Abstract

Purpose

A design conference with participants from accredited programs and institutions was used to explore how the principles of patient- and family-centered care (PFCC) can be implemented in settings where residents learn and participate in care, as well as identify barriers to PFCC and simple strategies for overcoming them.

Approach

In September 2009, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) held a conference with 74 participants representing a diverse range of educational settings and a group of expert presenters and facilitators. Small group sessions explored the status of PFCC in teaching settings, barriers that need to be overcome in some settings, simple approaches, and the value of a national program and ACGME support.

Findings

Participants shared information on the state of their PFCC initiatives, as well as barriers to implementing PFCC in the learning environment. These emerged in 6 areas: culture, the physical environment, people, time and other constraints, skills and capabilities, and teaching and assessment, as well as simple strategies to help overcome these barriers. Two Ishikawa (Fishbone) diagrams (one for barriers and one for simple strategies) make it possible to select strategies for overcoming particular barriers.

Conclusions

A group of participants with a diversity of approaches to incorporating PFCC into the learning environment agreed that respectful communication with patients/families needs to be learned, supported, and continuously demanded of residents. In addition, for PFCC to be sustainable, it has to be a fundamental expectation for resident learning and attainment of competence. Participants concurred that improving the environment for patients concurrently improves the environment for learners.

Editor's Note: The ACGME News and Views section of JGME includes data reports, updates, and perspectives from the ACGME and its review committees. The decision to publish the article is made by the ACGME.

Medicine has increased its scientific and technologic sophistication and capabilities. At the same time, patients and families report the environment of care in teaching hospitals is sometimes sterile and lacking in human interaction, is on occasion frightening, and often does not allow them to be heard and have input into care decisions. Six years after the Institute of Medicine's report Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century made patient-centeredness one of “the aims for improvement”1 for the health care system, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) adopted communication and interpersonal skills as 1 of 6 competencies,2 the ACGME established a Patient- and Family-Centered Care (PFCC) Advisory Group. The advisory group comprised members of the ACGME Board of Directors, experts in PFCC, medical educators, and residents. It was charged with exploring patient- and family-centered care and its effects on the learning and clinical experience of residents and fellows. The group met in 2 invitational roundtable sessions and identified key issues and trends in PFCC and their relevance to resident education. The group also was charged with planning a “design conference” that would blend didactic and design sessions to introduce a larger group of participants to PFCC and collect their ideas for practical initiatives to incorporate these principles into resident education in their local settings.

The Design Conference

In September 2009, 74 individuals, 13 speakers, and ACGME staff participated in a 2-day Design Conference. Participants represented a variety of teaching institutions and individuals engaged with graduate medical education (GME) at the program and institutional levels. The interactive design allowed attendees to explore the benefits of PFCC, share examples from their programs and institutions, discuss barriers to implementation of PFCC in teaching settings, and suggest initiatives with a high likelihood of success for incorporating PFCC in teaching settings. In addition to highlighting key elements of the didactic sessions, this article summarizes: (1) information on the status of PFCC in participating programs and institutions; (2) barriers to PFCC in the current GME environment; (3) simple and more far-reaching approaches for actively engaging residents in PFCC; and (4) suggestions for efforts at the national level to incorporate PFCC into residency curricula, teaching, and assessment.

Didactic Sessions

Presentations by a number of experts set the stage for the design sessions. After opening remarks by advisory group co-chairs Deborah Powell, MD, and Carl Patow, MD, Daniel Shin, MD, of the Palo Alto Medical Foundation, recounted his personal experience with a serious illness. He described a stay in the intensive care unit, noting it profoundly influenced his thinking on the practice and profession of medicine. He emphasized the serious impact of illness on the individual, the often frightening nature of aspects of the health care experience for even sophisticated patients, and the importance of having the family be part of the care team.

Rosemary Gibson, MSc, senior program officer of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and Beverly Johnson, president and CEO of the Institute for Family-Centered Care, discussed strategies that support a change in culture from one that views families as visitors to one that encourages them to have an active role in patients' care. Patricia Sodomka, MHA, FACHE, senior vice president of patient- and family-centered care at the Medical College of Georgia Health, discussed how her institution considers PFCC a viable model in today's health care environment. She described patient advisory panels comprising adult and pediatric patients who have transformed patient care and how this, in turn, has influenced resident education and the ongoing professional development of faculty and other health professionals. Juliette Schlucter, project consultant and family leader at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, discussed the hospital's 15-year commitment to family-centered care.

Presentations by educators focused on program components that promote an environment that is patient centered as well as conducive to resident learning. Javier Gonzalez del Rey, MD, MEd, pediatric residency program director at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, shared his experience with family-centered bedside rounds and the positive effects for families and residents, and Peter Buckley, MD, professor and chair of psychiatry at the Medical College of Georgia, discussed patient and family engagement in adult settings. Mitzi Williams, MD, neurology resident at the Medical College of Georgia, talked about her experience of being involved with a PFCC initiative for neurology patients and the transformative effect it had on her understanding of patients and their needs. All presentations emphasized how PFCC generates culture change that transforms patient care settings. This included involvement of patient and family advisors in staff selection and staff development, as well as their input into the educational programs. The discussion that followed noted that PFCC seems to be more easily implemented in pediatrics settings and others with a high degree of existing family involvement, and that there may be barriers in adult and ambulatory care settings.

Paul Schyve, MD, senior vice president of The Joint Commission, and Kathy Vermoch, MPH, project manager for operations improvement, University HealthSystem Consortium, spoke about their organizations' PFCC initiatives. The final presentation focused on support for providers. Susan Fleischman, MD, vice president of Medicaid for the Kaiser Foundation Health Plan and Kaiser Foundation Hospitals, spoke about the physician's transformation from learner to patient advocate, and the support providers need for the difficult and frequently emotionally challenging task of caring for patients and families.

Design Sessions

The design sessions engaged participants in 3 structured exercises that collected information on current program and institutional efforts to introduce PFCC into resident education, sought consensus on barriers to PFCC, and elicited pragmatic approaches with a high likelihood of success in effectively designing and implementing PFCC in GME programs. The final session also discussed next steps to promote PFCC at the local, institutional, and national levels.

The summary presented in this paper provides aggregated results of the design sessions, focusing on common themes. The text from flip charts, design teams' team notes, and qualitative surveys sent to participants before and after the conference were aggregated using grounded theory, an inductive approach for interpreting qualitative data that allows themes and ideas to arise from open text.3

Current Status of PFCC at Participating Teaching Institutions

The first sessions asked participants about the status of PFCC initiatives at programs and institutions in the fall of 2009, and the extent to which these actively involved residents and linked to resident education goals. Participants represented a wide range of specialties and types of teaching institutions, with wide variation in their current implementation of PFCC and the degree of resident involvement. More than one-half reported their institution had embarked on a process to implement PFCC in their patient care enterprise, with some efforts spanning both inpatient and ambulatory settings. Common initiatives included education of patient care staff and patient surveys about the patient-centered nature of the care environment. Several respondents reported their PFCC initiative had input from a patient advisory committee.

A few participants reported their hospital-wide PFCC initiatives had enjoyed relatively limited success to date. Institutions that collected patient satisfaction data reported they had not seen much of a positive impact, with the exception being performance on the required Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting scores for Communication with Nurses and Doctors.4 Six participants reported their organization had conducted a self-assessment inventory using a tool developed by the Institute for Family-Centered Care,5 and 7 reported their institution had appointed patient advisory councils in one or more clinical areas. Nine participants noted that care in their institution or program is inherently patient centered, with education about and promotion of PFCC in each department, without there being a “formal” PFCC initiative that follows national guidelines:

There is education, training, and promotion of PFCC in each department, but this tends to be specialty specific. The physician (or resident) isn't always the only healthcare provider of PFCC, but they are generally responsible for seeing that it occurs, either by themselves or involving social workers, psychologists and nursing staff. Family issues are often part of the complex mix of problems addressed while a patient is hospitalized, and involves clarification of the family-patient interactions.

Although the “homegrown” PFCC in these settings reportedly was often specialty specific, it may involve a multidisciplinary team. Several participants indicated that their institutions lag behind their clinical departments in implementing PFCC, with departments making improvements that included allowing family members to room in, and having patient representation on clinical advisory and improvement groups.

A number of participants admitted to confusion between PFCC, the “patient-centered medical home” concept in internal medicine, family medicine, and pediatrics, and related initiatives, such as group visits that may include the family for patients with chronic conditions like diabetes or asthma.

Residents' Education About and Involvement in PFCC

The number of attendees with a functioning initiative to include residents in a PFCC effort or introduce them to the principles and practices of PFCC was much smaller, encompassing about one-fourth of participating institutions and programs.

Representatives were divided on the issue of whether the practice of PFCC was more widely disseminated in the inpatient versus the ambulatory setting. All agreed that the specialties with the largest representation in PFCC efforts and the greatest degree of resident involvement in PFCC were the primary care specialties, particularly family medicine and pediatrics. Resident involvement in PFCC also was prevalent in obstetrics and oncology units, albeit to a lesser degree.

Six participants reported on the use of team bedside rounds that include patients, families, residents, faculty, and other members of the health care team. During open discussion, participants emphasized that defining family and family desires for involvement in care may be rooted in education level, culture and language, health literacy, and prior experiences, and efforts to implement PFCC need to be tailored to suit patients' and families' needs. In addition, the term family may have a broad definition.

Several institutions with PFCC initiatives that did not have resident involvement noted the conditions for resident engagement are present, but to date no one has “connected the dots.” Participants also reported that clinical and GME leaders assign a lower priority to PFCC than to interventions that enhance electronic medical record capabilities, provision of evidence-based care, and efforts to improve programs for ambulatory management of chronic diseases.

Educational programs described by participants included hospital-wide initiatives that often entailed a few lectures that addressed basic principles, without reinforcement at the bedside:

Hospital-wide initiative to encourage residents to listen to patients, explain medications and procedures, anticipate discharge, exceed patient expectations and respect patients.

In other settings residents learn and participate in services that embrace PFCC principles in the delivery of care. Participants commented that selected medical students entering residency have been exposed to an organized PFCC curriculum, but concepts learned tend to decay when they are not nurtured by the GME environment. Several participants commented on the challenge of embedding PFCC in the educational curriculum and in assessment tools, noting the distribution across multiple competencies, including communication and interpersonal skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice. Several participants noted that patients are an important resource in teaching and introducing residents to PFCC:

…one thing that works is that patients and families are eager to help. They willingly participate despite numerous obstacles. Many have expertise in systems and have new creative ideas. What is difficult is the need to change the practices of many physicians.

Barriers to and Simple and More Far-Reaching Strategies for Incorporating PFCC in the Resident Learning Environment

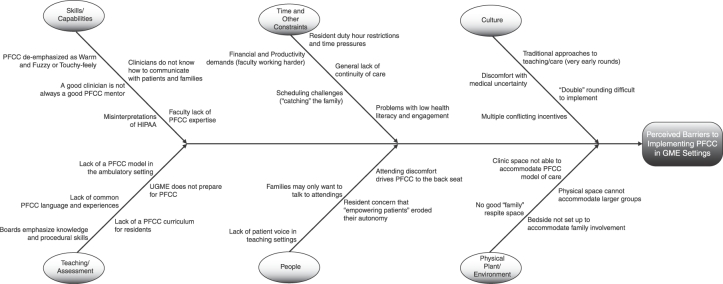

The focus of the second design session was barriers to implementing PFCC in the learning environment. Aggregation of the individual items showed these related to 6 areas: culture, the physical environment, people, time and other constraints, skills and capabilities, and teaching and assessment. The aggregated information on barriers to PFCC is shown as an Ishikawa (Fishbone) diagram (figure 1).6 This makes it possible to highlight the groups of factors that present barriers to PFCC in the learning environment.

FIGURE 1.

Barriers to PFCC in the GME Environment

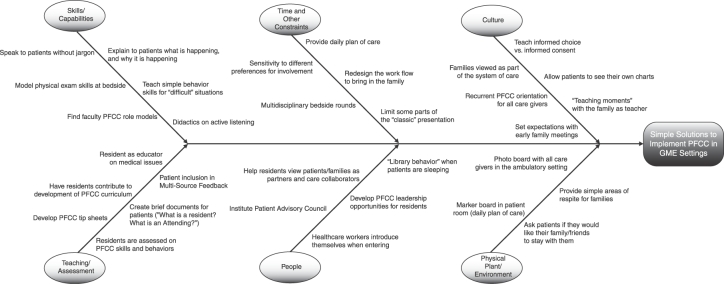

In the third exercise, participants suggested strategies for implementing PFCC in the learning environment, focusing on simple strategies with a high likelihood of success. The aggregated responses also are presented as an Ishikawa diagram showing the same domains as the aggregation of the information on barriers (figure 2). This allows the reader to see how the simple approaches can be used to overcome a barrier that has been identified in the local program or institutional learning environment. For example, given the limited time for bedside rounding, addressing the concepts of patient- and family-centered care during rounds could be achieved by limiting some parts of the “classic” format for presenting patients on rounds. In implementing PFCC at the institutional level, simple strategies proposed included starting with services with more existing family involvement, such as pediatrics, critical care, geriatrics, and palliative care.

FIGURE 2.

Simple Solutions to Incorporate PFCC Principles in the GME Environment

During the discussion about conditions that allow PFCC to emerge, participants stressed that respectful communication with patients/families needs to be learned, supported, and continuously demanded. When classroom or didactic sessions are sporadic and not integrated at the bedside, adoption of the principles and sustained change are seriously compromised. This suggests the most important consideration is how well PFCC concepts and behaviors are embedded in day-to-day patient care and teaching.

Participants also suggested more comprehensive and involved strategies for implementing PFCC. Most require greater institutional commitment to PFCC. Some concepts were considered far-reaching, not because of the financial commitments but because of the significant conceptual shifts that are required. They include giving families the power to “dismiss” a resident (not allow him or her to participate in the patient's care) if the individual does not provide patient- and family-centered care. Another entailed the participation of a family member on residency committees, including resident selection and evaluation, and on the institutional GME committee. A third approach involved having residents become “patients” and share the patients' experiences, potentially accompanied by reflection and writing.

To address the inadequate physical environment, participants suggested larger redesign efforts with patient input and family input. Changes in the culture domain would entail patient journals being kept as part of the medical record and eliminating the concept of visiting hours, giving families continuous access to patients. Related to GME curricula, more far-reaching approaches could include individualized learning plans related to PFCC.

“Next Steps” for Advancing PFCC in Resident Education

During the final exercise the design teams discussed “next steps.” Participants emphasized the benefit of small practical steps, such as continuing local conversations and efforts to implement PFCC. Suggestions include residents telling stories about their experience with patients for a national collection of recordings similar to the StoryCorps recordings presented periodically on National Public Radio. Attendees also commented on the need for a national strategy for incorporating PFCC into residency curricula and an ongoing role for the ACGME. One recommendation was to add information about PFCC education for residents on the ACGME website. Added suggestions for an expanded role for ACGME included development of an assessment tool to measure the effectiveness of different models of teaching PFCC. Participants commented on the value of institutional PFCC self-assessment tools, and suggested that some of these could be developed or adapted. Another recommendation called for ACGME to partner with other organizations in GME and provide toolkits and resources to support PFCC in the learning environment. Participants advised against program or institutional requirements for PFCC, based on their perception that models are specialty and institution dependent, and “one size will not fit all.” One proposed approach called for the ACGME to develop a vision and some targeted, ideally validated, approaches, and let institutions and programs find their own way. A concrete suggestion was to include PFCC “milestones” in the Milestone Project. Finally, to ensure that the patient's voice is heard, participants suggested that ACGME consider direct patient input into its work by appointing patients or patient representatives to its board and committees.

Conclusions

The more than 70 participants in the design conference reflected a diversity of approaches to incorporate PFCC into the learning environment, as well as different stages of implementation. Across this diverse group of participants, an overarching consensus was that for PFCC to be sustainable, it has to be a fundamental expectation for resident learning and attainment of competence. Participants strongly concurred that improving the environment for patients has an enormous positive impact on the environment for learners.

Footnotes

Ingrid Philibert, PhD, MBA, is Senior Vice President of the Department of Field Activities, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME); Carl Patow, MD, is Executive Director of the HealthPartners Institute for Medical Education and Co-Chair of the ACGME's Advisory Group on Resident Education in Patient- and Family-Centered Care. At the time of the conference, Jim Cichon, MSW, was Associate Director of the Department of Field Activities, and lead staff for the Advisory Group; Mr. Cichon currently is the Associate Director of ACGME-International.

This article is dedicated to Patricia Sodomka, one of the pioneers of Patient- and Family-Centered Care in academic settings, who passed away in the spring of 2010 after a long and courageous battle with cancer. Without Pat's guidance and presence at the September 2009 conference, despite serious recurrent illness, and the expertise and guidance she provided to the round table, the conference and the larger ACGME initiative to explore PFCC would not have been possible.

Funding: The Design Conference and work of the PFCC Advisory Group were funded from ACGME operational funds. No external funding was received for this project.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine, Committee on Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Common Program Requirements, Effective July 2002. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/dutyHours/dh_dutyhoursCommonPR07012007.pdf, accessed April 11, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers & Systems (HCAPS). HCAPS Executive Insight. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Available at: http://www.hcahpsonline.org/executive_insight/default.aspx. Accessed April 11, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute for Family Centered Care. Patient- and family-centered care: a hospital self-assessment inventory. Available at: http://www.ipfcc.org/resources/other/hospital_self_assessment.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kondo Y. Kaoru Ishikawa: what he thought and achieved, a basis for further research. Qual Manag J. 1994;1(4):86–91. [Google Scholar]