Abstract

We tested group interventions for women with a Turkish migration background living in Austria and suffering from recurrent depression. N = 66 participants were randomized to: (1) Self-Help Groups (SHG), (2) Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) Groups, and (3) a Wait-List (WL) Control condition. Neither SHG nor CBT were superior to WL. On an individual basis, about one third of the participants showed significant improvements with respect to symptoms of depression. Younger women, women with a longer duration of stay in Austria and those who had encountered a higher number of traumatic experiences, showed increased improvement of depressive symptoms. The results suggest that individual treatment by ethnic, female psychotherapists should be preferred to group interventions.

Keywords: Self-Help Group, group therapy, acculturation, migration, depression

Due to an increased demand for labor in Central Europe during the sixties and seventies of the 20th century workers’ recruitment agreements were signed by many European countries with Turkey. Today people from Turkey form the most numerous group of migrants in continental Europe. For example, in Austria, a country with a population of approximately eight million inhabitants, there are over 183,000 people with a Turkish migration background (Austrian Integration Fund, 2010).

These migrants experience the process of acculturation, which has been implicated in their mental health. Acculturation brings about cultural and psychological changes: these changes take place as a result of contact between cultural groups and their individual members. Because these cultural and psychological changes take place in both groups in contact, no individual or cultural group remains unchanged following culture contact; acculturation is a two-way interaction, resulting in actions and reactions to the contact situation. In many cases, most change takes place in non-dominant immigrant or ethnocultural communities. However, all societies of settlement (particularly their metropolitan cities) have experienced massive transformations following years of receiving migrants, often producing xenophobic reactions. These changes can be minor or substantial, and range from being easily accomplished through to being a source of major cultural and psychological disruption (Berry, 1997).

Adaptation to living in culture-contact settings takes place over time. Occasionally it is stressful, but often it results in some form of mutual accommodation between the groups and individuals (Berry, 2007). At the psychological level, it is important to note that not every individual enters into, and participates in, or changes in the same way; there are vast individual differences in psychological acculturation, even among individuals who live in the same acculturative arena (Sam & Berry, 2006). These changes can be a set of rather easily accomplished behavioral shifts (e.g., in ways of speaking, dressing, and eating) or they can be more problematic, producing acculturative stress (Berry, 2006) usually manifested by uncertainty, anxiety, and depression.

Adaptations to the experience of acculturation can be primarily internal or psychological (e.g., sense of well-being, or self-esteem) or sociocultural (Ward, 1996), linking the individual to others in the new society as manifested for example in competence in the activities of daily intercultural living.

As noted above, individuals vary in how they deal with acculturation. The concept of acculturation strategies refers to the various ways that groups and individuals seek to acculturate. Four acculturation strategies have been derived from two basic issues facing all acculturating peoples. These issues are based on the distinction between orientations towards one’s own group, and those towards other groups (Berry, 1997). This distinction is rendered as (i) a relative preference for maintaining one’s heritage culture and identity and (ii) a relative preference for having contact with and participating in the larger society along with other ethnocultural groups.

The orientations of immigrants and ethnocultural groups to these two issues intersect to define four acculturation strategies. When individuals do not wish to maintain their cultural identity and seek daily interaction with other cultures, the Assimilation strategy is defined. In contrast, when individuals place a value on holding on to their original culture, and at the same time wish to avoid interaction with others, then the Separation alternative is defined. When there is an interest in both maintaining ones original culture, while in daily interactions with other groups, Integration is the strategy. In this case, there is some degree of cultural integrity maintained, while at the same time seeking, as a member of an ethnocultural group, to participate as an integral part of the larger social network. Finally, when there is little possibility or interest in cultural maintenance (often for reasons of enforced cultural loss), and little interest in having relations with others (often for reasons of exclusion or discrimination) then Marginalization is defined. Note that integration has a very specific meaning within this framework: it is clearly different from assimilation (because there is substantial cultural maintenance with integration), and it is not a generic term referring to any kind of long term presence, or involvement, of an immigrant group in a society of settlement (Berry, 2007).

In the case of migrants from Turkey, they are often unskilled laborers who face dire working and living conditions as well as xenophobic attitudes in Austria. Most of them usually affiliate with their compatriots almost exclusively and avoid socializing with native born Austrians (Friesl, Polak, & Hamachers-Zuba, 2009; Sahin, 2006). Thus, in the sense of Berry (1997), they are choosing Separation rather than Integration as an acculturation strategy, thereby increasing acculturative stress (Berry, 1997; 2006). By idealizing their home country, old customs from childhood are still adhered to and homesickness is a frequent phenomenon among them. Many Turkish migrants also usually foster the idea of eventually re-migrating to Turkey, although these plans are rarely realized (Sahin, 2006). According to official sources, first and second generation migrants are still disadvantaged with respect to schooling and vocational training and with regard to their high unemployment rates and poor economic situation as compared to native born Austrians (Austrian Integration Fund, 2010; for details see also Renner & Sladky, 2010).

Turkish migrants tend to perceive Central European society as too permissive with respect to child rearing; hence the interaction of cultures is avoided. Children are brought up in Turkish, being educated according to strictly conservative Islamic conceptions and regulations and girls are expected to be married to men of Turkish descent, with marriages often being arranged by their parents (Akpinar, 2003; Erim, 2009).

As far as women are concerned, migration has hardly ever led to increased autonomy and independence. According to traditional gender roles, anything that could be perceived as “westernized” is anxiously avoided. Turkish women in Austria usually get married at an average age of 22.3 years, whereas Austrian women get married at an average age of 29.5 years. On average they give birth to 2.41 children as compared to Austrian women who have an average of 1.27 children (Austrian Integration Fund, 2010). Most Turkish women in Austria had to leave behind their social networks in Turkey. They have virtually no knowledge of German and thus remain in isolation. For the first couple of years after getting married, they usually have to live at their parents-in-law’s homes, helping in the household and being denied basic rights like socializing with their friends or having money of their own (Renner & Sladky, 2010). When older, and after having given birth to a number of children, women gradually achieve an improved societal status, implying a higher degree of respect also from their male compatriots (Sahin, 2006).

On the basis of these difficult living conditions and their limited involvement with Austrian society, there is a high incidence of psychological and psychosomatic illness among Turkish migrant women in Central Europe. Bhugra (2003) and Lindert, von Ehrenstein, Priebe, Mielck, and Brähler (2009), in their recent meta-analysis have pointed to an increased risk of anxiety and depression in voluntary migrants in general. Erim (2009) and Kleinemeier, Yagdiran, Censi, and Haasen (2004) have explained in detail how the traditional values of Turkish extended families conflict with Central European ones and how social isolation, especially in women contributes to acculturative stress, with clinical symptoms of depression and psychosomatic illness resulting. For example, Cicek (1990) reported a lifetime risk of depression of 81% for Turkish migrant women as opposed to 45% for Turkish migrant men. According to the same study, 71% of the women and 55% of the men currently complained about psychosomatic symptoms. Whereas for religious reasons the overall suicide rates among female Turkish migrants are lower than among Central European natives, among younger Turkish women living in Germany a suicide risk is 1.8 times higher as compared to German women and an increased risk of attempted suicide have been reported (Löhr, Schmidtke, Wohner, & Sell, 2006; Razum & Zeeb, 2004).

Bäärnhilm and Ekblad (2000) and Kleinemeier et al. (2004) reported that Turkish migrants tended to distrust western medical illness concepts, explanations, and remedies – especially psychiatric interventions - and frequently resorted to traditional healers. Erim (2009) has pointed out that western medical interventions have to take into account both culturally specific symptoms and illness concepts as well as differences between cultures in the course of therapeutic relationships. Additional problems may result from the use of interpreters (Westermeyer, 1990).

From these considerations we developed the idea of culturally sensitive, community based guided self-help interventions for Turkish migrant women with recurrent depression. The self-help groups were meant to promote the participants’ autonomy, empowerment, and problem solving potential and thereby should help them cope with clinical symptoms of depression and somatization. Self-help groups, as a culturally congruent intervention for Turkish migrants have also been suggested for example by Erim (2009). Lay counseling has been implemented successfully towards assisting refugees and Internally Displaced Persons in Cambodia and North Africa by the “Transcultural Psychosocial Organization” (TPO) (Eisenbruch, de Jong, and van de Put, 2004) and by the “Service for the Treatment and Rehabilitation of Torture and Trauma Survivors” (STARTTS) in Australia (Aroche & Coello, 2004). Similarly, self-help activities have been instrumental towards promoting the acculturation of Yugoslav migrants in Switzerland (Perren-Klingler, 2001). In previous research of our own we had successfully employed guided self-help groups for male and for female asylum seekers and refugees from Chechnya which markedly reduced depressive and post-traumatic symptoms, the effect being on a par with a Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) Control Group (Renner, 2008; Renner, Bänninger-Huber, & Peltzer, accepted).

Accordingly, in the present study we had devised guided Self-Help Groups (SHG) for female Turkish migrants as a means of reducing depression and general symptomatology. In a randomized controlled study, we intended to compare the effects of these interventions with a Wait-List (WL) Control Group and with CBT on a group basis. We chose the latter approach for comparative reasons, as CBT in a group as well as in a single setting is well established as a method towards treating mild to moderate depression in psychiatric outpatients (Feldman, 2007; de Jong-Meyer, Hautzinger, Kühner, & Schramm, 2007; for group CBT cf., Miranda et al., 2006; Misri, Reebye, Corral, & Mills, 2004).

We therefore hypothesized that Guided Self-Help Groups for female Turkish migrants would be significantly superior to a Wait-List Control Group and would be equally effective as Group CBT in decreasing (1) depressive and (2) somatic symptoms, as well as (3) general psychopathology in Turkish migrant women with recurrent depression (ICD-10 F33). Treatment effects were expected to remain stable at a one-month and a six-months follow-up occasion. In addition to a quantitative approach towards testing these hypotheses, we intended to employ qualitative methods in order to assess the working mechanisms of the interventions.

METHOD

Participants

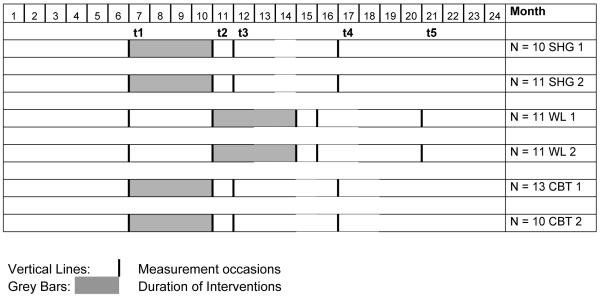

A total of N = 66 female Turkish migrants in Austria participated. Sixty-two of them were migrants of the first generation and four of the second generation. Their mean age was 42.7 years (s = 8.7, range 28 to 61 years). On average, they had 5.9 years of schooling (s = 3.1, range, 0 to 13) and their average duration of stay in Austria was 18.6 years (s = 8.2, range 1 to 34 years). Twenty-one of them were randomized to the Self-Help Group (SHG) condition, 23 to the CBT and 22 to the Wait-List (WL) Control condition. Out of this sample, at t2 (when SHG and CBT had been finished), N = 38 participants (15 in SH, 11 in CBT, and 12 in WL) still were present and thus could be included in the analysis of outcome. At t1 (pre-treatment), according to Kruskal-Wallis tests, the three groups did not differ on the various measures employed (for measurement occasions see Figure 1, which also shows the time plan as originally scheduled).

Figure 1.

Initial Time Plan with Initial Group Sizes, Duration of Interventions, and Measurement Occasions

Participants had been recruited at local Turkish clubs, at a Mosque, and with the help of medical experts. Before being accepted for the study, in addition, all the participants underwent psychiatric screening, according to which there was no acute risk of suicide and all of the participants met the Diagnostic Criteria of Recurrent Depression (F 33) according to ICD-10. Whereas initially, approximately N = 130 women had indicated that they wished to participate, many dropped out soon because of having lost interest, because their husband had objected, or because they had not met psychiatric criteria for participation. Moreover, after initial enthusiasm on the part of the Turkish community, recruitment of additional participants became increasingly difficult. Therefore, the idealized timetable as shown in Table 1 had to abandoned and the second SHG, the second CBT, and the second WL control interventions had to take place considerable later than originally scheduled (for details of the procedure see Renner, 2010).

Table 1.

The Effects of SHG and CBT as Compared to Wait List (t1 vs. t2)

| SHG t1 | SHG t2 | CBT t1 | CBT t2 | WL t1 | WL t2 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 15 | Wilco- xon |

N = 11 | Wilco- xon |

N = 12 | Wilco- xon |

||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | p | M | SD | M | SD | p | M | SD | M | SD | p | |

| CESD | 1.74 | 0.62 | 1.53 | 0.58 | .125 | 1.69 | 0.6 | 1.39 | 0.46 | .247 | 1.69 | 0.52 | 1.7 | 0.56 | .638 |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| BSI | |||||||||||||||

| 1 Somatization | 2.03 | 1.06 | 1.88 | 0.88 | .550 | 1.83 | 1.13 | 1.66 | 0.77 | .838 | 1.88 | 0.98 | 2.06 | 1.11 | .444 |

| 2 Obsessive-Comp. | 2.15 | 0.97 | 2.24 | 0.89 | .449 | 2.06 | 1.03 | 1.98 | 1.01 | .755 | 2.19 | 0.85 | 2.22 | 1.03 | .919 |

| 3 Interpers. Sens. | 2.13 | 0.91 | 2.07 | 0.96 | .637 | 1.64 | 1.09 | 1.64 | 0.81 | .720 | 2.22 | 1.2 | 2.48 | 1.36 | .306 |

| 4 Depression | 2.18 | 0.9 | 2.24 | 1.08 | .706 | 2.24 | 1.2 | 1.67 | 1.03 | .007 | 2.04 | 1.03 | 2.36 | 1.19 | .130 |

| 5 Anxiety | 2.3 | 0.76 | 2.14 | 1.04 | .309 | 2.14 | 1.25 | 1.68 | 0.93 | .074 | 1.93 | 0.88 | 2.19 | 1.37 | .449 |

| 6 Hostility | 1.97 | 0.71 | 1.65 | 0.84 | .138 | 1.25 | 1.19 | 1.05 | 0.73 | .681 | 1.95 | 1.28 | 1.97 | 1.1 | .894 |

| 7 Phobic Anxiety | 1.57 | 1.1 | 1.75 | 0.96 | .582 | 1.53 | 1.38 | 1.24 | 1.03 | .332 | 1.15 | 0.7 | 1.76 | 1.28 | .055 |

| 8 Paranoid Ideation | 1.84 | 0.78 | 1.95 | 0.91 | .849 | 1.73 | 0.95 | 1.62 | 0.88 | .607 | 2.08 | 1.17 | 2.13 | 1.53 | .969 |

| 9 Psychoticism | 1.53 | 0.83 | 1.64 | 0.95 | .469 | 1.29 | 1.17 | 1.19 | 1.12 | .608 | 1.42 | 0.85 | 1.73 | 1.35 | .212 |

| GSI | 1.97 | 0.7 | 1.95 | 0.78 | .910 | 1.77 | 1 | 1.53 | 0.8 | .213 | 1.88 | 0.78 | 2.09 | 1.07 | .209 |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| BL | 1.73 | 0.53 | 1.89 | 0.51 | .334 | 1.56 | 0.68 | 1.58 | 0.52 | .959 | 1.71 | 0.66 | 1.74 | 0.55 | 1.000 |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| HTQ | 2.36 | 0.63 | 2.36 | 0.59 | .925 | 2.24 | 0.71 | 2.19 | 0.62 | .531 | 2.45 | 0.7 | 2.55 | 0.87 | .638 |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| PHQ | |||||||||||||||

| 1 Somatic | 0.84 | 0.45 | 0.97 | 0.4 | .220 | 1 | 0.47 | 0.87 | 0.28 | .220 | 0.91 | 0.42 | 1.01 | 0.39 | .168 |

| 2 Depression | 1.51 | 0.68 | 1.56 | 0.62 | .253 | 1.51 | 0.9 | 1.42 | 0.8 | .721 | 1.5 | 0.84 | 1.56 | 0.89 | .814 |

| 4 Overall | |||||||||||||||

| Impairment | 2 | 0.85 | 1.27 | 0.88 | .054 | 1.45 | 1.04 | 1.09 | 1.14 | .157 | 1.92 | 1.08 | 1.64 | 1.36 | .680 |

Interventions

From original time plan as shown in Figure 1, it can be seen that SHG and CBT, as well as the time delayed SHG for the WL Control Group were administered in two sub groups in order to attain an approximate initial group size of ten participants. All three types of interventions comprised 15 group sessions of 90 minutes’ duration and took place at Innsbruck University.

Self-Help Groups

The Self-Help Groups as well as the time-delayed Self-Help Groups in the WL conditions were guided by three medical students and one law student, respectively. All group leaders were female and of Turkish descent, being in their twenties. During a preliminary phase of six months, the potential group leaders who had no previous experience in psycho-social work, participated in four workshops conducted by Vedat Sar, a guest expert and Professor of Psychiatry of Istanbul University, by Karl Peltzer, an international South Africa based expert on lay counseling and by local professors of Clinical and Developmental Psychology. In the course of the group meetings, the group leaders were supervised on a monthly basis. The group leaders were instructed to allow group participants to arrange their meetings according to their own wishes without a fixed schedule, adhering, however, to basic principles of group work, with special regard to confidentiality. Group leaders also had been instructed to design Self-Help interventions towards promoting independence, competencies, and self-healing power.

CBT Groups

Therapeutic sessions were scheduled according to a fixed structure adapted from treatment manuals in current use by behavior therapists in German speaking countries (Hautzinger, Stark, & Treiber, 2003; Herrle & Kühner, 1994). Group therapy was conducted by a female behavior therapist of Austrian descent, and assisted by a female interpreter.

Assessment

Measures

We measured symptoms of depression by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D with 20 items, Radloff, 1977) and general psychopathology by the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI, Derogatis, 1993), which comprises 53 items on nine scales (Somatization, Obsessive-Compulsive, Interpersonal Sensitivity, Depression, Anxiety, Hostility, Phobic Anxiety, Paranoid Ideation, and Psychoticism) plus the global index GSI. Somatic complaints were measured by 24 items of the List of Complaints (“Beschwerdeliste”) (Turkish version by Schwab & Tercanli, 1987), and symptoms of post-traumatic stress by items 1 to 16 from Part IV of the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ, Mollica et al., 1992). As an additional measure of clinical symptomatology, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ, Turkish version by Uzuner Özer, 2004) was employed (Part I, 13 items, somatic complaints; Part II, nine depressive symptoms, Part III, five questions pertaining to symptoms of anxiety1, and Party IV, estimating the overall degree of impairment by a four-point-scale). The number of traumatic events encountered, witnessed or heard about was assessed by the Life Events Checklist from the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) (Blake et al., 1990).

Scales for which no Turkish versions were available were translated and back translated into Turkish. Illiterate participants received individual help towards answering the questions. All measures were selected with respect to their well-known reliability and other psychometric properties, with special respect to being employed in a trans-cultural context (for details, cf., Renner, 2010)2.

Qualitative Methods

Qualitative results have been obtained from (1) the participants final reports at the end of the interventions, (2) from the groups leaders’ and therapists’ protocols and (3) from the group leaders’ supervision (in the case of SHG).

RESULTS

Because of the limited sample size, the basic assumptions of Analysis of Variance were not fulfilled, and thus we decided to test the hypotheses by non-parametric tests.

The Effects of SHG and CBT as Compared to WL

We assessed the effects of the SHG and the CBT-Group as compared to WL between t1 and t2. These results are shown in Table 1. It can be seen that both for the SHG and the WL, with respect to none of the measures a significant effect could be obtained between t1 and t2 and thus, SHG has been ineffective. CBT achieved a significant reduction of depressive symptoms as measured by Scale 4 of the BSI but on all the other scales, effects of CBT were not significant.

The Effects of the Wait-List Group

As we have shown in Table 1, the WL group received a time delayed intervention between t2 and t3. Out of twelve participants who were present in the WL group at t2, N = 8 participants still were present at t3 and thus were included in the analysis. In this case, depressive symptoms as measured by the CES-D were reduced significantly from 1.76 (s = 0.52) at t2 to 1.28 (s = 0.36) at t3 (Wilcoxon p = .012). On all the other scales, no significant changes were obtained3.

Follow-Up Measurements

As has been shown in Figure 1, SHG and CBT received a one-month follow up at t3 and a six-months follow up at t4, whereas the WL group received the respective follow-up measurements at t4 and t5. From the SHG, N = 14, from the CBT group, N = 10, and from the WL group, N = 7 participants took part in the final measurements and thus could be included in the analysis of possible changes following the interventions. According to Friedman-Tests, neither for the Self-Help nor for the WL groups, significant changes after the end of the interventions had occurred. For the CBT groups, however, there was a significant deterioration with respect to BSI Scale 4 (Depression: t2: M = 1.60, s = 1.06, t3: M = 1.77, s = 0.85, t4: M = 2.48, s = 1.20; Friedman p = .002), BSI Scale 6 (Hostility: t2: M = 0.98, s = 0.73, t3: M = 1.04, s = 1.01, t4: M = 1.78, s = 1.17; Friedman p = .015) and BSI Scale 8 (Paranoid Ideation: M = 1.44, s = 0.69, t3: M = 1.60, s = 0.79, t4: M = 1.98, s = 0.97; Friedman p = .046).

Responders and Non-Responders

On the basis of demographic variables, a linear regression analysis was employed in order to identify possible predictors of a positive outcome. As a dependent variable, the score on CES-D has been selected, as depressive symptomatology had been the primary target of the intervention. For this analysis, the data from all N = 34 participants who had completed an intervention either in the SHG, the WL-Group (with time delayed Self-Help), or in the CBT Group have been taken together. The results of the linear regression have been summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic Variables as Predictors of Change on the CES-D

| Non standardized coefficients |

Standardized coefficients |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| B | Standard error |

Beta | T | Sign. | |

| Constant | 2.43 | 0.86 | 2.83 | .009** | |

| Age | −0.05 | 0.02 | −0.87 | −3.19 | .004** |

| Duration of stay | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.47 | 2.24 | .034* |

| Generation of migration | −0.51 | 0.46 | −0.18 | −1.09 | .286 |

| Years of schooling | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.39 | −1.84 | .079 |

| number of children | −0.02 | 0.11 | −0.04 | −0.21 | .838 |

| CBT (dummy) | −0.05 | 0.22 | −0.05 | −0.24 | .814 |

| WL (dummy) | −0.02 | 0.21 | −0.02 | −0.08 | .935 |

| LEC: Traumatic Events Experienced |

0.09 | 0.03 | 0.64 | 3.14 | .004** |

| LEC: Traumatic Events Witnessed |

0.02 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.44 | .662 |

From Table 2 it can be seen that a younger age, a longer duration of stay in Austria, and a higher number of traumatic events as measured by the LEC were predictive of a higher amount of symptom reduction on the CES-D. In order to distinguish responders from non-responders on an individual basis, for each of the N = 34 participants, the Reliable Change Index according to Jacobson, Follette, & Revenstorf (1984) has been computed on the 5% level of significance. According to this statistic, N = 12 (35.3%) participants had improved significantly, N = 1 (2.9%) had deteriorated significantly, whereas there was not significant change in the remaining N = 21 (61.8%) participants.

Qualitative Results

The issues most frequently discussed in the course of group sessions were family affairs and difficulties pertaining to husbands and children, including the participants’ wishes to change their living conditions and to increase social networks of their own. As their main concerns, many women expressed feeling lonely and being unable to deal with excessive demands in dealing with family and household affairs. In both, Self-Help and CBT groups, many participants indicated to be disappointed about not being offered what they referred to as “real therapy”, i.e., an intervention by an obviously competent, senior therapist in a single setting. Moreover, many group members expressed their concerns about confidentiality.

Whereas symptom reduction could be achieved only in some cases, the participants had experienced their meetings in a very satisfactory way and reported that, in the course of group sessions, they had experienced an increased amount of mutual trust, that they had acquired problem solving strategies and regained their strength. As opposed to the CBT condition, members of the SHG expressed their desire to continue contact on an informal basis. When group leaders wished to act on this idea and suggested detailed steps towards continuing group meetings on an informal basis, however, participants turned out to be unable to continue their meetings without their group leaders’ help.

DISCUSSION

Guided Self-Help-Groups have not been superior to Wait-List in reducing clinical symptoms in female Turkish migrants and similarly, CBT Group interventions were of no avail. Although the CBT interventions had a significant effect on one of the scales it should be kept in mind that in the course of follow-up measurements, CBT, as opposed to SHG and WL, even was accompanied by significant deterioration after the interventions had been finished. Analyses of single cases have revealed that about one third of the participants had achieved a significant decrease of depressive symptoms. Whereas a substantial number of participants had dropped out prematurely, qualitative assessments of those who completed the study pointed to subjective benefits with respect of regaining strength, feeling supported by the group, and sharing experiences.

Similarly, in a recent attempt to reduce clinical symptoms, Lampe and Barbist (2010) have employed psychodrama on a group basis, and also obtained negative results in Turkish migrant women in Austria. Sleptsova, Wössmer, and Langewitz (2009) did not achieve symptom reduction in Turkish and Kurdish migrants with chronic pain in Switzerland and Calliess, Schmid-Ott, Akguel, Jäger, & Ziegenbein (2007) pointed to overall skeptical attitudes towards psychotherapy as expressed by Turkish migrants in Germany.

On the other hand, however, a German psychotherapist of Turkish descent (Erim, 2009), reported that her group interventions were at least partly successful in reducing pain in Turkish migrant women. Similarly, when applied to Turkish patients in their home country, CBT and psychodrama on a group basis had been effective in reducing depression (Hamamci, 2006) and instigating weight-loss in obese patients (Sertöz & Mete, 2005). Eye-Movement-Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) was effective in reducing post-traumatic symptoms (Konuk et al., 2006) and other methods towards reducing post-traumatic stress have been employed successfully to Turkish patients in their home country by Bahar et al. (2008). In the light of these comparative findings, western therapeutic methods could be expected to be effective with Turkish patients, no less than with Central European ones and the negative outcome of the present study as well as the high number of drop-outs should be explained by the limitations and possible shortcomings of our procedure:

Firstly, the leaders of the Self-Help Groups, though of Turkish descent, were young female students of Innsbruck University and many group members, being considerably older than their group leaders, may have perceived them as too westernized and as too young to be taken seriously. Moreover, passive female gender roles of Turkish culture may not be compatible with the self-help concept which also conflicts with a conservative Turkish understanding of healing. According to Wössmer and Sleptsova (2006), Turkish patients in Switzerland frequently expected the therapist to take on an authoritative role on a higher level of hierarchy. This explanation, pertaining to traditional gender and professional roles of Turkish society is supported by our finding that younger group members with a comparatively longer duration of stay i.e., those, who can be expected to be less identified with traditional Turkish gender roles, tended to report increased benefits of the interventions on their questionnaires.

The additional result, suggesting an increased benefit for women who had experienced a higher number of traumatic life events, is in line with previous results obtained from lay interventions for refugees and asylum seekers (Renner et al., accepted; Renner, 2010). Still this finding should be interpreted with caution, as younger women and those with a longer duration of stay, i.e., those with a higher degree of acculturation to Austrian society, may have been less reluctant to report traumatic events than those who are less acculturated.

It should also be pointed out that group therapy only offers a limited degree of confidentiality, a fact, which was frequently addressed by the participants. In Turkish communities in Austria most of their members can be expected to know each other personally and this may have kept many group members from expressing their thoughts and feelings openly. Another crucial point has been addressed by Sar (2010), who suspected that a considerable number of participants might be suffering from symptoms of dissociation which may have added to clinical symptomatology and could not be addressed adequately by the methods employed.

Moreover, group therapy may increase effects of so-called “negative social support”, such as for example hostility, derogation, or not being taken seriously by the other group members (Laireiter, Fuchs, & Pichler, 2007). Adelman (1988), with special respect to groups intended to promote psychological adjustment in migrants, pointed to a “contagion effect” of exacerbating emotions, similar to “co-rumination” in the sense of “extensively discussing and re-visiting problems” (Rose, 2002, p. 1830) in groups of young people. Co-rumination leads to increased levels of anxiety and depression while enhancing perceived friendship quality (Calmes and Roberts, 2008; Rose, Carlson, & Waller, 2007). This finding corresponds with the present qualitative results which point to satisfactory group climate and positive experiences of sharing and communicating, while on an objective level, symptom reduction has not been achieved. Similarly, Battegay (1997) pointed to the group participants’ increased willingness to accept their living conditions as an effect of social support experienced by group participation. Overall, these results confirm Cutrona and Russell’s (1990) model, according to which, in the light of unchangeable living conditions, social support can be expected to yield emotional rather than instrumental effects.

The latter aspects of uncontrollable living conditions may also contribute to a passive role on the part of group participants whose clinical symptoms can be interpreted as their last resource in an otherwise hopeless struggle. In this sense, clinical symptoms may be instrumental in attracting the family’s attention, reducing hostility and, at least to some extent, consequently be relieved of some duties (Erim, 2009; Sar, 2010). Thus, from a standpoint of learning theory, clinical symptoms may be reinforced and maintained secondarily, making them resistant to change.

Towards developing effective interventions for Turkish migrant women, from the present results, the following recommendations can be derived:

In the light of Separation as the acculturation strategy employed most frequently by Turkish migrants, interventions should be culturally congruent, meeting the participants’ illness concepts and expectations as closely as possible, especially taking into account the needs of older women and of those who just recently have arrived in the host country;

In order to achieve this goal, wherever possible, therapists should have a Turkish migration background and women should work with women and men with men, according to traditional gender roles; in addition, according to conservative Turkish preconceptions, young female therapists may not be taken seriously by some of the older participants;

Also as a consequence of Turkish migrants’ Separation, self-help groups should not be expected to be accepted, as their theoretical basis is a typically “western” one, which does not agree with traditional Turkish preconceptions of being “healed” by a person of hierarchy;

Along these lines, at least initially, therapists should present themselves as competent experts rather than as facilitators of individual problem solving capacities;

In order to discharge patients from current pressures in their everyday life, at least initially in-patient treatment may be preferable to an out-patient setting;

Treatment should try to improve the patient’s psycho-social situation and should thus be designed towards taking a longer period of time.

Future studies might take into account age, length of stay, employment and marital status as well as other socio-demographic variables which might moderate the outcome of interventions for Turkish migrant women with depression.

In addition to culturally sensitive treatment on an individual basis, living conditions of Turkish women in Austria should not be considered as unchangeable on a societal level. Both, extremely conservative gender roles within many women’s families and xenophobic attitudes among some native born Austrians may contribute to the dire living conditions of Turkish migrant women and every effort should be made to bring about change in this respect. On the family level, systemic therapy, carried out by female therapists of Turkish descent might be worth experimenting with.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the funding of the present study by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) (Reference Number P20523-G14). The present study was initiated by Walter Renner at the University of Innsbruck and has been continued during his time as an Associate Professor at Private University UMIT (Hall, Austria).

Footnotes

In order to save space, results of PHQ, Part IV will not be reported here. They are available upon request.

We are indebted to an anonymous reviewer for suggesting to us some of the questionnaires employed.

Detailed results are available upon request.

Contributor Information

Walter Renner, University of Innsbruck and Private University of Health Sciences, Medical Informatics and Technology (UMIT) at Hall (Austria).

John W. Berry, Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada.

REFERENCES

- Adelman MB. Cross-cultural adjustment. A theoretical perspective on social support. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 1988;12:183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Akpinar A. The honour/shame complex revisited: Violence against women in the migration context. Women’s Studies International Forum. 2003;26:425–442. [Google Scholar]

- Aroche J, Coello MJ. Ethnocultural considerations in the treatment of refugees and asylum seekers. In: Wilson JP, Drozdek B, editors. Broken Spirits. Brunner-Routledge; New York: 2004. pp. 53–80. [Google Scholar]

- Austrian Integration Fund (Österreichischer Integrationsfonds), editor. Migration & Integration. Zahlen.Daten.Fakten [Migration and integration. Statistical data and facts] Austrian Integration Fund; Vienna (Austria): 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bäärnhilm S, Ekblad S. Turkish migrant women encountering health care in Stockholm: A qualitative study of somatization and illness meaning. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2000;24:431–452. doi: 10.1023/a:1005671732703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahar Z, Öztürk M, Beser A, Eker G, Cakaloz B, Bahar Z. Evaluation of interventions based on depression sign scores of adolescents. Social Behavior and Personality. 2008;36:123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Battegay R. Group psychotherapy with immigrants from Turkey. Group Analysis. 1997;30:217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 1997;46:5–68. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Acculturative stress. In: Wong P, Wong L, editors. Handbook of multicultural perspectives on stress and coping. Springer; New York: 2006. pp. 126–141. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Acculturation and identity. In: Bhugra D, Bhui K, editors. Textbook of cultural psychiatry. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2007. pp. 169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Bhugra D. Migration and depression. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2003;108(Suppl. 418):67–72. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.108.s418.14.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LN, Kaloupek DG, Klauminzer G, Charney DS, Keane TM. A clinician rating scale for assessing current and lifetime PTSD: The CAPS-1. Behavior Therapist. 1990;18:187–188. [Google Scholar]

- Calliess IT, Schmid-Ott G, Akgül G, Jäger B, Ziegenbein M. Einstellung zu Psychotherapie bei jungen türkischen Migranten in Deutschland [Attitudes towards psychotherapy of young second-generation Turkish immigrants living in Germany. Psychiatrische Praxis. 2007;34:343–348. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-986191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calmes CA, Roberts JE. Rumination in interpersonal relationships: Does co-rumination explain gender differences in emotional distress and relationship satisfaction among college students? Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2008;32:577–590. [Google Scholar]

- Cicek H. Psychosexuelle Probleme von ausländischen Patienten [Psychosexual problems encountered by patients from abroad] Psychomed. 1990;2:244–246. [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Russell DW. Type of social support and specific stress: Toward a theory of optimal matching. In: Saronson IG, Saronson BR, Pierce GR, editors. Social Support: An Interactional View. Wiley; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong-Meyer R, Hautzinger M, Kühner C, Schramm E. Evidenzbasierte Leitlinie zur Psychotherapie Affektiver Störungen [Evidence based guidelines for psychotherapy of affective disorders] Hogrefe; Göttingen: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (administration, scoring, and procedures manual. third edition Minneapolis: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbruch M, de Jong JTVM, van de Put W. Bringing order out of chaos: A culturally competent approach to managing the problems of refugees and victims of organized violence. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17:123–131. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000022618.65406.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erim Y, editor. Klinische interkulturelle Psychotherapie. Ein Lehr- und Praxisbuch [Clinical cross-cultural psychotherapy. A textbook] Kohlhammer; Stuttgart (Germany): 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman G. Cognitive and behavioral therapies for depression: Overview, new directions, and practical recommendations for dissemination. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2007;30:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesl C, Polak R, Hamachers-Zuba U, editors. Die ÖsterreicherInnen. Wertewandel 1990 – 2008 [Male and female Austrians. Changing values 1990 to 2008] Czernin; Vienna (Austria): 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hamamci Z. Integrating psychodrama and cognitive behavioral therapy to treat moderate depression. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 2006;33:199–207. [Google Scholar]

- Hautzinger M, Stark W, Treiber R. Kognitive Verhaltenstherapie bei Depressionen [Cognitive-behavioral therapy of depression] Beltz; Weinheim (Germany): 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Herrle J, Kühner C, editors. Depression bewältigen. Ein kognitiv-verhaltenstherapeutisches Gruppenprogramm nach P. M. Lewinsohn [Managing depression. A cognitive-behavioral group program according to P. M. Lewinsohn] PVU; Weinheim (Germany): 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Follette WC, Revenstorf D. Toward a standard definition of clinically significant change. Behavior Therapy. 1984;15:309–311. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinemeier E, Yagdiran O, Censi B, Haasen C. Psychische Störungen bei türkischen Migranten. Inanspruchnahme einer Spezialambulanz [Psychiatric disorders in Turkish migrants. Utilzation of a special outpatient department] Psychoneuro. 2004;30:628–632. [Google Scholar]

- Konuk E, Knipe J, Eke I, Yuksek H, Yurtsever A, Ostep S. The effects of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy on posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of the 1999 Marmara, Turkey, earthquake. International Journal of Stress Management. 2006;13:291–308. [Google Scholar]

- Laireiter A-R, Fuchs M, Pichler M-E. Negative soziale Unterstützung bei der Bewältigung von Lebensbelastungen. [Negative social support in the adaptation to life stress.] Zeitschrift für Gesundheitspsychologie. 2007;15:43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lampe A, Barbist MT. An intercultural group in support of Turkish migrant women. In: Renner W, editor. Female Turkish migrants with recurrent depression. A research report on the effectiveness of group interventions: Theoretical assumptions, results, and recommendations. Studia; Innsbruck (Austria): 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lindert J, von Ehrenstein OS, Priebe S, Mielck A, Brähler E. Depression and anxiety in labor migrants and refugees – A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69:246–257. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löhr C, Schmidtke A, Wohner J, Sell R. Epidemiologie suizidalen Verhaltens von Migranten in Deutschland [Epidemiology of suicidal behavior among migrants in Germany] Suizidprohylaxe. 2006;33:171–175. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Green BL, Krupnick JL, Chung J, Siddique J, Belin T, Revicki D. One-year outcomes of a randomized clinical trial treating depression in low-income minority women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:99–111. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misri S, Reebye P, Corral M, Mills L. The use of paroxetine and cognitive-behavioral therapy in postpartum depression and anxiety: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:1236–1241. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollica RF, Caspi-Yavin Y, Bollini P, Truong T, Tor S, Lavelle J. The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire: Validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder in Indochinese refugees. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1992;180:111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perren-Klingler G. Trauma: Wissen, Können, Selbstaufbau. Hilfe zur Selbsthilfe bei Flüchtlingen [Trauma: knowledge, abilities, self-empowerment. Being taught to help oneself] In: Verwey M, editor. Trauma und Ressourcen [Trauma and resources] Verlag für Wissenschaft und Bildung; Berlin: 2001. pp. 129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Razum O, Zeeb H. Suizidsterblichkeit unter Türkinnen und Türken in Deutschland [Suicide risk among Turks in Germany] Nervenarzt. 2004;75:1092–1098. doi: 10.1007/s00115-003-1649-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner W, editor. Austrian experiences with a self-help approach to coping with trauma in refugees from Chechnya. Studia; Innsbruck: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Renner, editor. Female Turkish migrants with recurrent depression. A research report on the effectiveness of group interventions: Theoretical assumptions, results, and recommendations. Studia; Innsbruck (Austria): 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Renner W, Bänninger-Huber E, Peltzer K. Culture-Sensitive and Resource Oriented Peer (CROP)-Groups as a Community Based Intervention for Trauma Survivors: A Randomized Controlled Study with Chechnyans. Australasian Journal of Disaster and Trauma Studies. (accepted) [Google Scholar]

- Renner W, Sladky B. Theoretical Basis I: Women of Turkish Descent in Austria – Psycho-Social and Clinical Aspects. In: Renner W, editor. Female Turkish migrants with recurrent depression. A research report on the effectiveness of group interventions: Theoretical assumptions, results, and recommendations. Studia; Innsbruck (Austria): 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ. Co-rumination in the friendships of girls and boys. Child Development. 2002;73:1830–1843. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Carlson W, Waller EM. Prospective associations of co-rumination with friendship and emotional adjustment: Considering the socioemotional trade-offs of co-rumination. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1019–1031. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin H. Unter unserem Seelenteppich. Lebensgeschichten türkischer Frauen in der Emigration [Under our mental carpet. Biographies of Turkish women in emigration] Studien-Verlag; Innsbruck (Austria): 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sam DL, Berry JW, editors. Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sar V. Dissociative depression: A common cause of treatment resistance. In: Renner W, editor. Female Turkish migrants with recurrent depression. A research report on the effectiveness of group interventions: Theoretical assumptions, results, and recommendations. Studia; Innsbruck (Austria): 2010. pp. xxx–xxx. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab PJ, Tercanli S. Körperliche und seelische Symptome bei Migranten in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Erstellung und Anwendung einer türkischen Fassung der Beschwerdeliste von D. v. Zerssen [Somatic and mental symptoms in migrants in the FRG. Development and application of a Turkish version of the list of complaints by D. v. Zerssen] Psychotherapie und Medizinische Psychologie. 1987;37:419–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sertöz ÖÖ, Mete HE. Obezite Tedavisinde Bilissel Davranisci Grup Terapisinin Kilo Verme, Yasam Kalitesi ve Psikopatolojiye Etkileri: Sekiz Haftalik İzlem Calismasi [Efficacy of cognitive behavioral group therapy on weight loss, quality of life and psychopathology in the treatment of obesity: Eight week follow-up study] Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bülteni [Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology] 2005;15:119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Sleptsova M, Wössmer B, Langewitz W. [Retrieved on 17th August, 2010];Migranten empfinden Schmerzen anders [Migrants feel pain differently] Schweizer Med Forum. 2009 9:319–321. See also http://www.medicalforum.ch/pdf/pdf_d/2009/2009-17/2009-17-017.PDF. [Google Scholar]

- Uzuner Özer G. Adaptation of revised Brief PHQ (Brief PHQ-r) for diagnosis of depression, panic disorder and somatoform disorder in primary health care settings. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 2004;8:11–18. doi: 10.1080/13651500310004452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward C. Acculturation. In: Landis D, Bhagat R, editors. Handbook of intercultural training. 2nd ed Sage; Thousand Oaks: 1996. pp. 124–147. [Google Scholar]

- Westermeyer J. Working with an interpreter in psychiatric assessment and treatment. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1990;178:745–749. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199012000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wössmer B, Sleptsova M. Kultur und Therapie. Schmerztherapie mit türkischsprachigen PatientInnen [Culture and therapy. Pain management with patients of Turkish descent] Psychoscope. 2006;27:101–103. [Google Scholar]