Abstract

Autologous stem cells, recognized as the best cells for stem cell therapy, are associated with difficult extraction procedures that often lead to more traumas for the patients and time consuming laboratory work that delays their subsequent application. To combat such challenges, we have recently uncovered that shortly after biomaterial implantation, following the recruitment of inflammatory cells, substantial numbers of mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) and hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) were recruited to the implantation sites. These multipotent MSCs could be differentiated into various lineages in vitro. Inflammatory signals may be responsible for the gathering of stem cells, since there is a good relationship between biomaterial-mediated inflammatory responses and stem cell accumulation in vivo. In addition, the treatment with anti-inflammatory drug – dexamethasone – substantially reduced the recruitment of both MSC and HSC. The results from this work support that such strategies could be further developed towards localized recruitment and differentiation of progenitor cells. This may permit the future development of autologous stem cell therapies without the need for tedious cell isolation, culture and transplantation.

Keywords: Autologous stem cells, Hematopoietic stem cells, Mesenchymal stem cells, Foreign body response, Flow cytometry, Animal model, Osteogenic, Adipogenic, Neurogenic

1. INTRODUCTION

Stem cells have gained popularity in regenerative medicine not only due to their ability to self regenerate but also because they can differentiate into various types of specialized cells [1–5]. A major challenge for stem cell therapy is the source of cells. The use of embryonic stem cells is hindered by ethical concerns associated with cell isolation [6]. Although, the recent development of methods creating induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells provides a new opportunity in obtaining pluripotent stem cells [7–9], little is known about the long term safety of the iPS [7,10]. Therefore, a vast majority of human clinical trials rely on the use of adult stem cells [11–13].

Autologous adult stem cells are well established to be the best cells for stem cell therapy, although large number of autologous stem cells is hard to obtain. Adult stem cells can be extracted from bone marrow of the iliac crest [14], and liposuction lysates [15]. These methods require prolonged culture to get sufficient cell numbers and stem cells tend to differentiate in vitro making their expansion difficult [16]. Moreover, it has been shown that after a few passages bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells lose their ability to differentiate in vitro as well as in vivo [17,18]. Once injected into the body, stem cells often fail to function or even survive due to poor tissue integration and vascularization [19,20]. The difficulty associated with cell culture in vitro and cell function in vivo turns out to be major obstacles for the employment of adult stem cells in regenerative medicine [21]. Subcutaneous adipose tissue has also been shown to be an abundant source of adult stem cells, although such cells can be not obtained from all patients and the procedures involved to recover adipose stem cells, although less traumatic than bone marrow stem cell extraction, are still painful [22]. Such deficiencies impose major obstacles in the development and investigation of alternative stem cell therapeutic strategies.

The success of biomaterial implantation relies heavily on its ability to harmoniously integrate with the body. While a lot of impetus has been provided to implantable biomaterials using incorporation of stem cells and growth factors, most of the studies have been limited to complicated and cumbersome ex vivo cell extraction, expansion and scaffold seeding techniques followed by its implantation. Such strategies are time consuming and do not necessarily guarantee successful outcome.

It is known that biomaterial implantation is associated with the recruitment of a variety of cell types that includes mainly inflammatory cells. Several others and our group have very recently identified progenitor cells recruited by various biomaterial implants.[23,24] However, the types and sources of those progenitor and stem-like cells were not well defined in those studies. It was not known what triggers and influences the extent of stem-like cell recruitment. Our studies revealed that cells, bearing markers resembling mesenchymal stem cells (MSC, CD105+/Stro-1+/SSEA4+/CD45−/CD34−/CD56−) and hematopoietic stem cells (HSC, Sca-1+/ckit-/Lineage markers-) were found as early as 4 days in the wound fluid. In addition, such cells were also found around various subcutaneously implanted biomaterials. The extent of stem cell recruitment seemed to depend on the varying pro-inflammatory properties of different microspheres. Since various inflammatory cytokines were found to have been over expressed, we then hypothesized that suppressing the inflammatory response could alter the stem cell recruitment. Indeed there was evidence for inflammation playing a plausible role in autologous stem and progenitor cell recruitment. The results from this study provide a novel strategy for triggering autologous stem cell recruitment. Potentially, such cell recruitment can be augmented and differentiated into various lineages by delivery of suitable chemokines and cytokines. Further development of this technology may permit the future development of new autologous stem cell therapies without the requirement of cell isolation, culture and subsequent transplantation procedure.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Materials

Hydroxypropyl cellulose (HPC) powder (average Mw = 1 × 106) and N-isopropyl acrylamide (NIPAm) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI, USA). High-molecular weight poly (L-lactic acid) (PLLA, 137 kDa), was obtained from Birmingham Polymers (Birmingham, AL, USA). Polypropylene microspheres (35 microns) were bought from Polysciences, Inc (Warrington, PA). Primary antibodies (1:50) against CD73, CD90, CD105, Stro-1, CD45 and stage specific embryonic antigen-4 (SSEA-4) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Stem cell antigen-1 (Sca-1) and CD11b were purchased from BD Biosciences Pharmingen (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Antibody cocktail against lineage markers was procured from Miltenyl Biotec (Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Secondary antibodies (1:100) labeled with FITC or Texas Red were from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc. (West Grove, PA). Neurobasal medium, 1% N2 supplement, 1% eniciilin/Streptomycin (Gibco, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), trans-retinoic acid, β-tubulin and Oil Red O, Indomethacin, β-glycerolphosphate, 2-phospho-L-ascorbic acid, Dexamethasone (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), rh-brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) from Promega (Madison, WI) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) from Prospec-Tany Technogene Ltd (East Brunswick, NJ). All Balb/c mice used in this work were obtained from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY, USA).

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 Modified wound chamber

To mimic biomaterial-mediated cellular responses, PLLA tubes (inner diameter of 2 mm) were produced for this investigation. Briefly, solid Teflon rods (3 mm external diameter) were dip coated with PLLA (10 % w/v) in 1, 4-dioxane and frozen. Such tubes were then lyophilized for three days to extract the solvent, yielding PLLA tubes. Such tubes (length 1.5 cm) with an internal diameter of 3 mm and external diameter of 5 mm, were punched with holes using an 18 gauge needle and sterilized in 70% ethanol and exposed to UV light.

2.2.2 Microsphere synthesis

Various forms of biomaterials were used in this investigation. Specifically, N-isopropyl acrylamide (NIPAm) microspheres with an average size of 1 μm were synthesized using a free radical precipitation polymerization method as described earlier [25], and HPC microspheres with an average size of 6 μm were synthesized using modified precipitation polymerization techniques described earlier [26,27]. PLLA microspheres were synthesized according to a modified precipitation method with an average size of 15 μm [28]. It must be noted that our selection of different microspheres with different particles sizes was under the assumption that such microspheres could dictate varying extents of foreign body responses.

2.2.3 Animal Model

The animal use protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas at Arlington. For wound chamber studies, two PLLA tubes (1.5 cm long, 2 mm inner diameter) per animal, were implanted in the dorsal subcutaneous space of Balb/c mice. Three days post-implantation, wound fluid was aspirated using a 3 cc syringe with an 18 gauge needle. Cells were counted and aliquoted into two groups: for in vitro differentiation studies and for FACSArray analysis.

To determine the relationship between foreign body reactions and stem cell recruitment, microspheres made of HPC, NIPAm, PLLA and PP were used in the study. For that, 1.0 ml of microspheres (2 mg/ml) was implanted subcutaneously via 27 gauge needle in the Balb/C mice (male, 20 g body weight) [29,30]. After implantation for different periods of time (1, 2, 4, 7 and 14 days), the animals were sacrificed and implant and surrounding tissue were isolated for histological analyses.

The influence of implant-associated inflammatory responses on stem cell recruitment was assessed using anti-inflammatory agent, dexamethasone. Briefly, HPC microspheres were immersed in dexamethasone (1 mg/ml) or saline (as control) and then implanted subcutaneously in mice for 1 week. At the end of the studies, implant and surrounding tissue were recovered for histological analyses.

2.2.4 In vitro cell differentiation studies

Cells aspirated from the PLLA tubes were centrifuged and resuspended in DMEM with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotics (100 U penicillin and 100 μg streptomycin) at 37°C with 5% CO2. Non-adherent cells were removed and the attached cells provided with more media. Cells maintained in DMEM with 20% FBS and antibiotics served as control. When the cells reached almost 50% confluence, differentiation agents were added and cells analyzed as follows. To test the osteogenic potential, cells were incubated with DMEM + 10% FBS and 100 nM dexamethasone, 10 mM β-glycerolphosphate and 0.05 mM 2-phosphate-ascorbic acid. Cell differentiation into an osteogenic lineage was determined using Alizarin Red staining for calcified deposits [31]. To test the neuronal differentiation potential, neuronal differentiation condition consisted of Neurobasal medium supplemented with 0.5 μM all trans-retinoic acid, 1% fetal bovine serum, 5% horse serum, 1% N2 supplement and 1% antibiotics. N2 supplement is an optimized serum free supplement used in combination with neuronal differentiation media. In addition 10 ng/ml rh-BDNF was added for neuronal induction and cells were differentiated for 10 to 14 days followed by β-tubulin staining.[32,33] To test the adipogenic potential, cells were incubated with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin supplemented with 0.5 mM isobutylmethylxanthine, 100 nM IGF-1, 1 μM dexamethasone and 200 μM Indomethacin for 3 weeks. Media was fully changed every 3 days and cells evaluated after 3 weeks in culture. Oil Red O staining which stained lipid filled vacuoles in the adipogenic differentiated cells was performed [31]. Cells maintained in DMEM with 10% FBS and antibiotics served as control.

2.2.5 Flow Cytometric Analysis

The phenotypic determination of cell types was carried out using flow cytometric method. Briefly, cells were fixed in cold ethanol and resuspended in PBS containing 1% FBS. Cell aliquots (5 × 105 cells/200 μl) were incubated with mAbs against the following: (1) MSC: SSEA4+/CD45−; CD73+/CD105+/CD90+/CD45−; (2) HSC: Lin-/Sca-1+/ckit+; (3) Inflammatory cells: CD11b+. Flow cytometry was performed using a FACS Array and FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, CA, USA) and data was analyzed using BD CellQuest (BD Biosciences, CA, USA).

2.2.6 In vivo stem cell tracking

An in vivo stem cell tracking system was established to visualize the implant-mediated stem cell recruitment. Bone marrow MSCs was isolated from femurs and then cultured based on established procedures [34]. After 2nd passage, confluent MSCs were incubated with 5μM of near-infrared (NIR) fluorophore (X-sight) (Rochester, NY) at 37°C for 24 hours. Following wash with PBS twice, the X-sight labeled MSCs (2 × 106 cells/injection) were administered into mice bearing 1-day old PLLA scaffold implants via tail vein. After implantation for different periods of time, stem cell distribution was imaged by using Kodak In-vivo Multispectral Image System FX (configured for 760nm excitation, 830nm emission, 45s exposure, 8×8 binding, f-stop 2.5, 120mm field of view) to determine stem cells fluorescence intensity, and stem cell migration as published earlier [35].

2.2.7 Inflammatory cytokine profile in the implantation sites

Protein antibody microarray analysis was performed to compare the inflammatory cytokine profiles in tissue surrounding microspheres triggering different extent of tissue responses using mouse cytokine antibody array III (Raybiotech, Norcros, GA) following manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, 30 slices of tissue sections from HPC/tissue (strong inflammatory response) and NIPAm/tissue (weak inflammatory responses) and normal skin (control) were used to extract proteins produced by cells adjacent to the implants. It must be noted that the manufacturer recommends concentrated lysate that can be subsequently diluted at least 10 folds for array assay. Extraction of proteins was done using cell lysis buffer provided by manufacturer. For this, we dilute 2X Cell Lysis Buffer with H2O to obtain 1X Cell Lysis Buffer. Eluted proteins (50 microgram/sample) were spread on the mouse cytokine antibody array III which was treated with 100 μl of 1X Blocking Buffer in each well. Blocking buffer was decanted and sample was added and incubated at room temperature for 2 hours. Foaming was avoided during all the steps and the steps were performed under gentle rotation. Samples were decanted and the wells were washed 5 times with 1X Washing Buffer at room temperature with shaking. Biotin conjugated antibodies (70 μl) was added to each well and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature. Following this, the wells were washed as before and Alexa-Fluor 555 conjugated streptavidin was added and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature. The wells were washed as before and the image analysis of the slide was then carried out using Axon GenePix 4000B microarray scanner (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The ratio of relative expression was calculated after subtraction of the background intensity and comparison with the positive controls (biotin-conjugated protein available on the slides). The fluorescence ratio for each spot was further processed using macros in EXCEL to identify cytokines/growth factor with a ratio of 2.0 or above (up-regulated cytokines) or a ratio of 1.0 or below (down-regulated cytokines) with respect to the control values.

2.2.8 Histological evaluation of inflammatory/stem cell recruitment

All histological evaluations were carried out using frozen section technique. All implants and surrounding tissues were frozen in OCT compound (Polysciences Inc., Warrington, PA) and then sectioned into 6 μm tissue using a Leica Cryostat (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). To assess the tissue responses to microsphere implants, some of these slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) as described earlier [29,30]. For assessing the extent of inflammatory cell, stem cells, immunofluorescence analyses were carried out on some slides following established procedures [29,30]. Specifically, immunofluorescence analyses were used to quantify the density of implant associated inflammatory cells (CD11b+); hematopoietic stem cells (Lin-/Sca-1+/ckit+), and mesenchymal stem cells (CD105+/Stro-1+/SSEA4+/CD45−/CD34−/CD56−). DAPI staining was done to locate the cell nuclei. Stained sections were imaged using a Leica fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, GmbH) equipped with a CCD Camera (Retiga EXi, QImage). All images were analyzed using NIH ImageJ to assess the extent of implant-mediated cellular responses using established procedures [29,30,36].

2.2.9 Statistical Analyses

Data was expressed as mean ± SD and groups were compared using Student t- test. Differences were considered statistically significant when p ≤ 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Progenitor cells were found in the wound fluid

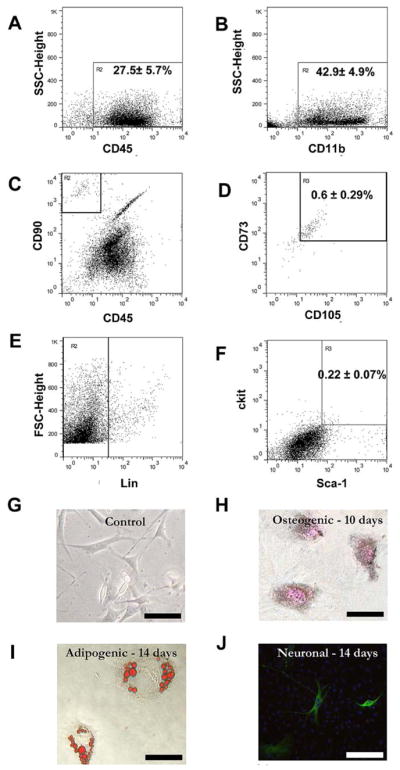

It is well established that foreign body reactions are accompanied with the accumulation of inflammatory cells. To determine the cell types in the biomaterial implantation site, ascites were collected from 3–5 day PLLA tube implants and then analyzed using flow cytometry method. As expected, we found that the wound fluid contains many CD45+ (27.5 ± 5.7 %) and CD11b+ (42.9 ± 4.9 %) and inflammatory cells (Figure 1A and B respectively). Rather surprisingly, our analyses also revealed that small numbers of MSC (CD73+/CD105+/CD90+/CD45−) (0.60 ± 0.29 %) (Figure 1C–D) and HSC (Lin-/Sca-1+/c-kit+) (0.22 ± 0.07 %) (Figure 1E–F), were present in the wound fluid. It should be noted that the Lineage negative cells were gated (Figure 1E) so as to determine the approximate numbers of HSCs in the pool of wound fluid cells and the wound fluid was not enriched for non-hematopoietic cells. To assess their multipotency, the wound fluid stem cells were cultured in the presence of various differentiation cocktails. While the control cells showed an undifferentiated morphology (Figure 1G), after 10 days in osteogenic differentiation medium, Alizarin Red staining showed the presence of calcified deposits indicative of osteogenic activity (Figure 1H). Both adipogenic and chondrogenic differentiation medium treated cells showed adipogenic activity (Figure 1I) based on Oil Red O staining, and neuronal differentiation based on β-tubulin staining (Figure 1J) by day 14. This indicates that wound fluid stem cells could differentiate into mesenchymal lineages in vitro.

Figure 1. Characterization of cells in wound fluid aspirates using flow cytometry analyses.

In wound fluid aspirates, the majority of cells were inflammatory in nature based on (A) CD45+ and (B) CD11b+ marker expression. The wound fluid also contained some number of (C–D) mesenchymal stem cells (CD73+/CD105+/CD90+/CD45−) along with (E–F) hematopoietic stem cells (Lin-/Sca1+/c-kit+). Plastic adherent cells from such aspirates were treated with various specific differentiation medium. (G) Control untreated cells remained largely undifferentiated. At various time points post-treatment cells were stained with (H) von Kossa for osteogenic (day 10); (I) Oil Red O for adipogenic (day 14) (J) and β-tubulin for neuronal differentiation (day 14). Magnification: 200X; Scale bar = 20 μm.

3.2 Different types of biomaterials triggered various extent of stem cell recruitment

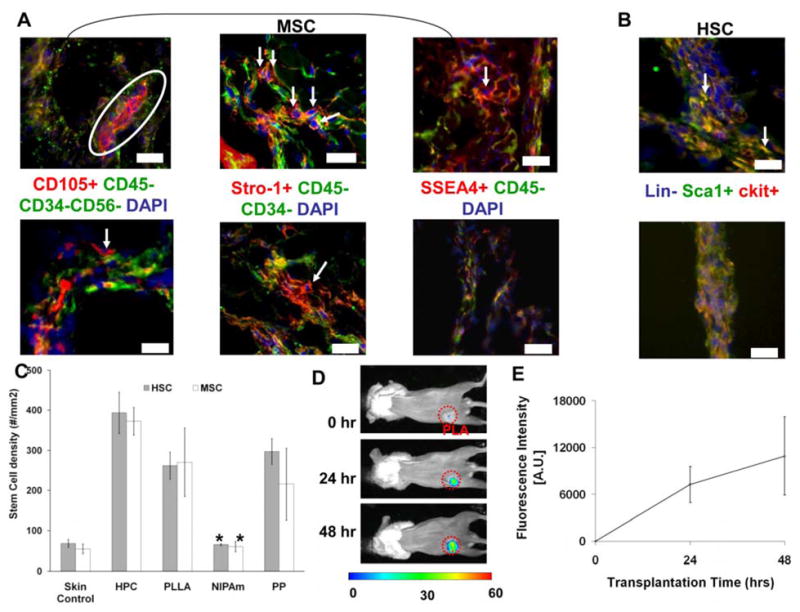

Although stem cells were found in the wound fluid from the wound chamber, it was not clear whether some of these stem cells resided in or surrounding biomaterial implants. Furthermore, it has not been determined whether biomaterials triggering different tissue responses would prompt varying extent of stem cell recruitment. To find the answer, microspheres (to provide high surface area for cells to interact with minimal surgical trauma) made of PLLA (used for tissue engineering scaffolds), NIPAm (used for drug delivery applications),[37] PP and HPC (both used for drug delivery) were implanted for 7 days (sufficient time for both inflammatory cells and stem cell responses) and then histologically analyzed. Specifically, microspheres made of HPC, PLLA and PP prompted significant recruitment of MSC (with different sets of markers, including CD105+/CD45−/CD34−/CD56−, Stro-1+/CD45−/CD34−, and SSEA4+/CD45−) and HSCs (Lin-/Sca-1+/ckit+) while NIPAm microsphere implants were found to be associated with four times lesser number of stem and progenitor cells (Figure 2A, B and C). The effect of biomaterial implants on stem cell recruitment was supported by an imaging study in which X-sight-labeled MSCs were intravenously transplanted into animals bearing 1-day old microsphere implants. Indeed, we found that, shortly after implantation, large numbers of MSCs were found to accumulate in the area with microsphere implants (Figure 2D) and the numbers of recruited MSCs increased with time (Figure 2E). Since the microspheres were implanted via syringe injection with minimal or no trauma, it is likely that the accumulation of MSC is mediated by an active recruitment.

Figure 2. Cells accumulate in the tissue around different microsphere implants (HPC, PLLA, NIPAm, and PP).

Based on the expression of various markers cells were quantified over a period of 7 days. (A) Histological staining of MSCs (with varying sets of markers including CD105+/CD45−/CD34−/CD56−, Stro1+/CD45−/CD34− and SSEA4+/CD45−) surrounding proinflammatory material PP (top panel) vs. NIPAm (lower panel). All positive markers were tagged with red while negative markers were labeled with red. Arrows indicate the MSCs uniquely expressing red color (signifying positive marker expression). All cells were counterstained with DAPI nucleus stain to aid in cell quantification(B) Histological staining of HSCs (Lin-/Sca1+/c-kit+) adjacent to PP materials (top panel) and NIPAm materials (lower panel). Arrows indicate the HSC expressing Sca-1 and c-kit and lacking expression of lineage markers. Images mag 200X. Scale bar = 50 μm. (C) Quantification of density of MSCs and HSCs surrounding different implants and in untreated normal skin. Estimated densities of MSCs and HSCs surrounding different implants are skin control (MSC= 54.58±12.01, HSC=68.25±9.85 cells/mm2); HPC (MSC=372.5±34.1, HSC=393.4±51.7 cells/mm2); PLLA (MSC= 270.1±85.2, HSC= 262±33.9 cells/mm2); NIPAm (MSC= 60.2±13, HSC=65.4±2.3 cells/mm2); PP (MSC= 215.6±89.7, HSC=297.3±32.2 cells/mm2). Data are mean ± SD. Significance of PLLA, NIPAm, PP vs. HPC; * p< 0.05. (D). Images of recruited X-sight labeled MSC to the subcutaneous area with 1-day PLLA microsphere implants. (E) Trend of MSC recruitment to the subcutaneous microsphere implantation sites based on the localized fluorescence intensities.

3.3 Acute inflammatory cells precede stem cell homing

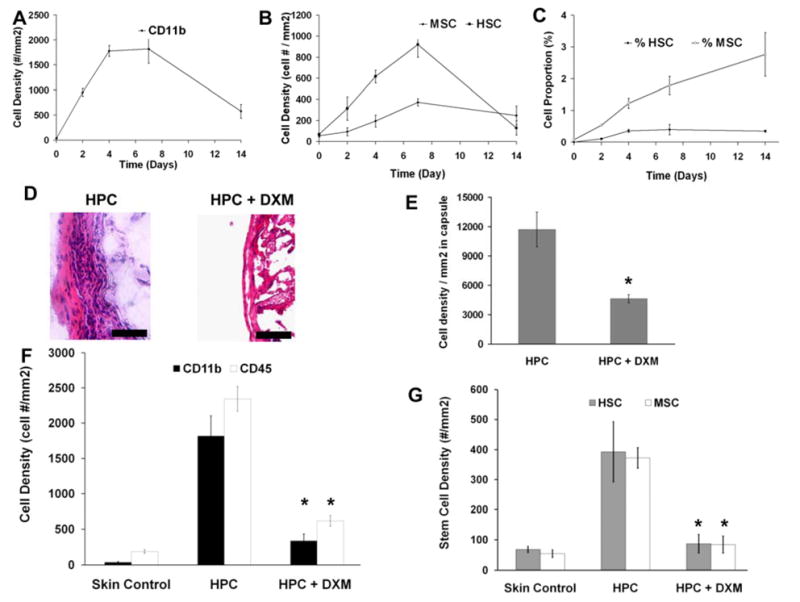

The interesting relationship between inflammatory cells and stem cells warranted the study of kinetic responses between these two types of cells. For that, we quantified the presence of various cell types around the subcutaneous HPC microsphere (which prompt intermediate cellular responses) implanted over a period of time (0, 2, 4, 7, and 14 days) (Figure 3A–C). As anticipated and in agreement with earlier findings in biomaterial-mediated inflammatory responses, the percentages of CD11b+ inflammatory cells (Figure 3A) around the implant tissue increased until around day 4 (~ 35%) after which the percentage declined sharply to ~10% on day 14. Differing from inflammatory cell responses, stem cell numbers peaked by day 7 (Figure 3B). We found that the proportion of MSCs surrounding biomaterial implants continued increasing with time (at least until 14 days) while the percentage of HSCs reached plateau around 4 days and stayed at the same level during the rest of this study (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Effect of microsphere implant and anti-inflammatory agent treatment on cell recruitment kinetics.

Quantitative analysis of (A) CD11b+ inflammatory cell number which increased until around day 4 (~ 35%) after which the percentage declined sharply to ~10% on day 14, (B) MSCs (Stro1+/CD45−/CD34−) and HSCs (Lin-/Sca1+/c-kit+) and (C) proportion of MSCs and HSCs recruited to the implantation sites. For 7-day HPC implants, some of the animals were treated with HPC soaked with anti-inflammatory drug, dexamethasone (DXM). (D) Representative histological images of fibrotic capsular region in untreated control vs. DXM treated mice. (Mag 400 X). (E) Overall cell density in fibrotic capsular region in untreated control vs. DXM treated mice. (F) The localized release of DXM on the recruitment of CD11b+ inflammatory cells and CD45+ immune cells in HPC implant-bearing mice. (G) Numbers of stem cells (both HSC and MSC) in the implant tissue and untreated normal skin control. Images mag 200X. Scale bar = 50 μm Data are mean ± SD. Significance of (HPC+DXM) vs. HPC; * p< 0.05.

3.4 Suppressing the inflammatory stimulus hinders stem cell recruitment

Our results so far support the idea that inflammatory responses influence stem cell recruitment. To test the potential role of inflammatory products on stem cell recruitment, we studied the effect of blocking the inflammatory process on stem cell recruitment. HPC microspheres were soaked in an anti-inflammatory drug, dexamethasone (DXM) (1 mg/ml) prior to subcutaneous implantation. At day 7 (when the cell numbers remained high based on earlier observations), we found that the administration of DXM substantially reduced the inflammatory response based on fibrous capsule thickness around the implant (Figure 3D). There was an almost 60% decrease in cell density around the DXM coated implant (Figure 3E). Specifically, there was a reduction in the numbers of inflammatory cells based on expression of CD11b and CD45 markers after administration of DXM (Figure 3F). Having seen that both overall capsular cell density and inflammatory cell density in the capsule went down after DXM administration, in support of our hypothesis, we observed ~70% reduction in the numbers of recruited stem cells (both HSC and MSC) compared to untreated controls (Figure 3G).

3.5 Localized production of inflammatory cytokines may dictate stem cell responses

Although many inflammatory cytokines/chemokines have been linked to stem cell migration, the molecular mechanism(s) and signals required for implant-mediated stem cell homing is mostly undetermined. To identify the potential inflammatory cytokines mediating stem cell buildup, we compared the inflammatory cytokine profiles in tissue surrounding HPC implants (with most inflammatory cells and stem cells) vs. untreated normal skin controls and HPC implants vs. NIPAm implants (with the least cells) (Table 1). HPC was selected instead of PP or PLLA for comparison with NIPAm, since the injection of HPC is associated with minimal trauma unlike PP or PLLA which has to be implanted surgically. Interestingly, our results have shown that a very high upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines like Macrophage Inflammatory Protein-1α (MIP-1α)/CCL3 (13–20X) and CXCL2/MIP-2 (14–23X) was seen in HPC implants as compared with untreated normal skin and NIPAm implants. In addition, a high expression of several pro-inflammatory cytokines like Monocyte Chemotactic Protein (MCP-1)/CCL2 (7–20X), MIP-1γ/CCF18 (3–8X), and MIP-2/CXCL2 (14–23X) is seen in the HPC implant group as compared with NIPAm. Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) which is a pro-fibrotic cytokine has a ~41X increase in expression in the HPC implant group as compared to normal skin which did not receive any implants and an 11X increase compared to the least inflammatory NIPAm group. It must be noted that a few pro-inflammatory cytokines like Tumor Necrosis Factor–α (TNF-α), RANTES/CCL5, Granulocyte Colony Stimulating Factor (G-CSF) and Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) were not significantly up-regulated. Similar protein microarray assays were carried out three times using different samples. Only the expression levels among different tests with similar trends (upregulation/down regulation) were listed on the table. Our results show >90% agreements among all tests.

Table 1.

Inflammatory cytokine expression in the tissues surrounding HPC microsphere implant group (associated with strong stem cell homing) compared with untreated normal skin control and tissue surrounding NIPAm microspheres (associated with weak stem cell response) after 7 days

| Expression | ||

|---|---|---|

| Protein | HPC vs. Normal Skin Control | HPC vs. NIPAm |

| CXCL1/KC | 3.62 | 3.24 |

| CCL2/MCP-1 | 11.47 | 6.63 |

| CCL3/MIP-1α | 19.75 | 13.42 |

| CCF18/MIP-1γ | 7.52 | 2.62 |

| CXCL2/MIP-2 | 23.49 | 14.35 |

| CCL4/PF-4 | 4.17 | Not significant |

| TIMP-1 | 41.26 | 11.42 |

| CCLS/RANTES; CXCL5/LIX; Fas Ligand; GM-CSF; G- CSF, IGFBP-3,5,6; IL- 2,3,4,5,6,9; IFN-γ, TNF-α; TPO; VCAM- 1; VEGF; SCF; SDF- 1, | Not significant | Not significant |

4. DISCUSSION

Despite the tremendous potential shown by stem cells in treatment of diseases and regenerative tissue engineering [38–40], it has quite a few drawbacks. Firstly, there is a lack of safe and reliable sources for large numbers of stem cells. Secondly, transplanted allogenic stem cells often exert immune reactions [41,42], which may eventually lead to their death [42,43]. Wound healing responses promote the recruitment of MSCs/HSCs [44,45], and both groups of cells have been shown to participate in tissue regeneration [46–48]. It thus, would be highly desirable if biomaterial implants were to be developed to direct autologous stem cell responses to resemble those in wound healing reactions. This can have profound implications from a regenerative medicine standpoint and this has been the driving force behind this work. This study supports that implantation of a biomaterial can trigger localized inflammatory responses and indirectly recruit multipotent autologous stem cells to the implantation site. Their subsequent behavior could then be controlled so as to yield a desired outcome.

Our first objective was to characterize the cells arriving at the site of a biomaterial implant and demonstrate that they are multipotent. For this we used a wound chamber model, wherein PLLA was used to fabricate the wound chambers as it is a commonly used FDA approved biomaterial for fabricating tissue engineering scaffolds. The implantation of PLLA tubes was found to prompt the influx of cells (mainly inflammatory CD11b+ cells, and other peripheral blood cells) into the chamber lumen within 24–48 hours as determined by flow cytometry. Although most of CD11b+ inflammatory cells are derived from CD45+ phagocytes, we repeatedly found more CD11b+ cells than CD45+ cells near the implant sites. Such discrepancies might be caused by the changes in the expression of cell surface markers due to the cellular phenotypic changes. For example, it has been found that withdrawal of IL-6 led to loss of expression of CD45 in some cells.[49] Also, monocytes and macrophages have been shown to change phenotype into myofibroblast like cells upon contact with implant surface.[50] In addition to inflammatory cells, abundant multipotent MSCs (CD73+/CD105+/CD90+/CD45−),[12,51,52]and HSCs (Sca-1+/c-kit+/Lineage markers-)[53–55] were recruited to the implant sites. This observation is supported by a previous study that employed wound chambers [56]. We are aware that the cell surface markers are not sufficient to determine the function of recruited stem cells. As a true test of their “plasticity”, it is desirable to show that these cells can, not just express these progenitor cell markers, but also adhere to plastic and differentiate into various lineages under the appropriate conditions [57,58]. We were able to use various specific differentiation cocktails and induce lineage specific differentiation of the cells into osteogenic, adipogenic and neuronal lineages. Our qualitative results agree with stem cell differentiation studies in which wound chamber-derived MSCs were differentiated into various lineages [31]. This further supports previous observations that the collections of cells that are recruited in response to a wound or injury include stem cells. On the other hand, future study is needed to determine the functionality of HSCs.

Despite the availability of such information there has not been any documented evidence of autologous stem cells around an implant in the tissue space. Since our studies along with others have suggested that inflammatory chemokines could play a role in the autologous stem cell recruitment phenomenon, we used various types of microsphere implants to test whether they could trigger different extents of MSCs recruitment. The selection of materials was based on various factors; PLLA is commonly used for fabricating tissue engineering scaffolds; NIPAm hydrogel is associated with low inflammatory response [37], and along with PP can be used for drug delivery applications. HPC nanogel has been made for controlled drug release [59]. The paucity of data on the presence of stem cells in the tissue space around an implanted biomaterial could be due to the fact that the selection of markers for MSCs, especially in tissue space is highly debatable. As such based on an extensive search of available literature [51,52,57,58,60], a set of markers was short-listed. It must be noted that MSCs are positive for CD105, Stro-1 and very recently it was found that cells expressing SSEA4+ and CD45− cells are multipotent MSCs [3,15,61]. In fact there have been studies of late that have shown that SSEA-4 is a marker for primitive MSCs in both murine and human bone marrow [3,62]. Cells positive for CD105, Stro-1, SSEA4 and the generally accepted negative markers CD45, CD34 and CD56 were identified as multipotent MSCs [51,57,58,60]. Based on the expression of markers Sca-1 and c-kit and negative expression for Lineage markers HSCs were identified as in earlier publications [53–55]. It must be noted that very few stem cells were found in the “untreated” subcutaneous soft tissue or the animals which did not receive an implant. The expression of Stro-1, which is a characteristic surface antigen, found on bone marrow derived MSC was quantified to indicate the source of MSCs, which in this study was predominantly from the bone marrow. Although we have not carried out a detailed investigation of the various sources of these multipotent stem cells, we do see indications of bone marrow derived stem cells (BMSC) being present based on the expression of specific BMSC markers. However, the presence of “tissue stem cells” and other sources cannot be ruled out.

This study has demonstrated that microsphere implants with varying degree of pro-inflammatory properties also trigger different extent of MSCs recruitment. By analyzing tissue responses to materials prompting varying degrees of inflammatory responses, we found that there was a good relationship between stem cell and inflammatory cell recruitment. It is well established that material surface properties affect the extent of inflammatory responses [29,30]. However, it must be noted that the microspheres used had sizes varying between 1 and 15 μm and the variation is sizes can also be attributed to different materials and methods used to synthesize them.

Interestingly, we found that the administration of anti-inflammatory drug – dexamethasone – curtailed not only inflammatory cell responses but also stem cell homing. The recruitment of stem cells is likely to be triggered by inflammatory products, since inflammatory cell numbers achieved their maxima 3 days before stem cells. This observation also agrees well with previous studies which have found that inflammatory responses play a role in stem cell homing [39,63,64]. The results from this work also support the idea that the localized biomaterial-mediated inflammatory responses could be used as a controlled means to elicit autologous stem cell recruitment. Our findings agree well with previous studies which showed reduced MSC and neural stem cell proliferation following anti-inflammatory drug administration [65,66]. Interestingly, since dexamethasone is widely used to dampen the foreign body response, it is worthwhile to speculate whether its administration would provide the desired outcome if stem cell recruitment is diminished. It must be also noted that a previously published study has found that pretreatment of MSCs with dexamethasone for various periods has an effect on its subsequent in vivo differentiation into an osteogenic lineage.[67] Based on this and our data, we can speculate that for preseeded scaffolds conditioning with dexamethasone might be advantageous, however for in vivo recruitment and differentiation of stem cells at implants, administering dexamethasone locally might not be the right strategy. On the other hand, it has been shown that the regeneration of tissues can occur without the recruitment of stem cells. [50,68] The potential role of recruited stem cells on tissue regeneration near the implant sites is yet to be evaluated.

So as to understand the mechanism behind the recruitment of autologous stem cells in response to inflammatory stimuli, we analyzed the expression of various cytokines around the pro-inflammatory HPC implant group and compared it with the least inflammatory NIPAm group and the possible role they could have played in recruiting stem cells. The increase in production of several inflammatory cytokines, including CCL2/MCP-1, CCL3/MIP-1α, CCF18/MIP-1γ and TIMP-1 supports the pro-inflammatory nature of HPC microsphere implants. Although, it is well established that CC chemokines like CCL2/MCP-1 and CCL3/MIP-1α prompt the migration of monocyte/macrophages,[69–71] The production of CCL5/RANTES another prominent proinflammatory cytokine, as also TNF-α, G-CSF and IFN-γ was not significant. Although the exact mechanism governing this is not clear, it is possible that certain conditions in the milieu around the implant could play a role in down-regulation of these cytokines. In light of this finding, it must be noted that in recent studies, many of these chemokines have been found to participate in the recruitment of stem cells. For example, CCL3/MIP-1α is found to mobilize hematopoietic progenitors [72,73]. CCL2/MCP-1 has been shown to be a potent chemoattractant for bone marrow stem cells, especially MSC [74]. In addition, increased production of CCL4/Platelet Factor 4 (PF4) may contribute to the enhanced stem cell recruitment via the adhesion of HSC to endothelial cells [75,76]. Interestingly, we also observed a slightly decreased expression of IFN-γ. The reduction of IFN-γ may be correlated with MSC recruitment, since an earlier study showed that in the presence of MSCs, IFN-γ production is reduced [77].

Overall, our findings indicate that the release of inflammatory chemokines and growth factors play an important role in autologous stem cell recruitment. This can be harnessed to play a vital role in tissue regeneration strategies. In such scenarios, biomaterial implant can be made in different forms (spheres, gel or scaffold) to release a variety of agents able to differentiate stem cells into different lineages. By implanting such materials in or nearby diseased or injured tissue, autologous stem cells can be recruited to a site and then turned into specialized cells for in situ tissue regeneration without the cell recovery and handling problems associated with current stem cell therapies and tissue engineering applications.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant EB007271. The authors would also like to thank Paul Thevenot for help with in vitro differentiation study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bruder SP, Kurth AA, Shea M, Hayes WC, Jaiswal N, Kadiyala S. Bone regeneration by implantation of purified, culture-expanded human mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res. 1998;16:155–62. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100160202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loebinger MR, Aguilar S, Janes SM. Therapeutic potential of stem cells in lung disease: progress and pitfalls. Clin Sci (Lond) 2008;114:99–108. doi: 10.1042/CS20070073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gang EJ, Bosnakovski D, Figueiredo CA, Visser JW, Perlingeiro RC. SSEA-4 identifies mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow. Blood. 2007;109:1743–51. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-010504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li TS, Hayashi M, Ito H, Furutani A, Murata T, Matsuzaki M, Hamano K. Regeneration of infarcted myocardium by intramyocardial implantation of ex vivo transforming growth factor-beta-preprogrammed bone marrow stem cells. Circulation. 2005;111:2438–45. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000167553.49133.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Price MJ, Chou CC, Frantzen M, Miyamoto T, Kar S, Lee S, Shah PK, Martin BJ, Lill M, Forrester JS, et al. Intravenous mesenchymal stem cell therapy early after reperfused acute myocardial infarction improves left ventricular function and alters electrophysiologic properties. Int J Cardiol. 2006;111:231–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lei T, Jacob S, Ajil-Zaraa I, Dubuisson JB, Irion O, Jaconi M, Feki A. Xeno-free derivation and culture of human embryonic stem cells: current status, problems and challenges. Cell Res. 2007;17:682–8. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amabile G, Meissner A. Induced pluripotent stem cells: current progress and potential for regenerative medicine. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi KD, Yu J, Smuga-Otto K, Salvagiotto G, Rehrauer W, Vodyanik M, Thomson J, Slukvin I. Hematopoietic and endothelial differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:559–67. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishikawa S, Goldstein RA, Nierras CR. The promise of human induced pluripotent stem cells for research and therapy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:725–9. doi: 10.1038/nrm2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colman A, Dreesen O. Induced pluripotent stem cells and the stability of the differentiated state. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:714–21. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prentice DA, Tarne G. Treating diseases with adult stem cells. Science. 2007;315:328. doi: 10.1126/science.315.5810.328b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prockop DJ, Olson SD. Clinical trials with adult stem/progenitor cells for tissue repair: let’s not overlook some essential precautions. Blood. 2007;109:3147–51. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-013433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Togel F, Westenfelder C. Adult bone marrow-derived stem cells for organ regeneration and repair. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:3321–31. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazzini L, Mareschi K, Ferrero I, Vassallo E, Oliveri G, Boccaletti R, Testa L, Livigni S, Fagioli F. Autologous mesenchymal stem cells: clinical applications in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurol Res. 2006;28:523–6. doi: 10.1179/016164106X116791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell JB, McIntosh K, Zvonic S, Garrett S, Floyd ZE, Kloster A, Di Halvorsen Y, Storms RW, Goh B, Kilroy G, et al. Immunophenotype of human adipose-derived cells: temporal changes in stromal-associated and stem cell-associated markers. Stem Cells. 2006;24:376–85. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stocum DL, Zupanc GK. Stretching the limits: stem cells in regeneration science. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:3648–71. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonab MM, Alimoghaddam K, Talebian F, Ghaffari SH, Ghavamzadeh A, Nikbin B. Aging of mesenchymal stem cell in vitro. BMC Cell Biol. 2006;7:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-7-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crisostomo PR, Wang M, Wairiuko GM, Morrell ED, Terrell AM, Seshadri P, Nam UH, Meldrum DR. High passage number of stem cells adversely affects stem cell activation and myocardial protection. Shock. 2006;26:575–80. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000235087.45798.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ikada Y. Challenges in tissue engineering. Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 2006;3:589–601. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2006.0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laschke MW, Harder Y, Amon M, Martin I, Farhadi J, Ring A, Torio-Padron N, Schramm R, Rucker M, Junker D, et al. Angiogenesis in tissue engineering: Breathing life into constructed tissue substitutes. Tissue Engineering. 2006;12:2093–2104. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romanov YA, Svintsitskaya VA, Smirnov VN. Searching for alternative sources of postnatal human mesenchymal stem cells: candidate MSC-like cells from umbilical cord. Stem Cells. 2003;21:105–10. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-1-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jang S, Cho HH, Cho YB, Park JS, Jeong HS. Functional neural differentiation of human adipose tissue-derived stem cells using bFGF and forskolin. BMC Cell Biol. 2010;11:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-11-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee SJ, Van Dyke M, Atala A, Yoo JJ. Host cell mobilization for in situ tissue regeneration. Rejuvenation Res. 2008;11:747–56. doi: 10.1089/rej.2008.0691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koshy A, Weng H, Tang L. Biomaterial implantation prompts the recruitment of stem cells in mice. Memphis: 2005. p. 599. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen KT, Shukla KP, Moctezuma M, Braden AR, Zhou J, Hu Z, Tang L. Studies of the cellular uptake of hydrogel nanospheres and microspheres by phagocytes, vascular endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;88:1022–30. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao J, Haidar G, Lu XH, Hu ZB. Self-association of Hydroxypropyl Cellulose in water. Macromolecules. 2001;34:2242–2247. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu XH, Hu ZB, Gao J. Synthesis and light scattering study of hydroxypropyl cellulose microgels. Macromolecules. 2000;33:8698–8702. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen JL, Chiang CH, Yeh MK. The mechanism of PLA microparticle formation by water-in-oil-in-water solvent evaporation method. J Microencapsul. 2002;19:333–46. doi: 10.1080/02652040110105373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamath S, Bhattacharyya D, Padukudru C, Timmons RB, Tang L. Surface chemistry influences implant-mediated host tissue responses. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;86:617–26. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nair A, Zou L, Bhattacharyya D, Timmons RB, Tang L. Species and density of implant surface chemistry affect the extent of foreign body reactions. Langmuir. 2008;24:2015–24. doi: 10.1021/la7025973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kretlow JD, Jin YQ, Liu W, Zhang WJ, Hong TH, Zhou G, Baggett LS, Mikos AG, Cao Y. Donor age and cell passage affects differentiation potential of murine bone marrow-derived stem cells. BMC Cell Biol. 2008;9:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-9-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hermann A, Gastl R, Liebau S, Popa MO, Fiedler J, Boehm BO, Maisel M, Lerche H, Schwarz J, Brenner R, et al. Efficient generation of neural stem cell-like cells from adult human bone marrow stromal cells. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:4411–22. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hermann A, Liebau S, Gastl R, Fickert S, Habisch HJ, Fiedler J, Schwarz J, Brenner R, Storch A. Comparative analysis of neuroectodermal differentiation capacity of human bone marrow stromal cells using various conversion protocols. J Neurosci Res. 2006;83:1502–14. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fiorina P, Jurewicz M, Augello A, Vergani A, Dada S, La Rosa S, Selig M, Godwin J, Law K, Placidi C, et al. Immunomodulatory function of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in experimental autoimmune type 1 diabetes. J Immunol. 2009;183:993–1004. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thevenot PT, Nair AM, Shen J, Lotfi P, Ko CY, Tang L. The effect of incorporation of SDF-1alpha into PLGA scaffolds on stem cell recruitment and the inflammatory response. Biomaterials. 2010;31:3997–4008. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abramoff MD, Magelhaes PJ, Ram SJ. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics International. 2004;11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weng H, Zhou J, Tang L, Hu Z. Tissue responses to thermally-responsive hydrogel nanoparticles. J Biomater Sci Polymer Edn. 2004;15:1167–1180. doi: 10.1163/1568562041753106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang CH, Cherng WJ, Verma S. Drawbacks to stem cell therapy in cardiovascular diseases. Future Cardiol. 2008;4:399–408. doi: 10.2217/14796678.4.4.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Imitola J, Raddassi K, Park KI, Mueller FJ, Nieto M, Teng YD, Frenkel D, Li J, Sidman RL, Walsh CA, et al. Directed migration of neural stem cells to sites of CNS injury by the stromal cell-derived factor 1alpha/CXC chemokine receptor 4 pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:18117–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408258102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mourkioti F, Rosenthal N. IGF-1, inflammation and stem cells: interactions during muscle regeneration. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:535–42. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nauta AJ, Westerhuis G, Kruisselbrink AB, Lurvink EG, Willemze R, Fibbe WE. Donor-derived mesenchymal stem cells are immunogenic in an allogeneic host and stimulate donor graft rejection in a nonmyeloablative setting. Blood. 2006;108:2114–20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-011650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swijnenburg RJ, Schrepfer S, Govaert JA, Cao F, Ransohoff K, Sheikh AY, Haddad M, Connolly AJ, Davis MM, Robbins RC, et al. Immunosuppressive therapy mitigates immunological rejection of human embryonic stem cell xenografts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:12991–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805802105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grinnemo KH, Kumagai-Braesch M, Mansson-Broberg A, Skottman H, Hao X, Siddiqui A, Andersson A, Stromberg AM, Lahesmaa R, Hovatta O, et al. Human embryonic stem cells are immunogenic in allogeneic and xenogeneic settings. Reprod Biomed Online. 2006;13:712–24. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fathke C, Wilson L, Hutter J, Kapoor V, Smith A, Hocking A, Isik F. Contribution of bone marrow-derived cells to skin: collagen deposition and wound repair. Stem Cells. 2004;22:812–22. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-5-812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu Y, Wang J, Scott PG, Tredget EE. Bone marrow-derived stem cells in wound healing: a review. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15 (Suppl 1):S18–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cho KA, Ju SY, Cho SJ, Jung YJ, Woo SY, Seoh JY, Han HS, Ryu KH. Mesenchymal stem cells showed the highest potential for the regeneration of injured liver tissue compared with other subpopulations of the bone marrow. Cell Biol Int. 2009;33:772–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kode JA, Mukherjee S, Joglekar MV, Hardikar AA. Mesenchymal stem cells: immunobiology and role in immunomodulation and tissue regeneration. Cytotherapy. 2009;11:377–91. doi: 10.1080/14653240903080367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moioli EK, Clark PA, Chen M, Dennis JE, Erickson HP, Gerson SL, Mao JJ. Synergistic actions of hematopoietic and mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells in vascularizing bioengineered tissues. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3922. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mahmoud MS, Ishikawa H, Fujii R, Kawano MM. Induction of CD45 expression and proliferation in U-266 myeloma cell line by interleukin-6. Blood. 1998;92:3887–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stewart HJ, Guildford AL, Lawrence-Watt DJ, Santin M. Substrate-induced phenotypical change of monocytes/macrophages into myofibroblast-like cells: a new insight into the mechanism of in-stent restenosis. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;90:465–71. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chamberlain G, Fox J, Ashton B, Middleton J. Concise review: mesenchymal stem cells: their phenotype, differentiation capacity, immunological features, and potential for homing. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2739–49. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meirelles Lda S, Fontes AM, Covas DT, Caplan AI. Mechanisms involved in the therapeutic properties of mesenchymal stem cells. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009;20:419–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vranken I, De Visscher G, Lebacq A, Verbeken E, Flameng W. The recruitment of primitive Lin(−) Sca-1(+), CD34(+), c-kit(+) and CD271(+) cells during the early intraperitoneal foreign body reaction. Biomaterials. 2008;29:797–808. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weissman IL, Shizuru JA. The origins of the identification and isolation of hematopoietic stem cells, and their capability to induce donor-specific transplantation tolerance and treat autoimmune diseases. Blood. 2008;112:3543–53. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-078220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wong SH, Lowes KN, Bertoncello I, Quigley AF, Simmons PJ, Cook MJ, Kornberg AJ, Kapsa RM. Evaluation of Sca-1 and c-Kit as selective markers for muscle remodelling by nonhemopoietic bone marrow cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1364–74. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bucala R, Spiegel LA, Chesney J, Hogan M, Cerami A. Circulating fibrocytes define a new leukocyte subpopulation that mediates tissue repair. Mol Med. 1994;1:71–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini F, Krause D, Deans R, Keating A, Prockop D, Horwitz E. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:315–7. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Horwitz EM, Le Blanc K, Dominici M, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini FC, Deans RJ, Krause DS, Keating A. Clarification of the nomenclature for MSC: The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2005;7:393–5. doi: 10.1080/14653240500319234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen Y, Ding D, Mao Z, He Y, Hu Y, Wu W, Jiang X. Synthesis of hydroxypropylcellulose-poly(acrylic acid) particles with semi-interpenetrating polymer network structure. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:2609–14. doi: 10.1021/bm800484e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.da Silva Meirelles L, Caplan AI, Nardi NB. In search of the in vivo identity of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2287–99. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gimble JM, Katz AJ, Bunnell BA. Adipose-derived stem cells for regenerative medicine. Circ Res. 2007;100:1249–60. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000265074.83288.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Anjos-Afonso F, Bonnet D. Nonhematopoietic/endothelial SSEA-1+ cells define the most primitive progenitors in the adult murine bone marrow mesenchymal compartment. Blood. 2007;109:1298–306. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-030551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Benzhi C, Limei Z, Ning W, Jiaqi L, Songling Z, Fanyu M, Hongyu Z, Yanjie L, Jing A, Baofeng Y. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells upregulate transient outward potassium currents in postnatal rat ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:41–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chavakis E, Urbich C, Dimmeler S. Homing and engraftment of progenitor cells: a prerequisite for cell therapy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;45:514–22. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chang JK, Li CJ, Wu SC, Yeh CH, Chen CH, Fu YC, Wang GJ, Ho ML. Effects of anti-inflammatory drugs on proliferation, cytotoxicity and osteogenesis in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:1371–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schroter A, Lustenberger RM, Obermair FJ, Thallmair M. High-dose corticosteroids after spinal cord injury reduce neural progenitor cell proliferation. Neuroscience. 2009;161:753–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Song IH, Caplan AI, Dennis JE. In vitro dexamethasone pretreatment enhances bone formation of human mesenchymal stem cells in vivo. J Orthop Res. 2009;27:916–21. doi: 10.1002/jor.20838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Aller MA, Arias JI, Arias J. Pathological axes of wound repair: gastrulation revisited. Theor Biol Med Model. 2010;7:37. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maurer M, von Stebut E. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:1882–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Murdoch C, Finn A. Chemokine receptors and their role in inflammation and infectious diseases. Blood. 2000;95:3032–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Suh W, Kim KL, Kim JM, Shin IS, Lee YS, Lee JY, Jang HS, Lee JS, Byun J, Choi JH, et al. Transplantation of endothelial progenitor cells accelerates dermal wound healing with increased recruitment of monocytes/macrophages and neovascularization. Stem Cells. 2005;23:1571–8. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lord BI, Woolford LB, Wood LM, Czaplewski LG, McCourt M, Hunter MG, Edwards RM. Mobilization of early hematopoietic progenitor cells with BB-10010: a genetically engineered variant of human macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha. Blood. 1995;85:3412–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pelus LM, Fukuda S. Peripheral blood stem cell mobilization: the CXCR2 ligand GRObeta rapidly mobilizes hematopoietic stem cells with enhanced engraftment properties. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:1010–20. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang F, Tsai S, Kato K, Yamanouchi D, Wang C, Rafii S, Liu B, Kent KC. Transforming growth factor-beta promotes recruitment of bone marrow cells and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells through stimulation of MCP-1 production in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:17564–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.013987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dudek AZ, Nesmelova I, Mayo K, Verfaillie CM, Pitchford S, Slungaard A. Platelet factor 4 promotes adhesion of hematopoietic progenitor cells and binds IL-8: novel mechanisms for modulation of hematopoiesis. Blood. 2003;101:4687–94. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang J, Lu SH, Liu YJ, Feng Y, Han ZC. Platelet factor 4 enhances the adhesion of normal and leukemic hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells to endothelial cells. Leuk Res. 2004;28:631–8. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2003.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Glennie S, Soeiro I, Dyson PJ, Lam EW, Dazzi F. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells induce division arrest anergy of activated T cells. Blood. 2005;105:2821–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]