Abstract

Aims

Evaluate the effects of lowering the blood alcohol concentration (BAC) limit on road traffic fatalities and injuries in the State and capital of Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Design

Time series analysis using ARIMA modelling.

Setting

The augmented risk of road traffic accidents when under the influence of alcohol is well documented. However, many developing countries do not have a drink-driving law or have BAC limits that are above 0.05 g/dl. In Brazil, a new law introduced in 2008 has lowered the BAC limit for drivers from 0.06 to 0.02, but the effectiveness in reducing traffic accidents remains uncertain.

Measurements and participants

Data on injuries and deaths caused by road traffic accidents in both regions were collected from January 2001 to June 2010, comprising a total of 1,417,087 injuries and 51,561 fatalities.

Findings

The new traffic law was responsible for significant reductions in traffic injuries and fatalities rates in both localities (P<0.05). A stronger effect was observed for traffic fatalities (−7.2 and −16.0% in the average monthly rate in the State and capital, respectively) compared to traffic injuries rates (−1.8 and −2.3% in the State and capital, respectively).

Conclusions

Lowering BAC limits had a greater impact on traffic fatalities than injuries, with a higher effect in the capital where presumably the police enforcement was enhanced, and points to the relevance of these measures on the effectiveness of such law. Rigorous investigations on the effects of strategies derived from high-income countries to control alcohol-impaired driving should be promoted in developing countries.

Keywords: Alcohol, Drink-driving, Injuries, Law, Road traffic

Introduction

In 2004, road traffic accidents ranked 9th in the world’s leading causes of death and burden of disease, being responsible for 1.3 million deaths and 41.2 million years lost due to premature mortality and disabilities globally. If this scenario already expresses that road traffic accidents are a major public health issue worldwide, the future projections are of greater concern, since road traffic fatalities are estimated to increase to 2.4 million in 2030, primarily due to the economic growth attributed to low-and middle-income regions [1].

Moreover, in these countries the costs of transport accidents in terms of medical treatment and lost productivity correspond to a significant portion of the public budget. For example, the annual expenditure for traffic accidents on Brazilian roads is estimated in the R$22 billions, which is equivalent to 1.2% of Brazil’s nominal gross domestic product (GDP) [2].

The association between alcohol consumption and road traffic accidents is well documented by the literature, as are the main psychopharmacological effects of alcohol on human behaviour which are considered important risk factors for violence and accident events [3]. There is substantial evidence that alcohol impairs motor coordination and decision making in drivers, thus enhancing risk-taking behaviour and the likelihood of accidents [4].

The measurement of blood alcohol concentration (BAC) is considered a feasible method for inferring the influence of alcohol on drivers’ performance, including the indirect analysis by breathalyzers, which is an effective way to provide accurate BAC estimates during field impairment testing [5]. A large study comparing crash and non-crash drivers found that the relative risk of a crash begins to increase at 0.04–0.05 g/dl BAC, and increases steadily at BACs higher than 0.10 [6], which is in accordance with international recommendations regarding traffic safety suggesting that countries should adopt BAC limits of 0.05 or below [7].

However, many countries do not have a drink-driving law yet or have blood alcohol concentration (BAC) limits that are above 0.05 [7]. This is especially relevant for low- to middle-income countries, where there is scarce evidence on drink-driving attitudes and strategies aiming to control drunk drivers. In fact, the vast majority of publications on alcohol’s association with traffic accidents derive from high-income countries, which more often than not, also have smaller road traffic death rates as well as report a number of strategies which demonstrate positive effects of reducing driving under the influence (DUI) of alcohol [8].

Brazil is the Southern Hemisphere’s biggest country with almost 200 million inhabitants, and despite its remarkable economic development during the last decade, traffic accidents are still one of the main causes of death, with around 35,000 people dying every year [7]. Additionally, according to a national telephone survey of the general population, binge drinking has increased steadily from 16.2% in 2006 to 18.9% in 2009 [9].

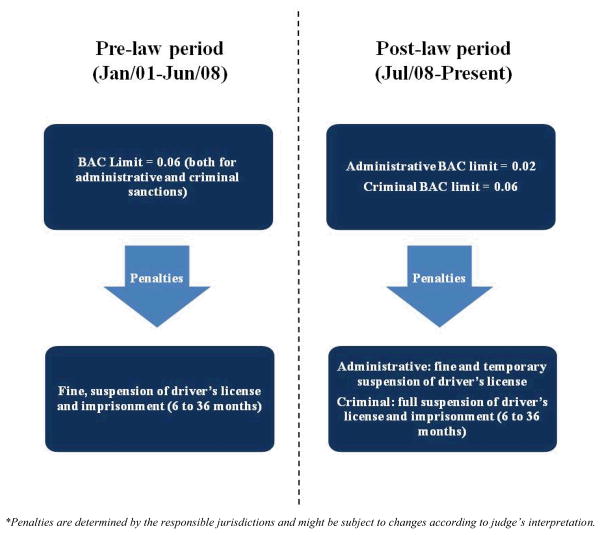

Previous research on fatal traffic accident victims in the city of Sao Paulo (the major urban center of Brazil) found that 39.4% of those presented BACs higher than 0.01, with 42.3% of drivers presenting BACs over 0.06 [10]. Aiming to tackle this serious public health issue, a new national law introduced in June 2008 has reduced the BAC limit for drivers from 0.06 to 0.02 [11]. This new enactment also made a distinction between administrative (fine and temporary driver’s license suspension) and criminal sanctions (full suspension of driver’s license and detention) based on BAC results, which strengthened the punishment for those driving above the legal limits (see Figure 1 for more details).

Figure 1.

Changes in Brazilian law concerning blood alcohol concentration (BAC) limit for drivers after the new traffic law implemented in June 2008.

The effectiveness of such a strategy has already been demonstrated by Fell & Voas (2006) in a large review of independent studies in fourteen states in the United States. The meta-analysis conducted by these authors indicated that lowering the BAC limit from 0.10 to 0.08 resulted in a 14.8% reduction in alcohol-related traffic fatalities, and that lowering the BAC limit to 0.05 would possibly produce an additional reduction of 6–18% [12]. Similarly, a traffic legislation change carried out by the Japanese government in 2002, which lowered the permissible BAC from 0.05 to 0.03 showed significant reductions in all alcohol-related and non-alcohol-related traffic injuries during the post-law period [13].

While these interventions might be transferable to developing countries where scientific data on this issue is scant [14], the effectiveness of the new traffic law in reducing traffic accidents in Brazil remains uncertain, and should certainly be addressed taking into account typical differences between developed and developing countries. For instance, health and social disparities among countries may influence policy intervention results, and local research evidence may play a major role in the promotion of low-cost and effective strategies in developing countries [15].

The aim of this investigation was to analyze the effects of lowering the BAC limit for road traffic fatalities and injuries in both the State and capital of Sao Paulo in Brazil, and test the hypothesis that effects caused by the new traffic law vary according to outcomes (injuries versus fatalities) and two distinct regions might serve as a proxy for differences in law enforcement regarding DUI (State versus capital).

The hypothesis that differences in traffic law enforcement vary between the two distinct regions studied is based primarily on the greater rates of police activities (e.g. rate of stolen vehicles retrieved per inhabitants) observed in the capital compared with the State [16], which supports the assumption that DUI investigations follow the same discrepant pattern in those regions.

To our knowledge, this represents the first study on the effectiveness of lowering legal BAC limits with the goal of diminishing road traffic accidents in developing countries, and may inform similar countries where the scientific data on this issue has not advanced.

Methods

Study design, data source and procedures

The Public Security Office of Sao Paulo is responsible for the collection of data and statistics on traffic accidents in the State of Sao Paulo, which has 645 municipalities distributed across 248,600 km2 with almost 42 million inhabitants, including the city of Sao Paulo which accounts for 26.7% of the entire State’s population.

Traffic accident injured victims are readily attended by emergency units and police officers at the event scene, while fatal victims are submitted to necropsy at the nearest medico-legal examination center. Accordingly, information on traffic accident victims is gathered by police officers based on the victim’s outcome, which in turn is compiled in a database coordinated by the Public Security Office.

It is important to note that while most fatal cases are registered, injured victims, especially those with less severe trauma, have a greater likelihood of not being attended by police officers because victims may rapidly evade the accident site, or due to absence of the police workforce at the time of accident (e.g. police strike period).

Data extracted from police reports on deaths and injuries caused by road traffic accidents were collected from January 2001 to June 2010, comprising 1,417,087 non-fatal and 51,561 fatal traffic accident cases during the entire study period (9 years and 6 months). The number of cases per month used in the present analysis was based on the accident’s profile collected by police officers at the event scene and represents the number of accident events but not the total number of traffic accident victims in the given period.

In the case where an accident included both injuries and fatalities, only the most severe was included in the database. Additionally, the number of fatalities is most likely an underestimation of the actual number of fatal victims, since it has been estimated by previous studies that 61.6% of deaths occur on the same day of the traffic accident [17], with the remaining usually not being covered by the police reports used in the present study.

The data collected for the State of Sao Paulo did not include cases from the city of Sao Paulo, which means that the cases for each region are mutually exclusive. Monthly rates of traffic injuries and fatalities per 100,000 inhabitants derived from population data during the study period [18] were used as the main outcome variables.

Time series analysis was conducted using a fitted ARIMA (autoregressive integrated moving average) model with adjustment for seasonality and the effects of the new traffic law were evaluated by an intervention analysis for each outcome and region.

The research was based on confidential data maintained by the Public Security Office of Sao Paulo and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Sao Paulo Medical School.

Statistical Methods

To evaluate the effect of the new legislation on traffic injuries and fatalities, interrupted time series analysis was performed using the technique of ARIMA models. Time series data has special features such as non-stationary and auto-correlations, which may derive biased and inefficient estimates when modeled inappropriately [19]. ARIMA modelling requires data to be stationary, assessed using Dickey-Fuller test. If the raw data is not stationary, it is de-trended through differencing process.

Furthermore, ARIMA model allows specification of temporal structure for error terms, through autoregressive (AR) or moving-average (MA) process. Since monthly data was used in current analysis, seasonal pattern was also incorporated in ARIMA models which are specified by the expression (p,d,q) (P,D,Q). The first term (p,d,q) refers to regular model specification; e.g. 1st-order difference (d) and AR (p) or MA (q) error structure. The second term (P,D,Q) is the seasonal component; e.g. the seasonal difference (D) and corresponding seasonal error structure (P or Q). The residuals of the estimated model should be white noise, which was tested using the Box-Ljung Q-test and also evaluated by examining the autocorrelation (AC) and partial autocorrelation (PAC) of estimated residuals.

Rates of traffic injuries and fatalities per 100,000 inhabitants were analyzed as outcome series in the model, with a total of 114 monthly observations for each outcome series in both State and capital of Sao Paulo. In the interrupted time series analysis, intervention was represented as a dummy variable. To estimate the effect of the new traffic law implementation, a dummy variable was created with 90 months before intervention coded as 0 and 24 months after intervention coded as 1.

An additional dummy variable was included in the intervention analysis to establish the effect of a strike period in the police force between September and November 2008, which likely reduced the collection of data on traffic casualties and could not be interpreted as a direct effect of the new traffic law. The models were fitted using Eviews version 5 [20] and interpreted in view of their significant levels (P<0.05).

Results

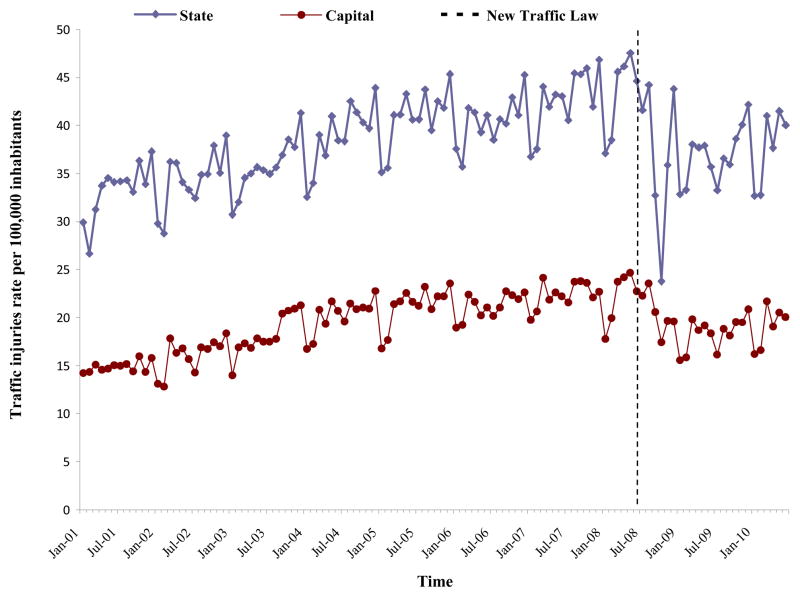

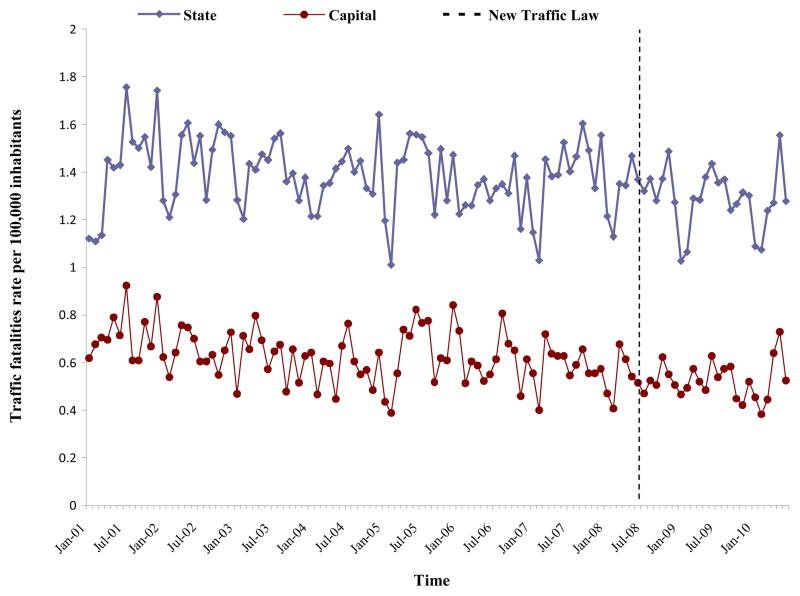

Traffic injuries have been increasing since 2001, both in the State and capital of Sao Paulo, and it began declining even before the law, showing a greater reduction in the post-law period (Figure 2). Traffic fatalities in the State, however, remained constant from 2001 until 2008, whereas in the capital traffic fatalities have been decreasing since 2001 (Figure 3), with both regions showing a trend for reduction on this outcome after the law.

Figure 2.

Trends in traffic injuries rates (per 100,000 inhabitants) in the State and capital of Sao Paulo covering the period from January 2001 to June 2010.

Figure 3.

Trends in traffic fatalities rates (per 100,000 inhabitants) in the State and capital of Sao Paulo covering the period from January 2001 to June 2010.

Table 1 presents the results for the time series and intervention analysis, which demonstrate the effects of the new traffic law implementation on traffic casualties in terms of estimated rates per month, as well as the possible interventional effect caused by the police strike period on the outcomes.

Table 1.

Estimated effects of the new traffic law implemented in June 2008 on traffic fatalities and injuries rates (per 100,000 inhabitants) in the State and capital of Sao Paulo derived from Interrupted ARIMA modelling of data from January 2001 to June 2010.

| Estimate | SE | P-value | Q(12) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traffic injuries | |||||

| State of Sao Paulo (0,1,1) (1,0,0) | 16.58 | 0.084 | |||

| New traffic law | −0.705 | 0.304 | 0.023* | ||

| Police strike | −11.42 | 1.289 | <0.001* | ||

| Capital of Sao Paulo (0,1,1) (1,0,0) | 15.05 | 0.130 | |||

| New traffic law | −0.441 | 0.217 | 0.044* | ||

| Police strike | −2.072 | 0.745 | 0.007* | ||

| Traffic fatalities | |||||

| State of Sao Paulo (1,0,0) (1,0,0) | 10.68 | 0.383 | |||

| New traffic law | −0.100 | 0.042 | 0.020* | ||

| Police strike | 0.072 | 0.071 | 0.315 | ||

| Capital of Sao Paulo (1,0,0) (0,0,0) | 11.42 | 0.409 | |||

| New traffic law | −0.104 | 0.032 | 0.002* | ||

| Police strike | 0.032 | 0.072 | 0.660 |

Intervencional effect was considered statiscally significant (P<0.05)

Four ARIMA models are presented for rates of traffic injuries and fatalities in the State and capital of Sao Paulo, separately. In addition to the intervention effect estimates, each model presents the specification of ARIMA modelling. For example, the expression (0,1,1) (1,0,0) for injuries in the State of Sao Paulo indicates the model which was fitted on the first-order difference of the injury series and the error structure which was specified by a first-order moving average, as well as a seasonal (12-month lag) autoregressive term. Also shown in Table 1 for each model are the results from Box-Ljung Q-test on residual correlation. Test statistics for all lags were performed and the Box-Ljung statistics at lag 12 is presented for the seasonality pattern of series.

Across all four models, the new traffic law significantly reduced traffic injuries and fatalities rates (P<0.05). Traffic injuries rates reduced 0.71 and 0.44 per 100,000 inhabitants a month in the State and capital of Sao Paulo, respectively, while fatalities rates decreased 0.10 per 100,000 inhabitants a month in both regions.

To put it another way, a somewhat stronger effect was observed for traffic fatalities (a decrease of −7.2 and −16.0% in the average monthly rate in the State and capital of Sao Paulo, respectively) compared to traffic injuries rates (−1.8 and −2.3% in the State and capital, respectively) in the post-law period, with the effect being higher in the capital for all the outcomes than in the State.

The police strike was significantly associated with lower records of injuries, but not with fatalities rates, for the State and capital. As shown from Box-Ljung Q-test, the model fit was good in terms of residual auto-correlation for the two models on fatalities rates, whereas fitting for the other two models on injuries rates was somewhat less satisfactory but still acceptable.

Discussion

The results presented here indicate that the traffic law which reduced the BAC limit for driving in Brazil since June 2008 had a significant impact on traffic injuries and fatalities in both the State and capital of Sao Paulo, being responsible for a greater decline in fatalities than injuries rates. Moreover, the reduction effects of the legislation intervention were found to be greater in the capital than in the State.

Time series analysis has proven to be a better method of interpreting the change in trend associated with an intervention [13,21]. Therefore the findings presented here based on this methodology may provide a better understanding on the effectiveness of lowering BAC limits for drivers, since research on interventions for controlling alcohol-related accidents presents many methodological weaknesses [22], particularly for low-and middle-income countries where data on this issue is scarce and in great demand [23].

In a study on the effectiveness of BAC limit reduction in 22 US states, Kaplan & Prato [24] demonstrated that lowering the BAC limit to 0.08 was more effective in reducing the number of alcohol-related traffic fatalities than traffic accidents, which is in accordance with our findings and suggests that BAC reduction laws may have a greater influence on those drivers that are more likely to be involved in severe traffic accidents.

Although establishing a correlation between BAC level and severity of outcomes in traffic accident victims stills remains inconclusive [25], there is evidence that lowered legal limits show the strongest effects at highest BAC levels [26]. In view of these findings, it may be hypothesized that the new enactment was more effective in reducing more severe traffic accidents which might be those most related with heavy drinking habits, as a consequence of a differential deterrence effect of the legislation [27]. However, future research regarding BAC law compliance across different drinking groups and society levels is needed to address this important issue, since the interventional effect may vary considerable depending on the country/population characteristics, as the results presented here suggest.

Differences regarding the effect of the new traffic law between the two regions studied may be explained by divergent police enforcement and other supporting measures, such as media coverage and preventive actions in each locality. As noted above, the assumption that traffic police enforcement, including DUI measures, is greater in the capital than in the State of Sao Paulo sustain this argument, since the effects of the new enactment were more pronounced in the capital than the State.

The law was preceded by wide coverage by the media in the entire country during the initial months after the enactment, which may have promoted compliance and enforcement. Additionally, private initiatives, by cab drivers and bar owners also aimed to reduce drunk driving. There is some evidence showing that media advocacy can increase public and political attention to alcohol problems, but public information campaigns and designated driver schemes are generally ineffective in reducing harmful alcohol use [28].

Furthermore, the decrease in traffic injuries in both regions was observed even during the period before the law, when preventive actions and police enforcement were already being used for controlling alcohol-impaired driving, which points to the importance of enactment of such a law as a reinforcement strategy.

Nevertheless, it remains to be seen if the observed effects are temporary and restricted to immediate post-law period, and how differences in supporting measures may help explain the disparity observed between the two regions studied, in order to achieve a more general deterrent effect by improving sanctions for drunk drivers and local awareness of this issue.

At the same time, public authorities must be cautious about major changes in drink-driving laws such as lowering BAC limits and increasing penalties because these measures may increase the likelihood of refusing a BAC test to avoid criminal conviction [29], which has been demonstrated to be a great challenge ahead for the current situation regarding DUI investigations in Brazil [30], as well as other developing countries.

A recent cohort study conducted in France revealed that negative drinking-driving attitudes have increased during the last decade, despite the remarkable decreases in alcohol consumption and road fatalities observed during the same period due to substantial enhancement of traffic law enforcement in that country [31]. The authors correctly concluded that perceived punishment is less effective among DUI offenders, since the chance of being placed under arrest is much lower than with other traffic law offenses such as speed limit violations. In light of this, the right combination of different strategies aiming to control the use of alcohol by drivers, including public support and the involvement of several levels of government for improving police enforcement effectiveness [26], may hold the key to successfully reducing alcohol-related traffic accidents.

When analyzing an intervention strategy in series observations over time, it is also very important to account for the impact of other policies or events that might influence observed trends, and lead to erroneous estimates of the effectiveness of the intervention variable under study.

The police strike that affected the collection of data during a three-month period was responsible for significant changes in traffic injuries observed in the State and capital of Sao Paulo, but it did not influence traffic fatalities reports in these regions. This was mainly due to the greater likelihood of non-fatal traffic victims not being registered during the police strike period compared to fatal traffic victims. Hence, this finding is important for supporting the notion that traffic casualties are subject to numerous overlooked interventions and/or policies, which should be included in future research that is fundamental for guiding new traffic legislation.

This study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the data obtained did not provide victims’ BAC in the traffic casualties studied; therefore we were not able to analyze the effect of the new law on BAC-positive victims compared to those who did not drink.

In addition, the method of data collection used in police reports may present bias that could have influenced the differential findings for fatalities compared to injuries. Other indicators including alcohol-related traffic accidents should be incorporated in the present database, further improving the integration of routine police reports with toxicological data and the quality of future investigations.

Secondly, it was not possible to account for other concomitant policies or trends in alcohol consumption and motor vehicle utilization that might affect the occurrence of traffic casualties during the study period. For example, a developing country such as Brazil is undergoing an increase in both alcohol use and motor vehicle utilization as a consequence of the economic growth in recent years, which likely contributes to an underestimation of the law’s effect on traffic accidents.

However, the use of time series analysis (ARIMA modelling) has helped to overcome many difficulties in interpreting the effects of a specific intervention using time series data, and also make possible inferences about a major police strike which could have lead to serious misinterpretations.

Finally, this research only focused on observations collected for a particular Brazilian region which may present important differences in traffic accident rates, police enforcement and contextual factors from other regions in the country or internationally. Even so, our study represents the first and a necessary attempt to develop permanent efforts in evaluating traffic measures concerning alcohol impaired driving in a large developing region that might help reverse the high morbidity and mortality from traffic accidents, as has been done in high-income countries in the last 30 years [32].

Perhaps the best strategy against alcohol-related traffic accidents is improvement of the currently established strategies, rather than a search for new and revolutionary measures. Our results suggest that lowering BAC limits was a successful strategy in Brazil and can be one of those tools, but special attention must be given to possible differential deterrence effects relied on police enforcement level and other extralegal factors that should be addressed by other regions sharing the same problem.

Future research conducted in developing regions associated with the knowledge acquired in developed countries may introduce new inputs for the amelioration of this global health issue and be decisive for the accomplishment of further strategies aiming to control the large number of casualties and financial costs associated with alcohol consumption by drivers.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank especially the Public Security Office of Sao Paulo for giving us all the necessary support for this research. We also thank CAPES Foundation for the financial support granted to Andreuccetti G (Proc. n° 4311/10–8).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Kahn T works for the Public Security Office of Sao Paulo, which is responsible for the collection of data on traffic accidents in the State of Sao Paulo. Ponce JC is a forensic criminal expert involved in the investigation of crimes in the city of Sao Paulo. All the others authors are involved solely in academic research and declare no other conflict of interest. The corresponding author received a grant from CAPES Foundation, Ministry of Education of Brazil, for developing his doctoral studies at the University of Sao Paulo Medical School. The sponsor has not participated in the study design or in any decision concerning the writing and submission of the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.WHO. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.IPEA/DENATRAN/ANTP. Impactos sociais e econômicos dos acidentes de trânsito nas rodovias brasileiras [Social and economic impact of traffic accidents on Brazilian roads] Brasilia: Institute for Applied Economic Research; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Room R, Babor T, Rehm J. Alcohol and public health. Lancet. 2005;365(9458):519–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17870-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly E, Darke S, Ross J. A review of drug use and driving: epidemiology, impairment, risk factors and risk perceptions. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2004;23(3):319–44. doi: 10.1080/09595230412331289482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones AW. Medicolegal Alcohol Determinations — Blood- or Breath-Alcohol Concentration? Forensic Sci Rev. 2000;12:23–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blomberg RD, Peck RC, Moskowitz H, Burns M, Fiorentino D. The Long Beach/Fort Lauderdale relative risk study. J Safety Res. 2009;40(4):285–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO. Global status report on road safety: time for action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ameratunga S, Hijar M, Norton R. Road-traffic injuries: confronting disparities to address a global-health problem. Lancet. 2006;367(9521):1533–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68654-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.VIGITEL. Vigilância de Fatores de Risco e Proteção para Doenças Crônicas por Inquérito Telefônico System [Surveillance System of Risk and Protective Factors for Chronic Diseases by Telephone Interview] Brasilia, DF: Brazilian Ministry of Health; 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ponce JC, Munoz DR, Andreuccetti G, Carvalho DG, Leyton V. Alcohol-related traffic accidents with fatal outcomes in the city of Sao Paulo. Accid Anal Prev. 2011;43(3):782–7. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2010.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lei 11.705, de 19 de Junho de 2008 [Law 11705, edited on June 19, 2008] Brazil: Diário Oficial da União; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fell JC, Voas RB. The effectiveness of reducing illegal blood alcohol concentration (BAC) limits for driving: evidence for lowering the limit to .05 BAC. J Safety Res. 2006;37(3):233–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagata T, Setoguchi S, Hemenway D, Perry MJ. Effectiveness of a law to reduce alcohol-impaired driving in Japan. Inj Prev. 2008;14(1):19–23. doi: 10.1136/ip.2007.015719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forjuoh SN. Traffic-related injury prevention interventions for low-income countries. Inj Control Saf Promot. 2003;10(1–2):109–18. doi: 10.1076/icsp.10.1.109.14115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nantulya VM, Reich MR. Equity dimensions of road traffic injuries in low- and middle-income countries. Inj Control Saf Promot. 2003;10(1–2):13–20. doi: 10.1076/icsp.10.1.13.14116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.SSP/SP. Estatísticas criminais [Criminal statistics] Public Security Office; Sao Paulo: 2010. Available at: http://www.ssp.sp.gov.br/estatistica/default.aspx (accessed 28 March 2011). (Archived by WebCiteR at http://www.webcitation.org/5xWxl8BoG) [Google Scholar]

- 17.CET. Relatório anual de acidentes de trânsito fatais no município de São Paulo [Annual report on fatal traffic accidents in the city of Sao Paulo] Sao Paulo: Company of Traffic Engineering; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.SEADE. Informações dos municípios paulistas [Information on municipalities from the State of Sao Paulo] State System of Data Analysis Foundation; 2001–2010. Available at: http://www.seade.gov.br/produtos/imp/index.php?page=welcome (accessed 10 February 2011). (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/query?id=1302121174847530) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greene WH. Econometric analysis. 4. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.EViews. EViews 5 user’s guide. Irvine, CA: Quantitative Micro Software; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramstedt M. Alcohol and fatal accidents in the United States--a time series analysis for 1950–2002. Accid Anal Prev. 2008;40(4):1273–81. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goss CW, Van Bramer LD, Gliner JA, Porter TR, Roberts IG, Diguiseppi C. Increased police patrols for preventing alcohol-impaired driving. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD005242. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005242.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perel P, Ker K, Ivers R, Blackhall K. Road safety in low- and middle-income countries: a neglected research area. Inj Prev. 2007;13(4):227. doi: 10.1136/ip.2007.016527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan S, Prato CG. Impact of BAC limit reduction on different population segments: a Poisson fixed effect analysis. Accid Anal Prev. 2007;39(6):1146–54. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plurad D, Demetriades D, Gruzinski G, Preston C, Chan L, Gaspard D, et al. Motor vehicle crashes: the association of alcohol consumption with the type and severity of injuries and outcomes. J Emerg Med. 38(1):12–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mann RE, Macdonald S, Stoduto LG, Bondy S, Jonah B, Shaikh A. The effects of introducing or lowering legal per se blood alcohol limits for driving: an international review. Accid Anal Prev. 2001;33(5):569–83. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(00)00077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mann RE, Smart RG, Stoduto G, Adlaf EM, Vingilis E, Beirness D, et al. The effects of drinking-driving laws: a test of the differential deterrence hypothesis. Addiction. 98(11):1531–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson P, Chisholm D, Fuhr DC. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of policies and programmes to reduce the harm caused by alcohol. Lancet. 2009;373(9682):2234–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60744-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Voas RB, Kelley-Baker T, Romano E, Vishnuvajjala R. Implied-consent laws: a review of the literature and examination of current problems and related statutes. J Safety Res. 2009;40(2):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andreuccetti G, Carvalho HB, Cherpitel CJ, Kahn T, Ponce J, de C, Leyton V. The right choice on the right moment. Addiction. 105(8):1498–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Constant A, Lafont S, Chiron M, Zins M, Lagarde E, Messiah A. Failure to reduce drinking and driving in France: a 6-year prospective study in the GAZEL cohort. Addiction. 105(1):57–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02725.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Accelerating action on road safety. Lancet. 2008;371(9617):960. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60426-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]