Abstract

Purpose

We surveyed residents and fellows at the University of Louisville School of Medicine (N = 600) to (1) explore their perceptions and knowledge of issues related to health care business and health care reforms, and (2) seek their input on what instructional content concerning health care business and health care reform they would like to receive and what instruction venue they would prefer. We will use the findings to make decisions about curriculum content and delivery.

Methods

All residents were invited to complete a 4-part, web-based survey that included questions on demographics, attitudes, and perceptions; a baseline-knowledge quiz about health care costs; and 2 open-ended questions about what they wanted to learn and how they preferred to be taught.

Results

The survey response rate was 24%. Residents' agreement was stronger for statements relating to the role of physicians as “gatekeepers,” patient-centered care, and the value of learning to work as a team than it was for statements about the benefits of government intervention in health care. International medical graduates, when compared with US medical graduates, had statistically significant differences in perceptions (P ≤ .004) on 3 questions related to government impact on health care. There was a slight decrease in overall knowledge about health care cost issues by residents in later postgraduate years.

Conclusion

Residents are aware of gaps in their knowledge on business aspects of health care and health care reform. Their narrative responses identified coding and billing, legal issues, and comparative health systems as topics of interest, and the best venues for teaching included grand rounds and noon conferences. Residents indicated a preference for brief, highly focused, interactive sessions with knowledgeable guest speakers.

Introduction

Concerns about health care costs and health care reform in the United States have become more contentious in the past 20 years. In 1990, the American College of Physicians argued that physicians' involvement in health care reform was critical to the success of efforts.1 In 1992, a survey of the perceptions of medical school seniors on current trends in the US health care delivery system found 84% of respondents agreeing that learning to work in teams of health care professionals should be included in the medical education curriculum and 82% agreeing that learning to work in a managed care environment should become a part of the curriculum.2 In contrast with these expressed student interests, Veloski et al3 found that only 16% of medical schools required all students to have clinical experiences in a managed care setting. Although 85% of students were exposed to different types of managed care, the experiences did not address features unique to managed care, such as cost containment and disease prevention.3

In 2009, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission4 reported data from a Rand Corporation (Santa Monica, CA) study and concluded that many residency programs are “not well aligned with objectives of delivery system reform.”4(p4) Specific concerns included a lack of (1) formal instruction in multidisciplinary teamwork, (2) cost awareness in clinical decision-making, (3) comprehensive health information technology, and (4) patient care in ambulatory settings.4

The solution is to add health care business and health care reform topics to the graduate medical education curriculum. Two issues limit the development of this curriculum: (1) there is little information on what medical students and residents already know about the business of health care, and (2) the health care system in this country is currently undergoing major reforms. Using the Rothwell and Kazanas5 model for instructional design, we identified needs assessment and content analysis as the first 2 tasks necessary for curriculum development.

The purpose of this study was to survey residents and fellows (N = 600) at the University of Louisville School of Medicine to (1) measure their perceptions and knowledge of issues related to health care business and health care reforms, and (2) seek their input on what instructional content concerning health care business and health care reform should be provided and what venue they prefer for that instruction. We will apply the findings to curriculum content and delivery decisions.

Methods

The study was reviewed and deemed exempt by the University of Louisville Institutional Review Board (November 13, 2009, No. 09.0544). We applied a nonexperimental, cross-sectional, descriptive design.

Survey Design

The online survey had 4 sections: (1) 3 demographic questions; (2) 5-point Likert-scale questions (n = 14) on the degree of agreement with various perceptions and attitudes on the business of health care; (3) a 5-question, multiple-choice quiz testing knowledge about health care costs; and (4) 2 open-ended questions asking about content and venue.

We based the perception and attitude questions on the survey developed by Hojat et al,2 using the same 5 categories: quality, financial, referral, education, and other; and the knowledge questions from an online survey originally developed by the Graziadio Business Report, Pepperdine University.6 Demographic identifiers were participants' postgraduate year (PGY-1 to PGY-6), their department, and the site of their undergraduate medical education (University of Louisville School of Medicine, elsewhere in the United States, or abroad). We included residents' training locations because we have found useful data on differences in residents' knowledge and perceptions in previous studies.7

We e-mailed all 600 residents and fellows at ULSM in 2009 applying Dillman's tailored approach to online surveys. We followed up with 2 reminder e-mails 2 weeks apart and achieved a response rate of 24% (144 of 600).

Frequencies and percentages were used to summarize the demographic data (questions 1–3). Likert-scale data (questions 4–17) were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test to look for significant differences in responses between residents who completed medical school in the United States, and those educated abroad. A Bonferroni correction was placed on the traditional α level of P ≤ 0.05 to address inflated type 1 errors that might occur because of multiple testing of the 14 items. Using a Bonferroni correction, P ≤ 0.004 was equated to a 95% significance level.9 Knowledge quiz scores (questions 18–22) were analyzed first by calculating correct replies and then using the χ2 test for linear trend to assess whether a linear association existed between the percentage of correct responses and the year of residency; statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.01. Open-ended replies were analyzed using Pandit's variation of the Glaser and Strauss Constant Comparison method.10

Results

Demographics

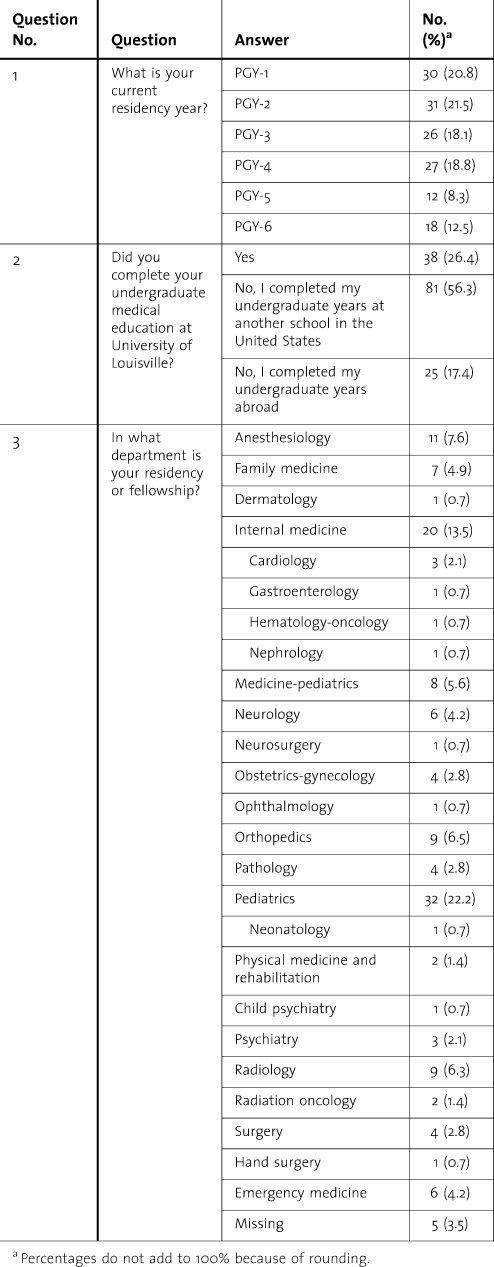

Twenty-four percent of the residents (144 of 600) responded to the survey (95% confidence interval, margin of error, 7.1). The proportions of graduates from US medical schools (USMGs) and graduates from international medical schools (IMGs) in the survey population were similar to the actual population of residents. The proportions of respondents by department also mirrored our actual resident distribution, with our 2 largest departments—pediatrics and internal medicine—representing 22.2% and 13.5% of respondents, respectively (table 1).

TABLE 1.

Respondent Demographics

Perceptions and Attitudes

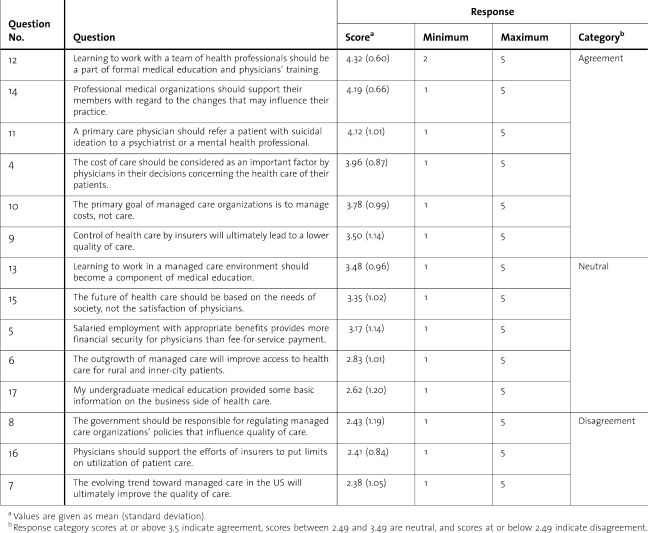

For the 14 perception and attitude questions, we categorized total mean responses into 3 groups: scores between 2.49 and 3.49 were neutral, scores at or above 3.5 indicated agreement, and scores at or below 2.49 indicated disagreement (table 2; figure 1).

TABLE 2.

Rank Order of the Perception Questions on a 5-Point, Likert-Style Agreement Scale

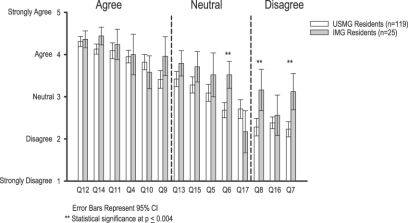

FIGURE 1.

Total Mean Responses by Question and Undergraduate Medical School Location

Residents agreed with statements relating to the importance of learning to work as a team (question 12), the need for professional organizations to support their members in their practices (question 14), the right of physicians to retain referral powers (question 11); the primary goal of managed care organization seeming to be managing costs, not providing care (question 10), the cost of care needing to be considered an important factor in decisions concerning the health care of their patients (question 4), and the control of health care by insurers ultimately leading to a lower quality of care (question 9).

Residents were generally neutral regarding the following: medical education should have a component on learning to work in a managed care environment (question 13), the future of health care should be based on the needs of society rather than the satisfaction of physicians (question 15), salaried employment with appropriate benefits provides more financial security than fee-for-service payment (question 5), the outgrowth of managed care will improve access to health care for rural and urban patients (question 6), and their undergraduate medical education provided some basic information on the business side of health care (question 17).

Responses to question 6 showed a statistically significant difference (P ≤ .004) between USMGs and IMGs, with IMG residents more likely to agree that the outgrowth of managed care would improve access to health care for rural and urban patients.

The 3 questions with which residents' disagreed were that the government should be responsible for regulating managed care organizations' policies that include quality of care (question 8); that physicians should support the efforts of insurers to put limits on patients' use of medical care (question 16); and that the evolving trend toward managed care in the United States would ultimately improve the quality of care (question 7). Replies to questions 7 and 8 both showed statistically significant differences (P ≤ .017) between USMGs and IMGs.

Knowledge

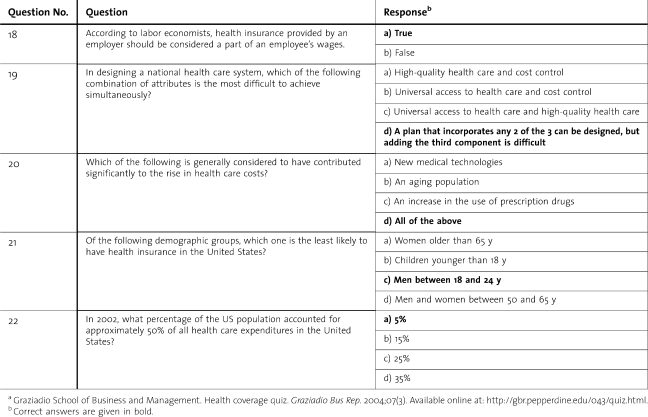

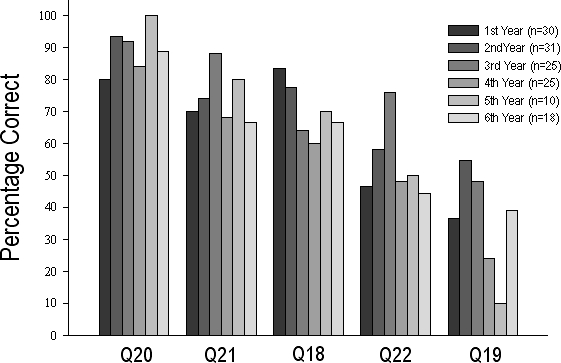

On the 5 health care cost questions, residents did well on questions 20 and 21 but were less accurate on questions 18, 19, and 22 (table 3; figure 2). Interestingly, there were no consistent differences among or between groups by PGY or department. Although there was a slight decrease in scores on several questions with increasing PGY, there was no statistically significant linear trend in scores by PGY.

TABLE 3.

Knowledge Quiz Questions and Correct Answersa

FIGURE 2.

Percentage of Correct Replies on Knowledge Quiz by Postgraduate Year

Q18–Q22, questions 18 through 22.

Qualitative Outcomes

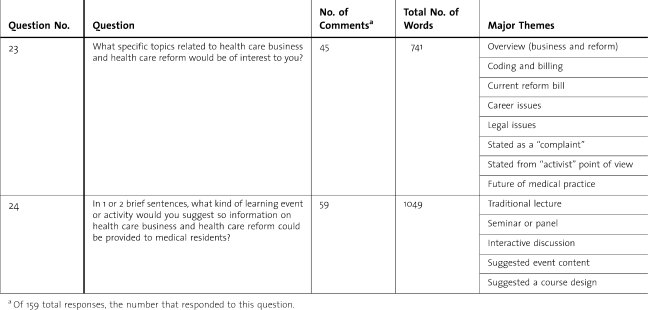

Thirty-seven percent responded to at least 1 of the 2 open-ended questions (table 4). Examples of suggestions for content (question 23) included: understanding the inner workings of the system as it is now as a basis for understanding changes; and teaching free market solutions to health care reform, increasing competition among insurers by selling insurance across state lines, tort reform, pooling small businesses into larger groups for greater discounts on insurance premiums, greater use of generic drugs to lower prescription costs, and triaging patients in emergency departments.

TABLE 4.

Qualitative Data Summary

In response to question 24, “What kind of learning event or activity do you suggest (for health care business content)?” one participant suggested that “we should have experts on health care systems in places such as Massachusetts, Canada, and Britain discuss the pros and cons, and similarities and differences.”

Discussion

Quality

In this category, the overall trend was a lack of confidence in either government or other managed care systems to oversee the quality of care and neutrality toward the idea that improved access will occur when government or managed care systems take more control. This corresponded with results found by Hojat et al.2 The differences in responses to questions 6 and 8 between IMGs and USMGs suggest that internationally trained residents think that managed care, government regulation of managed care, and the growth of managed care can be positive. It may be that this group has had more opportunities to see other systems in action rather than just hearing media accounts and political rhetoric.

Financial

Residents agreed that cost should be considered an important factor by physicians in their decisions concerning the health care of their patients. This suggests that residents are aware that prescribing medications, therapies, or tests that a patient cannot afford can be problematic. The residents had a neutral opinion on whether salaried employment with appropriate benefits provides more financial security to the physician than does fee-for-service. This may be because our residents receive a set stipend and have not experienced other systems of compensation.

Referral

Most of the residents agreed with question 11, “A primary care physician should refer a patient with suicidal ideation to a mental health professional,” but disagreed with question 16, “Physicians should support the efforts of insurers to put limits on use of patient care.” These findings suggest that residents prefer that physicians be in charge of patient care rather than insurers. Residents may see themselves as good “gatekeepers” because they are already considering the cost of care in relation to the patients (question 4), as opposed to managed care organizations who manage cost and, presumably, not care (question 10). Similar to the results on financial questions, this finding may be because residents in Kentucky have little experience with classic “managed care” systems.

Education

Most residents responded that learning to work with a team of health professionals should be a part of medical education. However, they were neutral on the importance of learning to work in a managed care environment. This may be because residents at our institution have limited exposure to managed care environments or because they have a lack of support for managed care in general (ie, outcomes of questions 6, 9, and 10). The low-neutral score for question 17—“My undergraduate medical education provided some basic information of the business side of healthcare”—supports the need for instruction in the business of health care.

Other

Residents agreed that a professional medical organization should support its members but were neutral about whether the future of health care should be based on the needs of society rather than the satisfaction of physicians, which corresponds to the findings by Hojat et al.2 Our residents know society's needs matter, but we can deduce from their replies to several survey questions that they have little confidence in a positive future for health care if physician views are excluded.

Knowledge

The responses to the knowledge questions show a wide and inconsistent range of knowledge throughout departments and PGY levels. One would expect an increase in knowledge of the business of health care as residents progress through their training, but we found none. On some questions, scores actually decreased with increasing PGYs. Although the residents are working in a medical environment and learning the practice of medicine, they are not learning the business of medicine.

Qualitative Outcomes

Question 23 asked, “What specific topics related to health care business and health care reform would be of interest to you?” Residents requested education in the areas of the business of medicine and reform, coding and billing, current reform bills, career issues, legal issues, and the future of medical practice. In addition, some statements were expressed from an “advocate/reform” point of view, and a few answers were stated as complaints. Learners who are able to articulate what they do not know are much more likely to succeed in a curriculum designed to address that lack of knowledge.11

The responses to question 24—“In one or two brief sentences, what kind of learning event or activity would you suggest so information on health care business and health care reform could be provided to medical residents?”—included traditional lectures, seminars or panels, and interactive discussions. We know from previous program evaluations that residents enjoy off-site and multidisciplinary events.7

Limitations

This study had several limitations: As with most web-based surveys, participants were self-selected; the response rate was slightly less than 25%; approximately 15% of respondents did not complete the baseline-knowledge quiz; and approximately 9% of respondents failed to provide the location of their training.

Call for Future Research

Although this study was conducted at 1 institution in Kentucky, results from many of the perception and attitude questions mirrored the findings in the Hojat et al2 study at Jefferson Medical College in Pennsylvania. Therefore, we think many of the results would likely be replicated at other institutions. However, a multi-institutional design covering different geographic areas in the United States might be able to identify potential regional differences, especially for managed-care questions, where regional differences affect residents' exposure to various health care systems.

Conclusions

This needs assessment and content analysis was the first step toward the development of a graduate medical education curriculum for health care business and health care cost. Although our results indicate that residents as a group may have an overall distrust of managed care and government relation to care, our role as educators is to teach residents to function in the system, not to offer philosophically biased training toward new systems. System-based practice, as defined in the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education core competencies, states that residents must demonstrate an awareness of, and responsiveness to, the larger context and system of health care and that they should be able to call effectively on system resources to provide optimal health care.12

Residents enter their residency training with different perceptions and knowledge about the business of health care and health care costs. They do not consistently acquire knowledge in these areas as part of their on-the-job training. They appear to be aware of their lack of knowledge and training and are open to instruction in those areas. Our needs assessment and content analysis is the beginning for a resident curriculum on health care business and health care cost. As the US health care system changes, we must also change to better meet the needs of residents so they can function in an increasingly complex system.

Footnotes

All authors are at University of Louisville School of Medicine. John L. Roberts, MD, is Associate Dean for Graduate Medical Education; Michael Ostapchuk, MD, MS Ed, is Assistant Dean for Graduate Medical Education; Karen Hughes Miller, PhD, is Assistant Professor in Graduate Medical Education Research; and Craig H. Ziegler, MA, is a Biostatistician in the Office of Medical Education at the University of Louisville School of Medicine.

Our sincere thanks to Nancy Dodd, Editor, Graziadio Business Report, Pepperdine University, for use of selected knowledge-base questions; Mohammadreza Hojat, PhD, Research Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Jefferson Medical College, for use of selected survey questions; and to participants at the April 25–28, 2010, Association of American Medical Colleges Group on Resident Affairs workshop—What Do Residents Already Know About Healthcare Reform and What Should We Be Teaching Them?—whose discussion helped us interpret our findings.

Funding: The authors report no external funding source.

References

- 1.Greenberger NJ, Davies NE, Maynard EP, Wallerstein RO, Hildreth EA, Clever LH. Universal access to healthcare in America: a moral and medical imperative. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112(9):637–639. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-9-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hojat M, Veloski JJ, Louis DZ, et al. Perceptions of medical school seniors of the current changes in the US health care system. Eval Health Prof. 1999;22(2):169–183. doi: 10.1177/01632789922034248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veloski JJ, Brazansky B, Nash DB, Bastacky S, Stevens DD. Medical student education in managed care settings: beyond HMOs. JAMA. 1996;276(9):667–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) 2009. Report to the Congress: improving incentives in the Medicare Program (Chapter 1) Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/Jun09_EntireReport.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rothwell WJ, Kazanas HC. Mastering the Instructional Design Process: A Systematic Approach. 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer; 2008. pp. 53–78. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graziadio School of Business and Management. Health coverage quiz. Graziadio Bus Rep. 2004;07(3) Available online at: http://gbr.pepperdine.edu/043/quiz.html. Accessed October 5, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostapchuk M, Patel P, Miller KH, Ziegler CH, Greenberg R, Haynes G. Improving residents' teaching skills: a program evaluation of residents as teachers course. Med Teach. 2010;32(2):e49–e56. doi: 10.3109/01421590903199726. Available at: http://informahealthcare.com/doi/pdf/10.3109/01421590903199726. Accessed April 1, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dillman DA. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. 2nd ed. New York, NY: J Wiley Co; 2000. pp. 165–170. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huck SW. Reading Statistics and Research. 4th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson, Allyn & Bacon; 2004. p. 501. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandit NR. The creation of theory: a recent application of the grounded theory method. Qual Rep. 1996;2(4) Available at: http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR2-4/pandit.html. Accessed April 1, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knowles MS, Holton EF, Swanson RA. The Adult Learner. 6th ed. Burlington, MA: Elsevier, Butterworth-Heinemann; 2006. pp. 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) ACGME Outcome Project—Educating Physicians for the 21st Century: Module 2, Practical Implementation of the Competencies. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/outcome/e-learn/e_powerpoint.asp. Accessed April 1, 2011. [Google Scholar]