Abstract

The self-esteem of some people with serious psychiatric disorders may be hurt by internalizing stereotypes about mental illness. A progressive model of self-stigma yields four stages leading to diminished self-esteem and hope: being aware of associated stereotypes, agreeing with them, applying the stereotypes to one's self, and suffering lower self-esteem. We expect to find associations between proximal stages -- awareness and agreement -- to be greater than between more distal stages: awareness and harm. The model was tested on 85 people with schizophrenia or other serious mental illnesses who completed measures representing the four stages of self-stigma, another independently-developed instrument representing self-stigma, proxies of harm (lowered self-esteem and hopelessness), and depression. These measures were also repeated at 6-month follow-up. Results were mixed but some evidence supported the progressive nature of self-stigma. Most importantly, separate stages of the progressive model were significantly associated with lowered self-esteem and hope. Implications of the model for stigma change are discussed.

Keywords: self-stigma, Self-Stigma of Mental Illness Scale, Hope

1. Introduction

Stigma challenges many people with serious mental illnesses sometimes harming their sense of hope and self-esteem. Social psychological models describe stigma as comprising stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination, a paradigm useful for the goals of this study. Stereotypes are harmful beliefs about groups of people and are unavoidably learned when maturing in a culture (Crocker & Major, 2003; Dovidio et al., 2000). Stereotypes commonly identified about people with serious mental illness include dangerousness, blame, and social incompetence (Corrigan, 2005). Prejudice is agreeing with the stereotype -- “That's right. People with mental illness are dangerous.” -- and emotionally reacting – “and so, the dangerous guy with mental illness scares me.” Discrimination is the behavioral response to prejudice. “And because the guy is mentally ill and dangerous, I am going to avoid him. For example, I am not going to hire him to work in my company.” Stigma seems to harm people with serious mental illness in several ways. Public stigma (the discrimination directed against people with mental illness by individuals from the general population who endorse related stereotypes) has been distinguished from self-stigma (the harm to self-esteem that results from internalizing stereotypes) in the research literature; the latter is the focus of this paper. (Corrigan & Watson, 2002; Link & Phelan, 2001).

Some studies have sought to conceptualize stereotypes that comprise self-stigma. Ritsher and colleagues (Ritsher et al., 2003; Ritsher & Phelan, 2004) developed a five factor scale to do this: alienation (the subjective experience of being less than a full member of society or having a ‘spoiled identity’), stereotype endorsement (the degree to which respondents agree with common stereotypes), discrimination experience (perception of the way respondents believe they are treated negatively by others), social withdrawal (the degree to which the respondent avoids others to escape rejection), and stigma resistance (the experience of resisting or being unaffected by stigma). Ritsher's model was informed by the Perceived Devaluation-Discrimination Questionnaire (PDDQ; Link, 1987) which assessed whether people with mental illness are aware or can otherwise recognize the stereotypes of mental illness. Work on perceived devaluation-discrimination implied self-stigma to be a progressive phenomenon (Corrigan et al., 2006; Watson et al., 2007). Awareness is the first of several stages that lead to the ultimate harm of self-stigma. After awareness is agreement; the person with serious mental illness believes the stereotype is true. Agreement leads to application; believing the stereotype is descriptive of one's self. Applying stigma to one's self is similar to what Link (1987) called internalizing stigma. Research has specifically shown applying the stigma leads to harm: diminished self-esteem, for example (Corrigan et al., 2006). One way to support the progressive model is to determine whether early stages like awareness uniquely correlate with an independent measure of stigma that focuses solely on perception. We included the PDDQ in our study in order to triangulate analyses and test this independence.

Self-stigma seems to be experienced by many people with serious mental illnesses with more than one fifth of people with affective disorders (Brohan et al., 2010b) and one half of people with schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders (Brohan et al., 2010a) reporting it at moderate to high levels. Still, it is important to realize that not everyone with serious mental illness will internalize stigma. Some show righteous indignation at public stigma frequently joining advocacy efforts as a result (Rogers et al., 1997). Many are unaware of self-stigma and its impact altogether. Basic information about self-stigma will be important for developing strategies to impact it, strategies which are discussed more fully in the Discussion section of this paper.

The harm of self-stigma manifests itself in several ways (Corrigan et al., 2006; Livingston et al., 2011; Watson et al., 2007). It diminishes self esteem and feelings of self-worth which undermines hope and optimism in achieving goals. A progressive model of self-esteem suggests results of one stage are most influenced by the stage immediately preceding it. This may explain why significant predictions between scales representing awareness of stigma and of harm are sometimes not found while those between adjacent scales for applying stigma to self and for harm more typically emerge. One of the difficulties of examining the progressive model and harm is sorting out the effects of self-stigma from those of depression because symptoms of depression fundamentally lead to diminished self-esteem. We attempt to examine this assertion by controlling regression analyses in this paper with a measure of depression.

The goal of the study described herein is to show scores representing proximal stages are believed to be most highly correlated. Even more, we expect to show negative effects of self-stigma on self-esteem are more associated with applying the stigmatizing belief to one's self rather than just being aware of the stereotype. We attempted to examine causal models in this paper by examining relationships overtime.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Eighty-five persons with schizophrenia or other psychiatric disorders were recruited at mental health service centers in the Chicago area; this sample size yields a power estimate over 0.90. Reported here are findings from a subset of the data from the larger study on the effects of implicit and explicit public and self-stigma of mental illness (Rüsch et al., 2009). The overall study had IRB approval and research participants were fully informed to the study. Research participants had at least an eighth grade reading level as assessed by the Wide Range Achievement Test (Wilkinson & Robertson, 2006). Participants were, on average, 44.8 years old (SD=9.7), had a mean of 13.5 years of education (SD=2.3), and were 68% male. More than half (58%) were African American and about a third (34%) Caucasian, while a few reported Latino (5%), and mixed or other ethnicities (4%). Axis I diagnoses were made using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan et al., 1998) based on DSM-IV criteria. Twenty-three (27%) participants had schizophrenia, 22 (26%) schizoaffective disorder, 30 (35%) bipolar disorder, and 10 (12%) recurrent unipolar major depressive disorder.

2.2 Procedure

At baseline (Time 1), subjects completed self-report measures, which were administered in face-to-face interviews. A selection of these measures was repeated six months later; 75 of the 85 research participants completed follow-up measures. Self-stigma progression was assessed using the forty item Self Stigma of Mental Illness Scale (SSMIS; Corrigan et al., 2006; Watson et al., 2007). The measure is divided into four subscales representing awareness (“I think the public believes most persons with mental illness cannot be trusted.”), agreement (“I think most persons with mental illness are to blame for their problems.”), application (“Because I have a mental illness, I am unable to take care of myself.”), and harm to self-esteem (“I currently respect myself less because I will not recover or get better.”). The scale has excellent internal consistency and concurrent validity (Corrigan et al., 2006; Watson et al., 2007). Research participants responded to all items using a 9 point agreement scale (9=strongly agree). Total scores were determined for each of the four factors with higher scores indicating greater endorsement of self-stigma as indicated by that factor; they range from 10 to 90.

Awareness of stereotypes was independently assessed using the 12-item Perceived Devaluation-Discrimination Questionnaire (PDDQ; Link & Phelan, 2001; Link et al., 1997; Perlick et al., 2001). Items include, for example, “Most people think less of a person who has been in a mental hospital.” Each statement is rated on a 6-point scale with 6 equal to “very strongly agree.” Higher scales represent greater awareness of stereotypes. The scale has excellent psychometric properties and has been shown to predict deterioration in self-esteem and increased depression (Link & Phelan, 2001; Link et al., 1997). Internal consistency for baseline data presented here is 0.85. The Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Scale (ISMIS) is a measure of Ritsher's model and contains 29 Likert items rated on a 4-point agreement scale (4 equal “strongly agree”.) The ISMIS has five subscales: alienation, stereotype endorsement, discrimination experience, social withdrawal, and stigma resistance (Ritsher, Otilingam, & Grajales, 2003; Ritsher, & Phelan, 2004). The first four of the five factors have good test-retest reliability and internal consistency and hence were used in the study; noticeably lower indices were found for stigma resistance. Note, however, that neither the five nor the four factor solutions have been clearly supported by exploratory or confirmatory factor analyses. Internal consistency from the baseline data for the first four factors ranged from 0.70 to 0.86. We included the ISMIS because factors represent the personal application of stereotypes to the self.

Outcomes of self-stigma were measured as change in self-esteem or hope. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES), a widely used measure of self-esteem, consists of ten items such as “I feel that I'm a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others.” For purposes of the analyses in this paper, the higher the RSES score, the lower the self esteem. Research participants responded to items using a four point Likert scale of agreement (4 means “strongly disagree”). Items were totaled into a single overall scale which has been previously shown to have good internal consistency in a sample of people with serious mental illness (Corrigan et al., 2006). RSES internal consistency from our data at baseline was 0.88. Low self-esteem is expected to diminish hope which was assessed in this study using the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS; Beck et al., 1974; Steed, 2001). It is a twenty item scale that represents life expectancies. The BHS comprised eleven negatively phrased and nine positively phrased items to which participants respond with a five point agreement scale (5 is strongly disagree). The overall scale score ranged from 20 to 100; for this study, the higher the BHS score, the lower the hope. The instrument has shown excellent reliability and construct validity (McMillan et al., 2007). Internal consistency was 0.92 at baseline. Depression clearly influences self-esteem and hope. The important question then, is whether the association between self-stigma indices and self-esteem/hope remain significant after shared variance between depression and self-esteem/hope is partialled out of the analyses. Depressed symptoms were measured using the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale CES-D (Radloff, 1977), with higher scores representing higher levels of depression (Cronbach's baseline alpha=0.92).

3. Results

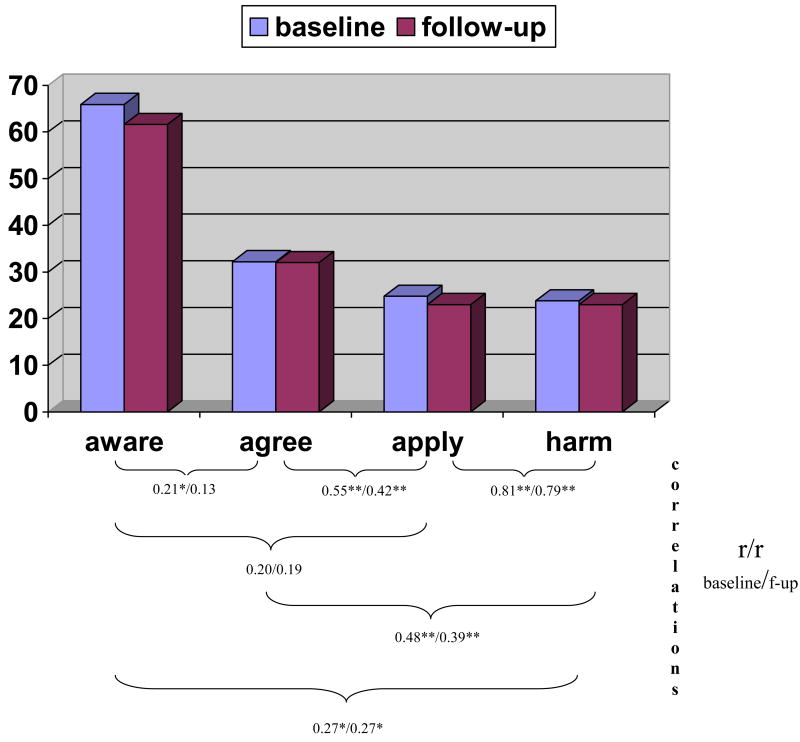

Baseline and follow-up data for the SSMIS and ISMIS were used to produce a correlation matrix to test the validity of our model. Baseline measurement from the SSMIS, PDDQ, ISMIS, and CESD were incorporated into separate regression analyses predicting baseline and follow-up self-esteem and hope. We first tested two hypotheses consistent with a progressive model of self-stigma. Figure 1 provides the statistics that test these hypotheses. First, consider the progressive model as trickle down in nature. More specifically, endorsing items related to applying a stereotype to one's self must be preceded by higher scores in agreeing with the stereotype which must, in turn, be preceded by awareness of the stereotype. The assumption is partially supported in the top half of Figure 1 that provides means of the four factors at baseline and follow-up. Overall differences are significant (for baseline (F(3,82)=125.9, P<0.001; for follow-up (F(3,72)=97.0, P<0.001). The largest endorsement score was found for the aware scale; it is significantly higher than agreement, next in the progression for both baseline (F(1,134)=304.4, P<0.001) and follow-up (F(1,74)=139.4, P<0.001). Difference between agree and apply scores were also significant for baseline (F(1,84)=23.9, P<0.001) and follow-up (F(1,74)=29.9, P<0.001). No significant differences were found between apply and harm scale scores. Difference in effect size is also notable. Greatest change is seen from awareness to agreement (eta squared=0.82 and 0.80 for baseline and follow-up respectively), which suggests fairly large and robust difference in being aware of a stereotype versus agreeing with it. A smaller effect size was found for the difference between agree and apply scales (eta squared=0.22 and 0.29).

Figure 1.

Means of SSMIS factors at baseline and follow-up. Factor scores range from 10 to 90. Below the graph are Pearson Product Moment Correlations (r/r) representing associations between the four factors at baseline and follow-up.

A second prediction based on the progressive model is cross scale correlations will be larger for scales representing proximal (e.g., aware to agree) versus relatively distant (aware to harm) stages. Pearson product moment correlations representing relationships by scale are summarized at the bottom of Figure 1 for baseline and follow-up data. Hypotheses are partially supported. Immediately proximal correlations are high for agree/apply (0.55/0.42 accounting for 30.2/17.6 percent of the variance respectively) and for apply/harm (0.81/0.79 which is 65.6/62.4 percent of the variance). The midrange association between agree and harm is smaller (0.48/0.39) than the first degree though these differences are significant. The most distant stages yielded even lower correlations (0.27/0.27). An exception to the findings is the relationship between awareness and the other two stages. Three out of four were nonsignificant.

Table 1 tests our hypotheses about the relationship between the proxies of self-stigma -- SSMIS, ISMIS, and PDDQ -- and outcome; assessed by the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) and the Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale (RSES). Results were presented separately here for baseline and follow-up, hope and self-esteem dependent variables. The SSMIS, ISMIS, PDDQ variables only represented baseline responses because relationships between stigma variable baseline and hope/self-esteem follow-up better reflect causal processes. The three sets of stigma measures were entered into the equations as three separate blocks: SSMIS, ISMIS plus PDDQ, and used in all three analyses. We added a fourth block that included the CES-D index of depression.

Table 1.

Multiple Regression with four blocks of variables examining relationship between the Self Stigma of Mental Illness Scale (SSMIS) factors and related constructs (ISMIS and PDDQ)with baseline and follow-up indices of hope (Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS)) and self-esteem (Rosenberg Self Esteem (RSES) scale.

| DEPENDENT VARIABLE∷ Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS), BASELINE BLOCK 1 N= 85; R2=0.32, p<0.001 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INDEPENDENT VARIABLES (all baseline) | B | SE B | β | t | p |

| SSMIS awareness | 0.06 | 0.072 | 0.086 | 0.881 | 0.381 |

| SSMIS agreement | 0.17 | 0.085 | 0.226 | 2.007 | 0.048 |

| SSMIS apply | 0.44 | 0.165 | 0.445 | 2.684 | 0.009 |

| SSMIS harm to self-esteem | 0.20 | 0.142 | 0.221 | 1.392 | 0.168 |

| BLOCK 2 R2=0.32, n.s. | |||||

| SSMIS awareness | 0.05 | 0.079 | 0.063 | 0.586 | 0.560 |

| SSMIS agreement | 0.17 | 0.086 | 0.224 | 1.978 | 0.051 |

| SSMIS apply | 0.45 | 0.166 | 0.448 | 2.691 | 0.009 |

| SSMIS harm to self-esteem | 0.18 | 0.148 | 0.198 | 1.196 | 0.235 |

| PDDQ_perceived stigma | 0.97 | 1.781 | 0.061 | 0.544 | 0.588 |

| BLOCK 3 R2=0.48, p<0.001 | |||||

| SSMIS awareness | 0.03 | 0.077 | 0.044 | 0.418 | 0.677 |

| SSMIS agreement | 0.19 | 0.084 | 0.255 | 2.285 | 0.025 |

| SSMIS apply | 0.44 | 0.150 | 0.437 | 2.907 | 0.005 |

| SSMIS harm to self-esteem | 0.07 | 0.143 | 0.074 | 0.467 | 0.642 |

| PDDQ perceived stigma | -0.80 | 1.669 | -0.050 | -0.477 | 0.635 |

| ISMIS alienation | 5.36 | 2.548 | 0.311 | 2.105 | 0.039 |

| ISMIS stereotype endorsement | 3.49 | 3.806 | 0.130 | 0.916 | 0.362 |

| ISMIS discrimination experience | 0.63 | 2.928 | 0.032 | 0.216 | 0.829 |

| ISMIS social withdrawal | 2.43 | 3.003 | 0.124 | 0.809 | 0.421 |

| BLOCK 4 R2=0.51, p<0.05 | |||||

| SSMIS awareness | 0.04 | 0.076 | 0.047 | 0.457 | 0.649 |

| SSMIS agreement | 0.23 | 0.085 | 0.305 | 2.731 | 0.008 |

| SSMIS apply | 0.35 | 0.153 | 0.346 | 2.262 | 0.027 |

| SSMIS harm to self-esteem | -0.02 | 0.141 | 0.024 | 0.149 | 0.882 |

| PDDQ perceived stigma | -1.34 | 1.654 | -0.084 | -0.808 | 0.421 |

| ISMIS alienation | 3.357 | 2.672 | 0.195 | 1.256 | 0.213 |

| ISMIS stereotype endorsement | 4.1 | 3.735 | 0.152 | 1.096 | 0.277 |

| ISMIS discrimination experience | 0.16 | 2.873 | 0.008 | 0.056 | 0.956 |

| ISMIS social withdrawal | 2.62 | 2.940 | 0.134 | 0.892 | 0.375 |

| CESD | 0.24 | 0.114 | 0.246 | 2.085 | 0.041 |

| DEPENDENT VARIABLE∷ Beck Hopelessness Scale, FOLLOW-UP BLOCK 1 N= 75; R2=0.39, p<0.001 | |||||

| INDEPENDENT VARIABLES (all baseline) | B | SE B | β | t | p |

| SSMIS awareness | -0.01 | 0.075 | -0.017 | -0.175 | 0.862 |

| SSMIS agreement | 0.10 | 0.088 | 0.134 | 1.175 | 0.244 |

| SSMIS apply | 0.38 | 0.160 | 0.407 | 2.383 | 0.020 |

| SSMIS harm to self-esteem | 0.27 | 0.139 | 0.314 | 1.911 | 0.060 |

| BLOCK 2 R2=0.42, p<0.06 | |||||

| SSMIS awareness | -0.06 | 0.077 | -0.074 | -0.731 | 0.467 |

| SSMIS agreement | 0.102 | 0.086 | 0.132 | 1.181 | 0.242 |

| SSMIS apply | 0.403 | 0.157 | 0.431 | 2.560 | 0.013 |

| SSMIS harm to self-esteem | 0.189 | 0.143 | 0.223 | 1.325 | 0.189 |

| PDDQ perceived stigma | 3.324 | 1.734 | 0.204 | 1.917 | 0.059 |

| BLOCK 3 R2=0.48, ns | |||||

| SSMIS awareness | -0.099 | 0.084 | -0.130 | -1.181 | 0.242 |

| SSMIS agreement | 0.057 | 0.094 | 0.073 | 0.601 | 0.550 |

| SSMIS apply | 0.380 | 0.156 | 0.406 | 2.439 | 0.017 |

| SSMIS harm to self-esteem | 0.061 | 0.149 | 0.072 | 0.409 | 0.684 |

| PDDQ perceived stigma | 2.346 | 1.754 | 0.144 | 1.337 | 0.186 |

| ISMIS alienation | 3.089 | 2.700 | 0.182 | 1.144 | 0.257 |

| ISMIS stereotype endorsement | 4.046 | 4.201 | 0.157 | 0.963 | 0.339 |

| ISMIS discrimination experience | 2.081 | 3.140 | 0.107 | 0.663 | 0.510 |

| ISMIS social withdrawal | 3.313 | 3.276 | 0.173 | 1.011 | 0.316 |

| BLOCK 4 R2=0.49, ns | |||||

| SSMIS awareness | 0.094 | 0.083 | 0.123 | 1.124 | 0.265 |

| SSMIS agreement | 0.098 | 0.097 | 0.128 | 1.016 | 0.313 |

| SSMIS apply | 0.316 | 0.159 | 0.337 | 1.981 | 0.052 |

| SSMIS harm to self-esteem | 0.105 | 0.150 | 0.124 | 0.702 | 0.485 |

| PDDQ perceived stigma | 1.938 | 1.753 | 0.119 | 1.105 | 0.273 |

| ISMIS alienation | 1.453 | 2.864 | 0.086 | 0.508 | 0.614 |

| ISMIS stereotype endorsement | 3.555 | 4.165 | 0.138 | 0.854 | 0.397 |

| ISMIS discrimination experience | 1.615 | 3.119 | 0.083 | 0.518 | 0.606 |

| ISMIS social withdrawal | 3.336 | 3.239 | 0.174 | 1.030 | 0.307 |

| CESD | 0.186 | 0.117 | 0.202 | 1.580 | 0.119 |

| DEPENDENT VARIABLE: Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES), BASELINE BLOCK 1 N= 75; R2=0.44, p<0.001 | |||||

| INDEPENDENT VARIABLES (all baseline) | B | SE B | β | t | p |

| SSMIS awareness | 0.000 | 0.003 | -0.007 | -0.076 | 0.940 |

| SSMIS agreement | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.039 | 0.387 | 0.700 |

| SSMIS apply | 0.012 | 0.007 | 0.257 | 1.714 | 0.090 |

| SSMIS harm to self-esteem | 0.020 | 0.006 | 0.459 | 3.187 | 0.002 |

| BLOCK 2 R2=0.47, p<0.05 | |||||

| SSMIS awareness | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.076 | 0.804 | 0.424 |

| SSMIS agreement | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.032 | 0.322 | 0.749 |

| SSMIS apply | 0.013 | 0.007 | 0.269 | 1.832 | 0.071 |

| SSMIS harm to self-esteem | 0.016 | 0.006 | 0.376 | 2.578 | 0.012 |

| PDDQ perceived stigma | 0.164 | 0.075 | 0.216 | 2.186 | 0.032 |

| BLOCK 3 R2=0.62, p<0.001 | |||||

| SSMIS awareness | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.133 | 1.491 | 0.140 |

| SSMIS agreement | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.013 | 0.139 | 0.890 |

| SSMIS apply | 0.011 | 0.006 | 0.239 | 1.867 | 0.066 |

| SSMIS harm to self-esteem | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.128 | 0.942 | 0.349 |

| PDDQ perceived stigma | 0.077 | 0.068 | 0.102 | 1.139 | 0.258 |

| ISMIS alienation | 0.365 | 0.104 | 0.441 | 3.511 | 0.001 |

| ISMIS stereotype endorsement | 0.073 | 0.155 | 0.057 | 0.471 | 0.639 |

| ISMIS discrimination experience | 0.149 | 0.119 | 0.157 | 1.248 | 0.216 |

| ISMIS social withdrawal | 0.094 | 0.122 | 0.101 | 0.768 | 0.445 |

| BLOCK 4 R2=0.65, p<0.05 | |||||

| SSMIS awareness | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.130 | 1.504 | 0.137 |

| SSMIS agreement | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.063 | 0.669 | 0.506 |

| SSMIS apply | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.150 | 1.160 | 0.250 |

| SSMIS harm to self-esteem | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.178 | 1.338 | 0.185 |

| PDDQ perceived stigma | 0.052 | 0.067 | 0.068 | 0.779 | 0.439 |

| ISMIS alienation | 0.270 | 0.108 | 0.327 | 2.504 | 0.014 |

| ISMIS stereotype endorsement | 0.102 | 0.151 | 0.079 | 0.675 | 0.502 |

| ISMIS discrimination experience | 0.127 | 0.116 | 0.133 | 1.092 | 0.279 |

| ISMIS social withdrawal | 0.085 | 0.119 | 0.091 | 0.716 | 0.476 |

| CESD | 0.011 | 0.005 | 0.242 | 2.439 | 0.017 |

| DEPENDENT VARIABLE∷ Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES), FOLLOW-UP BLOCK 1 N= 75; R2=0.39, p<0.001 | |||||

| INDEPENDENT VARIABLES (all baseline) | B | SE B | β | t | p |

| SSMIS awareness | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.068 | 0.693 | 0.491 |

| SSMIS agreement | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.032 | 0.278 | 0.782 |

| SSMIS apply | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.162 | 0.949 | 0.346 |

| SSMIS harm to self-esteem | 0.020 | 0.007 | 0.481 | 2.927 | 0.005 |

| BLOCK 2 R2=0.44, p<0.05 | |||||

| SSMIS awareness | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.060 | 0.952 |

| SSMIS agreement | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.029 | 0.268 | 0.789 |

| SSMIS apply | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.193 | 1.168 | 0.247 |

| SSMIS harm to self-esteem | 0.015 | 0.007 | 0.362 | 2.192 | 0.032 |

| PDDQ perceived stigma | 0.212 | 0.083 | 0.267 | 2.557 | 0.013 |

| BLOCK 3 R2=0.52, p<0.05 | |||||

| SSMIS awareness | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.089 | 0.852 | 0.397 |

| SSMIS agreement | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.045 | 0.387 | 0.700 |

| SSMIS apply | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.144 | 0.908 | 0.367 |

| SSMIS harm to self-esteem | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.182 | 1.087 | 0.281 |

| PDDQ perceived stigma | 0.152 | 0.081 | 0.191 | 1.866 | 0.066 |

| ISMIS alienation | 0.249 | 0.125 | 0.302 | 1.992 | 0.051 |

| ISMIS stereotype endorsement | 0.173 | 0.195 | 0.138 | 0.891 | 0.376 |

| ISMIS discrimination experience | 0.157 | 0.145 | 0.166 | 1.079 | 0.285 |

| ISMIS social withdrawal | 0.064 | 0.152 | 0.068 | 0.419 | 0.677 |

| BLOCK 4 R2=0.56, p<0.05 | |||||

| SSMIS awareness | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.080 | 0.780 | 0.438 |

| SSMIS agreement | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.025 | 0.210 | 0.834 |

| SSMIS apply | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.055 | 0.348 | 0.729 |

| SSMIS harm to self-esteem | 0.010 | 0.007 | 0.249 | 1.503 | 0.138 |

| PDDQ perceived stigma | 0.126 | 0.080 | 0.159 | 1.578 | 0.119 |

| ISMIS alienation | 0.147 | 0.130 | 0.178 | 1.126 | 0.265 |

| ISMIS stereotype endorsement | 0.143 | 0.190 | 0.114 | 0.752 | 0.455 |

| ISMIS discrimination experience | 0.128 | 0.142 | 0.135 | 0.899 | 0.372 |

| ISMIS social withdrawal | 0.065 | 0.148 | 0.070 | 0.440 | 0.661 |

| CESD | 0.012 | 0.005 | 0.260 | 2.168 | 0.034 |

N.B.. SSMIS Self Stigma of Mental Illness Scale; BHS: Beck Hopelessness Scale; ISMISS Internalized Sigma of Mental Illness Scale; RSES: Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale,

The first set of blocks in Table 1 examined stigma at baseline and hope at baseline. Block 1 showed BHS-baseline to be separately associated with SSMIS-2 (Agree) and SSMIS-3 (Apply). These associations remained significant in subsequent blocks with the PDDQ, ISMIS, and CES-D. ISMIS alienation also yielded a significant relationship in the third block which disappeared in the last block where the CES-D score was added and found to be significant. R2 for block four was high representing 51% of the variance. Relationship of self-stigma and depression variables at baseline with follow-up hope was examined in the next set of blocks. Here, a slightly different pattern was found between SSMIS scores and hope at follow-up. Namely, hope was found to be significantly and independently related to SSMIS-3 apply; a nonsignificant trend was found in the association with SSMIS-4 harm. Relationship between hope and the apply scale score in the remaining blocks was significant but not so for harm. Part of the loss in significance may be the addition of perceived stigma in block 2. Only SSMIS-apply was significant with follow-up hope in the remaining blocks. All four blocks accounted for 49% of the variance in hope at follow-up.

The next two sets of analyses examined self-stigma with self-esteem at baseline and follow-up. The harm scale was found to be significantly associated with baseline self-esteem while a nonsignificant trend P>0.10) described the relationship between apply and self-esteem. Perceived stigma was significantly associated with self-esteem in Block 2 as was SSMIS harm; the relationship between apply and self-esteem remained a nonsignificant trend. Significant relationships among SSMIS scores and self-esteem disappeared in the third block, replaced by a significant association with the alienation scale of the ISMIS. CESD depression was also significantly associated with alienation in Block 4. R2 was 0.65. The final set of regression analyses examined self-esteem at follow-up with the stigma scales. Only SSMIS harm was significantly associated with the RSES total score in the first block. Both harm and perceived stigma were associated with self-esteem in Block 2. All the SSMIS values were uncorrelated with self-esteem in Blocks 3 and 4. Only CESD was found significant with RSES follow-up in Block 4. Total R2 was 0.56.

4. Discussion

A progressive model of self-stigma was examined in order to address limitations of other models that largely viewed the phenomenon as static and unipolar. Some of the analyses from the study supported the hypotheses while others led us to reconsider some assumptions. One way the progressive model was examined was to test for trickle down. Data partially confirmed this; awareness of stereotypes was significantly higher than agreement which in turn was higher than values for self-apply and harm. No significant difference was found between SSMIS apply and harm, which seems to be a trend through many of the subsequent analyses. Correlations between apply and harm were very high at baseline and follow-up accounting for more than 62 to 65% of the variance respectively. In further support of the overall progressive model, correlations between immediately proximal associations were higher than Pearson r's representing correlations with every other stage. The exception to this rule was the relationship between awareness and the three other stages, a bit of a surprise given the robust difference between aware and agree.

The progressive model was proposed in part to suggest relatively unipolar descriptions of self-stigma that focus on perception or agreement with stereotypes are limiting, that using multiple scales of the SSMIS accounts for more variance in outcome measures. Two such outcomes important for recovery were selected here: self-esteem and its emotional correlate, hope. Agree and apply were shown to be separately and significantly associated with the baseline BHS scale score. However, SSMIS apply and harm to self-esteem were found to be similarly associated at follow-up in Block 1 of the multiple regression. Relationships of SSMIS scales representing apply and harm to self-esteem at follow-up were more consistent with hypotheses. Subsequent, addition of selected blocks of variables for the BHS outcome at baseline and follow-up showed the independence of SSMIS scores from related constructs. For baseline analyses, SSMIS agreement and application remained significant with no construct adding significant variance to the regression model. At follow-up, the self-application score remained significant after adding the different blocks. An additional finding is worth noting here; namely, that the relationship between SSMIS scores and hope remained significant even after partialling out depression.

In summary, what has been shown vis-à-vis the progressive model? Splitting stages into two sets, between agree and apply seemed meaningful and is consistent with other findings (Corrigan et al., 2006; Rüsch et al, 2006). These findings paralleled work on the PDDQ (Link, 1987) and ISMIS (Ritsher & Phelan, 2004). Moreover and as expected, it was the latter stages – self-apply and harm – that yielded significantly greater association with negative impacts on hopelessness and self-esteem. Hence, assessing perception of stereotypes is not sufficient to understand its impact. In the Introduction, it was noted that growing up in any culture leads people with mental illness to be aware of the stereotypes about their condition. It is only when they apply those hurtful beliefs to themselves that the truly negative impact of self-sigma is observed.

There are limitations to the study; the progressive model was not supported in toto. This limitation was addressed by reorganizing into two sets of stages: the awareness-agreement primary stage followed up by application-harm. A subsequent study needs to replicate this framework. One of the benefits of the progressive model of self-stigma is its direct implications for behavior. This has been presented as the “why try” effect related to self-stigma (Corrigan et al., 2009). “Why try to get a job? Someone like me is not deserving.” Hence, the SSMIS will have greater value if shown to be associated with behavioral proxies of “why try.” A measure of why try should be included in subsequent investigations into the progressive model. There are additional concerns with the study. Future studies need to also examine heterogeneity, how self-stigma varies with demographics such as gender and ethnicity, as well as indicators of psychopathology including diagnosis, symptoms and course.

Awareness is a complex variable. Research shows many people with serious mental illness have muted insight into their disorders, seemingly unaware of symptoms and their impact (Amador & David, 2004). Can this person be impacted by stigma if they are unaware they fall into a stigmatized group? Other people who may recognize their illness might be unaware of the stigma that accompanies it (Corrigan & Watson, 2002). They seem to understand their symptoms and disabilities but are unaware of stereotypes that correspond with them. Awareness in its complexity offer theoretically important foci for future research.

Ultimately, the worth of any stigma measure is its utility in terms of stigma change. Cognitive therapies are being examined as useful ways to challenge stereotypes that lead to harm (Holzinger et al., 2008). Research on the progressive model suggests an additional direction, one that is preventive in scope. Awareness of stereotypes is unavoidable. But agreeing with the stereotype, believing they are factual in describing others with mental illness and one's self, is open to challenge and counters. Alternatively, mutual support might be an effective way to deal with self-stigma. Research has shown people with serious mental illness involved in self-help and other mutual support programs report less self-stigma and better quality of life (Corrigan et al., in review). Both these approaches offer promise in helping people with mental illness replace self-stigma with hope and self-esteem.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amador XF, Flaum M, Andreasen NC, Strauss DH, Yale SA, Clark SC, Gorman JM. Awareness of illness in schizophrenia and schizoaffective and mood disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;51:826–836. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950100074007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L. The measurement of pessimism: the Hopelessness Scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1974;42:861–865. doi: 10.1037/h0037562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohan E, Elgie R, Sartorius N, Thornicroft G. Self-stigma, empowerment and perceived discrimination among people with schizophrenia in 14 European countries: the GAMIAN-Europe study. Schizophrenia Research. 2010a;122:232–238. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.02.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohan E, Gauci D, Sartorius N, Thornicroft G GAMIAN-Europe Study Group. Self-stigma, empowerment and perceived discrimination among people with bipolar disorder or depression in 13 European countries: the GAMIAN-Europe study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010b;129:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher MS, Jacob KL, Neuhaus EC, Neary TJ, Fiola LA. Cognitive and behavioral changes related to symptom improvement among patients with a mood disorder receiving intensive cognitive-behavioral therapy. Psychiatric Practice. 2009;15:95–102. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000348362.11548.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, editor. On the stigma of mental illness: implications for research and social change. American Psychological Association Press; Washington DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Larson JE, Rüsch N. Self-stigma and the “why try” effect: impact on life goals and evidence-based practices. World Psychiatry. 2009;8:75–81. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00218.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Sokol KA, Rüsch N. The impact of self-stigma and mutual help programs on the quality of life of people with serious mental illnesses. doi: 10.1007/s10597-011-9445-2. Manuscript submitted to Community Mental Health Journal. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC. The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9:35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Barr L. Understanding the self-stigma of mental illness. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2006;25:875–884. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B. The self-protective properties of stigma: Evolution of a modern classic. Psychological Inquiry. 2003;14:232–237. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Major B, Crocker J. Stigma: introduction and overview. In: Heatherton TF, Kleck RM, Hebl MR, Hull JD, editors. The Social Psychology of Stigma. The Guilford Press; New York: 2000. pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Holzinger A, Dietrich S, Heitmann S, Angermeyer MC. Evaluation zielgruppenorientierter interventionen zur reduzierung des stigmas psychischer krankheit. Eine systematische übersicht. [Evaluation of target-group oriented interventions aimed at reducing the stigma surrounding mental illness. A systematic review]. Psychiatrische Praxis. 2008;35:376–386. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1067396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG. Understanding labeling effects in the areas of mental disorders: an assessment of the effects of expectations of rejections. American Sociological Review. 1987;52:96–112. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Struening EL, Rahav M, Phelan JC, Nuttbrock L. On stigma and its consequences: evidence from a longitudinal study of men with dual diagnoses of mental illness and substance abuse. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38:177–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston JD, Rossiter KR, Verdun-Jones SN, McMillan D, Gilbody SM, Beresford E, Neilly L. ‘Forensic’ labelling: an empirical assessment of its effects on self-stigma for people with severe mental illness. Can we predict suicide and non-fatal self-harm with the Beck Hopelessness Scale? a meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine. 2011;37:769–778. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro LC, Silva VA, Louzã MR. Insight, cognitive dysfunction and symptomatology in schizophrenia. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2008;258:402–405. doi: 10.1007/s00406-008-0809-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlick DA, Rosenheck RA, Clarkin JF, Sirey JA, Salahi J, Struening EL, Link BG. Adverse effects of perceived stigma on social adaptation of persons diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:1627–1632. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ritsher JB, Otilingam PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: Psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Research. 2003;121:31–49. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritsher JB, Phelan JC. Internalized stigma predicts erosion of morale among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatry Research. 2004;129:257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers ES, Chamberlin J, Ellison ML, Crean T. A consumer-constructed scale to measure empowerment among users of mental health services. Psychiatric Services. 1997;48:1042–1047. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.8.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Corrigan PW, Wassel A, Michaels P, Olschewski M, Wilkniss S, Batia K. A stress-coping model of mental illness stigma: I. Predictors of cognitive stress appraisal. Schizophrenia Research. 2009;110:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Hölzer A, Hermann C, Schramm E, Jacob G, Bohus M, Lieb K, Corrigan PW. Self-stigma in women with borderline personality disorder and women with social phobia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194:766–773. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000239898.48701.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for the DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steed L. Further validity and reliability evidence for Beck Hopelessness Scale scores in a nonclinical sample. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2001;61:303–316. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanopoulou E, Lafuente AR, Saez Fonseca JA, Huxley A. Insight, global functioning and psychopathology amongst in-patient clients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2009;80:3155–3165. doi: 10.1007/s11126-009-9103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson AC, Corrigan PW, Larson JE, Sells M. Self-stigma in people with mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007;33:1312–1318. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS, Robertson GJ. Wide Range Achievement Test--Fourth Edition. Psychological Assessment Resources; Lutz, FL: 2006. [Google Scholar]