INTRODUCTION

The first human deaths due to air pollution were recorded in the mid-20th century. There were 6,000 cases of illness recorded in Donora, Pennsylvania, in 1948 and 20,000 in London in 1952; 15 and 4,000 cases of death, respectively, were allegedly ascribed to air pollution. Since then, many countries have adopted standards of air quality in order to protect environmental and human health, although the quality of the air in some industrialized countries remains worrying. Emerging countries in the Far East and South America are also cause for concern because of the growth in the population, industrialization and transport (1).

The WHO World Health Report 2002 estimated that air pollutants, particularly PM10, are associated with a mortality rate of 5% for cancer of the respiratory system, 2% for cardiovascular diseases and about 1% for respiratory tract infections. These estimates consider the mortality but not the morbidity rate, which would increase proportionally the number of cases of these pathologies, despite the difficulty in evaluation (2).

ENVIRONMENTAL POLLUTANTS

According to the Italian Presidential Decree no. 203 dated May 24th 1998, air pollution is defined as “any modification to the normal composition or to the physical state of the air, due to the presence of one or more substances in such quantities and characteristics as to alter its healthiness and the normal environmental conditions; this contamination can be directly or indirectly dangerous for human health and could jeopardize recreational and normal activities performed in the environment. Moreover, this could seriously affect biological resources, the ecosystem, and public and private tangible assets”.

The thus-defined pollutants, which can be in gaseous, liquid or solid form, are commonly classified as either primary or secondary. Primary pollutants are released into the atmosphere directly by nature or as a consequence of human activity. Many of these pollutants, which have an elevated reactivity, either intrinsic or sunlight-induced, can combine easily or react with natural substances in the atmosphere, causing secondary pollutants.

The main pollutants derive from:

the combustion process in car engines, domestic heating and industrial equipment;

wear and tear and the dispersion of materials, e.g. the road surface and car tires;

certain manufacturing processes.

Primary pollutants, which include nitrogen monoxide (NO), carbon monoxide (CO), sulphur dioxide (SO2) and volatile organic compounds, originate from the above sources.

Secondary pollutants include nitrogen dioxide (NO2), ozone (O3), sulphuric acid (H2SO4), aldehydes, ketones, peroxides and particulate matter (PM) (3).

Nitrogen oxides

Nitrogen oxides are highly reactive substances, and most toxicological and epidemiological studies have focused on NO2. The main anthropogenic source of NO2 is fossil combustion, especially in motor vehicles and industrial processes. NO2 concentrations have been seen to peak in the morning and late afternoon, in conjunction with rush-hour traffic. Other natural sources of NO2 and NO are bacterial metabolism, volcanic emissions and photolytic reactions (4–6).

These pollutants have a toxic effect on the respiratory, immune and hemocoagulative systems since they are able to combine with haemoglobin, thereby reducing the activity of the immune system (7, 8).

Carbon monoxide (CO)

Carbon monoxide is a product of the incomplete combustion of carbon-containing fuels and cigarette smoking (9, 10).

CO is a ubiquitous, odourless and colourless gas, which binds to hemoglobin with an affinity 250 times that of oxygen. CO binding to hemoglobin, changing its conformation, causes a reduced release of O2 at the tissue level and cellular hypoxia. In addition, CO binds to numerous other cellular (or extravascular) proteins, e.g. cytochrome P450, catalase, peroxidases and myoglobin, interfering with mitochondrial respiration.

At present, measuring CO concentration in the air serves more as an indicator of combustion-derived pollution than one of toxicity. Only in a few specific cases, such as in poorly ventilated areas, can CO reach a high enough concentration to lead to intoxication (poisoning) (11).

Sulphurous anhydride/sulphur dioxide

SO2 is a soluble gas with a pungent smell and taste that irritates the eyes and mucous membranes. Because of its strong affinity for water, most SO2 is retained in the rhinopharynx, and only a small quantity reaches the deepest areas. SO2 can cause bronchoconstriction and phlogosis of the upper airway in subjects occupationally exposed to high SO2 concentrations (12).

One of the main sources of SO2 is combustion, especially in diesel engines. High levels of SO2 have been associated with numerous air pollution catastrophes in the 20th century; morbidity and mortality in these episodes are closely related to its role in the formation of particulate matter (sulphates).

Ozone

Ozone is a highly-reactive gas, and is naturally present in the stratosphere, where it prevents high-energy UV radiation from penetrating the atmosphere. Yet in the troposphere, where ozone should not actually be present, it is formed by the action of solar UV radiation on nitrogen oxides and on hydrocarbons (photochemical smog), both of which are released by motor vehicles and industrial processes. This is why the toxic effects of ozone peak in the late-afternoon hours, especially on sunny days. The toxicity of O3 derives from its tendency to oxidize tissues. For instance, ozone can cause premature ageing of the parenchyma and the epithelial structure, and hence reduced resistance to pathogenic agents (13–15).

Particulate matter

Airborne PM consists of a mixture of liquid and solid air-suspended particles, which are released straight into the atmosphere or after the transformation of gas into particles from natural or human-induced processes (16–19).

PM can be classified according to:

dimensions, into dust, smoke, smog or soot and fog;

origin, into primary PM (if emitted into the atmosphere) and secondary PM (if resulting from the physiochemical transformation of gases);

source, into natural or anthropogenic (Tab. I)

TABLE I. - SOURCES OF FINE PARTICULATE (Marconi A, Ann Ist Super Sanità 2003; 39 (3): 329–42, modified).

| Natural |

|---|

| Sea spray |

| Mineral dust carried by the wind |

| Volcanic emissions (directly emitted particles and those produced by the reaction of gaseous compounds) |

| Biogenic materials (directly emitted particles and secondary ones resulting from the condensation of organic substances emitted by plants) |

| Smoke resulting from forest fires or burning vegetable matter |

| Products of natural gas particle conversion reactions (e.g. sulphates generated by reduced sulphur emitted by ocean surfaces and reactions with marsh gases) |

| Anthropogenic |

|---|

| Particles emitted from industrial processes, combustion processes, means of transport, construction work (ash, smoke, road dust, etc.) |

| Products of the conversion of gases generated by the combustion of fossil materials |

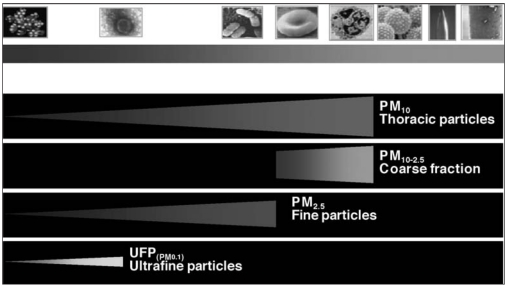

The most important parameter for defining the toxicity of PM is particle diameter. Ultrafine particles, the so-called “Aitken nuclei”, 0.01 µm < UFPs > 0.1 µm in diameter, usually result from the homogeneous nucleation of oversaturated vapors, e.g. the combustion process, forming SO2, NH3 and NOx.

The so-called “fine” particles, 0.1 µm < PM > 2.5 µm in diameter, are the result of the coagulation of UF particles, the physiochemical transformation of gases into particles (also known as heterogenic nucleation) or the condensation of the gas on pre-existing particles in the accumulation fraction rate. In industrialized countries, the most common constituents include sulphates, nitrates, elemental and organic carbon, a variety of metals deriving from combustion processes, and ammonium ions. Sulphates, nitrates and ammonium are basically the result of the transformation of SO2, NO2 and CO from a gaseous to a particle state.

0.1 µm < PMs > 2.5 µm can also include particles of biological origin, e.g. fungal spores, bacteria, pollen grains and endotoxins. Fine particles are generally too small to deposit and too big to agglomerate and coalescence into larger particles, enabling them to remain in the atmosphere for days and cover long distances.

2.5 µm < PMs > 10 µm, the so-called “coarse particles ”, derive from grinding or erosion processes, and include windblown soil. They include elements that are present in the soil or in sea salt, e.g. Si, Al, Ca, Fe, Mn, Na, Sr and K.

Due to their fairly large size, these particles are usually released by the atmosphere and settle in a few hours, and they are commonly found near the source of emission, depending on its height (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

- Classification of particulate matter according to its dimensions (Brook RD, et al. Circulation 2004; 109: 2655–71, modified).

EPIDEMIOLOGICAL STUDIES

Many published epidemiological studies link environmental air pollution to the incidence of human illnesses. Even though many pollutants can cause diseases individually or in combination (e.g. NO2, SO2 and O3), research in the last few years has focused on PM (20–23). The acute and chronic effects of PM10 on human health have been described. There are many epidemiological studies on short-term health effects and outcomes (mortality, hospital admissions, symptoms); they are related to the modification of pollutant concentrations in the short term. There are few studies on chronic effects, and they are based on data (such as total mortality and cardiovascular events) recorded in different geographic areas with different concentrations of air pollutants.

Studies on the acute effects of air pollution

The global result of studies conducted in the U.S.A. and Canada up until 1997 showed that each 10 µg/m3 increase in PM10 was associated with a 1% increase in daily mortality and hospital admissions (24–26).

The European Approach Project (APHEA – 2) (27) has observed 43 million people in 29 European cities for 5 years: the estimated increase in daily all-cause mortality was 0.6% for each 10 µg/m3 increase in PM10. When also considering daily hospitalization for BPCO and cardiovascular events in subjects aged over 65, researchers observed an increased incidence of 1% and 0.5%, respectively, for each 10 µg/m3 increase in PM10.

A similar North American study, the NMMAPS (National Mortality, Morbidity and Air Pollution Studies) (28), which involved 20 cities and more than 50 million people, reported a 0.5% increase in daily all-cause mortality for each 10 µg/m3 increase in PM10.

Two MISA studies have been conducted in Italy: MISA 1 (Meta Analysis of the Italian Studies on the short-term effects of air pollution) produced - for the first time in Italy - a complete estimate of the short-term effects of air pollutants on human health; the MISA 2 study, conducted between 1996 and 2002, considered a larger population (9 million people), and included Southern Italy (29). In conjunction with the increased concentration of air pollutants studied (PM10, CO, NO2), researchers observed an increase in daily all-cause and cardio-respiratory mortality, as well as an increase in hospital admissions due to cardiac and respiratory diseases. The association between the concentration of pollutants and the incidence of illness depends on the type of pollutant and the considered outcome. For daily all-cause mortality, for instance, the increased risk is evident within a few days of the peak in pollution (2 days for PM10, up to 4 days for CO and NO2). The total daily all-cause impact on mortality for gaseous pollutants such as CO and NO2 is between 1.4% and 4.1%; PM10 evaluation is more difficult because of the differences in the estimates of the cities considered (0.1% – 3.3%). It is agreed, however, that restrictive measures for controlling PM10, if applied until 2010, could save 900 lives (1.4%). Some recent studies conducted in Austria, France and Switzerland have indicated PM10 as being responsible for 6% of total deaths, i.e. 40,000 deaths each year, half of which are attributed to urban traffic (30).

Finally, some recent studies conducted in the United States and Europe have shown a high number of hospital admissions due to cardiovascular problems - 0.8% heart failure and 0.7% ischemic heart disease - as a consequence of each 10 µg/m3 increase in PM10. Other studies have reported a higher incidence of hypertension, myocardial ischemia during stress-testing, arrhythmias and stroke in the presence of elevated PM10 levels (31–34).

Chronic effects of pollutants

The Six Cities Study (35) was the first prospective study to demonstrate the long-term negative effects of pollutants on health. Cardiovascular mortality is directly related to pollution, with a RR of mortality of 1.26% among 8,111 patients with 14–16 years of follow-up. The data were confirmed, even after adjustment for age, gender, smoking, body mass index, occupational exposure and diabetes. Of the 1,401 deaths, 646 were due to cardiovascular causes.

The ACS Cancer Prevention II Study (28), involving 500,000 patients living in 50 different countries with a 16-year follow-up, confirmed these data. Each 10 µg/m3 increase in PM2.5 resulted in an increase in daily all-cause, cardiopulmonary and lung cancer mortality of 4%, 6%, and 8%, respectively. PM2.5, sulphuric dioxide, sulphate particles and O3 were the most dangerous pollutants. Lastly, Hoek et al (36) pointed out that exposure to toxic substances may vary from place to place within the same town. Living near a major road was associated with increased cardiopulmonary mortality (RR 1.95).

BIOLOGICAL EFFECTS

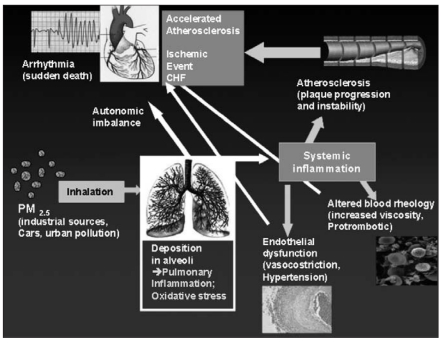

The biological mechanism correlating air pollutants with cardiac diseases are only partially understood. Air pollutants can affect the cardiovascular system directly (within a few hours). Some gaseous pollutants and ultrafine particles go straight into the circulatory system, penetrating the pulmonary epithelium. Other pollutants act indirectly (within several hours or days) via pulmonary oxidative stress, leading to a systemic inflammatory state (17–19).

The potential mechanism of the effects of PM10 on the cardiovascular system is shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

- Possible biological mechanisms linking PM to cardiovascular disease. (Brook, RD et al, Circulation 2004; 109: 2655–71, modified).

Oxidative stress and systemic or pulmonary inflammatory state

Several studies conducted in in vitro animal and cellular models have shown that exposure of lung tissue to PM10 and O3 produces an inflammatory response and that the presence of metal elements enhances the toxic effects by increasing oxidative stress (37–44).

A recent study conducted on rats showed a doubling in reactive oxygen species in hearts and lungs after 2 hours’ exposure to PM2.5 (45).

In addition, exposure to high concentrations of PM2.5 caused an increase in levels of markers of lipid and protein oxidation in human beings (46). Oxidative stress causes the activation of transcription factors, e.g. NFKB and protein-1 activator, which are linked to the production of cytokines, chemokines and other proinflammatory mediators (47). PM2.5 induces apoptosis and necrosis of macrophages and respiratory epithelial cells; it possibly decreases immunitary defenses and increases airway reactivity (48).

Finally, the inflammatory intrapulmonary response is due in part to stimulation by the irritant particles of sensory neurons. They stimulate the release of neuropeptides (e.g. substance P and neurokinin A), which in turn stimulate the production of cytokines, vasodilatation and mucus secretion. Moreover, neuropeptides increase the inflammatory response by acting on epithelial and smooth muscle cells as well as on polymorphonuclear leukocytes, lymphocytes, eosinophils and so on (49–51).

During some recent studies, rats were given 5 mg PM10 intrapharyngeally twice a week; an increase in the production and release of polymorphonuclear leukocytes into the bone marrow was observed three weeks latee (52). In addition, more extensive inflammation was seen in the alveolar macrophages, epithelial cells and airway walls (53). Additional observational studies have confirmed that healthy patients exposed to high PM10 and O3 concentrations produce an inflammatory response. This is confirmed by an increase in B and T cells, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, mast cells, and inflammatory and fibrinogenous mediators (54, 55).

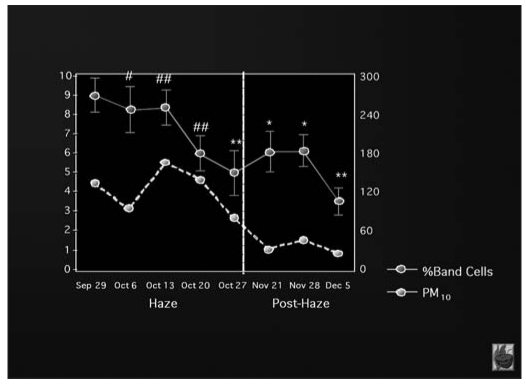

Other studies have shown that air pollution can induce a systemic inflammatory response, regardless of the effects on the lungs: exposure to forest fire smoke (measured as PM10 and SO2) causes the bone marrow to release immature polymorphonucleates cells even if lung function has not been manifestly affected (56) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

- Increase in white blood cells count in relation to PM10 levels (Tan WC et al, Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 161: 1213–7) (modified).

Systemic inflammation and oxidative stress effects on the cardiovascular system

Nearly 10 years ago, Seaton et al (57) put forward the hypothesis that exposure to PM10 could provoke alveolar inflammation, which in turn could lead to the worsening of pre-existing diseases, increased blood coagulability and a high risk of cardiovascular events. Additional studies indicated that exposure to PM10 increases fibrinogen, which is a well-known independent risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke (58–61).

An increased concentration of granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IL-6 and IL-1 was observed in healthy males exposed regularly to air pollutants, giving a high risk for cardiovascular events and mortality (62–65). In the bone marrow, GM-CSF stimulates the differentiation and the release of granulocytes and monocytes as well as their degranulation at a peripheral state. IL-1 stimulates the inflammatory stage through the production of further cytokines and the activation of endothelial cells. IL-6 stimulates the synthesis of C-reactive protein in the liver, i.e. CPR, fibrinogen and thrombopoiesis in the bone marrow (66–68). These three cytokines, especially when combined, are able to promote a systemic inflammatory response with an increase in leukocytes, platelets, and proinflammatory and prothrombotic proteins. They also activate leukocyte and endothelium response, promoting the recruitment and migration of the inflammatory cells into the arterial wall.

High CPR levels have been associated with increased cardiovascular risk. In patients with coronary artery disease, CPR enhances endothelial dysfunction, directly stimulating the production of “foam cells”, the migration of monocytes into the arterial wall, the inhibition of NO-synthase activity, and the expression of adhesion molecules along with prothrombotic factors (69–71).

As a result, air pollution, and the systemic inflammation associated with it, plays an important role in promoting atherosclerosis formation in the long term and acute plaque instability in the short term. A study of hyperlipidemic rabbits exposed to PM revealed a progression of coronary artery disease and high lipid levels after 4 weeks. The degree of plaque formation is linked to the number of alveolar macrophages that phagocytosed PM10 (72).

Many studies correlate atmospheric pollution with vascular tone alterations. One on healthy patients exposed to PM and O3 for two hours showed elevated arterial vasoconstriction. Reduced NO-production and a higher concentration of endothelins have also been observed (73–76).

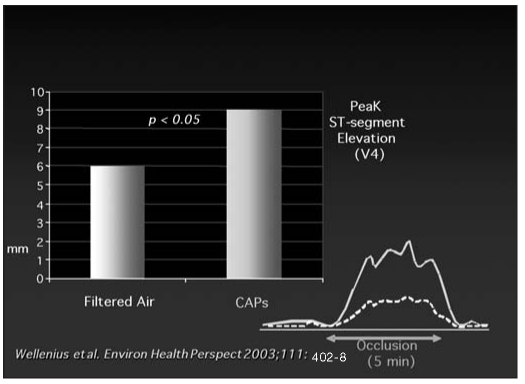

The ULTRA study (Exposure and Risk Assessment of Fine and Ultrafine Particles in Ambient Air) showed that ischemic patients, exposed to PM two days before submaximal exercise, had an increased ST-segment depression during the test. This suggests that air pollution increases susceptibility to myocardial ischemia and infarction (77). The same findings of higher susceptibility to myocardial ischemia were obtained in an experimental study (78) of dogs exposed to concentrated ambient particles (CAP) three or four consecutive times a week for 6 months. They suffered occlusion of the left anterior descending coronary (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

- In dogs, the inhalation of concentrated ambient particles (CAPs) increases susceptibility to myocardial ischemia (Wellenius et al, Environ Health Perspect 2003; 111: 402–8) (modified).

Alterations in sympatho-vagal tone

The increased cardiovascular mortality following exposure to atmospheric pollutants can be explained by alterations in the autonomic nervous system, as shown by heart rate variability (HRV), resting heart rate and blood pressure.

Reduced HRV detected by analysis of time domain (RR intervals) and frequency domain (LF/HF rate) is a predictive factor for increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, especially in patients with severe heart disease (79).

The reduction in HRV linked to exposure to PM10 is an expression of the imbalance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. Patients with a cardioverter defibrillator maintained for three years showed a correlation between the number of discharges and NO2 and CO concentration (80). Increased mortality for threatening arrhythmias is related to PM10 exposure in the week before the event.

This clinical evidence is supported by experiments conducted on animals, for instance increased LF/HF rate in dogs exposed to PM for 6 hours on three consecutive days. Another study reported decreased HRV and increased arrhythmia frequency in a myocardial infarction model (81).

The pathogenetic mechanisms causing the alterations in sympatho-vagal tone remain unclear, however, they could involve activation of pulmonary neural reflex, direct effects on cardiac ion channels and the systemic inflammatory state (82–84). In response to the inflammation caused by atmospheric pollutants, the autonomic nervous system produces neuropeptides and catecholamines, which can alter the regulation of the cardiac autonomic nervous system.

Exposure to PM10 can, in fact, induce a systemic response with an elevated sympathetic systemic tone and higher resting heart rate (0.8 beats/min each 100 µg/m3 increase), leading to HRV reduction and major susceptibility to life-threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Finally, PM10 influence on pulmonary receptors could stimulate the growth of parasympathetic tone and be a predisposing factor for bradyarrhythmias.

CONCLUSIONS

Although the results of observational studies may be influenced by numerous factors, such as the characteristics of the pollutant, the population studied, the methods and some confounding factors, certain conclusions can be drawn.

Exposure to high PM concentrations significantly increases cardiovascular mortality rate and hospital admissions due to pulmonary CV diseases, especially in high-risk patients.

Evidence of such effects on public health has spurred international organizations to review the regulations for PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations, taking place in the United States in 1987 and 1997. The E.U. has established the maximum concentration for PM10, but not for PM2.5, although air sampling and providing the public with information on the pollutant are mandatory. Moreover, action plans for reducing PM10 levels include measures for lowering PM2.5 levels as well.

Table II shows the reference frame for daily and yearly PM10 limits provided for in 2005, along with the range of tolerance values established in previous years. The goals set for 1st January 2010 include reducing the PM10 yearly limit to 20 µg/m3, with a tolerance of 10 µg/m3 which will have to be eliminated by that date; the daily limit is 50 µg/m3, and it is not to be exceeded more than seven times a year. This regulation plays an important role in the introduction of a system for controlling, reducing and managing air pollution.

TABLE II. - LIMIT VALUE OF PM10 PROVIDED BY UE.

| Annual Limit Value (µg/m3) | Date of current Entry | Limit Value/24 h (µg/m3) |

|---|---|---|

| 48.0 | 2000 | 75 |

| 46.4 | 2001 | 70 |

| 44.8 | 2002 | 65 |

| 43.2 | 2003 | 60 |

| 41.6 | 2004 | 55 |

| 40 | 2005 | 50 |

Our study, which will be published in the next issue of this Journal, has shown that air pollution significantly increases the number of hospital admissions due to CV disease, especially HF and CAD. Air pollution should therefore be considered an additional risk factor alongside the traditional ones.

Further studies are required to assess more effective preventive measures for reducing air pollution.

It would also be useful to study pharmacological treatments to protect the endothelium against the inflammatory effect of PM10, especially in high-risk patients with HF, AICD and previous myocardial infarction.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rahaman Q, Nettesheim P, Smith KR, Seth PK, Selkirk J. International conference on environmental and occupational lung disease. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:425–31. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO; 2003. The World Health Report 2002 - Reducing risks, promoting healthy life. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seinfeld JH, Pandis SN. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1998. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: From Air Pollution to Climate Change; pp. 1–1326. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipsett MJ. Oxides of nitrogen and sulphur. In: Sullivan JB, Krieger GR, editors. Clinical Environmental Health and Toxic Exposures. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. pp. 818–32. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spengler J, Schwab M, Ryan PB, et al. Personal exposure to nitrogen dioxide in the Los Angeles Basin. J Air Waste Manage Assoc. 1994;44:39–47. doi: 10.1080/1073161x.1994.10467236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marbury MC, Harlos DP, Samet JM, et al. Indoor residential NO2 concentrations in Albuquerque, New Mexico. JAPCA. 1988;38:392–8. doi: 10.1080/08940630.1988.10466388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith W, Anderson T, Anderson HA, et al. Nitrogen dioxide and carbon monoxide intoxication in an indoor ice arena: Wisconsin, 1992. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1992;41:383–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karlson-Stiber C, Höjer J, Sjöholm Ö, et al. Nitrogen dioxide pneumonitis in ice hockey players. J Intern Med. 1996;239:451–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1996.484820000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hampson NB, Norkool DM. Carbon monoxide poisoning in children riding in the back of pickup trucks. JAMA. 1992;267:538–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagberg M, Kolmodin-Hedman B, Lindahl R, et al. Irritative complaints, carboxyhemoglobin increase and minor ventilatory function changes due to exposure to chain-saw exhaust. Eur J Respir Dis. 1985;66:240–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seger DL, Welch LW. Clinical Environmental Health and Toxic Exposures. In: Sullivan JB, Krieger GR, editors. Carbon monoxide. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. pp. 722–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lipsett MJ. Clinical Environmental Health and Toxic Exposures. In: Sullivan JB, Krieger GR, editors. Ozone. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. pp. 806–18. [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. WHO Regional Publications, European series No. 23. Copenhagen. Denmark: World Health Organization; 1987. Air quality guidelines for Europe. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Environmental Protection Agency. Washington, DC: US Environmental Protection Agency; 1996. Office of Research and Development, National Center for Environmental Assessment. Air Quality Criteria for Ozone and Related Photochemical Oxidants. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lioy PJ, Dyba RV. Tropospheric ozone: the dynamics of human exposure. Toxicol Ind Health. 1989;5:493–504. doi: 10.1177/074823378900500309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daigle CC, Chalupa DC, Gibb FR, et al. Ultrafine particle deposition in humans during rest and exercise. Inhal Toxicol. 2003;15:539–52. doi: 10.1080/08958370304468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brook RD, Franklin B, Cascio W, et al. Air Pollution and Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation. 2004;109:2655–71. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000128587.30041.C8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marconi A. Materiale particellare aerodisperso: definizioni, effetti sanitari, misura e sintesi delle indagini ambientali effettuate a Roma. Ann Ist Super Sanità. 2003;39:329–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oberdorster G, Sharp Z, Atudorei V, et al. Extrapulmonary translocation of ultrafine carbon particles following whole-body inhalation exposure of rats. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2002;65:1531–43. doi: 10.1080/00984100290071658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brunekreef B, Holgate ST. Air pollution and health. Lancet. 2002;360:1233–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11274-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pope CA. Epidemiology of fine particulate air pollution and human health: biologic mechanisms and who’s at risk? Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108:713–23. doi: 10.1289/ehp.108-1637679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brook RD, Brook JR, Rajagopalan S. Air pollution: the “heart” of the problem. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2003;5:32–9. doi: 10.1007/s11906-003-0008-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.HEI Health Review Committee and Scientific Staff. HEI Perspectives. Cambridge, Mass: Health Effects Institute; Apr, 2002. [Accessed April 15, 2004.]. Understanding the health effects of components of the particulate matter mix: progress and next steps. Available at: http://www.healtheffects. org/Pubs/Perspectives-2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pope CA, Burnett RT, Thurston GD, et al. Cardiovascular mortality and long-term exposure to particulate air pollution: epidemiological evidence of general pathophysiological pathways of disease. Circulation. 2004;109:71–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000108927.80044.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pope CA, Burnett RT, Thun MJ, et al. Lung cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. JAMA. 2002;287:1132–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.9.1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dominici F, McDermott A, Daniels D, et al. Boston, Mass: Health Effects Institute; 2003. Mortality among residents of 90 cities. In: Special Report: Revised Analyses of Time-Series Studies of Air Pollution and Health; pp. 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katsouyanni K, Touloumi G, Samoli E, et al. Confounding and effect modification in the short-term effects of ambient particles on total mortality: results from 29 European cities within the APHEA2 Project. Epidemiology. 2001;12:521–31. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200109000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pope CA, Thun MJ, Namboodiri MM, et al. Particulate air pollution as a predictor of mortality in a prospective study of U.S. adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:669–74. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/151.3_Pt_1.669. (pt 1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biggeri A, Bellini P, Terracini B. Metanalisi italiana degli studi sugli effetti a breve termine dell’inquinamento atmosferico. Epidemiol Prev. 2001;25(suppl. 2):1–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Künzli N, Kaiser R, Medina S, Studnika M, Chanel O, Filliger P, Hery M, Horak F, Jr, Puybonnieux, Texier V, Quenel P, Chneider, Eethaler R, Vergnaud JC, Sommer H. Public-health impact of outdoor and traffic-related air pollution: a European assessment. Lancet. 2000;356:795–801. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02653-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burnett RT, Smith-Doiron M, Steib D, et al. Effects of particulate and gaseous air pollution on cardiorespiratory hospitalizations. Arch Environ Health. 1999;54:130–9. doi: 10.1080/00039899909602248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwartz J. Air pollution and hospital admissions for heart disease in eight US counties. Epidemiology. 1999;10:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoek G, Brunekreef B, Fischer P, et al. The association between air pollution and heart failure, arrhythmia, embolism, thrombosis, and other cardiovascular causes of death in a time series study. Epidemiology. 2001;12:355–7. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200105000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morris RD. Airborne particulates and hospital admissions for cardiovascular disease: a quantitative review of the evidence. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109(suppl 4):495–500. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109s4495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dockery DW, Pope CA, Xu X, et al. An association between air pollution and mortality in six US cities. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1753–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312093292401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoek G, Brunekreef B, Goldbohm S, et al. Association between mortality and indicators of traffic-related air pollution in the Netherlands: a cohort study. Lancet. 2002;360:1203–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11280-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelly FJ. Oxidative stress: its role in air pollution and adverse health effects. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60:612–6. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.8.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghio AJ, Kim C, Devlin RB. Concentrated ambient air particles induce mild pulmonary inflammation in healthy human volunteers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:981–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9911115. (3 pt 1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aris RM, Christian D, Hearne PQ, et al. Ozone-induced airway inflammation in human subjects as determined by airway lavage and biopsy. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:1363–72. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.5.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Godleski JJ, Clarke RW, Coull BA, et al. Composition of inhaled urban air particles determines acute pulmonary responses. Ann Occup Hyg. 2002;46(suppl 1):419–24. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Costa DL, Dreher KL. Bioavailable transition metals in particulate matter mediate cardiopulmonary injury in healthy and compromised animal models. Environ Health Perspect. 1997;105(suppl 5):1053–60. doi: 10.1289/ehp.97105s51053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kennedy T, Ghio AJ, Reed W, et al. Copper-dependent inflammation and nuclear factor-kappaB activation by particulate air pollution. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;19:366–78. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.19.3.3042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brain JD, Long NC, Wolfthal SF, et al. Pulmonary toxicity in hamsters of smoke particles from Kuwaiti oil fires. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106:141–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.98106141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li XY, Gilmour PS, Donaldson K, et al. Free radical activity and pro-inflammatory effects of particulate air pollution (PM10) in vivo and in vitro. Thorax. 1996;51:1216–22. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.12.1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gurgueira SA, Lawrence J, Coull B, et al. Rapid increases in the steady-state concentration of reactive oxygen species in the lungs and heart after particulate air pollution inhalation. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:749–55. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sorensen M, Daneshvar B, Hansen M, et al. Personal PM2.5 exposure and markers of oxidative stress in blood. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:161–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.111-1241344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shukla A, Timblin C, BeruBe K, et al. Inhaled particulate matter causes expression of nuclear factor (NF)-kappaB–related genes and oxidant-dependent NF-kappaB activation in vitro. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;23:182–7. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.23.2.4035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li N, Sioutas C, Cho A, et al. Ultrafine particulate pollutants induce oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:455–60. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Monn C, Becker S. Cytotoxicity and induction of proinflammatory cytokines from human monocytes exposed to fine (PM2.5) and coarse particles (PM10-2.5) in outdoor and in-door air. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1999;155:245–52. doi: 10.1006/taap.1998.8591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Becker S, Soukup JM. Exposure to urban air particulates alters the macrophage-mediated inflammatory response to respiratory viral infection. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 1999;57:445–57. doi: 10.1080/009841099157539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Monn C, Naef R, Koller T. Reactions of macrophages exposed to particles 10 microm. Environ Res. 2003;91:35–44. doi: 10.1016/s0013-9351(02)00021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mukae H, Vincent R, Quinlan K, et al. The effect of repeated exposure to particulate air pollution (PM10) on the bone marrow. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:201–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2002039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Salvi S, Blomberg A, Rudell B, et al. Acute inflammatory responses in the airways and peripheral blood after short-term exposure to diesel exhaust in healthy human volunteers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:702–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.3.9709083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salvi SS, Nordenhall C, Blomberg A, et al. Acute exposure to diesel exhaust increases IL-8 and GRO-alpha production in healthy human airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:550–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.2.9905052. (pt 1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ghio AJ, Hall A, Bassett MA, et al. Exposure to concentrated ambient particles alters hematologic indices in humans. Inhal Toxicol. 2003;15:1465–1478. doi: 10.1080/08958370390249111. Circulation June 1, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tan WC, Qiu D, Liam BL, et al. The human bone marrow response to acute air pollution caused by forest fires. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1213–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.4.9904084. (4 pt 1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seaton A, MacNee W, Donaldson K, et al. Particulate air pollution and acute health effects. Lancet. 1995;345:176–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Junker R, Heinrich J, Ulbrich H, et al. Relationship between plasma viscosity and the severity of coronary heart disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:870–5. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.6.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peters A, Döring A, Wichmann HE, et al. Increased plasma viscosity during an air pollution episode: a link to mortality? Lancet. 1997;349:1582–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)01211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Peters A, Perz S, Döring A, et al. Activation of the autonomic nervous system and blood coagulation in association with an air pollution episode. Inhal Toxicol. 2000;12:51–61. doi: 10.1080/08958378.2000.11463199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lind P, Hedblad B, Stavenow L, et al. Influence of plasma fibrinogen levels on the incidence of myocardial infarction and death is modified by other inflammation-sensitive proteins: a long-term cohort study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:452–8. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ridker PM, Rifai N, Stampfer MJ, et al. Plasma concentration of interleukin-6 and the risk of future myocardial infarction among apparently healthy men. Circulation. 2000;101:1767–72. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.15.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lindmark E, Diderholm E, Wallentin L, et al. Relationship between interleukin 6 and mortality in patients with unstable coronary artery disease: effects of an early invasive or noninvasive strategy. JAMA. 2001;286:2107–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.17.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Volpato S, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, et al. Cardiovascular disease, interleukin-6, and risk of mortality in older women: the Women’s Health and Aging Study. Circulation. 2001;103:947–53. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.7.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Eeden SF, Tan WC, Suwa T, et al. Cytokines involved in the systemic inflammatory response induced by exposure to particulate matter air pollutants (PM10) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:826–30. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.5.2010160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Toss H, Lindahl B, Siegbahn A, et al. for the FRISC study group Fragmin during Instability in Coronary Artery Disease. Prognostic influence of increased fibrinogen and C-reactive protein levels in unstable coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1997;96:4204–10. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.12.4204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ridker PM. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein: potential adjunct for global risk assessment in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2001;103:1813–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.13.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Peters A, Fröhlich M, Döring A, et al. Particulate air pollution is associated with an acute phase response in men: results from the MONICA-Augsburg study. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:1198–204. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fichtlscherer S, Rosenberger G, Walter DH, et al. Elevated C-reactive protein levels and impaired endothelial vasoreactivity in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2000;102:1000–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.9.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bhatt DL, Topol EJ. Need to test the arterial inflammation hypothesis. Circulation. 2002;106:136–40. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000021112.29409.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Libby P, Ridker PM, Maseri A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:1135–43. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Suwa T, Hogg JC, Quinlan KB, et al. Particulate air pollution induces progression of atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:935–42. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01715-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brook RD, Brook JR, Urch B, et al. Inhalation of fine particulate air pollution and ozone causes acute arterial vasoconstriction in healthy adults. Circulation. 2002;105:1534–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013838.94747.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Batalha JR, Saldiva PH, Clarke RW, et al. Concentrated ambient air particles induce vasoconstriction of small pulmonary arteries in rats. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:1191–7. doi: 10.1289/ehp.021101191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bonetti PO, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Endothelial dysfunction: a marker of atherosclerotic risk. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:168–75. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000051384.43104.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ikeda M, Watarai K, Suzuki M, et al. Mechanism of pathophysiological effects of diesel exhaust particles on endothelial cells. Environ Toxicol Pharm. 1998;6:117–23. doi: 10.1016/s1382-6689(98)00027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pekkanen J, Peters A, Hoek G, et al. Particulate air pollution and risk of ST-segment depression during repeated submaximal exercise tests among subjects with coronary heart disease: the exposure and Risk Assessment for Fine and Ultrafine Particles in Ambient Air (ULTRA) study. Circulation. 2002;106:933–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000027561.41736.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wellenius GA, Coull BA, Godleski JJ, et al. Inhalation of concentrated ambient air particles exacerbates myocardial ischemia in conscious dogs. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:402–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electroph,ysiology. Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Circulation. 1996;93:1043–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pope CA, Verrier RL, Lovett EG, et al. Heart rate variability associated with particulate air pollution. Am Heart J. 1999;138:890–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70014-1. (pt 1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liao D, Creason J, Shy C, et al. Daily variation of particulate air pollution and poor cardiac autonomic control in the elderly. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107:521–5. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Campen MJ, Costa DL, Watkinson WP. Cardiac and thermoregulatory toxicity of residual oil fly ash in cardiopulmonary-compromised rats. Inhal Toxicol. 2000;12(suppl 2):7–22. doi: 10.1080/08958378.2000.11463196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Godleski JJ, Verrier RL, Koutrakis P, et al. Mechanisms of morbidity and mortality from exposure to ambient air particles. Res Rep Health Eff Inst. 2000;91:5–88 discussion 89–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wellenius GA, Saldiva PH, Batalha JR, et al. Electrocardiographic changes during exposure to residual oil fly ash (ROFA) particles in a rat model of myocardial infarction. Toxicol Sci. 2002;66:327–35. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/66.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]