Abstract

This study aimed to clarify the possible therapeutic benefit of preferential nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibition and catalytic antioxidant Mn (III) meso-tetrakis (N-n-hexylpyridinium-2-yl) porphyrin (MnTnHex-2-PyP5+) treatment in a rat model of elevated intraocular pressure (EIOP). Rats were randomly divided into different experimental groups which received either intraperitoneal MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ (0.1 mg/kg/day), intragastric NOS inhibitor (S-methylthiourea: SMT; 5 mg/kg/day) or both agents for a period of 6 weeks. Ocular hypertension was induced by unilaterally cauterizing three episcleral vessels and the unoperated eye served as control. Neuroprotective effects of given treatments were determined via electrophysiological measurements of visual evoked potentials (VEP) while retina and vitreous levels of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ were measured via LC-MS/MS. Latencies of all VEP components (P1, N1, P2, N2, P3) were significantly prolonged (p<0.05) in EIOP and returned to control levels following all three treatment protocols. Ocular hypertension significantly increased retinal protein nitration (p<0.001) which returned to baseline levels in all treated groups. NOS-2 expression and nitrate/nitrite levels were significantly greater in non-treated rats with EIOP. Retinal TUNEL staining showed apoptosis in all ocular hypertensive rats. The presented data confirm the role of oxidative injury in EIOP and highlight the protective effect of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ treatment and NOS inhibition in ocular hypertension.

Keywords: ocular hypertension, manganese porphyrin, nitric oxide synthase, SOD mimic, MnTnHex-2-PyP5+

1. Introduction

Experimental studies of induced ocular pressure elevation in nonhuman primates result in typical optic nerve damage as observed in glaucoma (Gaasterland et al., 1978; Quigley and Addicks, 1980). Oxidative stress has been implicated to cause increased intraocular pressure (IOP) by triggering trabecular meshwork (TM) degeneration and thus contributing to alterations in the aqueous outflow pathway (Saccà et al., 2007). Indeed, treatment with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) impairs trabecular meshwork cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix and causes rearrangement of cytoskeletal structures (Zhou et al., 1999). Trabecular meshwork cells show reduced sensitivity to H2O2 when cells are treated with timolol (Miyamoto et al., 2009), a non-selective beta-adrenoceptor antagonist currently used as an ocular preparation for the treatment of glaucoma (Nieminen et al., 2007). Timolol has been shown to induce the expression of peroxiredoxin-2 (Miyamoto et al., 2009), which functions as an antioxidant enzyme such as catalase and glutathione-dependent peroxidase (Hall et al., 2009). It has also been demonstrated that oxidative DNA damage is significantly greater in TM cells of glaucoma patients compared to controls (Izzotti, 2003). Moreover, in vivo studies in humans have shown that both IOP increase and visual field damage are significantly related to the amount of oxidative DNA damage (Saccà et al., 2005). Similarly, severity of optic nerve damage in eyes with primary open angle glaucoma is correlated with changes in the TM (Gottanka et al., 1997).

Retinal oxidative injury occurring in models of elevated intraocular pressure or in normal tension glaucoma also directly damage the retinal ganglion cell layer, leading to glaucomatous optic neuropathy (GON) (Tezel, 2006). Free radical injury has been reported to cause caspase independent cell death in retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) in vitro. (Tezel and Yang, 2004). Furthermore, many retinal proteins exhibit oxidative modifications in experimental glaucoma, which may lead to important structural and functional alterations (Tezel et al., 2005).

Ocular tissues and fluids contain antioxidants that play a key role in protecting against oxidative damage. However, specific activity of a major antioxidant enzyme, superoxide dismutase (SOD), demonstrates an age-dependent decline in normal human trabecular meshwork (De La Paz and Epstein, 1996). Similarly, plasma glutathione levels assessed in 21 patients with newly diagnosed primary open-angle glaucoma and 34 age- and gender-matched control subjects revealed that glaucoma patients exhibited significantly lower levels of reduced and total glutathione than did control subjects (Gherghel et al., 2005). A recent study showed that astaxanthin (ASX), a naturally occurring carotenoid pigment and a powerful biological antioxidant, alleviated retinal injury induced by elevated intraocular pressure (Cort et al., 2010).

Increased expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (NOS-2) in rat models of chronic ocular hypertension is consistent with the involvement of nitric oxide (•NO) cytotoxicity in elevated IOP (EIOP) (Shareef et al., 1999). Physiological studies demonstrate that diffusion-limited reaction of ˙NO with superoxide (O2˙.−) leads to the formation of highly oxidizing and nitrating species peroxynitrite (ONOO-) (Ferrer-Sueta and Radi, 2009). Indeed, the presence of nitrotyrosine (NO2Tyr) in optic nerve heads supports the formation of reactive nitrogen species that may contribute to RGC death associated with increased IOP (Liu and Neufeld, 2000; Shareef et al., 1999). Based on the role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in the pathogenesis of glaucoma (Aslan et al., 2008) and the relevance of antioxidant protection against retinal neurodegeneration, this study aimed to evaluate NOS-2 inhibition and the therapeutic potential of a newly designed metalloporphyrin-based antioxidant, Mn (III) meso-tetrakis (N-nhexylpyridinium-2-yl) porphyrin (MnTnHex-2-PyP5+) in rats with increased intraocular pressure (Batinic-Haberle et al., 2010).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

All experimental protocols conducted on rats were performed in accordance with the standards established by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Akdeniz University Medical School. Male Wistar rats weighing 350–450 g were housed in stainless steel cages and given food and water ad libitum. Animals were maintained at 12 hours light -dark cycles and a constant temperature of 23 ± 1°C at all times. Rats were randomly divided into different experimental groups (n=10) which received either intraperitoneal (i.p) MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ (0.1 mg/kg/day), intragastric moderately selective NOS-2 inhibitor (S-methylthiourea: SMT; 5 mg/kg/day; Sigma Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) or both agents for a period of 6 weeks. There were no signs of alopecia or ulceration on the rat skin during the total experimental period. Control group rats received equal volumes of intragastric and i.p. distilled water.

2.2. Synthesis of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+

MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ was prepared as described in details (Keir et al., 2010). The quaternization of H2T-2-PyP5+ (Frontier Scientific) was performed with n-hexyl p-toluenesulfonate (TCI America). Upon completion, the metal-free ligand was washed between water and chloroform. From aqueous phase it was precipitated as PF6− salt. This salt was thoroughly washed with diethylether and dissolved in acetone. A Cl− salt of H2TnHex-2-PyP5+ was then precipitated from acetone and metallated with MnCl2. The MnTnHex-2-PyPCl5 was characterized by thin-lyer chromatography on silica gel plates using 8:1:1 acetonitrile:KNO3-saturated H2O:H2O as mobile phase. It was also analyzed by elemental analysis and mass spectrometry.

2.3. Rat model of elevated intraocular pressure

Intraocular pressure was elevated in rats by cauterizing three episcleral vessels, as previously described (Sawada and Neufeld, 1999; Shareef et al., 1995). Briefly, rats were anesthetized intraperitoneally with a mixture of ketamine (25 mg/kg, Richter Pharma AG, Wels, Austria) and xylazine hydrochloride (5 mg/kg, Alfasan International B.V., Woerden, Holland). Episcleral vessels were exposed by incising the overlying conjunctiva and cauterized via an ophthalmic cautery. Pain relief was provided to all rats via intramuscular (im) injections oftramadol hydrochloride (2 mg/kg; CONTRAMAL, Abdi Ibrahim, Istanbul, Turkey), given twice with 12-hr intervals, following the first day of post-operative treatment. Intraocular pressure was measured before surgery and every week after surgery over a 6-week period. A handheld tonometer (XL-Tonopen, Mentor O and O, Norwell, MA, USA) was used to measure IOP in rats under light anesthesia. It has previously been reported that all anesthetics result in significant reduction in measured IOP when compared with the corresponding awake IOP (Jia et al., 2000). However, it was not possible to do the measurements on awake animals. Intraocular pressure measurements were performed as described in the instruction manual of the tonometer. The mean IOP of 5–10 consecutive measurements were recorded. Operated eyes served as EIOP while the unoperated eyes were control. At the end of the 6 week experimental period, visual evoked potentials were recorded between 10.00 AM and 2.00 PM and animals were sacrificed the next day under anesthesia by exsanguination via cardiac puncture. Enucleated globes were divided into eight groups of 10 eyes each as follows; control, EIOP, SMT treated, SMT treated EIOP, MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ treated, MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ treated EIOP, SMT + MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ treated and SMT + MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ treated EIOP.

2.4. Visual evoked potential recordings

Visual evoked potentials were recorded with stainless steel subdermal electrodes (Nihon Kohden NE 223 S, Nihon Kohden Corporation, Tokyo 161, Japan) under ether anesthesia as previously described (Akpinar et al., 2007). The reference and active electrodes were placed 0.5 cm in front of and behind bregma, respectively. The active electrode was also placed 0.4 cm lateral to the midline over area 17 of visual cortex. A ground electrode was placed on the tails of animals. After 5 min of dark adaptation, a photic stimulator (Nova-Strobe AB, Biopac System Inc., Santa Barbara, CA 93117, USA) at the lowest intensity setting was used to provide the flash stimulus at a distance of 15 cm, which allowed lighting of the entire pupilla from the temporal visual field. Repetition rate of flash stimulus was 1 Hz and flash energy was 0.1 J. VEP recordings from both right and left were obtained, and throughout the experiments the eye not under investigation was occluded by appropriate black carbon paper and cotton. Body temperature was maintained between 37.5°C and 38.0°C via a heating pad and monitored with a rectal thermometer probe (Havard Apparatus Homoeothermic Blanket Control Unit, Havard Apparatus Ltd. Kent, United Kingdom).

The averaging of 100 responses was accomplished with the averager of Biopac MP100 data acquisition equipment (Biopac System Inc., Santa Barbara, CA 93117, USA). Analysis time was 300 ms. The frequency bandwidth of the amplifier was 1Hz–100 Hz. The gain was selected 20 μV/div. The sampling rate of the VEP recording was 2000 samples. The microprocessor was programmed to reject any sweeps contaminated with larger artifacts, and at least two averages were obtained to ensure response reproducibility. Peak latencies of the components were measured from the stimulus artifact to the peak in milliseconds. Amplitudes were measured as the voltage between successive peaks. Measurements were made on three positive and two negative potentials which are seen in all groups.

2.5. Measurement of Retina and Vitreous Levels of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+

At the end of the 6 week experimental period, retinas harvested from enucleated globes were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until analyzed. Measurement of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ was performed after retinas were harvested. Sample preparation; in 2 mL polypropylene screw-cap vial, 150 μl of sample (150 μl of vitreous liquid or 150 μl of 50 mg tissue + 100 μl water homogenate) and 10 μl of 100 nM internal standard solution in water was added and mixture was left at room temperature for 10 min. As internal standard the heptyl analog, Mn (III) meso-tetrakis (N-n-heptylpyridinium-2-yl) porphyrin, MnTnHep-2-PyP5+ was used (Kos et al 2009). After 300 μl of 1% acetic acid in methanol was added, the mixture was vigorously agitated (Fast Prep, 40 sec, speed 6) and left 15 min at −20 °C. After centrifugation at 16,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C, 300 μl of supernatant was transferred into 1.5 mL conical polypropylene vial, added 300 μl of 0.1% heptafluorobutyric acid (HFBA) in 5% acetonitrile, 95% water, mixture vortexed, and centrifuged at 16,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. 500 μl of supernatant (vitreous liquid method) or 50 μl (retina method) was injected into LC/MS/MS system. LC conditions; Shimadzu 20A series HPLC; column: Phenomenex 4 × 3 mm C18 guard cartridge used as analytical column; column temperature: 35°C; mobile phase A: 0.01% heptafluorobutyric acid (HFBA) in 95:5 H2O:acetonitrile; mobile phase B: acetonitrile; elution gradient: 0–0.2 min 0–90% B, 0.2–0.7 min 90% B, 0.7–0.75 min 90–0% B; run time: 4 min. MS/MS conditions; Applied Biosystems MDS Sciex 4000 Q Trap ESI-MS/MS was optimized for the following MRM transitions (parent ion [MnP5+ + 3HFBA−]2+/2): MnTnHex-2-PyP5+, m/z 825.5/611.5 (analyte) and MnTnHep-2-PyP5+, m/z 853.5/639.5 (internal std.)

Calibration samples for analysis in retina were prepared by adding known amounts of pure MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ into mouse muscle homogenate (10 – 300 nM range). For analysis in vitreous liquid, phosphate buffered saline (PBS) was used as a matrix (1–10 nM range).

2.6. Immunohistochemical Staining

Enucleated globe materials were fixed in 10% buffered formalin solutions and incised in transverse plain just from the center of the globe to obtain two equal parts. Fixed tissues were washed in phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4), embedded in paraffin and cut into 4-μm sections. For peroxidase staining, sections were deparaffined, rehydrated and washed with Tris buffered saline. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubating tissue sections with 3% hydrogen peroxide for five minutes prior to application of the primary antibody. Primary antibody incubations were for 60 min at 25°C using rabbit polyclonal anti-nitrotyrosine (NO2Tyr) (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor MI, 10 mg/ml). After sections were washed they were immunostained with an avidin-biotin complex kit (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) followed by hematoxylin counterstaining. Negative controls were performed by replacing the primary antibody with nonimmune serum followed by immunoperoxidase staining. Presence of a red-brown colored end-product in the cytoplasm was indicative of positive staining. Counterstaining with hematoxylin resulted in a pale to dark blue coloration of cell nuclei. All stained tissue sections were visualized via light microscopy (Olympus IX81, Tokyo, Japan).

2.7. Quantitation of Nitrotyrosine in the Retina

Nitrotyrosine content in the retina was measured via ELISA using a commercial kit (Northwest life Science, Vancouver, WA). Antigen captured by a solid phase monoclonal antibody (nitrated keyhole limphet hemocyanin raised in mouse) was detected with a biotin-labeled goat polyclonal anti-nitrotyrosine. A streptavidin peroxidase conjugate was then added to bind the biotinylated antibody. A tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate was added and the yellow product was measured at 450 nm. A standard curve of absorbance values of known nitrotyrosine standards at 450 nm was plotted as a function of the logarithm of nitrotyrosine standard concentrations using the GraphPad Prism Software program for windows version 5.03 (GraphPad Software Inc). Nitrotyrosine concentrations in the samples were calculated from their corresponding absorbance values via the standard curve.

2.8. TUNEL analysis

Apoptotic cells were visualized with the terminal deoxynucleotide transferase (TdT) FragEL DNA fragmentation kit (Oncogene, Boston, MA) analogous to TdT mediated nick endlabeling. Dark brown cells with pyknotic nuclei were indicative of positive staining for apoptosis, whereas green to greenish color signified a nonreactive cell. To obtain a quantitative standard for apoptotic cell death within the different experimental group's morphometric analysis was performed on all retinal sections.

2.9. SDS-PAGE and Western Blot Analysis

Retina was harvested from enucleated globes and homogenized in 2 ml ice-cold homogenizing buffer (50mM K2HPO4, 80 μM leupeptin (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany), 2.1 mM Pefabloc SC (SERVA, Heidelberg, Germany), 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma-Aldrich), 1μg/ml aprotinin (SERVA; pH 7.4). Homogenates were centrifuged (40,000 g, 30 mins, 4°C) and supernatants were stored at −80°C until analyzed. For Western blot analysis, tissue proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. A rabbit polyclonal antibody against NOS-2 (1:100 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was used for immunoblot analysis. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000 dilution; Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, CA) was used as a secondary antibody, and immunoreactive proteins were visualized by chemiluminescence via ECL reagent (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, England). Proteins separated by SDS-PAGE were also visualized by Electro-Blue Staining solution (Qbiogene, Heidelberg, Germany) to confirm equal protein loading in each lane (Cort et al., 2010).

2. 10. Nitrite and nitrate assay

Samples were transferred to an ultrafiltration unit and centrifuged through a 10 kDa molecular mass cut-off filter (Centricon, Millipore Corporation) for 1 h to remove protein. Analyses of tissue homogenates were performed in duplicate via the Greiss reaction using a colorometric assay kit (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany). Protein concentrations were measured at 595 nm by a modified Bradford assay by using Coomassie Plus reagent with bovine serum albumin as a standard (Pierce Chemical Company, Rockford, IL).

2. 11. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS and Sigma Stat software programs for windows. Significance levels were set at p< 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Intraocular pressure levels

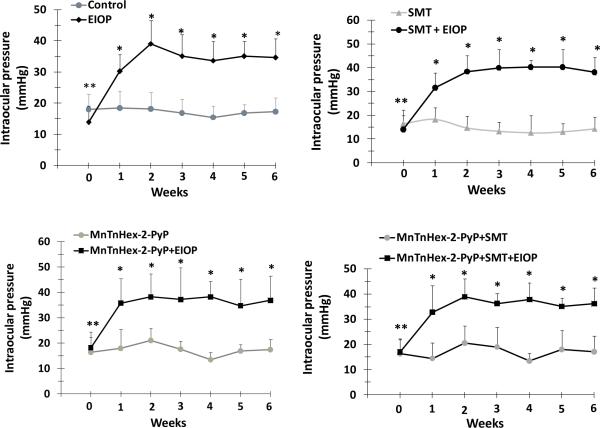

Intraocular pressure of eyes in which vessels were cauterized is represented as EIOP, and is compared to the contralateral eyes. Average IOP (mean ± SD) measured in non-cauterized eyes was 17.3 ± 3.51 mm Hg for the control (n=10) group. An increase of about 15–20 mm Hg was observed in cauterized eyes compared to respective controls with an average value of 31.3 mm Hg for EIOP, n=10. Recorded IOP from cauterized eyes remained elevated over the experimental period. (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Intraocular pressure measurements of eyes. Values represent mean ± SD, n=10. MnTnHex-2-PyP, Mn (III) meso-tetrakis (N-hexylpyridinium-2-yl) porphyrin; SMT, S-methylthiourea; EIOP, elevated intraocular pressure. Statistical analysis was performed by two way analysis of variance with all pairwise multiple comparison procedures done by Tukey test. Week 0 represents IOP measurements before vessels were cauterized. **, p< 0.001 compared to week 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 in EIOP groups. *, p< 0.001 compared to unoperated eyes within the same treatment group.

3.2. Retina and Vitreous Levels of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+

MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ were detected in both retinal tissue and vitreous liquid. Measured levels in the retina were ~70 fold higher compared to the vitreous. MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ levels found were 201 ng/g (~200 ng/mL) in retina tissue and 2.9 ng/mL in vitreous liquid.

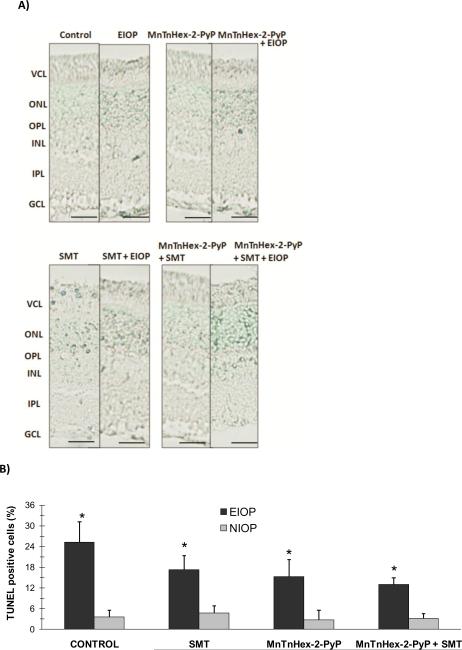

3.3. Apoptosis

Figure 2A shows representative photomicrographs of retinal TUNEL staining from each of the four groups. Apoptotic cells are seen in the GCL, outer and inner nuclear layers of all experimental groups. TUNEL-positive cells were also quantified in the retina (figure 2B). Retinal TUNEL staining showed significant increase in apoptosis in all EIOP groups compared to unoperated controls with normal intraocular pressure (NIOP). Although not statistically significant, treatment with either a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor (S-methylthiourea; SMT), MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ or both decreased the percent of apoptotic cells in ocular hypertensive eyes compared to the control group. Still, it is important to note that with the small n, a Type 2 statistical error is possible.

Figure 2.

A) TUNEL staining of the retina. Photomicrographs of representative rat are shown from each of the experimental groups. Apoptotic cells are seen in the ganglion cell layer (GCL), photoreceptor cell layer (VCL) outer (ONL) and inner (INL) nuclear layers of the retina. Bars 50 μm. B) Percent of apoptotic cells in the retina. Values are given as mean ± SD. Cells present in 5 high powered fields (HPF, 40×) were counted in each section (n=3) and the ratio of apoptotic cells was calculated as the percent of the whole cell number. Statistical analysis was performed by two way analysis of variance with all pairwise multiple comparison procedures done by Tukey test. *, p< 0.01 compared to NIOP within the same treatment group. MnTnHex-2-PyP, Mn (III) meso-tetrakis (N-n-hexylpyridinium-2-yl) porphyrin; SMT, S-methylthiourea; EIOP, elevated intraocular pressure.

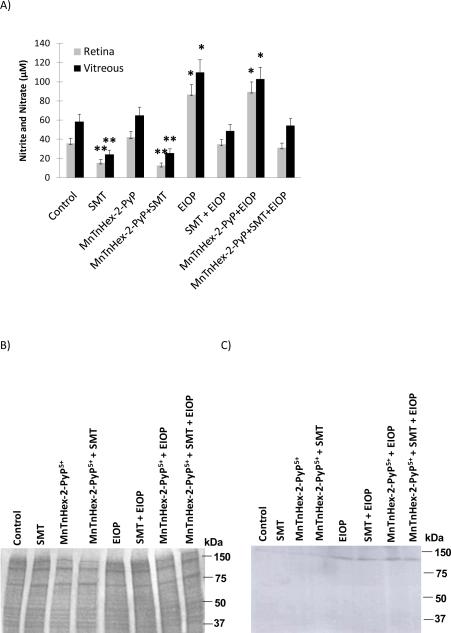

3.4. Vitreous and retinal tissue homogenate nitrite and nitrate content

Vitreous and retinal tissue homogenate nitrite (NO2−) and nitrate (NO3−) concentrations are shown in figure 3A. Vitreous NO2− + NO3− levels (mean ± SEM, n= 5–6) measured in EIOP and MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ + EIOP groups (103 ± 12.3 and 110 ± 13.0 μM, respectively) were significantly greater (p< 0.05) compared to other experimental groups (Control, 58.2 ± 7.82; SMT, 24.2 ± 4.42; MnTnHex-2-PyP5+, 65 ± 8.5; MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ + SMT, 25.6 ± 4.56; SMT + EIOP, 48.9 ± 6.89 and MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ + SMT+ EIOP, 54.2 ± 7.42 μM). Retina NO2− + NO3− levels affirmed significantly increased (p<0.05) levels of nitric oxide generation in EIOP with measured values as follows: EIOP, 86.8± 10.68; MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ + EIOP, 89.3 ± 10.93; Control, 35.6 ± 5.56; SMT, 15.5 ± 3.55; MnTnHex-2-PyP5+, 42 ± 6.2; MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ + SMT, 12.3 ± 3.23; SMT + EIOP, 34.6 ± 5.46 and MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ + SMT+ EIOP, 31.2 ± 5.12 μM.

Figure 3.

A) Vitreous and retinal tissue homogenate nitrite and nitrate content. Values are mean ± SEM, n= 5–6. Statistical analysis was done via Kruskal-Wallis one way analysis of variance on ranks with all pairwise multiple comparison procedures carried out via Dunn's Method. **, p< 0.05, compared to all experimental groups except for SMT treated. *, p < 0.05, compared to all experimental groups except for EIOP and MnTnHex-2-Pyp+EIOP. MnTnHex-2-PyP, Mn (III) meso-tetrakis (N-n-hexylpyridinium-2-yl) porphyrin; SMT, S-methylthiourea; EIOP, elevated intraocular pressure. B) Coomassie blue staining of retinal tissue C) Representative blot of NOS-2 western blot analysis. Mn(III) meso-tetrakis (N-n-hexylpyridinium-2-yl) porphyrin; SMT, S-methylthiourea; EIOP, elevated intraocular pressure.

Treatment with SMT caused a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in both retinal and vitreous NO2− + NO3− levels under NIOP as compared to control and MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ treated groups. Treatment with SMT under EIOP also decreased retinal and vitreous NO2− + NO3− to baseline control levels.

3.5. Western blot analysis of NOS2

Coomassie based staining of retinal tissue proteins that were separated for Western blot analysis shows equal protein loading in each lane (figure 3B). Retinal homogenates analyzed by immunoblotting with rabbit polyclonal antibody against NOS-2 revealed an immunodetectable 130 kDa protein band present in all EIOP groups (figure 3C). This data validates the significant increase in nitrite and nitrate levels measured in EIOP and MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ + EIOP groups. Although there is increased NOS-2 protein in MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ + SMT + EIOP and SMT + EIOP groups, this is not accompanied by increased nitrate and nitrite levels attributable to treatment with the NOS-2 inhibitor SMT.

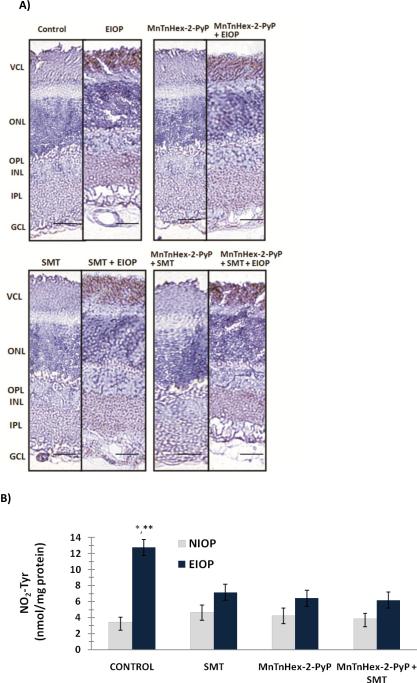

3.6. Immunostaining and quantitation of nitrotyrosine in the retina

Nitrotyrosine positive staining was observed throughout the outer plexiform layer (OPL), inner plexiform layer (IPL) and ganglion cell layer (GCL) in EIOP groups (figure 4A). The photoreceptor cell layer (VCL) also showed diffuse NO2Tyr immunostaining in all eyes with EIOP. Nitrotyrosine content measured in the retina of experimental groups is shown in figure 4B (mean ± SD, n=5–6). Formation of protein NO2Tyr was significantly increased in EIOP (12.75 ± 1.7 nmol/mg protein) (p<0.001) as compared to other experimental groups. Treatment with either MnTnHex-2-PyP5+, SMT or both decreased retinal NO2Tyr content in EIOP. No statistical significance was observed in NO2Tyr levels among EIOP groups treated with either, MnTnHex-2-PyP5+, SMT or both (6.43 ± 0.93, 7.15 ± 0.96 and 6.18 ± 0.87 nmol/mg protein, respectively). Likewise, no significant difference was found in NO2Tyr levels measured in treated EIOP groups as compared to control (3.46 ± 0.61 nmol/mg protein).

Figure 4.

A) Immunostaining of nitrotyrosine in the retina. Retinal photomicrographs of representative rat are shown from each of the four groups. GCL, ganglion cell layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; VCL, photoreceptor cell layer. NOS-2 positive staining was observed throughout the outer plexiform layer (OPL), inner plexiform layer (IPL) and ganglion cell layer (GCL) in EIOP groups. Bars 50 μm. B) Quantitation of nitrotyrosine in the retina. Values are mean ± SD, n=5–6. Statistical analysis was performed by two way analysis of variance with all pairwise multiple comparison procedures done by Tukey test. * and **, p<0.001 compared to normal intraocular pressure (NIOP) control and all other elevated intraocular pressure (EIOP) groups. MnTnHex-2-PyP, Mn (III) meso-tetrakis (N-nhexylpyridinium-2-yl) porphyrin; SMT, S-methylthiourea; EIOP, elevated intraocular pressure.

3.7. Visual evoked potentials

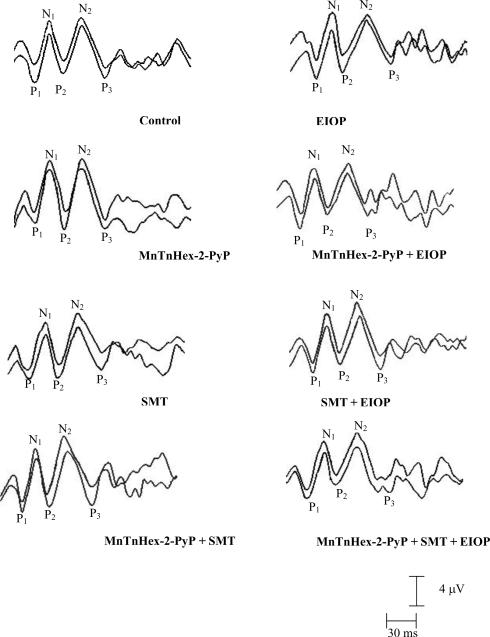

Representative waveforms of VEPs for all groups are presented in Figure 5. Differences of VEP parameters were analyzed by ANOVA. The means and standard deviations of peak latencies of VEP components of all groups, and the results of the statistical analysis are shown in Table 1. The mean latencies of P1, N1, P2, N2 and P3 components were significantly prolonged in eyes with EIOP compared to all experimental groups (p<0.05). Treatment with either, MnTnHex-2-PyP+5, SMT or both decreased all VEP components in eyes with EIOP as compared to non treated eyes (table 1). No significant differences were observed in amplitudes of VEP among experimental groups (table 2).

Figure 5.

RepresentatIve waveforms of VEPs in all experimental groups. The two tracings in each panel are the overlay of representative VEP recordings from each group. The three positive peaks are depicted as P1, P2, P3 and two negative peaks are labeled as N1, N2. MnTnHex-2-PyP, Mn (III) meso-tetrakis (N-n-hexylpyridinium-2-yl) porphyrin; SMT, S-methylthiourea; EIOP, elevated intraocular pressure.

Table 1.

Peak latencies of each VEP component from all experimental groups.

| Groups | P1 (ms) | N1 (ms) | P2 (ms) | N2 (ms) | P3 (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 21.7 ± 1.1 | 37.1 ± 2.7 | 50.2 ± 1.8 | 70.2 ± 2.5 | 92.3±2.6 |

| EIOP | 25.5 ± 2.2* | 41.4 ± 1.9* | 55.3 ± 2.2* | 76.6 ± 4.5* | 100.5 ± 3.1* |

| MnTnHex-2-PyP | 21.9 ± 1.8 | 37.5 ± 2.7 | 50.2 ± 4.4 | 67.9 ± 3.1 | 92.5 ± 2.4 |

| MnTnHex-2-PyP+EIOP | 22.2 ± 1.4 | 38.2±3.1 | 51.4 ± 4.8 | 71.7 ± 4.6 | 93.2 ± 4.0 |

| SMT | 21.1 ± 2.1 | 37.9±3.6 | 50.7 ± 2.9 | 70.2 ± 5.3 | 92.1 ± 3.7 |

| SMT + EIOP | 22.1 ± 2.1 | 38.9±3.6 | 51.7 ± 2.9 | 72.2 ± 5.3 | 93.7 ± 4.7 |

| MnTnHex-2-PyP+SMT | 21.7 ± 1.5 | 36.1 ± 1.9 | 49.6 ± 2.7 | 67.3 ± 3.4 | 92.9 ± 2.6 |

| MnTnHex-2-PyP+SMT + EIOP | 22.9 ± 2.1 | 38.6 ± 2.9 | 51.8 ± 4.8 | 71.1 ± 5.2 | 93.8 ± 5.3 |

Values are mean ± SD and n=10. Latencies and peak-to-peak amplitudes of each VEP component was analyzed by two way analysis of variance with all pairwise multiple comparison procedures done by Tukey test.

p<0.05 compared to all experimental groups.

MnTnHex-2-PyP, Mn (III) meso-tetrakis (N-n-hexylpyridinium-2-yl) porphyrin; SMT, S-methylthiourea; EIOP, elevated intraocular pressure.

Table 2.

Peak-to-peak amplitude of each VEP component.

| Groups | P1N1 (μV) | N1P2 (μV) | P2N2 (μV) | N2P3 (μV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 6.0 ± 2.2 | 5.4 ± 2.5 | 5.5 ± 2.0 | 5.7 ± 1.7 |

| EIOP | 5.9 ± 1.8 | 4.9 ± 1.4 | 6.4 ± 2.0 | 4.9 ± 1.5 |

| MnTnHex-2-PyP | 6.2 ± 2.1 | 5.3 ± 1.9 | 6.4 ± 2.5 | 7.1 ± 1.8 |

| MnTnHex-2-PyP+EIOP | 5.7 ± 2.2 | 4.3 ± 1.2 | 5.7 ± 2.1 | 5.4 ± 1.7 |

| SMT | 5.4 ± 1.2 | 4.6 ± 1.5 | 5.8 ± 2.1 | 4.9 ± 1.3 |

| SMT + EIOP | 5.3 ± 1.8 | 4.2 ± 1.1 | 6.0 ± 1.8 | 5.2 ± 1.7 |

| MnTnHex-2PyP+SMT | 7.0 ± 1.5 | 5.3 ±1.5 | 6.7 ± 2.4 | 5.9 ± 2.0 |

| MnTnHex-2-PyP+SMT + EIOP | 4.6 ± 1.8 | 4.3 ± 1.8 | 5.7 ± 1.4 | 6.2 ± 2.4 |

Values are mean ± SD and n=10. MnTnHex-2-PyP, Mn (III) meso-tetrakis (N-n-hexylpyridinium-2-yl) porphyrin; SMT, S-methylthiourea; EIOP, elevated intraocular pressure.

4. Discussion

This study examined the effect of a lipophilic cationic Mn porphyrin, MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ and preferential NOS-2 inhibition in rats with increased IOP. To accomplish intraocular pressure elevation, episcleral vessels of the eye were cauterized as previously described (Sawada et al., 1999). A 1.8-fold increase in IOP was observed in operated eyes following surgery, and persisted over the experimental period. The measured increase in IOP compared well to previous levels reported in rats (Shareef et al., 1995; Aslan et al., 2006). The given i.p. dose of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ (0.1 mg/kg/day) was sufficient for the compound to be observed in both retinal and vitreous tissue via LC/ESI-MS/MS. Higher levels detected in the retina can be attributed to the lipophilicity of the given compound.

The present study showed that experimentally-induced ocular hypertension resulted in prolongation of VEP latencies and that MnTnHex-2-PyP+5, SMT or both decreased all VEP latencies in eyes with EIOP as compared to non treated eyes (table 1). Since all given treatments were systemic, the operated eyes served as EIOP while the unoperated eyes were control. The amplitudes and latencies of VEP components found in our laboratory are generally in agreement with those found in other laboratories (Silver et al., 1995). Considering that VEPs are a sensitive and reliable method to evaluate the earliest changes in the visual system (Lehman and Harrison, 2002), these results indicate that elevated IOP markedly affects the visual system. The changes in the initial portion of the VEP waveform suggest altered function in the “front end” of the visual system (Herr et al., 1995; Schroeder et al., 1991). The prolongation of late components (N2, P3) of VEPs may also reflect altered cortical processing of the visual stimulus (Herr et al., 1995). From our findings (Akpinar et al., 2007) together with previous results (Herr et al., 1995; Schroeder et al., 1991), it could be concluded that glaucoma-induced increase in VEP latencies may be due to delayed input to the visual cortex and/or alterations at the cortical level.

Prolonged latencies and no apparent difference in amplitudes observed in VEP components following intraocular pressure elevation (tables 1 and 2) are in agreement with previous studies which have reported the presence of an abnormal VEP pattern in patients with ocular hypertension (OHT) (Howe and Mitchell, 1986; Towle et al., 1983). In OHT patients, delayed latencies have been recorded with preservation of amplitudes (Graham and Klistorner, 1998). Peroxidation damage has been shown to increase VEP latencies without altering the recorded amplitudes (Derin et al., 2009). In particular, oxidation of lipids found abundantly in cell membranes can lead to altered membrane structure and change neuronal functions (Bazan et al., 2005).

The observed increase in NOS-2 protein and increased levels of NO2− and NO3− is consistent with the involvement of nitric oxide (NO) cytotoxicity in EIOP (Shareef et al., 1999). Reported studies demonstrate the presence of NOS-2 in glaucomatous optic nerve heads with consistent staining of NO2Tyr, indicating that reactive nitrogen species may contribute to retinal ganglion cell death associated with increased intraocular pressure (Liu and Neufeld, 2000; Shareef et al., 1999). Due to diffusion-limited reaction of ˙NO with superoxide (O2˙.−), the highly oxidizing species peroxynitrite (ONOO−) gets formed in vivo (Ferrer-Sueta and Radi, 2009). Peroxynitrite was presumably involved in NO2Tyr formation and therefore in cytotoxicity. Indeed, pharmacological studies have shown that inhibition of NOS-2 by aminoguanidine provides neuroprotection to retinal ganglion cells in a rat model of chronic glaucoma (Neufeld et al., 1999). Treatment with MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ did not affect levels of NO2− and NO3−3, as it does not inhibit NOS while SMT does. However, the oxidative damage of proteins resulting in NO2Tyr formation is predominantly due to the action of ONOO−. MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ is among the most potent ONOO− scavengers (Batinic-Haberle et al., 2010) and thus was able to decrease protein NO2Tyr to control levels (figure 4B). This action, along with its ability to eliminate O2˙− contributes to its effect upon the suppression of apoptotic pathways (figure 2). While statistical significance has not been reached with apoptosis experiments there was a trend towards the larger effect of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ which indicates that perhaps O2˙− and ONOO− might both play a role in the observed cell death.

The major mechanism of visual loss in glaucoma is retinal ganglion cell apoptosis, leading to thinning of the inner nuclear and nerve fiber layers of the retina and axonal loss in the optic nerve (Fechtner and Weinreb, 1994). In animal models of ocular hypertension, elevated IOP augments apoptosis in retinal cells (Aslan et al., 2006) suggesting that nitrative stress exacerbates disease progression in clinical conditions accompanied by ocular degeneration (Aslan et al., 2007; Yücel et al., 2006). Nitric oxide-mediated cytotoxicity and the capacity of NO to induce apoptosis have been documented in macrophages (Sarih et al., 1993), astrocytes (Hu and Van Eldik, 1996), and neuronal cells (Heneka et al., 1998). Although the mechanisms of NO-mediated apoptosis are not clearly elucidated, the induction of apoptosis by NO can be the result of DNA damage which in turn activates p53 that has been reported to cause apoptosis (Kim et al., 1999). Ocular reactive oxygen and nitrogen species formation are important regulators of apoptosis which can be induced by two major pathways. The extrinsic pathway involves binding of TNF-α and Fas ligand to membrane receptors leading to caspase-8 activation, while the intrinsic pathway participates in stress-induced mitochondrial cytochrome c release (Aslan et al., 2008).

Nitration of tyrosine residues has been detected in multiple species, organ systems, and cell types during both acute and chronic inflammation (Ischiropoulos et al., 2005). The existence of multiple distinct, yet redundant pathways for tyrosine nitration underscores the potential significance of this process in inflammation and cell signaling. This post-translational protein modification is thus a marker of oxidative injury that is frequently linked to altered protein function during inflammatory conditions (Ischiropoulos et al., 2005; Aslan et al., 2003). Previous reports have revealed the occurrence of oxidative stress in glaucomatous optic nerve damage (Ferreira et al., 2004; Izzotti et al., 2003). Elevated expression of NOS-2 in this disease implies the formation of secondary species capable of nitration reactions.

There are several in vivo studies that have utilized MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ to suppress oxidative stress injury (Spasojević et al., 2011; Batinić-Haberle et al., 2010). To our knowledge, this is the first report showing the beneficial effect of this porphyrin in ocular hypertension. MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ has drawn attention because it is 13,500-fold more lipophilic than widely used MnTE-2-PyP5+, while possessing the same ability to eliminate O2.˙− (Batinic-Haberle et al., 2002) and ONOO− (Ferrer-Sueta et al., 2003). Due to its lipophilicity MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ was around 30-fold more efficient in allowing SOD deficient E. coli to grow aerobically than MnTE-2-PyP5+ (Okado-Matsumoto et al., 2004). Lipophilic MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ distributes 12-fold more in brain than MnTE-2-PyP5+. At 30 min after intravenous (i.v.) injection, plasma to brain ratios were 8:1 for MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ and 100:1 for MnTE-2-PyP5+ (Sheng et al., 2010). Thus MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ was effective in a middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model at significantly lower doses of 0.45 mg/kg/day, delivered for a week (Sheng et al., 2010). Recent data point to the additional and possibly major advantage of MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ which may account for up to 120-fold enhanced efficacy in vivo when compared to hydrophilic MnTE-2-PyP5+. Saccharomyces cerevisiae study showed that MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ accumulates >90% in mitochondria relative to cytosol (Spasojevic et al., 2011).

The data provided thus far indicate that the most potent Mn porphyrins studied in vivo are very effective in decreasing levels of oxidant species (Batinic-Haberle et al., 2010). But there is also growing evidence that porphyrins may do more than quench oxidant production (Tse et al., 2004). For example, porphyrins have been shown to inactivate transcription factors AP-1, SP-1, NF-κB, HIF-1, either through eliminating reactive species or through directly oxidizing them (Tse et al., 2004) therefore affecting expression of corresponding genes. The redox properties that allow MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ to eliminate O2˙− makes it also a potentially efficient peroxynitrite scavenger, as well as likely scavengers of peroxyl radicals and alkoxyl radicals (Batinić-Haberle et al., 2010). Whatever mechanism is in action, antioxidants would also decrease the levels of oxidatively-modified biological molecules like nitrated lipids and nitrosated proteins involved in signaling events; their removal would affect both primary oxidative damage and redox-based cellular transcriptional activity (Li et al., 2007). Therefore, cationic porphyrin-based antioxidants influence both inflammatory and immune pathways and also modulate secondary oxidative stress processes and could be thus more precisely viewed or described as cellular redox modulators.

In summary, the present data illustrate that elevated IOP augment NOS-2 expression, retinal protein nitration and apoptosis in rats. Thus, selective inhibition of NOS-2 and appropriate antioxidant therapy may prevent long-term visual loss and lead to improvement in the management of ocular hypertension.

Research Highlights

This is the first report showing the beneficial effect of a superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimetic, Mn(III) meso-tetrakis(N-n-hexylpyridinium-2-yl) porphyrin (MnTnHex-2-PyP5+) treatment in a rat model of elevated intraocular pressure (EIOP).

This is the first report showing that the lipophilic cationic Mn porphyrin, MnTnHex-2-PyP5+ can go through the eye and be detected in both the vitreous and retina via LC-ESI-MS/MS measurements.

This is the first report showing that preferential inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase (NOS-2) in rats with increased IOP has beneficial effects similar to a SOD mimic in a rat model of EIOP. Thus, presented data indicate that the highly oxidizing species peroxynitrite (ONOO−) gets formed in vivo in the presence of increased IOP.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by NIH/NCI Duke Comprehensive Cancer Center Core Grant (5-P30-CA14236-29), Batinic-Haberle Ines general research funds and a grant from Akdeniz University Research Foundation. (No.: 2007.01.0103.018).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akpinar D, Yargicoglu P, Derin N, Aslan M, Agar A. Effect of aminoguanidine on visual evoked potentials (VEPs), antioxidant status and lipid peroxidation in rats exposed to chronic restraint stress. Brain Res. 2007;1186:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslan M, Cort A, Yucel I. Oxidative and nitrative stress markers in glaucoma. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008;45:367–376. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslan M, Ryan TM, Townes TM, Coward L, Kirk MC, Barnes S, Alexander CB, Rosenfeld SS, Freeman BA. Nitric oxide-dependent generation of reactive species in sickle cell disease. Actin tyrosine induces defective cytoskeletal polymerization. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:4194–4204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208916200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslan M, Yücel I, Akar Y, Yücel G, Ciftçiog˘lu MA, Sanlioglu S. Nitrotyrosine formation and apoptosis in rat models of ocular injury. Free Radic Res. 2006;40:147–153. doi: 10.1080/10715760500456219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslan M, Yucel I, Ciftcioglu A, Savas B, Akar Y, Yucel G, Sanlioglu S. Corneal protein nitration in experimental uveitis. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2007;232:1308–1313. doi: 10.3181/0702-RM-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batinić-Haberle I, Rebouças JS, Spasojević I. Superoxide dismutase mimics: chemistry, pharmacology, and therapeutic potential. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010;13:877–918. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batinic-Haberle I, Spasojevic I, Stevens RD, Hambright P, Fridovich I. Manganese(III) meso-tetrakis(ortho-N-alkylpyridyl)porphyrins: synthesis, characterization, and catalysis of O2– dismutation. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 2002:2689–2696. [Google Scholar]

- Bazan NG, Marcheselli VL, Cole-Edwards K. Brain response to injury and neurodegeneration: endogenous neuroprotective signaling. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2005;1053:137–147. doi: 10.1196/annals.1344.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cort A, Ozturk N, Akpinar D, Unal M, Yucel G, Ciftcioglu A, Yargicoglu P, Aslan M. Suppressive effect of astaxanthin on retinal injury induced by elevated intraocular pressure. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010;58:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Paz MA, Epstein DL. Effect of age on superoxide dismutase activity of human trabecular meshwork. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1996;37:1849–1853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derin N, Akpinar D, Yargicoglu P, Agar A, Aslan M. Effect of alpha-lipoic acid on visual evoked potentials in rats exposed to sulfite. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2009;31:34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fechtner RD, Weinreb RN. Mechanisms of optic nerve damage in primary open angle glaucoma. Surv. Ophthalmol. 1994;39:23–42. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(05)80042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira SM, Lerner SF, Brunzini R, Evelson PA, Llesuy SF. Oxidative stress markers in aqueous humor of glaucoma patients. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2004;137:62–69. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00788-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-Sueta G, Radi R. Chemical biology of peroxynitrite: kinetics, diffusion, and radicals. ACS Chem Biol. 2009;4:161–177. doi: 10.1021/cb800279q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaasterland D, Tanishima T, Kuwabara T. Axoplasmic flow during chronic experimental glaucoma. 1. Light and electron microscopic studies of the monkey optic nervehead during development of glaucomatous cupping. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1978;17:838–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gherghel D, Griffiths HR, Hilton EJ, Cunliffe IA, Hosking SL. Systemic reduction in glutathione levels occurs in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005;46:877–883. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottanka J, Johnson DH, Martus P, Lütjen-Drecoll E. Severity of optic nerve damage in eyes with POAG is correlated with changes in the trabecular meshwork. J. Glaucoma. 1997;6:123–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham SL, Klistorner A. Electrophysiology: a review of signal origins and applications to investigating glaucoma. Aust. NZ J. Ophthalmol. 1998;26:71–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1606.1998.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall A, Karplus PA, Poole LB. Typical 2-Cys peroxiredoxins - structures, mechanisms and functions. FEBS J. 2009;276:2469–2477. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06985.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka MT, Loschmann PA, Gleichmann M, Weller M, Schulz JB, Wullner U, Klockgether T. Induction of nitric oxide synthase and nitric oxide-mediated apoptosis in neuronal PC12 cells after stimulation with tumor necrosis factoralpha/lipopolysaccharide. J. Neurochem. 1998;71:88–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71010088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herr DW, King D, Barone S, Jr., Crofton KM. Alterations in flash evoked potentials (FEPs) in rats produced by 3,30-iminodipropionitrile (IDPN) Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 1995;17:645–656. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(95)02007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe JW, Mitchell KW. Visual evoked potential changes in chronic glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Trans. Ophthalmol. Soc. UK. 1986;105(Pt 4):457–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Van Eldik LJ. S100 beta induces apoptotic cell death in cultured astrocytes via a nitric oxide-dependent pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1996;1313:239–245. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(96)00095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ischiropoulos H, Gow A. Pathophysiological functions of nitric oxide-mediated protein modifications. Toxicology. 2005;208:299–303. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzotti A. DNA damage and alterations of gene expression in chronicdegenerative diseases. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2003;50:145–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzotti A, Sacca SC, Cartiglia C, De Flora S. Oxidative deoxyribonucleic acid damage in the eyes of glaucoma patients. Am. J. Med. 2003;114:638–646. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L, Cepurna WO, Johnson EC, Morrison JC. Effect of general anesthetics on IOP in rats with experimental aqueous outflow obstruction. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000;41:3415–3419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YM, Bombeck CA, Billiar TR. Nitric oxide as a bifunctional regulator of apoptosis. Circ. Res. 1999;84:253–256. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kos I, Rebouc-as JS, De Freitas-Silva G, Salvemini D, Vujaskovic Z, Dewhirst MW, Spasojevic I, Batinic-Haberle I. The effect of lipophilicity of porphyrin-based antioxidants. Comparison of ortho and meta isomers of Mn(III) N-alkylpyridylporphyrins. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2009;47:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman DM, Harrison JM. Flash visual evoked potentials in the hypomyelinated mutant mouse shiverer. Doc. Ophthalmol. 2002;104:83–95. doi: 10.1023/a:1014415313818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Sonveaux P, Rabbani ZN, Liu S, Yan B, Huang Q, Vujaskovic Z, Dewhirst MW, Li CY. Regulation of HIF-1alpha stability through S-nitrosylation. Mol. Cell. 2007;26:63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Neufeld AH. Expression of nitric oxide synthase-2 (NOS-2) in reactive astrocytes of the human glaucomatous optic nerve head. Glia. 2000;30:178–186. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(200004)30:2<178::aid-glia7>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto N, Izumi H, Miyamoto R, Kubota T, Tawara A, Sasaguri Y, Kohno K. Nipradilol and timolol induce Foxo3a and peroxiredoxin 2 expression and protect trabecular meshwork cells from oxidative stress. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2009;50:2777–2784. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld AH, Sawada A, Becker B. Inhibition of nitric-oxide synthase 2 by aminoguanidine provides neuroprotection of retinal ganglion cells in a rat model of chronic glaucoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:9944–9948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieminen T, Lehtimäki T, Mäenpää J, Ropo A, Uusitalo H, Kähönen M. Ophthalmic timolol: plasma concentration and systemic cardiopulmonary effects. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 2007;67:237–245. doi: 10.1080/00365510601034736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okado-Matsumoto A, Batinic-Haberle I, Fridovich I. Complementation of SOD-deficient Escherichia coli by manganese porphyrin mimics of superoxide dismutase activity. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004;37:401–410. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley HA, Addicks EM. Chronic experimental glaucoma in primates. II. Effect of extended intraocular pressure elevation on optic nerve head and axonal transport. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1980;19:137–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saccà SC, Izzotti A, Rossi P, Traverso C. Glaucomatous outflow pathway and oxidative stress. Exp. Eye Res. 2007;84:389–399. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saccà SC, Pascotto A, Camicione P, Capris P, Izzotti A. Oxidative DNA damage in the human trabecular meshwork: clinical correlation in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2005;123:458–463. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.4.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarih M, Souvannavong V, Adam A. Nitric oxide synthase induces macrophage death by apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993;191:503–508. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada A, Neufeld AH. Confirmation of the rat model of chronic, moderately elevated intraocular pressure. Exp. Eye Res. 1999;69:525–531. doi: 10.1006/exer.1999.0732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder CE, Tenke CE, Givre SJ, Arezzo JC, Vaughan HG., Jr Striate cortical contribution to the surface-recorded pattern-reversal VEP in the alert monkey. Vision Res. 1991;31:1143–1157. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(91)90040-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shareef S, Sawada A, Neufeld AH. Isoforms of nitric oxide synthase in the optic nerves of rat eyes with chronic moderately elevated intraocular pressure. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1999;40:2884–2891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shareef SR, Garcia-Valenzuela E, Salierno A, Walsh J, Sharma SC. Chronic ocular hypertension following episcleral venous occlusion in rats. Exp. Eye Res. 1995;61:379–382. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(05)80131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng H, Tse HM, Jung JY, Zhang Z, Spasojevic I, Piganelli J, Batinic-Haberle I, Warner DS. Neuroprotective Efficacy From Parenteral Administration Of A Redox-Modulating lipophilic MnPorphyrin, MnTHex-2-PyP5+ J Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2010 doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.176701. under revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver S, Sohmer H, Kapitulnik J. Visual evoked potential abnormalities in jaundiced Gunn rats treated with sulfadimethoxine. Pediatr. Res. 1995;38:258–261. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199508000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spasojevic I, Kos I, Benov LT, Rajic Z, Fels D, Dedeugd C, Ye X, Vujaskovic Z, Reboucas JS, Leong KW, Dewhirst MW, Batinic-Haberle I. Bioavailability of metalloporphyrin-based SOD mimics is greatly influenced by a single charge residing on a Mn site. Free Radic Res. 2011;45:188–200. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2010.522575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tezel G. Oxidative stress in glaucomatous neurodegeneration: mechanisms and consequences. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2006;25:490–513. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tezel G, Yang X. Caspase-independent component of retinal ganglion cell death. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004;45:4049–4059. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tezel G, Yang X, Cai J. Proteomic identification of oxidatively modified retinal proteins in a chronic pressure-induced rat model of glaucoma. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005;46:3177–3187. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towle VL, Moskowitz A, Sokol S, Schwartz B. The visual evoked potential in glaucoma and ocular hypertension: effects of check size, field size, and stimulation rate. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1983;24:175–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse HM, Milton MJ, Piganelli JD. Mechanistic analysis of the immunomodulatory effects of a catalytic antioxidant on antigen-presenting cells: implication for their use in targeting oxidation-reduction reactions in innate immunity. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004;36:233–247. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yücel I, Yücel G, Akar Y, Demir N, Gürbüz N, Aslan M. Transmission electron microscopy and autofluorescence findings in the cornea of diabetic rats treated with aminoguanidine. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2006;41:60–66. doi: 10.1016/s0008-4182(06)80068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Li Y, Yue BY. Oxidative stress affects cytoskeletal structure and cell-matrix interactions in cells from an ocular tissue: the trabecular meshwork. J. Cell Physiol. 1999;180:182–189. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199908)180:2<182::AID-JCP6>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]