Abstract

The ability to apply precise inputs to signaling species in live cells would be transformative for interrogating and understanding complex cell signaling systems. Here, we report a method for applying custom signaling inputs using feedback control of an optogenetic protein-protein interaction. We apply this strategy for perturbation of protein localization and phosphoinositide 3-kinase activity, generating time-varying signals and clamping signals to buffer against cell-to-cell variability or pathway activation changes.

Keywords: Optogenetics, feedback control, systems biology, single cell methods

To dissect how cell signaling networks sense, encode and process information, we need not only a parts list but also an understanding of how their constituent molecular components vary over time in response to diverse input signals. One powerful set of approaches for interrogating cellular circuits combines controlled, time-varying perturbations with live cell signaling activity readouts1-3. This strategy can be used to analyze how a pathway maps diverse inputs to outputs and to distinguish the nature, timescale, and strength of feedback connections acting within a biological network.

Genetically encoded light-gated proteins (optogenetics) represent a promising technology for delivering precise intracellular inputs to individual cells. However, their broad application faces three challenges. First, cells vary in their expression level of optogenetic components, so the same light input will drive different activity levels across a population of cells. Second, even within an individual cell the relationship between light and activity can be complex and nonlinear. Thus, it is very difficult to identify how light levels should be varied to drive a defined timecourse of intracellular activation. Finally, many signaling pathways incorporate regulatory connections whose strength varies over time. Even delivering a constant level of pathway activity can require light inputs that compensate for the timing and strength of intracellular feedback.

In this study, we address each of these challenges by coupling a tunable optogenetic module with automated control of its light input (Fig. 1a). Using live-cell measurements of intracellular activation to update light levels in real time, we implemented a computational feedback controller to act as a ‘concentration clamp,’ analogous to voltage clamping for neuron excitation4 or positional clamping5 for molecular mechanical systems. Our controller can drive precise time-varying activity levels, automatically identifying the light input required to correct for a nonlinear light-activity relationship. It can deliver custom light levels to each cell within a population to compensate for cell-to-cell variability in optogenetic component expression. Finally, we show the controller can be used to clamp a downstream signaling node at a defined level, even when the node is affected by additional regulatory inputs over time.

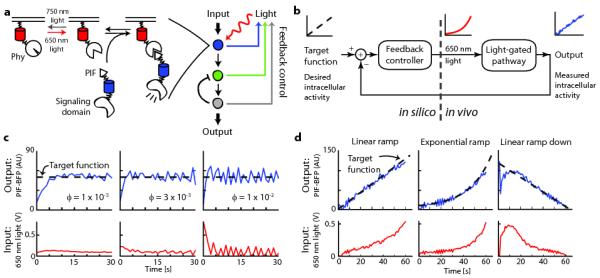

Figure 1. Using feedback control to modulate plasma membrane recruitment of PIF-tagged inputs.

(a) The schematic depicts feedback control of the Phy–PIF optogenetic module. Upon ligation to the small molecule chromophore phycocyanobilin (PCB), membrane-fused, fluorescent PhyB fusion proteins can be used to drive fluorescent PIF-tagged proteins to the plasma membrane by exposure to 650 nm light, and this interaction can be reversed by exposure to 750 nm light. In principle, feedback control can be applied to set the activity state at any downstream node for which live-cell readouts are available. (b) Schematic of the feedback control system. The user specifies a target function, which the controller compares to live-cell measurements to determine the proper light input with which to drive an optogenetically gated intracellular signal. (c,d) The control system can be used to drive user-defined target functions, such as constant membrane binding at various feedback strengths (c), or time-varying membrane binding curves (d). For (b-d), the 650 nm light input (red line), PIF-BFP membrane binding (blue line) and target function (dashed black line) are shown. AU: arbitrary units.

For this work we focused on light-gated recruitment of the Phytochrome Interacting Factor 6 (PIF6) to PhyB (Phy)6, 7 to direct membrane translocation of signaling proteins in mammalian cells (Fig. 1a)8. Phy–PIF modules have been used for light-gated regulation of diverse biological processes, including transcription9, splicing10, and small GTPases in live cells8 and in vitro control of actin assembly11. We applied different ratios of 650 nm and 750 nm light to specific regions of live cells to titrate the recruitment of a fluorescently-tagged PIF fusion protein (PIF- BFP) to the membrane (Online Methods and Supplementary Fig. 1).

We first sought to implement a feedback control system that can generate user-defined dynamics of PIF-tagged protein recruitment to the plasma membrane (Fig. 1b). In this system, the user provides a desired activity timecourse (“target function”) that the controller compares to a measured live cell activity readout (“output”) in real time to determine the appropriate light input to provide to the cell. The Phy–PIF system is well suited for such a strategy because its binding is switchable on a timescale of seconds and PIF membrane translocation can be directly measured in live cells. We based our feedback controller on a widely used architecture, proportional-integral (PI) control, because it can drive precise output levels without requiring a detailed model of the system (often unavailable in biology) and is robust to measurement noise (for a detailed discussion of the controller requirements, development, and implementation see Supplementary Note). After validating the control strategy by applying it to a fitted mathematical model of Phy–PIF-based membrane translocation (Supplementary Figs. 2-5), we implemented it experimentally using custom MATLAB and Micro-Manager12 code (Supplementary Software) to acquire images, measure the membrane PIF recruitment level (by TIRF microscopy), and automatically adjust the 650 nm LED intensity.

We first used the controller to drive constant levels of PIF-BFP membrane recruitment. Before starting the controller we initialized the Phy–PIF system to an “off” state by exposure to 750 nm light. During each control timecourse, the recruitment level was measured and used to update the light input once per second. This strategy was able to drive membrane recruitment of PIF-tagged proteins to desired levels within seconds across a range of feedback strengths and sampling times (Fig. 1c; Supplementary Fig. 6a,b), suggesting that PI control is a robust approach for driving user-defined levels of PIF membrane translocation.

We next tested whether our feedback control system could be extended to generate user-defined time-varying inputs. Using microfluidics, ramped inputs have been used to dissect sensory adaptation2, 3, and oscillating inputs have uncovered feedback loops modulating signal transduction cascades1. However, it has not previously been possible to drive time-varying intracellular signals. We extended our controller to track time-varying target functions using a simple predictive control strategy: by comparing the observed membrane recruitment to the next timepoint’s target level, the controller can anticipate how to change light levels to track a desired output without introducing delay. In this mode, the controller was able to track precise temporal patterns of plasma membrane recruitment including linear and exponential ramps with varying steepness (Fig. 1d; Supplementary Fig. 6c). Even when initialized far from steady state (e.g. with no light input but maximum PIF recruitment), the controller quickly converged on a target curve of PIF recruitment and maintained a faithful trajectory thereafter (Fig. 1d). These results demonstrate that it is possible to drive dynamics of intracellular activity on a timescale of seconds, precision typically restricted to extracellular inputs.

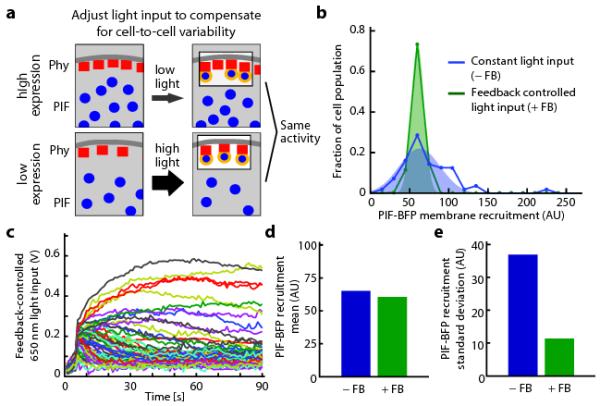

Having shown that our control system can tune activity levels in an individual cell over time, we next asked whether it could be used to compensate for cell-to-cell variability in recruitment due to non-uniform expression of optogenetic components (Fig. 2a). We measured PIF recruitment (Fig. 2b) and Phy–PIF expression levels (Supplementary Fig. 7) in 80 cells to characterize their extent of cell-to-cell variability. Because of variation in Phy–PIF expression, delivering the same light input across the population led to a broad distribution of PIF-BFP membrane recruitment. In contrast, feedback controller tightened the distribution around a desired level of PIF-BFP membrane recruitment (Fig. 2b) by applying appropriate light inputs to each cell (Fig. 2c). This technique decreased the cell population’s standard deviation of PIF recruitment fourfold, while leaving the mean value of PIF recruitment approximately unchanged (Fig. 2c,d). Optogenetic feedback control can be used to tune both the desired recruitment levels in individual cells (Fig. 1) and to reshape population-level distributions of intracellular activity (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Feedback control can decrease cell-to-cell variability in optogenetic response.

(a) The schematic depicts that the same light input applied to cells expressing different levels of optogenetic components will lead to different activity levels. Cell-by-cell light adjustment is necessary to achieve uniform membrane-bound PIF concentrations. (b) Histograms of PIF membrane recruitment under a constant light input (0.2 V 650 nm, 0.1 V 750 nm; blue curve) and during feedback control (green curve). (c) The feedback-controlled voltages applied over time to each cell in b. The light inputs that are required to compensate for cell-cell heterogeneity span a large range of intensities. (d-e) The mean (d) and standard deviation (e) of PIF recruitment in the presence or absence of feedback control for the cell populations shown in b. AU: arbitrary units.

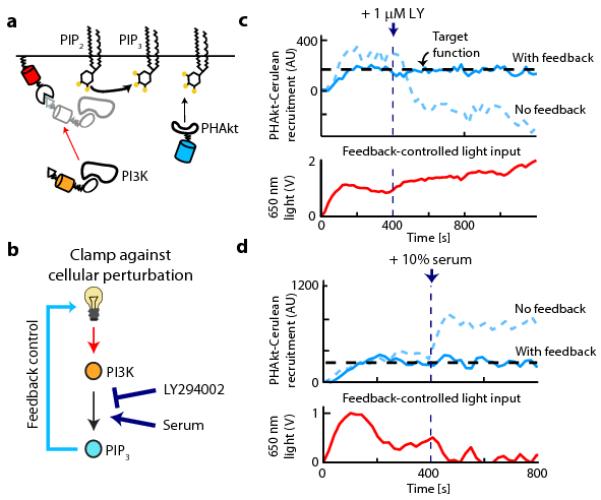

In addition to directly controlling PIF-tagged inputs, feedback control can in principle be applied to signals further downstream for which live-cell readouts are available. Because far more live-cell reporters are available than optogenetic inputs, this technique has the potential to greatly expand the number of signaling steps that can be readily placed under light control. To test this hypothesis we focused on feedback control of the product of an enzymatic reaction in live cells: 3′ phosphoinositides (PIs) generated by phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K). This signaling process has the advantage of live cell biosensors at two nodes: visualizing membrane recruitment of light-gated fluorescent PI3K binding protein (iSH-YFP-PIF), and monitoring PI3K lipid products by the membrane translocation of a fluorescent Akt-PH domain (PHAkt-Cerulean, which binds to PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3)13. We engineered optogenetic control of 3′ PI lipid production using a strategy based on previous successes with chemical dimerizers to drive PI3K membrane recruitment14 (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9). Confirming our hypothesis that feedback control can be applied at sequential signaling nodes, we can clamp upstream recruitment of PIF-tagged proteins (Fig. 1c,d) or downstream signals such as PHAkt recruitment (Supplementary Fig. 9e) in individual cells by providing the appropriate input to the controller.

Figure 3. Feedback control can clamp PIP3 levels against cellular perturbations.

(a) The schematic depicts PI3K recruitment to a membrane target (Phy-mCherry-CAAX) using a fluorescent PIF fusion protein (iSH-YFP-PIF) that constitutively binds endogenous PI3K. 3′ PI lipid levels are assayed by PHAkt-Cerulean recruitment to the plasma membrane. (b) Feedback control can be used to clamp perturbations in upstream signaling nodes by adjusting light levels to compensate for these changes (such as LY294002 based PI3K inhibition or serum-based PI3K activation). (c,d) Upper panels: single-cell timecourses in response to a constant light input (dashed curve) or under feedback control (solid curve). At 400 s, 3′ PI lipid production is perturbed by addition of LY294002, a PI3K inhibitor (c) or serum, a PI3K activator (d). Lower panels: the time-varying light input used by the feedback controller to clamp 3′ PI lipid levels. AU: arbitrary units.

We used optogenetic control of PI3K activity to address a final question: can 3′ PI lipid levels be clamped in cells undergoing the large positive and negative changes in the PI3K activity that may result from positive and negative feedback loops acting to shape pathway dynamics? We spiked in LY294002 (a PI3K inhibitor) or serum (a PI3K activating input) either in the presence or absence of feedback control on PHAkt-Cerulean membrane levels (Fig. 3b). As expected, LY294002 addition decreased 3′ PI lipid levels in cells exposed to a constant light input (Fig. 3c). However, our controller was able to compensate for pharmacological inhibition of PI3K, maintaining constant 3′ PI lipid levels by dramatically increasing the 650 nm light input (Fig. 3c) and thus PI3K recruitment. Similarly, following serum-mediated activation of endogenous PI3K, the controller clamps 3′ PI lipid levels by decreasing the light-gated PI3K input (Fig. 3d; Supplementary Fig. 9e-g).

Here we have combined approaches from optogenetics, control theory, and cell biology to drive precise patterns of intracellular activity in live cells. Our approach suggests several classes of quantitative live-cell experiments. Time-varying inputs, which have been applied extracellularly to dissect sensory signaling cascades, can now be applied to intracellular signals. Applying control on multiple signaling nodes from a single optogenetic input could be used to ‘walk down’ a pathway to identify sources of ultrasensitivity or points of feedback connection. Finally, clamping light-gated inputs against cellular changes in activity could be used to disconnect intracellular feedback circuits without genetic or pharmacological perturbation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all members of the Weiner and Lim labs for helpful comments and discussions; Anselm Levskaya, Arthur Edelstein, and Nico Stuurman for experimental and computational insights; and Alexander Loewer and Hana El-Samad for a critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by a Cancer Research Institute Postdoctoral Fellowship to J.E.T.; an American Cancer Society Fellowship to D.G.; the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and NIH grants GM55040, GM62583, EY016546, and P50GM081879 to W.A.L.; and NIH grant GM084040 and a Searle Scholars Fellowship to O.D.W.

Footnotes

Author Contributions J.E.T. conceived of and implemented the feedback controller. O.D.W. and W.A.L. supervised the project. All authors designed experiments, which were performed by J.E.T. and D.G. J.E.T. analyzed the data. J.E.T., W.A.L. and O.D.W. wrote the paper, which was edited by all authors.

References

- [1].Mettetal JT, Muzzey D, Gomez-Uribe C, van Oudenaarden A. Science. 2008;319:482–484. doi: 10.1126/science.1151582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Muzzey D, Gómez-Uribe CA, Mettetal JT, van Oudenaarden A. Cell. 2009;138:160–171. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Shimizu TS, Tu Y, Berg HC. Molecular Systems Biology. 2010;6:382. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hodgkin AL, Huxley AF, Katz B. J Physiol. 1952;116:424–448. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Visscher K, Schnitzer MJ, Block SM. Nature. 1999;400:184–189. doi: 10.1038/22146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Rockwell NC, Su YS, Lagarias JC. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:837–858. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Khanna R, Huq E, Kikis EA, Al-Sady B, Lanzatella C, Quail PH. Plant Cell. 2004;16:3033–3044. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.025643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Levskaya A, Weiner OD, Lim WA, Voigt CA. Nature. 2009;461:997–1001. doi: 10.1038/nature08446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Shimizu-Sato S, Huq E, Tepperman JM, Quail PH. Nat Biotech. 2002;20:1041–1044. doi: 10.1038/nbt734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Tyszkiewicz AB, Muir TW. Nat Methods. 2008;5:303–305. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Leung DW, Otomo C, Chory J, Rosen MK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:12797–12802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801232105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Edelstein A, Amodaj N, Hoover K, Vale R, Stuurman N. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2010:14.20.01–14.20.17. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1420s92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Haugh JM, Codazzi F, Teruel M, Meyer T. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1269–1280. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.6.1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Suh BC, Inoue T, Meyer T, Hille B. Science. 2006;314:1454–1457. doi: 10.1126/science.1131163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, 3rd, Smith HO. Nat Methods. 2009;6:343–345. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ory DS, Neugeboren BA, Mulligan RC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:11400–11406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Toettcher JE, Gong D, Lim WA, Weiner OD. Methods Enzymol. 2011;497:409–423. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385075-1.00017-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.