Abstract

To the extent that cultures vary in how they shape individuals’ self-construal, it is important to consider a cultural perspective to understand the role of the self in health persuasion. We review recent research that has adopted a cultural perspective on how to frame health communications to be congruent with important, culturally variant, aspects of the self. Matching features of a health message to approach vs. avoidance orientation and independent vs. interdependent self-construal can lead to greater message acceptance and health behavior change. Discussion centers on the theoretical and applied value of the self as an organizing framework for constructing persuasive health communications.

Keywords: culture, health communications, self-affirmation, approach/avoidance orientations, independence/interdependence

The pancultural nature of health problems leads to the question of whether there are pancultural health solutions. Smoking-related illnesses, sexually transmitted diseases, and oral health problems are issues confronting people all over the world, and can be prevented through changes in health behaviors as they stem fundamentally from issues of self-control and self-regulation (Baumeister & Vohs, 2007). Researchers interested in changing health behaviors thus have an opportunity to reduce death and illness by identifying ways to craft health communications that resonate with important dimensions of the self. In this paper we argue that a cultural consideration of the self, that is, how individuals conceive of themselves in relation to others and their goals and aspirations can provide great utility in the creation of more culturally effective health messages.

Beyond recognizing the importance of examining culture, we build upon existing psychological theories that suggest what features of a health message to vary and what psychological aspects of an individual are the most relevant to target. A growing body of empirical evidence demonstrates that messages are more persuasive when there is a match between the content or framing of a message and the message recipient’s cognitive, affective, or motivational characteristics. For example, messages are more persuasive when they contain content matching one’s attitudes or attitude-relevant thoughts and feelings (e.g., Petty, Wheeler, & Bizer, 2000) motivational orientation (e.g., approach-avoidance orientation, Gerend & Shephard, 2007; Mann, Sherman, & Updegraff, 2004), or regulatory focus (e.g., Cesario, Grant, & Higgins, 2004). Thus, matching health messages to cognitive, affective, and motivational characteristics can help account for the variability in how people respond to health information. As culture influences these psychological characteristics (see Heine, 2010 for a recent review), it suggests the potential benefit of these factors in crafting effective health messages for diverse cultural audiences.

Culture and Self: A Theoretical Basis for Health Message Construction

To account for some of the observed differences between cultures, anthropologists and cultural psychologists have proposed the constructs of individualism and collectivism (e.g., Hofstede, 1980; Triandis, 1995). These constructs have been particularly useful for understanding cultural differences in how people view themselves in relation to others. In individualistic cultures, such as the United Kingdom or the United States, the independent self is the dominant model of the self. This independent self is characterized as possessing self-defining attributes that serve to fulfill personal autonomy and self-expression (Hofstede, 1980; Kim & Sherman, 2007; Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Oyserman, Coon, & Kemmelmeier, 2002; Triandis, 1995). In these cultures, individuals see themselves as agentic and causally determining their decisions and actions. In cultures characterized as individualistic, people are more motivated to pursue opportunities than to not make mistakes, focusing on the positive outcomes they hope to approach rather than the negative outcomes they hope to avoid (e.g., Lee, Aaker, & Gardner, 2000).

By contrast, in collectivistic cultures, such as many East Asian cultures, the dominant model of the self is an interdependent self. This interdependent self is characterized as being embedded within the social context and defined by social relations and memberships in groups (e.g., Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Triandis, 1995). People are more relational or communal and their decisions and actions are heavily influenced by social, mutual obligations and the fulfillment of in-group expectations (e.g., Hofstede, 1980; Oyserman et al., 2002; Triandis, 1995). In such cultures, individuals tend to be motivated to fit in with their group and maintain social harmony (Kim & Markus, 1999); they focus on their responsibilities and obligations while trying to avoid behaviors that might cause social disruptions or disappoint significant others (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). In cultures shaped by collectivism, people are more motivated to not make mistakes than to pursue opportunities, focusing on the negative outcomes they hope to avoid rather than the positive outcomes they hope to achieve (Elliot, Chirkov, Kim, & Sheldon, 2001; Lee et al., 2000; Lockwood, Marshall, & Sadler, 2005). These distinctions in self-construal and self-regulatory tendencies have proven useful for health persuasion.

Crafting Culturally Congruent Health Messages

The goal in crafting culturally congruent health communications is to identify broad characteristics that vary cross-culturally, and to examine whether framing messages to match those characteristics are more persuasive and lead to health behavior change. For example, research based on regulatory focus theory (Higgins, 2000) has found that individuals from collectivistic cultures are more likely to have a prevention focus and be sensitive to the presence or absence of negative outcomes whereas individuals from individualistic cultures are more likely to have a promotion focus and be sensitive to the presence or absence of positive outcomes (Lee et al., 2000). Given this cultural difference, health communications that emphasize the potential losses associated with not performing a behavior may be more effective among those from collectivistic cultures whereas messages that emphasize the potential gains associated with performing a behavior may be more effective among those from individualistic cultures.

Indeed, this distinction between loss-framed messages and gain-framed messages, rooted in Prospect Theory (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981), has yielded broad applicability and utility for health message construction (Rothman & Salovey, 1997). Moreover, at the individual difference level, several studies have now shown that individuals who are dispositionally more avoidance-oriented (a construct similar to, though not isomorphic with prevention focus; see Gable & Strachman, 2008, for discussion) are more persuaded by loss-framed health messages, whereas individuals who are more approach-oriented are more persuaded by gain-framed health messages (Mann et al., 2004; Sherman, Mann, & Updegraff, 2006; see Sherman, Updegraff, & Mann, 2008 for a review). Thus, various lines of research point to the possibility that gain-frame and loss-frame health messages may be differentially effective as a function of culture.

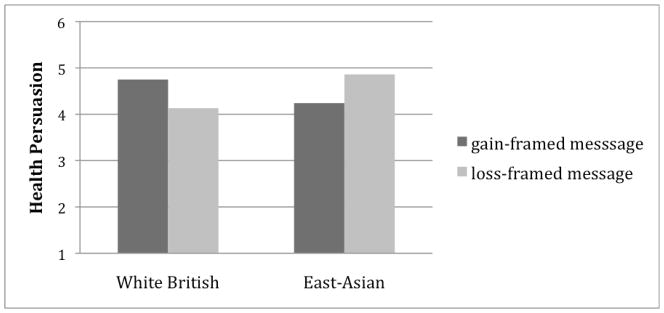

Recent research examined this cultural congruency hypothesis in the domain of dental health (Uskul, Sherman, & Fitzgibbon, 2009). Participants were from either individualistic cultural contexts (e.g., White British) or collectivistic cultural contexts (East Asian) and received one of two messages adapted from flossing recommendations from the British Dental Association that either focused the message on the benefits of flossing (gain-frame; e.g., “If you floss regularly, you will have healthier teeth and gums,”) or the costs of failing to floss (loss-frame; e.g., “If you don’t floss regularly, the health of your teeth and gums is at risk”). The participants from the individualistic culture had more positive attitudes towards flossing and greater intentions to floss when they were presented with the gain-framed message, whereas the participants from the collectivistic culture were more positively affected by the loss-framed message. Figure 1 illustrates these results. The study also adopted a mediated cultural moderation approach and found that the interaction between culture and message framing on persuasion was mediated by an interaction between self-regulatory focus and message frame (Uskul et al., 2009). This finding, and this research approach more generally, permits an examination of how the chronic manner in which people regulate their behavior could account for the relationship between culture and health persuasion.

Figure 1.

Health persuasion (combined measure of attitudes towards health behavior and intentions to change behavior) as a function of culture and message frame.

Recent research has also examined whether matching aspects of the health message to cultural differences in self-construal would lead to greater health persuasion. If individuals with more independent selves are motivated to achieve personal goals, then they should be more motivated to perform health behaviors when the message is framed in terms of personal consequences. Conversely, emphasizing relational consequences may increase the effectiveness of health messages for those with more interdependent selves. Research outside of the health domain has found support for these assertions. For example, Koreans found advertisements that emphasized social norms and roles, and hence were concordant with a more interdependent or relational view of the self, to be more persuasive than advertisements that emphasized more individual preferences and benefits, and hence were concordant with a more independent view of the self. The converse was true for European Americans (Han & Shavitt, 1994; see also Kim & Markus, 1999; Zhang & Gelb, 1996).

Within the health domain, support for this comes from a study by Uskul (2004) that exposed a culturally diverse group of women to an article linking caffeine use to negative health outcomes. The study found that endorsing a strong interdependent self-construal, being in the high relevance group (i.e., consuming a high amount of caffeine), and being exposed to a health message that emphasized interpersonal consequences of caffeine consumption was associated with higher levels of acceptance of detrimental interpersonal effects of caffeine and higher perceived levels of personal risk. Moreover, in another study, Uskul and Hynie (2010) showed that after being exposed to an article describing relational consequences of caffeine consumption, individuals with stronger interdependent self-construal were more likely to take pamphlets focusing on significant others’ health than pamphlets focusing on their own health. Thus, matching health-related information to characteristics of one’s self-construal was associated with increased risk perception or seeking congruent health information.

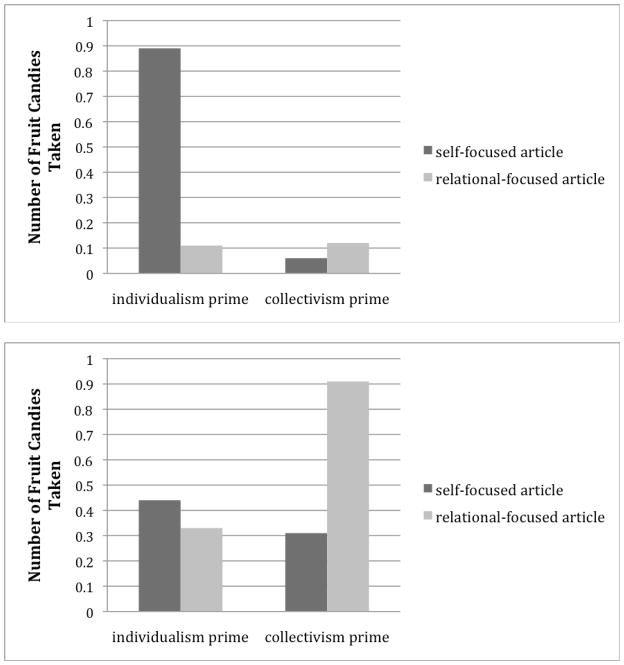

However, it is important to note that in the increasingly diverse multicultural world, people are exposed to multiple cultural influences at different times and therefore different aspects of their self-concept may be salient. Thus, in recent research, Uskul and Oyserman (2010) proposed a culturally informed social cognition framework (see Oyserman & Lee, 2008) that suggests that contextual cues can influence the salience and subsequent influence of culturally shaped orientations. Specifically, they tested the effectiveness of culturally matched health messages about the link between caffeine and fibrocystic disease (following Kunda, 1987; Lieberman & Chaiken, 1992) after making salient the dominant or less dominant self-construal. The results revealed that after being primed for individualism, European Americans who read a health message suggesting a link between caffeine consumption and developing fibrocystic disease that focused on the individual physical consequences (e.g., tenderness and lumps in breasts) were more likely to accept the message – they found it more persuasive, believed they were more at risk and engaged in more message-congruent behavior. These effects were also found among Asian Americans who were primed for collectivism and who read a health message that focused on relational consequences of fibrocystic disease (e.g., not being able to take care of one’s family). Figure 2 illustrates the behavioral findings that European Americans primed with individualism were more likely to opt for the more healthy option (non-caffeinated fruit candies) when given the individual frame, whereas Asian Americans primed with collectivism were more likely to opt for the more healthy option when given the relational frame. Thus, culturally congruent health messages achieved maximum effectiveness when individuals were reminded of their dominant cultural orientation (Uskul & Oyserman, 2010). The findings point to the importance of investigating the role of situational cues in health persuasion and suggest that matching content to a primed frame that is consistent with a chronic frame may maximize effectiveness.

Figure 2.

Number of fruit (i.e., non-caffeinated) candies consumed as a function of cultural prime and focus (self vs. relational) of article for European Americans (on the top) and Asian Americans (on the bottom).

It is important to note, however, that not all findings have found that matching health messages to cultural themes leads to greater persuasion. For example, in one study, a message that focuses on the individual consequences associated with sexually transmitted diseases (e.g., the additional burdens imposed on “my life”) was found to be less effective for European Americans than a message that focused on the relational consequences (e.g., the additional burdens imposed on “my partner” and “my parents”) (Ko & Kim, 2010). Although no differences were found among Asian Americans, this finding is consistent with other research showing that, at times, increased personal relevance may lead to greater defensive processing, particularly for self-threatening health information (Sherman, Nelson, & Steele, 2000). It is important for future research to identify when information framed to be congruent with self-construal leads to greater acceptance vs. greater defensiveness. Moreover, more research is needed to identify the conditions under which self-construal needs to be primed or not to increase the effectiveness of matched health messages.

Crafting Culturally Congruent Self-Affirmations

One psychological strategy that researchers have applied to increase health persuasion is to have people complete self-affirmations in the context of providing them with potentially threatening health information. Self-affirmation theory (Steele, 1988; see also, McQueen & Klein, 2006; Sherman & Cohen, 2006) posits that the goal of the self-system is to maintain an overall image of self-integrity, rather than to respond to specific threats, and thus affirmations of valued domains of self-worth in one part of life are theorized to reduce the need to respond defensively to salient threats in other domains of life. The logic behind this approach is that individuals may respond defensively to threatening health messages, and this itself presents a major barrier in promoting positive health behaviors. For example, recent research points to the possibility that graphic cigarette advertisements designed to create negative associations with smoking can prompt defensive responses and, ironically, lead to an even greater desire to smoke (Hansen, Winzeler, & Topolinski, 2010). Yet, these defensive responses could potentially be reduced when opportunity for self-affirmation is provided.

In the context of smoking, for example, a study was conducted with heavy smokers at a factory in the UK, where researchers presented smokers with a leaflet adapted from the UK government anti-smoking campaign (Armitage, Harris, Hepton, & Napper, 2008). Participants who completed a self-affirmation, that focused them on instances in their life where they had exhibited the value of kindness, had greater acceptance of the anti-smoking information, increased intentions to reduce their smoking behavior, and were more likely to take a brochure with further tips on how to quit smoking, relative to participants in a no-affirmation control condition (for other studies on tobacco use, see Crocker, Niiya, & Mischkowski, 2008; Harris, Mayle, Mabbot, & Napper, 2007).

However, an important question centers on the cultural generalizability of such effects, as prior research has also found that self-affirmations either have no effect among individuals from East Asian cultural contexts (Heine & Lehman, 1997), or that for affirmation manipulations to be effective they need to be matched to the individualistic vs. collectivistic selves of European Canadians and Asian Canadians (Hoshino-Browne et al., 2005). Given the extensive theorizing reviewed above about the ways that cultures vary in how they shape individuals’ self-construal, it seems plausible that different types of self-affirmations may be more or less effective as a function of culture.

A recent study examined the effect of matching the affirmation to the culture of the individual, while keeping the content of the message constant (Sherman, Updegraff, & Uskul, 2010). The affirmations varied in whether they led individuals to focus on approaching positives or avoiding negatives. This distinction was chosen for two reasons. First, health decisions frequently feature approach/avoidance conflicts (e.g., pleasures vs. health risks), and the research reviewed above found that health messages that are congruent with cultural orientations towards approach vs. avoidance are more effective than incongruent messages (Uskul et al., 2009). Second, research has identified cultural differences in the attention people pay to approach-oriented and avoidance-oriented information (Hamamura, Meijer, Heine, Kamaya, & Hori, 2009; Lee et al., 2000). North Americans were more attentive to approach-oriented information and found it to be more helpful, whereas East Asians were more attentive to avoidance oriented information, and found it to be more helpful (Hamamura et al., 2009).

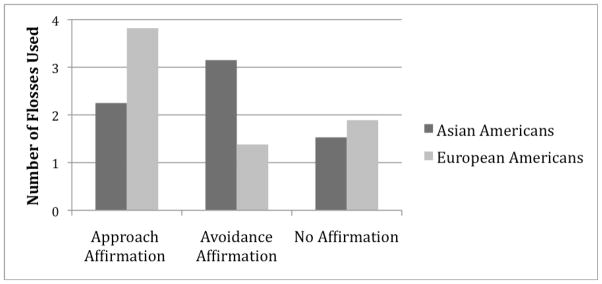

In an experiment (Sherman et al., 2010), European American and Asian American participants ranked values in terms of their personal importance and completed one of three affirmation activities. Those in the avoidance affirmation condition wrote about how their most important value helped them avoid negative things in their life from happening whereas those in the approach affirmation condition wrote about how their most important value helped them obtain positive thing in their life. Participants in the no-affirmation condition completed a standard control condition (McQueen & Klein, 2006). Then, all participants read an article on dental health and the importance of flossing and were given seven individual flosses to use.

The results indicate that an affirmation focused on how values can help people approach positive things was more effective at changing health behaviors amongst European Americans whereas an affirmation focused on how values can help people avoid negative things was more effective among Asian Americans (see Figure 3). Participants flossed more times after reading an article advocating flossing when it was preceded with a self-affirmation that matched their dominant cultural value of approach or avoidance. These findings are consistent with the Hoshino-Browne et al., (2005) findings that matching self-affirmations to dominant cultural values (independence-interdependence) would be more effective at reducing defensiveness. Taken together, along with the extensive research on self-affirmations and health messages, these findings suggest the potential utility of culturally appropriate self-affirmations to increase the acceptance of otherwise threatening health messages in diverse settings.

Figure 3.

Number of dental flosses used as a function of culture and affirmation status.

The Self as an Organizing Framework in Health Persuasion

The self is one of the central constructs in social and personality psychology, and self- and identity-regulation processes directly affect memory, emotion, motivation, and behavior (Baumeister, 1998). As all of these processes are both central to health persuasion and culturally variant (Heine, 2010), the self can provide a useful framework for understanding when social psychological constructs are likely to be effective or ineffective in health persuasion attempts with different cultural groups. The recent research reviewed in this paper illustrates some of the ways that a cultural perspective can enhance the application of existing psychological approaches.

This research review leads to one simple point: We encourage researchers to pay attention to the cultural background of their participants. Collapsing data across cultural groups in the studies described above would have led to null effects of gain vs. loss message framing (Uskul et al., 2009) and approach vs. avoidance self-affirmations (Sherman et al., 2010). Often, when research is conducted in the field or culturally diverse settings, the goal is to replicate established paradigms with higher risk populations, as in the self-affirmation and smoking study conducted with factory workers by Armitage et al. (2008), or a message-framing study on HIV testing targeted at low-income, ethnic minority women (Apanovitch, McCarthy, & Salovey, 2003). There is much to be gained by theoretically examining the psychological characteristics of such diverse samples. This examination can be most profitable, we argue, when a cultural understanding of the self is considered.

The insight of tailoring health messages towards individual differences is not novel, nor is the practice of tailoring health messages to different cultural groups (Kreuter & Haughton, 2006). Research aimed at increasing mammography screenings among African-American women, for example, has shown that featuring African American women in magazine advertisements and emphasizing racial pride (cultural tailoring) and tailoring the message to individual variables (e.g., the level of perceived risk) is more effective at promoting screening than messages that do not include tailored information (Kreuter et al., 2004). Studies such as these (see Kreuter & Haughton, 2006 for review) include large samples of underrepresented populations and important real-world health outcomes. Although the behavioral measures in many of the social psychological studies described in this paper were somewhat limited (e.g., taking decaffeinated candies, brochures, and self-reported flossing), the studies held the advantage of appealing to theoretically-derived constructs, and advancing social psychological theorizing on message-framing, self-affirmation, and approach-avoidance orientation. These studies were also conducted in laboratory contexts that allowed alternative explanations to be controlled. The promise of a more social psychological approach to health persuasion is that a broad set of self-related theories – motivational orientation, self-regulation, self-affirmation, terror management, to name a few – can help inform the development of more effective, culturally-tailored health messages. The present results suggest that benefits of such social psychological approaches for health persuasion may be amplified when the manipulations employed match cultural values of groups and individuals.

Each approach to health persuasion research has benefits that can inform the other. For the social psychological research to have broader applicability, it is imperative to use non-college student samples and broader, more diverse populations. For health communications researchers, we propose that understanding the role of the self may help clarify why particular culturally-tailored interventions are effective or ineffective. Collaborations between those engaged in laboratory experiments and those who conduct large field studies will hopefully yield broader theoretical insights with greater practical utility for reducing health problems in culturally diverse populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cameron Brick, Cynthia Gangi, Kim Hartson, and Heejung Kim for commenting on this paper. This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research #R21 DE019704-01 to the first and third author.

Contributor Information

David K. Sherman, University of California, Santa Barbara

Ayse K. Uskul, University of Essex

John A. Updegraff, Kent State University

References

- Armitage CJ, Harris PR, Hepton G, Napper L. Self-affirmation increases acceptance of health-risk information among UK adult smokers with low socioeconomic status. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:88–95. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apanovitch AM, McCarthy D, Salovey P. Using message framing to motivate HIV testing among low-income, ethnic minority women. Health Psychology. 2003;22:60–67. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.22.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF. The self. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. Handbook of social psychology. Vol. 4. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1998. pp. 680–740. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Vohs KD. Self-regulation, ego depletion, and motivation. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2007;1:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cesario J, Grant H, Higgins TE. Regulatory fit and persuasion: Transfer from “Feeling right”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:388–404. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.3.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Niiya Y, Mischkowski D. Why does writing about important values reduce defensiveness? Self-affirmation and the role of positive, other-directed feelings. Psychological Science. 2008;19:740–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot AJ, Chirkov VI, Kim Y, Sheldon KM. A cross cultural analysis of avoidance (relative to approach) personal goals. Psychological Science. 2001;12:505–510. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gable SL, Strachman A. Approaching social rewards and avoiding social punishments: Appetitive and aversive social motivation. Handbook of motivation science. In: Shah JY, Gardner WL, editors. Handbook of motivation science. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 561–575. [Google Scholar]

- Gerend MA, Shepherd JE. Using message framing to promote acceptance of the human papillomavirus vaccine. Health Psychology. 2007;26:745–752. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamamura T, Meijer Z, Heine SJ, Kamaya K, Hori I. Approach-avoidance motivations and information processing: A cross-cultural analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2009;35:454–462. doi: 10.1177/0146167208329512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Shavitt S. Persuasion and culture: Advertising appeals in individualistic and collectivistic societies. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1994;30:326–350. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen J, Winzeler S, Topolinski S. When the death makes you smoke: A terror management perspective on the effectiveness of cigarette on-pack warnings. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2010;46:226–228. [Google Scholar]

- Harris PR, Epton T. The impact of self-affirmation on health cognition, health behaviour and other health related responses: A narrative review. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2009;3:962–978. [Google Scholar]

- Harris PR, Mayle K, Mabbott L, Napper L. Self- affirmation reduces smokers’ defensiveness to graphic on-pack cigarette warning labels. Health Psychology. 2007;26:437–446. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine SJ. Cultural psychology. In: Fiske ST, Gilbert DT, Lindzey G, editors. Handbook of Social Psychology. Vol. 5. New York: Wiley; 2010. pp. 1423–1464. [Google Scholar]

- Heine SJ, Lehman DR. Culture, dissonance, and self-affirmation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1997;23:389–400. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET. Making a good decision: Value from fit. American Psychologist. 2000;55:1217–1233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G. Culture’s consequences. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino-Browne E, Zanna AS, Spencer SJ, Zanna MP, Kitayama S, Lackenbauer S. On the cultural guises of cognitive dissonance: The case of Easterners and Westerners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:294–310. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.3.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Markus HR. Uniqueness or deviance, harmony or conformity: A cultural analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:785–800. [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Sherman DK. “Express yourself”: Culture and the effect of self-expression on choice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:1–11. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko D, Kim HS. Culture and the effectiveness of personal and relational risk framing of threatening health messages. Health Communication. 2010;25:61–68. doi: 10.1080/10410230903473532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, Haughton LT. Integrating culture into health information for African American women. American Behavioral Scientist. 2006;49:794–811. [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter M, Skinner C, Clark E, Holt C, Steger-May K, Bucholtz D. Responses to behaviorally vs. culturally tailored cancer communication for African American women. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2004;28:195–207. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.28.3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunda Z. Motivated inference: Self-serving generation and evaluation of causal theories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53:636–647. [Google Scholar]

- Lee AY, Aaker JL, Gardner WK. The pleasures and pains of distinct self-construals: the role of interdependence in regulatory focus. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:1122–1134. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.6.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman A, Chaiken S. Defensive processing of personally relevant health messages. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1992;18:669–679. [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood P, Marshall T, Sadler P. Promoting success or preventing failure: Cultural differences in motivation by positive and negative role models. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:379–392. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann T, Sherman D, Updegraff J. Dispositional motivations and message framing: A test of the congruency hypothesis in college students. Health Psychology. 2004;23:330–334. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.3.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review. 1991;98:224–253. [Google Scholar]

- McQueen A, Klein WMP. Experimental manipulations of self-affirmation: A systematic review. Self and Identity. 2006;5:289–354. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Lee SWS. Does culture influence what and how we think? Effects of priming individualism and collectivism. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:311–342. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Coon H, Kemmelmeier M. Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:3–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petty R, Wheeler S, Bizer G. Attitude functions and persuasion: An elaboration likelihood approach to matched versus mismatched messages. In: Maio G, Olson J, editors. Why we evaluate: Functions of attitudes. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 133–162. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman AJ, Salovey P. Shaping perceptions to motivate healthy behavior: The role of message framing. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121:3–19. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman DK, Cohen GL. The psychology of self-defense: Self-affirmation theory. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 38. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2006. pp. 183–242. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman DK, Hartson K. Reconciling self-defense with self-criticism: Self-affirmation theory. Chapter to appear. In: Alicke M, Sedikides C, editors. The handbook of self-enhancement and self protection. Guilford Press; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Sherman DK, Mann T, Updegraff JA. Approach/avoidance orientation, message framing, and health behaviour: Understanding the congruency effect. Motivation and Emotion. 2006;30:165–169. doi: 10.1007/s11031-006-9001-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman DAK, Nelson LD, Steele CM. Do messages about health risks threaten the self? Increasing the acceptance of threatening health messages via self- affirmation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000;26:1046–1058. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman DK, Updegraff JA, Mann T. Improving oral health behavior: A social psychological approach. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2008;139:1382–1387. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman DK, Updegraff JA, Uskul AK. Matching the affirmation to the culture: The effect of culture and approach and avoidance self-affirmations on health persuasion. 2010. Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM. The psychology of self-affirmation: Sustaining the integrity of the self. In: Berkowitz L, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 21. New York: Academic Press; 1988. pp. 261–302. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis H. Individualism and collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science. 1981;211:453–458. doi: 10.1126/science.7455683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uskul AK. Unpublished dissertation. York University; Toronto: 2004. The role of self-construal in illness-related cognitions, emotions, and behavior. [Google Scholar]

- Uskul AK, Hynie M. Unpublished manuscript. University of Essex; 2010. A self-aspects perspective on illness-related emotions and health information seeking behavior. [Google Scholar]

- Uskul AK, Oyserman D. When message-frame fits salient cultural-frame, messages feel more persuasive. Psychology & Health. 2010;25:321–337. doi: 10.1080/08870440902759156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uskul AK, Sherman D, Fitzgibbon J. The cultural congruency effect: Culture, regulatory focus, and the effectiveness of gain- vs. loss-framed health messages. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45:535–541. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Gelb BD. Matching advertising appeals to culture: The influence of products’ use conditions. Journal of Advertising. 1996;25:29–46. [Google Scholar]