Abstract

Endothelial dysfunction is associated with increase in oxidative stress and low NO bioavailability. The eNOS uncoupling is considered an important factor in endothelial cell oxidative stress. Under increased oxidative stress, the eNOS cofactor BH4 is oxidized to dihydrobiopterin (BH2), which competes with BH4 for binding to eNOS, resulting in eNOS uncoupling and reduction in NO production. The importance of the ratio of BH4 to oxidized biopterins versus absolute levels of total biopterin in determining extent of eNOS uncoupling remains to be determined. We have developed a computational model to simulate the kinetics of the biochemical pathways of eNOS for both NO and O2•− production to understand the role of BH4 availability and total biopterin (TBP) concentration on eNOS uncoupling. The downstream reactions of NO, O2•−, ONOO−, O2, CO2 and BH4 were also modeled. The model predicted that a lower [BH4]/[TBP] ratio decreased NO production but increased O2•− production from eNOS. The NO and O2•− production rates were independent above 1.5 µM [TBP]. The results indicate that eNOS uncoupling is a result of a decrease in BH4/TBP ratio and a supplementation of BH4 might be effective only when the BH4/TBP ratio increases. The results from the current study will help understand the mechanism of endothelial dysfunction.

Keywords: Mathematical Model, Kinetic Analysis, eNOS uncoupling, Biopterin ratio, NOS Biochemical Pathway

Introduction

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), which is present in endothelial cells of the vasculature, catalyzes the oxidation of L-Arginine to produce NO [1–3]. Under physiological conditions, NO catalyzes the conversion of GTP to cGMP through stimulation of the enzyme soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) in the vascular smooth muscle cells and dilates the blood vessel [1, 4]. Furthermore, NO prevents platelet aggregation and leukocyte adhesion to endothelium [5–8], thus plays a role in the regulation of vascular permeability [9–11].

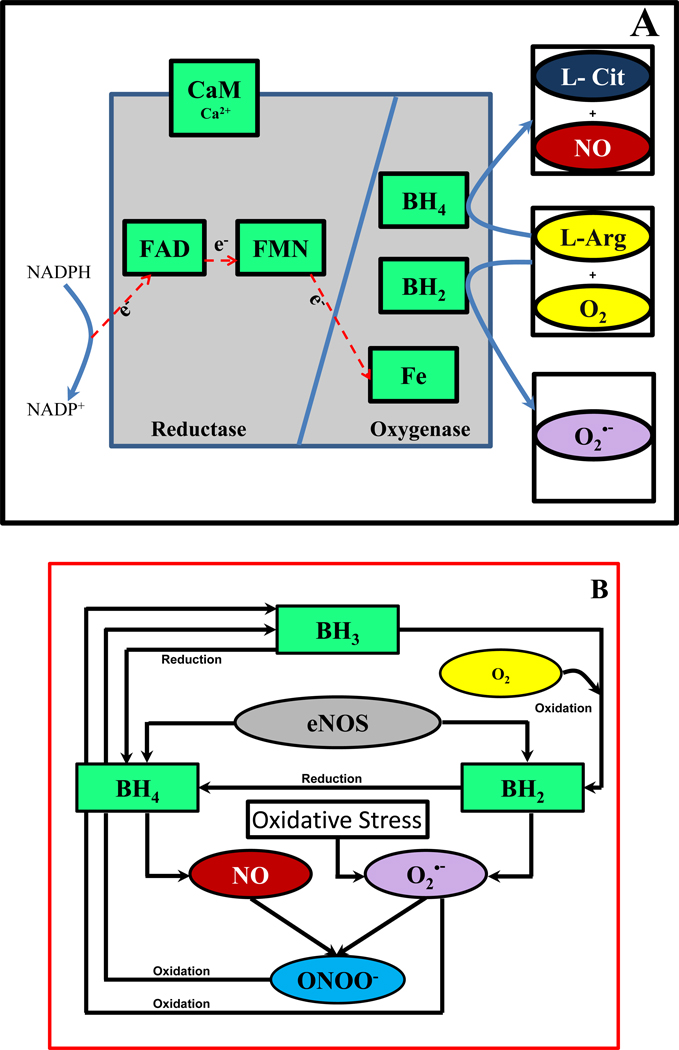

The enzyme eNOS is an oxidoreductase dimer with two domains as shown in Figure 1A [12]. The oxygenase domain contains binding sites for heme, the co-factor biopterin and the substrate L-Arginine [1, 3, 13]. The reductase domain contains binding sites for the flavin co-factors FAD, FMN and the substrate NADPH [1, 3]. The two domains are bound together by a CaM (calmodulin) recognition site [1]. In the presence of Ca2+ and CaM, NADPH oxidizes and donates electrons that migrate along the reductase domain (FAD and FMN) into the oxygenase domain [1, 2, 14]. This causes the catalytic reaction between L-Arginine and O2 to produce NO through a series of biochemical reactions [1]. These reactions can only occur when eNOS is in the dimer form and eNOS is bound to the reduced form of the co-factor biopterin, tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) [3, 15–17]. Furthermore, BH4 promotes the dimerization of eNOS, increases the stability of eNOS and enhances the binding of substrates such as L-Arginine [1].

Figure 1. eNOS structure and [BH4]/[TBP] dependent NO and O2•− production.

Panel A: Structure of eNOS showing the reductase and oxygenase domain with co-factors (light green), substrates L-Arginine and O2 (yellow) and products L-citrulline (blue), NO (red) and O2•− (purple). Panel B: The effects of binding of reduced biopterin (BH4) and oxidized biopterin (BH2) to eNOS on the products of catalytic cycle of eNOS. eNOS binding of BH4 causes NO production and that of BH2 causes production of O2•−. The NO and O2•− formed can react with each other to form ONOO−, which along with O2•− can oxidize BH4 to BH3. The BH3 formed can be oxidized to BH2 by O2.

In pathophysiological conditions including hyperglycemia in diabetes and presence of cardiovascular risk factors, the activity of enzymes such as NADPH oxidases and xanthine oxidase is increased in vascular walls; resulting in an increase in oxidizing species such as superoxide (O2•−) [3, 12, 18, 19]. O2•− reacts with NO to form peroxynitrite (ONOO−) enhancing endothelial oxidative and nitrosative stress. As shown in Figure 1B, both O2•− and ONOO− reduces the endothelial cell BH4 levels by oxidizing BH4 to BH3, which further oxidizes to BH2 [3, 4, 12, 18, 19]. BH2 can also compete with BH4 for binding to the oxygenase domain of eNOS [4, 20]. The binding of BH2 to eNOS causes uncoupling of eNOS. The uncoupling of eNOS is reported to increase the O2•− production and decrease the NO production [4, 19, 21]. The uncoupling of eNOS can also occur due to failure of eNOS to form dimers [3]. In such cases, the NADPH donated electrons directly reduces O2 to O2•−. However, the O2•− generation from monomeric NOS is small in comparison to that seen from the uncoupled dimeric eNOS [3].

Several studies have investigated the role of BH4 oxidation to BH2 and subsequent reduction in BH4 availability on eNOS uncoupling. However, the relative importance between biopterin ratio (the ratio of BH4 to oxidized biopterins) and absolute levels of total biopterin (TBP) in determining extent of eNOS uncoupling remains unresolved [18]. Vasquez-Vivar et al. [4, 22] and Crabtree et al. [19, 23] reported the importance of biopterin ratio whereas Alp et al. [24] reported that both absolute biopterin levels and biopterin ratio are important to determine the extent of eNOS uncoupling. In addition, it has also been reported that the absolute levels of BH4 and not the biopterin ratio is the principal determinant of eNOS activity and uncoupling [25].

In vitro BH4, BH2 and sepiapterin supplementation studies performed on either cultured endothelial cells, isolated blood vessel segments and tissues under both normal and diseased conditions have shown an increase in the total biopterin levels (TBP) [23, 26–29]. The biopterin ratio (ratio between reduced (BH4) and oxidized biopterin (BH2 and BH3)) was found to decrease upon supplementation of BH4 under diseased conditions [23, 26]. Under normal physiological conditions, BH4 supplementation either had no effect on biopterin ratio or decreased biopterin ratio [23, 26, 29]. Supplementation of BH2 in cultured endothelial cells under high and low glucose showed an increase in biopterin ratio for high glucose treated endothelial cells. The endothelial cells cultured under normal glucose levels had no effect on the biopterin ratio [23]. In another in-vitro study performed on intestinal epithelial cells under normal conditions, BH2 supplementation was found to decrease the biopterin ratio [29]. Sepiapterin supplementation led to decrease in biopterin ratio under normal conditions [30]. In disease conditions supplementation of sepiapterin helped in maintaining the biopterin ratio, which was found to decrease when the BH4 producing enzyme GCH-1 was inhibited [30].

The physiological effects of BH4, BH2 and sepiapterin supplementation on biopterin ratio have also been demonstrated in several studies. Studies involving high dose BH4 supplementation in hypertensive individuals [31] and in patients with heart failure [32] resulted in significant improvement in their forearm blood flow. Other BH4 supplementation studies involving patients with hypercholesterolemia [33], diabetes [34] and those subjected to cardiac catheterization for complications such as atherosclerosis [35] and hypercholesterolemia [36] showed significant improvement in their endothelial function. In some cases however, prolonged BH4 supplementation led to worsening of endothelial function as was observed in isolated cerebral arteries [27] and canine basilar arteries [37] and the oxidation of BH4 to BH2 was identified as the primary cause of reduced endothelial function. Supplementation of sepiapterin on vessels of apoE-KO mice improved endothelial function and reduced O2•− production [38]. Incubation of porcine and human atherosclerotic vessels with sepiapterin showed improvement in endothelial vasodilation [39]. On the contrary it was found that incubation of hyperlipidemic rabbit vessels with high concentration of sepiapterin caused an increase in O2•− production, decrease in NO production and impaired endothelial dependent vasodilation. [40].

Vasquez-Vivar et al. [4] reported that an addition of 2 µM BH4 to purified BH4 free eNOS results in 97% of maximal NO production of 145 nmol.min−1.mg eNOS−1. Subsequent addition of 2 µM BH2 inhibits the NO production to 50% of its maximal value. In addition, the addition of BH2 at 14 µM increases eNOS based O2•− production to 50% of maximal O2•− production of 49 nmol.min−1.mg eNOS−1. In high glucose exposed endothelial cells, Crabtree et al. [23] reported that the addition of BH4 decreases the biopterin (BH4:BH2) ratio and increases the total biopterin levels. They also observed significant decrease in NO production and increase in O2•− production.

The primary causes of endothelial dysfunction is an increased production of O2•− and reduced NO availability in endothelial cells. A critical step in our understanding of mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction is to analyze the eNOS biochemical pathways leading to either NO or O2•− formation. Based on the kinetic approach, the eNOS catalysis mathematical models have been developed [41, 42]. These eNOS catalysis modeling studies focused on the reactions involving the oxidation of L-Arginine for NO production. The important results of these studies include steady state NO production rates ranging from 0.003 µM.s−1 for EC based eNOS concentration of 0.008 µM to 0.034 µM.s−1 corresponding to EC based eNOS concentration of 0.097 µM [41]. The analysis of Santolini et al. [42] showed that the NO concentration increased linearly during the first minute of eNOS catalysis from 0 µM to approximately 0.4 µM for eNOS concentration of 1 µM. Over longer time span (15 minutes), the eNOS concentration of 0.25 µM resulted in a non-linear increase in NO concentration from 0 µM to approximately 8 µM and the steady state is not achieved in the time span.

In order to provide a better insight as to how biopterin forms can affect endothelial dysfunction, it is important to model the O2•− production pathways for eNOS along with the already established NO production pathways and correlate them with biopterin (BH4 or BH2) availability. In this study, a mathematical model has been presented to account for the biochemical pathways of eNOS for both NO and O2•− production for the first time. In addition, an analysis of biopterin (BH4 or BH2) availability to predict the NO and O2•− production rates is presented. The model also accounts for the reaction involving NO and O2•− to form ONOO− as well as the oxidation of reduced biopterin (BH4) by both O2•− and ONOO−. The current study also addresses the relative importance between the biopterin ratio (BH4:BH2) and the absolute levels of total biopterin (TBP) on the extent of dimeric eNOS uncoupling.

Materials and Methods

Model Description

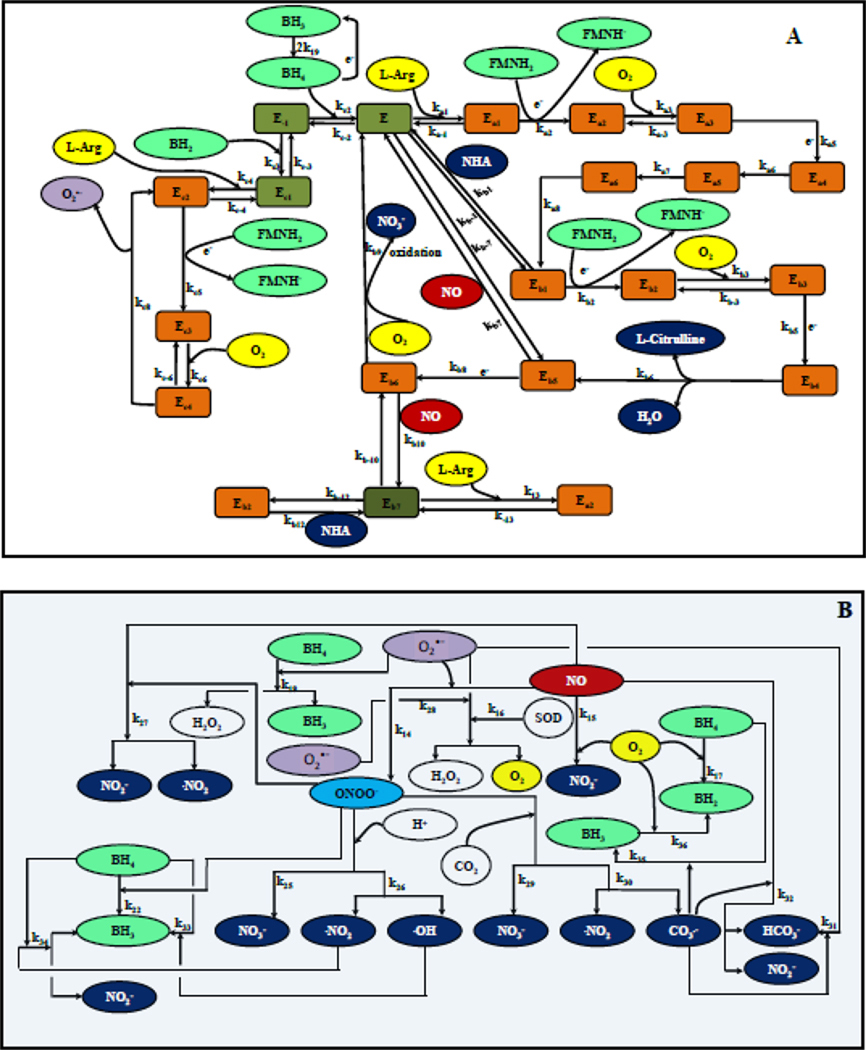

Using known biochemical pathway for eNOS, NO production was modeled for a single endothelial cell [41, 42]. For eNOS uncoupling and O2•− production, we used biochemical pathway described by Berka and co-workers [43, 44] In brief, the electron transport from reductase to oxygenase domain in eNOS occurs after biopterin binds to the enzyme [1]. Following the binding of biopterin, L-Arginine and CaM to NOS dimer, the heme in the oxygenase domain undergoes a series of redox reactions to produce NO and O2•− as shown in Figure 2A. The production of NO and O2•− is dependent on the availability of oxidized biopterin (BH2) and reduced biopterin (BH4). Furthermore, NO and O2•− can react with each other to form ONOO−. ONOO− can participate in several redox reactions shown in Figure 2B [45].

Figure 2. Schematic of the reaction pathways associated with eNOS.

Panel A shows the biochemical pathways of eNOS related to the production of NO by oxidation of L-Arginine upon binding of BH4 to eNOS as well as the biochemical pathway associated with the production of O2•− upon binding of BH2 to eNOS. Green represents the co-factors, grey the enzyme, orange the enzyme substrate complexes, yellow the substrates, blue, red and purple represent the products of eNOS catalysis i.e. NHA (blue), L-citrulline (blue), NO (red) and O2•− (purple). Panel B shows the reactions associated with NO, O2•− and their mutual reaction product peroxynitrite (ONOO−) as well the reactions associated with O2 and CO2 and the different forms of biopterin (BH4, BH3 and BH2).

Overall, these reactions can be classified into three major biochemical pathways of 1) NO production, 2) O2•− production, and 3) downstream reactions involving NO, O2•− and ONOO−. The biochemical pathway for eNOS based NO production proceeds when BH4 is bound to eNOS. The NO production pathway involves oxidation of L-Arginine to N-hydroxyl-L-Arginine (NHA) and subsequent oxidation of NHA to NO and citrulline. Binding of BH2 to eNOS leads to a separate biochemical pathway leading to production of O2•−. The first three reactions in the biochemical pathway of eNOS based O2•− production following binding of BH2 to eNOS are similar to the first three reactions in the biochemical pathway of eNOS based NO production when BH4 is bound to eNOS. The nomenclature of the different forms of eNOS and the eNOS substrate complexes during NO and O2•− production is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Enzyme substrate complex nomenclature for eNOS

| Nomenclature | Enzyme/Enzyme Substrate complex |

|---|---|

| E−1 | eNOS-(FeIII) |

| Ec1 | eNOS-(FeIII)-BH2 |

| Ec2 | eNOS-(FeIII)-BH2-Arg |

| Ec3 | eNOS-(FeII)-BH2-Arg |

| Ec4 | eNOS-[FeII-O2]-BH2-Arg / eNOS-[FeIII-O2−]-BH2-Arg |

| E | eNOS-(FeIII)-BH4 |

| Ea1 | eNOS-(FeIII)-BH4-Arg |

| Ea2 | eNOS-(FeII)-BH4-Arg |

| Ea3 | eNOS-[FeII-O2]-BH4-Arg or eNOS-[FeIII-O2−]-BH4-Arg |

| Ea4 | eNOS-[FeIII-OOH]-BH3-Arg |

| Ea5 | eNOS-[FeIV-O]-BH3-Arg |

| Ea6 | eNOS-(FeIII)-BH3-NHA |

| Eb1 | eNOS-(FeIII)-BH4-NHA |

| Eb2 | eNOS-(FeII)-BH4-NHA |

| Eb3 | eNOS-[FeII-O2]-BH4-NHA / eNOS-[FeIII-O2−]-BH4-NHA |

| Eb4 | eNOS-[FeIII-OOH]-BH3-NHA |

| Eb5 | eNOS-(FeIII)-NO-BH4 |

| Eb6 | eNOS-(FeII)-NO-BH4 |

| Eb7 | eNOS-(FeII)-BH4 |

The downstream reactions involving NO, O2•− and their reaction product ONOO− include auto-oxidation of NO by O2, dissociation of peroxynitrous acid (ONOOH), reaction between ONOO− and CO2, reaction between ONOO− and NO, O2•− dismutation, oxidation of BH4 and BH3 to BH2 by O2 and oxidation of BH4 to BH3 by O2•−, ONOO− and radicals formed from the reaction between ONOO− and CO2 and dissociation of ONOOH. Details of all the reactions for the biochemical pathways of NO and O2•− production and the downstream reactions involving NO, O2•− and ONOO− are shown in Appendix A1.1.

The kinetic model was developed for dimeric eNOS and the production of O2•− from eNOS monomers was ignored. This is due to the fact that the O2•− generation from monomeric NOS is small in comparison to that of with uncoupled dimeric eNOS [3]. The large variation in morphology and sizes of the endothelial cells could have an effect on the intracellular concentration of eNOS. We analyzed the effect of eNOS concentration on the NO and O2•− production rates.

Previous studies have shown that majority of the intracellular eNOS is located on endothelial cell membrane [14, 46, 47]. Cytosolic eNOS, if at all present, is inactive [14]. We assumed that only membrane bound eNOS was responsible for production of NO and O2•−. Species (NO and O2•−) transport within and through the EC was not taken into consideration. An earlier study by Chen and Popel [41] of computational analysis for the kinetics of eNOS based NO production has shown that the NO production rate is independent of the geometrical location of eNOS within the cell. Thus, the kinetics of eNOS based reactions for the biochemical pathways of NO and O2•− production is reasonable approximation for predictions of eNOS related NO and O2•− production in endothelial cells.

Model Formulation

The model developed in this study accounts for the mass conservation of the enzyme (eNOS), which was a simplification in earlier kinetic modeling studies related to the biochemical pathways of eNOS [41, 42]. Furthermore, the total biopterin (BH4, BH3 and BH2) is conserved. To account for the conservation of eNOS and total biopterin, one of the intermediate rate equations for eNOS complex and the rate equation for BH2 is in the form of algebraic equations. Apart from the two algebraic equations, there are 32 different rate expressions for the 32 chemical species in the biochemical and downstream pathways involving NO and O2•− production. The rate equations are in the form of ordinary differential equations (a total of 32 differential equations). Appendix A1.2 lists the justifications behind the use of 34 model equations along with the model equations in their mathematical form.

Model Parameters

The model parameters of concentrations and rate constants are shown in Table 2 and 3, respectively. The eNOS concentration of 0.097 µM was assumed, which is based on the reported eNOS concentration of 5137 pg/106cells in HUVECs [41] and a single EC volume of 400 µm3 [41]. Werner-Felmayer et al. [48] measured the BH4 concentration of 2.6 pmol/106cells in HUVEC cells under normal physiological conditions. Thus, the BH4 concentration was calculated to be 6.5 µM using the volume of a single EC. A small fraction (5–10 %) of total biopterin (TBP) is in oxidized form under normal physiological conditions [23, 25]. The concentration of total biopterin (TBP) was assumed to be 7 µM. In the current study, the concentrations of BH4 and TBP were constant for the entire time span. Thus, the simulation had a constant BH4/ total oxidized biopterin (sum of BH2 and BH3) ratio. Though the total oxidized biopterin was constant for a simulation, BH2 and BH3 concentrations were varying with time.

Table 2.

Parameters related to eNOS kinetics for NO/O2− production

| Variable/Constant | Values | Units | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vmax | 0.585 | µmol/min/mg | [55] |

| [Ca2+] | 0.013–0.280 | µM | [54, 57] |

| [eNOS] | 0.007–0.097 | µM | [41, 82] |

| [NADPH] | 166–295 | µM | [54] |

| [CaM] | 5 | µM | [56] |

| [L-Arginine] | 0.1–1 | mM | [51] |

| [O2] (arterioles) | 127–172 | µM | [41, 52] |

| [O2] (venules) | 50–80 | µM | [41, 52] |

| Km (NADPH) | 0.65 | µM | [55] |

| Km (O2) | 7.7 | µM | [83] |

| Km (L-Arginine) | 2.9–5 | µM | [51, 55] |

| EC50 (Ca2+) | 0.11 | µM | [55] |

| EC50 (CaM) | 0.009 | µM | [55] |

Table 3.

Rate constants for biochemical reactions for production and interactions of NO and O2•−

| Constant | Reported Values |

Experimental Conditions |

Value at 37°C | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ka1 (M−1.s−1) | 2 × 105 8 × 105 |

4°C 23°C |

1.19×106 | [44, 84] |

| ka−1 (s−1) | 0.08 1.6 |

4°C 23°C |

3.77 | [44, 84] |

| ka2 (s−1) | 0.17 | 10°C | 0.474 | [42] |

| ka3 (M−1.s−1) | 2.65 × 105 3.4 × 105 |

7°C 10°C |

8.20×105 | [71, 72] |

| ka−3 (s−1) | 24 28 |

7°C 10°C |

48.3 | [71, 72] |

| ka5 (s−1) | 6.2 6.5 ± 1.5 |

7°C 10°C |

7.68 | [72, 85] |

| ka6 (s−1) | ≥ ka5 | Same as ka5 | 7.68 | [16] |

| ka7 (s−1) | 5.8 ± 1.7 | 10°C | 6.85 | [85] |

| ka8 (s−1) | 1.3 | 10°C | 3.62 | [73] |

| kb1 (s−1) | 0.08 1.6 |

4°C 23°C |

0.1 | [84] |

| kb−1 (M−1.s−1) | 2×105 8×105 |

4°C 23°C |

1×105 | [84] |

| kb2 (s−1) | 0.17 | 10°C | 0.474 | [42] |

| kb3 (M−1.s−1) | 3.42 × 105 | 7°C | 9.19×105 | [72] |

| kb−3 (s−1) | 22 | 7°C | 40.5 | [72] |

| kb5 (s−1) | 31 ± 3.2 | 10°C | 36.6 | [74] |

| kb6 (s−1) | 8 | 10°C | 9.45 | [74] |

| kb7 (s−1) | 2.5 3.5 ± 0.5 |

7°C 10°C |

11.5 | [42, 72] |

| kb−7 (M−1.s−1) | 6.1 × 105 | 10°C | 1.7×106 | [71] |

| kb8 (s−1) | (2.8 ± 0.4) × 10−3 | 10°C | 7.8×10−3 | [42] |

| kb9 (s−1) | 0.63 ± 0.05 | 10°C | 1.76 | [42] |

| kb10 (s−1) | (6.3 ± 1.0) × 10−4 | 10°C | 1.76×10−3 | [42] |

| kb−10 (M−1.s−1) | 1.1 × 106 | 10°C | 3.07×106 | [71] |

| kb12 (s−1) | 0.08 1.6 |

4°C 23°C |

3.66 | [84] |

| kb−12 (M−1.s−1) | 2 × 105 8 x105 |

4°C 23°C |

1.09×106 | [84] |

| k13 (M−1.s−1) | 2 × 105 8 ×105 |

4°C 23°C |

1.19×106 | [41, 84] |

| k−13 (s−1) | 0.08 1.6 |

4°C 23°C |

3.77 | [41, 84] |

| kc2 (M−1.s−1) | 0.22 × 105 | 37°C | 2.20×104 | [75] |

| kc−2 (s−1) | 0.005 | 37°C | 0.005 | [75] |

| kc3 (M−1.s−1) | 0.22× 105 | 37°C | 2.20×104 | [75] |

| kc−3 (s−1) | 0.047 | 37°C | 0.047 | [75] |

| kc4 (M−1.s−1) | 2 × 105 8 ×105 |

4°C 23°C |

1.19×106 | [44, 84] |

| kc−4 (s−1) | 0.08 1.6 |

4°C 23°C |

3.77 | [44, 84] |

| kc5 (s−1) | 0.17 | 10°C | 0.474 | [21, 50] |

| kc6 (M−1.s−1) | (3.2±1.4) × 105 4.52 × 105 |

4°C 7°C |

1.73×106 | [43, 72] |

| kc−6 (s−1) | 7.2±3.1 | 4°C | 14.2 | [43] |

| kc8 (s−1) | 0.15 0.181 |

4°C 7°C |

0.375 | [43, 72] |

| k14 (M−1.s−1) | 6.7 × 109 | 37°C | 6.7×109 | [65] |

| k15 (M−2.s−1) | 2.4 × 106 | 37°C | 2.4×106 | [60] |

| k16 (M−1.s−1) | 2.5 × 109 | 25°C | 3.85×109 | [65] |

| k17 (M−1.s−1) | 0.60±0.03 | 37°C | 0.6 | [20, 79] |

| k18 (M−1.s−1) | 3.9 × 105 | 37°C | 3.9×105 | [79] |

| k19 (M−1.s−1) | 4.65 × 104 | 37°C | 4.65 × 104 | [79, 81] |

| k22 (M−1.s−1) | 6 × 103 | 37°C | 6 × 103 | [58] |

| k25 (s−1) | 0.568 | 22°C | 0.981 | [60] |

| k26 (s−1) | 0.232 | 22°C | 0.401 | [60] |

| k27 (M−1.s−1) | 9.1 × 104 | 37°C | 9.1 × 104 | [65] |

| k28 (M−1.s−1) | 2.54×105 | 25°C | 3.57×105 | [60] |

| k29 (M−1.s−1) | 3.886 × 104 | 37°C | 3.886 × 104 | [60] |

| k30 (M−1.s−1) | 1.914 × 104 | 37°C | 1.914 × 104 | [60] |

| k31 (M−1.s−1) | 4 × 108 | 23°C | 6.65 × 108 | [60] |

| k32 (M−1.s−1) | 3.5 × 109 | 23°C | 5.82 × 109 | [60] |

| k33 (M−1.s−1) | 8.8 × 109 | 37°C | 8.8 × 109 | [81] |

| k34 (M−1.s−1) | 9.4 × 108 | 37°C | 9.4 × 108 | [81] |

| k35 (M−1.s−1) | 4.6 × 109 | 37°C | 4.6 × 109 | [81] |

| k36 (M−1.s−1) | 3.2 × 103 | 37°C | 3.2 × 103 | [79] |

| k37 (M−2.s−1) | 6 × 108 | 37°C | 6 × 108 | [59] |

| k38 (M−1.s−1) | 1.35 × 103 | 37°C | 1.35 × 103 | [59] |

| k39 (M−1.s−1) | 6.6 × 107 | 37°C | 6.6 × 107 | [59] |

| Km,GR (µM) | 50 | 37°C | 50 | [59] |

| Vm,GR (M.s−1) | 3.2 × 10−4 | 37°C | 3.2 × 10−4 | [59] |

Oxidation of BH4 by oxidants such as O2•−, ONOO− and radicals such as •OH, •NO2 and CO3•− convert BH4 to an intermediate radical known as BH3. BH3 and BH4 undergo autoxidation in a two step process. In the first step BH4 or BH3 is oxidized to an intermediate form called quinonoid BH2 (qBH2) [20, 49]. The qBH2 depending upon pH and temperature can either undergo self rearrangement to form a more stable isomer 7,8 dihydro-L-biopterin (7,8-BH2) or eliminate the side chain in 6 position to form 7,8-dihydropterin (7,8-PH2), which can be rapidly hydrated to form other species including dihydroxanthopterin [49]. Previous studies have shown that the different isoforms of BH2 bind to NOS with similar affinities [4, 20, 50] and increase NOS based superoxide production [4, 22]. We thus assume a generalized form of dihydrobiopterin (BH2) as the final product of BH4 oxidation, which accounts for 7,8 BH2, 7,8-PH2 and dihydroxanthopterin.

The L-Arginine concentration was assumed to be 100 µM, which is the lower limit of the reported intracellular L-Arginine concentration of 0.1 to 1 mM in EC’s [51]. The O2 concentration was assumed to be 140 µM [52]. We assumed CO2 concentration to be 1.1 mM [53]. The SOD concentration was assumed to be 10 µM based on the intracellular SOD concentration of 4–10 µM reported by Beckmann and Koppenol [45]. The NADPH concentration was calculated to be 166–295 µM based on the reported value of 66.3–117.9 pmol/106 EC’s in rat endothelial cells by Meininger et al. [54]. The Km of NADPH is 0.65 µM [55]. Persechini and Stemmer [56] reported the concentration of CaM in EC’s to be approximately 5 µM, which is several orders of magnitude above its EC50 value of 0.009 µM [55]. Wickham et al. [57] reported the Ca2+ concentration of 0.218 µM in HUVEC cells, which closely matches its EC50 value of 0.11 µM [55]. Therefore, we assumed an excess of NADPH, CaM and Ca2+.

The rate constant for most of the reactions were obtained from literature. The rate constants measured at lower temperatures were scaled up to the physiologically relevant temperature of 37°C using the Arrhenius equation as shown below

| (1) |

where, k (T2) represents the rate constant calculated at the scaled up temperature (T2) (usually 37°C or 310 K) and k (T1) represents the rate constant at the temperature at which it was measured (T1). R represents the universal gas constant (8.314 J.mol−1.K−1). Ea is the activation energy (J.mol−1). When the rate constants were available at two distinct temperatures, the activation energy was obtained using Arrhenius equation. The estimated activation energy can then be used for scaling up the respective rate constant corresponding to 37°C. Chen and Popel [41] reported that when either L-Arginine or NHA is bound to eNOS, the eNOS complexes pair including the O2 binding to ferrous (Fe2+) heme, O2 dissociation from the heme dioxy complex (Fe3+-O2−) and conversion of the heme back to ferric (Fe3+) state are structurally similar. Therefore, the following pairs of rate constants ka3 and kb3, ka−3, kb−3 and kc−6, ka5 and kb5, and ka6 and kb6 were assumed to have similar activation energies. There were insufficient experimental rate constant data for ka2, ka8, kb2, kb−7, kb8, kb9, kb10, kb−10, kc5, k16, k23, k24, k25, k26, k28, k31 and k32. The activation energy for these rate constants was assumed to be 27690.79 J.mol−1, which is the average of the other known activation energies used in this study.

Numerical Solution

The rate equations as shown in the Appendix A1.2 along with the appropriate initial conditions were solved numerically using the MATLAB (Mathworks Inc, Natick, MA) ODE (ordinary differential equation) solver ode15s. The relative and absolute error tolerance values were set at 1e−10 and 1e−15 respectively. The simulations were run for 1×104 s. To obtain the steady state values, the model was run for 3–5×104 s in some cases.

Results

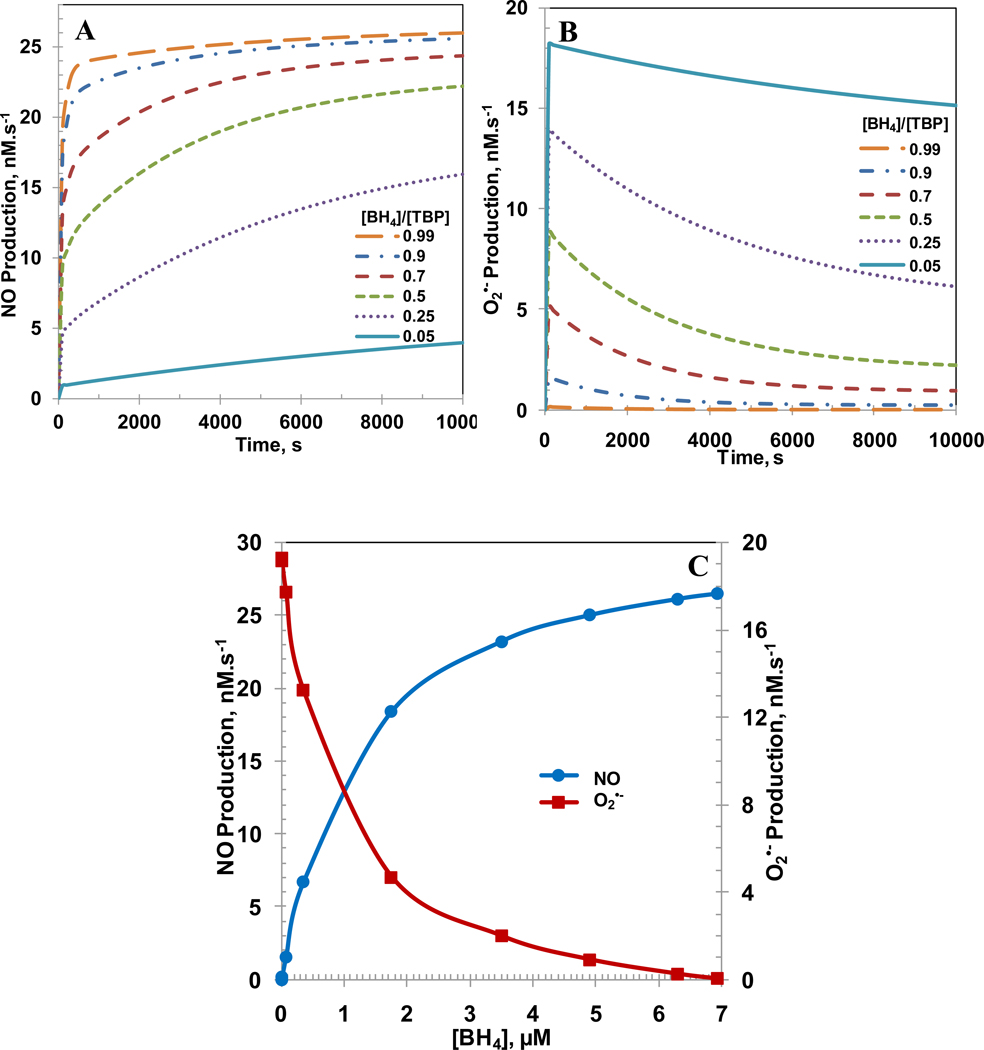

NO production decreases and O2•− production increases nonlinearly with a reduction in tetrahydrobiopterin availability

In normal physiological conditions, a small amount (5–10%) of total biopterin is in oxidized biopterin (BH2 and BH3) form [23, 25]. However, the amount of oxidized biopterin can increase as much as 90% in endothelial cell dysfunction [23, 25]. To understand the impact of BH4 availability on the NO and O2•− productions from eNOS; six cases were simulated with [BH4]/[TBP] ratio from 0.99 to 0.05. A high value for the ratio indicates that the majority of total biopterin (TBP) is in the reduced form BH4 (normal function) whereas a low value for the ratio indicates that the majority of total biopterin is in the oxidized forms BH3 and BH2 (dysfunction). The concentrations of eNOS, TBP, L-Arginine and O2 were 0.097, 7, 100 and 140 µM, respectively. The SOD and CO2 concentrations were set at 10 µM and 1.1 mM, respectively. Figure 3A and B show the NO and O2•− productions, respectively for [BH4]/[TBP] ratios of 0.99, 0.90, 0.70, 0.5, 0.25 and 0.05. A decrease in [BH4]/[TBP] ratio decreased the NO production and increased the O2•− production. For [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.99, 0.9, 0.7, 0.5, 0.25 and 0.05 at 10,000 s, the NO production was 26.0, 25.6, 24.4, 22.2, 15.9 and 4.0 nM.s−1, respectively and the O2•− production was 0.02, 0.3, 1.0, 2.2, 6.1 and 15.1 nM.s−1, respectively. The decrease in [BH4]/[TBP] ratio also increased the time required to attain steady state. The steady state NO and O2•− productions are shown in Figure 3C with respect to absolute BH4 concentration. The increase in BH4 concentration in Figure 3C also represents the increase in [BH4]/[TBP] ratio since the total biopterin concentration ([TBP]) is maintained at 7 µM. As seen, both the decrease in the NO production and increase in O2•− production are nonlinear with respect to BH4 concentration. For BH4 concentrations of 6.93, 6.3, 4.9, 3.5, 1.75, 0.35, 0.07, 0.007 and 0.0007 µM, respectively, which correspond to biopterin ratios of 0.99, 0.9, 0.7, 0.5, 0.25, 0.05, 0.01, 0.001 and 0.0001, the steady state NO production rates were 26.5, 26.1, 25.0, 23.3, 18.4, 6.73, 1.55, 0.14 and 0.013 nM.s−1, respectively and the steady state O2•− production rates were 0.02, 0.2, 0.9, 2.0, 5.0, 13.2, 17.7, 19.1 and 19.29 nM.s−1, respectively. We also ran the simulations by changing the rate constant of the reaction between NO and O2•− to 1010 M−1s−1. The maximum percentage change in the results of NO and superoxide production rates were less than 2 % using the rate constant of 1010 M−1s−1 for the reaction between NO and O2•−.

Figure 3. [BH4]/[TBP] and [BH4] dependent NO and O2•− production rate by eNOS.

The biopterin ratio ([BH4]/[TBP]) was varied from 0.99, 0.9, 0.7, 0.5, 0.25 and 0.05. Panel A, and B represents the time dependent profiles of NO production rate, and the O2•− production rates, respectively with respect to [BH4]/[TBP] ratio. Panel C represents the steady state production rates of NO and O2•− with respect to concentration of BH4. The concentration of total biopterin ([TBP]) was set at a constant value of 7 µM for all the different biopterin ratios simulated. The concentrations of L-Arginine, O2, SOD, CO2 and eNOS were set at constant values of 100µM, 140µM, 10 µM, 1.1 mM and 0.097 µM, respectively for all the cases simulated.

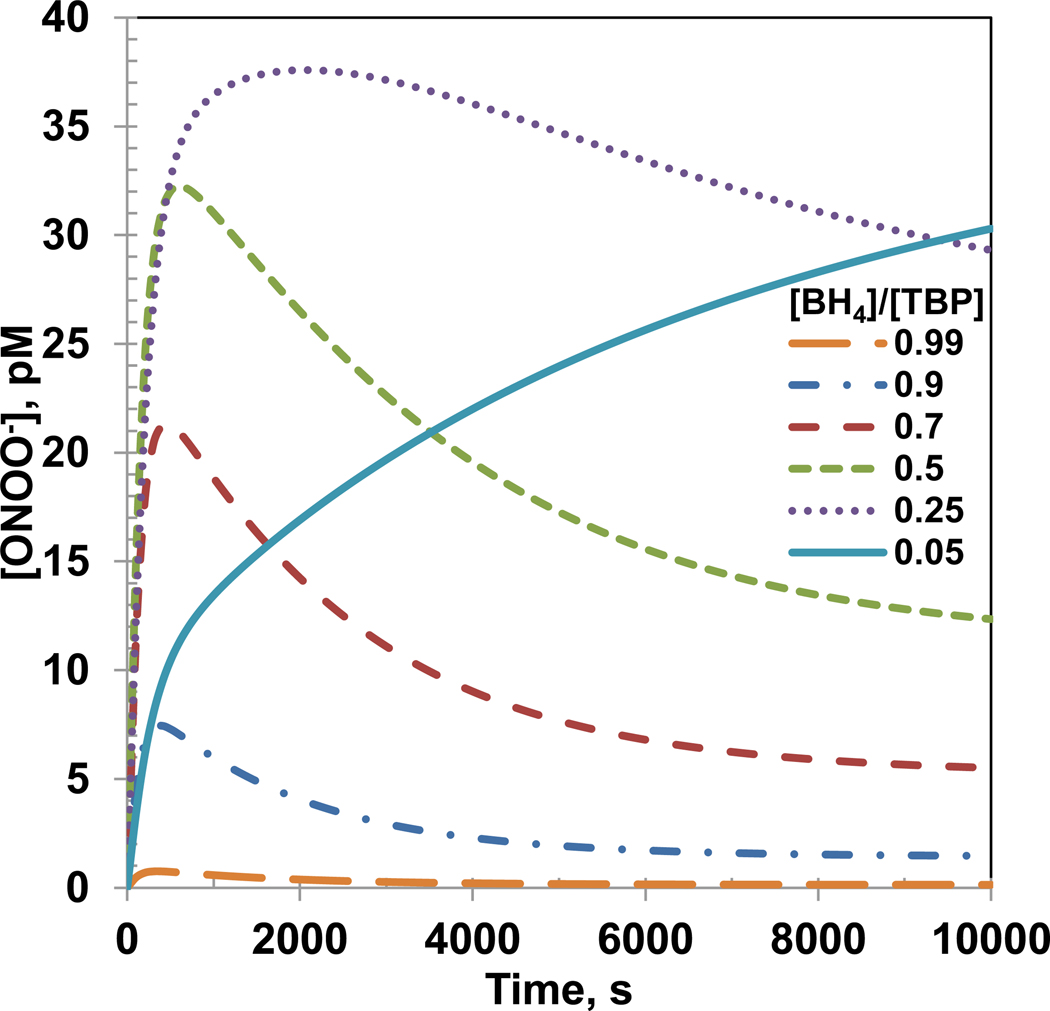

A reduction in [BH4]/[TBP] ratio increases the peroxynitrite concentration

Figure 4 shows the time dependent ONOO− concentration profiles for simulation of varying [BH4]/[TBP] ratio in the previous sub-section. The ONOO− concentrations reached a peak value within 3000 s and the peak values increased as the [BH4]/[TBP] ratio decreased except for [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.05. For [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.05, the ONOO− concentration increased slowly but reached a higher value than all [BH4]/[TBP] ratios at 10000 s. A possible reason for this may be a higher production of O2•− and a lower but increasing production of NO for [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.05. The maximum ONOO− concentrations were 0.7, 7.3, 21.0, 32.2, 38.0 and 39.0 pM for [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.99, 0.9, 0.7, 0.5, 0.25 and 0.05, respectively. Furthermore, the time required to achieve the maximum ONOO− concentration decreased with increasing [BH4]/[TBP] ratio. The steady state ONOO− concentrations were 0.13, 1.4, 5.2, 11.2, 25.3 and 39.0 pM for [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.99, 0.9, 0.7, 0.5, 0.25 and 0.05, respectively.

Figure 4. Peroxynitrite concentration profile for [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.99, 0.9, 0.7, 0.5, 0.25 and 0.05.

The peroxynitrite generation was only from the eNOS produced NO and O2•−. The concentrations of total biopterin ([TBP]), L-Arginine, O2, SOD, CO2 and eNOS were 7 µM, 100µM, 140µM, 10 µM, 1.1 mM and 0.097 µM, respectively.

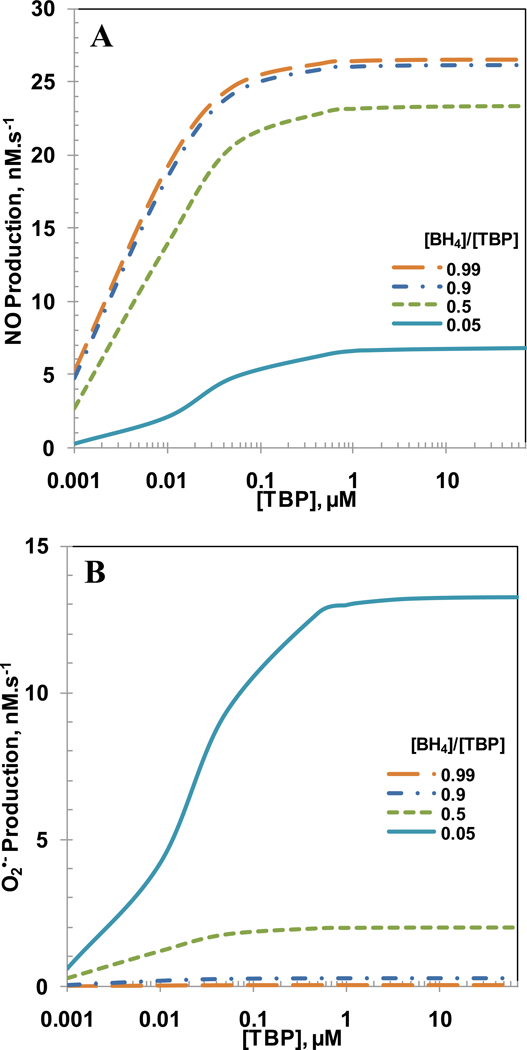

Total biopterin concentration above 1.5 µM have no effect on NO and O2•− production for a constant [BH4]/[TBP] ratio

It is known that BH4 supplementation increases the total biopterin levels ([TBP]) in endothelial cells [23]. Studies investigating the effects of BH4 supplementation on restoration of endothelial function have showed mixed results; in some cases endothelial dysfunction improved [19, 20, 22, 58] while in others endothelial dysfunction remained unchanged or deteriorated [18, 22, 23]. These studies indicate that there may be a possible correlation among BH4 supplementation, total biopterin levels and oxidation of BH4 by oxidizing agents such as O2•−, ONOO− and O2. It is thus important to understand the effect of total biopterin concentration on the NO and O2•− production rates. To understand how total biopterin concentrations affect the NO and O2•− production rates, we varied the total biopterin concentration from 0–70 µM for [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.99, 0.9, 0.5 and 0.05. The concentrations of eNOS, L-Arginine, O2, CO2 and SOD were 0.097 µM, 100 µM, 140 µM, 1.1 mM and 10 µM respectively. As seen in Figure 5A and B, the NO and O2•− production rates increased rapidly with increasing total biopterin concentration and remained constant above total biopterin concentration of 1.5 µM for all ratios. The NO and O2•− production rates dependence on [BH4]/[TBP] ratio showed that the maximum NO production was achieved at [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.99 and the maximum O2•− production was achieved at [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.05. For [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.99, 0.9, 0.5 and 0.05 µM and at total biopterin concentration of 1.5 µM, the steady state NO production rates were 26.451, 26.077, 23.161 and 6.675 nM.s−1, respectively and the steady state O2•− production rates were 0.022, 0.241, 1.969 and 13.069 nM.s−1, respectively.

Figure 5. Effect of total biopterin concentration.

Panel A and B show the eNOS related NO and O2•− production rates, respectively for [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.99, 0.9, 0.5 and 0.05. The concentrations of L-Arginine, O2, SOD, CO2 and eNOS were 100µM, 140µM, 10 µM, 1.1 mM and 0.097 µM, respectively.

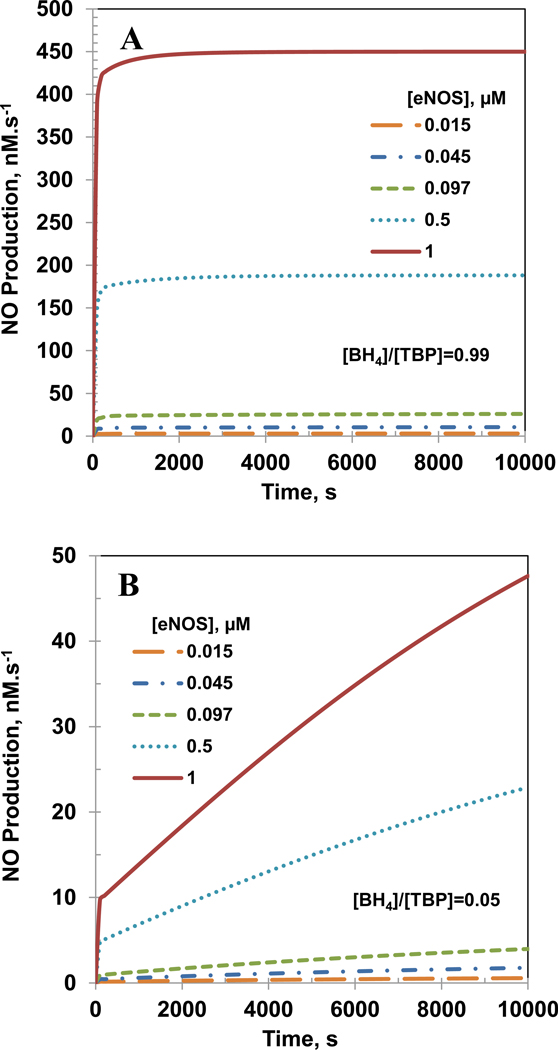

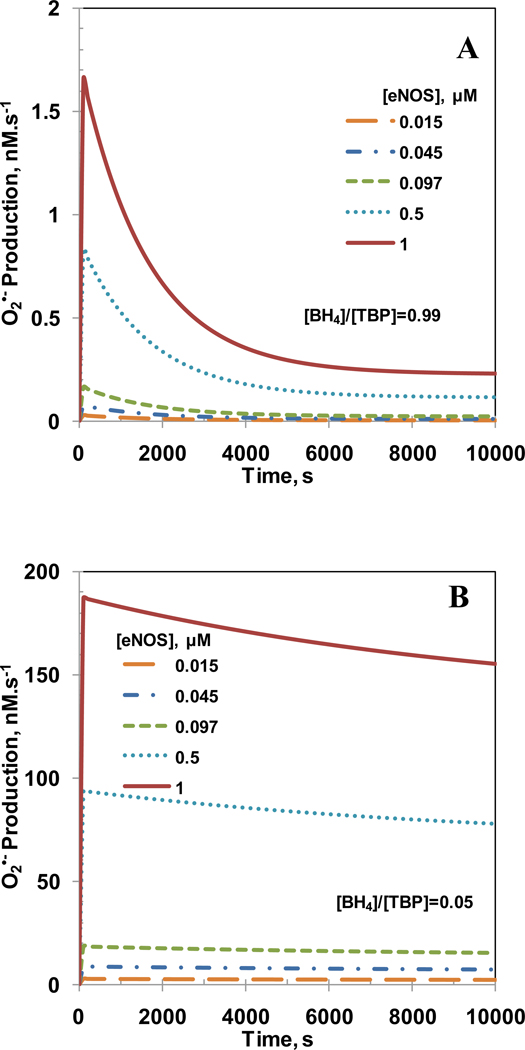

Effect of eNOS concentration on NO and O2•− production rates

Intracellular eNOS concentration range of 0.007–0.097 µM has been reported for endothelial cells as shown in Table 2. It has also been reported that eNOS expression and concentration is significantly elevated under oxidative stress conditions [12, 18, 23, 25]. Figures 6 and 7 show the effect of eNOS concentration on NO and O2•− production rates, respectively for [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.99 (Panel A) and 0.05 (Panel B). The concentrations of total biopterin, L-Arginine, O2, SOD and CO2 were 7 µM, 100 µM, 140 µM, 10 µM and 1.1 mM, respectively. Increased eNOS concentration led to increased production of both NO and O2•− for [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.99 and 0.05. However, the increase in steady state production of NO with eNOS concentration was higher for [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.99 as compared to 0.05, whereas for O2•− the increase in steady state production was higher at the ratio of 0.05.

Figure 6. Effect of eNOS concentration on the NO production rate.

Panel A and B show the effect the NO production rates for biopterin ratio ([BH4]/[TBP]) of 0.99 and 0.05, respectively. The concentrations of total biopterin ([TBP]), L-Arginine, O2, SOD, and CO2 were 7 µM, 100µM, 140µM, 10 µM, and 1.1 mM, respectively.

Figure 7. Effect of eNOS concentration on the O2•− production rate.

Panel A and B show the effect the O2•− production rates for biopterin ratio ([BH4]/[TBP]) of 0.99 and 0.05, respectively. The concentrations of total biopterin ([TBP]), L-Arginine, O2, SOD, and CO2 were 7 µM, 100µM, 140µM, 10 µM, and 1.1 mM, respectively.

For [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.99, the NO production rates were 3.0, 10.6, 26.0, 188.1 and 450.0 nM.s−1 for eNOS concentrations of 0.015, 0.045, 0.097, 0.5 and 1 µM, respectively at 10,000 s. The O2•− production rates were 0.003, 0.010, 0.022, 0.115 and 0.230 nM.s−1 for eNOS concentrations of 0.015, 0.045, 0.097, 0.5 and 1 µM, respectively at 10,000 s. The steady state NO production rates were 3.15, 11.0, 26.5, 188.1 and 450 nM.s−1 while the steady state O2•− production rates were 0.004, 0.01, 0.02, 0.11 and 0.23 nM.s−1 for eNOS concentrations of 0.015, 0.045, 0.097, 0.5 and 1 µM, respectively.

For [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.05, the NO production rates were 0.6, 1.8, 4.0, 23.0 and 48.0 nM.s−1, for eNOS concentrations of 0.015, 0.045, 0.097, 0.5 and 1 µM, respectively at 10,000 s. The O2•− production rates were 2.3, 7.0, 15.1, 78.0 and 156.0 nM.s−1, respectively at 10,000 s. The steady state NO production rates were 0.9, 2.95, 6.73, 37.6 and 77.2 nM.s−1 while the steady state O2•− production rates were 2.1, 6.1, 13.2, 68.1 and 136.0 nM.s−1 for eNOS concentrations of 0.015, 0.045, 0.097, 0.5 and 1 µM, respectively.

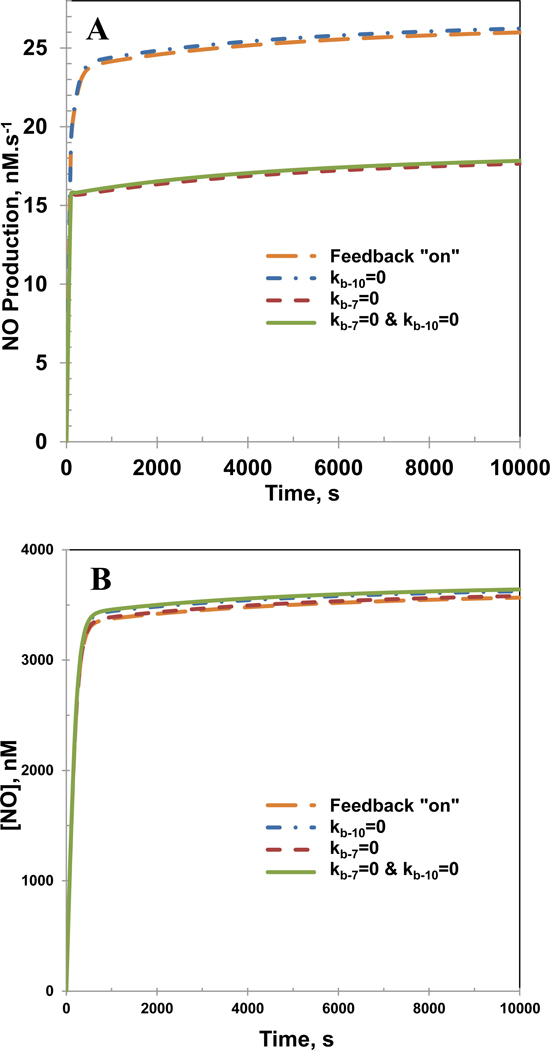

Impact of feedback inhibition on NO production rate and concentration

The reaction schematic (Figure 2A) shows that the competitive binding of NO to eNOS based ferric or ferrous heme. The ferric heme NO complex (Eb5) dissociates in a reversible manner to form NO with the enzyme reverting back to its co-factor bound native state (E). Furthermore, the ferric heme NO complex (Eb5) can be reduced to ferrous heme NO complex (Eb6). This complex also reversibly dissociates to form NO and ferrous heme (Eb7). The backward reaction in these reactions involves consumption of NO. We investigated the effect of the feedback inhibition on the NO production rates and concentration by shutting down (equal to 0) either or both rate constants kb−7 and kb−10.

Figure 8A and B shows the NO production rates and NO concentration, respectively in the presence and absence of the feedback inhibition. While there were no significant changes in the NO concentration profiles, the NO production rates were affected by the feedback inhibition process for the reactions involving the ferric heme NO complex (Eb5), NO and the co-factor bound ferric heme (E). Upon shutting down the backward reaction involving co-factor bound ferric heme (E) and NO, the NO production rate drops from 25 nM.s−1 to 15 nM.s−1. The O2•− production rates and concentrations remain unaffected by the feedback inhibition process (results not shown).

Figure 8. Effects of feedback inhibition pathways for consumption of NO.

Panel A shows the production rate of NO and Panel B shows the temporal NO concentration profiles. The concentrations of total biopterin ([TBP]), L-Arginine, O2, SOD, CO2 and eNOS were 7 µM, 100µM, 140µM, 10 µM, 1.1 mM and 0.097 µM, respectively. The biopterin ratio [BH4]/[TBP] was 0.99.

Effect of glutathione concentration on eNOS based NO and O2•− production

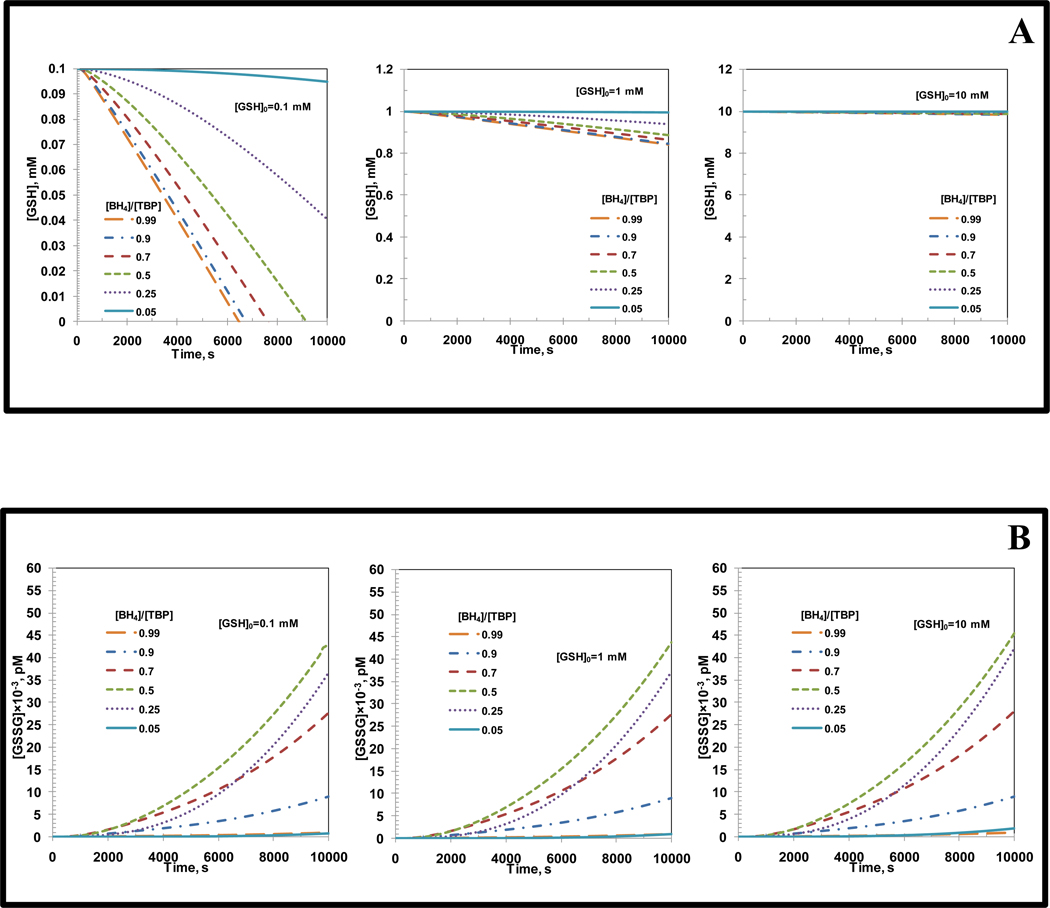

Another important constituent, which is present in mM concentration within endothelial cells is the thiol glutathione (GSH). GSH reacts with ONOO− and N2O3 to form nitroso-glutathione (GSNO) [59]. GSH also forms oxidized glutathione (GSSG) by its reaction with peroxynitrite [59, 60]. GSNO reacts with O2•− to from NO [59]. GSSG can be reduced back to GSH by glutathione reductase [59]. The kinetics of these reactions were incorporated into the current model separately from the earlier analysis along with the mass conservation of all the thiol species. GSH concentrations used were 0.1, 1 and 10 mM. The concentrations of total biopterin ([TBP]), L-Arginine, O2, SOD, CO2, and eNOS were 7 µM, 100 µM, 140 µM, 10 µM, 1.1 mM, and 0.097 µM, respectively. The temporal change in NO and O2•− production rates and GSH and GSSG concentrations were obtained with respect to [BH4]/[TBP] ratio for each of the different initial GSH concentrations ([GSH]0). For all three initial GSH concentrations ([GSH]0), the NO and O2•− production rates were affected less than 1% from those observed in the absence of GSH (results not shown but similar to Figure 3A and B).

The temporal change in GSH concentration with respect to [BH4]/[TBP] ratios and for different initial GSH concentrations ([GSH]0) are shown in Figure 9A. The figures on the left, centre and right in Figure 9A represent [GSH]0 values of 0.1, 1 and 10 mM, respectively. For all the different initial GSH concentrations, the GSH concentration was found to reduce with time for all [BH4]/[TBP] ratios. For initial GSH concentration of 0.1 mM, the GSH concentration at 10,000 s reduced to zero for [BH4]/[TBP] ratios of 0.99, 0.9, 0.7 and 0.5. For [BH4]/[TBP] ratios of 0.25 and 0.05 they were 0.04 and 0.09 mM, respectively. For initial GSH concentration of 1 mM, the GSH concentration at 10,000 s was between 0.85 to 0.9 mM for all [BH4]/[TBP] ratios. For initial GSH concentration of 10 mM, the GSH concentration at 10,000 s was 9.9 mM for all [BH4]/[TBP] ratios.

Figure 9. Effect of incorporation of GSH in the eNOS biochemical pathway.

Panel A shows the temporal variation in the GSH concentration for biopterin ratios of 0.99, 0.9, 0.7, 0.5, 0.25 and 0.05, respectively at initial GSH concentrations ([GSH]0) of 0.1 mM (left), 1 mM (center) and 10 mM (right), respectively. Panel B shows the temporal variation in the GSSG concentration for biopterin ratios of 0.99, 0.9, 0.7, 0.5, 0.25 and 0.05, respectively at initial GSH concentrations ([GSH]0) of 0.1 mM (left), 1 mM (center) and 10 mM (right), respectively. The concentrations of total biopterin ([TBP]), L-Arginine, O2, SOD, CO2, and eNOS were 7 µM, 100µM, 140µM, 10 µM, 1.1 mM and 0.097 µM, respectively.

The temporal change in GSSG concentration for different [BH4]/[TBP] ratios and for different initial GSH concentrations are shown in Figure 9B. The figures on the left, centre and right in Figure 9B represent initial GSH concentrations ([GSH]0) of 0.1, 1 and 10 mM, respectively. For any given initial GSH concentration, the GSSG concentration was found to increase with time. and independent of initial GSH concentration ([GSH]0). For initial GSH concentration of 0.1, 1 and 10 mM, the GSSG concentration at 10,000 s corresponding to [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.99, 0.9, 0.7, 0.5, 0.25 and 0.05 were 0.88×10−3, 8.9×10−3, 27.617×10−3, 43.44×10−3, 36.7×10−3 and 0.82×10−3 pM, respectively.

Discussion

In this study, we developed a computational model for eNOS biochemical pathways for the production of NO and O2•− to understand the eNOS uncoupling and related endothelial dysfunction mechanism. We analyzed the effects of [BH4]/[TBP] ratio, total biopterin, eNOS concentrations and feedback inhibition of NO consumption on NO and O2•− production.

eNOS uncoupling, endothelial cell dysfunction and the importance of [BH4]/[TBP] ratio for the NO and O2•− production rates

Endothelial dysfunction is usually associated with increased oxidative stress in the endothelial region [18, 22–24, 40, 61]. The increased oxidative stress promotes production of more O2•−, which can react with the eNOS generated NO to produce ONOO− [3, 18, 19, 61]. Together, both O2•− and ONOO− aid in the oxidation of the eNOS co-factor BH4 into BH2 [3, 18, 23–25]. BH2 is known to competitively bind with eNOS and increases endothelial O2•− production by uncoupling of eNOS, which also reduces NO production levels [4, 18, 23, 25]. Several studies were performed for analyzing the effect of absolute BH4 levels as well as the biopterin ratio on the extent of eNOS uncoupling [4, 23–25]. However most of these studies could not ascertain accurately whether absolute BH4/biopterin levels or biopterin ratio was more important for controlling eNOS uncoupling. One of these experimental studies [23] also emphasized the need for developing a comprehensive computational model, which could define the boundary conditions associated with BH4 and BH2 levels on the extent of eNOS uncoupling. The current study has been able to achieve these objectives.

There is question regarding which one from the biopterin ratio ([BH4]/[TBP] or BH4:BH2) or absolute level of BH4 is important for the extent of eNOS uncoupling [12, 18, 23, 25]. In this study, the biopterin ratio is expressed as [BH4]/[TBP]. In this notation, a high or low [BH4]/[TBP] ratio indicates that a majority of the biopterin is in the reduced form BH4, or in the oxidized forms BH3 and BH2, respectively. We predicted that NO and O2•− production rates were independent of total biopterin at concentrations above 1.5 µM for a given [BH4]/[TBP] ratio (see Figure 5). With a decreasing [BH4]/[TBP] ratio from 0.99 to 0.05, we predicted that the NO production rate decreased 4 fold and the O2•− production rates increased 594 fold. The increase in O2•− production is more noticeable because of the fact that the primary function of eNOS is to produce NO. Thus, these results indicate that at total biopterin concentration above 1.5 µM, the extent of eNOS uncoupling is only dependent on the [BH4]/[TBP] ratio. At total biopterin concentration above 1.5 µM, supplementation of BH4 can increase eNOS based NO production and reduce eNOS based O2•− production only if the ratio of BH4 to TBP increases.

These model predictions can explain some of the experimental observations. The NO production rate increases with BH4 concentration but is independent of BH4 concentration beyond 2 µM for NO production in the in vitro study of bovine eNOS supplemented by BH4 [4]. Crabtree et al. [23] measured NO and O2•− production rates after the supplementation with BH4 and BH2 in high glucose endothelial cells. They reported that the BH4/BH2 ratio reduced from 1:1 to 1:6 for the supplementation of BH4 but did not change for BH2 supplementation in high glucose cells as compared to normal glucose cells. The reason for the reduction in BH4/BH2 ratio was conversion of BH4 to BH2 in high glucose cells. In addition, the NO production rate decrease 40% and O2•− production rate increase 200% in BH4 supplemented high glucose cells. They concluded that the extent of eNOS coupling correlates inversely with the ratio of intracellular BH4 to BH2, but not absolute levels of intracellular BH4.

Using the GTPCH overexpressed (BH4 producing enzyme) normal and diabetic mouse aortas, Alp et al. [25] observed that the total biopterin levels remains constant whereas BH4 levels reduce from 80% to 10% in the diabetic aortas. In addition, the endothelial O2•− production increases 3 fold in the diabetic aortas. Vasquez-Vivar et al. [40] reported that the BH2/total biopterin ratio increases from 0.3 to 0.63 in the aortas of rabbits on normal cholesterol and high cholesterol diet, respectively, resulting in a 1.3 fold reduction in the endothelial dependent relaxation for high cholesterol diet. Alp et al. [24] reported a [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.25 and 0.80 for an ApoE-KO mouse aorta and a GTPCH overexpressed ApoE-KO mouse aorta, respectively. A 2 fold reduction in endothelial O2•− production was observed in GTPCH overexpressed ApoE-KO mouse aorta.

Comparison of predicted NO production rates with experimental results

Several experimental studies have quantified NO production rates from endothelial cells [55, 62–65] in a number of systems and cell sources. In addition, the NO production rates were reported for isolated vessel segments [66] and for purified eNOS in in vitro systems [4]. The reported NO production rates in endothelial cell lines are 2.19 pM.s−1 [62], 415 nM.s−1 [63], 0.117 nM.s−1 [64] and 2.97 µM.s−1 [65], respectively based on cell volume of 400 µm3, endothelial layer thickness of 4 µm and endothelial cell eNOS concentration of 0.097 µM. In isolated vessels, the NO production rate of 26.53 µM.s−1 is reported by Lu and Kassab [66]. The predicted NO production rates are either several orders of magnitude higher [65, 66] or lower [62, 64] than the NO production rates in endothelial cells or isolated vessels. Possible reasons for the discrepancy include a contribution of NO from other isoforms of NOS and over-estimation or under-estimation of the endothelial cell size or volume leading to incorrect estimation of total eNOS concentration. As seen from Figure 6A, an increase in eNOS concentration to 1 µM predicts NO production rate of 450 nM.s−1 similar to the reported value of 415 nM.s−1 by Hood et al. [63]. In addition, the NO production rates in purified eNOS [4] is similar to the prediction from the current study. Vasquez-Vivar et al. [4] reported experimental NO production rate of 322.7 nM.s−1 for an eNOS concentration of 0.97 µM, which is similar to the model prediction at 1 µM eNOS concentration.

Comparison of predicted O2•− production rates with experimental results

Quantitative studies for measurement of endothelial cell based O2•− production are limited. Arnal et al. [62] and Potdar and Kavdia [65] reported the O2•− production rates of 0.043 nM.s−1 and 2.425 µM.s−1, respectively from endothelial cell lines. The O2•− production rate reported by Arnal et al. [62], is close to the predicted steady state O2•− production rate of 0.02 nM.s−1 for [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.99. Possible reason for several orders of magnitude higher O2•− production rate reported by Potdar and Kavdia [65] may be NADPH oxidase, mitochondrial electron transport chain as the O2•− sources apart from eNOS. For purified eNOS, Vasquez-Vivar at al [4] measured the maximum O2•− production rate of 217.5 nM.s−1 at eNOS concentration of 0.97 µM, which is similar to the predicted maximum O2•− production rate 184 nM.s−1 for eNOS concentration of 1 µM for [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.05.

Comparison of model prediction to existing computational models

Past kinetic modeling studies for eNOS catalysis focused only on the biochemical pathway involving NO synthesis [41, 42]. These studies consider an excess of the co-factor BH4. The NO production rate predicted by Chen and Popel [41] ranged from 3 to 34 nM.s−1 for the eNOS concentration of 0.008 to 0.097 µM, respectively. For 0.097 µM eNOS concentration with [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.99, the steady state NO production rate was 26.5 nM.s−1 in this study. Vaughn et al. [67] developed a mathematical model to estimate NO production rate by utilizing the experimental data of Malinski et al. [68] for NO release from rabbit aorta endothelium. They reported NO production rate of 5.4×10−12 mol.cm−2.s−1, which is equivalent to 13.5 µM.s−1 for endothelial layer thickness of 4 µm. Thus, the NO production rates from our and Chen and Popel [41] models are significantly lower. The possible reasons for this discrepancy are described in the above Section.

Importance of feedback inhibition

As seen in Figure 8A, the NO production rates were reduced by the feedback inhibition process for the reactions involving the ferric heme NO complex (Eb5), NO and the co-factor bound ferric heme (E). Shutting down the backward reaction involving co-factor bound ferric heme (E) and NO causes the NO production rate to drop from 25 nM.s−1 to 15 nM.s−1. This can be explained by looking at the production and consumption pathways of the complex Eb5. Figure 2A shows that Eb5 can be produced from Eb4 (kb6 [Eb4]) and through combination of NO and E (kb−7 [NO] [E]). On the other hand Eb5 can dissociate to from E and NO (kb7 [Eb5]) and also reduce to ferrous heme NO complex (kb8 [Eb5]). Our analysis revealed that the production rate and consumption rate of Eb5 are exactly balanced throughout the simulated timespan. Thus, the removal of the reversible reaction to generate Eb5 leads to a faster consumption of Eb5 in comparison to its production. Since dissociation of the complex Eb5 is responsible for majority of the NO generated, mitigation in its production rate will eventually reduce the production rate of NO itself. Shutting down the reaction involving NO and the ferrous heme complex (Eb7) did not seem to affect the NO production rate. This is due to the extremely slow dissociation rate of the ferrous heme NO complex (Eb6) as experimentally evidenced by Santolini et al. [42].

In conclusion, a biochemical pathway model for eNOS uncoupling and NO and O2•− production was developed. The model results indicate that the extent of eNOS uncoupling is dependent on the ratio of BH4 to TBP. Supplementation of BH4 can only reduce eNOS uncoupling if the ratio of BH4 to TBP increases. It is envisaged that the results from the current study will help understand the mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction and could also aid in understanding the effect of therapeutics for treatment of endothelial dysfunction.

Incorporation of glutathione into the eNOS biochemical pathway

Incorporation of glutathione (GSH) based kinetics into the pre-existing eNOS biochemical pathway did not cause any significant changes in the NO and O2•− production rates for different [BH4]/[TBP] ratios. The temporal GSH concentration profiles as observed in Figure 9A does not drop significantly with time for initial GSH concentrations ([GSH]0) at the physiologically relevant range (1–10 mM). At concentration below physiological range (0.1 mM), the GSH concentration drops almost to zero at [BH4]/[TBP] ratios of 0.99, 0.9, 0.7 and 0.5 suggesting that glutathione reductase is ineffective in restoration of glutathione levels if there is sufficient production of NO and its oxidation products ONOO− and N2O3.

The concentration of oxidized glutathione (GSSG) formed as a result of reaction between ONOO− and GSH was maximum at [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.5 as observed in Figure 9B. This could be due to the fact that at [BH4]/[TBP] ratio of 0.5, there is sufficient production of NO and O2•− which can counteract the enzymatic reduction of GSSG to GSH by glutathione reductase and oxidation of NO to form N2O3. The GSSG concentration profiles shown below are formed as a result of ONOO− formed from reaction between eNOS based NO and O2•−. Since there are other sources of NO and O2•− apart from eNOS, the GSH and GSSG concentration profiles shown in Figure 9A and B, respectively can be much different under actual physiological conditions. This is certainly worth investigating but is beyond the scope of the current study.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by National Institute of Health grant NIH R01 HL084337.

Appendix A1.1

Description of Biochemical Pathways and Downstream Reactions

The three major pathways viz. 1) biochemical pathway for NO production, 2) biochemical pathway for O2•− production, and 3) downstream reactions involving NO, O2•− and ONOO− are described below. Table 1 shows the nomenclature of the different forms of eNOS and the eNOS substrate complexes.

1) Biochemical pathway for NO production

eNOS catalyzes the reaction involving L-Arginine, O2 and NADPH (all substrates) to generate NO and citrulline [1]. The reaction pathway involves two distinct oxidation reaction cycles [41, 69, 70]. These oxidation reaction cycles are oxidation of L-Arginine to generate NHA and subsequent oxidation of NHA to produce NO and citrulline.

Oxidation of L-Arginine to generate NHA

The resting state of eNOS is E−1 (E−1, eNOS-(FeIII)). The heme (Fe3+), which is in the oxygenase domain, is in the resting state of eNOS [1]. The heme in ferric form has a lower redox potential compared to the flavin containing reductase domain. The binding of BH4 to eNOS (E, eNOS-(FeIII)-BH4) can increase the redox potential of the heme sufficiently to facilitate transfer of electrons from the reductase to the oxygenase domain [1]. Next, L-Arginine binds to eNOS-(FeIII)-BH4 in a reversible manner (Ea1, eNOS-(FeIII)-BH4-Arg) increasing its redox potential significantly [1]. We ignored the flavin reduction in the reductase domain as the rate of electron transfer from NADPH to flavin is very fast when CaM is bound to eNOS [71]. Thereafter, the transfer of electron from the reductase domain reduces the heme in the oxygenase domain to ferrous (Fe2+) form (Ea2, eNOS-(FeII)-BH4-Arg). The reduced heme (Fe2+) then binds with O2 reversibly to form a heme-dioxy intermediate (eNOS-[FeII-O2]-BH4-Arg) that is instantaneously converted into a ferric superoxy complex (eNOS-[FeIII-O2−]-BH4-Arg) [1, 41, 72]. The kinetics of this rapid transition was ignored and both these species were considered the same (Ea3, eNOS-[FeII-O2]-BH4-Arg or eNOS-[FeIII-O2−]-BH4-Arg).

In the ferric superoxy complex (Ea3), the bound BH4 donates an electron to form heme peroxo (II) species (Ea4, eNOS-[FeIII-OOH]-BH3-Arg) [70]. The heme peroxo species Ea4 then protonates resulting in the irreversible scission of the oxygen-oxygen bond to form a ferryl iron with eNOS bound cation radical (Ea5, eNOS-[FeIV-O]-BH3-Arg) [1, 70]. The source of protonation could be arginine itself [1, 13]. The ferryl iron species is highly oxidizing and rapidly oxidizes L-Arginine to NHA and the heme is regenerated back to ferric state (Ea6, eNOS-(FeIII)-BH3-NHA). The NHA and the oxidized biopterin (BH3) are still bound to the enzyme (Ea6). The oxidized biopterin is reduced back to BH4 by an electron from the flavin of the reductase domain of the other eNOS monomer (Eb1) [3, 18, 73] resulting in the formation of N-hydroxyl-L-Arginine enzyme complex (Eb1, eNOS-(FeIII)-BH4-NHA).

Oxidation of NHA to produce NO and citrulline

The heme in the Eb1 is reduced to ferrous form (Eb2, eNOS-(FeII)-BH4-NHA) by electron transfer from the reductase domain. In addition, the Eb1 can reversibly dissociate to generate free NHA and the enzyme is returned to its co-factor bound native state E [41]. The enzyme complex Eb2 can reversibly bind to O2 to form intermediate oxy/superoxy complex Eb3 (Eb3, eNOS-[FeII-O2]-BH4-NHA or eNOS-[FeIII-O2−]-BH4-NHA) similar to the oxidation of L arginine to NHA pathway [1]. In addition, the Eb2 can dissociate to release NHA and form Eb7 (Eb7, eNOS-(FeII)-BH4) [41]. In the Eb3, the bound BH4 donates an electron to form heme peroxo (II) species (Eb4, eNOS-[FeIII-OOH]-BH3-NHA) [73, 74].

The peroxo complex in the Eb4 oxidizes the NHA bound to the enzyme into NHA radical and converts into a hydroperoxy complex that reacts almost immediately with each other in a radical rebound mechanism to produce ferric-NO complex (Eb5, eNOS-(FeIII)-NO-BH4) and citrulline [1, 42]. In a reversible reaction, Eb5 releases bound NO and converts the enzyme in co-factor bound native state (E). The Eb5 is reduced to ferrous-NO complex (Eb6, eNOS-(FeII)-NO-BH4), which can then be oxidized by O2 to form nitrate with the enzyme returned to its co-factor bound native state (E) [42]. The Eb6 also dissociates reversibly to release NO with the enzyme converted into Eb7. This reaction occurs at a much slower rate in comparison to decomposition of Eb5 [42]. The Eb7 can also reversibly react with L-Arginine to generate the Ea2 [41].

2) Biochemical pathway for O2•− production

Oxidized form of biopterin, dihydrobiopterin (BH2), competes with BH4 for the binding to eNOS [4, 23, 75]. The binding of BH4 to eNOS results in the biochemical pathway leading to NO production, whereas the binding of BH2 creates a separate biochemical pathway leading to O2•− production. The first three steps following the binding of BH2 to eNOS are similar to those following BH4 binding to eNOS. The binding of BH2 with the enzyme in resting state (E−1), converts the enzyme to an activated state (Ec1, eNOS-(FeIII)-BH2) [43, 50]. Subsequently, L-Arginine binds reversibly to the enzyme to form the enzyme substrate complex Ec2 (Ec2, eNOS-(FeIII)-BH2-Arg) [44, 50]. The heme in the Ec2 is reduced to form ferrous state complex (Ec3, eNOS-(FeII)-BH2-Arg) by electron transfer from the flavin domain as experimentally evidenced by Presta et al. [50].

The O2 binds reversibly with the enzyme complex Ec3 to form a heme dioxy intermediate complex (Ec4, eNOS-[FeII-O2]-BH2-Arg or eNOS-[FeIII-O2−]-BH2-Arg). Berka et al. [43] showed that the rate of enzyme-oxygen binding is independent of biopterin form using full length eNOS and eNOS oxygenase domain in the presence of L-Arginine. Experimental studies have reported that the Ec4 dissociates to form O2•− and Ec2 [21, 43, 72].

3) Downstream reactions involving NO, O2•− and their reaction product peroxynitrite (ONOO−)

The NO and O2•− produced by eNOS react with each other to form a potent oxidizing agent peroxynitrite (ONOO−) [45]. NO, O2•− and ONOO− participates in several redox reactions that can affect the NO or O2•− production rates. The description of important reactions used in this study follows.

- Auto-oxidation of NO by O2 is represented by the following chemical reaction [65]:

(A1) -

Reaction between NO and O2•− to form ONOO− is shown in equation (A2). The ONOO− formed is in rapid equilibrium with peroxynitrous acid (ONOOH) [60, 65].

(A2) The fraction of total peroxynitrite (ONOO−+ONOOH) present in anion form (ONOO−) is calculated as follows [76]:(A3) The acid dissociation constant (pKper) is 6.75 [65, 77]. The pH value was assumed to be 7.4. The peroxynitrous acid dissociates to form NO3− and •NO2 through the following chemical reactions [60, 65]:(A4) (A5) ONOO− rapidly reacts with CO2 to form approximately 33% •NO2+CO3•− and the remaining as NO3−+CO2 according to the following reaction [60]:(A6) (A7) - NO can react with ONOO− or ONOOH to form NO2− according to the following reaction [78]:

(A8) -

The O2•− can undergo dismutation catalyzed by superoxide dismutase (Eq 9) or can self dismutate (Eq 10) to form H2O2 and O2 in the following manner [60]:

(A9) (A10) The superoxide is in acid base equilibrium with hydroperoxyl (HO2) radical with an acid dissociation constant (pK) of 4.8 [77]. The concentration of hydroperoxyl radical is related to the anion form of superoxide (O2•−) as(A11) - The CO3•− radical formed from the reaction between ONOO− and CO2 can react with NO and O2•− as shown below [60].

(A12) (A13) -

Oxidation of BH4 can occur by O2•−, ONOO− and O2 according to the reactions shown below [20, 22, 79, 80].

(A14) (A15) (A16) BH4 can also be oxidized from radicals formed including •OH, •NO2 and CO3•− from the decomposition of peroxynitrous acid and reaction of ONOO− with CO2 [81].(A17) (A18) (A19) -

The oxidized form of biopterin, BH3, can be oxidized by O2 to form BH2 [79].

(A20)

Appendix A1.2

Based on the Description of Biochemical Pathways and Downstream Reactions in Appendix A1.1 and a closer look at the reaction pathways (Figure 2A and B), the justification for the use of 34 model equations is shown below

The oxidation of L-Arginine to NHA involves the native enzyme (E−1) and eight enzyme substrate complexes (E to Eb1), which results in a total of 9 distinct chemical species.

The oxidation of NHA to produce NO and citrulline involves six enzyme substrate complexes (Eb2 to Eb7) resulting in 6 additional chemical species.

The O2•− production pathway involves the native enzyme (E−1) and four enzyme substrate complexes (Ec1 to Ec4). This adds four distinct chemical species excluding the native enzyme (E−1).

The major reaction products add another five chemical species. These include NHA, NO, citrulline, NO3− and O2•−. The oxidation of L-Arginine produces NHA and the oxidation of NHA produces reaction products NO, citrulline, and NO3−. The O2•− is produced from the O2•− production pathway.

A look at the downstream reaction pathway for reactions involving NO, O2•− and their reaction product peroxynitrite indicates major reaction products of BH3, ONOO−, H2O2, NO2, •OH, •NO2, CO3•−, CO32− and OH−. Amongst these, the first seven participate in other reactions whereas the CO32− and OH− are reaction end-products. These reaction end-products were ignored in the kinetic analysis. This adds another seven chemical species.

One of the key objectives of this model is to estimate the production rates of NO and O2•−, two rate expressions for their production were incorporated.

Furthermore, BH2 binds to the native enzyme (E−1). The concentration of BH2 is variable and was accounted in the kinetic analysis.

On the basis of the above statements, the rate equations can be mathematically represented as follows:

| (A22) |

| (A23) |

| (A24) |

| (A25) |

| (A26) |

| (A27) |

| (A28) |

| (A29) |

| (A30) |

| (A31) |

| (A32) |

| (A33) |

| (A34) |

| (A35) |

| (A36) |

| (A17) |

| (A38) |

| (A39) |

| (A40) |

| (A41) |

| (A42) |

| (A43) |

| (A44) |

| (A45) |

| (A46) |

| (A47) |

| (A48) |

| (A49) |

| (A50) |

| (A51) |

| (A52) |

| (A53) |

| (A54) |

| (A55) |

Equation (A22) to equation (A55) represents the rate equations used in the current model. Table 1 shows the chemical composition of the enzyme (such as E−1 and E) and the enzyme substrate complexes (such as Ec1, Ea1 etc.) associated with the rate equations. The terms [Arg], [eNOS], [NHA] and [Cit] represents the concentration of L-Arginine, eNOS, N-hydroxy L-Arginine and citrulline, respectively. Equation (A32) represents the mass conservation of the enzyme (eNOS) and equation (A48) represents the mass conservation of biopterin.

Incorporation of GSH in the analysis adds another four chemical species into the mathematical model, which are GSH, GSNO, N2O3 and GSSG. Furthermore, due to incorporation of GSH, there are additional reactions which includes reaction between ONOO− and GSH and between GSNO and O2•− to produce NO. Hence equation (A41), equation (A45), equation (A49) and equation (A50) had to be modified during the GSH based analysis to account for these reactions. The modified rate equations for NO, O2•−, ONOO− and NO production are as follows:

| (A56) |

| (A57) |

| (A58) |

| (A59) |

In addition, the total thiol species also had to be conserved. Hence the rate equation for GSSG was in the form of an algebraic equation. Therefore in total, the GSH based analysis led to an addition of three ordinary differential equations and one algebraic equation. They are as follows:

| (A60) |

| (A61) |

| (A62) |

| (A63) |

Equation (A60) to equation (A63) represents the rate equations of the additional species incorporated in the model during the GSH based analysis. Equation (A63) represents the mass conservation of thiols. Vm,GR and Km,GR represents the enzymatic kinetic parameters related to the enzyme glutathione reductase and are shown in Table 3.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Alderton WK, Cooper CE, Knowles RG. Nitric oxide synthases: structure, function and inhibition. Biochem J. 2001;357:593–615. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knowles RG, Moncada S. Nitric oxide synthases in mammals. Biochem J. 1994;298(Pt 2):249–258. doi: 10.1042/bj2980249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forstermann U, Munzel T. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase in vascular disease: from marvel to menace. Circulation. 2006;113:1708–1714. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.602532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vasquez-Vivar J, Martasek P, Whitsett J, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B. The ratio between tetrahydrobiopterin and oxidized tetrahydrobiopterin analogues controls superoxide release from endothelial nitric oxide synthase: an EPR spin trapping study. Biochem J. 2002;362:733–739. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3620733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moncada S, Palmer RM, Higgs EA. Nitric oxide: physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 1991;43:109–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suematsu M, Tamatani T, Delano FA, Miyasaka M, Forrest M, Suzuki H, Schmid-Schonbein GW. Microvascular oxidative stress preceding leukocyte activation elicited by in vivo nitric oxide suppression. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H2410–H2415. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.6.H2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kubes P, Suzuki M, Granger DN. Nitric oxide: an endogenous modulator of leukocyte adhesion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:4651–4655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kashiwagi S, Kajimura M, Yoshimura Y, Suematsu M. Nonendothelial source of nitric oxide in arterioles but not in venules: alternative source revealed in vivo by diaminofluorescein microfluorography. Circ Res. 2002;91:e55–e64. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000047529.26278.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kajimura M, Michel CC. Flow modulates the transport of K+ through the walls of single perfused mesenteric venules in anaesthetised rats. J Physiol. 1999;521(Pt 3):665–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young EW, Watson MW, Srigunapalan S, Wheeler AR, Simmons CA. Technique for real-time measurements of endothelial permeability in a microfluidic membrane chip using laser-induced fluorescence detection. Anal Chem. 82:808–816. doi: 10.1021/ac901560w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehta D, Malik AB. Signaling mechanisms regulating endothelial permeability. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:279–367. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Channon KM. Tetrahydrobiopterin: regulator of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in vascular disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2004;14:323–327. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crane BR, Arvai AS, Ghosh DK, Wu C, Getzoff ED, Stuehr DJ, Tainer JA. Structure of nitric oxide synthase oxygenase dimer with pterin and substrate. Science. 1998;279:2121–2126. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5359.2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bredt DS, Snyder SH. Nitric oxide: a physiologic messenger molecule. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:175–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.001135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei CC, Crane BR, Stuehr DJ. Tetrahydrobiopterin radical enzymology. Chem Rev. 2003;103:2365–2383. doi: 10.1021/cr0204350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei CC, Wang ZQ, Arvai AS, Hemann C, Hille R, Getzoff ED, Stuehr DJ. Structure of tetrahydrobiopterin tunes its electron transfer to the heme-dioxy intermediate in nitric oxide synthase. Biochemistry. 2003;42:1969–1977. doi: 10.1021/bi026898h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hurshman AR, Krebs C, Edmondson DE, Marletta MA. Ability of tetrahydrobiopterin analogues to support catalysis by inducible nitric oxide synthase: formation of a pterin radical is required for enzyme activity. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13287–13303. doi: 10.1021/bi035491p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alp NJ, Channon KM. Regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by tetrahydrobiopterin in vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:413–420. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000110785.96039.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crabtree MJ, Tatham AL, Al-Wakeel Y, Warrick N, Hale AB, Cai S, Channon KM, Alp NJ. Quantitative regulation of intracellular endothelial nitric-oxide synthase (eNOS) coupling by both tetrahydrobiopterin-eNOS stoichiometry and biopterin redox status: insights from cells with tet-regulated GTP cyclohydrolase I expression. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1136–1144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805403200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vasquez-Vivar J. Tetrahydrobiopterin, superoxide, and vascular dysfunction. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:1108–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei CC, Wang ZQ, Wang Q, Meade AL, Hemann C, Hille R, Stuehr DJ. Rapid kinetic studies link tetrahydrobiopterin radical formation to heme-dioxy reduction and arginine hydroxylation in inducible nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:315–319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008441200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vasquez-Vivar J, Kalyanaraman B, Martasek P. The role of tetrahydrobiopterin in superoxide generation from eNOS: enzymology and physiological implications. Free Radic Res. 2003;37:121–127. doi: 10.1080/1071576021000040655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crabtree MJ, Smith CL, Lam G, Goligorsky MS, Gross SS. Ratio of 5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin to 7,8-dihydrobiopterin in endothelial cells determines glucose-elicited changes in NO vs. superoxide production by eNOS. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H1530–H1540. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00823.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alp NJ, McAteer MA, Khoo J, Choudhury RP, Channon KM. Increased endothelial tetrahydrobiopterin synthesis by targeted transgenic GTP-cyclohydrolase I overexpression reduces endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis in ApoE-knockout mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:445–450. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000115637.48689.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alp NJ, Mussa J, Cai S, Guzik T, Jefferson A, Goh N, Rockett KA, Channon KM. Tetrahydrobiopterin-dependent preservation of nitric oxide-mediated endothelial function in diabetes by targeted transgenic GTP-cyclohydrolase I overexpression. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:725–735. doi: 10.1172/JCI17786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li L, Chen W, Rezvan A, Jo H, Harrison DG. Tetrahydrobiopterin Deficiency and Nitric Oxide Synthase Uncoupling Contribute to Atherosclerosis Induced by Disturbed Flow. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.226456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsutsui M, Milstien S, Katusic ZS. Effect of tetrahydrobiopterin on endothelial function in canine middle cerebral arteries. Circ Res. 1996;79:336–342. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.2.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hattori Y, Hattori S, Wang X, Satoh H, Nakanishi N, Kasai K. Oral administration of tetrahydrobiopterin slows the progression of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:865–870. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000258946.55438.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sawabe K, Suetake Y, Nakanishi N, Wakasugi KO, Hasegawa H. Cellular accumulation of tetrahydrobiopterin following its administration is mediated by two different processes; direct uptake and indirect uptake mediated by a methotrexate-sensitive process. Mol Genet Metab. 2005;86 Suppl 1:S133–S138. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.An J, Du J, Wei N, Xu H, Pritchard KA, Jr, Shi Y. Role of tetrahydrobiopterin in resistance to myocardial ischemia in Brown Norway and Dahl S rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1783–H1791. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00364.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higashi Y, Sasaki S, Nakagawa K, Fukuda Y, Matsuura H, Oshima T, Chayama K. Tetrahydrobiopterin enhances forearm vascular response to acetylcholine in both normotensive and hypertensive individuals. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15:326–332. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(01)02317-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Setoguchi S, Hirooka Y, Eshima K, Shimokawa H, Takeshita A. Tetrahydrobiopterin improves impaired endothelium-dependent forearm vasodilation in patients with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2002;39:363–368. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200203000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stroes E, Kastelein J, Cosentino F, Erkelens W, Wever R, Koomans H, Luscher T, Rabelink T. Tetrahydrobiopterin restores endothelial function in hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:41–46. doi: 10.1172/JCI119131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heitzer T, Krohn K, Albers S, Meinertz T. Tetrahydrobiopterin improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation by increasing nitric oxide activity in patients with Type II diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2000;43:1435–1438. doi: 10.1007/s001250051551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maier W, Cosentino F, Lutolf RB, Fleisch M, Seiler C, Hess OM, Meier B, Luscher TF. Tetrahydrobiopterin improves endothelial function in patients with coronary artery disease. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2000;35:173–178. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200002000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fukuda Y, Teragawa H, Matsuda K, Yamagata T, Matsuura H, Chayama K. Tetrahydrobiopterin restores endothelial function of coronary arteries in patients with hypercholesterolaemia. Heart. 2002;87:264–269. doi: 10.1136/heart.87.3.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kinoshita H, Katusic ZS. Exogenous tetrahydrobiopterin causes endothelium-dependent contractions in isolated canine basilar artery. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H738–H743. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.2.H738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laursen JB, Somers M, Kurz S, McCann L, Warnholtz A, Freeman BA, Tarpey M, Fukai T, Harrison DG. Endothelial regulation of vasomotion in apoE-deficient mice: implications for interactions between peroxynitrite and tetrahydrobiopterin. Circulation. 2001;103:1282–1288. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.9.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tiefenbacher CP, Bleeke T, Vahl C, Amann K, Vogt A, Kubler W. Endothelial dysfunction of coronary resistance arteries is improved by tetrahydrobiopterin in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2000;102:2172–2179. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.18.2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vasquez-Vivar J, Duquaine D, Whitsett J, Kalyanaraman B, Rajagopalan S. Altered tetrahydrobiopterin metabolism in atherosclerosis: implications for use of oxidized tetrahydrobiopterin analogues and thiol antioxidants. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1655–1661. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000029122.79665.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen K, Popel AS. Theoretical analysis of biochemical pathways of nitric oxide release from vascular endothelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:668–680. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santolini J, Meade AL, Stuehr DJ. Differences in three kinetic parameters underpin the unique catalytic profiles of nitric-oxide synthases I, II, and III. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48887–48898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108666200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berka V, Yeh HC, Gao D, Kiran F, Tsai AL. Redox function of tetrahydrobiopterin and effect of L-arginine on oxygen binding in endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Biochemistry. 2004;43:13137–13148. doi: 10.1021/bi049026j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berka V, Tsai AL. Characterization of interactions among the heme center, tetrahydrobiopterin, and L-arginine binding sites of ferric eNOS using imidazole, cyanide, and nitric oxide as probes. Biochemistry. 2000;39:9373–9383. doi: 10.1021/bi992769y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beckman JS, Koppenol WH. Nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite: the good, the bad, and ugly. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C1424–C1437. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.5.C1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Figueroa XF, Martinez AD, Gonzalez DR, Jara PI, Ayala S, Boric MP. In vivo assessment of microvascular nitric oxide production and its relation with blood flow. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H1222–H1231. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.3.H1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pollock JS, Forstermann U, Mitchell JA, Warner TD, Schmidt HH, Nakane M, Murad F. Purification and characterization of particulate endothelium-derived relaxing factor synthase from cultured and native bovine aortic endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:10480–10484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]