Abstract

Background

Some believe that a substantial amount of US health care is unnecessary, suggesting that it would be possible to control costs without rationing effective services. The views of primary care physicians—the frontline of health care delivery—are not known.

Methods

Between June and December 2009, we conducted a nationally representative mail survey of US primary care physicians (general internal medicine and family practice) randomly selected from the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile (response rate, 70%; n=627).

Results

Forty-two percent of US primary care physicians believe that patients in their own practice are receiving too much care; only 6% said they were receiving too little. The most important factors physicians identified as leading them to practice more aggressively were malpractice concerns (76%), clinical performance measures (52%), and inadequate time to spend with patients (40%). Physicians also believe that financial incentives encourage aggressive practice: 62% said diagnostic testing would be reduced if it did not generate revenue for medical subspecialists (39% for primary care physicians). Almost all physicians (95%) believe that physicians vary in what they would do for identical patients; 76% are interested in learning how aggressive or conservative their own practice style is compared with that of other physicians in their community.

Conclusions

Many US primary care physicians believe that their own patients are receiving too much medical care. Malpractice reform, realignment of financial incentives, and more time with patients could remove pressure on physicians to do more than they feel is needed. Physicians are interested in feedback on their practice style, suggesting they may be receptive to change.

Per capita us health care spending exceeds, by a factor of 2, that of the average industrialized nation and is growing at an unsustainable rate.1 Many worry that controlling medical costs inevitably would lead to the rationing of effective services. A number of health care epidemiologists and economists, however, have suggested that a substantial amount of US health care is actually unnecessary.2–4 They believe that we can “bend the cost curve”5 without rationing by reducing this unnecessary care.

What do practicing physicians believe? The views of primary care physicians—the frontline of health care delivery—are not known. But they matter. Primary care physicians are uniquely positioned to oversee most of the care that patients receive. Because they both manage their own patients and are the source of most referrals to other physicians, primary care physicians are at least indirectly responsible for initiating the cascade of health care utilization (testing, therapies, and hospitalizations) for most patients.6,7 We therefore surveyed US primary care physicians about whether they think patients are receiving too much or too little medical care and what factors influence how aggressively or conservatively they practice.

METHODS

We conducted a national mail survey of 627 practicing US adult primary care physicians (response rate, 70%) identified from a random sample of the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile.8 The survey, conducted in collaboration with Harris Interactive, a professional survey research firm, was approved by the institutional review board at Dartmouth Medical School.

Physicians received up to 3 mailings of the 9-page survey (see relevant survey content in eAppendix; http://www.archinternmed.com) and between $20 and $100 (varying due to an embedded methodology study). Because physicians in focus groups and cognitive interviews spontaneously used the terms aggressive and conservative to describe practice styles of ordering of diagnostic tests and referrals, we adopted these terms in the survey. All analyses were carried out in STATA 10.0 statistical software (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

PHYSICIAN CHARACTERISTICS

Respondents were mostly male (72%), graduates of US or Canadian medical schools (81%), and board certified (88%); reported a median of 24 years in practice; and were fairly evenly divided between family medicine (54%) and internal medicine (43%).

BELIEFS ABOUT THE INTENSITY OF AMERICAN MEDICAL PRACTICE

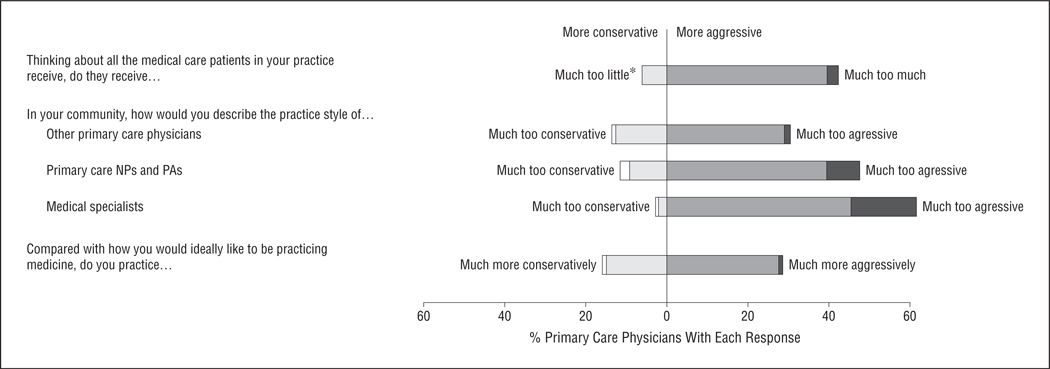

Almost half (42%) of US primary care physicians believed that patients within their own practice were receiving too much medical care (Figure); just 6% believed that their patients were receiving too little care (52% thought that the amount was just right). More than one-quarter (28%) said they themselves were practicing more aggressively (ie, ordering more tests and referrals) than they would ideally like to be, almost identical to the proportion (29%) who believed that other primary care physicians in their community were practicing too aggressively. Respondents were much more likely to report that mid-level primary care providers (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) (47%) and medical subspecialists (61%) practice too aggressively (P<.001 for each group compared with primary care physicians).

Figure.

Primary care physicians’ opinions (n=627) on the style of medical care practiced in their communities. The most extreme responses (along a 5-point Likert scale) are shaded in white and black; gray shading represents the intermediate responses (eg, “too little” and “too much” for the first question). The neutral category (eg, “just about right”) is omitted from the Figure. Item nonresponse for the 5 questions, in order, was 1.3%, 2.6%, 5.6%, 2.6%, and 2.2%. *No physicians responded “much too little.” NPs indicates nurse practitioners; PAs, physician assistants.

Many physicians (45%) estimated that at least 1 in 10 patients they see on a typical day could be handled in ways other than a physician visit (eg, by telephone, e-mail, or nonphysician staff such as nurses).

FACTORS INFLUENCING THE INTENSITY OF TESTING AND REFERRAL

Physicians identified 3 factors causing them to practice more aggressively: inadequate time to spend with patients (40%), clinical performance measures (52%), and malpractice concerns (76%) (eFigure). The way that malpractice concerns lead to more aggressive practice was clear: 83% of physicians thought they could easily be sued for failing to order a test that was indicated, but only 21% thought they could be sued for ordering a test that was not indicated. While few physicians believed that financial considerations influenced their own practice style (3%), most thought they affected other physicians. Specifically, 39% believed that other primary care physicians would order fewer diagnostic tests if such tests did not generate extra revenue; almost two-thirds (62%) said that medical subspecialists would cut back on testing in the absence of a financial incentive.

VARIATION IN PRACTICE

Respondents overwhelmingly (95%) believed that primary care physicians vary in their testing and treatment decisions for similar patients. Most (76%) were interested in learning how their own practice pattern compared with that of other physicians; 65% requested a report we offered on how practice in their own community compared with others.

COMMENT

Nearly half of all primary care physicians in the United States think that their own patients are receiving too much medical care, and more than one-quarter believe that they themselves are practicing too aggressively. Even more are concerned about overly aggressive practice among midlevel primary care providers and medical subspecialists. Our findings show that many primary care physicians believe there is substantial unnecessary care that could be reduced, particularly by increasing time with patients, reforming the malpractice system, and reducing financial incentives to do more.

Prior work has also implicated financial incentives9–11 and malpractice12–14 as important factors promoting aggressive practice. The extent to which fear of malpractice leads to more aggressive practice (so-called defensive medicine) has been hotly debated15; based on our findings, we believe it is not a small effect. Estimates that have relied on differences in malpractice risk across communities ignore the likelihood that the pervasive threat of litigation leads all physicians to practice more aggressively—to an extent that is not easily predictable.

Our work suggests 2 additional factors that encourage more aggressive practice. Inadequate time with patients may force physicians to turn instead to testing or referrals to solve clinical questions,16 a hypothesis supported by work showing that a telephone triage system with shorter call durations was associated with more patients referred to see a physician.17 The proliferation of clinical performance measures may encourage utilization—and, paradoxically, lower quality of care—by promoting uncritical adherence to interventions of increasingly tiny benefit.18

Several limitations of our study deserve mention. As with any survey, nonresponse limits generalizability; our response rate of 70%, however, is exceptional for a survey of American physicians. Second, some may believe that our primary finding was based on an overly simplified construct, that is, are patients receiving too much or too little health care. We found, however, that physicians instinctively discussed the experiences of their patients using this language. Lastly, we cannot know to what extent physicians are able to accurately report the role of specific influences on their practice behavior.

We believe that our findings have important implications for health care reform in the United States—efforts that undeniably depend on the engagement of physicians.19,20 Primary care physicians believe that many patients receive too much care. They recognize that practice patterns vary across communities and most would like to know where they stand in comparison with their peers. Taken together, we believe our findings suggest that physicians are open to practicing more conservatively.

A lot will have to happen if practice is to change. There needs to be a fundamental realignment of financial incentives and reform of the malpractice system. Physicians believe they are paid to do more and exposed to legal punishment if they do less. Reimbursement systems should encourage longer primary care physician visits and telephone, e-mail, and nursing follow-up, rather than diagnostic intensity. Caution is warranted for policy solutions that promote increased reliance on midlevel primary care providers and clinical performance measures, efforts that may ironically increase utilization.

Our work shows that primary care physicians recognize the excesses of our health care system, can point clearly to some of the causes, and may be open to changing their own practices to address them.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by a Veterans Affairs Merit Review grant for Investigator Initiated Research (IIR 03–242) in HSR&D. This study was also supported in part by a grant PO1 AG19783 from the National Institute of Aging.

Role of the Sponsors: The funding organizations played no role in the study design and conduct; in the data collection, management, and interpretation; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: Sirovich, Woloshin, and Schwartz. Acquisition of data: Sirovich. Analysis and interpretation of data: Sirovich, Woloshin, and Schwartz. Drafting of the manuscript: Sirovich. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Sirovich, Woloshin, and Schwartz. Statistical analysis: Sirovich. Obtained funding: Sirovich. Administrative, technical, and material support: Woloshin and Schwartz. Study supervision: Sirovich, Woloshin, and Schwartz.

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

Disclaimer: The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

Previous Presentation: The information reported in this manuscript was previously accepted as an abstract for presentation at the 2010 annual meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine, entitled “Primary Care Physicians’ Prescription for US Health Care Reform: Less May Be More”; April 28–May 1, 2010; Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Online-Only Material: The eAppendix and eFigure are available at http://www.archinternmed.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.White C. Health care spending growth: how different is the United States from the rest of the OECD? Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(1):154–161. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.1.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bentley TG, Effros RM, Palar K, Keeler EB. Waste in the US health care system: a conceptual framework. Milbank Q. 2008;86(4):629–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2008.00537.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landrum MB, Meara ER, Chandra A, Guadagnoli E, Keating NL. Is spending more always wasteful? the appropriateness of care and outcomes among colorectal cancer patients. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(1):159–168. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gawande AA, Fisher ES, Gruber J, Rosenthal MB. The cost of health care—highlights from a discussion about economics and reform. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(15):1421–1423. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0907810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brook RH, Young RT. The primary care physician and health care reform. JAMA. 2010;303(15):1535–1536. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisenberg JM. Physician utilization: the state of research about physicians’ practice patterns. Med Care. 2002;40(11):1016–1035. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000032181.98320.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Reilly KB. AMA meeting: are doctors responsible for controlling health care costs? [Accessed May 17, 2010];American Medical News. 2009 November 23; http://www.ama-assn.org/amednews/.

- 8.American Medical Association. [Accessed July 20, 2011];Physician data resources. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/about-ama/physician-data-resources/physician-masterfile.page?.

- 9.Shen J, Andersen R, Brook R, Kominski G, Albert PS, Wenger N. The effects of payment method on clinical decision-making: physician responses to clinical scenarios. Med Care. 2004;42(3):297–302. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000114918.50088.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gosden T, Forland F, Kristiansen IS, et al. Capitation, salary, fee-for-service and mixed systems of payment: effects on the behaviour of primary care physicians. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(3):CD002215. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rice TH. The impact of changing Medicare reimbursement rates on physician-induced demand. Med Care. 1983;21(8):803–815. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198308000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin GA, Dudley RA, Redberg RF. Why physicians favor use of percutaneous coronary intervention to medical therapy: a focus group study. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1458–1463. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0706-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baicker K, Fisher ES, Chandra A. Malpractice liability costs and the practice of medicine in the Medicare program. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(3):841–852. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2609–2617. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.21.2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kessler DP, Summerton N, Graham JR. Effects of the medical liability system in Australia, the UK, and the USA. Lancet. 2006;368(9531):240–246. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.González-González AI, Dawes M, Sánchez-Mateos J, et al. Information needs and information-seeking behavior of primary care physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(4):345–352. doi: 10.1370/afm.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ong RSG, Post J, van Rooij H, de Haan J. Call-duration and triage decisions in out of hours cooperatives with and without the use of an expert system. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-9-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Werner RM, Asch DA. Clinical concerns about clinical performance measurement. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(2):159–163. doi: 10.1370/afm.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antiel RM, Curlin FA, James KM, Tilburt JC. Physicians’ beliefs and US health care reform—a national survey. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(14):e23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0907876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher ES, Berwick DM, Davis K. Achieving health care reform—how physicians can help. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(24):2495–2497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0903923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]