Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate rhabdomyolysis and it's management in lithotomy and the exaggerated lithotomy positions during urogenital surgeries.

Design:

Retrospective study

Setting:

Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education and Research (IPGME & R), Kolkata, India.

Materials and Methods:

Patients undergoing urogenital surgeries (lithotomy and the exaggerated lithotomy positions).

Intervention(s):

All four cases of rhabdomyolysis which occurred after such positional urogenital surgeries were treated with conservative management for prolonged period with hemodialysis. One case which developed compartment syndrome underwent fasciotomy and also managed with conservative approach as other cases.

Main Outcome Measure:

Rhabdomylysis is now a rare complication in any open or laparoscopic surgery. But prolonged lithotomy or exaggerated lithotomy position surgeries have been shown to expose patients to the risk of rhabdomylysis and acute renal failure.

Results:

In our institute patients undergoing urogenital surgeries in lithotomy and the exaggerated lithotomy positions only developed rhabdomyolysis and myogloginuric acute renal failure. All procedures were of prolonged duration (mean five hours and ten minutes). Three patients developed rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure without compartmental syndrome and one with compartmental syndrome. Rhabdomyolysis with the appearance of acute renal failure is discussed.

Conclusion:

Overall, our cases showed that rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure can develop in such operative positions even in the absence of compartmental syndrome, and that duration of surgery is the most important risk factor for such complications. So we should be careful regarding duration of surgery in lithotomy procedure to prevent such morbid complications.

Keywords: Acute renal failure, lithotomy position, rhabdomyolysis

INTRODUCTION

This study was done to know different effects and complications of lithotomy and exaggerated lithotomy position in genitourinary procedures. Aims and objective of this study is to find out the complications and precipitating factors for them. Rhabdomyolysis, with secondary acute renal failure (ARF) may occur following urogenital surgery as a complication of operative positions.[1] These complications are mainly reported in the exaggerated lithotomy position (ELP) and less frequently in the lithotomy position (LP).[2–6]

We report four cases, three operated in the ELP and one in LP who developed rhabdomyolysis and ARF, three without compartmental syndrome or muscle injury and one with compartmental syndrome. The risk factors known to play a role in the induction of these complications are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

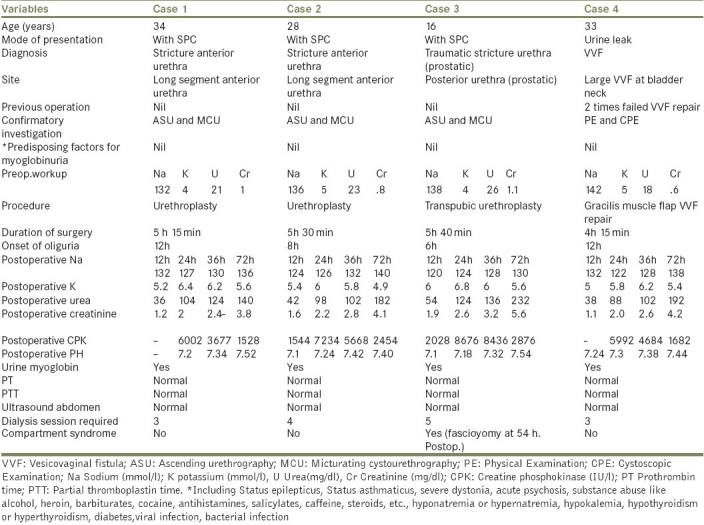

Patients of perineal surgeries including urethroplasty and vesicovaginal fistula (VVF) repair encountered in the department from August 2007 to July 2010 were evaluated for postoperative complications. Patients were evaluated for their age at presentation, clinical features, previous operation/trauma history, hemogram, renal function tests, electrolytes, site of the urethral stricture or VVF, diagnostic investigation and treatment. Patients who developed rhabdomyolysis and ARF were evaluated for preoperative predisposing factors by taking detail history like excessive muscular activity (such as Status epilepticus, Status asthmaticus, severe dystonia, acute psychosis), toxin-mediated rhabdomyolysis may result from substance abuse (alcohol, heroin, barbiturates, cocaine, antihistamines, salicylates, Caffeine, steroid), metabolic causes of rhabdomyolysis (hyponatremiaor hypernatremia, hypokalemia, hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism, diabetes),viral infection, and bacterial infection. Postoperative physical examination with laboratory investigations included sodium, potassium, urea, creatinine, creatine phosphokinase (CPK), arterial blood gas for PH send 12-hourly, urine analysis including myoglobinuria and other parameters like prothrombin and partial thromboplastin time and ultrasound done after decrease urine output [Table 1].

Table 1.

Different variables of lithotomy and the exaggerated lithotomy positions develops rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure during urogenital surgery

The patients received fluid challenge and intravenous furosemide with no effect on their oliguria. Alkalinization of the urine was started in the same setting of fluid challenge in view of the diagnosis of rhabdomyolysis with acute renal failure. The following day his CPK was lower and continued to decrease gradually thereafter. Compartment syndrome patient undergo fasciotomy by orthopedic surgeon.

Hemodialysis was started postoperatively as all patients remained oliguric, with high creatinine and features of pulmonary congestion. They needed three to five more dialysis sessions until they started to show improvement in urine output and renal function. The patients were discharged with normal renal function.

DISCUSSION

In urogenital surgery, LP and ELP are mainly used when perineal exposure is required. These positions have been reported to expose patients to rhabdomyolysis, particularly following prolonged surgeries.[1–6]

In a 1982 study of 87 episodes of rhabdomyolysis in adults, Gabow found that only 50% of patients initially complained of muscle pain. A minority of the patients reported dark discoloration of the urine. In Gabow's series, 97% of patients reported at least one risk factor for rhabdomyolysis. Fifty-nine percent reported multiple risk factors. Common risk factors included alcohol abuse (67%), recent soft-tissue compression (39%), and seizure activity (24%). Other causative factors included trauma (17%), drug abuse (15%), metabolic derangements (8%), hypothermia (4%), flu-like illness (3%), sepsis (2%), and gangrene (1%).[7] In our cases the risk factor was prolonged operative procedure that caused soft-tissue compression.

A constant and prolonged pressure of the muscle beds with elongation of muscles and arterial blood supply results in decreased blood flow and ischemia.[8] Release of potentially toxic muscle cell components into the circulation, including creatine phosphokinase and myoglobin, follows muscle necrosis.

The mechanism of renal injury in this condition is multifactorial and includes relative hypovolemia secondary to redistribution of intravascular volume into the edematous muscle tissue, intratubular cast formation with resultant obstruction; heme being the main component of these casts, and direct heme-mediated proximal toxicity.[9] Myoglobin as well, was shown to be intrinsically nephrotoxic and could precipitate acute tubular necrosis.[10] Acute renal failure develops in 30-40% of patients with rhabdomyolysis. So the suggested mechanisms include precipitation of myoglobin and uric acid crystals within renal tubules, decreased glomerular perfusion, and the nephrotoxic effect of ferrihemate (formed upon dissociation of myoglobin in the acidic environment of the renal parenchyma). Predictors for the development of renal failure include peak CK level more than 6000 IU/L and dehydration.

Targa et al.,[1] showed in their prospective study, that rhabdomyolysis was directly related to the duration of surgery, and that for a mean surgery duration of 3.5 h, acute renal failure did not occur. In almost all reported cases where acute renal failure was involved, the duration of surgery was above 5 h.[2–6] Our cases, three with more than 5 h and one with more than 4 h duration of surgery complies with this finding. However, the other known potential risk factors (i.e., hypertension, diabetes, obesity, preexisting renal failure and extra-cellular volume depletion),[3] viral infectious disease,[11] bacterial infectious agents,[12] hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism[13] were all absent in our patient. Thus, our cases reinforce and highly illustrate the statement made by Kikuno et al.,[14] advocating duration of surgery above 5 h as the most important risk factor for rhabdomyolysis and subsequent acute renal failure to occur. We believe that it is also the most important factor to consider in the prevention of such complications.

It is noteworthy that the classical symptoms of compartmental syndrome or direct muscle injury (i.e., lower back and extremity pain or swelling on the buttocks), were not found in our three patients but were present in only one patient. In this condition, the rapid increase in serum creatinine greater than 1 mg/dl per 24 h, which is highly suggestive of the diagnosis of rhabdomyolysis[15] and noticed in our patients, should be given prime importance in order to reach an early diagnosis. On the other hand, cases in the LP are very seldom reported,[14] probably because ELP is more frequently used. Cases in the LP and without compartmental syndrome, as in our cases, are even rarer, and as far as we know, only a handful of cases combining both conditions have been reported.[3,5,14] Consequently, it shows that the LP is not safer than the ELP, and that in fact, duration of surgery is the main trigger for rhabdomyolysis.

General recommendations for the treatment of rhabdomyolysis include fluid resuscitation and prevention of end-organ complications. Patients with CPK elevation in excess of two to three times the reference range, appropriate clinical history, and risk factors should be suspected of having rhabdomyolysis. Isotonic crystalloid 500 mL/h should be administered and titrated to maintain a urine output of 200-300 mL/h.

Urinary alkalinization to prevent the development of acute renal failure in patients with rhabdomyolysis has been supported by animal studies and retrospective human studies, although prospective randomized human studies are lacking. Urinary alkalinization is recommended for patients with rhabdomyolysis and CPK levels in excess of 6000 IU/L. Alkalinization should be considered earlier in patients with acidemia, dehydration, or underlying renal disease. A suggested regimen is 0.5 isotonic sodium chloride solution with one ampule of sodium bicarbonate administered at 100 mL/h and titrated to a urine pH higher than 7. After establishing an adequate intravascular volume, mannitol may be administered to enhance renal perfusion. Loop diuretics may be used to enhance urinary output in oliguric patients, despite adequate intravascular volume.

Treatment of hyperkalemia consists of intravenous sodium bicarbonate, glucose, and insulin; oral or rectal sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate); and hemodialysis. Intravenous calcium chloride should be administered to patients who are hemodynamically compromised and hyperkalemic.

Compartment syndrome requires immediate orthopedic consultation for fasciotomy.

CONCLUSION

Rhabdomyolysis, with secondary acute renal failure can occur with both the lithotomy and exaggerated lithotomy position but the most important part of the development is the duration in such a position. Finally, this condition remains widely unrecognized and more awareness by anesthetists, surgeons and nephrologists will definitely improve early diagnosis and prevention of this morbid condition.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Targa L, Droghetti L, Caggese G, Zatelli R, Roccela P. Rhabdomyolysis and operating position. Anesthesia. 1991;46:141–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1991.tb09362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali H, Nieto JG, Rhamy RK, Chandralapaty SK, Vaamonde CA. Acute renal failure due to rhabdomyolysis associated with the extreme lithotomy position. Case report. Am J Kidney Dis. 1993;22:865–9. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)70347-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biswas S, Gnanasekaran I, Ivatury RR, Simon R, Patel AN. Exaggerated lithotomy position related rhabdomyolysis. Am Surg. 1997;63:361–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gabrielli A, Caruso L. Post-operative acute renal failure secondary to rhabdomyolysis from exaggerated lithotomy position. J Clin Anesth. 1999:257–63. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(99)00033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anema JG, Morey AF, Mc Aninch JW, Mario LA, Wessels H. Complications related to the high lithotomy position during urethral reconstruction. J Urol. 2000;164:360–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orihuela E, Nazemi T, Shu T. Acute renal failure due to rhabdomyolysis associated with radical perineal prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2001;39:606–9. doi: 10.1159/000052512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gabow PA, Kaehny WD, Kelleher SP. The spectrum of rhabdomyolysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 1982;61:141–52. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angermeier KW, Jordan GH. Complications of the exaggerated lithotomy position: a review of 177 cases. J Urol. 1994;151:866–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35108-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zager RA. Rhabdomyolysis and myohemogloginuric acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 1996;49:314–26. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minigh JL, Valentovic MA. Characterisation of myoglobin toxicity in renal cortical slices from Fischer 344 rats. Toxicology. 2003;184:113–23. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00554-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lichtstein DM, Arteaga RB. Rhabdomyolysis associated with hyperthyroidism. Am J Med Sci. 2006;332:103–5. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200608000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nauss MD, Schmidt EL, Pancioli AM. Viral myositis leading to rhabdomyolysis: a case report and literature review. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27(372):e5–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.07.022. e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh U, Scheld WM. Infectious etiologies of rhabdomyolysis: Three case reports and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:642–9. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.4.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kikuno N, Urakami S, Shigeno K, Kishi H, Shiina H, Igawa M. Traumatic rhabdomyolysis resulting from continuous compression in the exaggerated lithotomy position for radical perineal prostatectomy. Int J Urol. 2002;9:521–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2002.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koffler A, Friedler RM, Massry SG. Acute renal failure due to non traumatic rhabdomyolysis. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85:23–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-85-1-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]