1. Introduction

Animal studies have demonstrated that fetal exposure to some antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) at doses lower than those that result in structural malformations can produce cognitive and behavioral deficits, alter neurochemistry, and reduce brain weight [1,2]. Further, some AEDs, including clonazepam, diazepam, phenobarbital, phenytoin, vigabatrin, and valproate can produce widespread neuronal apoptosis in the immature rat brain similar to alcohol [3-9]. The effect is dose dependent, occurs at therapeutically relevant blood levels, and requires only relatively brief exposure (single injection). The effect has been related to reduced expression of neurotrophins and levels of protein kinases that promote neuronal growth and survival. These observations suggest that certain AEDs might produce similar adverse effects in children exposed in utero or in the neonatal period. In fact, some AEDs have been associated with reduced cognitive abilities (e.g., IQ) in children exposed in utero [10-12]. In a follow-up study [13] fetal valproate exposure was shown to significantly impair verbal as well as nonverbal abilities while carbamazepine significantly impacted only verbal abilities. Further, a dose dependent relationship was present for both lower verbal and non-verbal abilities with valproate and for lower verbal abilities with carbamazepine. In this report, we examine the effects of fetal AED exposure on motor, adaptive and emotional/behavioral functioning at 3 years of age in children of women with epilepsy.

2. Methods

2.1 Design

The Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (NEAD) study is a prospective observational study examining possible cognitive and behavioral teratogenesis of AEDs. We enrolled pregnant women with epilepsy who were on one of four AED monotherapies (i.e., carbamazepine, lamotrigine, phenytoin, or valproate) from October 1999 through February 2004 across 25 epilepsy centers in the USA and UK. These children are being followed to 6 years of age. We recently reported on IQ outcomes in these children at 3 years of age [12]. In a follow-up study we reported on verbal and nonverbal functioning in these same children [13]. In this paper we report on the motor, adaptive and emotional/behavioral outcomes at 3 years of age and examine dose-dependent effects.

2.2 Participants

Consent from participants was obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki. IRBs at each center approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained prior to enrollment. Pregnant women with epilepsy on carbamazepine, lamotrigine, phenytoin, or valproate monotherapy were enrolled. These four AED monotherapies were the most frequently employed during the enrollment time period. Other AEDs were not included because of insufficient numbers. Polytherapy was not included because of its association with poorer outcomes [14,15]. A non-exposed control group was not included at the direction of an NIH review panel. Mothers with IQ below 70 were excluded to avoid floor effects and because maternal IQ is the major predictor of child IQ in population studies [16]. Other exclusion criteria included positive syphilis or HIV serology, progressive cerebral disease, other major disease (e.g., diabetes), exposure to teratogenic agents other than AEDs, poor AED compliance, drug abuse in the prior year, or drug abuse sequelae.

2.3 Procedure

Information was collected on potentially confounding variables, including maternal IQ, age, education, employment, race, seizure/epilepsy types and frequency, AED dosages, compliance, socioeconomic status [17], UK/USA site, preconception folate use, use of alcohol, tobacco, or other drugs during pregnancy, unwanted pregnancy, abnormalities or complications in the present pregnancy or prior pregnancies, enrollment and birth gestational age, birth weight, breastfeeding, and childhood medical diseases. Children were classified as breastfed if they were currently breastfeeding at the time of the 3 month follow-up phone call after delivery. Because separate investigations with similar research designs in the US and UK were merged after the investigations were initiated, maternal IQs were assessed using different measures. These measures included the Test of Non-verbal Intelligence-3rd Edition (TONI-3) [18] in 267 mothers, Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) [19] in 20, and National Adult Reading Test (NART) [20] in 17. To allow for comparisons across AEDs, the dosages were standardized. Average AED dose during pregnancy was standardized relative to ranges observed within each group by the following calculation: 100 × (observed dose − minimum dose) ÷ range of doses.

Motor outcomes were evaluated by assessors (blinded to AED) using the Motor Scale from the Bayley Scales of Infant Development - Second Edition (BSID – II) [21]. In order to assess adaptive functioning, the child’s mother/father and preschool teacher/daycare worker (if child was attending) were asked to complete the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System – Second Edition (ABAS – II) [22]. Emotional/behavioral functioning was measured by having the child’s mother/father and preschool teacher/daycare worker complete the Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC) [23]. Due to the small number of children who were attending preschool/daycare only 46 teacher BASC forms and 50 teacher ABAS-II forms were completed and returned. As a result, it was decided to analyze the parent rating scales only. Finally, level of stress in the parent –child relationship was assessed by having the child’s mother/father complete the Parent Stress Index – Third Edition (PSI – III) [24]. The motor assessment and rating scale completion was conducted when the child was 36-45 months/old.

Training and monitoring of the neuropsychological evaluations were conducted to assure quality and consistency across sites. As part of the training, workshops were conducted for all neuropsychological test batteries annually. In addition, each assessor was required to identify errors and provide appropriate correction for videotaped testing sessions containing errors in administration and scoring. Assessors were also required to submit their own videotape of a practice test session (non-study child) with record forms to the Neuropsychology Core Director for review, feedback and approval. If assessors failed, they submitted additional video assessments for approval prior to testing study children.

2.4 Data Analysis

The primary analysis in this study included 229 children with complete motor, adaptive and/or emotional/behavioral assessment at 3 years/old. Outcome data were missing for 82 of the originally enrolled children. Multivariate regression models were used to examine group differences, adjusting for covariates. The a priori hypothesis for each dependent variable was that the specific AED, dose, and maternal IQ were important covariates, and thus these were included as predictors in a linear model with child motor performance, adaptive and emotional/behavioral ratings as outcomes. Other covariates were added individually to the model and covariates were included in a final model if found to be significant (p < .05), and if they did not exhibit collinearity with existing predictors. The effects of multiple additional covariates were also examined, which included: maternal age, race/ethnicity (Caucasian, African American, Hispanic/Latino, Other), alcohol use during pregnancy (yes/no), preconception folate use, gestational age at birth, epilepsy/seizure types, seizure frequency during pregnancy, education, employment, socioeconomic status, US/UK site, tobacco use during pregnancy, birth weight, unwanted pregnancy, breastfeeding, prior pregnancy birth defects and complications, present pregnancy complications, and AED compliance.

The dependent variables were the Motor Index score (Standard Score; mean = 100, standard deviation =15) from the BSID – II, the General Adaptive Composite score (Standard Score; mean = 100, standard deviation =15) from the ABAS – II, the individual Scale scores (T Score; mean = 50, standard deviation = 10) from the BASC, and the percentile scores from the Parent and Child Domains from the PSI – III.

Multivariate regression models were adjusted for AED group and other covariates found to be significant predictors in the linear model at the 0.05 level of significance. Secondary analyses examined the following: 1) relative relationships of AED exposures to child motor performance, adaptive and emotional/behavioral ratings; and 2) relationship of the significant covariates within each model to AED exposure. Analyses were performed at the NEAD Data and Statistical Center using SAS 9.2.

3. Results

The primary analysis included 223 mothers and 229 children (6 sets of twins). Baseline maternal characteristics are depicted in Table 1. This table also shows a comparison of baseline characteristics in these mothers with the 82 mothers of children who were excluded from the analysis due to missing data. Mothers who were excluded from analysis do not differ statistically on any of these characteristics from those who were included in the analysis. The statistical results for performance on the Motor Index of the BSID-II and the General Adaptive Composite score from the ABAS – II are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographics and IQ results for mothers of children included in analyses (complete data on BSID, GAC, and/or one or more of the subscales of the BASC)

| Antiepileptic Drug | All (mothers included in analysis) | Carbamazepine | Lamotrigine | Phenytoin | Valproate | Mothers of children with missing outcome data [p-value for difference from mothers included in analysis] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers (n) | 223 | 61 | 76 | 40 | 46 | 82 |

| Mean Maternal IQs (95% CI) | 98 (96:100) | 99 (95:103) | 101 (98:105) | 93 (88:99) | 95 (91:100) | 97 (94:101) [P=0.70] |

| Mean Maternal Ages (95% CI) | 30 (29:31) | 30 (29:32) | 31 (30:32) | 30 (28:32) | 29 (27:31) | 29 (28:30) [P=0.13] |

| Mean Dose A mg/day (95% CI) | N/A | 771 (667:875) | 473 (417:529) | 402 (361:442) | 1070 (876:1264) | N/A |

| Standardized Dose B (95% CI) | 35 (33:38) | 32 (27:36) | 36 (31:41) | 49 (43:55) | 27 (22:33) | 33 (28:37) [P=0.29] |

| Gestational Age weeks (95% CI) | 39 (39:39) | 38 (38:39) | 39 (39:40) | 38 (37:39) | 39 (39:40) | 39 (39:40) [P=0.23] |

| Preconception Folate n (%) | 128 (57) | 34 (56) | 45 (59) | 18 (45) | 31 (67) | 46 (56) [P=0.84] |

| Alcohol use during pregnancy n (%) | 17 (8) | 6 (10) | 6 (9) | 2 (5) | 4 (9) | 7 (9) [P=0.79] |

| Epilepsy Types D | ||||||

| Localization Related n (%) | 131 (59) | 52 (85) | 40 (53) | 29 (73) | 10 (22) | 53 (65) [P=0.35] |

| Idiopathic Generalized n (%) | 73 (33) | 5 (8) | 28 (37) | 7 (18) | 33 (72) | 24 (29) [P=0.56] |

| GTCS n (%) | 19 (9) | 4 (7) | 8 (11) | 4 (10) | 3 (7) | 5 (6) [P=0.49] |

| Race | ||||||

| Caucasian | 182 (82) | 49 (80) | 67 (88) | 25 (63) | 41 (89) | 63 (77) [P=0.35] |

| Black | 9 (4) | 4 (7) | 1 (1) | 3 (8) | 1 (2) | 5 (6) [P=0.45] |

| Hispanic | 19 (9) | 4 (7) | 3 (4) | 11 (27) | 1 (2) | 12 (15) [P=0.12] |

| Other | 13 (6) | 4 (7) | 5 (7) | 1 (2) | 3 (7) | 2 (2) [P=0.22] |

Average dose for pregnancy.

See Methods for description of how dosages were standardized.

Any alcohol use during pregnancy (yes/no)

Epilepsy types: Localization Related (includes cryptogenic and symptomatic); Idiopathic Generalized (includes absence, juvenile myoclonic, genetic, and other idiopathic generalized not otherwise classified); GTCS = generalized tonic clonic seizures (unknown if generalized or secondary generalized).

Table 2.

Analysis of Covariance Results

| Dependent Variable | Covariate | Estimate [95% Confidence Interval] | F-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSID – II Motor Index | AED Group (4 groups) | -- | 1.74 | 0.1608 |

| Maternal IQ | 0.14 [0.01:0.27] | 4.73 | 0.0310 | |

| Standardized Dose | -0.24 [-0.35:-0.13] | 19.26 | <.0001 | |

| Gestational Age | 1.34 [0.49:2.18] | 9.67 | 0.0022 | |

| Site in UK | -6.39 [-11.35:-1.42] | 6.45 | 0.0120 | |

| ABAS – II General Adaptive Composite | AED Group (4 groups) | -- | 1.59 | 0.1941 |

| Standardized Dose | -0.21 [-0.32:-0.11] | 17.47 | <.0001 | |

| Education Beyond HS | 7.63 [2.96:12.31] | 10.36 | 0.0015 |

3.1 Motor functioning

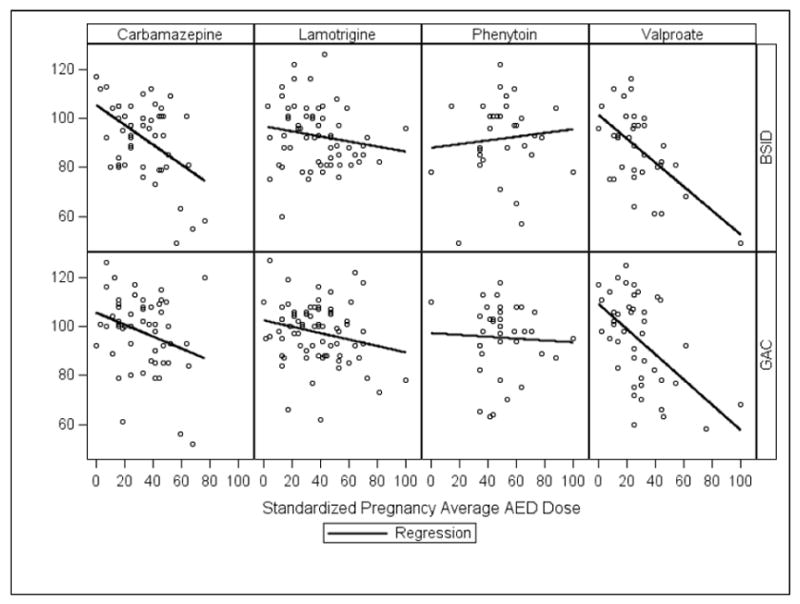

A summary of the analysis of covariance models is given in Table 2 and indicates that the adjusted mean performance scores of the four AED groups on the BSID-II Motor Index did not significantly differ. Adjusted age 3 mean Index scores along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each AED group are listed in Table 3. Maternal IQ, standardized AED dose, gestational age at delivery and site location (US vs. UK) were significantly related to performance on the BSID-II Motor Index. Partial Pearson correlations for maternal IQ and pregnancy average AED dose are listed in Table 4 and scatter plots of the dose dependent effects are depicted in Figure 1. Analysis of Table 4 indicates that higher maternal IQ was associated with higher Motor Index scores in the children whose mothers took phenytoin during pregnancy. A similar trend exists for lamotrigine. Dose dependent effects, when controlling for maternal IQ, were seen for valproate and carbamazepine which indicate that higher average dosages of both of these AEDs were associated with lower Motor Index scores. Finally, prematurity (<37 weeks) appeared to be associated with lower Motor Index scores; however, further inspection of group membership revealed that the number of preterm children in all of the AED groups was extremely small (n’s ranging from 2 in the valproate group to 6 in the carbamazepine group) making further analysis of AED group membership suspect. In addition, a t-test comparing Motor Index performance of premature children vs term children was not significant (p = 0.14).

Table 3.

Adjusted age 3 means (95% Confidence Intervals) for BSID – II Motor Index and ABAS – II General Adaptive Composite for each antiepileptic drug (AED).

| Carbamazepine | Lamotrigine | Phenytoin | Valproate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSID MotorA | 92.0 (89:96) | 91 (88:95) | 95 (90:100) | 87 (83:92) |

| ABAS GACB | 97 (93: 101) | 97 (93:100) | 100 (95:105) | 93 (89:97) |

Mean BSID – II Motor Index adjusted for maternal IQ, standardized dose, gestational age at birth, and site location (US/UK).

Mean ABAS – II General Adaptive Composite adjusted for standardized dose and maternal education beyond high school (yes/no).

Table 4.

a. Relationships of pregnancy average standardized dose to BSID – II Motor Index and to ABAS – II General Adaptive Composite, using Partial Pearson correlations (p-values), controlling for maternal IQ.

| Carbamazepine | Lamotrigine | Phenytoin | Valproate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSID |

-.47 (p=.0005) n=51 |

-.17 (p=.1954) n=62 |

.16 (p=.4030) n=32 |

-.60 (p=<.0001) n=38 |

| ABAS | -.26 (p=.0577) n=55 |

-.22 (p=.0688) n=72 |

-.05 (p=.7804) n=37 |

-.54 (p=.0002) n=44 |

| b. Relationships of maternal IQ to BSID – II Motor Index and to ABAS – II General Adaptive Composite using Pearson correlations (p-values) | ||||

| Carbamazepine | Lamotrigine | Phenytoin | Valproate | |

| BSID | .17 (p=.2329) n=51 |

.23 (p=.0665) n=62 |

.41 (p=.0189) n=32 |

.17 (p=.3178) n=38 |

| ABAS |

.31 (p=.0188) n=55 |

-.07 (p=.5833) n=72 |

.30 (p=.0728) n=37 |

-.03 (p=.8235) n=44 |

Figure 1.

Scatter plots of BSID-II Motor Index and ABAS-II General Adaptive Composite scores vs. standardized dose for each Antiepileptic Drug (AED) during pregnancy.

3.2 Adaptive Functioning

Results of analysis of covariance models depicted in Table 2 indicate that the adjusted mean performance ratings of the four AED groups on the ABAS-II (General Adaptive Composite score) did not significantly differ. Adjusted age 3 mean Composite scores along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each AED group are listed in Table 3. Standardized AED dose and maternal education beyond high school were significantly related to performance ratings on the ABAS-II. Partial Pearson correlations for standardized AED dose are presented in Table 4 and scatter plots of the dose dependent effects are depicted in Figure 1. Significant dose dependent effects, when controlling for maternal IQ, were seen for valproate and marginally significant effects were seen for carbamazepine which indicated that higher average dosages of both of these AEDs were associated with lower adaptive performance ratings of the children whose mothers took these AEDs during their pregnancies. Since maternal education beyond high school is a categorical variable a Chi-Square test was performed to further delineate the relationship of this covariate to adaptive functioning. Results indicate that adaptive ratings were significantly higher (p = < .001) in children whose mothers received education beyond high school. The adjusted mean score for children of mothers who were educated beyond high school was 98.6 (95% CI = 96.4:100.9) vs. 90.6 (95% CI = 86.7:94.6) for the children of mothers with a high school education or less.

3.3 Emotional/behavioral Functioning

Results of the analysis of covariance models for the 10 BASC Scales in Table 5 indicate that the adjusted mean performance ratings of the four AED groups across the 10 BASC Scales did not significantly differ. Adjusted age 3 mean BASC Scale scores along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each AED group are listed in Table 6. Further analysis in Table 5 indicates that gestational age is associated with parent ratings on the Somatization Scale. Specifically, follow-up Chi-Square tests indicate that parents of preterm (<37 weeks) children endorsed significantly (p = 0.01) more somatic/medical complaints than parents of full-term children. In addition, ratings on the Social Skills Scale were associated with standardized AED dose. Follow-up Partial Pearson correlation revealed a dose dependent effect for valproate (r = -0.46; p = .002) which indicated that parents reported increasing problems with their child’s social skills with higher average doses of Valproate during pregnancy.

Table 5.

Summary of ANCOVA Models for the 10 BASC Subscales

| Dependent Variable | Covariate | F Value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperactivity | AED Group (4 groups) | 1.16 | 0.3274 |

| Maternal IQ | 0.36 | 0.5476 | |

| Standardized Dose | 0.07 | 0.7886 | |

| Maternal Age | 0.02 | 0.8815 | |

| Gestational Age | 0.53 | 0.4687 | |

| Preconception Folate Use | 2.07 | 0.1521 | |

| Aggression | AED Group (4 groups) | 1.32 | 0.2683 |

| Maternal IQ | 0.00 | 0.9820 | |

| Standardized Dose | 0.48 | 0.4914 | |

| Maternal Age | 2.22 | 0.1374 | |

| Gestational Age | 1.22 | 0.2699 | |

| Preconception Folate Use | 0.28 | 0.5956 | |

| Anxiety | AED Group (4 groups) | 2.25 | 0.0833 |

| Maternal IQ | 0.14 | 0.7123 | |

| Standardized Dose | 0.90 | 0.3427 | |

| Maternal Age | 0.36 | 0.5493 | |

| Gestational Age | 0.02 | 0.8979 | |

| Preconception Folate Use | 0.19 | 0.6601 | |

| Depression | AED Group (4 groups) | 0.46 | 0.7126 |

| Maternal IQ | 0.05 | 0.8176 | |

| Standardized Dose | 0.41 | 0.5234 | |

| Maternal Age | 1.02 | 0.3126 | |

| Gestational Age | 0.18 | 0.6702 | |

| Preconception Folate Use | 1.19 | 0.2768 | |

| Somatization | AED Group (4 groups) | 0.03 | 0.9918 |

| Maternal IQ | 0.08 | 0.7764 | |

| Standardized Dose | 0.03 | 0.8574 | |

| Maternal Age | 0.01 | 0.9183 | |

| Gestational Age | 8.96 | 0.0031 | |

| Preconception Folate Use | 2.46 | 0.1187 | |

| Atypicality | AED Group (4 groups) | 1.84 | 0.1411 |

| Maternal IQ | 1.69 | 0.1949 | |

| Standardized Dose | 0.37 | 0.5453 | |

| Maternal Age | 0.98 | 0.3235 | |

| Gestational Age | 0.19 | 0.6636 | |

| Preconception Folate Use | 0.97 | 0.3249 | |

| Withdrawal | AED Group (4 groups) | 0.12 | 0.9511 |

| Maternal IQ | 0.23 | 0.6330 | |

| Standardized Dose | 0.01 | 0.9210 | |

| Maternal Age | 1.18 | 0.2792 | |

| Gestational Age | 1.62 | 0.2040 | |

| Preconception Folate Use | 1.93 | 0.1667 | |

| Attention Problems | AED Group (4 groups) | 1.03 | 0.3816 |

| Maternal IQ | 0.39 | 0.5307 | |

| Standardized Dose | 3.13 | 0.0784 | |

| Maternal Age | 1.18 | 0.2779 | |

| Gestational Age | 0.32 | 0.5728 | |

| Preconception Folate Use | 1.50 | 0.2227 | |

| Adaptability | AED Group (4 groups) | 1.00 | 0.3947 |

| Maternal IQ | 0.54 | 0.4641 | |

| Standardized Dose | 0.03 | 0.8569 | |

| Maternal Age | 4.90 | 0.0279 | |

| Gestational Age | 0.04 | 0.8460 | |

| Preconception Folate Use | 0.05 | 0.8273 | |

| Social Skills | AED Group (4 groups) | 1.68 | 0.1715 |

| Maternal IQ | 3.28 | 0.0715 | |

| Standardized Dose | 9.26 | 0.0027 | |

| Maternal Age | 0.67 | 0.4131 | |

| Gestational Age | 0.03 | 0.8699 | |

| Preconception Folate Use | 0.80 | 0.3711 |

Table 6.

Adjusted means (95% Confidence Intervals) for 10 BASC subscales for each antiepileptic drug (AED).

| Carbamazepine | Lamotrigine | Phenytoin | Valproate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperactivity | 48 (46:51) | 48 (46:50) | 52 (48:55) | 49 (46:52) |

| Aggression | 47 (44: 49) | 47 (45:50) | 49 (46:52) | 45 (42:47) |

| Anxiety | 47 (45:50) | 47 (45:49) | 50 (47:53) | 45 (42:48) |

| Depression | 47 (45:50) | 47 (45:49) | 49 (45:52) | 46 (43:49) |

| Somatization | 48 (46:51) | 48 (46:50) | 49 (46:52) | 49 (46:51) |

| Atypicality | 48 (46:51) | 49 (47:51) | 51 (48:54) | 52 (49:55) |

| Withdrawal | 51 (48:53) | 50 (48:52) | 50 (47:54) | 49 (46:53) |

| Attention Problems | 51 (47:54) | 49 (46:51) | 50 (46:54) | 53 (49:56) |

| Adaptability | 51 (48:54) | 52 (49:55) | 48 (44:52) | 52 (48:55) |

| Social Skills | 49 (46:51) | 51 (49:54) | 51 (47:55) | 47 (44:50) |

Mean adjusted for maternal IQ, standardized dose, gestational age at birth, and maternal age and preconception folate.

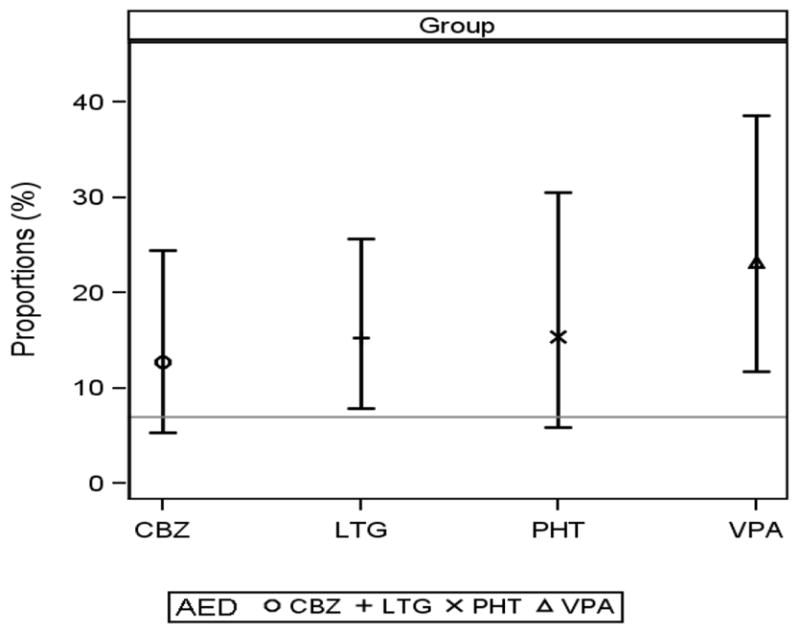

In order to evaluate the frequency of children who may be a risk for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD: both inattentive and combined types), the frequency/percent of children with at risk parent ratings on the Inattention Scale of the BASC (inattentive type) and at risk ratings on both the Inattention and Hyperactivity Scales (combined type) was calculated for each AED group. An at risk score was defined as being greater than one standard deviation above the mean for the standardization sample (t score > 60). The frequency/percent in each AED group was compared with the 7% estimate of ADHD in the U.S. population reported in the 2006 National Health Interview Survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [25]. This figure was based upon parental endorsement of ADHD in their children 3-17 years of age. Paired t-test analysis indicated that only the valproate group (23.3%; p = .02) had a significantly greater percent of children at risk for ADHD than the national CDC estimate (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percent of Children at Risk for ADHD by AED Group

Note: The horizontal line depicts the 7% estimate of ADHD in the U.S. population reported in the 2006 National Health Interview Survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [25].

In order to determine if the AED groups significantly differed on the frequency of parents reporting elevated levels of stress in the parent–child relationship, the frequency/percent of children with at risk parent ratings on the Parent and Child Domains from the PSI-III were calculated for each AED group. At risk scores were defined as being greater than the 90th percentile. Fisher’s exact testing indicated no significant group differences for the Parent Domain (p = .07) or the Child Domain (p = .24).

4. Discussion

The NEAD Study is an ongoing prospective observational multicenter study in the USA and UK, which has enrolled pregnant women with epilepsy on AED monotherapy from 1999 to 2004. The study seeks to determine if differential long-term neurodevelopmental effects exist across four commonly used AEDs (carbamazepine, lamotrigine, phenytoin, or valproate). In this report, we examined the effects of fetal AED exposure on motor, adaptive and emotional/behavioral functioning at 3 years of age in children of women with epilepsy.

The major results of this study indicate that although adjusted mean scores for the four AED groups were in the low average to average range for motor functioning, adaptive functioning, and parental ratings of emotional/behavioral functioning, a significant dose related performance decline in motor functioning was seen for both valproate and carbamazepine. A significant dose related performance decline in parental ratings of adaptive functioning was also seen for valproate with a marginal performance decline evident for carbamazepine. Further, parents endorsed a significant decline in social skills for valproate that was dose related. Finally, based upon parent ratings of attention span and hyperactivity, children of mothers who took valproate during their pregnancy may be at a significantly greater risk for a future diagnosis of ADHD.

These results present the first evidence that motor and adaptive functioning outcomes may be reduced in children exposed in utero to higher dosages of valproate and carbamazepine compared to lamotrigine, and phenytoin. In addition, the finding of an increased risk of a future diagnosis of ADHD in children whose mothers took valproate during their pregnancy supports prior studies demonstrating that children exposed to valproate in utero may be at increase risk for behavioral abnormalities as well [26-28].

The strengths of our study include its prospective design, blinded cognitive assessments using standardized measures, and detailed monitoring of multiple potential confounding factors. However, caution is advised due to study limitations which include a relatively small sample size, loss of enrolled subjects to analysis, lack of randomization, lack of AED blood levels, absence of an unexposed control group during pregnancy, and the relatively young age of the children at this planned interim analysis. Because the NEAD study is not a randomized trial, it is possible that confounding factors related to baseline characteristics may have affected the results. For example, while epilepsy/seizure type was not found to be a significant outcome predictor, data on additional factors which could influence medication choice, such as medication cost, and whether or not the mother had previously failed another AED prior to being placed on the medication taken during her pregnancy, were not collected and studied as part of this investigation.

Based upon these findings, a raised index of suspicion should translate into more careful follow-up and evaluation of these children with appropriate referral for interventional therapies when indicated. Additional research is needed to confirm these findings, examine risks of other AEDs, define the risks associated with AEDs in the neonate for treatment of seizures, and to understand the underlying mechanisms of adverse AED effects on the immature brain.

Research Highlights.

-

➢

Children exposed in utero to higher dosages of valproate have lower motor/adaptive functioning

-

➢

Children exposed in utero to higher dosages of carbamazepine have lower motor/adaptive functioning

-

➢

Children exposed in utero to valproate may be at Increased risk for ADHD

Acknowledgments

The investigators would like to thank the children and families who have given their time to participate in the NEAD Study.

Funding. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [2RO1-NS038455 to K.M., R01NS050659 to N.B.] and the United Kingdom Epilepsy Research Foundation [RB219738 to G.B].

Appendix

NEAD Study Group

Arizona Health Sciences Center, Tucson, Arizona: David Labiner MD Jennifer Moon PhD, Scott Sherman MD; Baylor Medical Center, Irving Texas: Deborah T. Combs Cantrell MD, University of Texas-Southwestern, Dallas Texas: Cheryl Silver PhD; Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio: Monisha Goyal MD, Mike R. Schoenberg PhD; Columbia University, New York City, NY: Alison Pack MD, Christina Palmese, Ph.D, Joyce Echo, Ph.D; Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia: Kimford J. Meador MD, David Loring PhD, Page Pennell MD, Daniel Drane PhD, Eugene Moore BS, Megan Denham MAEd, Charles Epstein MD, Jennifer Gess PhD, Sandra Helmers MD, Thomas Henry MD; Georgetown University, Washington, DC: Gholam Motamedi MD, Erin Flax BS; Harvard- Brigham & Women’s, Boston, Massachusetts: Edward Bromfield MD, Katrina Boyer PhD, Barbara Dworetzky ScB, MD; Harvard – Massachusetts General, Boston, Massachusetts: Andrew Cole MD, Lucila Halperin BA, Sara Shavel-Jessop BA; Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, Michigan: Gregory Barkley MD, Barbara Moir MS; Medical College of Cornell University, New York City, New York: Cynthia Harden MD, Tara Tamny-Young PhD; Medical College of Georgia, Augusta, Georgia: Gregory Lee PhD, Morris Cohen EdD; Minnesota Epilepsy Group, St. Paul, Minnesota: Patricia Penovich MD, Donna Minter EdD; Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio: Layne Moore MD, Kathryn Murdock MA; Riddle Health Care, Media, Pennsylvania: Joyce Liporace MD, Kathryn Wilcox, BS; Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois: Andres Kanner MD, Michael N. Nelson PhD; The Comprehensive Epilepsy Care Center for Children and Adults, St. Louis, Missouri: William Rosenfeld MD, Michelle Meyer MEd; St. Mary’s Hospital, Manchester, England: Jill Clayton-Smith MD, George Mawer MD, Usha Kini MD; University Alabama, Birmingham, Alabama: Roy Martin PhD; University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio: Michael Privitera MD, Jennifer Bellman PsyD, David Ficker MD; University of Kansas School of Medicine - Wichita, Wichita, Kansas: Lyle Baade PhD, Kore Liow MD; University of Liverpool, Liverpool, England: David Chadwick MD, Gus Baker PhD, Alison Booth BSc, Rebecca Bromley BSc, Sara Dutton BSc, James Kelly BSc, Jenna Mallows BSc, Lauren McEwan MSc, Laura Purdy BSC; University of Miami, Miami, Florida: Eugene Ramsay MD, Patricia Arena PhD; University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California: Laura Kalayjian MD, Christianne Heck MD, Sonia Padilla PsyD; University of Washington, Seattle, Washington: John Miller MD, Gail Rosenbaum BA, Alan Wilensky MD; University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah: Tawnya Constantino MD, Julien Smith PhD; Walton Centre for Neurology & Neurosurgery, Liverpool, England: Naghme Adab, MD, Gisela Veling-Warnke MD; Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, North Carolina: Maria Sam MD, Cormac O’Donovan MD, Cecile Naylor PhD, Shelli Nobles MS, Cesar Santos MD. Executive Committee: Dartmouth Medical School, Hanover, New Hampshire: Gregory L. Holmes MD; Stanford University, Stanford, California: Maurice Druzin MD, Martha Morrell MD, Lorene Nelson PhD; Texas A & M University Health Science Center, Houston, Texas: Richard Finnell PhD; University of Oregon, Portland, Oregon: Mark Yerby MD; University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario: Khosrow Adeli PhD, Peter Wells Pharm.D. Data and Statistical Center: EMMES Corporation, Rockville, Maryland: Temperance Blalock AA, Nancy Browning PhD, Todd Crawford MS, Linda Hendrickson, Bernadette Jolles MA, Meghan Kelly Kunchai MPH, Hayley Loblein BS, Yinka Ogunsola BS, Steve Russell BS, Jamie Winestone BS, Mark Wolff PhD, Phyllis Zaia BS, Thad Zajdowicz MD, MPH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fisher JE, Vorhees CV. Developmental toxicity of antiepileptic drugs: relationship to postnatal dysfunction. Pharmacol Res. 1992;26(3):207–21. doi: 10.1016/1043-6618(92)90210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaily E, Meador KJ. Neurodevelopmental effects. In: Engel J, Pedley TA, editors. Epilepsy: a comprehensive textbook. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 1225–33. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bittigau P, Sifringer M, Genz K, Reith E, Pospischil D, Govindarajalu S, et al. Antiepileptic drugs and apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(23):15089–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222550499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bittigau P, Sifringer M, Ikonomidou C. Antiepileptic drugs and apoptosis in the developing brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;993:103–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07517.x. discussion 23-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glier C, Dzietko M, Bittigau P, Jarosz B, Korobowicz E, Ikonomidou C. Therapeutic doses of topiramate are not toxic to the developing rat brain. Exp Neurol. 2004;187(2):403–9. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katz I, Kim J, Gale K, Kondratyev A. Effects of lamotrigine alone and in combination with MK-801, phenobarbital, or phenytoin on cell death in the neonatal rat brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322(2):494–500. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.123133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JS, Kondratyev A, Tomita Y, Gale K. Neurodevelopmental impact of antiepileptic drugs and seizures in the immature brain. Epilepsia. 2007;48(Suppl 5):19–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manthey D, Asimiadou S, Stefovska V, Kaindl AM, Fassbender J, Ikonomidou C, et al. Sulthiame but not levetiracetam exerts neurotoxic effect in the developing rat brain. Exp Neurol. 2005;193(2):497–503. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stefovska VG, Uckermann O, Czuczwar M, Smitka M, Czuczwar P, Kis J, et al. Sedative and anticonvulsant drugs suppress postnatal neurogenesis. Ann Neurol. 2008;64(4):434–45. doi: 10.1002/ana.21463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adab N, Kini U, Vinten J, Ayres J, Baker G, Clayton-Smith J, et al. The longer term outcome of children born to mothers with epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(11):1575–83. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.029132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaily E, Kantola-Sorsa E, Hiilesmaa V, Isoaho M, Matila R, Kotila M, et al. Normal intelligence in children with prenatal exposure to carbamazepine. Neurology. 2004;62(1):28–32. doi: 10.1212/wnl.62.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, Clayton-Smith J, Combs-Cantrell DT, Cohen MJ, et al. Cognitive function at 3 years of age after fetal exposure to antiepileptic drugs. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(16):1597–605. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, Cohen MJ, Clayton-Smith J, et al. Fetal Antiepileptic Drug Exposure and Verbal vs. Nonverbal Abilities at Age 3. Brain. 2011;134:396–404. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kluger BM, Meador KJ. Teratogenicity of antiepileptic medications. Semin Neurol. 2008;28(3):328–35. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1079337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harden CL, Meador KJ, Pennell PB, Hauser WA, Gronseth GS, French JA, et al. Practice Parameter update: Management issues for women with epilepsy--focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): Teratogenesis and perinatal outcomes. Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee and Therapeutics and Technology Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2009;73(2):133–41. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a6b312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sattler JM. Assessment of Children. 3. San Diego: Jerome M Sattler Pub., Inc.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hollingshead AB. Four factor index of social status. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown L, Sherbenou RJ, Johnsen SK. Test of Non-verbal Intelligence (TONI-3) 3. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wechsler D. Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence (WASI) San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson H, Willison J. National adult reading test (NART) Oxford, England: NFER-Nelson Publishing; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development. 2. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harrison PL, Oakland T. Adaptive Behavior Assessment System – II. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reynolds C, Kamphaus RW. Behavior Assessment System for Children. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abidin RR. Parenting Stress Index. Third Edition. Lutz, Fla.: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bloom B, Cohen RA. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2007. Summary Health Statistics for U.S. Children: National Health Interview Survey, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bromley RL, Mawer G, Clayton-Smith J, Baker GA. Autism spectrum disorders following in utero exposure to antiepileptic drugs. Neurology. 2008;71(23):1923–4. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000339399.64213.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vinten J, Bromley RL, Taylor J, Adab N, Kini U, Baker GA. The behavioral consequences of exposure to antiepileptic drugs in utero. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;14(1):197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams G, King J, Cunningham M, Stephan M, Kerr B, Hersh JH. Fetal valproate syndrome and autism: additional evidence of an association. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43(3):202–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]