Abstract

The authors present a case of 36 year old male patient with idiopathic postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) diagnosed during head-up tilt testing. Power spectral analysis of heart rate variability (HRV) during the tilt test revealed that the ratio of low and high frequency powers (LF/HF) increased with the onset of orthostatic intolerance. This analysis confirmed in our patient a strong activation in sympathetic tone.

KEY WORDS: Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, POTS, Sympathovagal balance, Heart rate variability, HRV

INTRODUCTION

Orthostatic intolerance is defined by the inability to remain upright without severe signs and symptoms such as hypotension, tachycardia, lightheadedness, pallor, fatigue, weakness, and nausea. Orthostatic intolerance appears in many guises including overt dysautonomia, vasovagal syncope, and orthostatic tachycardia (1). POTS is operationally defined by the presence of symptoms of orthostatic intolerance associated with an increase in sinus heart rate of >30 beats/min or to a rate of >120 beats/min during the first 10 min of head up tilt table testing (2).

We report a case of POTS in which we analyze sympathovagal balance during Head Up Tilt Testing (HUTT).

CASE REPORT

A 36 year old man was referred to our hospital because of palpitations and lypotimia. He experienced presyncope on several occasions in the morning while waking up and when suddenly standing up from a sitting position, but syncope never developed. When he came to our observation, his body weight was 95 kg and his height was 170 cm. Physical examination was normal with blood pressure of 140/90 mmHg.

ECG showed sinus rhythm of 95 beats/minute without any conduction abnormalities or ST-T changes. Neither chest x-ray nor echocardiographic examination revealed any cardiac abnormalities.

Hematological examination, urine analysis and thyroid function were all normal. At clinical presentation, atrio-ventricolar slow-fast node re-entry tachycardia was initially suspected. This hypothesis was dismissed by electrophysiological transesophageus study. We performed a head-up tilt test to evaluate his orthostatic intolerance. The tilt test was done in a quiet room and in a fasting state. The ECG was monitored continuously and recorded to assess cardiac rhythm. Blood pressure was continuously monitored with an arterial tonometer (Sure Sign V1 Electronics, Philips) placed on the left radial artery, calibrated against oscillometric sphygmomanometer pressure. A continuous electrocardiographic recorder (Holter monitor ELA medical SYNETEC) was also attached for rhythm verification.

After resting for 10 min in the supine position, he was positioned upright at an angle of 80 degrees on a tilt table with a footboard for weight bearing. The passive tilt test was performed for a maximum of 45min. His heart rhythm (HR) was 85 beats/min and blood pressure was 130/80 mmHg in the supine position. After 3 min of the tilting, his HR abruptly increased to 150 beats/min and he began to complain of lightheadedness and weakness, but hypotension did not develop.

At the end of the passive tilt test for 45 min, he had not experienced syncope or marked hypotension and when he was returned to the supine position, HR quickly went back to normal as it was at the beginning of the test.

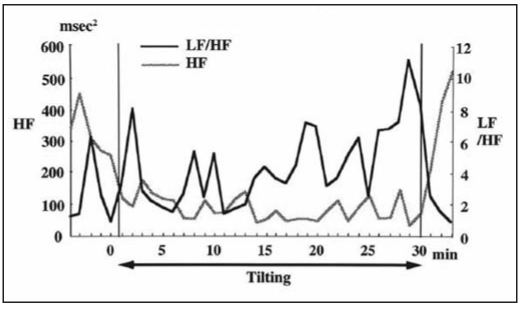

To analyze the patient’s sympathovagal balance during the head-up tilt testing, power spectral analysis of HR variability was performed using the ELA medical SYNETEC version 1.10 monitoring system. Spectral indices of HR variability were computed by Fast Fourier analysis for each 2-min interval with 1-min overlap during the passive tilt test. The power spectrum was calculated as high frequency (HF, 0.15–0.40 Hz), low frequency (LF, 0.05–0.15 Hz), and as the ratio of LF to HF power (LF/HF). The changes in HF and LF/HF during the tilt test are shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

- Changes in high-frequency (HF) power and in the ratio of low-frequency (LF) to HF power (LF/HF) during the passive tilt testing.

The LF/HF tended to fluctuate, but it reached a higher level after 25 min of tilting when the patient began to experience symptoms of orthostatic intolerance.

POTS diagnosis was made. He started therapy with atenolol 100 mg every morning. We suggested losing weight and increasing fluid intake about every three hours in the day. His symptoms of orthostatic intolerance resolved after about thirty days.

DISCUSSION

POTS has been described at least since 1940 and usually defined as the development of orthostatic symptoms associated with at least a 30 beat/minute increase in HR or a HR of =/>120 beats/ minute, that occurs within the first 10 minutes of standing on upright tilt without orthostatic hypotension (2). Patient’s age range is 10/60 years. HUTT is the POTS diagnosis gold standard; it is also useful to differentiate diagnosis between POTS and neurally mediated syncope (3, 4).

In this case report we studied dynamic changes in HR variability during tilt testing in a patient with POTS, to understand its physiopathological mechanism.

In the present case, LF/HF increased in parallel with the development of orthostatic intolerance without any changes in the HF value. This change in LF/HF may represent beta-receptor hyperactivity.

The suggested physiopathologic mechanisms included hypovolemia (5), excessive venous pooling while standing (6), loss of adequate vascular tone in the lower extremities and beta adrenergic hypersensitivity of cardiac receptors without appropriate baroreflex attenuation (7). Recently, an increased noradrenergic tone at rest and a blunted postganglionic sympathetic response to standing with compensatory cardiac sympathetic overactivity has been proposed (8). Recent genetic studies have demonstrated that a defective gene causes a dysfunction in a norepinephrine transporter protein, producing excessive serum norepinephrine levels. Impairment of synaptic norepinephrine clearance could produce a state of excessive sympathetic activation in response to physiologic stimuli (9). According to Schondorf et al attenuated post-viral panautonomic neuropathy could also be another cause of dysautonomia (10). Although no previous viral illness was identified in our patient, beta-receptor hypersensitivity may have played an important role in his orthostatic intolerance because this symptom was alleviated by beta-blocker therapy.

Tilt table testing is useful as a standardized measure of response to postural change in patients with dysautonomic alterations (4). In our patient, POTS diagnosis before HUTT was not easy because the orthostatic intolerance symptoms were compatible with neurally mediated syncope. Although there is considerable overlap in the symptoms between POTS and neurally mediated syncope, POTS symptoms (blunted postural tachycardia, disabling fatigue, light-headedness, dizziness) are never associated with significant blood pressure changes in contrast with neurological syncope patients, in whom hypotension is usually present; this may be due to different degrees of reflex neural inhibition (11). In POTS, the tachycardia induces a partial and selective reflex inhibition of muscle sympathetic nerve activity, blood pressure is maintained by the faster HR. In neurally mediated syncope, postural change may elicit a stronger neural inhibitory reflex that causes hypotension and bradycardia.

For POTS patients management it is important to change daily life style, to lose weight, to do mild aerobic exercises, to avoid alcohol excess, dyhydration and prevent hypovolemia while increasing fluid intake, and sleeping with the bed head slightly elevated (12). Our patient needed pharmacologic therapy with atenolol 100 mg every morning; his symptoms improved in about thirty days.

CONCLUSION

This case report underlines the usefulness of the head-up tilt testing in differentiating POTS from neurally mediated syncope in a patient with orthostatic intolerance. The HRV measure during HUTT in a patient with POTS studies sympathovagal balance. This analysis confirms in our patient a strongly activated sympathetic tone during a passive tilt with concomitant development of orthostatic intolerance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Low PA, Schondorf R, Novak V, Sandroni P, Opfer-Gehrking TL, Novak P. Postural tachycardia syndrome. In: Low PA, editor. Clinical autonomic disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott- Raven; 1997. pp. 681–97. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grubb BP, Kosinski DJ, Boehm K, Kip K. The postural orthostatic tachycardia syndromes: A neurocardiogenic variant identified during head-up tilt table testing. PACE. 1997;20:2205–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1997.tb04238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schondorf R, Low PA. Idiopathic postural orthostatic tachicardia syndrome: An attenuated form of acute pandysautonomia? Neurology. 1993;43:132–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.1_part_1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grubb BP, Kosinski D. Tilt table testing: Concepts and limitations. PACE. 1997;20:781–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1997.tb03904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacob G, Shannon JR, Black B, et al. Effects of volume loading and pressor agents in idiopathic orthostatic tachycardia. Circulation. 1997;96:575–80. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.2.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Low PA, Opfer-Gehrking TL, Textor SC, et al. Postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS) Neurology. 1995;45(Suppl 5):S19–S25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frohlich ED, Dustan HP, Page IH. Hyperdynamic beta-adrenergic circulatory state. Arch Intern Med. 1966;117:614–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furlan R, Jacob G, Snell M, et al. Chronic orthostatic intolerance: A disorder with discordant cardiac and vascular sympathetic control. Circulation. 1998;98:2154–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.20.2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shannon JR, Flattem NL, Jordan J, et al. Orthostatic intolerance and tachycardia associated with norepinephrine-transporter deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:541–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002243420803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schondorf R, Low PA. Idiopathic postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: An attenuated form of acute pandysautonomia? Neurology. 1993;43:132–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.1_part_1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Narkiewicz K, Somers VK. Chronic orthostatic intolerance: Part of a spectrum of dysfunction in orthostatic cardiovascular homeostasis? Circulation. 1998;98:2105–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.20.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grubb BP. The postural tachycardia syndrome: A brief review of etiology, diagnosis and treatment. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2002;43:47–52. [Google Scholar]