Abstract

Combining SSRIs and cognitive behavioral therapy boosts recovery rates

Practice changer

Refer adolescents with moderate to severe depression for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to improve their outcomes.1-3

Strength of recommendation

B: Two well-done randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Brent D, Emslie G, Clarke G, et al. Switching to another SSRI or to venlafaxine with or without cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with SSRI-resistant depression. The TORDIA randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:901-913.

March JS, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. The Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS): long-term effectiveness and safety outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1132-1143.

March J, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression. Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004; 292:807-820.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

Jason, a depressed 17-year-old, is brought in by his mother, who’s worried about his mood and lack of motivation. He reports that his mood has “sunk” over the last 2 months. His mother interjects that she suffers from depression herself and that she’s divorced and unable to compensate for the absence of Jason’s father. She also says that her 2 older sons, both of whom Jason is close to, recently moved out of state. Further questioning reveals that Jason has lost interest in school, sports, friends, and his part-time job; he’s pessimistic about the future and feels helpless and stuck. Jason avoids going out and spends hours on the Internet.

You consider prescribing a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), but you’re concerned about the potential suicide risk—a risk that’s already elevated for teens with major depressive disorder (MDD). Would a referral to a therapist be a safer choice? Is psychotherapy alone sufficient? What type of therapy is best?

Depressive disorders are common among adolescents and young adults, affecting nearly 1 in 4 by age 24.4 Most seek help from primary care physicians, who typically prescribe SSRIs.5 Yet only about one third of depressed teens achieve complete remission with medication alone.1 For the two thirds who continue to have depressive symptoms, the consequences can be severe. Depressive illness is associated with family conflict, smoking and substance abuse, impaired functioning in school and in relationships, and increased risk of suicide—the third leading cause of death in adolescents.6

FAST TRACK

Only about one third of depressed teens achieve complete remission with medication alone

Drugs, psychotherapy, or both?

The Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC), published in November 2007, encourage primary care physicians to take a more active role in detecting and managing adolescent depression.7 GLAD-PC and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry recommend that teens with depressive illness receive psychotherapy, either as primary treatment or in conjunction with antidepressants.7,8 Until recently, however, that recommendation lacked definitive evidence to support it.

STUDY SUMMARIES: 2 studies explore combination approach

TADS (Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study)2,3 and TORDIA (Treatment of Resistant Depression in Adolescents)1 are the only 2 randomized trials to address the role of CBT in combination with antidepressants in treating this patient population. Both show a significant benefit when CBT is added to drug therapy.

TADS: Highest improvement rates with fluoxetine and CBT

The TADS team studied 439 adolescents (ages 12 to 17 years) diagnosed with MDD. Patients were evaluated at consent, baseline, and weeks 6, 12, 18, 30, and 36. Those who were already taking antidepressants were excluded, but con-current therapy for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder was permitted.

Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of the following 12-week treatment options:

FAST TRACK

While CBT alone was not significantly better than placebo, it had a protective effect on suicidal events

Fluoxetine (10-40 mg/d)

CBT

Fluoxetine (10-40 mg/d) + CBT

Placebo

CBT consisted of 15 sessions over 12 weeks, each lasting 50 to 60 minutes. In addition to individual sessions, 2 parental sessions and 1 to 3 family sessions were included. Primary outcome measures were the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement Scale (CGI-I), which is based on a clinician’s overall assessment of the patient’s improvement; and the Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R), which is derived from parent and adolescent interviews.

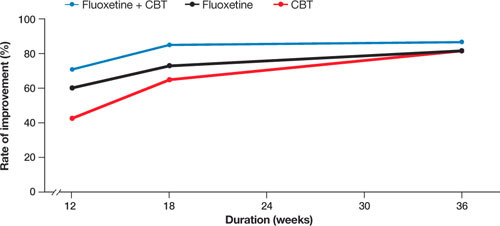

At 12 weeks, patients receiving fluoxetine and CBT demonstrated the highest rates of improvement: Seventyone percent (95% confidence interval [CI], 62%-80%) were “much” or “very much” improved, vs 60.6% (95% CI, 51%-70%) of those on fluoxetine alone. In comparison, 43.2% (95% CI, 34%-52%) of patients receiving CBT alone were much or very much improved at the 12-week mark, and only 34.8% (95% CI, 26%-44%) of those on placebo.

At 18 weeks, the medication/CBT combination remained superior to either psychotherapy or fluoxetine alone. By week 30, all 3 intervention groups converged, and at 36 weeks there was virtually no difference in outcomes (FIGURE).

FIGURE.

Fluoxetine + CBT delivers biggest improvement for adolescents with depression

CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy.

Adapted from: March JS et al. JAMA2 and March J et al. Arch Gen Psychiatry.3

CBT alone has protective effect. While CBT alone was not significantly better than placebo overall, it demonstrated a protective effect with regard to suicidal events (thoughts, threats, or attempts) compared to fluoxetine. Conversely, fluoxetine accelerated the rate of improvement in mood during the first 30 weeks of treatment.

TORDIA: How to help patients after failed treatment

Brent and colleagues studied 334 patients between the ages of 12 and 18 years who were diagnosed with MDD but did not respond to initial SSRI therapy. After a 4-week trial, they were reevaluated and tapered off the medication, then randomly assigned to 1 of the following treatment groups for 12 weeks:

Switched to a new SSRI

Switched to venlafaxine (a selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor)

Switched to a new SSRI + CBT

Switched to venlafaxine + CBT

All patients were reevaluated at week 12. Here, too, the CGI-I and CDRS-R were used for key outcome measures.

Adding CBT to a medication regimen was associated with an increased response rate; choice of antidepressant was not. The groups receiving CBT were significantly more likely to show improvement compared to those who were not undergoing CBT (54.8% [95% CI, 47%-62%] vs 40.5% [95% CI, 33%-48%], number needed to treat [NNT]=7).

WHAT’S NEW?: An alternative that speeds recovery

These 2 studies confirm the value of CBT in treating moderate to severe major depression in combination with antidepressant therapy. TADS provides evidence of both a faster recovery trajectory and lower likelihood of suicidal events with combined treatment. While TORDIA does not demonstrate a quicker recovery in terms of depressed mood or a lower rate of suicidal events, it suggests that for adolescents who do not respond to antidepressants, a referral to CBT will be more effective than a switch to a different drug.

CAVEATS: Approach was not tested with mild depression

Most adolescents who report depressive symptoms to primary care physicians either do not meet the full criteria for major depression or fall into the mild major depression range.9-11 Both of these studies enrolled only those with moderate to severe MDD.

There is evidence, however, that such an approach may not be necessary for teens with milder depression. Many earlier studies of psychotherapy alone vs control (wait list or observation) for patients with sub-threshold depressive disorders or mild major depression demonstrated that psychotherapy is effective in treating these less severe depressive states.7,12 GLAD-PC recommends a 4- to 8-week trial of active monitoring for patients with mild MDD before initiating psychotherapy or medication. 2

FAST TRACK

Telling teens that “brain changes” cause depression may alleviate the stigma and self-blame

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Patient perceptions, stigma

There are 3 major barriers to implementation: patient/parent resistance to psychotherapy, limited access to mental health specialists (lack of supply and insurance coverage limitations), and few quality standards for evidence-based psychotherapeutic approaches in community practice settings.13-15 Many adolescents have a negative view of therapy and feel stigmatized by a referral to a psychotherapist. They may also have a well-developed rationale as to why such treatment would not work for them.16

Physicians can help teens overcome these negative perceptions by giving them an opportunity to discuss their concerns—and by clarifying any misconceptions.17 The idea that “brain changes” cause depression has become popular in recent years,18 and may provide some relief to those who are troubled by the notion that they are somehow to blame for their depression.19 Presenting both antidepressant medication and psychotherapy as interventions that “change the way the brain manages mood” may be helpful in alleviating self-blame.

Consider nontraditional approaches

In areas with limited access to mental health specialists, nontraditional approaches may be needed. One such approach is to help patients arrange an initial interview with a psychotherapist, followed by telephone counseling sessions. For patients 18 years or older, MoodGym (http://moodgym.anu.edu.au/welcome) is also an option. This free Internet site incorporates features of standardized CBT and interpersonal therapy, and has demonstrated efficacy in RCTs of adults.20 For those between the ages of 14 and 21, CATCH-IT (http://catchit-public.bsd.uchicago.edu)21 is another Internet option. The site, which can be accessed by physicians and the general public, focuses on building competencies to reduce current and future depressive symptoms.

In addition, recommend self-help books. While there have been no studies of their value to adolescents, the book with the greatest evidence of efficacy in adults is “Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy,” by David D. Burns.22

FAST TRACK

Want to learn more about CBT?

For your part⋯ Before making referrals to mental health specialists, ask therapists whether they incorporate, and have been trained in, cognitive behavioral therapy. In addition, you can remain involved by asking the psychotherapist for a written treatment plan and by encouraging adolescents (and their families) to fully adhere to it.

TABLE W1.

Cognitive behavioral therapy: It’s different from “talk” therapy

| Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a broad group of therapies that differ from traditional “talk” therapy in a number of important ways. It is a scientific, evidence-based form of psychotherapy based on the belief that our thoughts, emotions, and behavior are linked and that changing the way we think and behave will positively influence our emotions. Key features of CBT include: |

| Cognitive restructuring. CBT practitioners help patients identify irrational beliefs and negative automatic thoughts and “self-talk” that result in pessimistic beliefs and negative overgeneralizations, and replace them with more realistic and positive thoughts and beliefs. |

| Behavioral activation. Strategies are developed to create pleasurable experiences to overcome the inertia and avoidance behavior associated with depression. |

| Problem-solving collaboration. CBT requires an active collaboration between therapist and patient. |

| Between-visit practice. “Homework” is an expected component of CBT, with patients advised to practice the skills they are taught and to work on specific behavioral or cognitive tasks between visits. |

| Short duration. CBT, which typically encompasses 12 to 15 sessions over a 12-week period, is of much shorter duration than traditional talk therapy |

Acknowledgments

PURLs methodology This study was selected and evaluated using FPIN’s Priority Updates from the Research Literature (PURL) Surveillance System methodology. The criteria and findings leading to the selection of this study as a PURL can be accessed at www.jfponline.com/purls.

Contributor Information

Benjamin W. Van Voorhees, Departments of Medicine, Psychiatry, and Pediatrics, The University of Chicago.

Sandy Smith, Department of Family Medicine, The University of Chicago.

Bernard Ewigman, Department of Family Medicine, The University of Chicago.

John Hickner, Department of Family Medicine, The University of Chicago.

References

- 1.Brent D, Emslie G, Clarke G, et al. Switching to another SSRI or to venlafaxine with or without cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with SSRI-resistant depression: the TORDIA randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:901–913.. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.8.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.March JS, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. The Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS): long-term effectiveness and safety outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1132–1143.. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.March J, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:807–820.. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.7.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC, Walters EE. Epidemiology of DSM-IIIR major depression and minor depression among adolescents and young adults in the National Comorbidity Survey. Depress Anxiety. 1998;7:3–14.. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6394(1998)7:1<3::aid-da2>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rushton JL, Clark SJ, Freed GL. Pediatrician and family physician prescription of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Pediatrics. 2000;105:E82.. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.6.e82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hankin BL. Adolescent depression: description, causes, and interventions. Epilepsy Behav. 2006;8:102–114.. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheung AH, Zuckerbrot RA, Jensen PS, Ghalib K, Laraque D, Stein RE. Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): II. Treatment and ongoing management. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e1313–e1326.. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birmaher B, Brent DA, Benson RS. Summary of the practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:1234–1238.. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199811000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yates P, Kramer T, Garralda E. Depressive symptoms amongst adolescent primary care attenders. Levels and associations. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:588–594.. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0792-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rushton JL, Forcier M, Schectman RM. Epidemiology of depressive symptoms in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:199–205.. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200202000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson JG, Harris ES, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The patient health questionnaire for adolescents: validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30:196–204.. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Compton SN, March JS, Brent D, Albano AM, Weersing R, Curry J. Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for anxiety and depressive disorders in children and adolescents: an evidence-based medicine review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:930–959.. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000127589.57468.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asarnow JR, Jaycox LH, Anderson M. Depression among youth in primary care models for delivering mental health services. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2002;11:477–497, viii.. doi: 10.1016/s1056-4993(02)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wisdom JP, Clarke GN, Green CA. What teens want: barriers to seeking care for depression. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2006;33:133–145.. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0036-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zuckerbrot RA, Cheung AH, Jensen PS, Stein RE, Laraque D. Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): I. Identification, assessment, and initial management. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e1299–e1312.. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Voorhees BW, Fogel J, Houston TK, Cooper LA, Wang NY, Ford DE. Beliefs and attitudes associated with the intention to not accept the diagnosis of depression among young adults. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:38–46.. doi: 10.1370/afm.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clever SL, Ford DE, Rubenstein LV, et al. Primary care patients’ involvement in decision-making is associated with improvement in depression. Med Care. 2006;44:398–405.. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000208117.15531.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lacasse JR. Consumer advertising of psychiatric medications biases the public against nonpharmacological treatment. Ethical Hum Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;7:175–179.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Voorhees BW, Cooper LA, Rost KM, et al. Primary care patients with depression are less accepting of treatment than those seen by mental health specialists. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:991–1000.. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2003.21060.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Jorm AF. Delivering interventions for depression by using the internet: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2004;328:265.. doi: 10.1136/bmj.37945.566632.EE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson L, Lewis G, Araya R, et al. Self-help books for depression: how can practitioners and patients make the right choice? Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:387–392.. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Voorhees BW, Vanderploegbooth K, Fogel J, et al. Integrative Internet-based depression prevention for adolescents: a randomized clinical trial in primary care for vulnerability and protective factors. J Can Acad Child Adoles Psychiatry. In press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]