Abstract

Liposomes are recognized drug delivery systems with tumor-targeting capability. In addition, therapeutic or diagnostic radionuclides can be efficiently loaded into liposomes. This study investigated the feasibility of utilizing radiotherapeutic liposomes as a new post-lumpectomy radiotherapy for early-stage breast cancer by determining the locoregional retention and systemic distribution of liposomes radiolabeled with technetium-99m (99mTc) in an orthotopic MDA-MB-231 breast cancer xenograft nude rat model. To test this new brachytherapy approach, a positive surgical margin lumpectomy model was set up by surgically removing the xenograft and deliberately leaving a small tumor remnant in the surgical cavity. Neutral, anionic, and cationic surface-charged fluorescent liposomes of 100 and 400 nm diameter were manufactured and labeled with 99mTc-BMEDA. Locoregional retention and systemic distribution of 99mTc-liposomes injected into the post-lumpectomy cavity were determined using non-invasive nuclear imaging, ex vivo tissue gamma counting and fluorescent stereomicroscopic imaging. The results indicated that 99mTc-liposomes were effectively retained in the surgical cavity (average retention was 55.7 ± 24.2% of injected dose for all rats at 44 h post-injection) and also accumulated in the tumor remnant (66.9 ± 100.4%/g for all rats). The majority of cleared 99mTc was metabolized quickly and excreted into feces and urine, exerting low radiation burden on vital organs. In certain animals 99mTc-liposomes significantly accumulated in the peripheral lymph nodes, especially 100 nm liposomes with anionic surface charge. The results suggest that post-lumpectomy intracavitary administration of therapeutic radionuclides delivered by 100-nm anionic liposome carrier is a potential therapy for the simultaneous treatment of the surgical cavity and the draining lymph nodes of early-stage breast cancer.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Radioactive liposomes, Intracavitary, Brachytherapy, Locoregional retention, Lymph node

Introduction

Breast-conserving surgery (BCS) alone is associated with higher risk of locoregional recurrences. The administration of adjuvant radiotherapy (RT) after BCS significantly lowers the rate of local recurrence in patients with invasive breast cancer [1–5]. Breast-conserving therapy (BCT), consisting of BCS followed by breast RT, has become the standard therapy for most patients with early invasive breast cancer and is generally regarded as a sufficient treatment in appropriately selected patients. The classical adjuvant RT of BCT is applied to the whole breast, often with an additional boost to the tumor bed. However, early breast cancer treated by adequate surgery has few local recurrences outside the immediate vicinity of the initial tumor bed [6–8]. Recent studies of breast cancer therapy have demonstrated that accelerated partial breast irradiation (APBI) to the initial area is a promising alternative to conventional whole-breast external beam irradiation without compromising local control [9–13]. Benefits of APBI include the precise treatment of a limited volume with increased irradiation dose-to-target area, decreased time course of treatment, and less toxicity. A wide range of APBI techniques have been reported, including (1) external beam conformal irradiation [14, 15], (2) intraoperative irradiation using soft x-rays supplied by a portable spherical device [10, 16] or accelerator produced electron beam [17, 18], (3) MammoSite RTS brachytherapy using an iridium-192 (192Ir) source containing balloon catheter device [19, 20], and (4) other brachytherapy techniques using interstitial implants [21–25] or targeted radiotherapeutic agents [26]. However, APBI techniques may be limited by instrument availability. In addition, current brachytherapy mainly uses seed implants, which are sealed gamma-emitting radioactive sources that deliver relatively high radiation doses to normal breast tissue and are unable to simultaneously treat potentially involved lymph nodes (LN).

Direct locoregional administration of drugs via intratumoral and intracavitary routes for the treatment of solid tumors has been spurred in recent years by the development of novel drug carriers [27–39] and image guided interventional technologies. Locoregional administration as compared with systemic administration enables high concentration of agents at the target site, while reducing their normal tissue toxicity, thus lowering treatment-related side effects.

Drug carriers play a key role in locoregional therapy by effectively preventing the rapid clearance of drugs from the local tumor site and decreasing normal tissue burden of cleared drugs. Liposomes, spherical vesicles composed of a lipid bilayer with an interior aqueous core, are effective and versatile drug delivery systems with numerous applications in therapy and diagnostics including tumor targeting [40, 41]. Moreover, liposomes can be retained in lymph nodes [42–47]. Studies of locoregional administration of liposomes for delivery of therapeutic radionuclides have shown excellent potential for solid cancer treatment [27, 39, 48–51].

The therapeutic radionuclide, 186Re, has a sufficient half-life (3.72 days) and appropriate beta radiation energy with a penetration distance of a few millimeters in tissue (1.8 mm mean range and 5 mm maximum range) [52, 53]. The administration of an appropriate form of 186Re to the surgical area will result in a much lower radiation dose to normal breast tissue compared with other brachytherapies using sealed gamma sources. Stable encapsulation of 186Re into the liposomes has been accomplished by complexation with BMEDA ligand and taking advantage of the ammonium sulfate/pH or chemical gradient of the liposomes [54]. A portion of lymphatically absorbed 186Re-liposomes can be expected to accumulate in lymph nodes, and thus may prevent migration of tumor cells beyond the surgical site, and lead to improved tumor cell eradication. Herein, we propose a strategy of post-lumpectomy locoregional radiotherapy using liposome-carried 186Re as a partial replacement or alternative option of current RT of early-stage breast cancer. In this study, we used 99mTc-liposomes as a surrogate of 186Re-liposomes [55] in an initial investigation of the feasibility of this new brachytherapy approach in a post-lumpectomy human breast cancer xenograft model in nude rats.

Materials and methods

Breast cancer xenograft model in nude rats

Six-week-old female nude rats (rnu/rnu, Harlan, IN) were used for the breast cancer xenograft model. Each rat was anesthetized with 1–3% isoflurane in 100% oxygen and inoculated with 7 million MDA-MB-231 cells in 0.2 ml of saline into a mammary fat pad of the upper-left breast. Once the tumor was palpable, the length (l), width (w), and thickness (t) were measured with a caliper daily until surgery was performed. Tumor volume was calculated using ellipsoid volume formula, V = (π/6) × l × w × t. Tumor take rate was 80% by 3 weeks after inoculation.

Preparation of fluorescent liposomes

Liposomes (400 or 100 nm in diameter) with an ammonium sulfate/pH gradient were prepared using the lipid film rehydration and extrusion method [39]. Neutral surface-charged liposomes were comprised of DSPC/Chol/Rhod-PE/Vit E (molar ratio 54:44:0.2:2). Anionic and cationic surface-charged liposomes were comprised of DSPC/Chol/DSPG/Rhod-PE/Vit E (molar ratio, 49:44:5:0.2:2) and DSPC/Chol/DSTAP/Rhod-PE/Vit E (molar ratio 49:44:5:0.2:2), respectively.

99mTc-liposome preparation

Approximately, 1 ml of liposomes containing 55 μmol total lipids was labeled with 99mTc using our reported method [39, 56]. The 99mTc labeled 100 nm liposomes were purified by column separation with a PD-10 gel column. The 99mTc-400 nm liposomes were purified by centrifugation at 8,000 g for 5 min followed by resuspension of the pellets in PBS, pH 7.4. The labeling efficiencies of these liposomes were 42.1–77.0%.

Intracavitary injection of 99mTc-liposomes after surgery

Twenty-five rats bearing 0.8–3.1 cm3 tumors were divided into six groups (five rats for 400 nm neutral liposomes and four rats for each of other liposome groups), so that the average tumor volume and tumor volume range were similar. Surgeries were conducted in a sterile environment and the majority of tumor was dissected, while a small volume of tumor remnant (about 0.05 cm3) was deliberately left in the bottom of the surgical cavity as a positive tumor margin. Then saline was used to wash the cavity and the cutaneous incision was sutured. Surgical adhesive (Vetbond™, 3 M) was applied as a supplement to seal the incision. One day after surgery, the rats were intracavitarily injected with 0.5 ml of freshly labeled 99mTc-liposomes (66.6–159.1 MBq of 99mTc, 25.2–34.4 mg of total lipids/kg body weight). The syringe with 25G 5/8 in. needle was slowly and gently withdrawn to avoid drug leakage. Surgical adhesive was used to close the injection site if necessary and gauze was used to gently adsorb any leakage from the injection site.

Intracavitary retention and systemic biodistribution of injected 99mTc-liposomes

Planar gamma camera, pinhole-collimator SPECT, and co-registered CT images were acquired for all groups with a micro SPECT/CT scanner (XSPECT, Gamma Media, Northridge, CA). Planar gamma camera images were acquired at baseline, 1, 2, 4, 20, and 44 h. A standard 99mTc source was located beside the rat and within the field of view of the scanner for image quantification. The pinhole collimator SPECT images focused on the surgical cavity were collected at 2 and 20 h, respectively, immediately followed by co-registered CT imaging with the geometric position of anaesthetized rat unchanged.

Blood samples were collected through cardiac puncture after nuclear imaging at 44 h, and the rat was euthanized immediately. The intracavitary fluid was extracted and 1 ml of saline was gently injected into the cavity and then extracted and combined with the intracavitary fluid sample. Then the rats were dissected and DsRed fluorescent images of the opened surgical cavity and surrounding area were obtained using a fluorescence stereomicroscope (Leica MZ16 FA). Then skin above the cavity, tumor remnant in the cavity, muscle under the cavity and major normal organs were collected and counted along with the 99mTc standard sample for radioactivity measurement.

Results

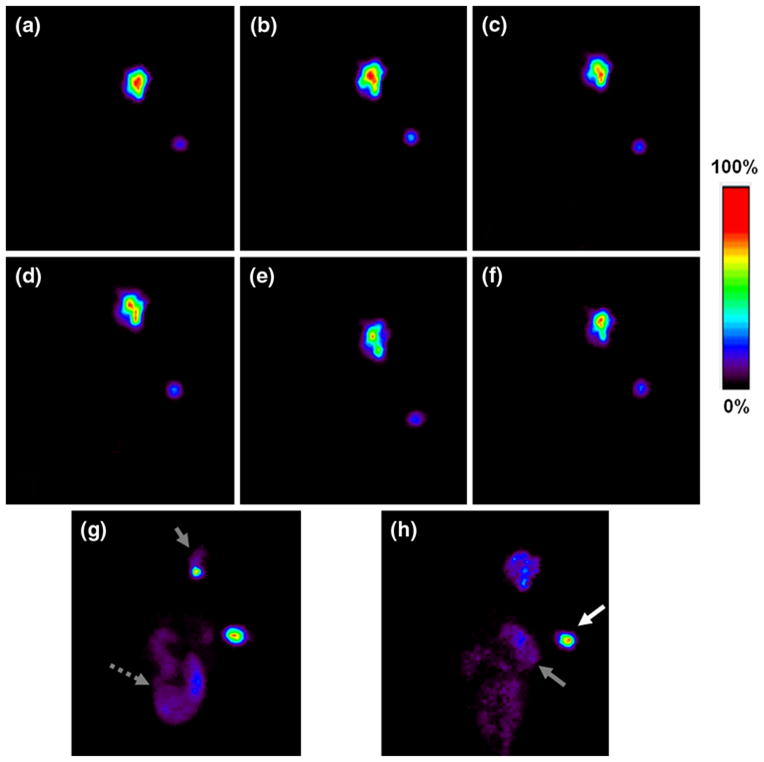

Intracavitary retention of 99mTc-liposomes by planar and micro SPECT/CT imaging

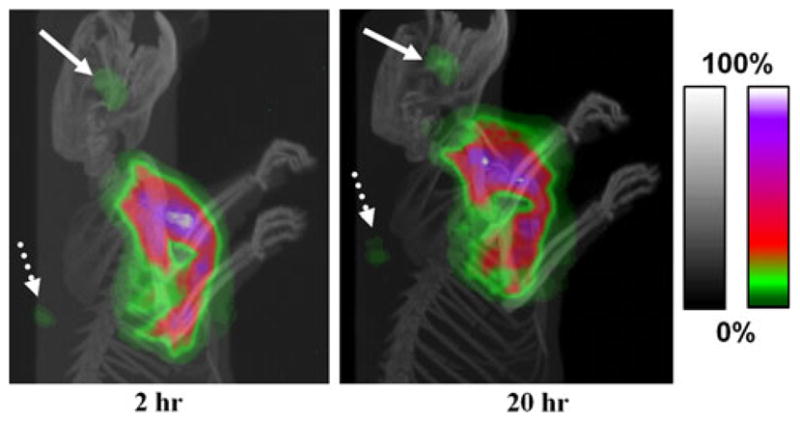

Planar gamma camera images clearly showed that in most rats, a majority of radioactivity in the body was retained in the cavity area and the cavity margin over the 44 h study (Fig. 1). The anatomic distribution of radioactivity retained in the cavity and the detectable peripheral superficial cervical lymph nodes (SCLN) or axillary lymph nodes (ALN) was evident in the SPECT and micro-CT fused projection images (Fig. 2). Quantitative locoregional retention of injected radioactivity was derived from region of interest analysis of the planar images of the rats and normalized to the 99mTc standard. The average locoregional retention rate of injected dose (ID) at 44 h post-injection was 50.7 ± 24.2% for all rats. For several rats, distributed in different groups, a significant amount of radioactivity was abruptly cleared from the cavity at some time points. Moreover, the cleared radioactivity was metabolized rapidly and mainly excreted into the large intestines (Fig. 1g–h).

Fig. 1.

Planar gamma camera images of rats intracavitarily injected with 99mTc-liposomes. Images (a–f) show representative images of a rat with low clearance of radioactivity after injection of the 100-nm anionic liposomes acquired at baseline, 1, 2, 4, 20, and 44 h post-injection, respectively. Image g shows a rat with a large amount of radioactivity excreted into large intestines, as a representative of three rats of 400-nm anionic liposome group acquired at 1–4 h, one rat of 100-nm neutral liposome group acquired at 2–4 h, and two rats of 400-nm neutral liposome group at 20 h. h Shows the image of a rat with remarkable radioactivity located in stomach and large intestines at 44 h, representing one rat of 100-nm anionic liposome group and one rat of 100-nm cationic liposome group, whose thoracic wall was seriously invaded by the tumor. Grey arrow head surgical cavity, white solid arrow 99mTc- standard, grey short dashed arrow large intestines, grey solid arrow stomach

Fig. 2.

Projection images of fused microSPECT/CT images of a rat acquired at 2 and 20 h post-intracavitary injection of 99mTc-liposomes. The gray and color scale bars show the pixel values from 0 to maximum expressed with an arbitrary 100%, for the CT and SPECT images, respectively. The pixel values beyond the color range of the map are shown in white. There was apparent accumulation of radioactivity in the cervical (white solid arrow) and axillary lymph nodes (white dotted arrow) draining from the surgical area. Most radioactivity was retained locally throughout the surgical cavity area

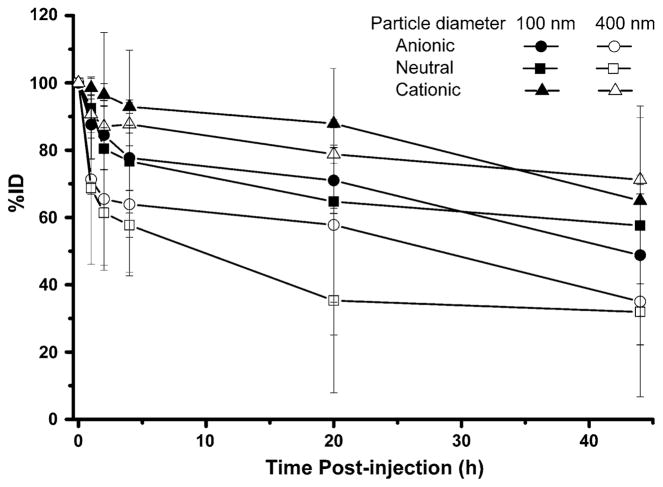

Intracavitary radioactivities of rats injected with 99mTc-anionic liposomes had a faster clearance during the first 4 h followed by a decreased clearance during the remainder of the 44 h study (Fig. 3). For the 100 nm liposome group, the intracavitary %ID was 77.7 ± 9.7% (74.2–84.0%) at 4 h and 48.8 ± 18.2% (12.4–58.5%) at 44 h, while that of the 400 nm liposome group was 35.0 ± 12.8% (17.6–46.7%) at 44 h. One rat in the 100 nm anionic liposome group had abnormally low intracavitary retention (12.4%ID) at 44 h, which was accompanied with a relatively high radioactivity accumulation in the opacified large intestine (11.3%) and stomach (10.2%) (Fig. 1h). The high degree of clearance may be related to the increased invasiveness of the tumor which led to enhanced lymphatic or vascular drainage in the surgical area.

Fig. 3.

Percent injected dose (%ID) of 99mTc-liposomes retained in the surgical cavity of rats at various time points after intracavitary injection

For the 99mTc-400 nm neutral liposome group, the intracavitary radioactivity also decreased relatively rapidly during the first 4 h post-injection with an average retention of 57.7 ± 3.6%, which slowly decreased to 46.2–55.4% at 44 h for three rats. In contrast, for the other two rats in this group, the intracavitary radioactivity continued to decrease to about 5% at 20 h, which remained unchanged at 44 h.

Three of 4 rats in 100 nm neutral liposome group had high (≥69%ID) intracavitary retention of radioactivity during the 44 h study, whereas one rat displayed a rapid clearance of 71.5% of injected dose within 2 h post-injection. A large blood vessel extending from the residual tumor in cavity to the intercostal tissue was visualized during dissection and could have led to the faster clearance rate.

The clearance of 99mTc from the injection site was slow for both 99mTc-400 nm and -100 nm cationic liposomes (Fig. 3). The injected dose remaining in the cavity over the 44 h study period averaged 71.2 ± 1.4 and 65.0 ±24.7%, respectively.

Systemic organ distribution of 99mTc-liposomes by planar imaging

Besides the surgical cavity, the systemic organ distribution of 99mTc-liposomes can also be derived from the planar images (Fig. 1). Liver was the only major organ recognizable during the entire monitoring period, but still represented a low activity compared with the cavity activity. For several rats, small areas of high radioactivity denoting lymph nodes surrounding the cavity were evident in the planar images, and displayed more clearly by the micro SPECT/CT. The highest %ID in liver at any time point was 4.5 ± 3.5% from the 400 nm anionic liposome group. Kidney, spleen, and large intestine of some rats could be delineated in the images at some time points. The highest measured values of %ID in the kidneys and the spleen for all rats were 2.7 and 2.8%, respectively. The cleared radioactivity, when significant and observable, was mainly excreted through the intestines.

Radioactivity accumulation in peripheral lymph nodes, including SCLN or ALN, in the drainage route of the surgical cavity were visible in the planar images for three rats administered 100 nm anionic liposomes, and validated by micro SPECT/CT imaging and ex vivo tissue counting. The %ID in these lymph nodes showed the quick accumulation of radioactivity in the first 1–4 h and the subsequent slow change.

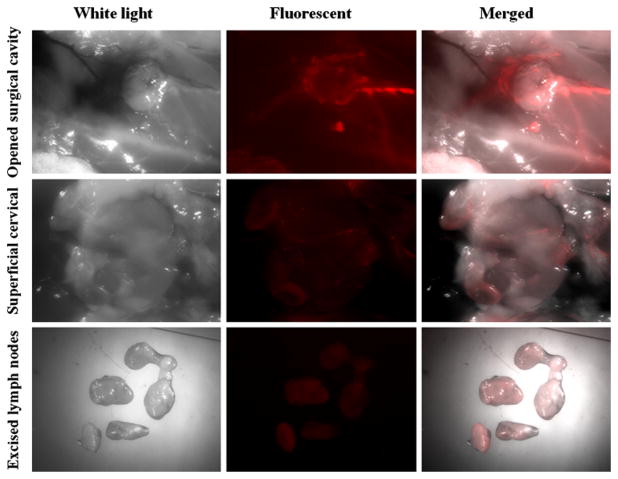

Locoregional retention of 99mTc-liposomes by fluorescence stereomicroscopic imaging

The intracavitary fluid, if present, showed strong DsRed fluorescence, contributed by Rhod-PE, the fluorescent lipid component of the liposomes. After the fluid was extracted, the fluorescent images showed that Rhod-PE was unevenly distributed on the intracavitary tissue surface as well as on the tumor remnant surface, implying the inhomogeneous accumulation of 99mTc-liposomes in the cavity (Fig. 4). The locally injected liposomes post-lumpectomy could also be cleared via lymphatic absorption, which was clearly visualized by the DsRed fluorescence localized in SCLN, ALN and lateral thoracic lymph node (LTLN) near the cavity (Fig. 4). However, the relative intensity of fluores-cence among the different lymph nodes varied significantly among different rats.

Fig. 4.

Fluorescent stereomicroscopic images acquired at 44 h after intracavitary injection of 99mTc-fluorescent liposomes. The distribution of DsRed fluorescence (excitation: 545/30 nm; emission: 620/60 nm) on the muscle and tumor surface inside the surgical cavity was inhomogeneous (upper panel). The fluorescence showed the lymphatic drainage into cervical lymph nodes (middle panel); ex vivo fluorescence of excised lymph nodes revealed the accumulation of cleared liposomes by the lymph nodes surrounding the surgical cavity (bottom panel)

Biodistribution of 99mTc-liposomes by gamma counting

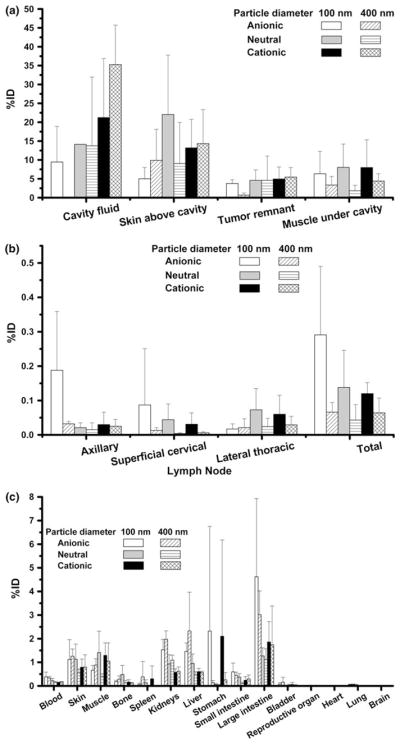

The values of %ID and %ID per gram of organ tissue (%ID/g) in the collected biological samples were calculated based on the radioactivity of each sample and the injected 99mTc-liposomes and depicted in Figs. 5 and 6, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Percent injected dose (%ID) of 99mTc-liposomes per organ/tissue at 44 h post-injection for a samples from surgical cavity, b lymph nodes surrounding surgical cavity, and c other major organs

Fig. 6.

Percent injected dose (%ID) of 99mTc-liposomes per gram of organ/tissue at 44 h post-injection for a samples from surgical cavity having highest %ID/g, b lymph nodes surrounding cavity and organs having lower %ID/g, and c other major organs having the lowest level of %ID/g

The majority of radioactivity cleared from the cavity was excreted into feces and urine after 44 h metabolism. The average %ID in feces was highest in 400 nm anionic liposome group (32.0 ± 18.0%) and lowest in 400 nm cationic group (7.1 ± 2.6%). The degree of %ID in feces corresponded with that of cleared radioactivity, which was mainly excreted into large intestine. Average %ID in urine ranged from 5.7–15.5% for the different groups.

The two anionic liposome and 100 nm neutral liposome groups had only a minimal amount of cavity fluid at 44 h post-injection, whereas the cationic liposome groups and 400 nm neutral liposome group generally had significant activity (9.5–46.4%ID) in the cavity fluid. The %ID values of tumor remnant for all the other groups were similar (3.8 ± 1.0–5.5 ± 2.5%), and higher than that of the 400 nm anionic group (1.0 ± 0.1%). For all formulations, the %ID in muscle located immediately under the cavity injected with 100 nm liposomes was higher than for all 400 nm liposome formulations (7.5 ± 6.0% vs. 3.1 ± 2.0%). All 99mTc-liposomes were attached to the skin above cavity at a significant amount (5.0–22.1%ID).

The highest values of %ID/g were in the samples of surgical cavity area, including skin above cavity, muscle under cavity and tumor remnant (Fig. 6a). For the %ID/g of tumor remnant (66.9 ± 100.4%/g for all rats), there was no statistical difference among all groups. The %ID/g of muscle under cavity showed an increasing trend with decreasing sizes of the same liposome formulation.

The values of %ID in the peripheral lymph nodes varied considerably among the rats, in a range from nearly undetectable to the highest value of 0.41%ID. The 100 nm anionic liposome group had the highest average %ID in the SCLN and ALN (0.09 ± 0.16 and 0.19 ± 0.17%), and the 100 nm neutral liposome group had the highest average %ID in the LTLN (0.07 ± 0.06%). The number of rats with %ID greater than 0.1%ID was 4, 2, and 1 attributed to the 100 nm anionic, neutral and cationic liposome groups, respectively.

Most of the %ID/g values for lymph nodes, varying from 0.01 to 7.65%ID/g for all rats, were much higher than that of normal muscle (2.2–687 folds), indicating liposome clearance occurred via the lymphatic route. The average %ID/g values of the same lymph node for the 100 nm liposome group were higher than that of the 400 nm liposome group (Fig. 6b), but lacked statistical significance. The %ID/g values of SCLN and ALN of rats, who had abrupt clearance of radioactivity from the cavity, were relatively smaller than other rats within the same group.

The highest %ID in kidneys was 1.26 ±0.26% for the 400 nm anionic liposome group. The %ID values in the spleen of all rats were no more than 1.36%. The %ID values in the stomach were <1% for all rats except one rat in the 400 nm anionic liposome group (9.0%ID) and one rat in the 100 nm cationic group (3.2%ID) mentioned in Fig. 1h. Only a slight amount of radioactivity (<0.2%ID) was found in heart, lung, brain, bladder, and reproductive organs. Figure 6 shows that the %ID/g values of the major normal organs were at a low level and much lower than the samples from the cavity area.

Discussion

Post-lumpectomy locoregional radiation therapy is generally the standard treatment of early stage breast cancer patients. However, this conventional treatment presents some limitations and the development of alternative modalities is needed. Intracavitary injection of therapeutic drugs can deliver a high drug concentration to the residual positive margin which may improve tumor response and reduce systemic toxicity. However, the feasibility of this superior concept to early stage breast cancer treatment has yet to be proven. Obviously, these investigations can only be realized if an appropriate drug carrier is available to effectively prevent the rapid clearance of drugs from tumor target, and therefore decrease the burden of cleared drug in normal tissue.

The intracavitary administration of 186Re-liposomes [54] may afford a potential brachytherapy approach for treating residual disease of early stage breast cancer with both lower toxicity and improved local recurrence and systemic metastasis control. Herein, we investigated 99mTc-labeled fluorescent liposomes as a surrogate for 186Re-liposomes to better understand the in vivo behavior of the liposomes after post-lumpectomy intracavitary injection in a breast cancer xenograft rat model with positive surgical margin. Non-invasive nuclear imaging and ex vivo tissue counting illustrated the dynamic and quantitative change in the intracavitary retention and systemic distribution of the 99mTc-liposomes. Lymphatic uptake and lymph node targeting of these fluorescent liposomes were also validated with fluorescent stereomicroscopic imaging.

Our study confirmed the high locoregional retention of 99mTc-liposomes, with 50.7 ± 24.4%ID retained in the surgical cavity area at 44 h post-injection (Fig. 3). The 100 nm neutral and anionic liposomes had higher local retention than the 400 nm liposomes, which had relatively faster clearance in 4 h. The intracavitary retention of cationic lipsomes was higher than the neutral and anionic liposomes, but the %ID in the cavity fluid was also higher. This phenomenon may be attributed to the binding interaction of cationic liposomes with proteins of the cavity fluid [57, 58]. The lack of statistical significance of intracavitary retention may be related to the limitation of animal number and the minor change in liposome surface zeta potential as the formulation was comprised of only 5% charged lipid. A high percentage of radioactivity dose was associated with the tumor remnant (66.9 ± 100.4%ID/g at 44 h). The radioactivity portion attached to the skin above cavity was significant, yet estimated to only cause a potential problem of skin toxicity in rat models, and not likely to prevent use in human subjects due to the significantly thicker layers of subcutaneous fat and skin in humans.

Radioactive liposomes were also taken up by the peripheral lymph nodes draining the surgical cavity. Particle size, surface characteristics, and in vivo liposome stability are important factors influencing the lymphatic delivery of liposomes and their lymph node targeting [42, 59, 60]. The intra-group variation of %ID in the lymph nodes reflects the individual-specific status of lymphatic and intravascular circulation around the surgical cavity post-lumpectomy. Overall, the 100 nm liposomes had higher lymph node uptake than the 400 nm liposomes. Moreover, the 100 nm anionic 99mTc-liposomes had the highest lymph node accumulation of all liposome groups tested. The migration of tumor cells to regional lymphatics and lymph nodes is a universal step of tumor metastases and progression [61]. Accompanying the effective locoregional retention, this simultaneous delivery of the radiotherapeutic liposomes from the surgical cavity post-lumpectomy is anticipated to share the same migration pathway as tumor cells that have dissociated from the primary tumor, and thus has potential for enhanced therapeutic effectiveness.

A reason for the abrupt change in clearance observed in several rats may be related to the differing physiological status of the surgical site caused by different primary tumor location and size, tumor physiologic status, surgical extent and subsequent inflammation, and wound healing. Some rats had a leakier surgical cavity attributed to the presence of a more invasive tumor or higher interstitial pressure which led to an enhanced lymphatic or intravascular drainage of the liposomes. The pathway of cleared radioactivity could not be observed in detail due to the intermittent acquisition of planar images; however, the rapid excretion of cleared radioactivity into the large intestines suggests a rapid metabolism of 99mTc-liposomes by liver and the low systemic toxicity of intracavitary administration of radiotherapeutic liposomes post-lumpectomy.

The method of radionuclide encapsulation of liposomes applied in this study takes advantage of ammonium sulfate/pH gradient, which has also been commonly used for entrapment of chemotherapeutic drugs. Therefore, this radiolabeling method enables the combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy using the same particles [54]. Furthermore, this method allows the surface of liposomes to be modified with active tumor targeting molecules, such as anti-angiogenesis antibodies for development of active targeted therapy. In conclusion, the intracavitary administration of 100 nm anionic liposome-carrying radiotherapeutic agents is a potentially convenient alternative modality of post-lumpectomy radiotherapy for early stage breast cancer treatment.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Susan G. Komen for the Cure® research grant, BCTR0707169 and partly supported by NIH/NCI grant, R01 CA131039. Fluorescent stereo-microscopic images were generated in the Core Optical Imaging Facility which was supported by UTHSCSA, NIH-NCI P30 CA54174 (San Antonio Cancer Institute), NIH-NIA P30 AG013319 (Nathan Shock Center), and (NIH-NIA P01AG19316).

Abbreviations

- %ID/g

Percentage of injected dose per gram

- ALN

Axillary lymph nodes

- APBI

Accelerated partial breast irradiation

- BCS

Breast-conserving surgery

- BCT

Breast-conserving therapy

- BMEDA

N,N-bis(2-mercaptoethyl)-N′,N′-diethyl-ethylenediamine

- Chol

Cholesterol

- CT

Computed tomography

- DOPC

1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- DSPC

1,2-Distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- DSPG

1,2-Distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-[phospho-rac-(1-glycerol)] sodium salt

- DSTAP

1,2-Distearoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane chloride salt

- ID

Injected dose

- LN

Lymph node

- LTLN

Lateral thoracic lymph node

- Rhod-PE

1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl) ammonium salt

- RT

Radiotherapy

- SCLN

Superficial cervical lymph nodes

- SPECT

Single-photon emission computed tomography

Contributor Information

Shihong Li, Department of Radiology, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900, USA.

Beth Goins, Department of Radiology, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900, USA.

William T. Phillips, Department of Radiology, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900, USA

Marcela Saenz, Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900, USA.

Pamela M. Otto, Department of Radiology, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900, USA

Ande Bao, Email: bao@uthscsa.edu, Department of Radiology, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900, USA. Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900, USA.

References

- 1.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Effects of radiotherapy and surgery in early breast cancer. An overview of the randomized trials. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1444–1455. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511303332202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forrest AP, Stewart HJ, Everington D, Prescott RJ, McArdle CS, Harnett AN, Smith DC, George WD. Randomised controlled trial of conservation therapy for breast cancer: 6-year analysis of the Scottish trial Scottish Cancer Trials Breast Group. Lancet. 1996;348:708–713. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)02133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liljegren G, Holmberg L, Bergh J, Lindgren A, Tabar L, Nordgren H, Adami HO. 10-Year results after sector resection with or without postoperative radiotherapy for stage I breast cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2326–2333. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van de Steene J, Vinh-Hung V, Cutuli B, Storme G. Adjuvant radiotherapy for breast cancer: effects of longer follow-up. Radiother Oncol. 2004;72:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veronesi U, Marubini E, Mariani L, Galimberti V, Luini A, Veronesi P, Salvadori B, Zucali R. Radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery in small breast carcinoma: long-term results of a randomized trial. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:997–1003. doi: 10.1023/a:1011136326943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polgar C, Strnad V, Major T. Brachytherapy for partial breast irradiation: the European experience. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2005;15:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vicini FA, Arthur DW. Breast brachytherapy: North American experience. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2005;15:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arthur D. Accelerated partial breast irradiation: a change in treatment paradigm for early stage breast cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2003;84:185–191. doi: 10.1002/jso.10318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dirbas FM. Accelerated partial breast irradiation: where do we stand? J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2009;7:215–225. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaidya JS, Tobias JS, Baum M, Wenz F, Kraus-Tiefenbacher U, D’souza D, Keshtgar M, Massarut S, Hilaris B, Saunders C, Joseph D. TARGeted Intraoperative radiotherapy (TAR-GIT): an innovative approach to partial-breast irradiation. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2005;15:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veronesi U, Orecchia R, Luini A, Galimberti V, Gatti G, Intra M, Veronesi P, Leonardi MC, Ciocca M, Lazzari R, Caldarella P, Simsek S, Silva LS, Sances D. Full-dose intraoperative radiotherapy with electrons during breast-conserving surgery: experience with 590 cases. Ann Surg. 2005;242:101–106. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000167927.82353.bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vicini FA, Baglan KL, Kestin LL, Mitchell C, Chen PY, Frazier RC, Edmundson G, Goldstein NS, Benitez P, Huang RR, Martinez A. Accelerated treatment of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1993–2001. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.7.1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arthur DW, Vicini FA, Kuske RR, Wazer DE, Nag S. Accelerated partial breast irradiation: an updated report from the American Brachytherapy Society. Brachytherapy. 2003;2:124–130. doi: 10.1016/S1538-4721(03)00107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baglan KL, Sharpe MB, Jaffray D, Frazier RC, Fayad J, Kestin LL, Remouchamps V, Martinez AA, Wong J, Vicini FA. Accelerated partial breast irradiation using 3D conformal radiation therapy (3D-CRT) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55:302–311. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(02)03811-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weed DW, Edmundson GK, Vicini FA, Chen PY, Martinez AA. Accelerated partial breast irradiation: a dosimetric comparison of three different techniques. Brachytherapy. 2005;4:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaidya JS, Baum M, Tobias JS, D’Souza DP, Naidu SV, Morgan S, Metaxas M, Harte KJ, Sliski AP, Thomson E. Targeted intra-operative radiotherapy (Targit): an innovative method of treatment for early breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:1075–1080. doi: 10.1023/a:1011609401132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veronesi U, Gatti G, Luini A, Intra M, Orecchia R, Borgen P, Zelefsky M, McCormick B, Sacchini V. Intraoperative radiation therapy for breast cancer: technical notes. Breast J. 2003;9:106–112. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2003.09208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ivaldi GB, Leonardi MC, Orecchia R, Zerini D, Morra A, Galimberti V, Gatti G, Luini A, Veronesi P, Ciocca M, Sangalli C, Fodor C, Veronesi U. Preliminary results of electron intraoperative therapy boost and hypofractionated external beam radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery in premenopausal women. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:485–493. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edmundson GK, Vicini FA, Chen PY, Mitchell C, Martinez AA. Dosimetric characteristics of the MammoSite RTS, a new breast brachytherapy applicator. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:1132–1139. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(01)02773-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keisch M, Vicini F, Kuske RR, Hebert M, White J, Quiet C, Arthur D, Scroggins T, Streeter O. Initial clinical experience with the MammoSite breast brachytherapy applicator in women with early-stage breast cancer treated with breast-conserving therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55:289–293. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(02)04277-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawenda BD, Taghian AG, Kachnic LA, Hamdi H, Smith BL, Gadd MA, Mauceri T, Powell SN. Dose-volume analysis of radiotherapy for T1N0 invasive breast cancer treated by local excision and partial breast irradiation by low-dose-rate interstitial implant. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56:671–680. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(03)00071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pignol JP, Keller B, Rakovitch E, Sankreacha R, Easton H, Que W. First report of a permanent breast 103Pd seed implant as adjuvant radiation treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:176–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005. 06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vicini FA, Kestin L, Chen P, Benitez P, Goldstein NS, Martinez A. Limited-field radiation therapy in the management of early-stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1205–1210. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King TA, Bolton JS, Kuske RR, Fuhrman GM, Scroggins TG, Jiang XZ. Long-term results of wide-field brachytherapy as the sole method of radiation therapy after segmental mastectomy for T(is, 1, 2) breast cancer. Am J Surg. 2000;180:299–304. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(00)00454-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wazer DE, Berle L, Graham R, Chung M, Rothschild J, Graves T, Cady B, Ulin K, Ruthazer R, DiPetrillo TA. Preliminary results of a phase I/II study of HDR brachytherapy alone for T1/T2 breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:889–897. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(02)02824-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paganelli G, De Cicco C, Ferrari ME, Carbone G, Pagani G, Leonardi MC, Cremonesi M, Ferrari A, Pacifici M, Di DA, De SR, Galimberti V, Luini A, Orecchia R, Zurrida S, Veronesi U. Intraoperative avidination for radionuclide treatment as a radiotherapy boost in breast cancer: results of a phase II study with (90)Y-labeled biotin. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:203–211. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1260-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bao A, Phillips WT, Goins B, Zheng X, Sabour S, Natarajan M, Ross WF, Zavaleta C, Otto RA. Potential use of drug carried-liposomes for cancer therapy via direct intratumoral injection. Int J Pharm. 2006;316:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harrington KJ, Rowlinson-Busza G, Syrigos KN, Uster PS, Vile RG, Stewart JS. Pegylated liposomes have potential as vehicles for intratumoral and subcutaneous drug delivery. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2528–2537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lammers T, Peschke P, Kuhnlein R, Subr V, Ulbrich K, Huber P, Hennink W, Storm G. Effect of intratumoral injection on the biodistribution and the therapeutic potential of HPMA copolymer-based drug delivery systems. Neoplasia. 2006;8:788–795. doi: 10.1593/neo.06436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu LL, Smith MJ, Sun BS, Wang GJ, Redmond HP, Wang JH. Combined IFN-gamma-endostatin gene therapy and radiotherapy attenuates primary breast tumor growth and lung metastases via enhanced CTL and NK cell activation and attenuated tumor angiogenesis in a murine model. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1403–1411. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0343-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu W, MacKay JA, Dreher MR, Chen M, McDaniel JR, Simnick AJ, Callahan DJ, Zalutsky MR, Chilkoti A. Injectable intratumoral depot of thermally responsive polypeptide-radionuclide conjugates delays tumor progression in a mouse model. J Control Release. 2010;144:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luboldt W, Pinkert J, Matzky C, Wunderlich G, Kotzerke J. Radiopharmaceutical tracking of particles injected into tumors: a model to study clearance kinetics. Curr Drug Deliv. 2009;6:255–260. doi: 10.2174/156720109788680859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zentner GM, Rathi R, Shih C, McRea JC, Seo MH, Oh H, Rhee BG, Mestecky J, Moldoveanu Z, Morgan M, Weitman S. Biodegradable block copolymers for delivery of proteins and water-insoluble drugs. J Control Release. 2001;72:203–215. doi: 10.1016/S0168-3659(01)00276-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma G, Yang J, Zhang L, Song C. Effective antitumor activity of paclitaxel-loaded poly (epsilon-caprolactone)/pluronic F68 nanoparticles after intratumoral delivery into the murine breast cancer model. Anticancer Drugs. 2010;21:261–269. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e32833410a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kikumori T, Kobayashi T, Sawaki M, Imai T. Anti-cancer effect of hyperthermia on breast cancer by magnetite nanoparticle-loaded anti-HER2 immunoliposomes. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;113:435–441. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9948-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kwak C, Hong SK, Seong SK, Ryu JM, Park MS, Lee SE. Effective local control of prostate cancer by intratumoral injection of 166Ho-chitosan complex (DW-166HC) in rats. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:1400–1405. doi: 10.1007/s00259-005-1892-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ko YT, Falcao C, Torchilin VP. Cationic liposomes loaded with proapoptotic peptide D-(KLAKLAK)(2) and Bcl-2 antisense oligodeoxynucleotide G3139 for enhanced anticancer therapy. Mol Pharm. 2009;6:971–977. doi: 10.1021/mp900006h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soundararajan A, Bao A, Phillips WT, Perez R, III, Goins BA. [186Re]Liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil): in vitro stability, pharmacokinetics, imaging and biodistribution in a head and neck squamous cell carcinoma xenograft model. Nucl Med Biol. 2009;36:515–524. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang SX, Bao A, Herrera SJ, Phillips WT, Goins B, Santoyo C, Miller FR, Otto RA. Intraoperative 186Re-liposome radionuclide therapy in a head and neck squamous cell carcinoma xenograft positive surgical margin model. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3975–3983. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Torchilin VP. Targeted pharmaceutical nanocarriers for cancer therapy and imaging. AAPS J. 2007;9:E128–E147. doi: 10.1208/aapsj0902015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elbayoumi TA, Torchilin VP. Current trends in liposome research. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;605:1–27. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phillips WT, Medina LA, Klipper R, Goins B. A novel approach for the increased delivery of pharmaceutical agents to peritoneum and associated lymph nodes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:11–16. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.037119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parker RJ, Hartman KD, Sieber SM. Lymphatic absorption and tissue disposition of liposome-entrapped [14C]adriamycin following intraperitoneal administration to rats. Cancer Res. 1981;41:1311–1317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mangat S, Patel HM. Lymph node localization of non-specific antibody-coated liposomes. Life Sci. 1985;36:1917–1925. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(85)90440-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moghimi M, Moghimi SM. Lymphatic targeting of immuno-PEG-liposomes: evaluation of antibody-coupling procedures on lymph node macrophage uptake. J Drug Target. 2008;16:586–590. doi: 10.1080/10611860802228905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oussoren C, Storm G. Liposomes to target the lymphatics by subcutaneous administration. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;50:143–156. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(01)00154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Osborne MP, Richardson VJ, Jeyasingh K, Ryman BE. Radionuclide-labelled liposomes—a new lymph node imaging agent. Int J Nucl Med Biol. 1979;6:75–83. doi: 10.1016/0047-0740(79) 90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harrington KJ, Mohammadtaghi S, Uster PS, Glass D, Peters AM, Vile RG, Stewart JS. Effective targeting of solid tumors in patients with locally advanced cancers by radiolabeled pegylated liposomes. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:243–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Phillips WT, Goins BA, Bao A. Radioactive liposomes. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2009;1:69–83. doi: 10.1002/wnan.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang SX, Bao A, Phillips WT, Goins B, Herrera SJ, Santoyo C, Miller FR, Otto RA. Intraoperative therapy with liposomal drug delivery: retention and distribution in human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma xenograft model. Int J Pharm. 2009;373:156–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.French JT, Goins B, Saenz M, Li S, Garcia-Rojas X, Phillips WT, Otto RA, Bao A. Interventional therapy of head and neck cancer with lipid nanoparticle-carried rhenium 186 radionuclide. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hamoudeh M, Kamleh MA, Diab R, Fessi H. Radionuclides delivery systems for nuclear imaging and radiotherapy of cancer. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:1329–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zweit J. Radionuclides and carrier molecules for therapy. Phys Med Biol. 1996;41:1905–1914. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/41/10/004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bao A, Goins B, Klipper R, Negrete G, Phillips WT. 186Re-liposome labeling using 186Re-SNS/S complexes: in vitro stability, imaging, and biodistribution in rats. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1992–1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bao A, Goins B, Klipper R, Negrete G, Mahindaratne M, Phillips WT. A novel liposome radiolabeling method using 99mTc-“SNS/S” complexes: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. J Pharm Sci. 2003;92:1893–1904. doi: 10.1002/jps.10441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li S, Goins B, Phillips WT, Bao A. Remote-loading labeling of liposomes with 99mTc-BMEDA and its stability evaluation: effects of lipid formulation and pH/chemical gradient. J Liposome Res. 2010 doi: 10.3109/08982101003699036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jones MN, Nicholas AR. The effect of blood serum on the size and stability of phospholipid liposomes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1065:145–152. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90224-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cullis PR, Chonn A, Semple SC. Interactions of liposomes and lipid-based carrier systems with blood proteins: Relation to clearance behaviour in vivo. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1998;32:3–17. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(97)00128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moghimi SM, Moghimi M. Enhanced lymph node retention of subcutaneously injected IgG1-PEG2000-liposomes through pentameric IgM antibody-mediated vesicular aggregation. Bio-chim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oussoren C, Zuidema J, Crommelin DJ, Storm G. Lymphatic uptake and biodistribution of liposomes after subcutaneous injection. II. Influence of liposomal size, lipid compostion and lipid dose. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1328:261–272. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2736(97)00122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chambers AF, Groom AC, MacDonald IC. Metastasis: dissemination and growth of cancer cells in metastatic sites. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:563–572. doi: 10.1038/nrc865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]