fatal hMPV infections have been reported in immunocompromised patients.

Human coronaviruses (HCoVs) are recognized as one of the most frequent causes of common colds and URTI, after rhinoviruses. Until recently, HCoV-229E and HCoV-OC43 were known to infect humans. HCoV-NL63 was identified in 2004 and is often associated with mild URTI, although severe LRTI has also been observed.

The prevalence of hMPV and HCoV-NL63 has not been reported from Saudi Arabia. To investigate the role of hMPV and HCoV-NL63 in acute respiratory infection in hospitalized Saudi children, we applied molecular biology techniques to identify these two viruses in respiratory specimens submitted to the clinical virology laboratory at King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre (KFSHRC) in Riyadh over the course of 16 months.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We performed prospective molecular testing for hMPV and HCoV-NL63 on all respiratory specimens (predominantly nasopharyngeal aspirates [NPAs] [99.2%] but also included bronchioalveolar lavage [BAL] [0.8%]) obtained from children ≤16 years of age who were admitted with acute respiratory disease between July 2007 and November 2008 at KFSHRC in Riyadh. hMPV and HCoV-NL63 are difficult to cultivate in tissue culture. For this reason, molecular biology techniques were used. A database, including patient identifying member, age, gender, date of specimen collection, clinical manifestations, underlying conditions, and outcome of patients, was established. Molecular testing for respiratory viruses is part of the routine virological assays in our hospital's clinical virology laboratory.

Respiratory specimens were centrifuged, and supernatants were analyzed for hMPV and HCoV-NL63 by Seeplex respiratory virus detection kit from Seegene. RNA was purified by use of QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN). Specimens were tested for hMPV and HCoV-NL63 by use of Seeplex system, which applies dual specific oligonucleotide (DPO) technology, which produce greatly improve specificity without any false-positive. DPO contains two separate priming regions joined by polydeoxyinosine linker. The linker assumes a bubble-like structure, which itself is not involved in priming but rather delineates the boundary between the two parts of the primer. This structure results in two primer segments with distinct annealing properties: a longer 5’-segment that initiates stable priming and a short 3’-segment that determines target-specific extension. This DPO-based system is a fundamental tool that blocks extension of nonspecifically primed templates, thereby generating consistently high polymerase chain reaction (PCR) specificity, even under less-than-optimal PCR conditions. An internal control was included to check for any problem ocurring during PCR. The hMPV and HCoV-NL63 genes did not cross-react with influenza A and B viruses; respiratory syncytial virus (RSV); parainfluenza viruses (PIVs) PIV1, PIV2, PIV3; rhinovirus A; or adenovirus. Positive reverse transcriptase–PCR for hMPV and HCoV-NL63, respectively, was rigorously verified by the Mayo Clinic Laboratory (United States). The clinical data were analyzed and were expressed as percentages where applicable.

RESULTS

We identified 144 respiratory viruses in the 489 respiratory samples tested during the study period and detected the presence of hMPV and HCoV-NL63 in 16 (11.1%) of the 144 samples, hMPV in 12 (8.3%), and HCoV-NL63 in 4 (2.8%) samples.

Epidemiological characteristics of hMPV and HCoV-NL63

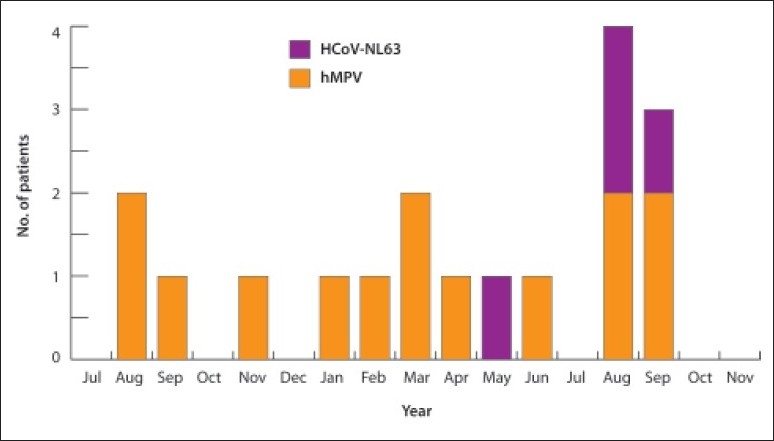

hMPV showed broad seasonal activity. The peak incidence was in March, August and September. HCoV-NL63 infection were noted in March, September and peaked in August (Figure 1). The age distribution with regard to hMPV and HCoV-NL63 infections differed. A greater proportion of hMPV infection compared with HCoV-NL63 infection occurred in children between the ages of 1 and 4 years. All cases of HCoV-NL63 were identified in children less than 2 years of age. The male-to-female ratio among children with hMPV infection and HCoV-NL63 infection, respectively, was 2:1.

Figure 1.

Monthly distribution showed infections with hMPV and HCoV-NL63.

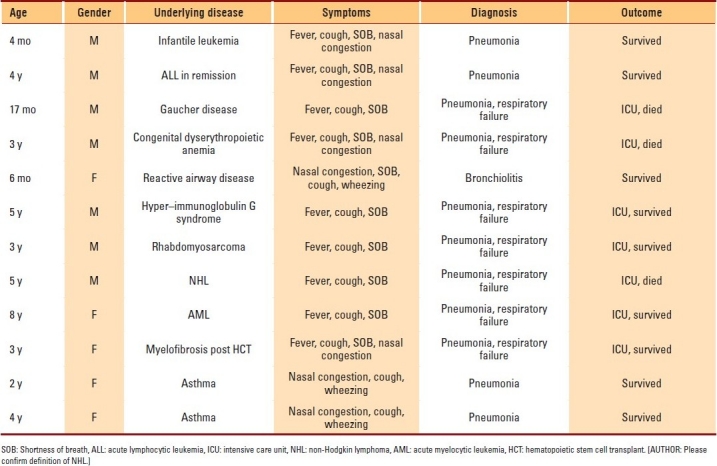

Clinical characteristics of hMPV infections

Clinical characteristics of hMPV infections are listed in Table 1. Ten (83%) hMPV-positive children had serious underlying medical conditions. The most frequent reported conditions were hematologic malignancies and related disorders (6), malignant neoplasm (1), congenital immunodeficiency (1), metabolic disease (1), and Guillain-Barré syndrome (1). Clinical signs and symptoms at disease onset included cough in 12 (100%) children, shortness of breath in 10 (86%), fever in 9 (75%), nasal congestion in 8 (66%), and wheezing in 3 (25%) children . Because of the severity of the infection, 7 (58%) patients required admission to the intensive care unit; all had underlying medical conditions. Among the 8 children with hematological malignancies and related disorders, 7 (86%) were admitted to the intensive care unit with pneumonia, respiratory failure, and culture-negative shock with radiological evidence of diffuse pulmonary disease. Mixed viral infections, including hMPV, occurred in 3 patients. One patient with the diagnosis of bronchiolitis had both RSV and hMPV. The second patient was 3 years old with rhabdomyosarcoma of the left arm and had hMPV and cytomegalovirus, and the third patient, who was 3 years old and had myelofibrosis and who underwent unrelated cord blood transplant and developed graft-versus-host disease, had hMPV and adenovirus.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of hMPV infections.

Outcomes of hMPV infections

Outcomes of hMPV infections are listed in Table 1. Nine (75%) of the hMPV-positive patients survived, including 4 patients who required admission to the intensive care unit, while 3 (25%) patients died. One patient who died was an unrelated cord-blood transplant recipient. Among the other 2 patients who died, one had Gaucher disease, and the other had non-Hodgkin lymphoma. All deaths occurred with a median of 16 days (range, 3-30 days) after the onset of pneumonia. We did not identify any accompanying pathology or microbiological finding in these patients.

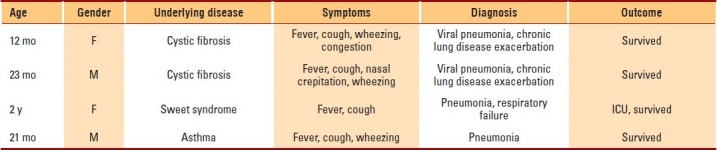

Clinical characteristics of HCoV-NL63 infections

Clinical characteristics of HCoV-NL63 infections are listed in Table 2. All 4 HCoV-NL63–positive children had underlying medical conditions. Two of them had cystic fibrosis, 1 patient had Sweet syndrome, and 1 patient had asthma. The clinical diagnosis of these patients included pneumonia in 2 and viral pneumonia causing chronic lung disease exacerbation in 2 patients. Their common presentation included fever and cough in 4 patients, wheezing in 3 patients, and crepitations in 2 patients. One patient with Sweet syndrome required admission to the intensive care unit for 4 days.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of HCoV-NL63 infections.

DISCUSSION

The general characteristics of hMPV and HCoV-NL63 highlighted by this study show strong similarities with those that have emerged from broad, previously published studies. hMPV was detected in 8.3% of those hospitalized with LRTIs. These figures are similar to those reported in Europe,1,2 the United States,3 and Australia.4 HCoV-NL63 was detected in 2.8% of specimens tested and was associated with both URTIs and LRTIs. These findings are similar to those of previous studies that reported detection rates ranging from 1.3% to 3.6% in various sample sets.5,6 We found the proportion of patients with hMPV infection was significantly higher among children 1 to 3 years old in comparison with that among younger or older children. Our results are comparable with those of van den Hoogen et al.7 The seasonality of hMPV is becoming evident. In our study, the peak incidence was in March, August and September, but there were hMPV isolates from every month of the year except for July and October. A broad seasonal activity of hMPV with distinctive pattern in different years was reported by Sloots et al.3 A previous report states that HCoV-NL63 peaked in summer, which is similar to our finding.

hMPV was associated with acute URTIs and LRTIs in our immunocompromised children. The hMPV-associated disease in hematologic malignancy and related disorders was characterized by several respiratory symptoms, including fever, nasal congestion, cough, and shortness of breath. Seven patients developed rapidly progressive respiratory failure associated with pneumonia and culture-negative shock. All patients were admitted to intensive care units. hMPV was the only respiratory pathogen detected by NPA or BAL in 4 of these patients. These findings are similar to those reported by Williams et al8,9 and Englund et al.10 Three immunocompromised patients with idiopathic pneumonia died despite aggressive therapy, suggesting involvement of hMPV as a cause of total idiopathic pneumonia. Our findings are consistent with those of investigators who have demonstrated that HCoV-NL63 was a cause of URTIs in hospitalized children with acute respiratory infection and can be associated with high risk of respiratory complications in high-risk patients.11

In summary, our data suggest that hMPV and HCoV-NL63 may play a significant role in acute respiratory illness of hospitalized Saudi children. These data support the hypothesis that hMPV is a significant pathogen in immunocompromised children, with a risk of increased morbidity and mortality. HCoV-NL63 may cause severe lower respiratory disease in those with underlying conditions. Our study has a number of limitations. It is not an epidemiological study and so may not reflect prevalence in the community; in fact, the frequency of viruses detected by molecular biological techniques are of those sampled and not of all those who are symptomatic. In addition, this study was conducted in a tertiary care facility with many immunocompromised children, a group not reflective of the general population. More comprehensive studies are needed to determine the full spectrum of presentation of hMPV and HCoV-NL63 and the impact of these viruses on the health care system in Saudi Arabia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Foulongne V, Guyon G, Rodière M, Segondy M. Human metapneumovirus infection in young children hospitalized with respiratory tract disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:354–9. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000207480.55201.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.García-García ML, Calvo C, Pérez-Breña P, De Cea JM, Acosta B, Casas I. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of human pneumovirus infections in hospitalized infant in Spain. Pediatr Pulmonology. 2006;41:863–71. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sloots TP, Mackay IM, Bialasiewicz S, Jacob KC, McQueen E, Harnett GB, et al. Human metapneumovirus in Australia, 2001-2004. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;12:1263–6. doi: 10.3201/eid1208.051239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams JV, Harris PA, Tollefson SJ, Halburnt-Rush LL, Pingsterhaus JM, Edwards KM, et al. Human metapneumovirus and lower respiratory tract disease in otherwise infant and children. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1788–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moës E, Vijgen L, Keyaerts E, Zlateva K, Li S, Maes P, et al. A novel pancoronavirus RT-PCR assay: Frequent detection of human coronavirus NL63 in children hospitalized with respiratory tract infection in Belgium. BMC Infect Dis. 2005;5:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-5-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Hoek L, Pyrc K, Jebbink MF, Vermeulen-Oost W, Berkhout RJ, Wolthers KC, et al. Identification of new human coronovirus. Nat Med. 2004;10:368–73. doi: 10.1038/nm1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van den Hoogen BG, de Jong JC, Groen J, Kuiken T, de Groot R, Fouchier RA, et al. A newly discovered human pneumovirus isolated from young children with respiratory tract disease. Nat Med. 2001;7:719–24. doi: 10.1038/89098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bastien N, Robinson JL, Tse A, Lee BE, Hart L, Li Y. Human coronavirus NL63 infections in children: A 1-year study. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:4567–73. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4567-4573.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams JV, Martino R, Rabella N, Otegui M, Parody R, Heck JM, et al. A prospective study comparing Human metapneumovirus with other respiratory virus in adult with hematological malignancies and respiratory tract infection. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1061–5. doi: 10.1086/432732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Englund JA, Boeckh M, Kuypers J, Nichols WG, Hackman RC, Morrow RA, et al. Brief communications: Fetal human metapneumovirus infection in stem-cell transplant recipients. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:344–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-5-200603070-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garbino J, Crespo S, Aubert JD, Rochat T, Ninet B, Deffernez C, Wunderli W, Pache JC, Soccal PM, Kaiser L. A prospective hospital-based study of the clinical impact of non-severe acute respiratory syndrome (Non-SARS) related human coronavirus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1009–15. doi: 10.1086/507898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]