Abstract

Lasers have opened a new door for the treatment of various disorders. Treatment of soft tissue intraoral mucosal growth by laser has profound effect on the patient acceptability taking the functional and aesthetic factor into consideration. The patient is able to get the outdoor treatment without the phobia of local anaesthetic and is out of the clinic in few minutes in contrast to the traditional method of surgical excision. Very few cases have been reported in literature regarding treatment of mucosal growth by soft tissue lasers. We present a case of recurrent pyogenic granuloma in a patient treated with an alternative approach, that is, diode laser, without the use of anaesthesia, sutures, anti-inflammatory drugs, or analgesics. The diagnosis of this lesion is equally important for correct treatment planning.

KEYWORDS: Diode laser, pyogenic granuloma, recurrent

INTRODUCTION

Pyogenic granuloma is a relatively common benign mucocutaneous lesion. The term is a misnomer as the lesion does not contain pus nor it is granulomatous. It was originally described in 1897 by two French surgeons, Poncet and Dor.[1] It is considered as a capillary haemangioma of lobular subtype as suggested by Mills, Cooper, and Fechner, which is the reason they are often quite prone to bleeding.[2] The most common intraoral site is marginal gingiva, but lesions have been reported on palate, buccal mucosa, tongue, and lips. Extraoral sites commonly involve the skin of face, neck, upper and lower extremities, and mucous membrane of nose and eyelids.

Being a non-neoplastic growth, excisional therapy is the treatment of choice but some alternative approaches such as cryosurgery, excision by Nd:YAG Laser, flash lamp pulsed dye laser, injection of corticosteroid or ethanol, and sodium tetradecyl sulfate sclerotherapy have been reported to be effective.[1] There are only anecdotal reports of successful treatment of mucosal pyogenic granulomas with diode laser. In this report, we seek to highlight the therapeutic success achieved with diode laser in the treatment of intraoral pyogenic granuloma.

CASE REPORT

A 50-year-old female patient reported to the Out Patient Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, with a complain of localized gingival growth for 3 months. The outgrowing mass was not painful but often bled while eating, rinsing, or sometimes spontaneously. Patient reported a similar growth in the gingiva about 3 years ago, which was treated in the same institute by surgical excision.

Intraoral examination revealed an oval-shaped, pedunculated mass-like growth seen in relation to the buccal aspect of gingiva with respect to 23, 24 region, measuring approximately 2.5 × 3.5 cm. This discrete nodular, erythematous enlargement was covering almost two-third of the crown of 24 [Figure 1]. On palpation, the mass was soft to firm in consistency and readily bled on probing. Oral hygiene was well maintained, and no exacerbating factors were identified. The previous biopsy specimen turned out to be ‘pyogenic granuloma’. Based on the clinical findings and the previous biopsy report, the case was provisionally diagnosed as recurrent pyogenic granuloma.

Figure 1.

A discrete nodular, erythematous enlargement covering almost two-third of the crown of 24

No bony abnormalities were seen on intraoral periapical radiographic examination.

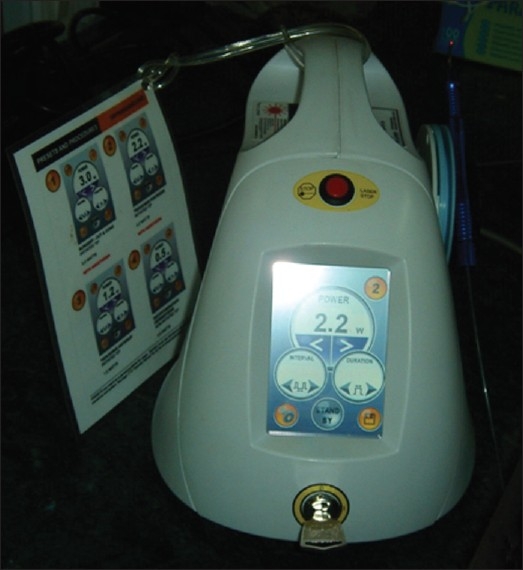

The lesion was treated by Soft-tissue Diode Laser manufactured by Picasso (Kavo, USA), with following specifications: wavelength 808 nm (± 10), output energy 0.1–7.0 W, and input power 300 VA. We used 810-nm wavelength and 7 W power, keeping it in continuous/interrupted pulse mode. Local anaesthesia was not used. The tip was kept at a distance of about 1 mm from the soft tissue throughout the procedure, and it took 4–5 min to completely excise the mass. The diode laser provided an optimum combination of clean cutting of the tissue and haemostasis [Figures 2 and 3]. Patient was discharged with all necessary post-operative instructions. She was not prescribed any antibiotics, analgesics, or anti-inflammatory medication and was subjected to routine scaling and curettage. She revisited after 5 days for follow-up visit, but failed to keep further appointments.

Figure 2.

Diode laser (Picasso-KAVO)

Figure 3.

Tip was kept almost at a distance of 1 mm from the soft tissue. Also, there was minimal bleeding during the procedure

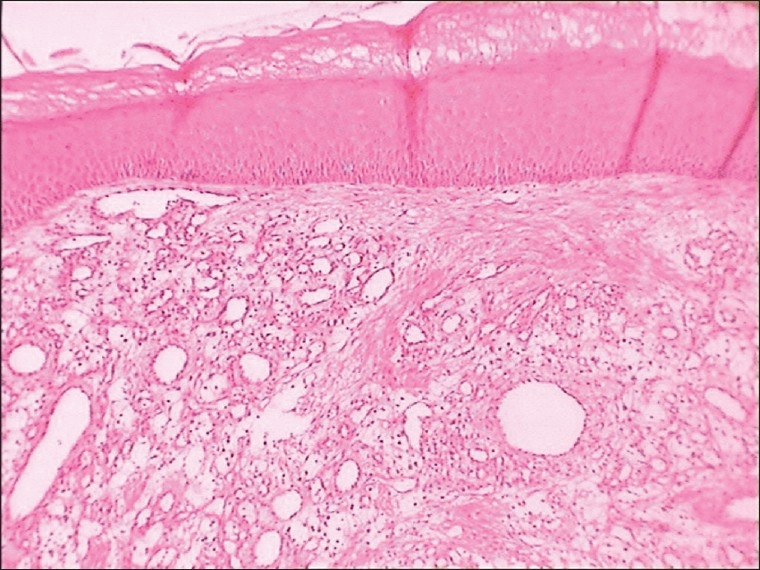

The excised mass [Figure 4] was sent for histopathologic evaluation which showed hyperplastic stratified squamous parakeratotic epithelium with an underlying fibrovascular stroma. The stroma consisted of a large number of budding and dilated capillaries, plump fibroblasts and areas of extravasated blood, and a dense chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate. The above histopathologic features were suggestive of pyogenic granuloma [Figure 5].

Figure 4.

Excisional biopsy specimen

Figure 5.

Photomicrograph of histopathological section under low magnification (10×)

DISCUSSION

Although pyogenic granuloma may appear at any age, 60% cases are observed between the ages of 10 and 40; incidence peaks during the third decade of life and women are twice as likely to be affected. It is more common in children and young adults.[3]

The clinical presentation is generally of a dull red, sessile, or pedunculated smooth surfaced nodule that may easily bleed, crust, or ulcerate. Lesions may grow rapidly, reach its maximum size, and remain static.[4] They may typically begin as small, red papules that rapidly enlarge to become pedunculated raspberry-like nodules. Rarely, patient may develop multiple satellite angiomatous lesions after excision of a solitary pyogenic granuloma.

Oral pyogenic granulomas show a striking predilection for the gingiva as seen in the present case, which accounts for 75% of all cases. Gingival irritation and inflammation that result from poor oral hygiene may be a precipitating factor in many patients. The lip, tongue, and buccal mucosa are the next most common sites.[5,6]

In majority of cases, minor trauma and/or chronic irritation are cited in the etiopathogenesis of pyogenic granuloma.[7] Infection may play a role with suggestions of agents such as streptococci and staphylococci.[8] Recently, angiopoietin-1,2 and ephrin B2[9] agents in other vascular tumours such as Bartonella henselae, B. quintana, and human herpes virus 8 have been postulated to play a part in recurrent pyogenic granuloma.[10] Multiple pyogenic granulomas with satellite lesions may occur as a complication of tumour removal or trauma.[11] Viral oncogenes, hormonal influences, microscopic arteriovenous malformation along with inclusion bodies and gene depression in fibroblasts have all been implicated.[12,13]

Differential diagnosis of pyogenic granuloma includes haemangioma,[5] peripheral giant cell granuloma, peripheral ossifying fibroma and metastatic carcinoma, and amelanotic melanoma.[6]

Although the conventional treatment for pyogenic granuloma is surgical excision, a recurrence rate of 16% has been reported.[14] There are also reports of the lesion being eliminated with electric scalpel or cryosurgery.[15] Other methods used by various workers include cauterization with silver nitrate, sclerotherapy with sodium tetra decyl sulfate and monoethanolamineoleate[16] ligation, absolute ethanol injection dye,[17] Nd:YAG and CO2 laser,[18] shave excision, and laser photocoagulation.[19]

Laser therapy using continuous and pulsed CO2 and Nd:YAG systems have been used for a variety of intraoral soft tissue lesions such as haemangioma, lymphangioma, squamous papilloma, lichen planus, focal melanosis, and pyogenic granuloma, because they carry the advantage of being less invasive and sutureless procedures that produce only minimal postoperative pain. Rapid healing can be observed within a few days of treatment, and as blood vessels are sealed, there are both a reduced need for post-surgical dressings and improved haemostasis and coagulation. It also depolarizes nerves, thus reducing post-operative pain, and also destroys many bacteria and viral colonies that may potentially cause infection. Reduced post-operative discomfort, oedema, scarring, and shrinkage have all been associated with its use.[19]

White et al proposed that laser excision is well tolerated by patients with no adverse effects. They also stated that CO2 and Nd:YAG Laser irradiation is successful in surgical treatment.[1] Meffert et al used the flash lamp pulsed dye laser on a mass of granulation tissue and concluded that previously resolute tissue responded well to the series of treatments with pulsed dye laser.[1] Diode laser has shown excellent results in cutaneous pyogenic granulomas with only minimal pigmentary and textural complications. Gonzales et al[21] demonstrated both symptomatic and clinical clearing of the lesions with excellent cosmetic results in 16 of 18 treated patients. However, there is minimal convincing proof of its efficacy in intraoral pyogenic granuloma. We achieved complete resolution of this lesion located on the upper gingiva with diode laser without producing any complications. There was no scarring or recurrence. Hence, diode laser may be a good therapeutic option for intraoral pyogenic granulomas.

In conclusion, the use of laser offers a new tool that can change the way in which existing treatments are performed, or serve to compliment them. Modern medicine needs to explore and take advantage of current trends to derive maximum benefit in terms of technology, patient's acceptance and, post-operative management.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jaferzadeh H, Sanadkhani M, Mohtasham M. Oral pyogenic granuloma: A review. J Oral Sci. 2006;48:167–75. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.48.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shafer, Hine, Levy . In: Textbook of oral pathology. 5th ed. the Netherlands: Elsevier Publication; 2006. pp. 994–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nthumba PM. Giant pyogenic granuloma of the thigh: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:95. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-2-95. Available from: http://www.jmedicalcasereports.com/content/2//95 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquet JE. In: Oral and maxillofacial pathology. 3rd ed. the Netherlands: Elsevier; 2004. pp. 176–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wood NK, Goaz PW. In: Textbook of differential diagnosis of oral and maxillofacial lesions. 5th ed. USA: Mosby; 1997. pp. 32–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenberg MS, Glick M, Ship JA. In: Burkett's textbook of oral medicine. 11th ed. USA: BC Becker Inc; 2008. pp. 131–2. [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacLeod RL, Soames J. Epilides: A clinicopathological study of 200 consecutive lesions. Br Dent J. 1987;163:51–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4806194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levy I, Rolain JM, Lepidi H. Is pyogenic granuloma associated with Bartonella infection? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1065–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan K, Jin YT, Lin MT. Expression of tie-2, angiopoietin-1, angiopoientin-2, Ephrin B2 and EphB4 in pyogenic granuloma of human gingival implicates their roles in inflammatory angiogenesis. J Periodont Res. 2000;35:165–71. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2000.035003165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janier M. Infection and angiomatous cutaneous lesions. J Mal Vasc. 1999;24:135–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taira JW, Hill TL, Everett MA. Lobular capillary hemangioma (pyogenic granuloma) with satellitosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:297–300. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70184-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies MG, Borton SP, Atai F. The abnormal dermis in pyogenic granuloma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;31:342–4. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(80)80392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vilman A, Vilman P, Vilman H. Pyogenic granuloma. Evaluation of oral conditions. Dr J Oral Maxillfac Surg. 1986;24:376. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(86)90023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newman, Takei, Carranza . In: Textbook of Carranza's clinical periodontology. 10th ed. the Netherlands: Elsevier Publication; 2006. pp. 176–77. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta R, Gupta S. Cryo-therapy in granuloma pyogenicum. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:14. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.31912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsumoto K, Nakanishi H, Seike T. Treatment of pyogenic granuloma with sclerosing agents. Dermatol Surgery. 2001;27:521–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2001.01039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ichimiya M, Yoshikawa K, Hamamoto Y, Muto M. Successful treatment of pyogenic granuloma with injection of absolute alcohol. J Dermatol. 2001;31:342–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2004.tb00682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raulin C, Greve B, Hammes S. The combined continuous-wave/pulsed carbon dioxide laser for treatment of pyogenic granuloma. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:33–7. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirschner RE, Low DW. Treatment of pyogenic granuloma by shave excision and laser photocoagulation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:1346–69. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199910000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boj JR, Hernandez M, Poirier C, Espasa E. Treatment of pyogenic granuloma with a laser – powered Hydrokinetic system: Case report. J Oral Laser Appl. 2006;6:301–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonzales S, Vibhagool C, Falo LD, Jr, Momtaz KT, Grevelink J, Gonzalez E. Treatment of pyogenic granulomas with the 585nm pulsed dye laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:428–31. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90610-6. phosphatidyl choline and deoxycholate (50 mg/ml) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]