Abstract

The optically active tetracyclic ketone 8 was converted into the pentacylic core 14 of the C-19 methyl substituted Na-H sarpagine and ajmaline alkaloids via a critical haloboration reaction. The ketone 14 was then employed in the total synthesis of 19(S),20(R)-dihydroperaksine-17-al (1) and 19(S),20(R)-dihydroperaksine (2). The key regioselective hydroboration and controlled oxidation-epimerization sequence developed in this approach should provide a general method to functionalize the C(20)-C(21) double bond in the ajmaline-related indole alkaloids.

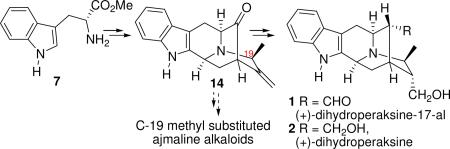

The root of Rauwolfia serpentina Benth (N.O. Apocyanaceae) has been in use in India for hundreds of years for a host of unrelated ailments.1 The plant has gained universal acclamation as a useful therapeutic weapon in the treatment of high blood pressure.2 The presence of high concentrations of alkaloids and other phytochemicals has provided a basis for the ethnomedical use of this plant in treating various medical conditions.3 The monoterpenoid sarpagine indole alkaloids 19(S),20(R)-dihydroperaksine-17-al (1) and 19(S),20(R)-dihydroperaksine (2) (Figure 1) were isolated from the hairy root culture of Rauwolfia serpentina by Stöckigt et al.4 along with 16 known alkaloids. The structures of these novel C-19 methyl substituted alkaloids were elucidated via analysis of 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopy. In addition to the asymmetric centers at C-3(S), C-5(S), C-15(R) and C-16(R) of the sarpagine framework,5a the existence of a β-methyl group at C-19 and the α-primary hydroxyl group at C-20 attracted our attention. A number of alkaloids are known which belong to the sarpagineajmaline series, and share this unique feature.5b These include the sarpagine alkaloids 10-hydroxy dihydroperaksine (3),4 O-acetyl preperakine (4),5,6 and the ajmaline-related alkaloids perakine (5)5b,7,8 and raucaffrinoline (6)5b,7,9 illustrated in Figure 1, as well as macrosalhine chloride,5 peraksine,5 verticillatine,5 10-methoxyperakine,5b,7 and vincawajine.5b,7 No enantiospecific total synthesis of this class of sarpagine-ajmaline alkaloids has appeared to date.

Figure 1.

Sarpagine-ajmaline alkaloids containing additional chiral centers at C-19(S) and C-20(R)

An objective of this research effort was to gain entry into the C-19 methyl substituted sarpagine series which would permit a study of the potential synthesis of the northern hemisphere of the bisindole alkaloid macrospegatrine10 and the basic pentacylic framework 14 would also serve as the template for the synthesis of the biogenetically important ajmaline alkaloids, perakine and raucaffrinoline.11 The fact that a biogenetic link exists between the sarpagine and ajmaline alkaloids proposed by Stöckigt et al.12 can be employed to achieve this interconversion. Herein we report the first enantiospecific total synthesis of the C-19 substituted sarpagine indole alkaloids (+)-dihydroperaksine-17-al (1) and (+)-dihydroperaksine (2).

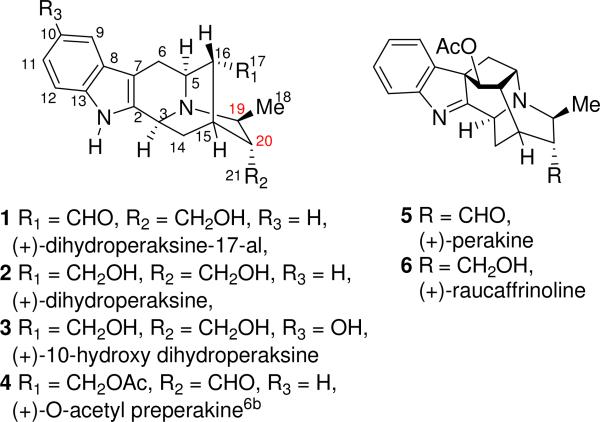

The synthesis began with the enantiospecific, stereospecific preparation of the (−)-Na-H, Nb-H tetracyclic ketone 8 from D-tryptophan methyl ester 7 on a multihundred gram scale following the procedure developed in Milwaukee.13 In order to introduce the desired stereocenter at C-19 into the sarpagan skeleton, the synthesis of the optically active R-acetylenic tosylate 11 was carried out as illustrated in Scheme 1. The racemic TIPS propargylic alcohol 9 was synthesized according to the procedure of Jones et al.14 from commercially available triisopropylsilyl acetylene in 95% yield. The optically active R-propargylic alcohol 10 [enantiomeric ratio (er) = 90:10] was synthesized from 9 via a two step oxidation/ asymmetric hydrogenation sequence under the conditions developed by Marshall et al.15 for the S-propargylic alcohol. The asymmetric hydrogenation was performed on a 25 g scale with little erosion of the er. Treatment of the optically active R-alcohol 10 with 2.2 equivalents of tosyl chloride in the presence of 4 equivalents of triethylamine at -25 °C in dichloromethane for 3.5 h, provided the R-tosylate 11. An SN2 alkylation of the Nb-nitrogen function in 8 with the tosylate 11 took place smoothly in dry acetonitrile/K2CO3 to provide the alkylated ketone which was then treated with tetrabutylammonium fluoride (TBAF·xH2O) at 0 °C in THF to provide the acetylenic ketone 12 in 96% yield (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the acetylenic ketone 12

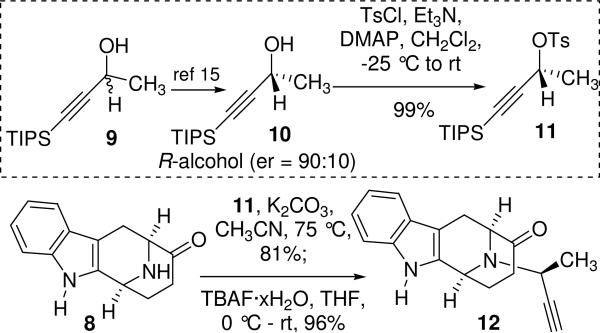

The simplest method for converting terminal alkynes to vinyl iodides in a single step is by the use of HI16 which is not useful especially for sensitive substrates. Although other methods are reported17 to achieve this important conversion, there are very few reports on the direct synthesis of α-vinyl iodides from terminal alkynes.18 In 1983 Suzuki et al.19 reported the regioselective haloboration of terminal alkynes with B-bromo-or B-iodo-9-BBN [BBN: borabicyclo(3.3.1)nonane] to furnish the respective α-vinyl halides in excellent yields and very high regioselectivities. Initial attempts at haloboration of 12, under these conditions were accompanied by inconsistent reproducibility, purification problems and very low yields. At best, up to 30% yield of the vinyl iodide 13 could be achieved by this method after varying many parameters. It was felt that the first few equivalents of the borane reagent resulted in complexation of the boron reagent to the ketone in 12 and created a steric cloud, which prevented/slowed further reaction of B-I-9-BBN from approaching the acetylenic function. With such low yields obtained in this critical step, attention turned to the use of other reagents that could be employed to achieve this conversion. The order of reactivity20 of the haloborating reagents commonly used is: B-I-9-BBN, BBr3 > BCl3 > B-Br-9-BBN >> B-Cl-9-BBN. Although BBr3 is equivalent in reactivity to B-I-9-BBN the propensity of the Nb-nitrogen in 12, to form stable borane complexes with smaller boranes as observed earlier in a similar sarpagine frameworks21 and possibly altering the course of the reaction at the terminal alkyne, rendered it unsuitable.

The haloboranes, B-I-9-BBN and dicyclohexyliodoborane [I-B(Cy)2] have been employed for the synthesis of (Z)-enolborinates exclusively from various ethyl ketones.22 I-B(Cy)2 is also a highly stereoselective reagent for the enolboration of esters23 and tertiary amides.24 If all other parameters are kept the same, the inability of B-I-9-BBN to drive the haloboration reaction to completion was felt to be due to the rigid skeleton of the bicyclo ring of B-I-9-BBN as a major factor. In contrast, the two cyclohexyl rings of I-B(Cy)2 are conformationally more flexible and should be able to adjust to the neighboring environment. As anticipated, the alkyne 12 on stirring with 2.5 equivalents of I-B(Cy)2 (added in two portions) furnished the desired boron adduct with complete consumption of the starting material 12 (Scheme 2). Subsequent protonlysis with acetic acid, generated the vinyl iodide 13. A modified workup was employed to ensure complete decomposition of excess borane, excess iodine, baseline impurities and other boron impurities which were previously observed in the aliphatic region of the NMR spectrum with B-I-9BBN. With this improved procedure 74% of pure iodo-olefin 13 was acheived. To our knowledge, this is the first example of IB(Cy)2 as the haloboration reagent for terminal alkynes. The iodo-olefin 13 was then subjected to the conditions of the recently developed palladium catalyzed α-vinylation25 to generate the key pentacyclic system 14 in 60% isolated yield (Scheme 2). The S-configuration at C-19 was confirmed by x-ray analysis of 14.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of the pentacyclic ketone 14

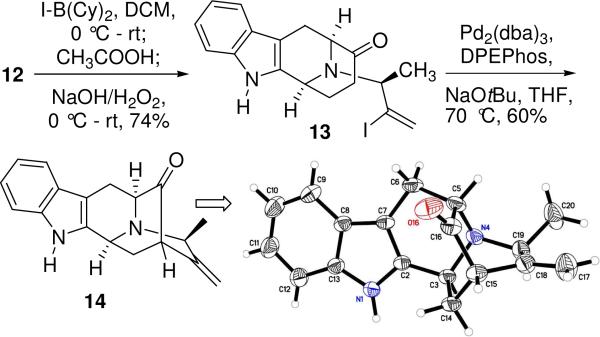

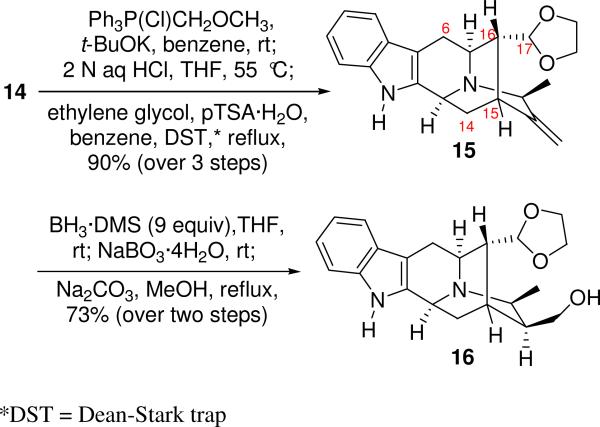

With the critical formation of the E ring in place, the pentacyclic ketone 14 was subjected to a one carbon atom homologation process at C-16 to provide the thermodynamically stable C-17 α-aldehyde even with the presence of the C-19 methyl group in the β-position,26 via a Wittig-hydrolysis-epimerization sequence (Scheme 3). The aldehydic group was then protected as the cyclic acetal 15 with ethylene glycol in the presence of p-toluene sulfonic acid monohydrate (pTSA·H2O) in refluxing benzene. With the acetal olefin 15 readily available, the hydroboration-oxidation sequence was employed to functionalize C-20. As illustrated in Scheme 3, the desired primary alcohol 16, accompanied by the tertiary alcohol was obtained in the ratio of 25:1(Both obtained as Nb-borane complexes as observed in other sarpagine systems).26 Clearly hydroboration of the C(20)-C(21) terminal olefinic bond had taken place from the α-face and supported its hindered nature from the β-face. The mixture of Nb-borane complexes of the primary alcohol 16 and tertiary alcohol was stirred in the presence of 5 equivalents of sodium carbonate in refluxing meth-anol for 5 hours, after which the desired β-primary alcohol 16 along with tertiary alcohol was obtained with the free Nb nitrogen function in 88% yield.

Scheme 3.

Regioselective hydroboration

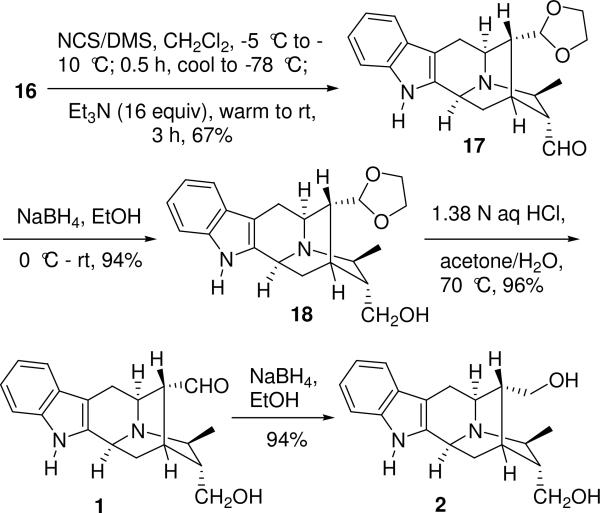

Because of the basicity of the Nb-nitrogen function in the sarpagine framework and the electron rich character of the indole nucleus (especially with the indole Na-H function), the oxidation of the primary alcohol 16 was a much bigger problem than earlier anticipated. Oxidation of 16 under various conditions27 always led to the formation of trace amounts of the aldehyde accompanied by the aldehyde Nb-oxide and some overoxidized byproduct. A modified Corey-Kim oxidation (with lesser equivalents of the reagent and lower temperature) completely eliminated the formation of any overoxidized byproducts with sole formation of the epimeric α, β-aldehydes. Complete epimerization to the α-aldehyde 17 (67% yield) was achieved in the same reaction vessel by addition of a large excess of triethylamine (up to 16 equivalents) and stirring the reaction mixture at room temperature (up to 3 h) (Scheme 4). The α-aldehyde 17 was then reduced with sodium borohydride in ethanol for 3 hours at room temperature to furnish the α-alcohol 18 in 94% yield. The acetal group in 18 was cleaved under acidic conditions (1.38 N aqueous HCl) in refluxing acetone. Advantage was taken of the basicity of the Nb-nitrogen function to remove all the non-alkaloidal impurities by washing the aqueous layer containing the HCl salt of the alkaloid with ether, followed by regeneration of the free amine by treatment with 10% aqueous ammonium hydroxide. This completed the first regiospecific, enantiospecific total synthesis of (+)-dihydroperaksine-17-al (1) in 96% yield. Reduction of 1 with sodium borohydride completed the first total synthesis of (+)-dihydroperaksine (2) as well (Scheme 4). The synthetic alkaloids (1) and (2) were identical on TLC (including a mixed TLC sample) to the sample of natural (+)-dihydroperaksine-17-al (1) and natural (+)-dihydroperaksine (2) kindly supplied by Professor Joachim Stöckigt at Johannes Gutenberg-University (Germany).28 The spectral data of 1 (1H and 13C NMR) are in complete agreement with that of the natural product. For compound 2, some ambiguity was observed in the 1H NMR (difference in chemical shifts) and a comparison of its 13C NMR with the natural product indicated that C-15 and C-6 carbon atoms were interchanged. A detailed NMR anlaysis of the synthetic alkaloid 2 including 13C DEPT 135 as well as 2D COSY, HSQC, NOESY and 1D NOE experiments (see Supporting Information) unequivocally support the structure as indicated in Scheme 4, in agreement with that of natural (+)-dihydroperaksine (2).

Scheme 4.

Completion of the total synthesis of dihydroperaksine-17-al (1) and dihydroperaksine (2)

In summary, the first enantiospecific, stereospecific total synthesis of 19(S),20(R)-dihydroperaksine-17-al (1) and 19(S),20(R)-dihydroperaksine (2) has been accomplished in overall yields of 10.2% (14 reaction vessels) and 9.6% (15 reaction vessels), respectively from commercially available D-(+)-tryptophan methyl ester 7. The critical haloboration of terminal alkyne 12 was achieved by employing dicylcohexyliodoborane as the haloborating agent for the first time. The stereospecific synthesis of the core pentacyclic ketone 14 contained in the C-19 methyl-substituted sarpagine alkaloids thus provides a potentially general entry into a whole series of biosynthetically important monterpene C-19 substituted indole alkaloids.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Professor J. Stöckigt (Johannes Gutenberg-University)28 for providing samples of 1 and 2 for TLC comparison. We wish to acknowledge NIMH (in part) and the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation for support of this work. X-ray crystallographic studies were supported by NIDANRL Interagency Agreement Number Y1-DA1101.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and spectral data for all new compounds including x-ray data for 14 and 1H and 13C comparison tables between natural and synthetic 1 and 2. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Ebadi M. Pharmacodynamic Basis of Herbal Medicine. 2nd ed. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2006. pp. 515–519. Chapter 56. [Google Scholar]

- 2.a Vakil RJ. Brit. Heart J. 1949;11:350. doi: 10.1136/hrt.11.4.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Vakil RJ. Circulation. 1955;12:220. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.12.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harisaranraj R, Suresh K, Saravanababu S. Advan. Biol. Res. 2009;3:174. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheludko Y, Gerasimenko I, Kolshorn H, Stöckigt J. J. Nat. Prod. 2002;65:1006. doi: 10.1021/np0200919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a Lounasmaa M, Hanhinen P, Westersund M. In: The Alkaloids. Cordell GA, editor. Vol. 52. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1999. pp. 103–195. references cited therein. [Google Scholar]; b Lounasmaa M, Hanhinen P. J. Nat. Prod. 2000;63:1456. doi: 10.1021/np000206d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akinloye BA, Court WE. Planta Med. 1979;37:361. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-971677. bStereochemistry at C-20 depicted as per ref 5b.

- 7.Lounasmaa M, Hanhinen P. In: The Alkaloids. Cordell GA, editor. Vol. 55. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2001. pp. 1–89. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ulshafer PR, Bartlett MF, Dorfman L, Gillen MA, Schlittler E, Wenkert E. Tetrahedron Lett. 1961:363. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Libot F, Kunesch N, Poisson J. Phytochemistry. 1980;19:989. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin X, Zheng Q, Zhang Y. J. Struct. Chem. 1987;6:89. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takayama H, Phisalaphong C, Kitajima M, Aimi N, Sakai S, Stöckigt J. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1991;39:266. [Google Scholar]

- 12.a Pfitzner A, Stöckigt J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:5197. [Google Scholar]; b Ruppert M, Ma X, Stöckigt J. Curr. Org. Chem. 2005;9:1431. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu P, Wang T, Li J, Cook JM. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:3173. doi: 10.1021/jo000126e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones GB, Wright JM, Plourde GW, II, Hynd G, Huber RS, Mathews JE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:1937. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marshall JA, Eidam P, Eidam HS. Org. Synth. 2007;84:120. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith MB, March J. March's Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure. 6th ed. Wiley-Interscience; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2007. pp. 999–1250. Chapter 15. [Google Scholar]

- 17.a Katagiri T, Fujiwara K, Kawai H, Suzuki T. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:3242. [Google Scholar]; b Va P, Roush WR. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:5768. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2007.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Nielsen TE, Le Quement S, Tanner D. Synthesis. 2004:1381. [Google Scholar]; d Kazmaier U, Pohlman M, Schauss D. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2000:2761. [Google Scholar]; e Kikukawa K, Umekawa H, Wada F, Matsuda T. Chem. Lett. 1988:881. [Google Scholar]

- 18.a Gao F, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10961. doi: 10.1021/ja104896b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kawaguchi S, Ogawa A. Org. Lett. 2010;12:1893. doi: 10.1021/ol1005246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Campos PJ, García B, Rodríguez MA. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:6111. [Google Scholar]; d Reddy CK, Periasamy M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:1919. [Google Scholar]; e Kamiya N, Chikami Y, Ishii Y. Synlett. 1990:675. [Google Scholar]; f Gras J-L, Kong Win Chang YY, Bertrand M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;23:3571. [Google Scholar]

- 19.a Hara S, Dojo H, Takinami S, Suzuki A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:731. [Google Scholar]; b Suzuki A. Rev. Heteroatom. Chem. 1997;17:271. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki A, Brown HC. Organic Synthesis Via Boranes. Vol. 3. Aldrich Chemical Company, Inc.; Milwaukee, WI: 2003. pp. 5–36. Chapter 2. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu X, Cook JM. Org. Lett. 2002;3:4023. doi: 10.1021/ol0101990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown HC, Ganesan K, Dhar RK. J. Org. Chem. 1993;58:147. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ganesan K, Brown HC. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:2336. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ganesan K, Brown HC. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:7346. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liao X, Zhou H, Yu J, Cook JM. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:8884. doi: 10.1021/jo061652u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edwankar CR, Edwankar RV, Rallapalli SK, Cook JM. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2008;3:1389. [Google Scholar]

- 27.a Mancuso AJ, Huang S-L, Swern D. J. Org. Chem. 1978;43:2480. [Google Scholar]; b Dess DB, Martin JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:7277. [Google Scholar]; c Corey EJ, Kim CU. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972;94:7586. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Currently Dr. J. Stöckigt is Professor at the College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Zhejiang University (Hangzhou, China) and retired from the Institute of Pharmacy, Johannes Gutenberg-University, Mainz, Germany.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.