Abstract

Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChR) are G-protein coupled receptors (M1-M5), grouped together into two functional classes, based on their G protein interaction. Although ubiquitously expressed in the CNS, the M4 protein shows highest expression in the neostriatum, cortex, and hippocampus. Electrophysiological and biochemical studies have provided evidence for overactive mAChR signaling in the fragile X knock-out (Fmr1KO) mouse model, and this has been hypothesized to contribute to the phenotypes seen in Fmr1KO mice. To address this hypothesis we used an M4 antagonist, tropicamide to reduce the activity through the M4 mAChR and investigated the behavioral response in the Fmr1KO animals. Data from the marble-burying assay has shown that tropicamide treatment resulted in a decreased number of marbles buried in the wild type (WT) and in the knockout (KO) animals. Results from the open field assay indicated that tropicamide increases activity in both the WT and KO mice. In the passive avoidance assay, tropicamide treatment resulted in the improvement of performance in both the WT and the KO animals at the lower doses (2 and 5 mg/kg) and the drug was shown to be important for the acquisition and not the consolidation process. Lastly, we observed that tropicamide causes a significant decrease in the percentage of audiogenic seizures in the Fmr1KO animals. These results suggested that pharmacological antagonism of the M4 receptor modulates select behavioral responses in the Fmr1 KO mice.

Keywords: Muscarinic receptors, fragile x syndrome, tropicamide, M4 receptors, behavior, learning and memory, audiogenic seizures

Introduction

Fragile X syndrome is caused by a tri-nucleotide repeat expansion in the 5′ untranslated region of the Fmr1 gene, resulting in transcriptional silencing of the gene and loss of FMRP. Patients with FXS present a wide range of behavioral abnormalities including hyperactivity, alterations in sensorimotor gating, cognitive impairments, and abnormalities in social behavior (Hagerman & Hagerman, 2002). The Fmr1KO mouse model of FXS (Bakker et al., 1994) recapitulates some of the phenotypes including seizures, social interaction impairments and cognitive defects (Chen & Toth, 2001; Dobkin et al., 2000; D’Hooge et al., 1996; Frankland et al. 2004; Musumeci et al., 2000; Nielsen, Derber, McClellan, & Crnic 2002; Spencer et al., 2005; Yan, Asafo-Adjei, Arnold, Brown, & Bauchwitz, 2004). A central hypothesis of FXS is based on the mGluR theory, which suggests overactive signaling through the mGluR receptors leads to various FXS phenotypes (Bear, Huber, & Warren, 2004), based on the enhanced mGluR medicated LTD in the Fmr1KO mice (Huber, Gallagher, Warren, & Bear, 2002). However, alterations in the synaptic response in the subiculum of the Fmr1KO mice in response to a muscarinic agonist, carbachol has been reported (D’Antuono, Merlo, & Avoli, 2003) suggesting the involvement of the cholinergic signaling pathway in FXS. Interestingly, Huber and colleagues showed that, the activation of muscarinic M1 receptor by carbachol, also results in enhanced M1 mediated LTD in the KO mice (Volk, Pfeiffer, Gibson, & Huber, 2007). Molecularly, muscarinic receptor activation resulted in increased expression of the downstream targets of FMRP, such as EF1a and CaMKII, indicating the presence of overactive signaling through the muscarinic receptors in the KO mice, which might contribute to phenotypes in FXS (Volk et al., 2007). Based on both electrophysiological and molecular evidence we hypothesized that blocking the activity of muscarinic receptors could potentially modulate phenotypes in Fmr1KO mice.

There are five molecularly distinct subtypes (M1-M5) of muscarinic cholinergic receptors (mAChR), which are G-protein coupled, and mediate the actions of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (Caulfield & Birdsall, 1998; Lanzafame, Christopoulo, & Mitchelson, 2003; Wess, 1996). M1 and M4 are potentially most relevant based on their high expression pattern in the neostriatum (Oki et al., 2005; Santiago & Potter, 2001) cortex and hippocampus (Adem, Jolkkonen, Bogdanovic, Islam, & Karlsson, 1997; Levey, Kitt, Simonds, Price, & Brann, 1991; Mash & Potter, 1986). Previous studies from our lab have shown that blocking M1 receptors with the antagonist dicyclomine modulates perseverative behaviors and audiogenic seizures in WT and Fmr1KO mice (Veeraragavan et al., 2011). In the present study, we determined if the M4 receptor antagonist, tropicamide, which has a 5-fold selectivity for M4 receptors (Lazareno, Buckley, & Roberts, 1990) would also alter behavioral responses of the Fmr1 KO mouse.

The current study showed that blockade of muscarinic M4 receptors modulates perseverative behavior, audiogenic seizures, locomotor activity, sensorimotor gating, and learning and memory performance in Fmr1 KO mice, making it a interesting potential therapeutic target for FXS.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Wild-type (WT) and Fmr1 knockout (KO) male littermates were used for all the behavior experiments except the studies of audiogenic seizures (AGS) where only Fmr1 KO males were used (see Veeraragavan et al., 2011). Animals were 2–3 months of age, except those used in the AGS study, which were 20–22 days of age. Mice were housed 2–5 per cage with access to food and water ad libitum and maintained in a 12 hr light: dark cycle. We used standard PCR techniques (e.g. Spencer et al., 2008) for genotyping the animals. The animal care and behavioral testing procedures were approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Animal Care and Use Committee and followed NIH guidelines.

Drug

Tropicamide (Sigma-Aldrich, T9778) was prepared in 10% cyclodextrin and the following doses (i.p.) were randomly assigned 0, 2, 5, 20 or 40 mg/kg.

Behavior testing assignment

The following behavior assays were employed to asses the effect of tropicamide, 30 min after treatment: marble-burying (MB), open-field activity (OFA), prepulse inhibition (PPI), passive avoidance (PA) and audiogenic seizures. The same group of animals were used for MB, OFA, PPI and PA with a 1–3 day interval between the tests. On a given test day each animal received a single dose of tropicamide in a randomized manner, hence an animal did not necessarily receive the same dose on multiple days. Half of the mice were first tested on MB followed by OFA, PPI and PA, and the other half were tested on OFA followed by MB, PPI and PA. We utilized this particular behavioral battery and treatment design based on our previous studies (e.g. Bouwknecht & Paylor, 2008; Veeraragavan et al., 2011).

Marble Burying

Repetitive/perseverative behavior was measured using the marble-burying assay (see Thomas et al. 2009). Testing was performed in a mouse cage (27×16.5×12.5 cm) with SANI-CHIP bedding (10 cm) and 20 marbles arranged in a 4×5 matrix. Testing was for 20 minutes and the number of marbles buried (more than 50% of its surface covered) was determined.

Open-field activity

The open-field assay (Accuscan instruments, Columbus OH) was used to measure activity and anxiety-based behavior.(as described in Veeraragavan et al., 2011). Mice were allowed to explore the arena (40 × 40 × 30 cm) for 30 min and total distance traveled and the center: total distance ratio were determined.

Prepulse Inhibition of the acoustic startle response

Prepulse inhibition (PPI) of the acoustic startle response was measured using the SR-Lab System(San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA, USA) as described (Paylor, Yuva-Paylor, Nelson, & Spencer, 2008; Veeraragavan et al., 2011). Each test session was comprised of six blocks of eight different trial types for a total of 48 trials, presented in a pseudorandom order. Percent PPI of the startle response was calculated as follows: 100−[(response to acoustic prepulse plus startle stimulus trials/startle response alone trials) × 100].

Passive Avoidance

The passive avoidance test was used to assess the effect of tropicamide on learning and memory performance in Fmr1 KO and WT mice (Marubio & Paylor, 2004; Veeraragavan et al., 2011). The apparatus consisted of a two-chambered shuttle box (Med Associates Inc., St. Albans, VT, USA); one chamber was brightly lit and the other was dark. Each animal received a single injection only on the training day 1 as described (Veeraragavan et al., 2011).

Passive avoidance to evaluate memory acquisition and memory consolidation

Since it is possible that although tropicamide was administered before training (i.e. acquisition), it may have effected the processing of the event that occurs after training (i.e. consolidation). Therefore, in order to determine if tropicamide primarily effects ‘acquisition’ or ‘consolidation’ a separate passive avoidance experiment was performed using the same protocol described above but with animals receiving tropicamide 30 min before training (pre-training) or immediately after training (post-training). The doses for this experiment were 0, 2 and 5 mg/kg.

Audiogenic seizures

Audiogenic-induced seizure susceptibility was tested by exposing the mice to to a 140db sound (SKU 49-728, RadioShack, Fort Worth, TX, USA) in a sound attenuated chamber and recording the presence of seizure-related behavior (ie wild-running, tonic/clonic seizure) as described (Veeraragavan et al. 2011)

Statistics

For most of the experiments data were analyzed using two-way ANOVAs. Follow-up comparisons were made using simple effects tests and Least Significant Difference (LSD) test. For PPI experiment, we observed an increase in prepulse inhibition with increasing prepulse intensity however we did not observe a dose effect on the 3 different prepulses and hence we analyzed the average PPI response (74, 78 and 82dB) across the 3 prepulses. For the passive avoidance acquisition and consolidation experiments, we performed a three-way ANOVA to investigate the effect of dose, genotype and treatment. For Audiogenic seizures, we used the Fisher’s exact probability test (one tailed) to analyze the percentage of seizures. The level of significance was at p < 0.05. Data were analyzed using the SPSS statistical software (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

Effects of tropicamide on stereotypic behavior

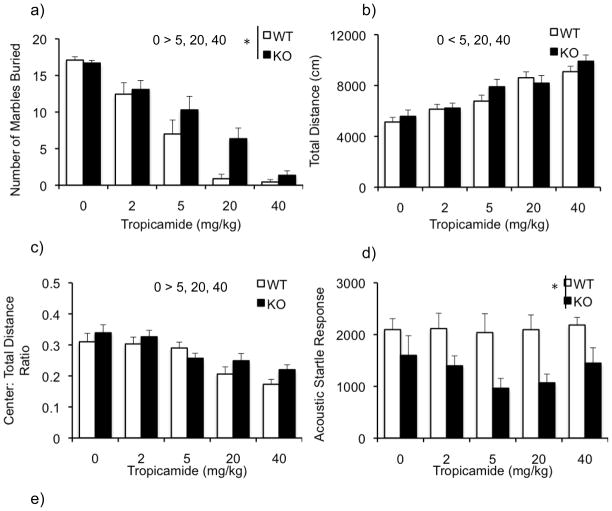

Figure 1a illustrates the number of marbles buried by WT and KO mice following tropicamide treatment. Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of genotype [F (1,89) = 6.87; p<0.05] with the KO mice burying more marbles than the WT and a significant main effect of dose [F(4,89)= 59.83, P<0.001]. Post hoc analysis revealed that the number of marbles buried at 2, 5, 20 and 40 mg/kg were significantly decreased compared to the 0 mg/kg group (p < 0.01). The dose X genotype interaction was not significant [F(4,89) = 1.97; P=0.106], suggesting that the drug has similar effects on both WT and KO mice.

Figure 1.

Effects of tropicamide on perseverative behavior, total activity, anxiety and sensorimotor gating in the WT and KO mice. Bars indicate mean ±SEM for the number of marbles buried (a), total activity as measured by total distance traveled (b), anxiety-like behavior as measured by the center: total distance ratio (c), acoustic startle response to a 120 dB startle stimulus (d) and average prepulse inhibition (e) across various doses of tropicamide. * p < 0.05 indicates significant differences between genotypes. (n=10–12/dose)

Effect of tropicamide on activity

Tropicamide caused a dose-related increase in activity (Figure 1b). ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of dose on activity [F(4,90) = 23.6; p <0.001]. Post hoc analysis showed that activity was increased at doses of 5, 20 and 40 mg/kg relative to the vehicle group. The main effect of genotype [F(1,90)= 1.8; P=0.18] and dose X genotype interaction [F(4,90)=0.791; 0.534] were not significant.

Effect of tropicamide on anxiety-like behavior

The center: total distance ratio is illustrated in figure 1c. Following tropicamide treatment, we observed a significant effect of dose [F(4,90)= 12.77; p<0.001], and the post-hoc analysis revealed that the ratio was reduced in mice that received 5, 20 and 40mg/kg compared to the controls. However, we did not observe any effect of the genotype [F(1,90)= 2.5; p=0.116] or dose X genotype interaction [F(4,90)= 1.06; p=0.381].

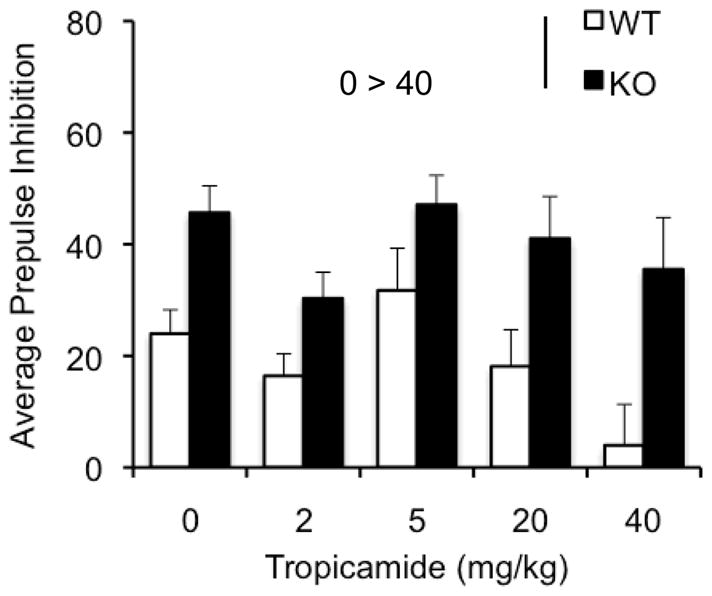

Effect of tropicamide on startle response and prepulse inhibition

Previous studies have reported a decrease in startle response and an enhanced prepulse inhibition (PPI) response in the Fmr1KO (Chen & Toth, 2001; Frankland et al., 2004; Nielson et al., 2002; Paylor et al., 2008). Consistent with the literature there was a main effect of genotype [F(1,89)= 22.89; p<0.001], indicating that overall KO mice had a decreased startle response (Figure 1d). However, we did not observe a significant main effect of the drug [F(4,89) = 0.637; p=0.638] indicating that the drug does not modulate the startle. The dose X genotype interaction was not significant either [F(4,89)= 0.402; p=0.807]. The KO mice showed enhanced PPI revealed by an overall significant effect of genotype [F(1,89)= 27.079; p< 0.001] (Figure 1e). Furthermore, we observed a significant main effect of dose [F(4,89) = 3.152; p< 0.05] with follow up analysis showing a significant decrease in PPI at a dose of 40mg/kg (p<0.05). No dose X genotype interaction was observed [F(4,89)= 0.602; p=0.662].

Effects of tropicamide on passive avoidance

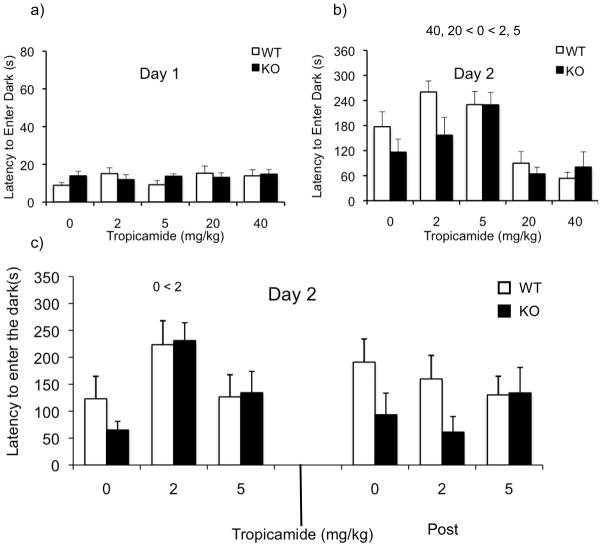

The effects of tropicamide on learning and memory was assessed using the passive avoidance assay. Analysis of day 1 latency (Figure 2a) revealed no significant main effect of genotype, dose or dose X genotype interaction (p’s > 0.05) suggesting that the drug does not alter baseline activity in this assay.

Figure 2.

Effect of tropicamide on learning and memory and audiogenic seizures in the WT and KO mice. Bars indicate mean ± SEM for the latency to enter the dark chamber on day 1 (a), and on day 2 (b). Follow up experiment investigating the latency to enter the dark following pre training and post training injection of tropicamide (c) and percentage of seizures across different doses of tropicamide. * p<0.05, indicates significant difference between WT and KO mice (n=10–12/dose)

Analysis of the latencies on day 2 (Figure 2b) showed a significant main effect of dose [F(4,90)= 11.57; p<0.001] with follow-up comparisons indicating that the latency in mice given 2 and 5 mg/kg was increased, while the latency was decreased at doses of 20 and 40 mg/kg compared to the controls (p<0.05). We observed a trend towards a significant main effect of genotype, with the KO mice showing decreased latency to enter the dark [F(1,90)= 2.891; p=0.093]. We did not observe a significant dose X genotype interaction suggesting that the drug affects both genotypes similarly [F(4,90)=1.3; p=0.251].

Effect of tropicamide on memory acquisition and consolidation using the passive avoidance assay

Figure 2c illustrates latency to enter dark on day 2 following tropicamide injection before (Pre) and after (Post) the training session. Three-way ANOVA revealed a dose X treatment interaction [F(2,86)=4.654; p< 0.05]. Simple-effects analyses revealed a significant effect of dose in the pre treatment [F(2,46)= 7.25; p<0.01], but not in the post treatment group [F(2,46)= 0.314; p=0.732]. In the pre treatment group, a dose of 2mg/kg showed a significant increase in latency compared to controls (p< 0.01). The main effect of dose [F(2,86)=1.78; p=0.174] or treatment phase [F(1,86)=0.997; p=0.321] were not significant, but there was a trend towards a significant main effect of genotype [F(1,86)=3.062; p=0.084]. Overall, these data suggest that tropicamide plays a role in the acquisition process and not in the consolidation process.

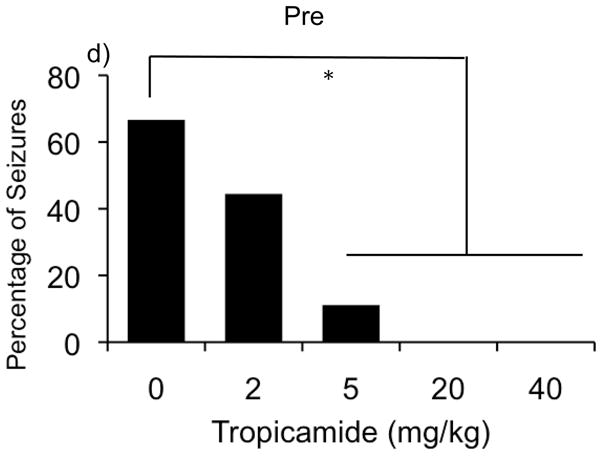

Effects of tropicamide on audiogenic seizures

Figure 2d illustrates the percentage of observed audiogenic-induced seizures across different doses of tropicamide. Fisher exact probability test (p<0.05) revealed that at the dose of 5mg/kg the drug significantly decreased percentage of observed seizures. Also, at the higher doses (20 and 40mg/kg) the drug completely abolished seizures.

Discussion

The current study provides evidence supporting the hypothesis that, modulation of the cholinergic system using an antagonist with moderate selectivity (5 fold) to the M4 receptor but also binds other muscarinic receptors includingM1, M2 and M3 receptors (Lazareno et al., 1990), alters behavioral response in the Fmr1KO mice providing a novel tool for potential therapeutic strategies for FXS. Tropicamide has been used in ophthalmic clinics (Pandit & Taylor, 2000; Smith, Grzelak, Belanger, & Morgan, 1996; Vuori, Kaila, Iisalo, & Saari, 1994). However, this is the first study investigating the role for tropicamide in a model of FXS.

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is one of the common symptoms seen in patients with FXS (Feinstien & Reiss, 1998; Hagerman & Hagerman, 2002). Interestingly, patients with OCD have been shown to have cholinergic hypersensitivity, providing evidence for the role of the cholinergic system in OCD (Lucey, Butcher, Clare, & Dinan, 1993). Marble burying is a good tool to assess stereotypic behaviors in models of OCD, and is sensitive to a number of compounds including anxiolytics and anti-depressants. (Broekkamp, Rijk, Joly-Gelouin, & Lloyd, 1986; Hedlund & Sutcliffe, 2007; Njung and Handley, 1990). Previous study from our lab has recapitulated this OCD-like phenotype in the Fmr1KO mouse model using the marble-burying assay (Spencer et al., 2011). In the current study tropicamide reduced marble burying in both WT and Fmr1 KO mice indicating a modulation of this type of repetitive behavior. Non-selective cholinergic antagonists like scopolamine and atropine have been shown to reduce marble burying in mice (Broekkamp et al., 1986), and we have shown modulation with the M1 antagonist, dicyclomine (Veeraragavan et al., 2011). Thus muscarinic antagonists reliably modulate perseverative behaviors in the mouse model of FXS.

Although non-selective antagonists like scopolamine and atropine have been shown to have sedative effects in humans, they cause hyperactivity in rodents (Alleva, Aloe, & Laviola, 1986). Genetic studies using the M4 knockout mice showed an increased basal locomotor activity (Gomeza et al., 1999). Consistent with the genetic studies, our data showed that tropicamide increases activity in KO and WT mice. Importantly, the effect of tropicamide on activity clearly suggests that its effect on marble burying is unlikely due to sedation. However the possibility that the hyperactivity might contribute to the marble burying phenotype cannot be ruled out at this point, but we have previously shown that there is no association between activity and marble burying in mice (Thomas et al., 2009). It is also possible that tropicamide caused a reduction in marble burying by reducing anxiety-like responses. Although we can not rule this possibility out, we believe that the present open-field data suggest that tropicamide does not reduce anxiety-like traits. In addition, we have previously shown that there is no correlation between anxiety measures and marble burying (Thomas et al., 2009).

Both genetics and pharmacological studies have suggested an important role for muscarinic receptors in sensorimotor gating (Jones & Shannon, 1998; Swerdlow & Geyer, 1993), yet, the M4 KO mice are reported to have no PPI phenotype but show an enhanced startle response (Thomsen, Wess, Fulton, Fink-Jensen, & Caine, 2010). However xanomeline an M1/M4 agonist has been shown to alter scopolamine-suppressed PPI in the WT but not in the M4 KO mice suggesting a role for the M4 receptors in mediating antipsychotic effect of Xanomeline (Thomsen et al., 2010). Tropicamide when given i.c.v has been shown to decrease PPI and enhance startle response in mice (Ukai, Okuda, & Mamiya, 2004). Previous studies have shown that the Fmr1KO mice display enhanced PPI and attenuated startle response (Chen & Toth, 2001; Frankland et al., 2004; Nielson et al., 2002; Paylor et al., 2008). Consistent with the literature, the Fmr1KO mice in the present study showed significantly enhanced PPI and decreased startle response compared to the WT animals, and tropicamide appeared to alter PPI, but not startle, and its effect on PPI was limited to only at the highest dose suggesting a minor role in the PPI response.

Several studies have shown that anticholinergics cause cognitive impairments in humans and in animal models, raising concerns about potential side effects in treating CNS disorders (Campbell et al., 2009). Non-selective antagonists like scopolamine and pirenzipine have been shown to impair inhibitory avoidance in mice (Caulfield, Higgins, & Straughan, 1983; Erold & Buccafusco, 1988; Ohnuki & Nomura, 1996; Worms et al., 1989). Interestingly, dicyclomine, a selective M1 antagonist has been shown to cause an impairment in the inhibitory avoidance task when given pre-training (Fornari, Moreira, & Oliveira, 2000; Soares, Fornari, & Oliveira, 2006; Veeraragavan et al., 2011) suggesting a role for the muscarinic receptors in the acquisition process. However, studies involving post-training injections of dicyclomine have provided ambiguous results, with some studies showing an impairment in the avoidance process (Ghelardini et al., 1998) and other studies showing no effect on inhibitory avoidance (Soares et al., 2006). Administration of pirenzipine directly into the hippocampus (Ferreira et al., 2003) and systemic injection of biperiden, a muscarinic antagonist (Roldan et al., 1997) impairs consolidation process, suggesting a complex cholinergic mechanism involved in memory consolidation. Our lab has shown that the M1 antagonist dicyclomine causes an impairment in the passive avoidance task in WT animals but not in the Fmr1KO animals, when administered before training session (Veeraragavan et al., 2011). The Fmr1KO animals have been shown to be impaired in inhibitory avoidance (Bakker et al., 1994; D’Hooge et al., 1996; Dobkin et al., 2000; Fisch, Hao, Bakker, & Oostra, 1999; Veeraragavan et al., 2011). In the present study the vehicle-treated Fmr1 KO mice showed a trend towards an impairment (p= 0.093) but the difference was not significant. Interestingly, pre-training injection of tropicamide caused an increase in latency to enter the dark 24 hrs after training suggesting an improvement in learning and memory performance at the lower doses of 2 and 5mg/kg but at the higher doses it caused an overall impairment.

Our follow-up study showed that the pre-training injection, but not post-training injections, caused an improvement in learning and memory indicating that M4 receptors contribute to the acquisition process for this type of passive avoidance response. Although at this point, it is unclear why we have observed a reliable pre-training enhancement in passive avoidance performance, but one possible explanation could be that the drug induced increase in acetylcholine levels. Studies have shown that in cognitively impaired aged rats, there is a decline in acetycholine release in the cortex and hippocampus (Quirion et al., 1995; Vannucchi et al., 1997) and the M2 antagonist BIBN99 has been shown to reverse the impaired acetycholine release and improves performance in Morris water maze in aged rats (Quirion et al., 1995). Another M2 antagonist methoctramine has been shown to improve procedural memory performance but not spatial performance in impaired aged rats (Lazaris et al., 2003). Also, the M1 and M4 receptors have been shown to be involved in regulating acetycholine release in the cortex and in the hippocampus (Vannucchi & Pepeu, 1995). Results from the present study showed that the M4 antagonist positively modulates learning and memory phenotype in the Fmr1KO (and WT) mice, making this drug a highly attractive candidate for therapy in FXS. However the effects of this drug might not be specific to the Fmr1KO mouse model. Since we observe effects in both the genotypes it would be interesting to investigate other types of learning and memory in the Fmr1KO mice to better elucidate the specific effects of tropicamide.

One of the most robust Fmr1KO phenotypes is the susceptibility to seizures in the presence of a loud sound stimulus (Chen & Toth 2001; Musumeci et al., 2000; Yan et al., 2004). Muscarinic agonist pilocarpine has been used to induce seizures in mouse models of temporal lobe epilepsy (Turski et al., 1984). However, muscarinic antagonists like scopolamine have been shown to not affect AGS (Bagri, Di Scala, & Sandner, 1999), and antagonists like atropine reduce AGS sensitivity in mice (Wada et al., 1971). Previously, we had shown that dicyclomine reduces AGS in a mouse model of FXS (Veeraragavan et al., 2011). In the present study we showed that tropicamide also reduces AGS at a dose of 5mg/kg, and at higher doses it completely abolishes seizures. This finding suggests that tropicamide is very potent in reducing AGS, one of the most consistent Fmr1 KO phenotypes.

Thus, we have shown that blocking the activity through the M4 receptor modulates some of the core features of FXS, supporting the hypothesis that signaling through the muscarinic receptors might modulate certain phenotypes in FXS. Tropicamide modulates perseverative behavior without causing sedation, modulates PPI, enhances performance in a passive avoidance test of learning and memory, and dramatically reduces seizures in the Fmr1KO mouse model. However, further studies are necessary to completely understand the mechanism involved in the cholinergic modulation of FXS.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Baylor Fragile X Center and the Baylor College of Medicine Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/bne

Contributor Information

Surabi Veeraragavan, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine;.

Nghiem Bui, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine;.

Jennie R. Perkins, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine;

Lisa A. Yuva-Paylor, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine;

Richard Paylor, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics and Department of Neuroscience, Baylor College of Medicine.

References

- Adem A, Jolkkonen M, Bogdanovic N, Islam A, Karlsson E. Localization of M1 muscarinic receptors in rat brain using selective muscarinic toxin-1. Brain Res Bull. 1997;44(5):597–601. doi: 10.1016/S0361-9230(97)00281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alleva E, Aloe L, Laviola G. Pretreatment of young mice with nerve growth factor enhances scopolamine-induced hyperactivity. Dev Brain Res. 1986;28(2):278–281. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(86)90032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagri A, Di Scala G, Sandner G. Myoclonic and tonic seizures elicited by microinjection of cholinergic drugs into the inferior colliculus. Therapie. 1999;54(5):589–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker CE, Verheij C, Willemsen R, van der Helm R, Oerlemans F, Vermeij M, Bygrave A, Hoogeveen AT, Oostra BA, Reyniers E, De Boulle K, D’Hooge R, Cras P, van Velzen D, Nagels G, Marti JJ, De Deyn P, Darby JK, Willems PJ. Fmr1 knockout mice: a model to study fragile X mental retardation. Cell. 1994;78:23–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bear MF, Huber KM, Warren ST. The mGluR theory of fragile X mental retardation. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27(7):370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwknecht JA, Paylor R. Pitfalls in the interpretation of genetic and pharmacological effects on anxiety-like behaviour in rodents. Behav Pharmacol. 2008;19:385–402. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32830c3658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekkamp CL, Rijk HW, Joly-Gelouin D, Lloyd KL. Major tranquillizers can be distinguished from minor tranquillizers on the basis of effects on marble burying and swim-induced grooming in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 1986;126(3):223–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell N, Boustani M, Limbil T, Ott C, Fox C, Maidment I, Schubert CC, Munger S, Fick D, Miller D, Gulati R. The cognitive impact of anticholinergics: a clinical review. Clin Interv Aging. 2009;4:225–233. doi: 10.2147/cia.s5358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield MP, Higgins GA, Straughan DW. Central administration of the muscarinic receptor subtype-selective antagonist pirenzepine selectively impairs passive avoidance learning in the mouse. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 1983;35:131–132. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1983.tb04290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield MP, Birdsall NJ. International Union of Pharmacology XVII. Classification of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50(2):279–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Toth M. Fragile X mice develop sensory hyperactivity to auditory stimuli. Neuroscience. 2001;103:1043–1050. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Antuono M, Merlo D, Avoli M. Involvement of cholinergic and gabaergic systems in the fragile X knockout mice. Neuroscience. 2003;119(1):9–13. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(03)00103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Hooge R, Nagels G, Franck F, Bakker CE, Reyniers E, Storm K, Kooy RF, Oostra BA, Willems PJ, De Deyn PP. Mildly impaired water maze performance in male Fmr1 knockout mice. Neuroscience. 1997;76:367–376. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00224-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobkin C, Rabe A, Dumas R, El Idrissi A, Haubenstock H, Brown WT. Fmr1 knockout mouse has a distinctive strain-specific learning impairment. Neuroscience. 2000;100(2):423–9. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00292-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrod K, Buccafusco JJ. An evaluation of the mechanism of scopolamine-induced impairment in two passive avoidance protocols. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1988;29:15–21. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90267-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstien C, Reiss A. Autism: The point of view from Fragile X studies. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disabilities. 1998;28:393–406. doi: 10.1023/a:1026000404855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira AR, Fürstenau L, Blanco C, Kornisiuk E, Sánchez G, Daroit D, Castro e Silva M, Cerveñansky C, Jerusalinsky D, Quillfeldt JA. Role of hippocampal M1 and M4 muscarinic receptor subtypes in memory consolidation in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;74(2):411–5. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)01007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisch GS, Hao HK, Bakker C, Oostra BA. Learning and memory in the FMR1 knockout mouse. Am J Med Genet. 1999;84:277–282. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19990528)84:3<277::aid-ajmg22>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornari RV, Moreira KM, Oliveira MG. Effects of the selective M1 muscarinic receptor antagonist dicyclomine on emotional memory. Learning and Memory. 2000;7:287–292. doi: 10.1101/lm.34900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankland PW, Wang Y, Rosner B, Shimizu T, Balleine BW, Dykens EM, Ornitz EM, Silva AJ. Sensorimotor gating abnormalities in young males with fragile X syndrome and Fmr1-knockout mice. Molecular Psychiatry. 2004;9:417–425. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghelardini C, Galeotti N, Gualtieri F, Marchese V, Bellucci C, Bartolini A. Antinociceptive and antiamnesic properties of the presynaptic cholinergic amplifier PG-9. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284:806–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomeza J, Zhang L, Kostenis E, Felder C, Bymaster F, Brodkin J, Shannon H, Xia B, Deng C, Wess J. Enhancement of D1 dopamine receptor-mediated locomotor stimulation in M(4) muscarinic acetylcholine receptor knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96(18):10483–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ. Fragile X syndrome: Diagnosis, treatment, and research. 3. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hedlund PB, Sutcliffe JG. The 5-HT7 receptor influences stereotypic behavior in a model of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neurosci Lett. 2007;414(3):247–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.12.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber KM, Gallagher SM, Warren ST, Bear MF. Altered synaptic plasticity in a mouse model of fragile X mental retardation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99(11):7746–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122205699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CK, Shannon HE. Bilateral lesions of the laterodorsal tegmental nucleus disrupt prepulse inhibition of acoustic startle reflex in rats. Schizophren Res. 1998;29:199. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzafame AA, Christopoulos A, Mitchelson F. Cellular signaling mechanisms for muscarinic acetycholine receptors. Receptors Channels. 2003;9(4):241–260. doi: 10.1080/10606820390217078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazareno S, Buckley NJ, Roberts F. Characterization of muscarinic m4 binding sites in rabbit lung, chicken heart and NG108-15 cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1990;38:805–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaris A, Cassel S, Stemmelin J, Cassel JC, Kelche C. Intrastriatal infusions of methoctramine improve memory in cognitively impaired aged rats. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24(2):379–83. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levey AI, Kitt CA, Simonds WF, Price DL, Brann MR. Identification and localization of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor proteins in brain with subtype-specific antibodies. J Neurosci. 1991;11(10):3218–26. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03218.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucey JV, Butcher G, Clare AW, Dinan TG. Elevated growth hormone responses to pyridostigmine in obsessive-compulsive disorder: evidence of cholinergic supersensitivity. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(6):961–2. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.6.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marubio LM, Paylor R. Impaired passive avoidance learning in mice lacking central neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuroscience. 2004;129(3):575–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mash DC, Potter LT. Autoradiographic localization of M1 and M2 muscarine receptors in the rat brain. Neuroscience. 1986;19(2):551–64. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90280-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musumeci SA, Bosco P, Calabrese G, Bakker C, De Sarro GB, Elia M, Ferri R, Oostra BA. Audiogenic seizures susceptibility in transgenic mice with fragile X syndrome. Epilepsia. 2000;41(1):19–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb01499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen DM, Derber WJ, McClellan DA, Crnic LS. Alterations in the auditory startle response in Fmr1 targeted mutant mouse models of fragile X syndrome. Brain Research. 2002;927:8–17. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(01)03309-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njung’e K, Handley SL. Evaluation of marble-burying behavior as a model of anxiety. Pharmacol Biochem Beha. 1991;38(1):63–7. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90590-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnuki T, Nomura Y. Effects of selective muscarinic antagonists, pirenzepine and AF-DX 116, on passive avoidance tasks in mice. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 1996;19:814–818. doi: 10.1248/bpb.19.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oki T, Takagi Y, Inagaki S, Taketo MM, Manabe T, Matsui M, Yamada S. Quantitative analysis of binding parameters of [3H]N-methylscopolamine in central nervous system of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor knockout mice. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;133:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandit RJ, Taylor R. Mydriasis and glaucoma: exploding the myth. A systematic review. Diabet Med. 2000;17(10):693–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paylor R, Yuva-Paylor LA, Nelson DL, Spencer CM. Reversal of sensorimotor gating abnormalities in Fmr1 knockout mice carrying a human Fmr1 transgene. Behav Neurosci. 2008;122(6):1371–7. doi: 10.1037/a0013047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirion R, Wilson A, Rowe W, Aubert I, Richard J, Doods H, Parent A, White N, Meaney MJ. Facilitation of acetylcholine release and cognitive performance by an M(2)-muscarinic receptor antagonist in aged memory-impaired. J Neurosci. 1995;15(2):1455–62. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01455.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roldán G, Bolaños-Badillo E, González-Sánchez H, Quirarte GL, Prado-Alcalá RA. Selective M1 muscarinic receptor antagonists disrupt memory consolidation of inhibitory avoidance in rats. Neurosci Lett. 1997;230(2):93–6. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00489-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago MP, Potter LT. Biotinylated m4-toxin demonstrates more M4 muscarinic receptor protein on direct than indirect striatal projection neurons. Brain Res. 2001;894:12–20. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03170-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RD, Grzelak ME, Belanger B, Morgan CA. The effects of tropicamide on mydriasis in young rats exhibiting a natural deficit in passive-avoidance responding. Life Sci. 1996;59(9):753–60. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(96)00361-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares JC, Fornari RV, Oliveira MG. Role of muscarinic M1 receptors in inhibitory avoidance and contextual fear conditioning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2006;86(2):188–96. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer CM, Alekseyenko O, Serysheva E, Yuva-Paylor LA, Paylor R. Altered anxiety-related and social behaviors in the Fmr1 knockout mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Genes Brain Behav. 2005;4(7):420–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2005.00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer CM, Graham DF, Yuva-Paylor LA, Nelson DL, Paylor R. Social behavior in Fmr1 knockout mice carrying a human FMR1 transgene. Behav Neurosci. 2008;122(3):710–715. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.3.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer CM, Alekseyenko O, Hamilton SM, Thomas AM, Serysheva E, Yuva-Paylor LA, Paylor R. Modifying behavioral phenotypes in Fmr1 KO mice: Genetic background differences reveal autistic-like responses. Autism Research. 2011;4(1):40–56. doi: 10.1002/aur.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Geyer MA. Prepulse inhibition of acoustic startle in rats after lesions of the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus. Behav Neurosci. 1993;107(1):104–17. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A, Burant A, Bui N, Graham D, Yuva-Paylor LA, Paylor R. Marble burying reflects a repetitive and perseverative behavior more than novelty-induced anxiety. Psychopharmacology. 2009;204(2):361–73. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1466-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen M, Wess J, Fulton BS, Fink-Jensen A, Caine SB. Modulation of prepulse inhibition through both M(1) and M (4) muscarinic receptors in mice. Psychopharmacology. 2010;208(3):401–16. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1740-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turski WA, Cavalheiro EA, Bortolotto ZA, Mello LM, Schwarz M, Turski L. Seizures produced by pilocarpine in mice: a behavioral, electroencephalographic and morphological analysis. Brain Res. 1984;321(2):237–53. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90177-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukai M, Okuda A, Mamiya T. Effects of anticholinergic drugs selective for muscarinic receptor subtypes on prepulse inhibition in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;492(2–3):183–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.03.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannucchi MG, Pepeu G. Muscarinic receptor modulation of acetylcholine release from rat cerebral cortex and hippocampus. Neurosci Lett. 1995;190:53–56. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11498-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannucchi MG, Scali C, Kopf SR, Pepeu G, Casamenti F. Selective muscarinic antagonists differentially affect in vivo acetylcholine release and memory performances of young and aged rats. Neuroscience. 1997;79(3):837–46. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeraragavan S, Bui N, Perkins JR, Yuva-Paylor LA, Carpenter RL, Paylor R. Modulation of behavioral phenotypes by a muscarinic M1 antagonist in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2276-6. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk LJ, Pfeiffer BE, Gibson JR, Huber KM. Multiple Gq-coupled receptors converge on a common protein synthesis-dependent long-term depression that is affected in fragile X syndrome mental retardation. J Neurosci. 2007;27(43):11624–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2266-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuori ML, Kaila T, Iisalo E, Saari KM. Systemic absorption and anticholinergic activity of topically applied tropicamide. J Ocul Pharmacol. 1994;10:431–437. doi: 10.1089/jop.1994.10.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada JA, Terao A, Scholtmeyer H, Trapp WG. Susceptibility to audiogenic stimuli induced by hyperbaric oxygenation and various neuroactive agents. Exp Neurol. 1971;33(1):123–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(71)90107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wess J. Molecular biology of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1996;10(1):69–99. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v10.i1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worms P, Gueudet C, Perio A, Soubrie P. Systemic injection of pirenzepine induces a deficit in passive avoidance learning in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1989;98:286–288. doi: 10.1007/BF00444707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan QJ, Asafo-Adjei PK, Arnold HM, Brown RE, Bauchwitz RP. A phenotypic and molecular characterization of the fmr1-tm1Cgr fragile X mouse. Genes, Brain and Behavior. 2004;3:337–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2004.00087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]