Short abstract

A general practitioner and murderer

Few doctors have had as great an impact on British medicine as Harold Shipman. When he and his colleagues qualified from Leeds Medical School in 1970, none of them would ever have imagined that his obituary in the BMJ would have opened with such a sentence. But his impact, and his legacy, is incalculable. Few lives can have raised so many questions about how we practise and regulate medicine.

Britain's general practitioners are frequently the cornerstone of their community, offering care, compassion, and continuity. In return they are trusted—quite remarkably trusted. Shipman betrayed that trust in the most appalling and distressing way, killing at least 215, and possibly 260, of his patients.

Harold Frederick Shipman was born in Nottingham in 1946, the son of a lorry driver. No one in his family had ever been to university. While he was taking his A levels, his mother died from cancer at the age of 42. He met his wife, Primrose Oxtoby, at a bus stop while he was at Leeds University, and they married in 1966. They had four children.

Apart from the death of his mother, there was nothing unusual about his early years. At medical school, Fred—the name by which he was known throughout his later life—stood out only by being entirely unremarkable. So far, so normal.

Shipman became a general practitioner in Todmorden, West Yorkshire, in 1974. But something had clearly happened to him. By 1976 he was self administering pethidine obtained by fiddled prescriptions. He was taken to court, fined £600 by magistrates, referred to a psychiatric unit near York, and was issued with a warning by the General Medical Council but was not struck off.

By 1977 he had joined a group practice in Hyde but his violent mood swings made the partnership untenable and in 1992 he set up in singlehanded practice. No one knows when the killing first started, but from this point it escalated out of control. He killed people by injecting them with opiates, often at home, sometimes in the surgery. In 1998 another general practitioner in Hyde told the coroner of her suspicions, but after a police investigation it was felt that no further action was needed, and the killings continued.

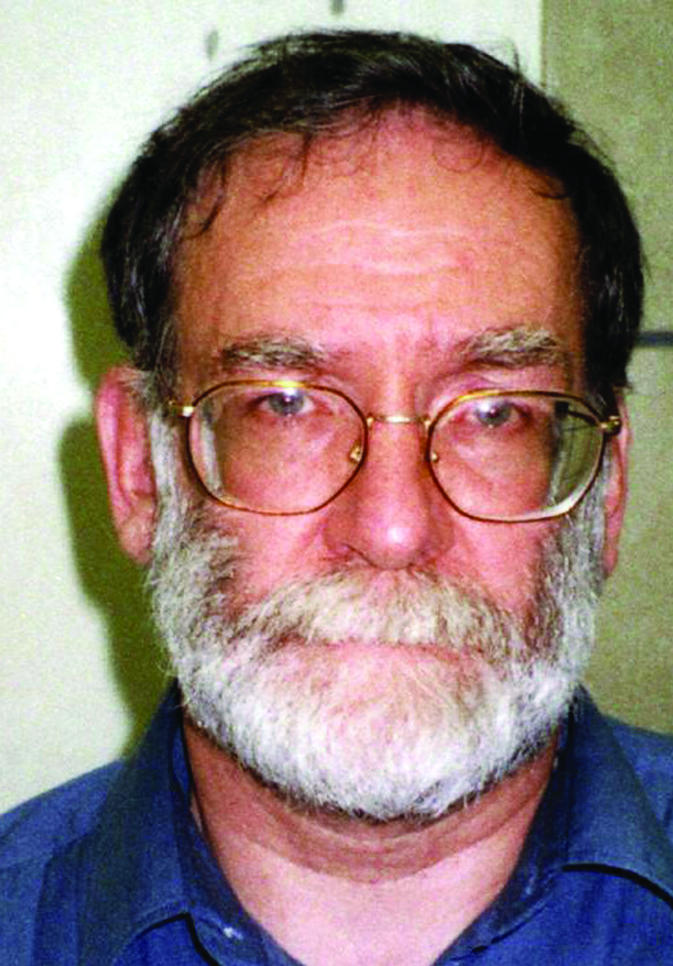

Figure 1.

Credit: REX

His final victim was Kathleen Grundy, an 81 year old former mayoress of Hyde. Extraordinarily he forged her will, using a battered old typewriter on which he wrote, “I give all my estate, money and house to my doctor. My family are not in need, and I want to reward him for all the care he has given me and the people of Hyde.” This was an absurdly clumsy forgery, with an obviously forged signature. It's hard not to believe that he wanted—at least unconsciously—to be caught. Or perhaps he thought that he was invincible.

Mrs Grundy's daughter was a solicitor and pursued the truth, which turned out to be shocking. Shipman was eventually charged with the murder of 15 women and found guilty on 31 January 2000. It was clear that he had covered his tracks by altering records and falsifying death certificates. On every level he had abused the trust that his patients put in him.

The report of the subsequent inquiry by Dame Janet Smith was published in 2001 and concluded that Shipman had unlawfully killed 215 patients, and that a real suspicion remained over 45 others. Shipman was sentenced to life—one of 20 prisoners in the United Kingdom who were told that they would never be released—and eventually, after giving no obvious cause for concern about his safety, he hanged himself in his cell with bedsheets tied to the bars of his window.

Most of the explanations for why Shipman killed his patients—leaving nearly 300 families bereaved and distraught—are probably too simple, too glib. Did he witness his mother's suffering, and believe that sudden death at the end of a trusted and friendly physician's syringe was a preferable option? Did he hate women (and most of his patients were women) for reasons that we cannot understand? Was he clinically insane? Was he terrifyingly sane? Was he obsessed with power—power that was perhaps exemplified by his choosing the time and manner of his own death, ultimately frustrating those who wanted to know “why?”

We will probably never know why he did what he did, but we can begin to see his legacy. At first thought his truly extraordinary actions might seem to have no implications for the ordinary business of general practice. But his murders have led to questions being asked about the function and strength of the GMC, the role of revalidation, how we deal with sick doctors, the purpose and reliability of death certification, the monitoring of cremation certification, the use of controlled drugs, the problem of isolated doctors, the value of clinical governance, the problems of whistleblowing, and the function of the coroners' service. The inquiry is working its way through these questions and is likely to have profound consequences for medicine. Even the GMC itself may be numbered among Shipman's victims.

He leaves Primrose and their four children, all of whom remained loyal to him.

Harold Frederick Shipman, former general practitioner Hyde, Greater Manchester (b 1946; q Leeds 1970), died in Wakefield prison on 13 January 2004.

We thank those who helped us greatly with this obituary.