Abstract

Mexican American (MA) girls are entering puberty earlier than in the past, yet few studies have explored the perceptions surrounding puberty among this group. We conducted separate focus groups for fathers, mothers, and daughters aged 6 to 12 years to explore perceptions of body image, pubertal development, communications, and sources of puberty-related information in MA participants. Our results revealed parental concerns about daughters’ weight and pubertal development, as well as differences in their communication with their daughters. Although both parents willingly discussed pubertal issues concerning their daughters, mothers had a more active role in conveying pubertal information to daughters. Among the girls, there was a gap in knowledge about the pubertal process between the younger and older girls. Our findings present opportunities and challenges for addressing obesity as a pubertal risk factor in MA girls; however, more studies are needed to understand family beliefs and sociocultural dynamics surrounding puberty in MAs.

Keywords: adolescents, female, body image, families, fathers, focus groups, Mexican Americans, relationships, mother–child, women’s health, young women

The onset of puberty is a significant milestone for young girls in the transition from childhood to womanhood. For most girls, this period is marked by ambivalence, fear, and frustration; for parents, it is a time of struggle, perplexity, and changes in their relationships with their daughters (Doswell & Vandestienne, 1996; Graber, Seeley, Brooks-Gunn, & Lewinsohn, 2004; Siegel, Yancey, Aneshensel, & Schuler, 1999). Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) suggest that Mexican American (MA) girls in particular enter puberty even earlier than their non-Hispanic White (NHW) peers (Himes, 2006; Sun et al., 2002). Additionally, several studies have shown that girls who mature earlier than their peers tend to have lower self-esteem, and initiate alcohol use and sexual activity at an earlier age (Caspi & Moffitt, 1991; Costello, Sung, Worthman, & Angold, 2007; Doswell & Vandestienne, 1996)

Social and emotional problems encountered during puberty might be mediated by parental guidance and social support. Girls who receive parental advice and insight about puberty are more likely to experience pubertal changes with less fear, shame, and dysfunction than those without parental support (Teitelman, 2004). Although many studies have captured the cultural, social, and emotional factors affecting the perceptions of puberty by young women, the literature describing MA girls’ perceptions of puberty remains limited in scope (Beausang & Razor, 2000; Bratberg, Nilsen, Holmen, & Vatten, 2005; Cachelin, Monreal, & Juarez, 2006; Ellis, 2004; Huerta & Brizuela-Gamino, 2002; O’Sullivan, Meyer-Balhburg, & Watkins, 2000). Additionally, to our knowledge, familial attitudes toward such changes in the context of the MA community have not been reported.

In this study we sought to elucidate the perception about puberty in the MA mother–father–daughter triad by conducting focus groups examining perceptions of body image, pubertal development, interaction dynamics, and sources of puberty-related information. First, we evaluated parental perceptions of their daughters’ health, body image, body size, and pubertal development in conjunction with the daughters’ perceptions of these factors. Second, we explored the communication and interaction dynamics related to the above-mentioned factors in the parent–daughter dyads. Finally, we identified the sources of information used by parents to educate their daughters about puberty and those used by daughters to formulate body image and beliefs about pubertal development. Although our aims were exploratory in nature, the results provide important information with implications for public health interventions incorporating a family-based approach to understanding and addressing sociocultural dynamics surrounding puberty among MA girls.

Background

Puberty is characterized by Stage 2 of five distinct stages of breast and pubic hair development. On average, girls enter puberty about 2 to 3 years prior to menarche. In the United States, the average age at onset of puberty in girls is 10.5 years, whereas the onset of menarche occurs at 12.8 years (Pinyerd & Zipf, 2005). Based on national data from 1988 to 1994, the number of 10- to 11-year-old MA girls classified as Stage 2+ has significantly increased over time, from 40% to 70% for breast development and from 24% to 62% (p < .05) for pubic hair development, respectively (Sun et al., 2005). This rate of increase of MA girls is faster than the rate of NHW girls.

According to Doswell, Millor, Thompson, and Braxter (1998), body image is “an individual’s mental representation of his/her body.” However, the concept of body image is also influenced and shaped by values and experiences of family, friends, and the media, as well as one’s cultural background (Cachelin et al., 2006; Snooks & Hall, 2002). For prepubertal and peripubertal girls, body image plays an important role in mental health and emotional well-being. Early pubertal timing can potentially alter a girl’s mental representation of her body by perpetuating negative feelings about her body image and self-esteem brought on by physical changes such as weight gain and premature development of secondary sexual characteristics. In fact, both early pubertal timing and weight gain have been associated with a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms and negative body image among young girls (Huerta & Brizuela-Gamino, 2002; Siegel et al., 1999; Tremblay & Frigon, 2005). Furthermore, girls who matured earlier than their peers were significantly more likely to report dissatisfaction with their body image than those who matured at the same time as their peers (Michaud, Suris, & Deppen, 2006).

Recent epidemiological studies have indicated that the secular trend in increasing body mass index is strongly associated with an earlier age at puberty, and have implicated these findings in the continuum of the life course of breast cancer (De Assis & Hilakivi-Clarke, 2006; Hodgson, Newman, & Millikan, 2004; Lof, Sandin, Hilakivi-Clarke, & Weiderpass, 2007; Michels & Xue, 2006). Therefore, overnourishment might be responsible for triggering the earlier age of onset of puberty among girls (Karlberg, 2002; Wattigney, Srinivasan, Chen, Greenlund, & Berenson, 1999). With more than 22% of MA children at risk for overweight, the potential for negative health outcomes, psychological problems, and emotional disorders requires special attention, especially among girls who are maturing early (Flegal, Ogden, & Carroll, 2004; Hernandez-Valero et al., 2007).

During puberty, girls experience a shift in their social environment marked by increasing psychosocial conflicts with family, peers, and authority figures (Remschmidt, 1994). Girls experiencing earlier pubertal onset are more likely to report having emotional problems and to engage in high-risk behaviors, such as smoking and early initiation of sexual activity, compared with their peers (Ellis, 2004). Consequently, help-seeking behaviors, social dynamics, and emotional well-being of these adolescents tend to be lower compared to those who experience later pubertal onset (Offer, Howard, Schonert, & Ostrov, 1991; Siegel et al., 1999). Although some adolescents experiencing emotional problems tend to withdraw into themselves, more than 75% reported discussing their problems with their peers and 55% reported discussing their problems with parents (Offer et al., 1991). Therefore, communication with parents and peers might play a role in providing the social support that helps adolescents effectively transition into adulthood.

Cultural dynamics have been reported to play a role in the perception of body image and puberty among women of various ethnic backgrounds (Olvera, Suminski, & Power, 2005; Skandhan, Pandya, Skandhan, & Mehta, 1988; Snooks & Hall, 2002). In most cultures, girls usually turn to their mothers or a female caretaker as their primary source of such information. In terms of puberty, mothers’ perceptions seem to influence daughters’ perceived experiences such that a negative view of puberty presented by the mother will likely result in similar views on the part of the daughter (Marvan, Vacio, Garcia-Yanez, & Espinosa-Hernandez, 2007). As a result, this mother–daughter relationship has the potential to negatively influence how daughters perceive their body image and puberty. Conversely, assimilation into a new culture can alter the influence of the mother–daughter relationship (Saracho & Spodek, 2008). For instance, Hispanic women tend to regard as ideal a heavier body weight than NHWs, and exhibit less body dissatisfaction, whereas MA girls with a greater level of assimilation prefer a thinner body size as their ideal than those with less acculturation (Olvera et al., 2005).

Unlike mother–daughter relationships during adolescence, less is known about the influence of the father’s view on his daughter’s perception of puberty. Kalman (2003) reported that female adolescents who lived with their fathers as a primary caretaker believed that their fathers lacked credibility regarding pubertal issues, and were embarrassed to discuss such information with their fathers. Recently, Saracho and Spodek (2008) presented a review exploring the complexity of MA fathers, suggesting that MA fathers play a central role in the family’s decision-making process and that research excluding fathers could be missing crucial elements of fathers’ involvement and influence in their children’s lives.

Studies describing sexual growth and development tend to address women’s attitudes toward and perceptions of menarche, rather than puberty, and are limited by their retrospective design based on lengthy recall. Furthermore, the perceptions of puberty and body image in MA mother–father–daughter triads—and interrelated cultural factors—have not been investigated. To our knowledge, no study has assessed parental involvement in educating MA daughters about puberty, nor have the dynamics of MA parent–daughter relationships during this period been explored. Therefore, as part of a larger study on factors influencing the age of onset of puberty among MA girls, we conducted focus groups with girls aged 6 to12 years and their parents to evaluate the perceptions of and communications about puberty among MA families.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Mothers, fathers, and daughters were recruited for this study from the Mano a Mano (hand to hand) cohort (MMC), a population-based infrastructure (a prospective cohort) of lower socioeconomic status Mexican American households developed and maintained by the Department of Epidemiology at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas beginning in July 2001. A description and enrollment methodology for the cohort have been previously published (Wilkinson et al., 2005). After institutional review board approval, a list of eligible participants was generated from the MMC database. From this list, an MMC staff member who had prior contact with the families called mothers of girls aged 6 to 12 years and asked whether they and their daughters would be interested in participating in a focus group about growth and development. All mothers were also asked whether the father of the child would like to participate in the study. Both parents could participate if they had a daughter between the ages of 6 and 12 years; however, attendance of mother–father dyads was not a required criterion for participation. Once participants agreed to join the focus group, follow-up phone calls were made to confirm attendance.

Focus groups

Three sets of focus groups were conducted over the course of the study, with a total of 37 participants (8 fathers, 13 mothers, and 16 daughters). All focus groups were conducted separately for mothers, fathers, and daughters. Each set of focus groups was conducted on Saturday mornings for approximately 1 to 1.5 hours at a location convenient to the participants. Transportation was provided for those who did not have a car. At the end of the focus groups, parents received a modest monetary compensation for their time, and each girl received a doll of her choice.

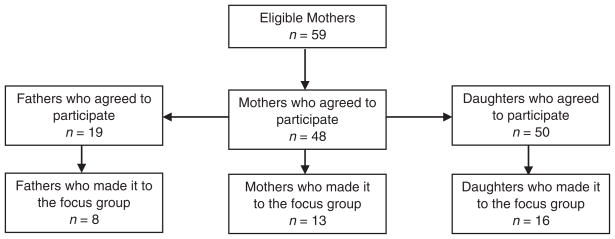

Figure 1 presents a depiction of recruitment results, showing mothers as our primary unit of recruitment. A total of 59 eligible mothers were contacted to participate in the study, of whom 48 agreed to participate in the focus group activities with their daughters; only 13 mothers actually attended the focus groups. Compared with the mothers, fewer fathers (n = 8) agreed to participate, mainly because of their work obligations on the weekends. One of the fathers who participated identified himself as a widower during the focus group. Sixteen girls took part in the focus group activities, two of whom were sisters and one who came from a single-parent household. Our high nonresponse rate was mainly attributed to cancellations the day of the focus group because of family emergencies and work obligations for both mothers and fathers.

Figure 1.

Recruitment of Family Triads

Experienced bilingual women and men moderated the mother and father focus groups, respectively. Likewise, an experienced moderator and an elementary school teacher were in charge of the girls’ discussions. Comoderators were present to assist in taking notes and recording focus group activities. Additionally, a tape recorder was used to record the focus group discussions. The parental focus groups were guided by a set of pretested questions (hereafter referred to as the “guidelines”), whereas the daughters’ focus groups were intentionally less structured to encourage conversational flow among the girls. Prior to starting each focus group session, the principal investigator (PI) explained the purpose and protocol of the study, and all participating parents gave their informed consent and the girls gave their assent to participate.

Parental focus groups

All parental focus groups were conducted separately for mothers and fathers, and discussions were in Spanish. The guidelines for both sets of parents were divided into four sections that primarily addressed questions regarding the daughters. The first section addressed the parents’ perceptions of their own health and body size and that of their daughters. Additionally, mothers were asked to describe their puberty experience when they were younger. The second and third sections transitioned into parental perceptions of their daughters’ pubertal development. Finally, the last section examined sources of information with which parents educated their daughters about body image, body size, and puberty.

Daughters’ focus groups

Focus group sessions for the girls were in both English and Spanish, based on the girls’ preferences, and were loosely structured to incorporate arts and crafts activities. Each focus group started with the girls making posters of their favorite activities and discussing typical daily activities and interactions with friends. After the moderators had established a level of comfort within the focus group, the girls were asked how their bodies had changed so far, how they would continue to change, and what they thought about such changes. Several sets of pictures were presented to foster discussions about health, body size, and body image. The girls were also asked to discuss their relationships and interactions with their mothers or others who served as female role models.

During the second half of the discussion, the girls were separated into two age groups: 6- to 9-year-olds and 10- to 12-year-olds. First, the moderators gauged the younger girls’ level of knowledge with a question about whether they had heard the word “puberty.” If so, the moderator proceeded with the next set of questions about signs of puberty and how the girls knew their bodies were changing. If the girls indicated that they were not familiar with the word puberty, the moderator briefly defined puberty and proceeded to the next set of questions. For girls aged 10 years or older, similar questions were posed in more detail.

Data Analysis

Moderators and a research assistant provided a summary and a verbatim transcript from each focus group. Spanish-language transcripts were then translated into English by a research assistant fluent in both languages. Furthermore, the accuracy of the translation was confirmed by each of the moderators. These transcripts and summaries, combined with notes taken by the PI and the first author, were synthesized for the purposes of this article. Starting with the questions in the guidelines, we collected relevant information from reading the summaries, transcripts, and notes to analyze the results from each set of focus group sessions. We analyzed responses to the guideline questions from each focus group separately, and identified common issues that emerged in the context of previously known data. Subsequently, in-depth analysis of the focus group data identified similarities and differences in themes assessed by each researcher across all focus groups. Moderators and researchers met several times to compare and contrast the content that each had included in his or her assessment of relevant data on a topic. Conclusions and analyses that were different from one researcher to another were discussed in a group setting until a consensus was reached. After reaching a consensus on the emergent themes, we summarized the salient points from each focus group discussion.

Results

Most of the parents in our sample were born in Mexico and had less than a high school education. The mean ages for the mothers and fathers were 34.8 years and 38.5 years, respectively. Even though most of the mothers and fathers indicated that they had lived in the United States for more than a decade, they preferred to speak, watch television, listen to the radio, and read in Spanish. On the other hand, all of the girls (ranging in age from 6 to12 years, with a mean age of 7.94 years) were born in the United States and could communicate in both English and Spanish. Throughout the focus group discussions, the younger girls seemed more comfortable with Spanish, whereas the older ones preferred English as their primary language of communication; this was likely a function of years in school and peer influence.

Parental Perceptions

Health and body size

The majority of the parents expressed contentment and felt comfortable with their weight, whereas a few stated there was room for improvement. With regard to their daughters’ health and body sizes, fathers were careful to avoid portraying their daughters in a negative light, whereas few mothers verbalized any concerns about their daughter’s height and weight. Of all the mothers, only one expressed the belief that her daughter was not very healthy because the doctor had put the child on a diet. The rest of the mothers thought that their daughters were healthy irrespective of their body size.

Fathers and mothers openly discussed the biological and social impact of being overweight or underweight. One father explained that being “too skinny” could affect the immune system, whereas being overweight could affect a child’s heart and prevent her from participating in sports because she would tire faster than thinner girls. Furthermore, some fathers expressed that overweight girls would suffer from more emotional problems and early pubertal development than would those who were not overweight. One father stated, “If a young girl is overweight, she tends to develop more rapidly—her hormones work harder, and [she has] body discharge and breast development too early.”

Similarly, several mothers explained that being either too thin or overweight could equally result in health consequences, teasing, and criticism. Two mothers mirrored some of the fathers’ thoughts, with one mother saying, “When they [the girls] are overweight, they develop faster than when they are thinner.” The other mother agreed, saying, “I think the same, because my daughter is thin and I don’t see her developing. Other girls in her class are taller and are growing faster because of their weight.”

In general, fathers and mothers thought that their respective daughter’s weight and height were normal, even when the daughters themselves expressed insecurity about their height and weight in comparison to that of their peers. Although some of the mothers thought that their daughters were slightly bigger than average, they did not think the girls needed to lose weight. Listed in Table 1 are various concerns expressed by some fathers and mothers about their respective daughter’s health.

Table 1.

Selected Questions and Responses Involving Parental Perceptions

| Topics | Questions | Quotes

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers | Fathers | ||

| Health and body size | Do you think your daughter’s body is healthy? Why? Why not? | “Well, my [daughter] is a little bit big, because even the doctor told me that she needed to lose a little bit of weight. … Right now she weighs ninety pounds and he told me [referring to the daughter] to lose weight. He didn’t tell how much, but he did tell me [she needs] to lose some weight.” | “I think she is, well … she is not obese. She might be a little overweight, but she is controlling herself.” “She is not fat because she has big cheeks. All of them [kids at school] tell her that she is fat … [but] she has a good weight for me.” “I thought it was a lot, 70 pounds. I didn’t want to say anything, because she’s going to grow. If the doctor tells me that I have to remove food … how will I do this?” |

| Pubertal development | How does it make you feel to know that your daughter’s body is changing? In what ways are you seeing your daughter’s body change as she gets older? Do you talk with her about it? Do you have books to refer her to? |

“I tell my daughter that it is all normal and she has to go through certain stages in life. I have talked to her about it. The other day, not too long ago, a girl at school the same age as my daughter was scared, because she sat down and she had … [bleeding] … and so my daughter told her that I said it was normal. She thought she had cut her legs. Her mom never told her about that.” “I do tell her to calm down because it’s the age [of puberty] and everybody says so; I have one [friend] that tells me, ‘No, no, right now is not the time to tell her [about puberty].’ They say that we talk to them and they explode [get upset].” “Well, I started to tell her [before]; this [menses] is going to be every month. You have to be careful. You need to start checking on what day [to expect menses] and everything.” |

“I see that she is changing a lot. Every time I see her, [she is] more like a senorita. Older per se … I feel happy—at the same time, worried—because the older they get, the more problems.” “Well, I feel good. I feel happy because as the years pass by, well … they are not girls anymore. They stop being girls; then comes another step. It’s not the same. Nowadays, the girls become senoritas at a young age.” “It’s [their interaction with their daughter] not the same … it is different than when she was 2 or 3 years old…. I used to play with her a lot before and now, with me … I can’t … and it doesn’t look right.” |

Pubertal Development

To broach the subject of puberty, the fathers were asked whether they had seen changes in their daughters’ bodies and how they felt about those changes. Some of the fathers expressed happiness with their daughters becoming young women, but many worried about the pace at which the girls were developing. In contrast, the mothers were asked whether they talked to their daughters about puberty, and the age at which they thought it appropriate to do so. A majority of the mothers said they were comfortable talking to their daughters about puberty, given that the girls had begun to show signs of puberty or had directly asked a question about the topic. The mothers of the younger daughters did not always feel comfortable talking about puberty with their daughters, and differed on the appropriate age for the discussion and how to approach the topic with the girls. The differences of opinion between the mothers and fathers are also listed in Table 1.

Father–daughter interaction and communication dynamics

Fathers were asked whether they communicated directly with their daughters or through their wives. All fathers except two mentioned that they talked to their spouses about all issues concerning their daughter’s body weight, growth, and attire; very few communicated directly with their daughters. Some fathers explained that they were more “hands-off” when it came to discussing puberty with their daughters, and that the mothers were responsible for addressing these issues with the girls. However, about half the fathers, including a widower, said they played a very active role in communicating with their daughters about their daughters’ development. One father, explaining the importance of the father–daughter relationship, stated the following:

I believe that [knowing your children]; that is where you avoid any problems. When we don’t know our own children … and when we leave the father stuff for the mother and everything, that is where the problem is…. Well, how am I going to know if my daughter has an infection there and she never tells me because I am her father? If my daughter has an infection, she comes and tells me, “You know, my part hurts and I have this.” Because she trusts you. If she tells the mother and the mother is irresponsible and the father does not know and the mother just leaves it there … I believe each one of us is responsible for our children, mother and father, equally. That is the way I see it.

Two other fathers went on to explain how having a relationship with their daughters provided an environment of trust and comfort for the girls, adding:

We are always going to be their fathers and they have to trust and talk to us about anything. Me, at least, that is what I have instilled in them. Whatever problem they have, whatever it is … for them to come and talk to me and, yes … with them, well, you know [it] is for their own good.

[Menarche] is an added expense. What I mean is, if there is something that they need, I buy it for them, whatever it is. There are three ladies [in my household]. Now, for everything, we have to buy pads. For example, buying one for her and one for your wife is a lot. But for us, it was two cases at the same time. It’s always more expensive. That is part of their physique, right? What can you say? “Don’t ask, girls. Don’t ask your father because it’s embarrassing?” If they tell you, “I need them because my period is coming,” I go and I bring it to them. I am not embarrassed to go to the store to buy them, because that was the way I was brought up. It’s something normal.

When asked whether they participated in any activities with their daughters, most of the fathers mentioned spending time with their daughters walking, playing sports, and reading to them. However, they expressed regrets about not having more time to interact with the girls and play a more active role in their lives because of work obligations.

Mother–daughter interaction and communication dynamics

Unlike the fathers, mothers seemed to benefit from a greater level of interaction with the girls. In many circumstances, they served as the primary source of information for the girls regarding pubertal changes. At the same time, they served as a liaison, relaying information about the daughter to the father. In general, the mothers were comfortable discussing the topic of puberty with their daughters, especially if the daughter initiated the conversation; several of them explained how they talked to their daughters about what was soon to happen to the girls’ bodies. However, some mothers chose to wait until menarche actually began, or chose to leave pubertal education entirely up to the school, an older sister, or an aunt. A subset of the mothers expressed that they did not think they were ready to broach the issue with their daughters, stating the following opinions:

Well, my daughter is young and … she is 8 years old. About a month ago, she was lying down and she told me, “Come over here mom!” and I say, “Yes.” She says, “Mom, when am I going to be big?” [referring to breast development]. And I tell her, “When time passes by, because right now, you are barely 8 years old.” And then she says, “I want to tell you something.” I ask her, “What?” She told me, “It’s because my friend has a lot of this area [breast development] and I also want it.” I tell her, “No, later you are going to get some…. You’re still a little girl.” And she starts laughing. And then, she tells me, “Mom, when am I going to be a lady?” I tell her, “When time passes by.” It’s like she has a lot of discomfort because she is always asking me, “Mom this” and “Mom that.” And sometimes she tells me, “You get mad because I tell you?” And I tell her, “No, [daughter’s name], on the contrary, I want you to ask me. Yes.”

Well, I don’t know if she knows … I hardly ever talk to her. She just goes to school, to church, and sometimes she goes out with friends and I go pick her up. But she really doesn’t ask me anything and I don’t bring it up either.

Other mothers who mentioned discomfort discussing pubertal issues with their daughters expressed not feeling comfortable, secure, or educated enough to talk to the girls about puberty. Conversely, two mothers who had taken a class offered through their community center explained that they were somewhat more comfortable in talking to their daughters because the class taught them how to explain pubertal development to girls in a way the girls could understand.

Mothers’ experiences during puberty

In addition to communications about pubertal growth with their own daughters, the mothers were asked to recall their own pubertal experiences and to describe the relationship they had with their mothers during that time, as well as the sources of information they had about puberty. Several mothers recalled difficulty going through puberty; some recounted not knowing what would happen to their bodies and others recalled embarrassment.

Most mothers reported having a somewhat strained relationship with their own mothers during puberty because they did not feel comfortable talking to them about the changes in their bodies. Only two of the mothers named their mothers as the primary source of their education about puberty. Some had mothers who did not talk to them about puberty until after their first menses had occurred. For others, the communication that took place was superficial, at best. Some mothers recalled learning what they needed to know from a close friend or relative. Below are personal accounts of three mothers’ experiences of pubertal development:

I was shy, I was always putting on sweaters, so they [people] wouldn’t see me. When they [breasts] were growing a little bit, I was always covering myself because I didn’t want anybody to see me.

Well, after it happened to me, she just told me to be careful and try to place whatever you put on correctly. If not, you are going to embarrass yourself. After that, she would tell me she regretted not preparing me for it. She never talked to us.

Well, look, my parents never told me anything. I found out through my cousins that were older than me. And they told me, “This is going to happen and this is going to happen.” And when I became a lady, I also was very young—about 10—and I already knew.

Sources of information about daughters’ pubertal development

Most parents indicated that they learned of their daughter’s development mainly through observation and, sometimes, by talking to them. In terms of resources used to educate their daughters, most mothers based their advice on experience; some of the mothers mentioned classes that were offered through their community centers and others explained that information about puberty is provided to the girls through school. Two mothers expressed the desire to learn more about the topic so they could better explain the process to their daughters, and another, who had attended a class to teach her how to communicate with her daughter, shared her experience by stating:

We need to educate ourselves a little bit more. Go to talks without being shy.

She [daughter] asks me [about puberty] and I try to explain the best I can so she can understand. I don’t like to lie to her.

Yes because [in the class] you learn, because no one ever teaches you how to explain things to your kids.

Not all of the parents were certain of the sources used by their daughters to learn about puberty. They did expect that the school and peers would play major roles in such education. Some mothers indicated that girls are shown a video about puberty in the fifth grade. The mothers thought this instruction, along with information from magazines, television, family members (such as older cousins), or friends would be adequate. Although the fathers were not specifically questioned regarding sources of information used by their daughters, they did list the media as very influential in shaping their daughters’ perceptions and attitudes toward clothing, boys, and body image.

Daughters’ Perceptions

Health and body size

When asked how they felt about their bodies, the majority of the girls reported that they felt good about their bodies. However, a few did not think their bodies were in optimal condition because of occasional illnesses. The girls gave a variety of answers about what they did to keep in shape. First, they mentioned eating healthy, “good” foods, such as milk, juice, fruit, and vegetables. They also reported taking part in physical activities such as running, walking, racing, doing cartwheels, dancing, doing jumping jacks, and riding bicycles.

Body image

When asked whether they used a mirror, the majority of the girls said they avoided doing so because it made them feel ugly. They made exceptions for when they were going to an event. About half of the girls used negative words such as “short,” “fat,” and “ugly,” to describe themselves, and indicated comparing their bodies to the bodies of other girls at school. One girl even mentioned using a measuring tape to measure whether she was taller than her friend. Some of these negative images seemed to be reinforced by either family members or peers. For instance, one of the girls said, “My mom tells me to run so I can lose weight. I run in a square in my house…. When I run she tells me I look skinnier…. I feel good.” The same girl went on to say that she felt bad about being fat because the doctor had put her on a diet, whereas her friends were not on a diet. She also reported boys teasing her when she was fat but not when she was skinny. Another girl recounted receiving a positive statement about her body, saying, “I feel proud because my friends tell me I am thinner than they are.”

Pubertal development

Most of the younger girls were not familiar with the word “puberty” prior to the moderator’s brief explanation. However, one of the older girls explained that puberty was “the changes in your body.” A majority of the girls recalled having learned about certain aspects of growth and development through television shows, their school nurse, from a healthy body Web site, and gym classes—but were still not quite sure what the whole process entailed. In terms of how they saw themselves changing, the younger girls believed that they would grow taller, eat more, have longer hair, have better teeth, become thinner, and that their faces would change as they grew older. In contrast, two of the older girls (who had started their menstrual cycles) mentioned breast development as one of the changes that would occur.

Some of the younger girls stated that they felt good about the upcoming changes in their bodies and were looking forward to growing up. They associated their growth and development with a greater sense of freedom and seemed happy about growing up because it meant they could participate in more activities, such as going on more field trips than younger children. However, one girl did report feeling sad because growing up meant she would have to do more homework. In general, the girls assumed that pubertal changes would occur between the ages of 11 and 20 years, with 15 years being the “norm” most often cited.

Daughters’ Communication With Parents and Peers

All the girls said they had a good relationship with their mother, and felt they could talk to their mother about most things except boys or specific changes in their bodies. For the most part, the girls reported that they got along with their mother and were appreciative of her as a mentor with whom they could talk. They reported conversations with their respective mother about their growth, grades, school activities, and the future. Speaking of her relationship with her mother, one of the girls explained, “Sometimes we get along good, sometimes bad.” Another girl said, “We talk about exercises that we do to lose weight.” Most of the girls could recall at least one enjoyable activity in which they regularly participated with their mothers.

Most of the girls said they did not talk to their friends about their bodies growing and changing, either because their friends did not show interest or got mad at them for pointing out certain things about their [the friend’s] body shape. Furthermore, they regarded talking to their friends about puberty as putting themselves in a position where the friends could hurt their feelings. One girl reported talking “about who is skinnier and who is fatter” with her friends, and that it made her feel bad “because some girls say I’m fat.” Although the girls preferred not to talk to their friends directly about how their bodies were growing and changing, they did mention comparing height and weight and talking about girls chubbier than themselves. They enjoyed other girls telling them they were pretty and skinny.

Discussion

Contrary to previous research that has often excluded fathers’ input either because of perceived lack of interest or lack of involvement in their child’s development, our findings suggest that fathers are very receptive and open to participating in research relevant to their children. Consistent with Saracho and Spodek’s (2008) description of MA fathers being either gender essentialist or gender progressive in their role, most of the fathers from our focus groups expressed sentiments that could be categorized as gender progressive, meaning they perceived their roles in both domestic and occupational activities as equal to those of their wives. Although a few emphasized the mother’s role as the primary caretaker and nurturer, several fathers saw themselves playing an integral part in their daughter’s growth and development, either directly or through their spouse. They also acknowledged themselves as equal partners in decision making regarding their daughters.

Our findings indicate that mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of their daughters’ puberty and body image were not substantially different from one another. In fact, both parents perceived their daughters to be generally healthy, despite highlighting some concerns regarding their daughter’s weight. Goodell, Pierce, Bravo, and Ferris (2008) reported similar findings among minority parents of low socioeconomic status; their findings indicated that perception of overweight was strongly influenced by family and cultural background, and did not readily define an overweight child as unhealthy. These findings, along with a recent study analyzing proximal family issues of treatment of overweight youth and their parents, underscore some barriers that need to be considered when implementing weight-loss interventions among this group (Holt et al., 2008). For instance, parents could show resistance to encouraging their children to lose weight if they do not perceive weight to be a true problem. Thus, interventions targeting weight loss in this population should focus on educating parents and children in a manner that clearly defines healthy vs. unhealthy weight.

Although few studies have examined fathers’ perceptions of their daughter’s body image, the mother–daughter relationship is readily understood to play a key role in explaining a girl’s perception of her own body image (Ogden & Steward, 2000). An example of this concept is illustrated by one of the girls in a focus group who stated that her mother made her run around the house in squares so she could lose weight; she went on to report “feeling good” when her mom reinforced her behavior by telling her that she “looks skinnier.” Such relationship dynamics could be detrimental if a daughter perceives her mother’s view and projection of her body image as mainly negative. Therefore, interventions should be aimed at encouraging mothers to build self-efficacy and project positive perceptions to their daughters regarding body image.

Even though the fathers’ knowledge of the daughters’ growth and development came primarily from the mothers, there were instances when several fathers expressed the importance of being actively involved in their daughters’ lives. Although some fathers indicated spending time with their daughters and participating in sports activities, they did express that their work schedule prohibited them from doing so as often as they would have liked. Consistent with our findings was a report about Mexican-origin parents’ involvement in their children’s lives, showing that time spent in shared activities by the mother–daughter pair was substantially greater than the father–daughter pair, that in turn was greater than the amount of time spent with boys for both parents (Updegraff, Killoren, & Thayer, 2007). Thus, it seems that fathers do interact with their daughters at the prepubertal and peripubertal stages; however, the extent and benefit of this relationship need to be explored in further research.

According to the evolutionary theory of socialization, a stressful rearing environment in childhood and the development of insecure attachments to parents promote early reproductive success in daughters, whereas delayed maturation is characterized by the opposite (Belsky et al., 2007). In line with this theory, several articles (both prospective and retrospective reports) on the effects of family context, childrearing, and pubertal timing have reported that experiences such as harsh parenting, conflicted child–parent relationships, and marital conflict predict earlier timing of pubertal development (Moffitt, Caspi, Belsky, & Silva, 1992). Consistent with theses studies, our findings provide contextual information regarding parental communication and involvement in their daughters’ lives. Both mothers and fathers seemed integrally involved in the decision-making process regarding how their daughters dressed and the influence of their friends. Furthermore, the mothers served as a key intermediary through which the fathers could learn about their daughters’ growth and development and, in turn, relay advice to their daughters indirectly. Given that parental involvement and improved parent–child communication during the adolescent years are important factors in buffering adolescents from earlier maturation and various social and emotional problems, greater effort should be made by parents to strengthen these bonds during the adolescent years (Peres et al., 2008; Vigil & Geary, 2006).

The absence of a father in the home is a stressful situation that is also associated with an earlier onset of puberty in NHW girls (Ellis, 2004; Ellis, McFadyen-Ketchum, Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1999). However, these findings are not consistent among minorities, and there remains a dearth of evidence on the levels of interaction and communication in father–daughter relationships. Some of the fathers’ interactions with their daughters (through activities such as playing soccer, reading, and going to the park) indicated the type of involvement that has been associated with reducing early biological maturation (Ellis, 2004; Ellis et al., 1999). However, this level of involvement was not reported across all of our focus groups. Many fathers expressed the desire to actively engage in activities with their daughters, but were not able to do so because of lack of time.

With regard to mothers’ recalled pubertal experiences compared to the perceived experiences of their daughters, the mothers’ recollections were mostly negative, whereas the daughters reported more positive than negative aspects of growing up. Previous reports have attributed girls’ ambivalence toward puberty to mixed messages from the media, friends, and parents, which can often contradict one another (Marvan et al., 2007). In fact, most of the girls from our focus groups had not yet experienced any negative signs of puberty, such as menstrual cramps, and most of them could only articulate their perceptions and attitudes toward puberty in very broad terms. Therefore, they emphasized the positive aspects such as the physical changes in height and weight, and expressed looking forward to growing and developing because it represented more independence from their parents. On the other hand, MA mothers reported much more negative experiences. Such discrepancies could have been because the mothers themselves had actually gone through this event or because of the general negative emphasis placed on puberty as a time of crisis. As such, it thus becomes important for families to address pubertal issues with adolescent girls at an age prior to the onset of puberty. Furthermore, more emphasis should be placed on the positive rather than the negative aspects of puberty to assure that girls are competent and able to deal with pubertal issues prior to reaching puberty.

Although our results provide important information regarding MA familial perceptions of puberty, our small sample size is a limiting factor. Furthermore, the MMC has families of low socioeconomic status (SES) and most of the parents were from Mexico; therefore, our results are exploratory in nature and cannot be extrapolated to the general Mexican American population or to those of middle or upper SES. However, we found strong evidence of parental concern regarding their daughters’ body image and pubertal growth, and showed that it was feasible to obtain quality information from fathers regarding their daughters’ growth and development.

A major strength of the study was the existing infrastructure of the MMC, which allowed recruitment of participants. Furthermore, the strategy of recruiting triads as opposed to mother–daughter pairs increased our response rates, likely because of the inclusion of the father, traditionally the familial authority figure who can influence the family’s participation. Finally, recruiting girls of 6 to 12 years helped us ensure a representation of girls at different stages of the pubertal continuum, and provided a broader base for understanding how girls of different ages perceive body image and pubertal growth.

The continuing decline in age at puberty among MA girls, compounded by the secular trend in obesity and various cultural barriers, present major issues for MA girls (Flegal et al., 2004; Siegel et al., 1999; Tremblay & Frigon, 2005). Although more in-depth studies are needed to corroborate our findings, it is evident that interventions addressing risk factors for early puberty, such as obesity, should focus on the family rather than on the individual child or the mother–daughter dyad, and should commence at an early age to obtain optimal results. This approach has proven successful for increasing knowledge of healthy behaviors and providing positive health outcomes among populations along the Texas–Mexico border (Brown & Hanis, 1995; Mier, Medina, & Ory, 2007). More effort should also be made to focus on the social and emotional consequences—as well as informational resources—regarding overweight and pubertal development. These resources need to be culturally appropriate when used to address norms and perceptions of a healthy body. Also, they should be accessible to families so that overweight in young MA girls can be effectively targeted, possibly delaying the declining trend in pubertal growth and development. These considerations should be incorporated into future studies addressing the physical, cultural, and socioeconomic dynamics of puberty in this population.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a contract from the National Institute of Health (NIH-NCI-OD/CCR: 263-MQ-515960), the Caroline W. Law Fund for Cancer Prevention, and the Dan Duncan Family Institute. Rosenie Thelus Jean was supported by a National Cancer Institute (NCI) fellowship (R25T CA57730) and Anna V. Wilkinson by an NCI grant (K07 CA12988).

Footnotes

For reprints and permission queries, please visit SAGE’s Web site at http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav.

Contributor Information

Rosenie Thelus Jean, University of Texas, M. D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, USA.

Melissa L. Bondy, University of Texas, M. D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, USA.

Anna V. Wilkinson, University of Texas, M. D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, USA.

Michele R. Forman, University of Texas, M. D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, USA.

References

- Beausang CC, Razor AG. Young Western women’s experiences of menarche and menstruation. Health Care for Women International. 2000;21(6):517–528. doi: 10.1080/07399330050130304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Steinberg LD, Houts RM, Friedman SL, DeHart G, Cauffman E, et al. Family rearing antecedents of pubertal timing. Child Development. 2007;78(4):1302–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratberg GH, Nilsen TI, Holmen TL, Vatten LJ. Sexual maturation in early adolescence and alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking in late adolescence: A prospective study of 2,129 Norwegian girls and boys. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2005;164(10):621–625. doi: 10.1007/s00431-005-1721-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Hanis CL. A community-based, culturally sensitive education and group-support intervention for Mexican Americans with NIDDM: A pilot study of efficacy. The Diabetes Educator. 1995;21(3):203–210. doi: 10.1177/014572179502100307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cachelin FM, Monreal TK, Juarez LC. Body image and size perceptions of Mexican American women. Body Image. 2006;3(1):67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Individual differences are accentuated during periods of social change: The sample case of girls at puberty. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61(1):157–168. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Sung M, Worthman C, Angold A. Pubertal maturation and the development of alcohol use and abuse. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88(Suppl 1):S50–S59. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costos D, Ackerman R, Paradis L. Recollections of menarche: Communication between mothers and daughters regarding menstruation. Sex Roles. 2002;46:49–59. [Google Scholar]

- De Assis S, Hilakivi-Clarke L. Timing of dietary estrogenic exposures and breast cancer risk. Annals of New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1089:14–35. doi: 10.1196/annals.1386.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doswell WM, Millor GK, Thompson H, Braxter B. Self-image and self-esteem in African-American pre-teen girls: Implications for mental health. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 1998;19(1):71–94. doi: 10.1080/016128498249222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doswell WM, Vandestienne G. The use of focus groups to examine pubertal concerns in preteen girls: Initial findings and implications for practice and research. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing. 1996;19(2):103–120. doi: 10.3109/01460869609038051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ. Timing of pubertal maturation in girls: An integrated life history approach. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(6):920–958. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, McFadyen-Ketchum S, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. Quality of early family relationships and individual differences in the timing of pubertal maturation in girls: A longitudinal test of an evolutionary model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77(2):387–401. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.2.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Ogden CL, Carroll MD. Prevalence and trends in overweight in Mexican-American adults and children. Nutrition Review. 2004;62(7 Pt 2):S144–S148. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodell SL, Pierce MB, Bravo CM, Ferris AM. Parental perceptions of overweight during early childhood. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18:1548–1555. doi: 10.1177/1049732308325537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber JA, Seeley JR, Brooks-Gunn J, Lewinsohn PM. Is pubertal timing associated with psychopathology in young adulthood? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(6):718–726. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000120022.14101.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Valero MA, Wilkinson AV, Forman MR, Etzel CJ, Cao Y, Barcenas CH, et al. Maternal BMI and country of birth as indicators of childhood obesity in children of Mexican origin. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(10):2512–2519. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himes JH. Examining the evidence for recent secular changes in the timing of puberty in US children in light of increases in the prevalence of obesity. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2006;254–255:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson ME, Newman B, Millikan RC. Birthweight, parental age, birth order and breast cancer risk in African-American and White women: A population-based case-control study. Breast Cancer Research. 2004;6(6):R656–R667. doi: 10.1186/bcr931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt NL, Moylan BA, Spence JC, Lenk JM, Sehn ZL, Ball GD. Treatment preferences of overweight youth and their parents in Western Canada. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18:1206–1219. doi: 10.1177/1049732308321740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta R, Brizuela-Gamino OL. Interaction of pubertal status, mood and self-esteem in adolescent girls. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 2002;47(3):217–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalman MB. Adolescent girls, single-parent fathers, and menarche. Holistic Nursing Practice. 2003;17(1):36–40. doi: 10.1097/00004650-200301000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlberg J. Secular trends in pubertal development. Hormone Research. 2002;57(Suppl 2):19–30. doi: 10.1159/000058096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lof M, Sandin S, Hilakivi-Clarke L, Weiderpass E. Birth weight in relation to endometrial and breast cancer risks in Swedish women. British Journal of Cancer. 2007;96(1):134–136. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvan ML, Vacio A, Garcia-Yanez G, Espinosa-Hernandez G. Attitudes toward menarche among Mexican preadolescents. Women & Health. 2007;46(1):7–23. doi: 10.1300/J013v46n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud PA, Suris JC, Deppen A. Gender-related psychological and behavioural correlates of pubertal timing in a national sample of Swiss adolescents. Molecular & Cellular Endocrinology. 2006;254–255:172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michels KB, Xue F. Role of birthweight in the etiology of breast cancer. International Journal of Cancer. 2006;119(9):2007–2025. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mier N, Medina AA, Ory MG. Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes: Perspectives on definitions, motivators, and programs of physical activity. Preventing Chronic Diseases. 2007;4(2):A24. Retrieved July 7, 2009, from http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2007/apr/06_0085.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Belsky J, Silva PA. Childhood experience and the onset of menarche: A test of a sociobiological model. Child Development. 1992;63(1):47–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb03594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offer D, Howard KI, Schonert KA, Ostrov E. To whom do adolescents turn for help? Differences between disturbed and nondisturbed adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30(4):623–630. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199107000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden J, Steward J. The role of the mother–daughter relationship in explaining weight concern. The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2000;28(1):78–83. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200007)28:1<78::aid-eat9>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olvera N, Suminski R, Power TG. Intergenerational perceptions of body image in Hispanics: Role of BMI, gender, and acculturation. Obesity Research. 2005;13(11):1970–1979. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan LF, Meyer-Balhburg HF, Watkins BX. Social cognitions associated with pubertal development in a sample of urban, low-income, African-American and Latina girls and mothers. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;27(4):227–235. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peres CA, Rutherford G, Borges G, Galano E, Hudes ES, Hearst N. Family structure and adolescent sexual behavior in a poor area of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42(2):177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinyerd B, Zipf WB. Puberty—Timing is everything! Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2005;20(2):75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remschmidt H. Psychosocial milestones in normal puberty and adolescence. Hormone Research. 1994;41(Suppl 2):19–29. doi: 10.1159/000183955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saracho ON, Spodek B. Demythologizing the Mexican American father. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education. 2008;7(2):79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JM, Yancey AK, Aneshensel CS, Schuler R. Body image, perceived pubertal timing, and adolescent mental health. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;25(2):155–165. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skandhan KP, Pandya AK, Skandhan S, Mehta YB. Menarche: Prior knowledge and experience. Adolescence. 1988;23(89):149–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snooks MK, Hall SK. Relationship of body size, body image, and self-esteem in African American, European American, and Mexican American middle-class women. Health Care for Women International. 2002;23(5):460–466. doi: 10.1080/073993302760190065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun SS, Schubert CM, Chumlea WC, Roche AF, Kulin HE, Lee PA, et al. National estimates of the timing of sexual maturation and racial differences among US children. Pediatrics. 2002;110(5):911–919. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.5.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun SS, Schubert CM, Liang R, Roche AF, Kulin HE, Lee PA, et al. Is sexual maturity occurring earlier among U.S. children? Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37(5):345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelman AM. Adolescent girls’ perspectives of family interactions related to menarche and sexual health. Qualitative Health Research. 2004;14:1292–1308. doi: 10.1177/1049732304268794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay L, Frigon JY. The interaction role of obesity and pubertal timing on the psychosocial adjustment of adolescent girls: Longitudinal data. International Journal of Obesity (London) 2005;29(10):1204–1211. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, Killoren SE, Thayer SM. Mexican-origin parents’ involvement in adolescent peer relationships: A pattern analytic approach. New Direction for Child and Adolescent Development. 2007;2007(116):51–65. doi: 10.1002/cad.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigil JM, Geary DC. Parenting and community background and variation in women’s life-history development. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20(4):597–604. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.4.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wattigney WA, Srinivasan SR, Chen W, Greenlund KJ, Berenson GS. Secular trend of earlier onset of menarche with increasing obesity in Black and White girls: The Bogalusa heart study. Ethnicity & Disease. 1999;9(2):181–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson AV, Spitz MR, Strom SS, Prokhorov AV, Barcenas CH, Cao Y, et al. Effects of nativity, age at migration, and acculturation on smoking among adult Houston residents of Mexican descent. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(6):1043–1049. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.055319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]