Abstract

An abnormal diastolic function of left ventricle represents the main pathophysiological mechanism responsible for different clinical states such as restrictive cardiomyopathy, infiltrative myocardial disease and, specially, diastolic heart failure (also called heart failure with preserved systolic function), which is present in a large number of patients with a clinical picture of pulmonary congestion.

Although the invasive approach, through cardiac catheterization allowing the direct measurement of left ventricular filling pressure, myocardial relaxation and compliance, is considered the gold standard for the identification of diastolic dysfunction, several noninvasive methods have been proposed for the study of left ventricular diastolic function.

Doppler echocardiography represents an excellent noninvasive technique to fully characterize the diastolic function in health and disease.

KEY WORDS: Diastolic function, Heart failure, Doppler echocardiography

INTRODUCTION

Left ventricular (LV) diastolic function is an essential component of the heart’s physiological adaptation to daily life. Altered diastolic function occurs in many conditions, such as acute and chronic ischemic cardiac disease (1), LV hypertrophy and heart failure (2, 3).

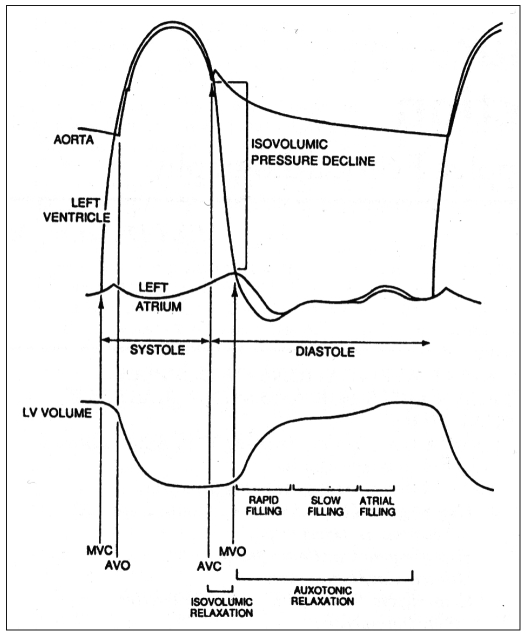

Diastole is a complex biochemical and physiological process that is subdivided into four consecutives phases (Fig. 1). These are determined by energy-dependent mechanisms, the biophysical characteristics of myocardial fibers and many other factors in both normal and pathologic conditions (4). Several indexes and techniques have been used in the study of diastolic function, but Doppler echocardiography currently represents, through the study of transmitral and pulmonary venous flow by pulsed wave (PW) Doppler (5–7), myocardial tissue Doppler (8–10) and intraventricular diastolic flow propagation velocity (11, 12), the best non-invasive approach for evaluating the diastolic function and classifying the different degrees of diastolic dysfunction.

Fig. 1.

- Schematic representation of the cardiac cycle. The different phases of diastole are indicated. See the text for details.

TRANSMITRAL FLOW PULSED WAVE DOPPLER

During sinus rhythm, pulsed Doppler transmitral flow shows two waves (Fig. 2 a–b). The first, called early (E) wave, is determined by the pressure gradient between the left atrium and left ventricle early after mitral valve opening during the left ventricle fast filling period (5, 6, 13). The second wave (A), which follows the E wave, appears during late diastole, and is the result of atrial contraction and the elastic proprieties of the left atrium and ventricle during late diastole. The E/A rate was one of the first diastolic function indices used (5, 6). Deceleration time (DT) of the E wave is well correlated with the left atrium mean pressure in different pathologic states. Another index is the isovolumetric relaxation time (IVRT), corresponding to the time from aortic valve closure to mitral valve opening (14, 15) (Fig. 3)

Fig. 2.

- Pulsed Doppler transmitral flow: a. the sample volume of pulsed Doppler is positioned at the tips of the mitral leaflets to record the tranmitral flow; b. example of pulsed Doppler flow at the mitral flow: the peak velocity in early dialstole and atrial systole are shown. The dotted line on descent of early filling wave indicates how to measure the deceleration time. See the text for details.

Fig. 3.

- Isovolumetric relaxation time (IVRT). The sample volume is positioned between the left ventricular outflow tract and the anterior mitral leaflet; the time interval between the end of aortic flow and the beginning of mitral flow (dotted lines) represents the IVRT. See the text for details.

PULMONARY VEIN FLOW PULSED WAVE DOPPLER

Pulsed Doppler flow of the pulmonary vein (usually the right upper pulmonary vein) in sinus rhythm is characterized by two anterograde waves, the systolic (S wave) and the diastolic (D wave) and a retrograde wave (Ar wave) during atrial systole (Fig. 4 a–b). In the presence of sinus bradycardia, it is possible to recognize the two components of the S wave: the first (S1) is due to blood inflow from the pulmonary veins during atrial diastole, the second (S2) is the consequence of the interaction of the right ventricle systolic volume and the left atrium compliance (14). The echocardiographic indices usually evaluated at the level of pulmonary venous flow are systolic (S) and diastolic (D) peaks, their ratio (S/D), time-velocity systolic wave integral, Ar wave peak velocity and duration, and Ar - mitral A wave time difference (as an index of LV end-diastolic pressure) (7).

Fig. 4.

- Pulsed Doppler flow of pulmonary vein: a. the sample volume of pulsed Doppler is positioned in the upper pulmonary vein (usually the right), just before its entry in the left atrium; b. anterograde flow in systole and early diastole and retrograde flow during atrial contraction are shown. See the text for details.

OTHER DOPPLER ECHOCARDIOGRAPHIC APPROACHES

Tissue Doppler of the mitral annulus

In healthy adults tissue PW Doppler of the mitral annulus is made up of a positive systolic wave (Sm) and two negative diastolic waves similar to transmitral flow in PW Doppler, an early (Em) and a late one (Am), during atrial systole (Fig. 5 a–b). This diastolic pattern is independent of, or at least less dependent on, ventricular preload variations, compared to Doppler mitral flow. Mitral E/Em ratio can be used as a reliable non-invasive index of LV filling pressure (Fig. 6) (8, 10).

Fig. 5.

- Tissue pulsed Doppler of the mitral annulus: a. the sample volume is positioned at the lateral segment of mitral annulus; b. peak tissue Doppler velocity in early diastole and atrial contraction are shown. See the text for details.

Fig. 6.

- Correlation between mitral E/Em ratio on tissue Doppler of mitral annulus and left ventricular filling pressure (modified from Nagueh et al (8)). See the text for details.

Color M-mode transmitral-flow velocity

During the early filling phase, it is possible to register from the base to the apex of the left ventricle a consecutive series of intracavitary pressure gradients, which lead to flow propagation from the mitral annulus to the apex. It is possible to measure this propagation velocity using color M-mode by placing the M-mode cursor in the centre of the color spectrum of the left ventricle inflow tract. By measuring the outside edge slope of the color protodiastolic velocity, about 4 cm below the mitral valve plane, the propagation velocity (Vp) is obtained, a relatively preload-independent index well correlated with the tau constant at left heart catheterization (11, 12).

DOPPLER PATTERNS OF DIASTOLIC DYSFUNCTION

Three different patterns of transmitral flow have been described, in pathologic conditions - impaired relaxation, pseudonormal and restrictive pattern - corresponding to a different severity of diastolic dysfunctions (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

- Different Doppler patterns of diastolic dysfunction: modified from Zile et al (21). See the text for details.

The impaired relaxation pattern of transmitral flow, usually considered the lightest form of diastolic dysfunction (degree I), is characterized by a prolonged isovolumetric relaxation time (usually >100 msec), a smaller E wave peak, with a prolonged deceleration time (DT >200–220 msec), an increased A wave peak, and a lower E/A ratio (<1). Likewise, in pulmonary vein flow S/D ratio is >1 whereas Ar wave peak may be significantly increased (from −20 to −28−30 cm/sec). Finally, Em mitral annulus velocity width at TDI is quite reduced (<8–10 cm/sec) and color M-mode propagation velocity is <45 cm/sec.

In patients with pseudonormal or normalized pattern (degree II diastolic dysfunction), transmitral flow is similar to normal, but pulmonary flow S velocity peak is reduced, S/D ratio is <1, Ar velocity peak and duration are increased; Ar-mitral A difference is ≥20–30 msec, reflecting high filling pressure. TDI Em velocity, which is independent of preload variations and left atrial pressure, is reduced (usually <8 cm/sec), confirming an impaired relaxation. It is very important to differentiate between truly normal and pseudonormal patterns and the combined use of transmitral flow, pulmonary vein flow and mitral annulus TDI is generally necessary. The behavior of transmitral flow during preload manipulations (for example, the Valsalva maneuver) may allow the correct diagnosis. When preload is reduced, during the strain phase of Valsalva, anormal filling patterns show a similar reduction of E and A velocity, on the other hand, a pseudonormal pattern changes to an impaired relaxation pattern (peak E wave velocity reduces more than A wave (16, 17)) (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

- The effect of valsalva maneuver on pulsed Doppler of transmitral flow in order to differentiate between the true normal and pseudonormal left ventricular filling pattern. See the text for details.

With advanced degrees of diastolic dysfunction and the progressive increase of mean left atrial pressures, a very high E wave and a low A wave usually occur at transmitral flow, with E/A ratio >2, associated with reduced DT (<150 msec); IRVT is also shorter than normal (<60 msec). This pattern of transmitral flow is referred to as restrictive filling pattern, or degree III of diastolic dysfunction (16). The large flow during rapid filling (prominent E wave) is caused by elevated early diastolic atrioventricular pressure gradient. The short duration of early filling flow reflects the elevated left ventricle wall stiffness, with rapid equalization of ventricular and atrial diastolic pressure (short DT). On the pulmonary vein flow, the systolic wave is reduced or absent and Ar width and duration are increased (14, 16). At TDI, Em peak and color M-mode propagation velocity are reduced since they are preload-independent or less preload-dependent, compared to other Doppler parameters (18). A reversible restrictive pattern can usually be modified by therapeutic interventions to less advanced stages of diastolic dysfunction. However, in some pathologic states, due to severe abnormalities of diastolic properties of the ventricular walls and a marked increase in filling pressure, the restrictive pattern cannot respond to load manipulations (irreversible or fixed). Furthermore, Doppler abnormalities of left atrial dysfunction or failure can also be observed on Doppler profile of transmitral and pulmonary venous flow, characterized by a low and short duration atrial wave (13, 16).

NON-INVASIVE MEASUREMENT OF LEFT VENTRICULAR FILLING PRESSURES

Studying diastolic function by echocardiograph allows a fairly reliable and reproducible measurement of filling pressures and their variations determined by disease progression and/or therapeutic interventions (6–12, 14, 19–21). In some studies, transmitral flow E/A ratio and DT have shown a correlation (from satisfactory to very good) with invasively measured mean left atrial pressure. Another Doppler index that correlates well with left atrial pressure is the systolic pulmonary vein flow wave. The higher the atrial pressure, the lower the peak velocity and time-velocity S wave integral (22). Furthermore, Ar length is increased in patients with increased end-diastolic LV pressure, whereas mitral A wave length is reduced; therefore, Ar-mitral A length difference has a fairly good correlation with invasively measured atrial pressure (7). Finally, mitral E–TDI Em ratio (the latter preload-independent) has also shown a good correlation with mean left atrial pressure (Fig. 6) (8).

DOPPLER ECHOCARDIOGRAPHIC STUDY OF LEFT VENTRICULAR DIASTOLIC FUNCTION IN DISEASES: ITS IMPORTANCE IN CLINICAL MANAGEMENT

Systemic hypertension and left ventricle hypertrophy

Systemic hypertension is generally responsible for degree I diastolic dysfunction, especially in the initial stage of the disease. Even though the main cause is left ventricle hypertrophy (due to chronic pressure overload), some studies have shown that diastolic dysfunction can occur in systemic hypertension despite a normal left ventricle mass and preserved systolic function (23). Some authors have suggested that left ventricle pressure overload could lead per se to an impaired relaxation, and/or that moderate interstitial fibrosis (even without an increase in ventricular mass) in response to pressure stimulus could lead to diastolic abnormality (24–26). In more advanced stages of hypertensive cardiopathy, a pseudonormal pattern or even a restrictive pattern can be observed, indicating an increase of LV filling pressure and some degree of left atrial dysfunction (24).

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Asymmetric obstructive and non-obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is another condition with increased left ventricle mass (27), (28), which can result in diastolic dysfunction. Mitral flow and pulmonary vein flow at PW Doppler are usually characterized by degree I dysfunction. Relaxation abnormalities in such patients are due to wall hypertrophy and myocardial fiber disarray.

Dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure due to systolic dysfunction

Dilatation and dysfunction of the left ventricle, whether symptomatic or not, whatever the etiology, can occur with each pattern of left ventricle filling described above. There is usually a poor correlation between LV ejection fraction and filling pattern. Some patients can have a severe reduction in systolic function (LVEF <30%) and an impaired relaxation, a pseudonormalized or a restrictive LV filling pattern; filling pattern, on the other hand, depends on and indicates the level of diastolic pressure in the left atrium and left ventricle (normal, mildly and markedly increased, respectively). This confirms that the severity of the clinical picture depends on several factors, such as peripheral abnormalities, contractile status, functional, mitral regurgitation, but also diastolic myocardial properties, and hence filling pressure. Interestingly, the LV filling pattern has a strong prognostic role in heart failure patients, independent of and additive to other common parameters, such as LV ejection fraction, New York Heart Association, renal function, hyponatremia, etc (15, 16).

Restrictive cardiomyopathy and constrictive pericarditis

The term restrictive cardiomyopathy is generally used to identify heart failure states without LV dilatation, but with hypertrophy of the ventricular walls (29). Disorders included under restrictive cardiomyopathy are amyloidosis, hemochromatosis, endomyocardial fibroelastosis, infiltrative disorders (such as Fabry’s disease, Gaucher’s disease and eosinophilic endomyocardial fibrosis) and idiopathic restrictive cardiomyopathy (29, 30). Clinical manifestations are usually secondary to diastolic dysfunction (impaired relaxation and reduced compliance of the left ventricle) with hemodynamic abnormalities (increased ventricular filling pressures and left atrial pressure) identified by the restrictive pattern at mitral PW Doppler.

Restrictive physiology is also the main physiopathologic mechanism of constrictive pericarditis, a rare but serious clinical condition (30). Fibrous thickening of the serosa and pericardial calcifications were once consequences of tuberculosis, but they now occur as late sequelae of heart surgery or radiotherapy. A relevant limitation occurs in heart chamber filling (the whole heart volume is fixed in systole and diastole), especially during fast filling, causing an early increase and equalization of both right and left atrial and ventricular diastolic pressures. The Doppler profiles are similar in restrictive cardiomyopathy and constrictive pericarditis patients. Changes observed during respiration can contribute to differential diagnosis. In constrictive pericarditis, during inspiration there is a greater reduction in diastolic pulmonary vein flow (D wave) and transmitral fast filling (E wave) (Fig. 8), whereas tricuspid E wave increases, due to venous return. During expiration, there is an increase in E wave peak velocity (usually >25% compared to the inspiratory phase), pulmonary vein flow S and D waves, and a reduction in tricuspidal E wave (31, 32). Respiratory changes are usually absent in restrictive cardiomyopathy patients.

Diastolic heart failure

Epidemiologic studies have shown that about 40% of patients admitted to hospital with heart failure have preserved LV ejection fraction (33); accordingly, the clinical picture is usually attributed to isolated diastolic dysfunction. In these patients, impaired relaxation and especially abnormal elastic properties (compliance) of the left ventricle are secondary to diastolic pressure-volume curve relation, which moves up and to the left compared with healthy subjects and patients with systolic heart failure (34). In a review of 31 studies (from 1970–1995), the prevalence of isolated diastolic dysfunction ranged from 13–74%, being around 40% in most studies (33).

According to ACC/AHA guidelines, a diagnosis of heart failure with preserved systolic or diastolic dysfunction can be made when there are signs and symptoms of heart failure with normal left ventricle ejection fraction (35). On the other hand, according to the European Study Group on diastolic heart failure, the diagnosis of diastolic heart failure requires the simultaneous presence of signs and symptoms of heart failure, the demonstration of normal left ventricle ejection fraction and the evidence of diastolic dysfunction by invasive or non-invasive approaches (36). This approach requires a careful assessment of several diastolic function parameters (adjusted for sex and age).

CONCLUSIONS

The study of diastolic function by Doppler echocardiography is complex and demanding. The cardiologist/echocardiologist must have a systematic approach to the study of diastolic function, not only based on the Doppler index, but integrating Doppler patterns with other echo-parameters (chamber diameters, wall thickness, systolic function, valve function and morphology) and clinical information. A rational interpretation of clinical and instrumental data can allow a correct diagnosis, which is essential for clinical decision-making.

At the time this review was accepted for publication, the Heart Failure and Echocardiography Associations of the European Society of Cardiology published a Consensus Statement on the diagnosis of Diastolic Heart Failure (Eur Heart J 2007 Apr 11; (Epub ahead of print)), in which the role of an integrated approach including a careful clinical examination, a comprehensive Doppler echocardiographic evaluation and the use of cardiac biomarkers, such as natriuretic peptides, is emphasized.

REFERENCES

- 1.Reduto LA, Wickemeyer WJ, Young JB, et al. Left ventricular diastolic performance at rest and during exercise in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1981;63:1228–37. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.63.6.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Packer M. Abnormalities of diastolic function as a potential cause of exercise intolerance in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 1990;81(suppl):III78–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng KSK, Gibson DG. Relation of filling pattern to diastolic function in severe left ventricular disease. Br Heart J. 1990;63:209–14. doi: 10.1136/hrt.63.4.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kass DA, Bronzwaer JGF, Paulus WJ. What mechanisms underlie diastolic dysfunction in heart failure? Circ Res. 2004;94:1533–42. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000129254.25507.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Appleton CP, Hatle LK, Popp RL. Relation of transmitral flow velocity patterns to left ventricular diastolic function: new insights from a combined hemodynamic and Doppler echocardiographic study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;12:426–40. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(88)90416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mulvagh S, Quinones MA, Kleiman NS, Cheirif J, Zoghbi WA. Estimation of left ventricular end-diastolic pressure from Doppler transmitral flow velocity in cardiac patients independent of systolic performance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:112–9. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90146-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Appleton CP, Galloway JM, Gonzalez MS, Gaballa M, Basnight MA. Estimation of left ventricular filling pressures using two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography in adult patients with cardiac disease: additional value of analyzing left atrial size, left atrial ejection fraction and the difference in duration of pulmonary venous and mitral flow velocity at atrial contraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22:1972–82. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90787-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagueh SF, Middleton KJ, Kopelen HA, Zoghbi WA, Quinones MA. Doppler tissue imaging: a noninvasive technique for evaluation of left ventricular relaxation and estimation of filling pressure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1527–33. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00344-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sohn DW, Chai I, Lee DJ, et al. Assessment of mitral annulus velocity by Doppler tissue imaging in the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:474–80. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)88335-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang M, Yip GW, Wang AY, et al. Peak early diastolic mitral annulus velocity by tissue Doppler imaging adds independent and incremental prognostic value. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:820–6. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02921-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brun P, Tribouilloy C, Duval AM, et al. Left ventricular flow propagation during early filling is related to wall relaxation: a color M-mode Doppler analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:420–32. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90112-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia MJ, Smedira NG, Greenberg NL, et al. Color M-mode Doppler flow propagation velocity is a preload insensitive index of left ventricular relaxation: animal and human validation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:201–8. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00503-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishimura RA, Abel MD, Hatle LK, Tajik AJ. Assessment of diastolic function of the heart: background and current applications of Doppler echocardiography. Part II, clinical studies. Mayo Clin Proc. 1989;64:181–204. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)65673-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Appleton CP, Firstenberg MS, Garcia MJ, Thomas JD. The echo-Doppler evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function. A current perspective. Cardiol Clin. 2000;18:513–46. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8651(05)70159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galderisi M, Dini FL, Temporelli PL, Colonna P, de Simone G. [Doppler echocardiography for the assessment of left ventricular diastolic function: methodology, clinical and prognostic value] Ital Heart J Suppl. 2004;5:86–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishimura RA, Tajik AJ. Evaluation of diastolic filling of left ventricle in health and disease: Doppler echocardiography is the clinician’s Rosetta Stone. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:8–18. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rakowski H, Appleton C, Chan K-L, et al. Canadian consensus recommendations for the measurement and reporting of diastolic dysfunction by echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1996;9:736–60. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(96)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagueh SF, Mikati I, Kopelen HA, Middleton KJ, Quinones MA, Zoghbi WA. Doppler estimation of left ventricular filling pressure in sinus tachycardia. A new application of tissue Doppler imaging. Circulation. 1998;98:1644–50. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.16.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quinones MA, Otto CM, Stoddard M, et al. Recommendations for quantification of Doppler echocardiography: a report from the Doppler Quantification Task Force of the Nomenclature and Standards Committee of the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002;15:167–84. doi: 10.1067/mje.2002.120202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lehhningern AL. Ca2+ transport by mitochondria and its possible role in the cardiac contraction-relaxation cycle. Circ Res. 1974;35(suppl 3):S83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zile MR. Diastolic dysfunction: detection, consequences and treatment. Part I: definition and determinants of diastolic function. Mod Concepts Cardiovasc Dis. 1989;58:67–76. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuecherer HF, Muhiudeen IA, Kusumoto FM, et al. Estimation of mean left atrial pressure from transesophageal pulsed Doppler echocardiography of pulmonary venous flow. Circulation. 1990;82:1127–39. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.4.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faggiano P, Rusconi C, Orlando G, et al. Assessment of left ventricular filling in patients with systemic hypertension. A Doppler echocardiographic study. J Hum Hypertension. 1989;3:149–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Simone G, Palmieri V. Diastolic dysfunction in arterial hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2001;3:22–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2001.00827.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu JE, Palmieri V, Roman MJ, et al. The impact of diabetes on left ventricular filling pattern in normotensive and hypertensive adults: the Strong Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1943–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01230-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Simone G, Kitzman DW, Chinali M, et al. Left ventricular concentric geometry is associated with impaired relaxation in hypertension: the HyperGEN study. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1039–45. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faggiano P, Sabatini T, Rusconi C, Ghizzoni G, Sorgato A. Abnormalities of left ventricular filling in valvular aortic stenosis. Usefulness of combined evaluation of pulmonary veins and mitral flow by means of transthoracic Doppler echocardiography. Int J Cardiol. 1995;49:77–85. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(95)02275-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maron BJ, Spirito P, Green KJ, Wesley YE, Bonow RO, Arce J. Noninvasive assessment of left ventricular diastolic function by pulsed Doppler echocardiography in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987;10:733–42. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(87)80264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodwin JF, Gordon H, Hollman A, Bishop MB. Clinical aspects of cardiomyopathy. BMJ. 1961;i:69–79. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5219.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hancock EW. Differential diagnosis of restrictive cardiomyopathy and constrictive pericarditis. Heart. 2001;86:343–9. doi: 10.1136/heart.86.3.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oh JK, Hatle L, Seward JB, et al. Diagnostic role of Doppler echocardiography in constrictive pericarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:154–62. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hatle L, Appleton CP, Popp RL. Differentiation of constrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy by Doppler echocardiography. Circulation. 1989;79:357–70. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.2.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Prevalence, clinical features and prognosis of diastolic heart failure: an epidemiologic perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:1565–74. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00381-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aurigemma GP, Gaasch WH. Clinical practice. Diastolic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1097–105. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp022709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.ACC/AHA 2005 Guideline Update for the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Heart Failure in the Adult. A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure) doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.08.022. www.acc.org. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.How to diagnose diastolic heart failure. European study group on Diastolic Heart Failure. Eur Heart J. 1998;19:990–1003. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1998.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]