Have you ever encountered an elderly patient who developed new, excessively intense interests or compulsive behaviors? Have you ever wondered what might cause such behavioral changes or been perplexed at how to help patients with obsessive thoughts or compulsions? If you have, then the following case vignette of an elderly man who developed progressive compulsive cinephilia (involving obsessions and compulsions with the cinema) and discussion should facilitate the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of patients with similar symptoms.

CASE VIGNETTE

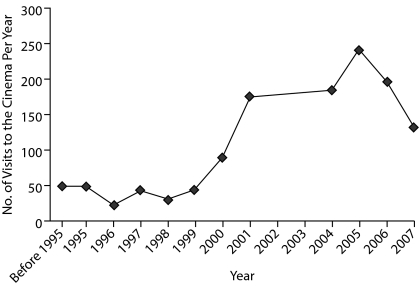

Mr A, a 74-year-old right-handed, hypertensive, former executive, was referred by his wife after 6 years of prominent, progressive, and disruptive behavioral changes; these changes included disinhibition, hoarding bottles of wine, drinking excessively, and compulsively attending and documenting his thoughts about movies (Figure 1). He attended the movies to the detriment of his health and family obligations. Moreover, he had a very rigid, self-imposed schedule; for example, he would go to the same restaurant every day at the same time and order the same meal.

Figure 1.

Evolution of Mr A's Cinephiliaa

aComments and reflections were characterized by a progressive impoverishment of content, from abstract thinking early on to concrete thoughts and agrammatisms as time progressed; data from 2002 and 2003 are not available.

Due to excessive alcohol consumption, which was also a new change in him, Mr A was treated with disulfiram, and his family restricted him from leaving the home. His daily medications and supplements consisted of aspirin, propranolol, and multivitamins. His mother had idiopathic Parkinson's disease, but there was no history of dementia, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), or psychiatric or neurologic illness.

On examination, Mr A was a thin, elderly man without focal neurologic findings. His Mini-Mental State Examination1 score was 30/30. Comprehension, reading, writing, and repetition were intact, and his fluency and prosody were normal. He was neither depressed nor psychotic (ie, there were no hallucinations, illusions, or delusions), and he displayed a full range of affect. However, on formal neuropsychological testing, he showed mild to moderate impairment in executive function, language, and memory. For example, he had psychomotor slowing and difficulties in planning, sequencing, switching between tasks, naming objects, generating word lists, and recalling (even when cued) objects recently presented on a memory task.

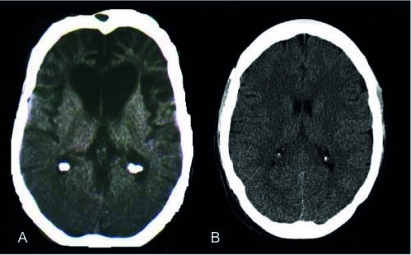

A computed tomography scan of Mr A's head revealed cerebral atrophy, predominantly in the prefrontal regions (Figure 2). He met International Consensus Criteria for behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia (FTD; Table 1).2

Figure 2.

Mr A's Computed Tomography (CT) Scan Showing Severe Bifrontal and Bitemporal Atrophy Compared With a CT Scan of an Individual With No Cortical Atrophya

a(A) Mr A's CT scan reveals severe bifrontal, predominantly prefrontal, as well as bitemporal cortical atrophy. There is associated ex-vacuo dilation of the frontal horns. (B) A CT scan of an individual with no cortical atrophy.

Table 1.

International Consensus Criteria for Behavioral-Variant Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD)a

| Neurodegenerative disease |

| Must be present for any FTD clinical syndrome |

| Shows progressive deterioration of behavior and/or cognition by observation or history |

| Possible behavioral-variant FTD |

| Three of the features (A–F) must be present; symptoms should occur repeatedly, not just as a single instance: |

| A.Early behavioral disinhibition |

| B.Early apathy or inertia |

| C.Early loss of sympathy or empathy |

| D.Early perseverative, stereotyped, or compulsive/ritualistic behavior |

| E.Hyperorality and dietary changes |

| F.Neuropsychological profile: executive function deficits with relative sparing of memory and visuospatial functions |

| Probable behavioral-variant FTD |

| All the following criteria must be present to make the diagnosis: |

| A.Meets criteria for possible behavioral-variant FTD |

| B.Significant functional decline |

| C.Imaging results consistent with behavioral-variant FTD (frontal and/or anterior temporal atrophy on CT or MRI or frontal hypoperfusion or hypometabolism on SPECT or PET) |

| Definite behavioral-variant FTD |

| Criteria A and either B or C must be present to make the diagnosis: |

| A.Meets criteria for possible or probable behavioral-variant FTD |

| B.Histopathological evidence of frontotemporal lobar degeneration on biopsy at postmortem |

| C.Presence of a known pathogenic mutation |

| Exclusion criteria for behavioral-variant FTD |

| Criteria A and B must both be answered negatively; criterion C can be positive for possible behavioral-variant FTD but must be negative for probable behavioral-variant FTD: |

| A.Pattern of deficits is better accounted for by other nondegenerative nervous system or medical disorders |

| B.Behavioral disturbance is better accounted for by a psychiatric diagnosis |

| C.Biomarkers strongly indicative of Alzheimer's disease or other neurodegenerative process |

Adapted with permission from Piguet et al.2

Abbreviations: CT=computed tomography, MRI=magnetic resonance imaging, PET=positron emission tomography, SPECT=single-photon emission computed tomography.

How Can We Understand Mr A's Symptoms?

Mr A experienced a major and progressive change in his behavior and personality over several years. Mr A's most prominent symptoms correspond to the emergence of complex, intentional, and time-consuming behaviors that resulted in interference with previous daily routines; noteworthy was a substantial increase in his number of visits to the cinema (see Figure 1). Mr A's behavior is consistent with compulsive behavior, which can be complex, as exhibited in this case, or simple (eg, repetitive, excessive, or meaningless activities or mental exercises such as hand washing, ordering, checking, praying, counting, and repeating words silently).3,4

Clinical Points

♦Compulsive behaviors can be manifestations of either idiopathic or acquired obsessive-compulsive disorder.

♦In the absence of drugs or other specific medical or psychiatric disorders, new-onset recurrent, disruptive thoughts and behaviors after the age of 50 years should be considered as resulting from a neurologic disorder.

♦While treatment is predicated on the diagnosis, current pharmacotherapy for frontotemporal dementia focuses primarily on symptomatic, neurotransmitter-based treatment.

Compulsive behaviors can be manifestations of either idiopathic or acquired OCD. In idiopathic OCD, compulsions generally prevent or reduce anxiety or distress without providing pleasure or gratification.5 For example, individuals with obsessions about being contaminated may reduce their mental distress by washing their hands until their skin is raw; individuals distressed by obsessions about having left a door unlocked may be driven to check the lock every few minutes; individuals distressed by unwanted blasphemous thoughts may find relief in counting to 10 backward and forward 100 times for each thought. In some cases, individuals perform rigid or stereotyped acts according to idiosyncratically elaborated rules without being able to indicate why they are doing them.5

Mr A's disinhibition and compulsive behavior developed in the absence of a primary psychiatric condition (eg, an anxiety disorder), and this makes his symptoms much more likely to be caused by his neurodegenerative condition and to persist because of impaired insight and judgment and a lack of cortical suppression. Compulsions can occur even when anxiety is not the principal trigger of the recurrent thoughts and behaviors. Indeed, patients with obsessive-compulsive symptoms associated with brain lesions generally are unconcerned about their own problem.6

Who Is at Risk and What Can Cause Late-Onset Obsessions and Compulsions?

In the absence of drugs or other specific medical or psychiatric disorders (eg, OCD), new-onset recurrent disruptive thoughts and behaviors after the age of 50 years should be considered as resulting from a neurologic disease.7 Obsessions and compulsions can result from a wide range of brain disorders, such as vascular lesions, traumatic brain injury, central nervous system infections, and neurodegenerative diseases (Table 2). In patients with few other signs or symptoms of cognitive dysfunction, FTD is the most likely cause. FTD is a neurodegenerative disease that primarily affects the frontotemporal cortex and is the most common neurologic cause of new-onset recurrent thoughts, compulsions, and behaviors in midlife to late life.8 It is characterized by the progressive onset of behavioral disturbances9 that may include obsessions (intrusive thoughts that increase anxiety), compulsions (repetitive, ritualistic behaviors that decrease anxiety), hoarding, motor stereotypies (coordinated movements that have the qualities of purposeful acts), complex tics, self-injurious acts, and perseverations.8 FTD is classified into 3 clinical syndromes: a behavioral variant and 2 language variants (semantic dementia and progressive nonfluent aphasia) on the basis of predominant early symptoms.9

Table 2.

Causes of Late-Onset Obsessions or Compulsions

| Neurodegenerative diseases |

| Frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTD with 3 major variants: behavioral-variant FTD, progressive nonfluent aphasia, semantic dementia) |

| FTD with parkinsonism and motor neuron disease |

| Alzheimer's disease |

| Progressive supranuclear palsy |

| Dementia with Lewy bodies |

| Parkinson's disease with dementia |

| Multisystems atrophy |

| Huntington's disease |

| Corticobasal ganglionic degeneration |

| Mixed dementia (eg, vascular-ischemic dementia, Alzheimer's disease) |

| Cerebrovascular diseases |

| Stroke (basal ganglia) |

| Vascular-ischemic dementia |

| Leukoaraiosis |

| Systemic diseases and metabolic disorders of the brain |

| Metabolic disturbances |

| Nutritional deficiencies (eg, vitamin B12 deficiency) |

| Late manifestation of primary errors of metabolism |

| Porphyria |

| Inflammatory and rheumatologic conditions |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Hashimoto's encephalopathy (ie, steroid-responsive encephalopathy) |

| Brain tumors |

| Frontal meningioma |

| Glioblastoma multiforme |

| Primary central nervous system lymphoma |

| Prion disorders |

| Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease |

| Primary psychiatric disease |

| Major depression |

| Bipolar disorder |

| Other diseases |

| Traumatic brain injury (chronic traumatic encephalopathy) |

| Mitochondrial disorders |

| Chronic subdural hemorrhage |

| Substance abuse (acute and chronic sequelae) |

| Paraneoplastic syndromes |

| Central nervous system infections (eg, HIV, syphilis, toxoplasmosis) |

| Normal pressure hydrocephalus |

| Heavy metal toxicity |

| Unrecognized Asperger's syndrome |

Abbreviation: FTD=frontotemporal dementia, HIV=human immunodeficiency virus

Population-based studies (from The Netherlands) reveal that the prevalence of FTD varies between 2.7/100,000 to 15.1/100,000 (among adults < 65 years in Cambridge, United Kingdom).10 Symptoms of FTD typically present in the sixth decade, although the age at onset varies widely from the third to the ninth decades.11 In Rochester, Minnesota, the incidence of FTD was found to be 3.3/100,000 person-years in the 50- to 59-year age group.12 Familial FTD, implicated in up to 40% of patients with FTD, shows an autosomal dominant pattern in 10% of patients and is more likely to present as behavioral-variant FTD.11 There is no established relationship between age at onset and autosomal dominant forms of FTD, and clinical features also appear to be indistinguishable between familial and sporadic forms of FTD.2

When Does Repetitive Behavior Become Labeled as Abnormal Behavior?

Compulsive and repetitive behaviors (eg, collecting) are (and have been) common among children and adults (eg, collecting art, antiques, books, coins). However, in most cases, we can distinguish normal from abnormal compulsive or collecting behaviors using common sense criteria such as the following: (1) the extent of the repetitive behavior or the accumulated items must be excessive relative to normal behavior and the individual's circumstances; (2) the repetitive behavior must have self-injurious consequences or the collected items may include objects that are of little or no value; (3) the behavior must interfere with normal daily function, either due to the accumulated mass of items or from the nature of the behavior itself; and (4) the repetitive or collecting behavior must have been present for a reasonable period of time and persisted despite attempts by others to curtail the problematic behavior.13 A given compulsive behavior must meet at least 2 of these criteria to be classified as abnormal.

Why Is It Important That We Identify the Cause of Late-Onset Obsessions and Compulsions?

Treatment is predicated upon diagnosis. While FTD may be the cause in the majority of instances, it is important to consider less frequent causes, as they may be reversed with targeted treatments (see Table 2). Therefore, timely diagnosis (valid diagnostic criteria) and referral to a specialist with sufficient expertise to evaluate behavioral changes may guide effective interventions. When presented with cases of progressive cognitive, functional, or behavioral impairments or of late-onset personality and behavioral changes, clinicians are well served by acquiring substantial data from collateral sources (eg, sources who know the patient well) and from the physical examination and laboratory testing. These efforts will help to exclude treatable conditions that may mimic FTD and other neurodegenerative conditions.

The evaluation of FTD should also include cognitive/neuropsychological testing, laboratory assessment (looking for common mimics and exacerbating comorbidities), neuroimaging (eg, brain magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography scans), and spinal fluid analysis.11 Genetic testing is recommended and useful for genetic counseling in patients with autosomal dominant FTD.14 Primary or contributing psychiatric disorders (mainly major depression, anxiety syndromes, bipolar disorder) must also be adequately assessed and treated.

Since obsessions and compulsions are often more disruptive than are memory disturbances or other cognitive deficits, they present a substantial burden to caregivers; such symptoms adversely affect the quality of life for the entire family, as well as their surrounding community. In the appropriate clinical context (eg, midlife or late-late life without other risk factors such as substance abuse, mania, head trauma, or stroke), presence of repetitive behaviors or executive dysfunction should raise one's suspicion for early FTD.15–17 Obsessive-compulsive symptoms commonly herald a diagnosis of FTD.8,18 Since simple, efficient, and accurate tests or biomarkers have yet to be made available to screen for an early diagnosis of dementia (especially in previously high-functioning, intelligent, or highly educated individuals), such consideration is of clinical importance.8,11 FTD, and similar dementing conditions, can be suspected on the grounds of early manifestations, as detected by a careful history.

What Brain Circuits Are Involved in Obsessions and Compulsions in General, and in FTD in Particular?

Repetitive behaviors appear to have their origins in dysfunctional orbitofrontal and basal ganglia circuitry.15 The medial orbitofrontal cortex serves as an important network for several cognitive processes (including the motivation for reward) and stimulus response learning. Functions of the lateral orbitofrontal cortices include involvement in response suppression and motor inhibition.8 Both of these orbitofrontal regions connect with the basal ganglia for the generation of a coherent behavioral stream. Among patients with FTD, simple stereotypical behaviors correlate with right frontal or orbitofrontal hypoperfusion or hypometabolism.19–21 Complex, intentional, or time-consuming compulsions and rigidity correlate with temporal lobe involvement, but they probably affect the closely adjacent orbitofrontal cortex as well.4,22–25

What Should Be Done When FTD Is Recognized?

FTD is an incurable and devastating neurodegenerative illness that affects the entire family.26 Family and caregivers of those with FTD suffer from severe stress.27 As in all dementias, the optimal diagnosis and management of FTD is multimodal and multidisciplinary; it requires early diagnosis and involves a close alliance with caregivers and complex multispecialty care.28,29 The first-line therapy for behavioral disturbances in FTD should be nonpharmacologic, since current drug therapies for FTD are only modestly effective and are associated with serious side effects. An FTD treatment plan that does not include a nonpharmacologic intervention is unlikely to be useful.11

Support groups for caregivers and patients can be invaluable. Informal caregivers (eg, spouses, children, relatives) provide the majority of care to afflicted patients. Providing this 24–7 care, support, and monitoring is stressful, and it adversely affects the health and quality of life of caregivers. A majority of caregivers develop depressive symptoms and anxiety during the course of caregiving. It is not only sensible but also important to focus a sizeable proportion of therapeutic efforts and supports on this group, thus increasing the likelihood of more effective long-term care for afflicted patients.

The multipronged approach to the care of the patient with FTD includes dementia/FTD education; elimination of contributory factors (eg, potentially harmful medications, comorbid medical conditions; treatment of anxiety and depression, optimization of sleep quality; simplification of routines; reduction of stress); shoring of support systems; ensuring personal and public well-being and safety; planning for current and future personal, psychological, medical, and legal needs; optimizing behavioral interventions and strategies; instituting nonpharmacologic interventions; and caring for the patient's caregivers. It is also important to offer genetic counseling to family members; the prevalence of familial FTD is significant, and clinical tests for several gene mutations are available. On this foundation of education, management of expectations, strategic planning, and alliance formation, the clinician should institute a long-term plan for treatment with pharmacologic agents.

Which Pharmacologic Interventions Can Be Applied for FTD?

Current pharmacotherapy for FTD focuses primarily on symptomatic, neurotransmitter-based treatments (Table 3). Unfortunately, no psychotropics were developed specifically for FTD; the rationale for use in FTD is their efficacy in the treatment of similar symptoms in those with primary psychiatric conditions or with other neurodegenerative disorders.11 Of all neurotransmitter-based therapies for FTD, drugs that modify serotonin have the strongest biological rationale, since there is strong evidence for a selective serotonergic deficit in FTD. Further, many of the behavioral symptoms of FTD (eg, depression, compulsions, repetitive behaviors, disinhibition, stereotypical movements, dysregulated eating) respond to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.11,28,30,31

Table 3.

Symptoms and Treatments for Frontotemporal Lobar Degenerationa

| Symptom | Treatment |

| Behavioral disturbances | Caregiver education and support |

| Environmental, physical, and behavioral modificationsb | |

| Antidepressants | |

| Citalopram, escitalopram, sertraline, paroxetine, fluoxetine | |

| Bupropion (with parkinsonism) | |

| Venlafaxine (with prominent apathy) | |

| Antipsychoticsc | |

| Quetiapine (with parkinsonism, motor and sleep disturbances) | |

| Risperidone (with prominent agitation and aggression) | |

| Hypnotics | |

| Trazodone (low dose for sleep initiation) | |

| Melatonin | |

| Antiepileptics | |

| Gabapentin, valproic acid | |

| Other | |

| Lithium | |

| Aphasia | Speech therapy |

| Augmentative communication devices | |

| Parkinsonism | Physical, occupational, and speech therapy |

| Levodopa/carbidopa | |

| Pramipexole, ropinirole | |

| Motor neuron disease | Multidisciplinary treatment |

| Neurologic | |

| Nutritional | |

| Pulmonary | |

| Physical, occupational, and speech therapy | |

| Riluzoled | |

| Bladder dysfunction | Environmental and behavioral modifications |

| Upper motor neuron | Trospium chloride, darifenacin |

| Lower motor neuron | Intermittent catheterization |

Adapted with permission from Rabinovici and Miller.11

Nonpharmacologic therapies are paramount, and drug therapy in isolation is unlikely to be successful. Listed pharmacologic agents are based on the clinical experience of the authors, and all recommendations represent off-label use unless otherwise specified. Medications should always be started at low doses and titrated slowly.

Should be used as last resort and with extreme caution because of increased risk of mortality; there is an FDA black-box warning for the use of antipsychotics in dementia.

FDA approved for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Abbreviation: FDA = US Food and Drug Administration.

The utility of using the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved medications for Alzheimer's disease (ie, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and the noncompetitive N-methyl-d-aspartate agonists, such as memantine) remains equivocal. Although they do provide benefits in slowing the progression of cognitive, functional, and behavioral decline in Alzheimer's disease,32–34 there is less compelling evidence to support their routine clinical use in FTD.11,35,36

Other symptoms (eg, parkinsonism, urinary incontinence, constipation) may be less disruptive but can be equally important; they should be adequately evaluated and treated.11

CONCLUSION

Late-onset changes in behavior, manifest by obsessions and compulsions, should prompt clinicians to investigate a broad differential, as treatment is predicated on etiology. However, recurrent disruptive thoughts and behaviors with midlife to late-life onset are often an early manifestation of FTD, a devastating neurodegenerative condition that warrants evaluation and management. Pharmacologic treatments focus on symptom alleviation. Nonpharmacologic and behavioral interventions play a major role in FTD care and include educating patients and caregivers, monitoring of safety, shoring support systems, planning for current and future health and legal needs, and caring for caregivers. Attention should be focused on caregivers who, over the long-term, shoulder a disproportionate burden of care for this distressing and degenerative illness.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments: The authors thank the patient and his family for participating in this case study (consent was obtained for participation in the study); Josefina Ihnen, BPsych (Santiago, Chile), for transcribing the patient's notebooks; and the Massachusetts General Hospital Clinical Research Education Unit and “Scientific Writing for Publication” seminar series for making this collaboration possible. Ms Ihnen reports no conflicts of interest related to the subject of this article.

Footnotes

Lessons Learned at the Interface of Medicine and Psychiatry

The Psychiatric Consultation Service at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) sees medical and surgical inpatients with comorbid psychiatric symptoms and conditions. Such consultations require the integration of medical and psychiatric knowledge. During their twice-weekly rounds, Dr Stern and other members of the Consultation Service discuss the diagnosis and management of conditions confronted. These discussions have given rise to rounds reports that will prove useful for clinicians practicing at the interface of medicine and psychiatry.

Potential conflicts of interest: Dr Stern is an employee of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine, has served on the speaker's board of Reed Elsevier, is a stock shareholder in WiFiMD (Tablet PC), and has received royalties from Mosby/Elsevier and McGraw Hill. Drs Slachevsky, Nuñez-Huasaf, Blesius, and Atri and Mr Muñoz-Neira report no financial or other affiliations relevant to the subject of this article.

Funding/support: This article was supported in part by PIA-CONICYT, Project CIE-05, University of Chile; National Institute on Aging grant K23AG027171, Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center; and David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Folstein M.F, Folstein S.E, McHugh P.R. Mini-mental state": a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piguet O, Brooks W.S, Halliday G.M, et al. Similar early clinical presentations in familial and non-familial frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(12):1743–1745. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.031948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fornaro M, Gabrielli F, Albano C, et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder and related disorders: a comprehensive survey. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2009;8(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosso S.M, Roks G, Stevens M, et al. Complex compulsive behaviour in the temporal variant of frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol. 2001;248(11):965–970. doi: 10.1007/s004150170049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Psychiatric Association. Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laplane D, Levasseur M, Pillon B, et al. Obsessive-compulsive and other behavioural changes with bilateral basal ganglia lesions: a neuropsychological, magnetic resonance imaging and positron tomography study. Brain. 1989;112(pt 3):699–725. doi: 10.1093/brain/112.3.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiss A.P, Jenike M.A. Late-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder: a case series. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12(2):265–268. doi: 10.1176/jnp.12.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendez M.F, Shapira J.S. The spectrum of recurrent thoughts and behaviors in frontotemporal dementia. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(3):202–208. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900028443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neary D, Snowden J, Mann D. Frontotemporal dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4(11):771–780. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ratnavalli E, Brayne C, Dawson K, et al. The prevalence of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2002;58(11):1615–1621. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.11.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rabinovici G.D, Miller B.L. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. CNS Drugs. 2010;24(5):375–398. doi: 10.2165/11533100-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knopman D.S, Petersen R.C, Edland S.D, et al. The incidence of frontotemporal lobar degeneration in Rochester, Minnesota, 1990 through 1994. Neurology. 2004;62(3):506–508. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000106827.39764.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson S.W, Damasio H, Damasio A.R. A neural basis for collecting behaviour in humans. Brain. 2005;128(pt 1):201–212. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burgunder J.-M, Finsterer J, Szolnoki Z, et al. EFNS. EFNS guidelines on the molecular diagnosis of channelopathies, epilepsies, migraine, stroke, and dementias. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(5):641–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.02985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nyatsanza S, Shetty T, Gregory C, et al. A study of stereotypic behaviours in Alzheimer's disease and frontal and temporal variant frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(10):1398–1402. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.10.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy G.J, Smyth C.A. Screening older adults for executive dysfunction. Am J Nurs. 2008;108(12):62–71. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000341886.15318.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubois B, Slachevsky A, Litvan I, et al. The FAB: a Frontal Assessment Battery at bedside. Neurology. 2000;55(11):1621–1626. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.11.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller B.L, Darby A.L, Swartz J.R, et al. Dietary changes, compulsions and sexual behavior in frontotemporal degeneration. Dementia. 1995;6(4):195–199. doi: 10.1159/000106946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McMurtray A.M, Chen A.K, Shapira J.S, et al. Variations in regional SPECT hypoperfusion and clinical features in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2006;66(4):517–522. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000197983.39436.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosen H.J, Allison S.C, Schauer G.F, et al. Neuroanatomical correlates of behavioural disorders in dementia. Brain. 2005;128(pt 11):2612–2625. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarazin M, Michon A, Pillon B, et al. Metabolic correlates of behavioral and affective disturbances in frontal lobe pathologies. J Neurol. 2003;250(7):827–833. doi: 10.1007/s00415-003-1087-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lo Coco D, Nacci P. Frontotemporal dementia presenting with pathological gambling. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;16(1):117–118. doi: 10.1176/jnp.16.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manes F.F, Torralva T, Roca M, et al. Frontotemporal dementia presenting as pathological gambling. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6(6):347–352. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snowden J.S, Bathgate D, Varma A, et al. Distinct behavioural profiles in frontotemporal dementia and semantic dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70(3):323–332. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.3.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson S.A, Patterson K, Hodges J.R. Left/right asymmetry of atrophy in semantic dementia: behavioral-cognitive implications. Neurology. 2003;61(9):1196–1203. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000091868.28557.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hodges J.R, Davies R, Xuereb J, et al. Survival in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2003;61(3):349–354. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000078928.20107.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mioshi E, Bristow M, Cook R, et al. Factors underlying caregiver stress in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;27(1):76–81. doi: 10.1159/000193626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendez M.F. Frontotemporal dementia: therapeutic interventions. Front Neurol Neurosci. 2009;24:168–178. doi: 10.1159/000197896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piguet O, Hornberger M, Mioshi E, et al. Behavioural-variant frontotemporal dementia: diagnosis, clinical staging, and management. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(2):162–172. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lebert F, Stekke W, Hasenbroekx C, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: a randomised, controlled trial with trazodone. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17(4):355–359. doi: 10.1159/000077171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moretti R, Torre P, Antonello R.M, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: paroxetine as a possible treatment of behavior symptoms: a randomized, controlled, open 14-month study. Eur Neurol. 2003;49(1):13–19. doi: 10.1159/000067021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atri A, Shaughnessy L.W, Locascio J.J, et al. Long-term course and effectiveness of combination therapy in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2008;22(3):209–221. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31816653bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feldman H, Gauthier S, Hecker J, et al. Donepezil MSAD Study Investigators Group. Efficacy and safety of donepezil in patients with more severe Alzheimer's disease: a subgroup analysis from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(6):559–569. doi: 10.1002/gps.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gauthier S, Loft H, Cummings J. Improvement in behavioural symptoms in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease by memantine: a pooled data analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(5):537–545. doi: 10.1002/gps.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bei Hu Ross L, Neuhaus J, et al. Off-label medication use in frontotemporal dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2010;25(2):128–133. doi: 10.1177/1533317509356692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boxer A.L, Lipton A.M, Womack K, et al. An open-label study of memantine treatment in 3 subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(3):211–217. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318197852f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]