Abstract

Background

Curricular redesign and introduction of the Chronic Care Model in our residency clinic during 2005–2007 achieved limited success in glycemic (glycated hemoglobin level [A1c]), lipid (low-density lipoprotein fraction [LDL]), and blood pressure (BP) control for patients with diabetes.

Intervention

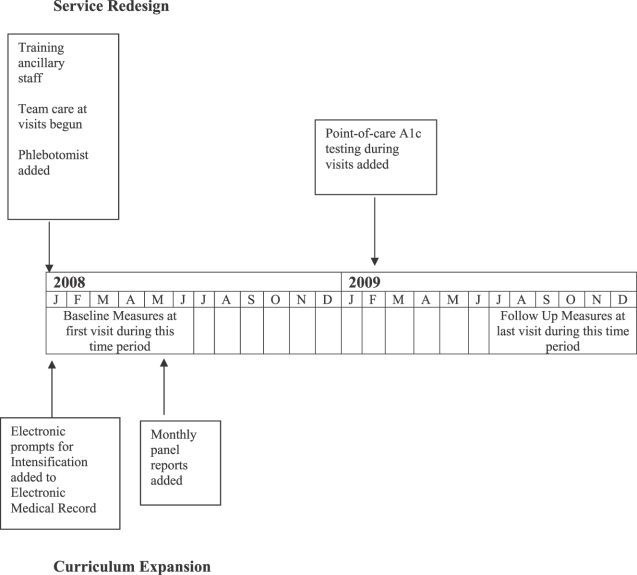

Beginning in January 2008, ancillary staff performed previsit, protocol-driven reviews of medical records of patients with diabetes to identify those not at A1c, LDL, and BP goals; inserted electronic prompts into the records regarding deficiencies; and obtained samples for A1c or lipid panel when needed. Faculty feedback regarding resident-specific panel reviews was added in May 2008, and point-of-care A1c testing was implemented in February 2009.

Methods

We conducted a 2-year retrospective study of all patients at our facility with diabetes mellitus, who had at least 1 visit during January to June 2008 (baseline) and 1 visit during July to December 2009 (follow-up). Measures included the most current A1c, LDL, and BP results. Paired outcome results were compared using the McNemar χ2 test.

Results

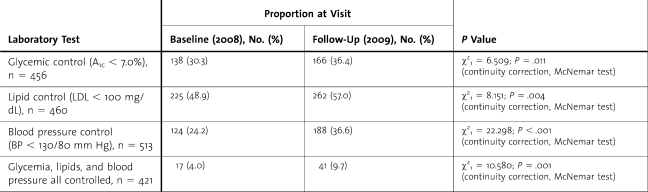

A total of 522 patients with diabetes mellitus were seen during the baseline and follow-up periods, and 456 patients (87.4%) had paired A1c results, with A1c < 7.0% for 138 of 456 patients (30.3%) at baseline and 166 of 456 patients (36.4%) at follow-up (P = .011). For LDL, 460 patients (88.1%) had paired results, with LDL < 100 mg/dL for 225 of 460 patients (48.9%) at baseline and 262 of 460 patients (57.0%) at follow-up (P = .004). A total of 513 patients (98.3%) had paired BP results in which the BP < 130/80 mm Hg for 124 of 513 patients (24.2%) at baseline and for 188 of 513 patients (36.6%) at follow-up (P < .001). There were 421 patients (80.7%) with paired results for all 3 measures, with 17 of 421 patients (4.0%) at goal at baseline and 41 of 421 patients (9.7%) at goal at follow-up (P = .001).

Conclusion

The interventions resulted in statistically significant improvements in the proportion of patients with diabetes who attained goal for A1c, LDL, and BP levels. Our redesign elements may be useful in enhancing resident education and in improving patient care.

Background

Evidence-based guidelines for care of patients with diabetes are well established,1,2 yet adherence is low.3–5 The Chronic Care Model (CCM) uses a multidisciplinary team6 to improve care processes and clinical outcomes for patients with chronic illnesses.7,8 Organizational and curricular changes in ambulatory care are needed to improve resident training in team-based models of care.9–11

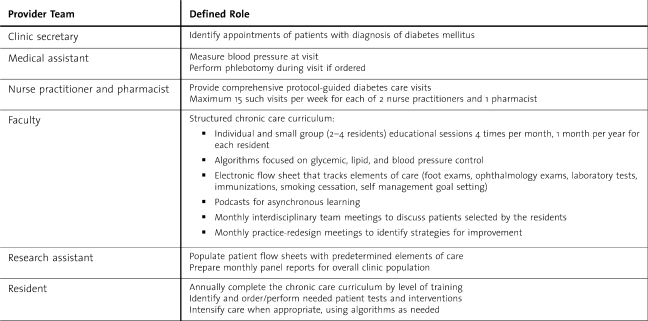

Our residency program was introduced to the CCM through participation in the Academic Chronic Care Collaborative12 in 2005–2006. Involvement in the Academic Chronic Care Collaborative was the impetus for the development of a structured curriculum for residents, for practice redesign with an expanded role for nonphysician staff, and for implementation of an electronic medical record and diabetes registry,13,14 (table 1a). After assessing the effectiveness of the program in 2006 with a sample of 150 patients, this model of care was applied to all patients with diabetes in our resident clinic as part of the Residency Review Committee–Internal Medicine's Educational Innovation Project. The intermediate clinical outcomes for glycated hemoglobin level (A1c), low-density lipoprotein fraction (LDL), and blood pressure (BP) were slow to improve. Small sample studies by residents in our program identified many missed opportunities to intensify treatment during clinic visits when patients were not at their goal. Lack of readily available decision support during visits, difficulty with accessing recent laboratory test results, and absence of cues related to abnormal results during all visits were identified as barriers to intensification of care.

TABLE 1a.

Care Delivery Redesign Elements Using the Chronic Care Model 2005–2007

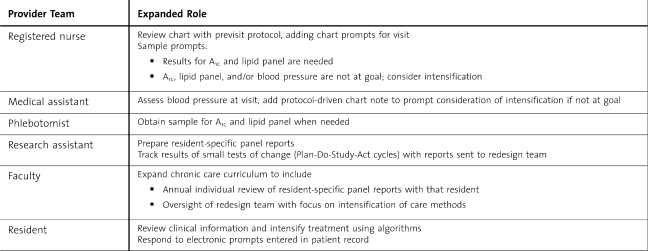

A series of interventions (shown in table 1b) were implemented in January 2008. The aim for those interventions was to increase the proportion of patients with diabetes who were at goal levels for A1c, LDL, and blood pressure and to expand the experience of residents in successful team-based patient care. The interventions expanded the role of care-delivery team members and applied that approach to all visits by patients with diabetes. The residency's chronic care curriculum was expanded to enhance residents' experiences with team care. In February 2009, point-of-care A1c testing was added to address inefficiencies caused by delayed reporting of results (table 1c). The flow diagram illustrated in Figure 1 provides a timeline of when each change was initiated.

TABLE 1b.

Team-Based Care for All Visits by Patients With Diabetes—Implemented January 2008

TABLE 1c.

Team-Based Care for All Visits by Patients With Diabetes—Implemented February 2009

FIGURE 1.

Timeline for Implementation of Interventions

Methods

Setting

The Internal Medicine Center is the continuity clinic for the internal medicine residency program at Summa Health System, a major teaching hospital of the Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine. The center provides care for approximately 7000 patients living in the greater Akron, Ohio, area and is staffed by 48 residents, 16 internal medicine faculty physicians, 2 nurse practitioners, and 1 pharmacist. Eleven faculty physicians have their own patient panels and typically see their patients no more than 1 half-day per week. The other 5 faculty members do not have their own patient panels and serve as preceptors in the center. Nurse practitioners and the pharmacist do not have their own patient panels but provide comprehensive diabetes visits, as well as acute and urgent visits for patients of the faculty and residents. Faculty physicians represented approximately 1 clinical full-time equivalent physician, and the 48 residents represented 9 clinical full-time equivalent physicians. Faculty and residents have patients with diabetes on their panels. Each resident provides continuity care for a panel of 100 to 200 patients during 3 years of training. A phlebotomist was assigned to the center in January 2008.

Study Design

A retrospective study design was used to assess the effectiveness of these interventions, measured by a statistically significant increase in the proportion of patients with A1c levels <7.0%, LDL fractions <100 mg/dL, or BP <130/80 mm Hg after implementation. Summa Health System's Institutional Review Board designated the project as quality improvement and exempted it from review.

Patient Population

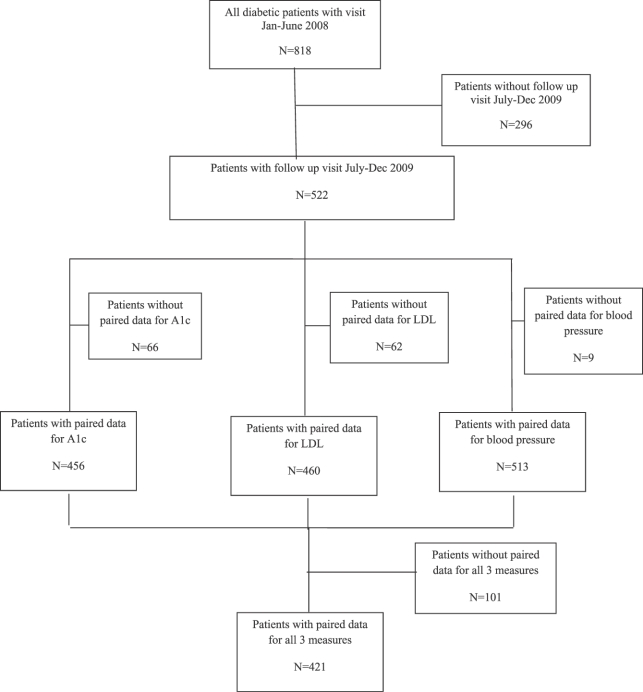

The study sample included all patients seen in the Internal Medicine Center during January to June 2008 (baseline visit) with a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (codes 250.xx, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision) who also had at least 1 visit during July to December 2009 (follow-up visit). All visits with a faculty physician, resident, nurse practitioner, or pharmacist were considered for inclusion, with 87% of the patients having a resident physician. There were 818 patients with diabetes who had at least 1 visit to the resident clinic during the baseline period, and 522 of these (63.8%) returned during the follow-up period (figure 1). The 522 patients included in the sample had 4877 visits during 2008–2009 for an average of 4.7 visits per patient per year. Patient measures at the first visit during the baseline period were designated baseline. Patient measures at the last visit during the follow-up period were designated follow-up. Baseline measures for A1c, LDL, and BP were analyzed for the 296 patients excluded from the sample because they did not have a follow-up visit in the specified time period in 2009 to determine whether this exclusion introduced bias. No major differences were found. Mean A1c levels and LDL fractions were nearly identical. Mean systolic and diastolic BP were slightly lower in patients with no follow-up visit.

Measures

The target goals for glycemic, lipid, and blood pressure control were based on the American Diabetes Association standards at the beginning of our study.1 Glycemic control was defined as an A1c < 7.0%. Baseline and follow-up A1c values were determined as the most recent result obtained between 6 months before and 1 month after the visits. Lipid control was defined as an LDL < 100 mg/dL. Baseline and follow-up LDL values were determined as those obtained between 1 year before and 1 month after the visits. Hypertension control was defined as a BP < 130/80 mm Hg. Baseline and follow-up BP values were those obtained during visits. A standard chart-review template was used to collect relevant visit-specific laboratory values from the electronic medical record. The A1c and LDL testing were performed by the hospital laboratory or other national laboratories, except for the point-of-care A1c testing, which began in February 2009. Point-of-care A1c levels were measured using a Siemens DCA Vantage analyzer (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Deerfield, IL), which is correlated to high-performance liquid chromatography testing and has been deemed to have traceability to the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial reference method.15 We used the external proficiency testing program of the American Academy of Family Physicians Proficiency Testing program for office laboratories and used controls with each lot number and shipment of reagents.

Analysis

Proportions of patients achieving glycemic, lipid, and blood pressure control at baseline and follow-up were compared to assess improvements. Each outcome (A1c, LDL, and BP) was analyzed separately, and all patients with complete data for baseline and follow-up in an individual outcome were included in the analysis. Figure 2 shows the distribution of patients included in the study and the number of patients included for analysis in each outcome. The SPSS version 17 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL), nonparametric, 2-related samples McNemar test was used to complete the analysis. The continuity-corrected χ2 is reported with an α level of .05 established for significance testing.

Results

Course of the Intervention

Our quality-improvement strategy involved rapid cycles of change. Ancillary staff training took place during a 30-minute group session. The electronic medical record and registry were used to prepare reports of monthly outcomes for all members of the patient-care team. Problems with process and outcomes were discussed by the interdisciplinary redesign team, which initiated further changes to increase the effectiveness of the intervention.

FIGURE 2.

Description of Sample Selection for Outcomes Analysis

Sample Characteristics

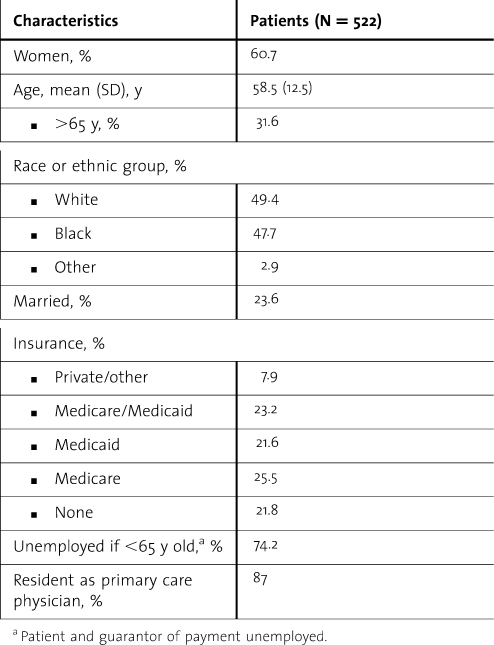

Table 2 provides a description of the characteristics of the 522 patients included in the sample. The average age was 58.5 years, and 60.7% were women. Blacks and non-Hispanic whites were equally represented. Although most patients were covered by Medicare or Medicaid, 21.8% (114 of 522) had no insurance, and 74.2% of the patients younger than 65 years were not employed nor was the guarantor of payment for the patient's medical bill employed.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of Patients in the Sample

Outcomes

Table 3 provides an overview of the changes in glycemic, lipid, and blood pressure control from baseline to follow-up. The proportion of patients with A1c < 7.0% increased from 30.3% at baseline to 36.4% at follow-up (P = .011). The proportion with LDL < 100 mg/dL increased from 48.9% at baseline to 57.0% at follow-up (P = .004), and the proportion with BP < 130/80 mm Hg increased from 24.2% at baseline to 36.6% at follow-up (P < .001). At follow-up, 9.7% of the patients were at goal for all 3 measures, compared with 4.0% at baseline (P = .001).

TABLE 3.

Proportions of Patients at Goal for Glycemic (Glycated Hemoglobin Level [A1c]), Lipid (Low-Density Lipoprotein Fraction [LDL]), and Blood Pressure (BP) Control

Discussion

After implementation of our interventions, we were able to document statistically significant improvement in outcomes for glycemic, lipid, and blood pressure control in a sample of patients with diabetes receiving care in our resident clinic. The interventions included (1) team changes, with staff reviewing, prior to the visit, the electronic medical records for all patients with diabetes to determine whether they had achieved the nationally recognized goals for A1c, LDL, and BP; (2) addition of electronic prompts in the electronic medical record for patients not at goal; (3) additional laboratory support, including the introduction of point-of-care A1c testing during visits; and (4) expansion of the chronic care educational curriculum by adding faculty review of resident-specific panel reports to reinforce the use of treatment-intensification algorithms.

Successful application of the Chronic Care Model to all patients with diabetes in our resident clinic resulted in a training paradigm using measured quality outcomes and evidence-based medicine to drive care system improvements. The greatest challenge during this process was a general resistance to change. We overcame this by engaging all team members in the redesign process and providing the entire team with feedback regarding changes in measured processes of care and patient outcomes. The availability of data from small tests of change helped us to select those service-redesign options most likely to have a positive effect when applied to the entire clinic. This information, particularly the resident-specific panel data, helped to achieve buy-in from residents and faculty who were skeptical of the benefits of the new model. Resident involvement has been identified by others as being critical to the success of redesigns in residency clinic practice.16 We felt resident involvement was particularly important in the redesign because of their intimate knowledge of the workings of the resident clinic and the importance of providing future physicians with the best possible training to allow them to provide optimal care throughout their careers.

Although there was a statistically significant improvement in the number of patients achieving A1c, LDL and BP goals, the percentage of patients reaching all 3 targets was relatively low (9.7%). This finding is lower than the national average of 12.2% estimated by the most recent study published on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey,17 possibly because of differences in the socioeconomic status of our patients and those in the national sample. Reports,3,16,18 from settings similar to ours have demonstrated 6.6% to 17.1% of patients reaching targets for all 3 outcomes. Future efforts in our clinic will focus on intensification of care for patients who have successfully reached one target, which may be one way to improve overall clinical outcomes.

Our study has some limitations, including its single-site design. At the same time, the redesign Plan-Do-Study-Act methodology we used was developed from our work with the Academic Chronic Care Collaborative and has been used to introduce change at other academic medical centers.8,19 Because several interventions were implemented concurrently, we cannot be certain which one(s) had the greatest effect. Without a control group, other factors (such as lifestyle counseling and medication adherence) could have been responsible for the changes observed, and with a single-group design, regression to the mean could have influenced our results. Our study only included those patients with diabetes who had at least one visit during the first half of 2008 and at least one visit during the second half of 2009, which increases the probability that less-adherent patients were excluded from analysis. Despite these limitations, our resident clinic redesign has demonstrated that statistically significant improvements in A1c, LDL, and BP control can be achieved by patients with diabetes in a setting in which it is challenging to realize goals for improvement.20 This quality improvement initiative also provided opportunities for engaging residents in outcomes-driven practice redesign at an experiential level. The relatively simple changes in care delivery may be transferrable to other residency clinics and may serve to improve outcomes for future patients of our graduates. Future research should confirm our findings through the use of a matched control group or a randomized, controlled trial design to reduce the possible influence of external factors. Future studies could also focus on improving the rate of follow-up and on patient satisfaction, which could have a positive influence on follow-up and adherence to care.

Footnotes

All authors are at Summa Health System and Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine. James K. Salem, MD, is Endocrinology Service Chief; Ronald R. Jones, MD, Internal Medicine Core Faculty; David B. Sweet, MD, is Program Director in Internal Medicine Residency; Sana Hasan, DO, is a Resident in Internal Medicine; Hope Torregosa-Arcay, MD, was a Resident in Internal Medicine and is currently a Fellow in Geriatrics at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation; and Lynn Clough, PhD, is Internal Medicine Program Administrator.

Funding: The authors disclose no external funding source.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(suppl 1):S4–S41. doi: 10.2337/dc07-S004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodbard H, Blonde L, Braithwaite S, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for the management of diabetes mellitus. Endocr Pract. 2007;13(suppl 1):3–68. doi: 10.4158/EP.13.S1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant R, Buse J, Meigs J for the University HealthSystem Consortium Diabetes Benchmarking Project Team. Quality of diabetes care in U.S. academic medical centers: low rates of medical regimen change. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(2):337–442. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.2.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saaddine J, Cadwell B, Gregg E, et al. Improvements in diabetes processes of care and intermediate outcomes: United States, 1988–2002. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(7):465–474. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-7-200604040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saaddine J, Engelgau M, Beckles G, Gregg E, Thompson T, Narayan V. A diabetes report care for the United States: Quality of care in the 1990s. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(8):565–574. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-8-200204160-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner E, Austin B, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20(6):64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodenheimer T, Wagner E, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, part 2. JAMA. 2002;288(15):1909–1914. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coleman K, Austin B, Branch C, Wagner E. Evidence on the chronic care model in the new millennium. Health Aff. 2009;28(1):75–85. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiPiero A, Dorr D, Kelso C, Bowen J. Integrating systematic chronic care for diabetes into an academic internal medicine resident-faculty practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;223(11):1749–1756. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0751-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevens D, Sixta C, Wagner E, Bowen J. The evidence is at hand for improving care in settings where residents train. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;223(7):1116–1117. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0674-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warm E, Schauer D, Diers T, et al. The ambulatory long-block: an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Educational Innovations Project (EIP) J Gen Intern Med. 2008;223(7):921–926. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0588-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevens D, Wagner E. Transform residency training in chronic illness care—now. Acad Med. 2006;81(8):685–687. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200608000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boville D, Saran M, Salem J, et al. An innovative role for nurse practitioners in managing chronic disease. Nurs Econ. 2007;25(6):359–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones R, Sweet D, Radwany S, Clough L, Zarconi J. Redesigning care for chronic disease: Using clinical outcomes to drive curriculum and patient care in a residency based clinic. ACGME Bull. August 2007:18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program. List of NGSP certified methods (updated 9/10, listed by date certified) Available at: http://www.ngsp.org/docs/methods.pdf. Accessed September 17, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu G, Beresford R. Implementation of a chronic illness model for diabetes care in a family medicine residency program. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(suppl 4):615–619. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1431-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheung B, Ong K, Cherny S, Sham P, Tso A, Lam K. Diabetes prevalence and therapeutic target achievement in the Unites States, 1999–2006. Am J Med. 2009;122(5):443–453. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masterson E, Patel P, Kuo Y, Francis C. Quality of cardiovascular care in an internal medicine resident clinic. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(3):467–473. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00030.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevens D, Bowen J, Johnson J, et al. A multi-institutional quality improvement initiative to transform education for chronic illness care in resident continuity practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(suppl 4):574–580. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1392-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chin M, Cook S, Drum M, et al. Improving diabetes care in Midwest community health centers with the health disparities collaborative. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(1):2–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]