Abstract

First-episode psychosis typically emerges during late adolescence or young adulthood, interrupting achievement of crucial educational, occupational, and social milestones. Recoveryoriented approaches to treatment may be particularly applicable to this critical phase of the illness, but more research is needed on the life and treatment goals of individuals at this stage. Open-ended questions were used to elicit life and treatment goals from a sample of 100 people hospitalized for first-episode psychosis in an urban, public-sector setting in the southeastern United States. Employment, education, relationships, housing, health, transportation were the most frequently stated life goals. When asked about treatment goals, participants' responses included wanting medication management, reducing troubling symptoms, uncertainty, a desire to simply be well, engaging in counseling, and attending to their physical health. In response to queries about specific services, most indicated a desire for both vocational and educational services, as well as assistance with symptom and drug abuse. These findings are interpreted and discussed in light of emerging or recently advanced treatment paradigms—recovery and empowerment, shared decision-making, community and social reintegration, and phase-specific psychosocial treatment. Integration of these paradigms would likely promote recovery-oriented tailoring of early psychosocial interventions, such as supported employment and supported education, for first-episode psychosis.

Keywords: First-episode psychosis, Recovery, Schizophrenia, Supported Education, Supported Employment

Introduction

Nonaffective psychotic disorders often emerge during late adolescence or early adulthood, a time in life when individuals normally achieve important educational, vocational, and relationship milestones. People with emerging schizophrenia are often derailed at this stage, developing significant educational, occupational, and interpersonal deficits (Hafner et al., 1995). The early stages of psychosis are often considered to be a “critical period” (Birchwood, 1999), as long-term follow-up studies show that two-year outcomes strongly predict longer-term illness outcomes (Harrison, 2001). Evidence suggests that treatment is more effective when implemented earlier, though early intervention is a relatively new concept in the mental health field (Drake, 2000).

The early intervention paradigm involves timely, phase-specific initiation of both pharmacologic and evidence-based psychosocial treatments. Yet, these ideal approaches are often complicated by little availability of specialized services and problems with patient insight and adherence. Impaired insight, which is not a willful denial but rather a part of the illness itself, commonly results in noncompliance with medications and psychosocial interventions (Lysaker and Bell, 1994; Burton, 2005; Tasang et al., 2009) and differences in treatment goals between patients and their providers only compound this situation (Chue, 2006; Diamond, 2006). To bridge this gap, the recovery model, a more personalized and patient-centered approach to caring for persons who have mental illnesses, has emerged (Jacobson and Greenley, 2001).

The traditional medical concept of “recovery” (i.e., a person is cured from or no longer contends with an illness), has been replaced by some within the medical field with a new conceptualization, which is believed to better account for the oftentimes persistent nature of serious mental illnesses. Within this framework, recovery is thought to be a process rather than an outcome, and is focused on the individual and his or her journey toward attainment of personal recovery and life goals, rather than the absence of symptoms (Buckley et al., 2007). Fundamental elements of the recovery model include consumers assuming more responsibility in developing plans for achieving their goals, and working collaboratively with mental health providers and their support systems (Jacobson and Greenley, 2001).

To embrace the recovery model, clinicians, researchers, and program planners must understand consumers’ own goals. At present, there is a paucity of research investigating what people with first-episode psychosis want from treatment. The objective of this investigation was to summarize the life and treatment goals of a sample of individuals hospitalized for treatment of first-episode nonaffective psychosis, along with their perception of how mental health professionals could assist them. Understanding their goals may reveal essential implications for recovery-oriented tailoring of early psychosocial interventions.

Methods

Setting and Sample

Participants were recruited from the psychiatric units of a large, urban, university-affiliated, public-sector hospital (n=82) and a suburban county psychiatric crisis center (n=18), as part of a larger, ongoing study in the southeastern United States. These treatment centers predominantly serve urban African Americans. To be eligible, individuals must be hospitalized for a first episode of a nonaffective psychotic disorder and provide written informed consent. Those with known mental retardation, a Mini-Mental State Examination (Cockrell and Folstein, 1988) score of <23, a significant medical condition compromising their ability to participate, prior antipsychotic treatment of >3 months duration, previous hospitalization for psychosis occurring >3 months prior to index hospitalization, or inability to provide informed consent were excluded.

Procedures

The procedures were approved by all relevant ethical review boards. The assessment typically took place after the initial stabilization of symptoms and treatment planning (hospital day mean and median of 5.1 and 5.0). The index hospitalization was the first professional help-seeking contact for 44 (44.0%) of participants. Of those who had had previous contacts, the mean and median number of previous healthcare contacts (typically an outpatient appointment with a psychiatrist or an emergency room visit) was 4.2 and 2.

A number of sociodemographic variables were assessed. Employment status was determined by asking if the participant had a job during the past month. Information about household income was obtained from the individual and, when available, family members. Presence of Axis IV psychosocial problems (including problems in the following areas: primary support, the social environment, education, occupation, finances, housing, access to health care, interactions with the legal system, and other areas) was determined after the full research assessment (typically lasting about 6–7 hours, and including questions in these areas) was complete. Nonaffective psychotic and substance use disorder diagnoses were derived with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (First et al., 1998).

For this report, qualitative descriptions of participants’ life and treatment goals were gathered through a brief, structured interview that was developed based on existing literature on the recovery model. The interview included five open-ended questions pertaining to life and treatment goals, three of which are examined herein:

How could mental health professionals be helpful to you in the upcoming few years?

What are your top three goals for the upcoming few years?

What would your top three treatment goals be, working with mental health professionals?

Participants were given adequate time to generate as many responses as they would like. In addition, four closed-ended questions were used to assess participants’ desire for certain services, including those related to “finding a job,” “going back to school or getting more education,” “staying off drugs,” and “getting rid of symptoms.” Questions were formatted as follows, If services were available, would you like assistance from mental health professionals with [finding a job]?

Participants’ responses were written and entered into a dataset. Salient themes were elicited through an inductive approach, such that similar responses were grouped together and emergent categories were first observed, then refined (Pope et al., 2000). The development and finalization of themes within each category was conducted by two of the authors and then reviewed by another.

Results

The participants (n=100) were, on average, 24.3 ± 5.1 years of age, with a mean educational attainment of 11.7 ± 2.9 years. As shown in Table 1, this sample is predominately single, male, African American, and unemployed. Other demographic characteristics, as well as SCID-derived diagnoses for psychotic, cannabis use, and alcohol use disorders are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Individuals with First-Episode Psychosis (n=100).

| Age at hospitalization, years | 24.3 ± 5.1 |

| Gender, male | 74 (74.0%) |

| Race, Black or African American | 89 (89.0%) |

| Relationship status, never married | 87 (87.0%) |

| Has children | 36 (36.0%) |

| Years of education | 11.7 ± 2.9 |

| Currently or very recently employed | 33 (33.0%) |

| Income below the federal poverty line (n=79) | 29 (39.2%) |

| Number of Axis IV psychosocial problems | 3.9 ± 2.2 |

| SCID psychotic disorder diagnosis | |

| Schizophrenia | 56 (56.0%) |

| Psychotic disorder not otherwise specified | 17 (17.0%) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 14 (14.0%) |

| Schizophreniform disorder | 8 (8.0%) |

| Delusional disorder | 3 (3.0%) |

| Brief psychotic disorder | 2 (2.0%) |

| SCID alcohol use disorder (n=93) | |

| No disorder | 62 (66.7%) |

| Abuse | 12 (12.9%) |

| Dependence | 19 (20.4%) |

| SCID cannabis use disorder (n=92) | |

| No disorder | 37 (40.2%) |

| Abuse | 14 (15.2%) |

| Dependence | 41 (44.6%) |

When asked to list their top three life goals for the upcoming years, the top priorities, as shown in Table 2, included goals in the following domains: employment, education, relationships, housing, health, transportation, and others. On average, 2.8 ± 0.87 distinct life goals were elicited and only 3 individuals did not report any life goals for the next few years, while 85 reported 3 or more. Over half of participants reported wanting a job. Some had specific employment goals (e.g., establishing a barbershop) while others placed value on “finding a stable job.” Education was a priority for more than a third, many of whom wanted to go to college or complete high school (secondary education). Over a third of participants stated that they wanted to build or strengthen their relationships; some talking about family members (e.g. “spending time with my son”) and others hoping to maintain or find a romantic partnership or friendships. Thirty participants mentioned a health-related goal, such as ensuring their general health/wellbeing (15.0%), recovering from their illness or symptoms (10.0%), and improving their physical health (5.0%). A quarter of the sample wanted to obtain independent housing, or had other goals, as shown in Table 1, including transportation, practicing art, and spirituality. The vast majority of participants (95.0%) readily listed more than one goal for the upcoming few years.

Table 2.

Life Goals of Individuals with First-Episode Psychosis for the Upcoming Years (n=100).

| Goal | Percentage of participants who spontaneously listed the goal |

Important themes or representative quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Employment | 53.0% | Finding a job. Owning a business. Practicing a trade. |

| Education | 38.0% | Obtaining a high school degree. Going to or finishing college. Obtaining vocational training. |

| Relationships | 35.0% | Focusing on family. Raising a child. Developing new relationships. |

| Housing | 25.0% | Having one’s own place to live. |

| Health | 15.0% | “I want to get my life on track”. “I want to have fun again”. |

| Transportation | 15.0% | “I want to have my own car”. |

| Art and music | 12.0% | “I want to get my own record label”. |

| Financial stability | 11.0% | Obtaining wealth. Money management. |

| Recovering from current mental illness | 10.0% | “I want to appreciate what I’ve been through and realize that things will get better”. |

| Spirituality | 8.0% | Developing a relationship with God. Joining a church. |

| Other | 8.0% | Un-replicated or vague responses. |

| Improving physical health or athleticism | 5.0% | “I want to get my body the way I want it to be” |

As shown in Table 3, when asked to list their top three treatment goals, common responses included medication management, reduction of troubling symptoms, uncertainty (“I don’t know”), a desire to simply be well, engaging in counseling, attending to physical health, cultivating a positive attitude, and others. On average, participants listed 1.8 ± 1.2 distinct treatment goals, and a quarter of participants either did not know what treatment goals they could have or did not want to participate in treatment at all. Participants most often spoke of taking medications as a priority, though a few individuals expressed a desire to discontinue their medications instead. Approximately one quarter of participants reported a desire to address specific symptoms, such as auditory hallucinations (6%), disorganization or attention deficits (6%), anger management (6%), and depression (5%). A single individual expressed a desire pertaining to reality orientation, stating that he wanted “to get the difference between what’s real and what’s not.” A sizeable minority of participants (17%) simply said that they did not know what treatment they wanted, and others (15%) gave non-specific responses such as “to get better.” Other treatment goals are shown in Table 3, as well as subthemes (where applicable) and representative quotes.

Table 3.

Treatment Goals of Individuals with First-Episode Psychosis (n=100).

| Treatment goal | Percentage of participants who spontaneously listed the goal |

Important themes or representative quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Medication management | 26.0% | Continue taking medications. Finding the right medication. |

| Reduction of troubling symptoms | 24.0% | Reduction of auditory hallucinations. Improvement in attention and ‘mental organization’. Anger management and impulse control. Alleviation from depression. |

| I don’t know | 17.0% | “I’m don’t know”. “The doctor should answer that. Not me”. |

| A desire to simply be well | 15.0% | “I want to get my mind working properly”. “I want to be better”. |

| Engaging in counseling | 14.0% | “I want to talk about it”. |

| Attending to physical health | 12.0% | Accessing primary medical care Improving general health |

| Cultivating a positive attitude | 12.0% | “I want to work on having a more positive attitude”. |

| Others | 12.0% | Un-replicated or vague responses. |

| No treatment goals needed or wanted | 8.0% | “I don’t have a mental problem”. |

| Learning about their diagnosis or condition | 7.0% | “Teach me exactly what is going on”. |

| Staying off of drugs | 7.0% | Abstinence from alcohol or drugs |

| Discontinuation of hospitalization or of medications | 7.0% | “Get me out of here”. “I want to get off medications”. |

| Joining a treatment program | 7.0% | Joining or staying in a program |

| Life goals | 6.0% | Housing, education, employment, parenting |

When asked in an open-ended format how mental health professionals could best help them, participants most often expressed an interest in having someone to talk to, obtaining medications, or not wanting help. Just over one quarter of individuals stated that they would find counseling helpful. Some said that this could help them with coping skills, specific symptoms, or questions of self-identity. The next most frequent response pertained to medications, with participants stating that mental health professionals could provide these and could assist them with continued adherence. Some participants (17%) stated that they did not want help from mental professionals at all. Others mentioned symptom relief, assistance with other needs, and education about diagnosis. Additional themes and representative quotes are show in Table 4.

Table 4.

How Mental Health Professionals Can Help, as Described by Individuals with First-Episode Psychosis (n=100).

| Treatment goal | Percentage of participants who spontaneously listed the goal |

Important themes or representative quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Having someone to talk to | 26.0% | “Be like a guidance, helping me figure out my questions I have about what I'm going through”. “Help me cope”. “Help me get to know myself”. |

| Obtaining medications | 18.0% | They can prescribe medications and help with adherence |

| I don’t know | 17.0% | “I’m not sure, just whatever you think you can do”. |

| Symptom relief | 12.0% | Managing emotions Managing auditory hallucinations Feeling better, overall. |

| Other | 12.0% | Un-replicated or vague responses. |

| Logistical or life needs | 8.0% | “Help me continue to have a regular life”. |

| Not wanting help | 8.0% | “They can’t help me”. |

| Clarifying the diagnosis | 6.0% | “Help diagnose me. So I can get proper help”. |

| Education about diagnosis | 5.0% | “Teach me about my illness, weight gain, and medicines that I 'm taking”. |

| Coping | 5.0% | “Teach me how to cope”. |

When asked about specific services (“finding a job,” “going back to school or getting more education,” “staying off drugs,” and “getting rid of symptoms.”), a majority of participants endorsed wanting assistance in these areas (Table 5). Whereas 53.0% spontaneously indicated that obtaining employment was one of their top three life goals, 80.0% responded “yes” when asked if they would like assistance from mental health professionals in finding a job. Similarly, 38.0% listed education pursuits as one of their top three goals, but 75.0% indicated that they would like assistance going back to school when asked directly. One quarter mentioned their mental health among top life goals, while 73.0% replied that they would like help getting rid of symptoms in response to this specific question. Approximately half endorsed an interest in help staying off of drugs, though none had spontaneously listed this as a top life goal. Among those individuals (n=25) who did not spontaneously list any treatment goals, 17 (68.0%) answered that they would like assistance from mental health professionals with finding a job and 16 (64.0%) endorsed wanting help with getting more education. Fewer of those individuals wanted help with symptoms (12, 48.0%), and less than a third (8, 32.0%), wanted help staying off of drugs.

Table 5.

Employment, Education, Drug Treatment, and Symptom Reduction: Alignment with Life Goals of Individuals with First-Episode Psychosis (n=100).

| Goal | Listed spontaneously as a life goal in open-ended format |

Related services endorsed as desirable in closed-ended format |

|---|---|---|

| Finding a job | 53.0% | 80.0% |

| Going back to school or Getting more education | 38.0% | 75.0% |

| Staying off drugs | 0.0% | 51.0% |

| Getting rid of symptoms | 25.0% | 73.0% |

Discussion

Responses from open-ended questions about life goals in this sample of individuals with first-episode psychosis were dominated by: employment, education, relationships, housing, and health. The most frequently cited treatment goals were staying on medications and addressing specific symptoms. Perceived opportunities for assistance from mental health professionals revolved around having someone to talk to, obtaining medications, and symptom relief. However, participants appeared to be remarkably open to other types of assistance when asked directly. The pattern of responses seems to indicate that these individuals had broad, developmentally appropriate, non-psychotic life goals (e.g., employment, education). The results suggest that they had fewer and narrower treatment goals (if any), and that they viewed mental health professionals as only being able to help with narrow treatment goals (e.g., addressing specific symptoms, obtaining medications). However, when mental health professionals offered other services (e.g., assistance with employment and education), they largely endorsed wanting such help, in addition to more traditional services (e.g., medication management for symptom reduction).

Individuals in the present sample were largely in the age of emerging adulthood, when young adults typically participate in higher education; transition out of their parents’ households; explore and sometimes establish enduring romantic relationships; and focus on developing selfsufficiency, financial independence, and development of character (Arnett, 2010). These participants’ life goals were thus entirely in keeping with others in their age group. While they were not asked to rank the relative importance of their life versus treatment goals, there were several indications of an enthusiasm gap favoring the former. For instance, they generally listed a greater number of life goals than treatment goals, and often with a greater amount of detail. Nonetheless, these and other individuals with first-episode psychosis fall behind their age cohorts during this critical period far too often. High rates of unemployment are common at the first episode of psychosis and worsen over time (Marwaha & Johnson, 2004). Similarly, educational discontinuation is a common and serious consequence of serious mental illnesses (Haynes, 2002) and first-episode psychosis (Goulding et al., 2009). Because of poor functional outcomes, schizophrenia is the fifth leading cause of disability worldwide (World Health Organization, 2008).

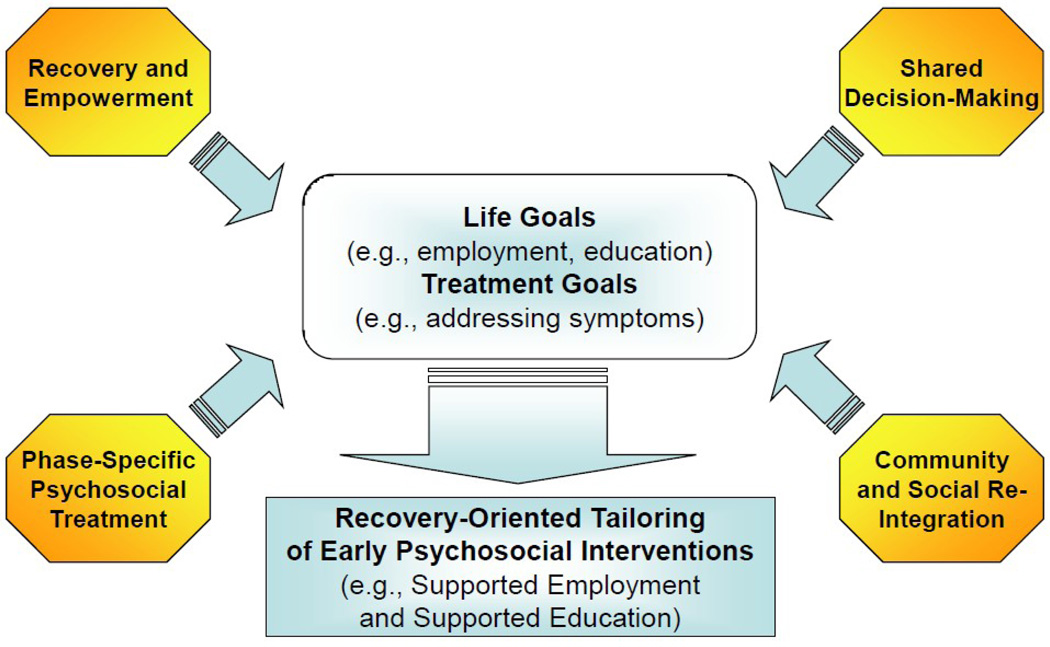

There is a growing consensus that mental health services for schizophrenia should not only target positive symptoms but also assist individuals to reengage in their community. In particular, the following four emerging or recently advanced paradigms (shown in Figure 1) can be applied towards this goal and may be particularly well-suited to first-episode psychosis: (1) recovery and empowerment, (2) shared decision-making, (3) community and social reintegration, and (4) a phase-specific approach to the treatment of psychotic disorders. Recovery is a process rather than an outcome, focused on the individual and his/her journey toward attaining goals rather than the absence of symptoms (Buckley et al., 2007). Empowerment indicates that individuals with mental illnesses assume responsibility and strive for autonomy and independence. Most definitions of empowerment include participation in society through employment, education, and other resources (Castelein et al., 2008), which is clearly in line with the life goals of the individuals in this sample. A key to unlocking the strength of empowerment and collaboration in therapeutic relationships is found in shared or participatory decision-making (Epstein et al., 2004; Kuehn, 2009), defined as “collaborative partnerships with patients (and families) in which clinical decisions are made using the best available evidence, consistent with patients’ values, goals, and capabilities” (Epstein et al., 2004). Reintegration is the process of developing and exercising interpersonal relationships and social connectedness; a stage that occurs after stabilization when psychosocial strengths have been rebuilt (Ehmann and Hanson, 2004; Ware et al., 2007; Ware et al., 2008). Early psychosis researchers emphasize that accumulated disability is often present by the time individuals with first-episode psychosis initiate treatment. The notion of “phase-specific treatment” suggests that treatment options should be tailored to the needs of young adults and their families during a critical developmental period in both their lives and their emerging illness. Supported employment and supported education are two such options, and have been implemented successfully for individuals with recent-onset schizophrenia in a few small but encouraging studies (Rinaldi et al., 2004; Killackey et al., 2006; Major et al., 2009).

Figure 1.

The Integration of Four Emerging or Recently Advanced Treatment Paradigms in Promoting the Recovery-Oriented Tailoring of Early Psychosocial Interventions in First-Episode Psychosis.

While these treatment approaches are of obvious clinical utility, they are generally only available in a few countries that offer a full array of psychosocial treatments to early-course patients and in specialized programs. In the United States, supported employment is offered in some community settings, yet less than 25% of clients with severe mental illnesses receive vocational assistance (Bond et al., 2001). Similarly, recent research suggests that psychiatrists view shared decision-making as particularly suitable for psychosocial interventions, yet only half reported applying such practices (Hamann et al., 2009). By contrast, individuals in this report appear to be slightly more open to treatment approaches like supported employment and supported education than to traditional services. This is particularly appealing in light of the high rate of treatment drop-out seen in first-episode psychosis and other psychiatric conditions (Svedberg et al., 2001; Lecomte et al., 2008). For those who do not have symptom-related treatment goals or want to discontinue treatment, vocation- and education-oriented services may be an avenue for early engagement. Further, a prior study found that more than half of a sample of individuals with schizophrenia chose practical advice as the most useful component of their psychotherapy (Coursey et al., 1995).

This descriptive study focused on the life and treatment goals of individuals who have been hospitalized for first-episode psychosis. However, a number of methodological limitations inherent to this approach must be recognized. First, this report relied on simple description of responses to open- and closed-ended questioning. Statistical analyses were not applied to the data, nor were specific hypotheses tested. However, the objective was to describe and interpret/synthesize rather than test hypotheses. Second, participants were not asked to rank the importance of their life and treatment goals, and inferences about the ones that were most salient to these individuals were made instead from observations about the number of responses and detail included across the sample. A more in-depth inquiry with specific questions about the goals that these individuals wish to obtain first and what services they consider relevant to their goal attainment would be of great utility. Finally, the study focused on a unique population from a specific geographic location, and from a sample that was quite homogenous. This undoubtedly influences the goals elicited, and they may not be generalizable to broader or dissimilar samples of individuals with first-episode psychosis. However, the intent was to examine goals in this especially vulnerable, under-studied, and relatively homogeneous sample in order to provide an example of how clinicians, researchers, and program planners should elicit goals from their patients instead of only relying on universally applicable treatment guidelines that may be more suitable for the pharmacologic aspect of treatment. More diverse samples may produce a broader array of life and treatment goals.

Opportunities clearly exist for recovery-oriented tailoring of early psychosocial interventions based on individuals’ own recovery goals. Programmatic and policy development is necessary to better align treatment services with what numerous experts have theorized in recent years (e.g., recovery/empowerment, shared decision-making, community and social reintegration, and phase-specific treatment) and with what our patients clearly request.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grant R01 MH081011 to the last author.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barrowclough C, Haddock G, Tarrier N, Lewis SW, Moring J, O'Brien R, Schofield N, McGovern J. Randomized controlled trial of motivational interviewing, cognitive behavior therapy, and family intervention for patients with comorbid schizophrenia and substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1706–1713. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker DB, Drake RE. A Working Life for People with Severe Mental Illness. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Birchwood M. The Recognition and Management of Early Psychosis: A Preventive Approach. Cambridge University Press; 1999. Early Intervention in Psychosis: The Critical Period; pp. 226–265. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman J. Work, employment and psychiatric disability. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2003;9:327–334. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, et al. Implementing Supported Employment as an Evidence-Based Practice. Psychiatric Services. 2000;52:313–322. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.3.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Drake RE, Becker DR. An update on randomized controlled trials of evidence-based supported employment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2008;31:280–290. doi: 10.2975/31.4.2008.280.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley PF, Fenley G, Mabe A, Peeples S. Recovery and schizophrenia. Clinical Schizophrenia and Related Psychoses. 2007;1:96–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Burton S. Strategies for improving adherence to second-generation antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia by increasing ease of use. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2005;11:369–378. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200511000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush PW, Drake RE, Xie H, McHugo GJ, Haslett WR. The long-term impact of employment on mental health service use and costs for persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:1024–1031. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.8.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelein S, van der Gaag M, Bruggeman R, van Busschbach JT, Wiersma D. Measuring empowerment among people with psychotic disorders: A comparison of three instruments. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59:1338–1342. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.11.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chue P. The relationship between patient satisfaction and treatment outcomes in schizophrenia. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2006;20:38–56. doi: 10.1177/1359786806071246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockrell JR, Folstein MF. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1988;24:689–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins ME, Bybee D, Mowbray CT. Effectiveness of supported education for individuals with psychiatric disabilities: results from an experimental study. Community Mental Health Journal. 1998;334:595–613. doi: 10.1023/a:1018763018186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JA, Solomon ML. The community scholar program: an outcome study of supported education for students with severe mental illness. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1993;17:83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Coursey RD, Keller AB, Farrell EW. Individual psychotherapy and persons with serious mental illness: The clients’ perspective. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1995;21:283–300. doi: 10.1093/schbul/21.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond RJ. Recovery from a Psychiatrist’s Viewpoint. Postgraduate Medicine Special Report. 2006:54–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Deegan PE. Shared decision making is an ethical imperative. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:1007. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.8.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RJ, Haley CJ, Akhtar S, Lewis SW. Causes and consequences of duration of untreated psychosis in schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;177:511–515. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.6.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehmann T, Hanson L. Social and psychological interventions. In: Ehmann T, MacEwan GW, Honer WG, editors. Best Care in Early Psychosis Intervention. Oxon, UK: Global Perspectives, Taylor & Francis; 2004. pp. 75–76. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein RM, Alper BS, Quill TE. Communicating evidence for participatory decision making. JAMA. 2004;291:2359–2366. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.19.2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Diagnoses Axis I Diagnoses. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Goulding SM, Chien VH, Compton MT. Prevalence and correlates of school drop-out prior to initial treatment of nonaffective psychosis: Further evidence suggesting a need for supported education. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;116:228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner H, Nowotny BL, an der Heiden W, Maurer K. When and how does schizophrenia produce social deficits? European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 1995;246:17–28. doi: 10.1007/BF02191811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann J, Mendel R, Cohen R, Heres S, Ziegler M, Buhner M, Kissling W. Psychiatrists’ use of shared decision making in the treatment of schizophrenia: Patient characteristics and decision topics. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:1107–1112. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.8.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison G, Hopper K, Craig T, Laska E, Siegel C, Wanderling J, Dube KC, Ganev K, Giel R, an der Heiden W, Holmberg SK, Janca A, Lee PW, León CA, Malhotra S, Marsella AJ, Nakane Y, Sartorius N, Shen Y, Skoda C, Thara R, Tsirkin SJ, Varma VK, Walsh D, Wiersma D. Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;178:506–517. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.6.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes NM. Addressing students’ social and emotional needs: the role of mental health teams in schools. J. Health. Soc. Policy. 2002;16:109–123. doi: 10.1300/j045v16n01_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman FL, Mastrianni X. The role of supported education in the inpatient treatment of young adults: a two-site comparison. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1993;17:109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N, Greenley D. What is recovery? A conceptual model and explication. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:482–48552. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.4.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killackey E, Jackson HJ, Gleeson J, Hickie IB, McGorry PD. Exciting career opportunity beckons! Early intervention and vocational rehabilitation in first-episode psychosis: Employing cautious optimism. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;40:951–962. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn BM. States Explore Shared Decision Making. JAMA. 2009;301:2539–2541. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecomte, et al. Predictors and profiles of treatment non-adherence and engagement in services problems in early psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. 2008 July;Volume 102(Issues 1–3):295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker P, Bell M. Insight and cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Performance on repeated administrations of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1994;182:656–660. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199411000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major BS, Hinton MH, Flint A, Chalmers-Brown A, McLoughlin K, Johnson S. Evidence of the effectiveness of a specialist vocational intervention following first episode psychosis: a naturalistic prospective cohort study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2009;45:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marwaha S, Johnson S. Schizophrenia and employment. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:337–349. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0762-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowbray CT, Collins ME, Bybee D. Supported education for individuals with psychiatric disabilities: long-term outcomes from and experimental study. Social Work Research. 1999;23:89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Mowbray CT, Collins ME. Effectiveness of supported education: current research findings. In: Mowbray CT, Furlong-Norman K, et al., editors. Supported Education: Models and Methods. Linthicum, M.D: International Association of Psychosocial Rehabilitation Services; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein KH, Subotnik KL, Turner LR, Ventura J. Individual placement and support for individuals with recent-onset schizophrenia: Integrating supported education and supported employment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2008;31:340–349. doi: 10.2975/31.4.2008.340.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins DV, Raines JA, Tschopp MK, Warner TC. Gainful employment reduces stigma toward people recovering from schizophrenia. Community Mental Health Journal. 2009;45:158–162. doi: 10.1007/s10597-008-9158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care: Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320:114–116. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi M, McNeil K, Firn M, Koletsi M, Perkins R, Singh SP. What are the benefits of evidence-based supported employment for patients with first-episode psychosis? Psychiatric Bulletin. 2004;28:281–284. [Google Scholar]

- Svedberg, et al. First-episode non-affective psychosis in a total urban population: a 5-year follow-up. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36:332–337. doi: 10.1007/s001270170037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasang H, Fung K, Corrigan P. Psychosocial and socio-demographic correlates of medication compliance among people with schizophrenia. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2009;40:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger KV, Anthony WA. Are families satisfied with services for young adult chronic patients? A recent survey and a proposed alternative. In: Pepper B, Ryglewicz H, editors. Advances in treating the young chronic patient New Directions for Mental Health Services. Vol. 21. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1984. pp. 91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger KV, Danley KS, Kohn L. Rehabilitation through education: A university-based continuing education program for young adults with psychiatric disabilities on a university campus. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1987;10:35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Unger KV. Handbook on supported education: Providing services for students with psychiatric disabilities. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brooks Publishing Co; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Waldheter EJ, Penn DL, Perkins DO, Mueser KT, Owens LW, Cook E. The graduated recovery intervention program for first episode psychosis: Treatment development and preliminary data. Community Mental Health Journal. 2008;44:443–455. doi: 10.1007/s10597-008-9147-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware NC, Hopper K, Tugenberg T, Dickey B, Fisher D. Connectedness and citizenship: redefining social integration. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:469–474. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.4.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware NC, Hopper K, Tugenberg T, Dickey B, Fisher D. A theory of social integration as quality of life. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59:27–33. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Oraganization. The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 update. 2008 RefType: Report.

- Yung AR, Killackey E, Hetrick SE, Parker AG, Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkoetter J, Purcell R, McGorry PD. The prevention of schizophrenia. International Review of Psychiatry. 2007;19:633–646. doi: 10.1080/09540260701797803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]