Abstract

The percentage of bacterial infections refractory to standard antibiotic treatments is steadily increasing. Among the most problematic hospital and community-acquired pathogens are methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA). One novel strategy proposed for treating infections of multidrug resistant bacteria is the activation of latent toxins of toxin-antitoxin (TA) protein complexes residing within bacteria; however, the prevalence and identity of TA systems in clinical isolates of MRSA and PA has not been defined. We isolated DNA from 78 MRSA and 42 PA clinical isolates and used PCR to probe for the presence of various TA loci. Our results showed that the genes for homologs of the mazEF TA system in MRSA, and the relBE and higBA TA systems in P. aeruginosa were present in 100% of the respective strains. Additionally, RT-PCR analysis revealed that these transcripts are produced in the clinical isolates. These results indicate that TA genes are prevalent and transcribed within MRSA and PA and suggest that activation of the toxin proteins could be an effective antibacterial strategy for these pathogens.

Introduction

Initially discovered on plasmids, toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems were termed “plasmid-addiction” modules to describe their role in plasmid maintenance through a post-segregational killing mechanism (Gerdes, et al., 1986, Hayes, 2003). TA systems ensure plasmid maintenance in the bacterial host population through the differential stability of the stable toxin and labile antitoxin, both encoded by the plasmid. When present, the plasmid enables the continued expression of antitoxin, which binds to and inactivates the toxin. However, if the plasmid is lost during cell division, the antitoxin protein is rapidly degraded and not replenished, thus releasing the stable toxin to kill the bacterial cell.

TA genes are also found on bacterial chromosomes, although their precise role in this setting is debated (Keren, et al., 2004, Buts, et al., 2005, Gerdes, et al., 2005, Engelberg-Kulka, et al., 2006, Szekeres, et al., 2007, Nariya & Inouye, 2008). Two of the most well studied TA systems are MazEF and RelBE encoded by the E. coli chromosome. The MazEF system in E. coli may function as an irreversible mediator of cell death under stressful conditions (Amitai, et al., 2004) or as a modulator of translation to induce a reversible state of bacteriostasis (Pedersen, et al., 2002, Christensen, et al., 2003). RelBE modulates the stringent response induced by amino acid starvation (Christensen, et al., 2001), causing global translation inhibition and leading to bacteriostasis (Pedersen, et al., 2002, Pedersen, et al., 2003). Similar to plasmid-encoded systems, chromosomal TA modules derive their intrinsic killing/growth inhibition ability from the shift in the balance towards free toxin (Christensen, et al., 2004).

Exploitation of the inherent toxicity of TA systems has been proposed as a novel antibacterial target, as activation of the latent toxin via direct TA complex disruption or some alternative mechanism would result in bacterial cell death (Engelberg-Kulka, et al., 2004, DeNap & Hergenrother, 2005, Alonso, et al., 2007, Williams & Hergenrother, 2008). However, a prerequisite for the success of this strategy is the identification of clinically important bacteria that would be susceptible to a compound that activates TA systems. Surveys of clinical isolates to determine the prevalence and identity of TA systems could support and guide the development of this strategy by establishing which TA loci are most frequently encountered and would thus serve as the best target candidates.

One such survey discovered that TA systems were frequently encoded on plasmids carried by vancomycin-resistant enterorocci (VRE) (Moritz & Hergenrother, 2007). The observation that TA systems are ubiquitous and functional on plasmids in VRE (Moritz & Hergenrother, 2007, Sletvold, et al., 2007, Halvorsen, et al., 2011) raises the possibility that other pathogenic bacteria may also harbor the genes for TA systems.

A bioinformatics survey of 126 prokaryotic genomes identified TA loci belonging to the 7 known TA gene families in the completed genomes of three S. aureus strains (Pandey & Gerdes, 2005). The genomes of all three S. aureus strains studied contained two loci belonging to the relBE gene family and one locus belonging to the mazEF gene family, which was later demonstrated to be a functional TA module in S. aureus (Fu, et al., 2007). The toxin, MazFSa, is a sequence-specific endoribonuclease that inhibits cell growth when expressed in both E. coli and S. aureus (Fu, et al., 2009, Zhu, et al., 2009). The MazEFSa system is cotranscribed with the alternative transcription factor σB under certain stress conditions (Donegan & Cheung, 2009).

Additionally, the bioinformatics survey identified three TA loci on P. aeruginosa strain PAO1, relBE, parDE, and higBA (Pandey & Gerdes, 2005). Although no additional work has been published on these TA systems, functional homologs have been described in other pathogenic bacteria, including RelBE in Streptococcus pneumoniae (Nieto, et al., 2006), Yersinia pestis (Goulard, et al., 2010) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Yang, et al., 2010); ParDE in Vibrio cholerae (Yuan, et al., 2011); and HigBA in V. cholerae (Christensen-Dalsgaard & Gerdes, 2006, Budde, et al., 2007), Proteus vulgaris (Hurley & Woychik, 2009) and Y. pestis (Goulard, et al., 2010).

While the analysis of sequenced genomes has been informative, there is no data on the prevalence and identity of TA loci in a large cadre of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and P. aeruginosa (PA) clinical isolates. In the current study, we find that mazEF, relBE, higBA, and parDE are widespread in collections of MRSA and PA clinical isolates.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains

Clinical isolates of MRSA were obtained from 3 medical centers and the Network on Antimicrobial Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus (NARSA) for a total of 78 strains. The medical centers were Carle Foundation Hospital (Urbana, IL), Memorial Medical Center (Springfield, IL), and Delnor Community Hospital (Geneva, IL). The clinical isolates of PA designated CI01–CI20 were obtained from the sputum of 20 different CF patients at Carle Foundation Hospital, as described previously (Musk, et al., 2005). The remaining 22 PA clinical isolates were a kind gift from Cubist Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Lexington, MA) and had been obtained from over eight geographically diverse clinical sites in the US.

MLVA

To assess the clonality of the clinical MRSA and PA isolates, basic molecular typing was performed by PCR-based multiple-locus variable number of tandem repeats analysis (MLVA) previously described (Sabat, et al., 2003, Vu-Thien, et al., 2007). For MRSA, a minor modification was made to the reported protocol, in that a greater amount of Taq polyermase was added to the PCR mix (5 units) and 6 μL of PCR products were analyzed in 1.8% Low-Range Ultra agarose (Biorad) for 3 hrs at 6.5 V/cm. For PA, 10 of the 15 minisatellites described by Vu-Thien and co-workers were analyzed (ms 142, ms 211, ms 212, ms 213, ms 214, ms 215, ms 216, ms 217, ms 222, ms 223) and 1 μL of PCR products was electrophoresed in 2.0% Molecular Biology Grade agarose (Fisher) at 10 V/cm. For MRSA or PA respectively, TIFF or JPEG files of the MLVA gel images were visually evaluated with BioNumerics software (Applied Maths) and a dendrogram of banding patterns was constructed using the Dice or Pearson coefficients, respectively, and the unweighted-pair group method using average linkages (UPGMA).

PCR Analysis

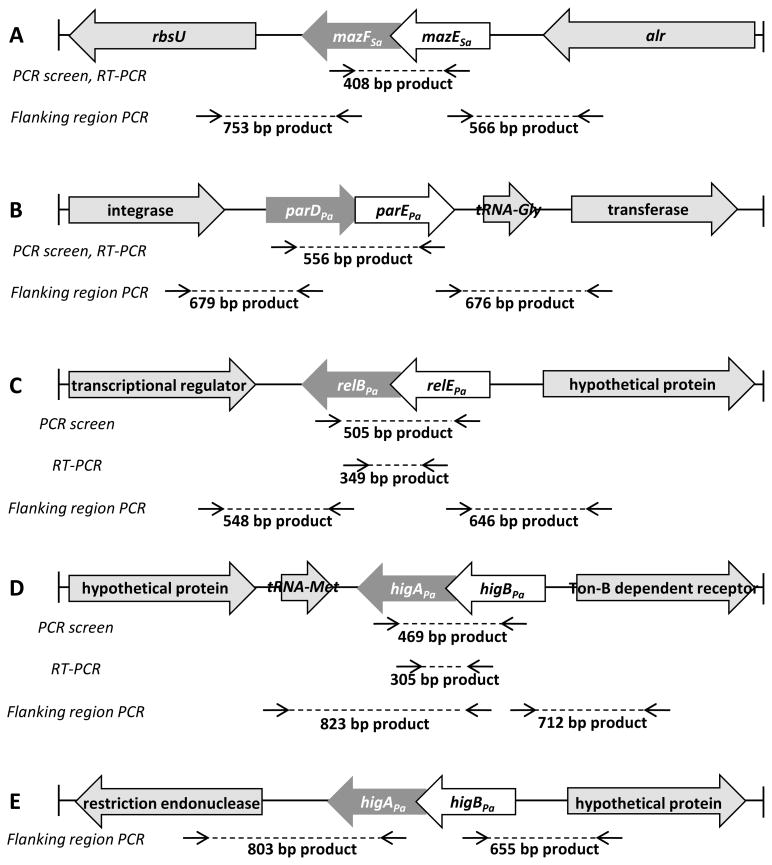

For all MRSA and PA strains, PCR amplification was performed from purified total DNA. Gene-specific internal primers were used to amplify the mazEFSa, relBEPa, parDEPa, and higBAPa TA genes and separate intergenic primers were used to amplify the upstream and dowstream flanking regions. The oligonucelotide sequences of the primers are listed in Table 1, and Figure 2 depicts the homologous region of the primers for the PCR-based screen and the flanking region primers. PCR amplification was carried out in a DNA thermal cycler (PTC-200, MJ Research, Inc.) under reaction conditions as described previously (Moritz & Hergenrother, 2007) with a lowering of the annealing temperature to 49°C for most primers. PCR amplified products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis in 1% agarose and stained with ethidium bromide.

Table 1.

Gene-specific primers used for PCR and RT-PCR analysis

| TA system | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′) | Length (nt) | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| mazEFSa | (+)ATCATCGGATAAGTACGTCAGTTT (−)AGAAGGATATTCACAAATGGCTGA |

408 | PCR, RT-PCR |

| parDEPa | (+)GCGGCTGACCTGGATTTATC (−)CCAAGCAGTAGCGGATCAATTG |

556 | PCR, RT-PCR |

| relBEPa | (+)CAGGGGGTAATTTCGACTCTG (−)ATGAGCACCGTAGTCTCGTTC |

505 | PCR |

| higBAPa | (+)CTCATGTTCGATCTGCTTGC (−)CAATGCTTCATGCGGCTAC |

469 | PCR |

| relBEPa | (+)CGCAGTACCTGGAAAGGCAGC (−)GCCTTTAACCCGAAACGGG |

349 | RT-PCR |

| higBAPa | (+)GGCCAACATAGCATCAGGATC (−)GGACGTATCAAAGTAACGCCC |

305 | RT-PCR |

| mazEFSa Up | (+)GTCTTGAACACATCTTCACGCG (−)GCGAAAATACCGACACATGTAGAG |

753 | PCR, flanking |

| mazEFSa Down | (+)GCTTCGTTCGCTAGGGAGAG (−)CTACAAGCGGGTGAGTCTGTAA |

556 | PCR, flanking |

| parDPa Up | (+)CGGTGATCTTTGCCAACACTAAG (−)CTTCCGCTCAGCATATGACTC |

679 | PCR, flanking |

| parEPa Down | (+)TGAGTCTTCTGGGGGTGCTG (−)GGAATTCCACACCATCCGC |

676 | PCR, flanking |

| relEPa Up | (+)CCGGAAAAAGCGCGAGAAAGC (−)GGGGGCTGCAATGAGCCTG |

548 | PCR, flanking |

| relBPa Down | (+)GTGCTCATTTTCTGATCAACTTCG (−)GTGACGCTCTCCGACAGCTTC |

646 | PCR, flanking |

| higAPa Up | (+)GATCCGACCCCTTCCGTCTAAACG (−)GTAGCCGCATGAAGCATTG |

823 | PCR, flanking |

| higBPa Down | (+)CAGGTGGAGAGCGCAGGTC (−)CAATTGTCCCAACGCCTCCTTCG |

712 | PCR, flanking |

| higAPa Up-PA7 | (+)GTTTGCCACGTTTGCATGCAG (−)CGCTCAGTTCTGGATGAATCTCC |

803 | PCR, flanking |

| higBPa Down-PA7 | (+)GCATCGCCGATTCCAAGTG (−)GCAACGTGTGTTCGTCACC |

655 | PCR, flanking |

(+) sense primer

(−) antisense primer

Figure 2. Locations of primary homology for primers used in PCR screen, RT-PCR and flanking region PCR.

(A) Primer sequences were based off the S. aureus COL genome. The same internal primers were used to amplify a region of mazEFSa for both the PCR-based screen and RT-PCR. Flanking mazEFSa are the genes rbsU and alr. Primers were designed to amplify the sequences from rbsU to mazFSa and from mazESa to alr. (B–D) Primer sequences were based off the P. aeruginosa PAO1 genome. (B) The same internal primers were used to amplify a region of parDEPa for both the PCR-based screen and RT-PCR. Flanking parDEPa are genes encoding an integrase, a tRNA and a transferase. Primers were designed to amplify the sequence between the integrase gene and parDPa and between parEPa and the transferase gene. (C) Separate sets of internal primers were used to amplify regions of relBEPa for the PCR-based screen and for RT-PCR. Flanking relBEPa are genes encoding a transcriptional regulator and a hypothetical protein. Primers were designed to amplify the sequence from the transcriptional regulator gene to relBPa and from relEPa to the hypothetical protein gene. (D) Separate sets of internal primers were used to amplify regions of higBAPa for the PCR-based screen and for RT-PCR. Flanking higBAPa are genes encoding a hypothetical protein and a Ton-B dependent receptor. Primers were designed to amplify the sequence from the hypothetical protein gene to higAPa and from higBPa to the Ton-B dependent receptor gene. (E) In P. aeruginosa PA7, higBAPa is flanked by genes encoding a restriction endonuclease and a hypothetical protein. Primers were designed to amplify the sequence from the restriction endonuclease gene to higAPa and from higBPa to the hypothetical protein gene.

RT-PCR Analysis

RT-PCR was performed by using the SuperScript One-Step RT-PCR with Platinum Taq kit (Invitrogen). The primers used to amplify the mazEFSa, and parDEPa sequence for RT-PCR are the same as those designed for PCR analysis, whereas RT-PCR for higBAPa and relBEPa was performed with separate specific intragenic primers designed from the P. aeruginosa PAO1 sequence. The sequences of all primers used in RT-PCR are listed in Table 1 and the homologous regions are depicted in Figure 2. The extracted total RNA (up to 40 ng) was used in RT-PCR as well as PCRs with Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) to detect DNA contamination. Reverse transcription and PCR amplification were carried out in a DNA thermal cycler (PTC-200, MJ Research, Inc.) under reaction conditions as described previously (Moritz & Hergenrother, 2007), with modifications made to the PCR annealing temperature as follows: 55°C for mazEFSa, 58°C for relBEPa, and 50.8°C for both higBAPa and parDEPa. RT-PCR amplification products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis in 1% agarose and stained with ethidium bromide.

Results

MLVA of Clinical Isolates

MRSA isolates (collected from the three medical centers and NARSA) and PA isolates (collected from Carle Foundation Hospital and from Cubist Pharmaceuticals) were analyzed by the DNA-based typing method, MLVA, to assess intra-species relatedness. Although the MLVA for the 17 NARSA strains had been previously characterized, 8 of these isolates were included in the MLVA for comparison (See SI Methods). For PA, two standard laboratory strains (PAO1 and PA14) were included for comparison.

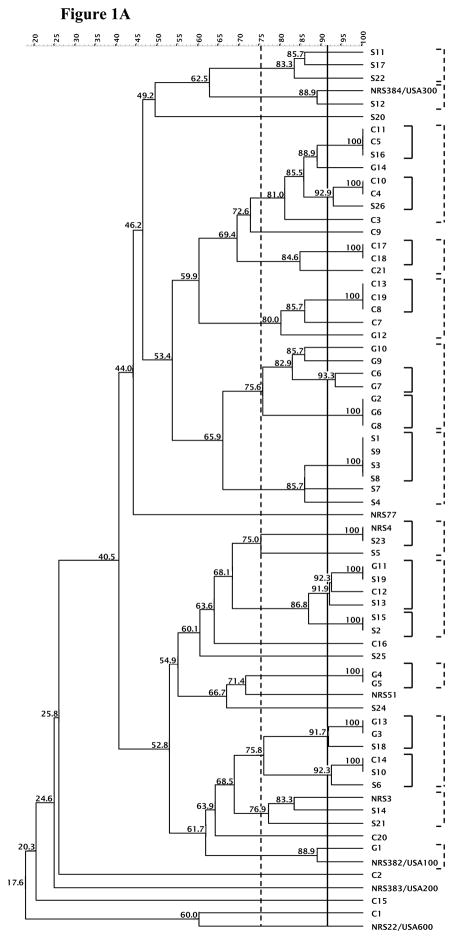

The experimental variation between duplicate experiments was determined for the MLVA profile using 5 MRSA or 5 PA isolates and applied to establish a cutoff value of 91% or 97%, respectively, for typing strains with identical DNA banding patterns. Using the 91% cutoff, 46 MLVA patterns were defined out of the 69 MRSA strains evaluated. Applying a 75% similarity value generated 13 clusters from 56 strains, excluding 13 strains from these clusters (Figure 1A). Isolates belonging to the same cluster differed by up to four bands. MLVA of the clinical S. aureus isolates using either cutoff value revealed that the majority of isolates do not belong to the same clusters as U.S. S. aureus clones (USA100, USA200, USA300, and USA600) and suggest that the isolates collected from the Illinois area are not clonal.

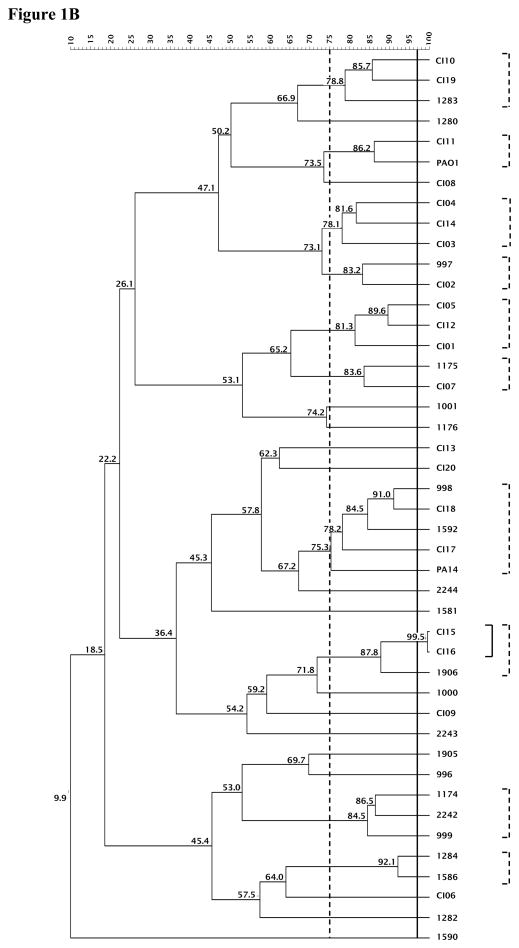

Figure 1. MLVA of the MRSAand PAclinical isolates.

The 91% or 97% clonal cutoff value and 75% similarity cutoff value are indicated by solid and dashed vertical lines, respectively for MRSA (A) and PA (B). The clusters generated are shown in corresponding solid and dashed brackets alongside the dendrogram.

For PA, using the 97% cutoff value, 43 MLVA banding patterns were formed out of the 44 strains. When a cutoff value of 75% was applied, 10 clusters were generated comprising 28 strains, and 26 MLVA banding patterns were discerned (Figure 1B). Strains that group according to these two cutoff values are in a variety of clusters, demonstrating that the isolates studied were not clonal.

Presence of TA genes

Armed with the knowledge that the collection of MRSA and PA clinical isolates were sufficiently diverse, an effort was made to define the prevalence of TA genes in the strains. For the MRSA isolates, gene-specific PCR primers were used to amplify the genes for the mazEF homolog (called mazEFSa) observed on the S. aureus COL genome (Pandey & Gerdes, 2005). The PA isolates were probed for homologs of the higBA, parDE and relBE systems identified in PA strain PAO1 (Pandey & Gerdes, 2005). The oligonucleotide sequences of all PCR primers used to amplify TA genes are listed in Table 1 and the homologous regions are represented in Figure 2.

Total DNA preparations from each of the 78 MRSA and 42 PA strains were analyzed by PCR, and results were designated positive if a distinct band was observed at the expected size on an agarose gel. The PCR screen revealed that the mazEFSa TA system was present in all MRSA isolates (78/78, 100%). For the 42 PA isolates, relBEPa (42/42, 100%) and higBAPa (42/42, 100%) were ubiquitous, whereas parDEPa (13/42, 30%) was less prevalent. Table S1 contains a complete list of all MRSA and PA isolates and the TA genes detected by PCR. Comparison of the MLVA genotypes of PA strains that carry parDEPa showed that these strains are dispersed throughout the dendrogram, indicating that there is no correlation between genome relatedness and carriage of parDEPa.

DNA sequencing was performed on ~10% of all PCR products. For the MRSA isolates, sequenced PCR products revealed strong sequence identity (95.6 – 99.5%) to the reference TA system sequence (mazEFSa alignments are shown in Figure S1). For the PA isolates, sequenced PCR products also revealed strong sequence identity (97.8 – 100%) to the reference TA system sequences (higBAPa, 99.4% average identity; parDEPa, 99.6% average identity; and relBEPa, 98.7% average identity); alignments are shown in Figures S2–4).

TA gene localization

It was next investigated whether the TA genes were located on a plasmid or the chromosome of the MRSA and PA isolates. The sequences directly upstream and downstream of the mazEFSa and relBEPa TA genes are highly conserved among the completed S. aureus and P. aeruginosa genomes in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Genome database, whereas the flanking regions of parDEPa and higBAPa are conserved in P. aeruginosa PAO1, LESB85 and UCBPP-PA14, but are different in strain PA7. Primers were designed (Table 1 and Figure 2) to amplify the sequences flanking the TA genes based on the conserved sequence in S. aureus strains and in P. aeruginosa strains PAO1 and PA7. In this experiment the presence of a PCR product would suggest chromosomal location of the TA systems.

PCR analysis revealed that in 100% (78/78) of the MRSA isolates, the regions upstream and downstream of the mazEFSa genes were amplified with the flanking region primers, suggesting a chromosomal location with sufficient homology to the S. aureus reference strains in the NCBI database. In the PA isolates, both flanking regions of the parDEPa genes in all isolates (13/13, 100%) were amplified using primers homologous to the PAO1 reference sequence. The flanking regions of nearly all relBEPa genes (41/42, 97%) were amplified, except for strain 1284, for which no flanking region could be amplified. Amplification was observed for the downstream sequence of every higBAPa loci (42/42, 100%) as well as for the region upstream of higBAPa except for in 10 strains (32/42, 76%). For these 10 strains, PCR was performed with various primers designed based on the PAO1 reference sequence, as well as primers designed to probe the upstream sequence of higBAPa observed in P. aeruginosa PA7; however, no product was amplified in any of these cases. All results from the flanking region PCR are listed in Table S2.

DNA sequencing was performed on >10% of the PCR products to confirm the identity of the amplified sequence. Sequenced PCR products revealed a strong sequence identity for the mazFSa upstream and downstream regions (91.5–98.6%) compared to the reference sequence from the S. aureus COL genome (Figure S5). The flanking region PCR products of parDEPa (92.6 – 98.2%), relBEPa (96.2 – 99.4%) and higBAPa (91.8 – 99.4%) also showed strong sequence identity to the reference P. aeruginosa PAO1 sequence (Figures S6–8).

Transcription of TA genes

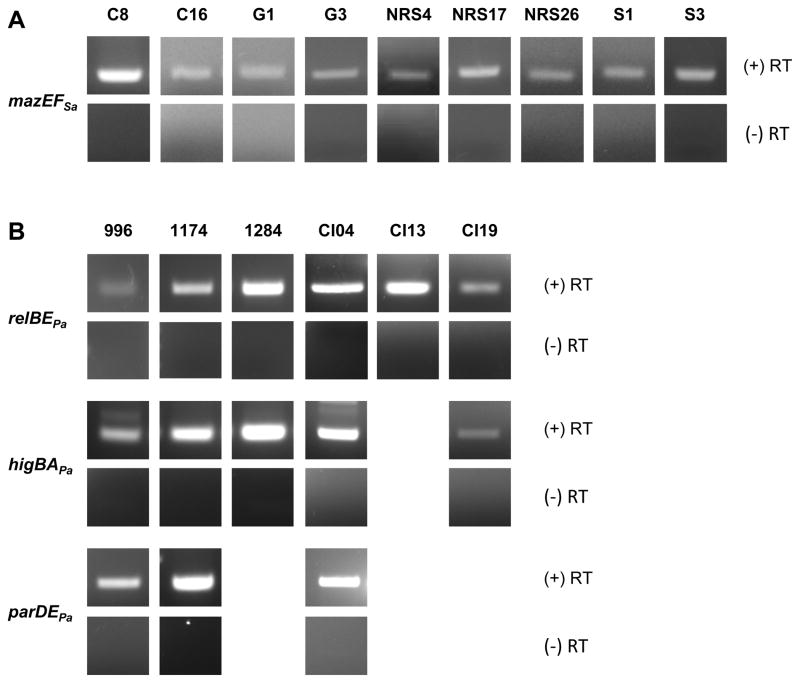

To determine if the TA systems were transcribed by the clinical isolates, RT-PCR was performed with total RNA isolated from >10% of strains shown by PCR to contain the genes for each TA system. The oligonucleotide sequences of all primers used for RT-PCR are listed in Table 1 and Figure 2 depicts the regions of homology. The mazEFSa transcript was detected from the total RNA of all nine MRSA strains probed by RT-PCR (Figure 3A). Similarly, the transcripts for relBEPa (6/6), higBAPa (5/5) and parDEPa (3/3) transcripts were detected in all PA strains probed by RT-PCR (Figure 3B). For all samples, no amplification products were observed in the absence of reverse transcriptase, confirming that the products seen by RT-PCR were due to the presence of the TA transcript in the clinical isolates and not DNA contamination (Figures 3A and B).

Figure 3. RT-PCR analysis of MRSA and P. aeruginosa clinical isolates.

RT-PCR with primers complementary to the genes encoding each TA system indicates that transcripts are produced in the clinical isolates of (A) MRSA and (B) P. aeruginosa, as shown in the (+) RT row. Controls for DNA contamination, in which the reverse transcriptase is omitted from the reaction mix, yield no product, as shown in the (−) RT row. Clinical isolates analyzed are indicated by the strain number above each column.

Discussion

Bioinformatics analyses of published prokaryotic genomes have demonstrated the pervasive nature of TA loci (Makarova, et al., 2009); however, little effort has been made to survey large collections of clinical bacterial strains for the presence and functionality of TA systems. Herein we use PCR to determine that mazEFSa is ubiquitous in a collection of MRSA clinical isolates, and higBAPa and relBEPa are ubiquitous in a collection of PA clinical isolates, whereas parDEPa is less commonly observed. This PCR method is complementary to the whole genome sequencing that has previously been used to examine the presence of TA systems in MRSA and PA, and the results reveal the value of inspecting large numbers of clinical isolates in the manner. For example, of the three sequenced PA clinical isolates that have been analyzed, PA14 does not have the genes for parDEPa, whereas PAO1 and PA7 do (Makarova, et al., 2009). However, the results presented herein show that PA clinical isolates that cluster with PA14 (via MLVA) are just as likely to have the genes for parDEPa as those PA strains that do not cluster with PA14.

Assessment of the flanking sequence of the TA systems in MRSA and PA revealed that the chromosomal location was conserved across all strains carrying mazEFSa and parDEPa, in nearly all strains for relBEPa and in the majority of strains for higBAPa. The inability to amplify the upstream sequence of higBAPa in 10 strains suggests that the upstream sequence has diverged or that the higBA loci of these 10 strains is located elsewhere; however, the conservation of the downstream sequence implies that higBAPa is chromosomally encoded.

Defining the identity of TA systems in clinical isolates satisfies the first requirement in validating TA systems as a viable antibacterial target. However, it is imperative to establish which TA systems are functional in clinical isolates. Thus RT-PCR analysis was performed to determine if the TA systems were transcribed. Importantly, it was shown by RT-PCR that mazEFSa, higBAPa, relBEPa and parDEPa were transcribed in strains that carried the genes. Collectively, the results presented herein indicate that the TA genes detected in the MRSA and PA strains reside on the chromosome and are active TA modules.

It has been suggested that activation of TA systems could be an attractive antimicrobial strategy, as the freed toxin would kill the host bacterial cell (Engelberg-Kulka, et al., 2004, DeNap & Hergenrother, 2005, Gerdes, et al., 2005, Alonso, et al., 2007, Williams & Hergenrother, 2008). While the presence of TA systems in sequenced prokaryotic genomes has been established, prior to this work the prevalence of TA systems in clinical isolates of MRSA and PA was unknown. In addition, this is the first time that the mazEFSa, higBAPa, parDEPa, and relBEPa transcripts have been shown to be produced in these bacteria, and one of the few examples of demonstrated transcription of any TA genes from a clinical isolate. Given the results of a previous study showing that TA systems are ubiquitous in VRE (Moritz & Hergenrother, 2007), and the current survey showing that TA systems are also highly prevalent and transcribed in MRSA and PA, it appears that these problematic bacterial pathogens would indeed be susceptible to TA-based antibacterial strategies. Specifically, activation of MazEFSa should be considered for MRSA, and activation of RelEPa or HigBAPa appear to be attractive strategies against Pseudomonus aeruginosa.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant 2R01-GM068385. J.J.W and E.M.H. were partially supported by a National Institutes of Health Cell and Molecular Biology Training grant T32 GM007283. E.M.D. was partially supported by the Center for Nano-CEMMS (NSF DMI-0328162) at the University of Illinois. We thank the bacterial laboratories at Carle Foundation Hospital (Urbana, IL), Memorial Medical Center (Springfield, IL), and Delnor Community Hospital (Geneva, IL) for the MRSA isolates. We also thank Cubist Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Lexington, MA) and Carle Foundation Hospital (Urbana, IL) for the P. aeruginosa isolates.

References

- 1.Alonso JC, Balsa D, Cherny I, et al. Bacterial Toxin-Antitoxin Systems as Targets for the Development of Novel Antibiotics. In: Bonomo RA, Tomalsky ME, editors. Enzyme-mediated resistance to antibiotics: mechanisms, dissemination, and prospects for inhibition. American Society for Microbiology Press; Washington DC: 2007. pp. 313–329. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amitai S, Yassin Y, Engelberg-Kulka H. MazF-mediated cell death in Escherichia coli: a point of no return. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:8295–8300. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.24.8295-8300.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Budde PP, Davis BM, Yuan J, Waldor MK. Characterization of a higBA toxin-antitoxin locus in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:491–500. doi: 10.1128/JB.00909-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buts L, Lah J, Dao-Thi MH, Wyns L, Loris R. Toxin-antitoxin modules as bacterial metabolic stress managers. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:672–679. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christensen-Dalsgaard M, Gerdes K. Two higBA loci in the Vibrio cholerae superintegron encode mRNA cleaving enzymes and can stabilize plasmids. Mol Microbiol. 2006;62:397–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christensen SK, Mikkelsen M, Pedersen K, Gerdes K. RelE, a global inhibitor of translation, is activated during nutritional stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:14328–14333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251327898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christensen SK, Pedersen K, Hansen FG, Gerdes K. Toxin-antitoxin loci as stress-response-elements: ChpAK/MazF and ChpBK cleave translated RNAs and are counteracted by tmRNA. J Mol Biol. 2003;332:809–819. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00922-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christensen SK, Maenhaut-Michel G, Mine N, Gottesman S, Gerdes K, Van Melderen L. Overproduction of the Lon protease triggers inhibition of translation in Escherichia coli: involvement of the yefM-yoeB toxin-antitoxin system. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:1705–1717. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeNap JC, Hergenrother PJ. Bacterial death comes full circle: targeting plasmid replication in drug-resistant bacteria. Org Biomol Chem. 2005;3:959–966. doi: 10.1039/b500182j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donegan NP, Cheung AL. Regulation of the mazEF toxin-antitoxin module in Staphylococcus aureus and its impact on sigB expression. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:2795–2805. doi: 10.1128/JB.01713-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engelberg-Kulka H, Amitai S, Kolodkin-Gal I, Hazan R. Bacterial programmed cell death and multicellular behavior in bacteria. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engelberg-Kulka H, Sat B, Reches M, Amitai S, Hazan R. Bacterial programmed cell death systems as targets for antibiotics. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu Z, Donegan NP, Memmi G, Cheung AL. Characterization of MazFSa, an endoribonuclease from Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:8871–8879. doi: 10.1128/JB.01272-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu Z, Tamber S, Memmi G, Donegan NP, Cheung AL. Overexpression of MazFSa in Staphylococcus aureus induces bacteriostasis by selectively targeting mRNAs for cleavage. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:2051–2059. doi: 10.1128/JB.00907-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerdes K, Rasmussen PB, Molin S. Unique type of plasmid maintenance function: postsegregational killing of plasmid-free cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:3116–3120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerdes K, Christensen SK, Lobner-Olesen A. Prokaryotic toxin-antitoxin stress response loci. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:371–382. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goulard C, Langrand S, Carniel E, Chauvaux S. The Yersinia pestis chromosome encodes active addiction toxins. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:3669–3677. doi: 10.1128/JB.00336-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halvorsen EM, Williams JJ, Bhimani AJ, Billings EA, Hergenrother PJ. Txe, an endoribonuclease of the enterococcal Axe-Txe toxin-antitoxin system, cleaves mRNA and inhibits protein synthesis. Microbiology. 2011;157:387–397. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.045492-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayes F. Toxins-antitoxins: plasmid maintenance, programmed cell death, and cell cycle arrest. Science. 2003;301:1496–1499. doi: 10.1126/science.1088157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hurley JM, Woychik NA. Bacterial toxin HigB associates with ribosomes and mediates translation-dependent mRNA cleavage at A-rich sites. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:18605–18613. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.008763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keren I, Shah D, Spoering A, Kaldalu N, Lewis K. Specialized persister cells and the mechanism of multidrug tolerance in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:8172–8180. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.24.8172-8180.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. Comprehensive comparative-genomic analysis of type 2 toxin-antitoxin systems and related mobile stress response systems in prokaryotes. Biol Direct. 2009;4:19. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-4-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moritz EM, Hergenrother PJ. Toxin-antitoxin systems are ubiquitous and plasmid-encoded in vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:311–316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601168104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Musk DJ, Banko DA, Hergenrother PJ. Iron salts perturb biofilm formation and disrupt existing biofilms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chem Biol. 2005;12:789–796. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nariya H, Inouye M. MazF, an mRNA interferase, mediates programmed cell death during multicellular Myxococcus development. Cell. 2008;132:55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nieto C, Pellicer T, Balsa D, Christensen SK, Gerdes K, Espinosa M. The chromosomal relBE2 toxin-antitoxin locus of Streptococcus pneumoniae: characterization and use of a bioluminescence resonance energy transfer assay to detect toxin-antitoxin interaction. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:1280–1296. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pandey DP, Gerdes K. Toxin-antitoxin loci are highly abundant in free-living but lost from host-associated prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:966–976. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pedersen K, Christensen SK, Gerdes K. Rapid induction and reversal of a bacteriostatic condition by controlled expression of toxins and antitoxins. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:501–510. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pedersen K, Zavialov AV, Pavlov MY, Elf J, Gerdes K, Ehrenberg M. The bacterial toxin RelE displays codon-specific cleavage of mRNAs in the ribosomal A site. Cell. 2003;112:131–140. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sabat A, Krzyszton-Russjan J, Strzalka W, et al. New method for typing Staphylococcus aureus strains: multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis of polymorphism and genetic relationships of clinical isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:1801–1804. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.4.1801-1804.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sletvold H, Johnsen PJ, Simonsen GS, Aasnaes B, Sundsfjord A, Nielsen KM. Comparative DNA analysis of two vanA plasmids from Enterococcus faecium strains isolated from poultry and a poultry farmer in Norway. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:736–739. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00557-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szekeres S, Dauti M, Wilde C, Mazel D, Rowe-Magnus DA. Chromosomal toxin-antitoxin loci can diminish large-scale genome reductions in the absence of selection. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63:1588–1605. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vu-Thien H, Corbineau G, Hormigos K, et al. Multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis for longitudinal survey of sources of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3175–3183. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00702-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams JJ, Hergenrother PJ. Exposing plasmids as the Achilles’ heel of drug-resistant bacteria. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:389–399. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang M, Gao C, Wang Y, Zhang H, He ZG. Characterization of the interaction and cross-regulation of three Mycobacterium tuberculosis RelBE modules. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10672. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuan J, Yamaichi Y, Waldor MK. The three vibrio cholerae chromosome II-encoded ParE toxins degrade chromosome I following loss of chromosome II. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:611–619. doi: 10.1128/JB.01185-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu L, Inoue K, Yoshizumi S, et al. Staphylococcus aureus MazF specifically cleaves a pentad sequence, UACAU, which is unusually abundant in the mRNA for pathogenic adhesive factor SraP. J Bacteriol. 2009 doi: 10.1128/JB.01815-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.