Abstract

Prostate specific promoters are frequently employed in gene mediated molecular imaging and therapeutic vectors to diagnose and treat castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) that emerges from hormone ablation therapy. Many of the conventional prostate specific promoters rely on the androgen axis to drive gene expression. However, considering the cancer heterogeneity and varying androgen receptor status, we herein evaluated the utility of prostate specific enhancing sequence (PSES), an androgen-independent promoter in CRPC. The PSES is a fused enhancer derived from the prostate specific antigen (PSA) and prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) gene regulatory region. We augmented the activity of PSES by the two-step transcriptional amplification (TSTA) system to drive the expression of imaging reporter genes for either bioluminescent or positron emission tomography (PET) imaging. The engineered PSES-TSTA system exhibits greatly elevated transcriptional activity, androgen-independency and strong prostate specificity, verified in cell culture and preclinical animal experimentations. These advantageous features of PSES-TSTA elicit superior gene expression capability for CRPC in comparison to the androgen-dependent PSA promoter driven system. In preclinical settings, we demonstrated robust PET imaging capacity of PSES-TSTA in a castrated prostate xenograft model. Moreover, intravenous administrated PSES-TSTA bioluminescent vector correctly identified tibial bone marrow metastases in 9 out of 9 animals while NaF- and FDG-PET was unable to detect the lesions. Taken together, this study demonstrated that the promising utility of a potent, androgen-independent and prostate cancer-specific expression system in directing gene-based molecular imaging in CRPC even in the context of androgen deprivation therapy.

Keywords: androgen independent, castration resistant, molecular imaging, bone metastasis, two step transcriptional amplification

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer for males in America. The disseminated disease remains a major cause of cancer-related morbidity and mortality [1]. Hormone ablation or androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is so far the most effective systemic treatment for patients with metastasis [2]. However, despite initial response to androgen withdrawal, castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) progression will occur within an average of 12-18 months in the majority of the cases [1]. Due to the unfortunate lack of cure for CRPC, the search for more effective treatment and diagnostic regimen deserves urgent attention.

Adenovirus (Ad) mediated molecular imaging and gene therapy vectors have been intensely studied to diagnose and treat CRPC for the past decade ([3] and reviewed by [4]). In these Ad vectors, prostate-specific promoters or enhancers such as the ones derived from prostate specific antigen (PSA), probasin, and human glandular kallikrein 2 (hK2) have been broadly used to drive tissue restricted transgene expression so as to ensure the minimum toxicity to normal and non-targeted organs [3]. Many of these promoters rely on the presence of testosterone and activated androgen receptor (AR) for transcription. A large volume of evidence has shown that AR remains active in CRPC via mechanisms such as AR amplification, mutation or intragenic rearrangement, upregulation of co-activators, ligand-independent activation of AR, as well as emergence of hyper-active AR splicing variants [5-8], theoretically supporting the use of AR driven promoters in castrated patients. However, prostate cancer exhibits great heterogeneity [9] and the functional status of AR vary amongst different metastatic lesions and primary tumors [10]. Moreover, under acute maximal ADT transcriptional activity of AR is expected to be strongly inhibited. A prostate cancer selective but less androgen- or AR-dependent promoter would likely be more active under this setting. Interestingly, the transcriptional regulation of the prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) gene differs dramatically from the PSA gene in that it is negatively regulated by androgen (i.e. androgen-suppressive)[11-12]. In addition to its proximal 1.2 kb promoter of PSMA, the prostate specificity and androgen-suppressive activity is highly regulated by its enhancer element (PSME), located in the third intron of the FOLH1 gene [13]. The expression of PSMA was found to be elevated in more malignant prostate cancer, CRPC, as well as tumor associated vasculature [14]. Although the transcriptional regulatory mechanism of PSME is still not well understood, several groups have exploited the strong prostate cancer selectivity of PSMA promoter/enhancer (PSMAP/E) to direct gene therapy against advanced prostate cancer [15-16]. Kao and colleagues have further advanced the prostate cancer-selective gene expression strategy by creating a chimeric prostate specific enhancing sequence (PSES) [17] that is comprised of gene regulatory elements from both the androgen-inducible PSA enhancer and the androgen-suppressive PSMA enhancer. Consequently, PSES can activate gene expression irrespectively of androgen status, making it a promising promoter for gene therapy in subjects with CRPC, especially considering the scenario of combining gene therapy under maximal ADT. The activity of PSES, however, is relatively limited compared to constitutive promoters [17].

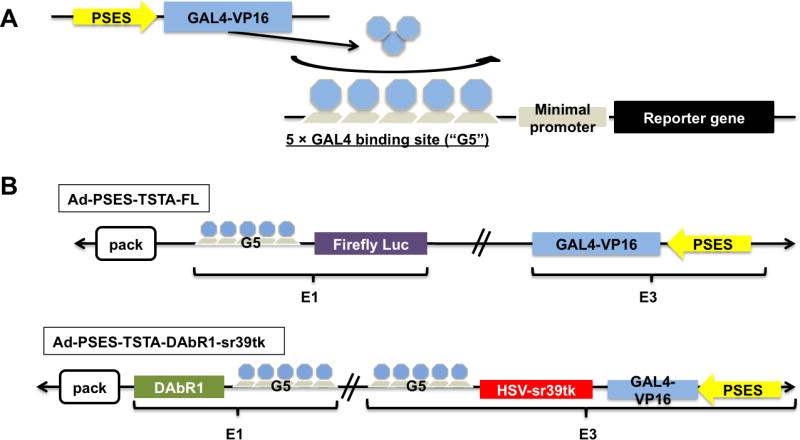

In this study we took advantage of the two step transcriptional amplification (TSTA) system to boost the transgene expression level of PSES. The principle of TSTA system is shown in Fig. 1A. In the first step, PSES drives the expression of the chimeric activator GAL4-VP16 [18] (GAL4 is the DNA binding domain while VP16 domain activates transcription), which then augments the transcription of the reporter genes upon recruitment to five GAL4 binding sites (G5). Two Ad vectors were generated with PSES-TSTA system regulating the expression of firefly luciferase (FL) or a variant of Herpes Simplex Virus-thymidine kinase (HSV-sr39tk) as bioluminescent and PET imaging reporter gene, respectively. Here, we demonstrated the benefits of prostate specificity and androgen-independency of the PSES-TSTA vectors to achieve sensitive and specific imaging in the challenging clinical scenario of metastatic CRPC.

Figure 1. Schematic of PSES-TSTA adenoviral vectors.

A. The PSES-TSTA system (see the text). B. Configuration of Ad vectors: the Ad-PSES-TSTA-FL contains PSES-GAL4VP16 in the E3 and G5-FL in the E1 region of adenoviral genome. The Ad-PSES-TSTA-DAbR1-sr39tk contains PSES-GAL4VP16 and G5-sr39tk (tail-to-tail configuration) in the E3 and G5-DAbR1 in the E1 region.

Materials and Methods

Adenoviral generation

Adenoviral vectors were constructed based on a modified AdEasy system – the AdNUEZ system, in which transgenes can be placed into the E3 region by multiple cloning sites. In Ad-PSES-TSTA-FL, the PSES-GAL4VP16 was constructed by replacing PSEBC with PSES in pBCnewVP2BS. PSES-GAL4VP16 was then cloned into pAdNUEZ vector to generate pAd-PSES-VP2EZ. pShuttleG5-FL was then used for recombination with pAd-PSES-VP2EZ. In Ad-PSES-TSTA-DAbR1-sr39tk, the E3 region was constructed by subcloning G5-sr39tk into pNEB193, followed by insertion of PSES-GAL4VP16 in tail-to-tail configuration. The two cassettes were then cut out by SpeI and placed into pAdNUEZ to generate pAd-G5sr39tkPSESVP2EZ. pShuttleG5-DAbR1 was constructed by replacing FL with DAbR1 in pShuttleG5-FL. Homologous recombination of pAdEZ and pShuttle was realized in E. Coli BJ5183 competent cells. Viral clones were screened, propagated, purified and titered as previously described [19].

Cell lines and cell culture experiments

All cell lines were cultured in medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The CWR22Rv1, LNCaP, C4-2, HeLa and A549 cells were maintained in RPMI1640. EMEM was used for DU145 cells. The VCaP, 293, MIA PaCa-2 and MDA-MB-231 cells were grown in DMEM. The LAPC-4 and LAPC-9 models were authenticated by UCLA Chancellor’s Animal Research Committee for the absence of mycoplasma. The VCaP cells were a kind gift from Dr. Robert Reiter. The other cell lines were obtained from AACR and were not further tested or authenticated. All cell culture experiments were conducted with cells at less than 35 passages after receipt. Synthetic androgen methylenetrienolone (R1881; NEN Life Science Products, Boston, MA) was used at 10 nmol/L. AR antagonist bicalutamide and MDV3100 was added to media as indicated at 10 μmol/L.

For in vitro luciferase assay, cells were seeded onto 24-well plates at 5×104 cells/well and infected the next day. All in vitro infection was done with multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. At 72 hrs post infection, the cells were harvested and lysed in passive lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI). FL luciferase activity was measured according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega) using a luminometer (Berthold Detection Systems, Pforzheim, Germany). Each value was normalized to cell number or protein amount and calculated as the average of triplicate samples. The activity was then normalized to that of Ad-PSES-TSTA-FL infected CWR22Rv1 cells cultured in R1881 condition so that different experiments can be compared across. Due to the similarity of infectivity among human cell lines, activity results were not adjusted.

For Western blot, 5×105 CWR22Rv1 and LNCaP cells were seeded into each well in 6-well plates, and infected with indicated virus the next day. 72 hrs post infection, cells were collected and lysed in passive lysis buffer, and cell lysates were fractionated on 4% to 12% gradient acrylamide gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and subjected to immunoblot analysis using polyclonal anti-HSV-tk antibody kindly provided by Dr. Margaret Black, polyclonal anti-human Fc antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA) and monoclonal anti β-actin A5316 antibody (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). Visualization was performed by BM Chemiluminescence (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) with HRP-conjugated respective antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Subcutaneous tumor xenograft experiments

Animal experiments were performed in accordance with the University of California Animal Research Committee guidelines. 5×105 CWR22Rv1 cells that were marked with lentivirus expressing CMV-driven renilla luciferase were implanted subcutaneously onto both flanks of 4- to 6-week-old female severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice (Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY) in matrigel (1:1 v/v; BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA). 1×107 Plaque forming units (PFU) viruses were intra-tumorally injected. Luciferase expression was monitored using an IVIS cooled CCD camera (Xenogen, Alameda, CA). Images were analyzed with IGOR-PRO LivingImage Software (Xenogen). In the LAPC-9 androgen-independent model, subcutaneous tumor explants were serially passaged in vivo in castrated male SCID-Beige mice (Taconic Farms). 1×107 PFU indicated virus was injected intra-tumorally followed by the same imaging and analysis procedure.

Orthotopic viral injection experiments

8 to 10-week-old male SCID (Taconic Farms) mice were used. 2×107 PFU respective Ad was injected into dorsal lobe of the prostate while the animals were anesthetized. Bioluminescent imaging (BLI) was performed at 7 days and 14 days post injection. Ex vivo imaging was done after sacrificing the animals and dissecting the indicated organs. Luciferase imaging and analysis were performed as described above.

PET imaging experiment

Subcutaneous LAPC-4 AI was serial-passaged in castrated SCID-Beige mice (Taconic Farms). Tumor chunks at the size of (3 mm)3 were cut and implanted subcutaneously onto the right shoulder of castrated SCID-Beige mice. 5 weeks later, a total of 1-2×109 PFU Ad-PSES-TSTA-sr39tk-DAbR1 was injected intra-tumorally in 4 consecutive days. 7 days after the initial infection, 18F-FHBG PET imaging was performed according to previously described procedures [19]. Animals were sacrificed after imaging.

Intra-tibial tumor experiment

4-6-week-old male SCID-Beige mice (Taconic Farms) were castrated by orchiectomy according to UCLA ARC procedure. 2 weeks later, 1×105 LAPC-4 AI [20] tumor cells were injected into the right tibial bone marrow in matrigel from underneath the knee. 6 weeks later, the animals received 1×108 PFU of Ad-CMV-GFP and 4×108 PFU Ad-PSES-TSTA-FL virus through tail vein with a 4-hr interval in between. The purpose of pre-dosing with irrelevant CMV-GFP virus is to blunt the Kupffer cells in the liver to improve transduction efficiency [21]. FL-mediated BLI was performed 4 days post viral administration. 18F-NaF and 18F-FDG PET imaging was done 6 and 11 days post infection, respectively. Briefly, for both 18F-NaF and 18F-FDG PET imaging, 70 μCi of probe was injected through the tail vein or i.p., respectively, and the animals were allowed to move around and excrete during 1-hr probe uptake. Afterwards, animals were given inhalation isoflurane anesthesia, placed in a prone position and imaged for 10 min in the microPET scanner. A 10-min CAT imaging session followed to provide structural information. All animals were sacrificed after the last imaging session, and tibial bone from both sides were removed and subjected to immunohistological staining with anti-pan-cytokeratin antibody (Bio-Genex, Fremont, CA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the one-tailed Mann Whitney Test. For all analyses, p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

PSES-TSTA activates gene expression under androgen deprivation or AR blockade

To examine the cell-targeted transcriptional activity of the PSES-TSTA system, we constructed two recombinant adenoviral vectors (Ads) that control the expression of the imaging reporter gene FL or HSV-sr39tk, respectively (Fig. 1B). Recapitulating extensive prior experiences ([18, 22-23]), the incorporation of TSTA system dramatically boosted the promoter activity of PSES at least three orders of magnitude compared to the parental PSES straight vector (Fig. S1A). Another advantageous feature of the TSTA system is its ability to drive the expression of multiple functional transgenes in the same vector simultaneously, exemplified by the Ad-PSES-TSTA- DAbR1-sr39tk vector (Fig. 1B). The DAbR1 gene (DOTA Antibody Reporter 1) encodes a membrane-anchored engineered antibody that can irreversibly bind to radiometal chelates [24]. Therefore, similar to HSV-sr39tk, it possesses both imaging and cytotoxic therapeutic capability. We have confirmed the expression of DAbR1 in Ad-PSES-TSTA- DAbR1-sr39tk (Fig S1B). However, we did not explore the utility of DAbR1 here as we are actively investigating the multi-modal imaging, suicide and radioimmune therapeutic capability of Ad-PSES-TSTA- DAbR1-sr39tk in a comprehensive treatment study of CRPC.

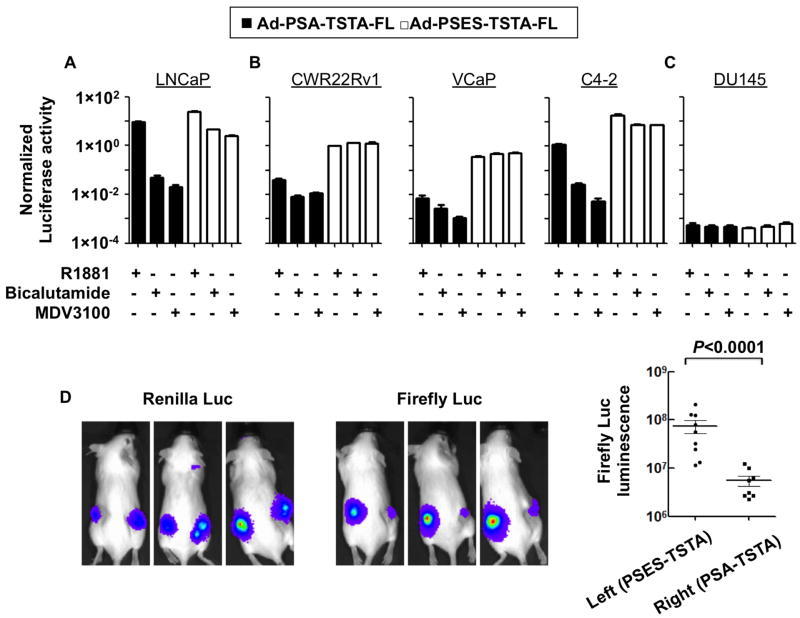

Next, we thoroughly evaluated the androgen-responsiveness of Ad-PSES-TSTA-FL in comparison to the enhanced PSA promoter-driven Ad-PSA-TSTA-FL (previously denoted as AdTSTA-FL, [18]) in androgen-dependent (AD) cell line LNCaP (Fig. 2A), AR-expressing yet androgen-independent (AI) CWR22Rv1, VCaP and C4-2 (Fig. 2B), as well as AR-negative prostate cancer cell line DU145 (Fig. 2C). AR expression was verified in Fig. S2A. To investigate the magnitude of androgen induction, the vector infected cells were cultured in media supplemented with either the synthetic androgen R1881 or AR antagonists. Both the first generation agent bicalutamide and the more potent second generation antagonist MDV3100 [25] were examined. In the highly AR-dependent, AD cell line LNCaP, bicalutamide and MDV3100 treatment substantially reduced PSA-TSTA-driven FL expression to 0.6% and 0.2%, respectively, compared to the R1881 condition, whereas the PSES-TSTA-driven FL only dropped down to 13% and 10%. In contrast, in the AI cell line CWR22Rv1, the presence of bicalutamide and MDV3100 decreased PSA-TSTA-FL activity to 28% and 32% of the R1881 condition, but the PSES-TSTA-driven FL expression was upregulated to 134% and 136%, respectively. Consistent results were observed in VCaP and C4-2 cells as well. In the DU145 cells that lack AR, both PSA-TSTA and PSES-TSTA vector were inactive (Fig. 2C). Remarkably, the absolute FL activity from the PSES-TSTA promoter was higher than that from PSA-TSTA in all the conditions tested in the AR-expressing tumor cells. The results in the DU145 cell line support that AR is necessary for the androgen-suppressible activity of PSME.

Figure 2. PSES-TSTA activates gene expression under androgen deficient conditions.

AR positive AD cell line LNCaP (A), AR positive AI cell lines CWR22Rv1, VCaP, and C4-2 (B) and AR negative AI cell line DU145 (C) were infected by indicated virus at MOI of 1. The cell lines were cultured in media containing either R1881 (at 10 nM) or indicated AR antagonist (bicalutamide or MDV3100 at 10μM). FL activity was examined 72 hrs afterwards. The activity of Ad-PSES-TSTA-FL in CWR22Rv1 with R1881 was set to 1 (absolute value = 4.64×1011 Relative Luminescence Units/mg, see Fig S1A) and the activity of all other cell lines is presented in reference to this level. D. 1×107 PFU Ad-PSA-TSTA-FL and Ad-PSES-TSTA-FL respectively were injected into the right and left CWR22Rv1 tumors on female SCID mice. Renilla luciferase imaging verified the establishment and similar volume of the two tumors. FL activity was monitored 4 days post viral injection. The absolute luminescence was plotted. Shown are three representative animals. One-tail t test was used.

Next, the gene expression capabilities of our vectors were examined in tumor-bearing animals. In our initial experiment, we implanted two CWR22Rv1 xenografts, stably expressing renilla luciferase (RL), onto both flanks of female severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice (n=9), using the low androgen level in female animals to mimic an androgen-deprived condition. The RL-mediated BLI verified the establishment of both tumors that grew to similar volume (Fig. 2D, left panel). Subsequently, equivalent doses of Ad-PSA-TSTA-FL and Ad-PSES-TSTA-FL vector were injected into the right and left tumor, respectively. In vivo FL-imaging verified the PSES-TSTA vector is about 10-fold more potent than the PSA-TSTA vector in CWR22Rv1 tumors in androgen-deficient conditions (Fig. 2D). To further substantiate the superior activity of PSES vector in an androgen-deprived setting, we injected Ad-PSES-TSTA-FL or Ad-PSA-TSTA-FL into solitary LAPC-9 AI (androgen-independent subline of LAPC-9) tumors established in castrated male SCID-Beige mice [20]. The intra-tumoral FL signal directed by the PSES-driven vector was nearly 100-fold higher than the PSA-driven vector (Fig. S2B-C). In summary, these results demonstrated that PSES-TSTA remained transcriptionally active regardless of androgen status. The Ad-PSES-TSTA-FL was able to achieve 10-100-fold higher gene expression level than the androgen-dependent PSA-TSTA-driven vector in several CRPC models.

PSES-TSTA retains stringent prostate tissue selectivity

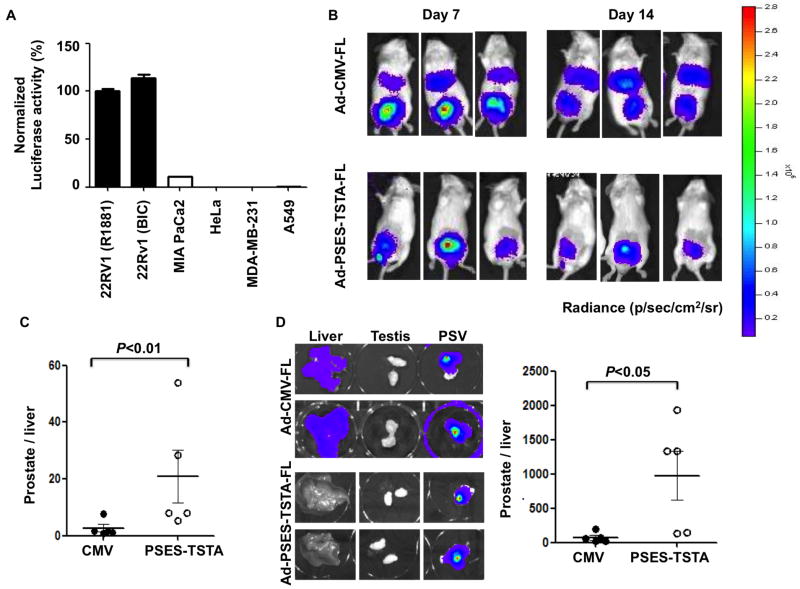

The prostate-specificity of PSES has been documented in previous reports [17]. However, it is necessary to evaluate the specificity of the amplified PSES-TSTA system, considering the introduction of the strong GAL4-VP16 transcriptional activator. First, a panel of cancer cell lines from various tissue origins was transduced with Ad-PSES-TSTA-FL. Robust expression was detected only in the prostate cancer cell line CWR22Rv1, while PSES-TSTA expression was restricted in non-prostatic cancer cell lines (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. PSES-TSTA is specific to prostate tissue.

A. Ad-PSES-TSTA-FL was used to transduce prostate (CWR22Rv1), pancreatic (MIA PaCa-2), cervical (HeLa), breast (MDA-MB-231) and lung (A549) cancer cell lines at MOI=1. FL activity was tested 72 hrs post infection. CWR22Rv1 cells were cultured in media containing 10 nM R1881 or 10 μM bicalutamide (BIC) as indicated. The activity of Ad-PSES-TSTA-FL in CWR22Rv1 with R1881 was set at 100%. B-D: 2×107 PFU indicated virus was injected into the dorsal lobes of prostate of male SCID mice. B. In vivo BLI image of three representative animals at 7 and 14 days post viral injection. C. The ratio of signal from the prostate region of interest (ROI) to liver ROI at day 14. D. Ex vivo image of liver, testis and prostate-seminal vesicle (PSV) in two representative animals and quantification of prostate-to-liver ROI ratio. One-tail t test was used.

To confirm the tissue-specificity in vivo, we injected Ad-PSES-TSTA-FL into the prostate of male SCID mice (n=5). The control cohort received the universal CMV promoter-driven vector. In vivo BLI was performed 7 and 14 days afterwards (Fig. 3B-C). Similar to our previous studies [26], we observed the systemic vector leakage despite the orthotopic injection manifested by the strong liver signal displayed from the CMV group. In contrast, Ad-PSES-TSTA-FL activated gene expression selectively in the prostate gland while inhibiting expression in the liver. Ex vivo imaging of harvested liver, testicles and prostate-seminal vesicles (PSV) again confirmed the prostate-specificity of PSES-TSTA seen in vivo (Fig. 3D). Collectively, our results demonstrated that the PSES-TSTA system activated gene expression only in prostate cancer cell lines, and that the in vivo transcriptional activity was restricted to the prostate.

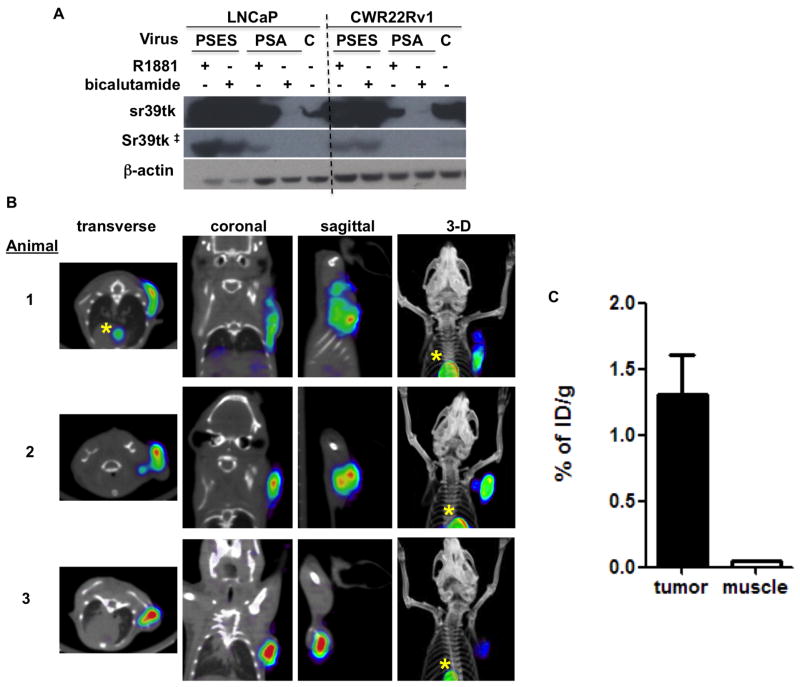

Directing PET imaging in castration resistant prostate cancer

BLI has very limited application as a whole-body imaging modality in clinical settings due to its poor tissue penetration and inability to provide quantitative signal in vivo. Previous experience with PET reporter genes such as HSV-sr39tk indicated it is less sensitive than bioluminescent reporter genes and therefore demands a very high level of gene expression [19]. Encouraged by the amplified activity of PSES-TSTA, we explored its ability to direct PET imaging in CRPC tumors. We first examined the magnitude of HSV-sr39tk gene product expressed by Ad-PSES-TSTA-DAbR1-sr39tk (Fig. 1B) in the LNCaP and CWR22Rv1 prostate cancer cell lines (Fig. 4A). Corroborating the previous result of the Ad-PSES-TSTA-FL vector (Fig. 2A-B), we observed that the PSES-TSTA is capable of achieving not only androgen-independent expression compared to PSA-TSTA, but also very robust expression of reporter gene, exceeding even the level achieved by the strong universal CMV vector.

Figure 4. PET imaging capacity of PSES-TSTA vector.

A. LNCaP and CWR22Rv1 cells were infected with Ad-PSES-TSTA -DAbR1-sr39tk (PSES), Ad-PSA-TSTA-sr39tk (PSA) or Ad-CMV-sr39tk (C) vectors and cultured in R1881 or bicalutamide supplemented media or regular media for CMV virus. Cells were lysed 72 hrs post infection and subjected to western blot. ‡, a shorter exposure time revealed the similar expression level of sr39tk by PSES-TSTA virus in androgen + and - conditions. B. Subcutaneous LAPC-4 tumor explants were passaged in vivo in castrated male SCID-Beige mice. A total of 1×109 PFU (animal 1 and 2) or 1.5×109 PFU (animal 3) of the Ad-PSES-TSTA-DAbR1-sr39tk vector was administered intra-tumorally via 4 sequential daily injections. 18F-FHBG PET imaging was performed 7 days after the first viral injection. *, accumulation of circulating probe 18F-FHBG in the heart. C. the %ID/g calculated from the tumor ROI or the muscle (background) ROI.

Next, we examined the in vivo PET imaging capability of Ad-PSES-TSTA-DAbR1-sr39tk with the use of the PET reporter probe 9-(4-[18F]-fluoro-3-hydroxymethylbutyl) guanine (18F-FHBG) in an androgen-independent subline of LAPC-4 prostate cancer cells (LAPC-4 AI) xenografts [20]. As shown in Figure 4B-C, intra-tumoral delivery of 1-1.5×109 PFU of Ad-PSES-TSTA-DAbR1-sr39tk was able to produce distinct tumor signal in all 3 castrated animals that were tested. The asterisks indicated accumulation of circulating probe in the cardiac blood pool and it is not attributed to non-specific gene expression from the PSES-TSTA system. Overall, these results support the feasibility of PSES-TSTA to direct tumor-specific PET imaging in CRPC patients, even in the setting of ADT.

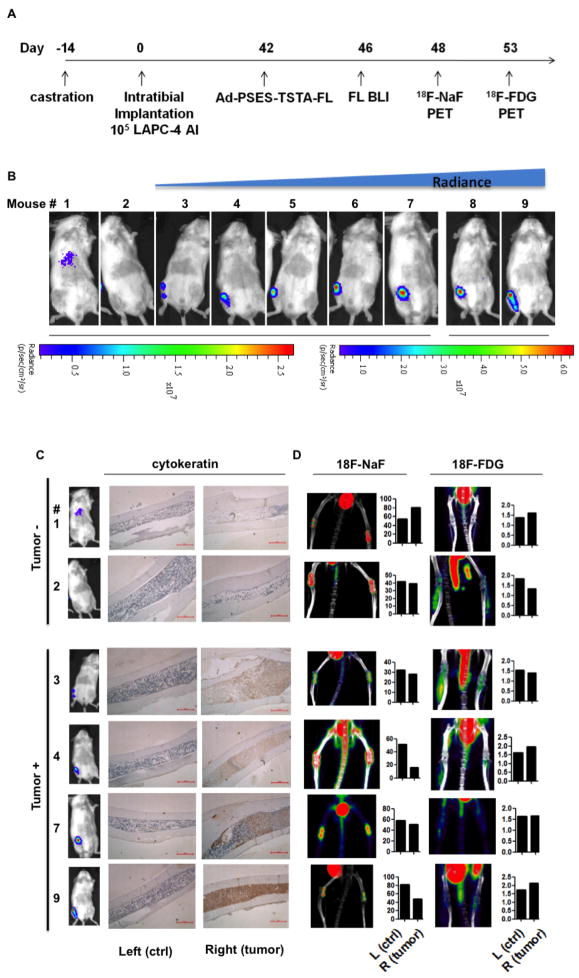

Image bony prostate cancer metastasis with systemic vector administration

Bone is the major site for prostate cancer metastasis [27-28]. Osseous involvement of this disease severely worsens the prognosis and quality of life. A reliable diagnostic tool to detect emergence of bony metastasis would be, therefore, highly valuable. To investigate the applicability of the PSES-TSTA in detecting bone metastasis, we injected LAPC-4 AI cells directly into the right tibia of nine castrated SCID-Beige mice, to develop osseous lesions [29]. As shown in the timeline of this study (Fig. 5A), Ad-PSES-TSTA-FL was administered through the tail vein 6 weeks after tumor cell implantation. This time point was chosen based on our previous experience showing that, although there is some variability in the rate of tumor establishment with this model, a majority of osseous lesions will be established in this time frame. In vivo BLI detected positive FL signals in the right tibia in 7 out of the 9 animals (Fig. 5B). Remarkably, immunohistochemistry staining with a human epithelial cell-specific marker, pan-cytokeratin, demonstrated that the 2 negative animals indeed failed to establish any tumor in the bone (Fig. 5C). On the other hand, the presence of prostate cancer in the 7 “positive” animals was confirmed by either pan-cytokeratin staining or gross observation of the bone (Fig. 5C and Fig. S3). Furthermore, this imaging approach qualitatively reflects the volume of tumor mass because the magnitude of FL luminescence roughly correlated with the intensity of cytokeratin staining of the tumor mass (Fig. 5C). Importantly, we observed no emission at any other site, albeit a negligible level in the liver of 1 animal, demonstrating the high prostate cancer-specificity of PSES-TSTA (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. PSES-TSTA imaging vector mediated detection of castration-resistant bony prostate cancer metastasis.

A. Time frame: 4-5-wk-old male SCID-Beige mice were castrated. 1×105 LAPC-4 AI tumor cells were injected into the right tibiae. Forty two days later, the animals received 1×108 PFU of Ad-CMV-GFP (to blunt the vector uptake by Kupffer cells), followed by 4×108 PFU Ad-PSES-TSTA-FL through tail vein 4 hrs later. FL BLI, 18F-NaF and 18F-FDG PET-CT imaging was performed at indicated times. B. Ad-PSES-TSTA directed FL BLI. Mice are displayed according to radiance intensity emitted from the right tibiae. The 2 mice on the left were negative while the other 7 mice were positive for tumor. Note the difference in intensity scales for mice 1-7, and mice 8-9. C. Immunohistochemistry staining of the right tibiae of six representative animals using a human-specific pan-cytokeratin antibody. D. 18F-NaF and 18F-FDG PET signals from tumor bearing mice. The quantification represents % Injection Dose/g from left (control) and right (tumor injected) tibial ROI. Bar, 500 μm.

Next, we decided to compare the PSES-TSTA approach to current clinical PET-based imaging technologies. We assessed the diagnostic ability of two conventional PET tracers 18F-NaF (sodium fluoride) and 18F-FDG to image these animals bearing osseous lesions 2 and 7 days after the BLI (Fig 5A). The fluoride ion tends to deposit at active bone remodeling sites, such as cancer osseous metastatic lesions, where intertwined interactions of cancer cells, osteoblasts and osteoclasts dynamically occur. Thus, there is an increased interest to use 18F-NaF as a tracer to assess metastatic bone lesions for prostate and other cancerous malignancies [29-30]. However, as shown in the left panel of Fig. 5D, 18F-NaF PET-CT failed to identify the tumor-bearing tibia in the 6 animals examined. On the other hand, due to the well known Warburg effect of heightened glucose metabolism in most cancer, 18F-FDG has been used as the standard PET-imaging tracer in oncology [29, 31]. Hence, we also assessed the detection capability of 18F-FDG PET-CT for bone metastases (Fig. 5D, right panel). Out of the 6 animals examined, 18F-FDG PET-imaging was unable to distinguish between animals with histologically proven lesions from those without lesions. Nor could 18F-FDG distinguish between the lesion-positive (right) and -negative (left) tibia within the same animal.

We conclude that that systemically injected Ad-PSES-TSTA-FL and subsequent BLI can detect an experimental prostate cancer osseous metastasis model with high degree of accuracy (9 out of 9 animals). This type of transcription-based imaging could be more specific than 18F-FDG and 18F-NaF PET-CT, two standard methods currently used in clinics.

Discussion

In the battle against advanced prostate cancer, there is an urgent and unmet need for a selective imaging modality. The transcription-based molecular imaging approach is particularly advantageous in its ability to be tailored to the molecular and genetic alterations in cancer [32-33]. Recent pre-clinical and clinical evidence demonstrate that AR signaling is required to sustain the growth of prostate cancer, even in CRPC [5-9, 34]. Based on this property, we and others employed the AR-dependent PSA promoter to drive reporter gene-based imaging and demonstrated the feasibility of this approach to monitor dynamic AR transcription function in vivo, to image CRPC and metastatic diseases [33, 35-37]. Although the TSTA system can boost the activity of the PSA promoter and facilitate imaging of CRPC tumors, we speculate that the incorporation of an androgen-independent and cancer-selective gene regulatory element could be more efficacious in driving the imaging reporter, especially in the context of maximal androgen blockade therapy. To this end, the enhancer element of the PSMA gene (PSME) appeared to be particularly promising due to its prostate cancer-specificity and its unique androgen-suppressible transcriptional activity [12]. In this study we applied the TSTA amplification to the PSES promoter, which fused the PSME with the PSA enhancer element. The resulting PSES-TSTA vectors were able to achieve dramatically elevated transcriptional potency compared to the parental PSES promoter alone. Moreover, they were capable of directing androgen-independent and prostate cancer-specific expression. As a consequence of their augmented capabilities, we observed that the utility of the PSES-TSTA vectors in imaging application for CRPC was also expanded. For instance, we demonstrated that the PSES-TSTA vector expressing the HSV-sr39tk gene elicits robust PET signals in CRPC tumors. Moreover, systemic delivery of Ad-PSES-TSTA-FL and subsequent BLI was capable of detecting bony CRPC metastases in a manner more sensitive and specific than current, conventional PET-imaging modalities. The ability of the PSES-TSTA vector to accomplish this challenging task of detecting metastatic lesions within the systemic circulation further affirms the CRPC-selective expression capability of the PSES-TSTA vector.

At this current juncture, the mechanism of the intriguing androgen-suppressible activity of PSME is not well understood. It is clear that linkage of PSME to the PSA enhancer countered the highly androgen/AR-induced activity of the PSA enhancer, especially in the context of acute AR blockade (Fig. 2). In response to treatment with AR antagonists, the activity of the PSA enhancer-driven reporter (Ad-PSA-TSTA-FL) was drastically inhibited in both AD LNCaP cell line and castration resistant AR-positive cell lines. Moreover, the magnitude of PSA-TSTA activity suppression correlated with the potency of AR antagonists (Fig. 2A), as the second generation antagonist MDV3100 was reported to be nearly 10-fold more active than bicalutamide, the first generation agent [25]. In contrast, the PSES-TSTA-mediated luciferase signal was not sensitive to AR blockade, even under the more efficacious MDV3100 treatment. The activity of the PSA enhancer component of PSES can be appreciated in highly androgen- and AR-dependent settings. For instance, in LNCaP cells in the presence of androgen, the activity of PSA-TSTA vector is almost equivalent to the PSES-TSTA vector. However, in CRPC models, despite ample level of androgen, the expression level of PSA-TSTA remains significantly reduced (by over 100-fold) when compared to PSES-TSTA. This result again highlights that, in the context of suppressed AR function, the contribution of PSME driven transcriptional activity will play a dominant role. Interestingly, the inability of PSES-TSTA to function in AR-negative DU145 (Fig. 2C) and PC-3 cell lines (data not shown) reaffirms previous reports that the androgen-suppressible activity of PSME is likely mediated through AR by an indirect mechanism [14]. Further investigation of the transcriptional regulation of PSME is needed to resolve the interesting androgen-suppressive and prostate cancer-selective activity of this enhancer element.

The advanced lethal stage of prostate cancer has a particular propensity to metastasize to bone, severely impacting the patient’s quality of life [27-28, 38]. The affinity for bone is likely due to pro-tumorigenic growth factors and a favorable environment produced as a result of the reciprocal interactions between prostate cancer and bone cells [39]. ADT can induce factors that promote the process of prostate cancer bone metastasis [40]. The current established clinical standard for imaging bone metastasis is whole-body planar bone scan with 99mTc-methylenediphosphonate (MDP). Due to the low spatial resolution of bone scans, there is a favorable trend towards using 18F-NaF PET/CT with the hope of improving the sensitivity and resolution of bone metastasis detection [41]. Several drawbacks of these two imaging modalities result from the fact that uptake of 99mTc-MDP and 18F-NaF are reliant on bone remodeling, a later event in the bone metastatic process [42]. For instance, both 99mTc-MDP bone scan and 18F-NaF PET/CT will be unable to directly assess tumor volume especially in the early stage of metastasis or to detect concomitant visceral metastatic lesions. These reasons could explain why specific detection of prostate cancer metastases in the tibial bone marrow was feasible via intravenous Ad-PSES-TSTA-FL injection/BLI but not with 18F-NaF PET/CT. These data suggest that our model represents an early stage of CRPC osseous metastasis, since we were unable to detect any bony deformity by inspection (Fig. S3) or CT scan. In addition, the animals did not exhibit any abnormality in ambulation. The histological analyses of the metastatic lesions also revealed the involvement of cancer cells in the bone marrow, but not the cortex of the bone. The clinical experience with FDG PET in detecting prostate cancer is equivocal [43-44]. Our experience indicates that human prostate cancer xenografts are not particularly avid in uptake of 18F-FDG (data not shown). The current study further demonstrated this point in bone marrow metastases of CRPC LAPC-4 tumor.

Several challenges are anticipated in the clinical translation of adenoviral-based reporter gene imaging described here. Significant hurdles to overcome will include the immunogenicity of the adenoviral vector. In particular, the pre-existing immunity in a large proportion of the human population against the Ad5 serotype used here will likely induce rapid clearance of the vector. In addition, interaction of virus with blood borne factors in the circulation could result in liver sequestration and thus hinder its biodistribution in human patients [45-46]. Recent advances shed light on promising strategies to overcome these challenges. For instances, based on the recent reported ultra-high resolution of viral capsid structure [47], one could mutate the virion capsule residues to ablate immunogenic epitopes, disrupt the interactions with circulating factors, or insert targeting ligands. The use of bi-specific molecule has been successful in not only de-targeting the native tropism of adenovirus in vivo but also re-targeting the vector to tumor cell surface antigens [48]. We and others have obtained promising results by applying advanced polymer technologies to coat the virus to blunt its immunogenicity as well as to enhance cell-targeted entry [49]. The use of transient immunosuppression regimen has established traction in overcoming the immunogenicity issues of Ad gene therapy to facilitate long term administration [50]. In a very recent study, Bhang and colleagues demonstrated that a non-viral cationic polymer vector can achieve efficient gene delivery and imaging to detect systemic metastasis in melanoma and breast cancer models [32]. Their results also reaffirm the great specificity of transcription-based molecular imaging.

In summary, we report here the development of PSES-TSTA as an androgen-independent and prostate cancer-specific gene expression system. The transcriptional amplification strategy undertaken boosted the expression of both a bioluminescent reporter gene and a PET reporter gene, to achieve sensitive and prostate cancer-specific molecular imaging in pre-clinical models of CRPC. The potency, cell-selectivity and diagnostic potential of PSES-TSTA vectors was illustrated by the ability of a PSES-TSTA imaging vector to detect early CRPC bone marrow metastases following systemic vector administration. The PSES-TSTA vectors can be modified to simultaneously express imaging reporter genes and cytotoxic therapeutic genes. Hence, the implementation of multipronged therapeutic strategy such as combined ADT with image-guided gene therapy to treat advanced and even metastatic CRPC may be feasible, using the PSES-TSTA system described in this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Breanne Karanikolas, Oh-Joon Kwon and Jennifer Kuo for technical assistance, Dr. Larry Pang for technical insight in PET imaging, Dr. Robert Reiter and Joyce Yamashiro for sharing of research reagents. We deeply appreciate Drs. Harvey Herschman, Michael Carey, and Anna Wu for their helpful comments on the manuscript. This work is supported by NCI/NIH RO1 CA101904-01 and SPORE program P50 CA092131 (to L.W). ZKJ is supported by a UCLA JCCC fellowship.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

References

- 1.Lassi K, Dawson NA. Update on castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2010 doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283380939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang HQ, Yang B, Xu CL, Wang LH, Zhang YX, Xu B, et al. Differential phosphoprotein levels and pathway analysis identify the transition mechanism of LNCaP cells into androgen-independent cells. Prostate. 2010;70(5):508–17. doi: 10.1002/pros.21085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Figueiredo ML, Kao C, Wu L. Advances in preclinical investigation of prostate cancer gene therapy. Mol Ther. 2007;15(6):1053–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Vrij J, Willemsen RA, Lindholm L, Hoeben RC, Bangma CH, Barber C, et al. Adenovirus-derived vectors for prostate cancer gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther. 2010;21(7):795–805. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Attar RM, Takimoto CH, Gottardis MM. Castration-resistant prostate cancer: locking up the molecular escape routes. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(10):3251–5. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Attard G, Reid AH, Olmos D, de Bono JS. Antitumor activity with CYP17 blockade indicates that castration-resistant prostate cancer frequently remains hormone driven. Cancer Res. 2009;69(12):4937–40. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, Alsagabi M, Fan D, Bova GS, Tewfik AH, Dehm SM. Intragenic Rearrangement and Altered RNA Splicing of the Androgen Receptor in a Cell-Based Model of Prostate Cancer Progression. Cancer Res. 2011;71(6):2108–17. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun S, Sprenger CC, Vessella RL, Haugk K, Soriano K, Mostaghel EA, et al. Castration resistance in human prostate cancer is conferred by a frequently occurring androgen receptor splice variant. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(8):2715–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI41824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niu Y, Chang TM, Yeh S, Ma WL, Wang YZ, Chang C. Differential androgen receptor signals in different cells explain why androgen-deprivation therapy of prostate cancer fails. Oncogene. 2010;29(25):3593–604. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah RB, Mehra R, Chinnaiyan AM, Shen R, Ghosh D, Zhou M, et al. Androgen-independent prostate cancer is a heterogeneous group of diseases: lessons from a rapid autopsy program. Cancer Res. 2004;64(24):9209–16. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Israeli RS, Powell CT, Fair WR, Heston WD. Molecular cloning of a complementary DNA encoding a prostate-specific membrane antigen. Cancer Res. 1993;53(2):227–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright GL, Jr, Grob BM, Haley C, Grossman K, Newhall K, Petrylak D, et al. Upregulation of prostate-specific membrane antigen after androgen-deprivation therapy. Urology. 1996;48(2):326–34. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(96)00184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Keefe DS, Su SL, Bacich DJ, Horiguchi Y, Luo Y, Powell CT, et al. Mapping, genomic organization and promoter analysis of the human prostate-specific membrane antigen gene. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1443(1-2):113–27. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00200-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghosh A, Heston WD. Tumor target prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) and its regulation in prostate cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2004;91(3):528–39. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeng H, Wei Q, Huang R, Chen N, Dong Q, Yang Y, et al. Recombinant adenovirus mediated prostate-specific enzyme pro-drug gene therapy regulated by prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) enhancer/promoter. J Androl. 2007;28(6):827–35. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.107.002519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang P, Zeng H, Wei Q, Lu Y, Li X, Wang J, et al. Improved effects of a double suicide gene system on prostate cancer cells by targeted regulation of prostate-specific membrane antigen promoter and enhancer. Int J Urol. 2008;15(5):442–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2008.02034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SJ, Kim HS, Yu R, Lee K, Gardner TA, Jung C, et al. Novel prostate-specific promoter derived from PSA and PSMA enhancers. Mol Ther. 2002;6(3):415–21. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sato M, Johnson M, Zhang L, Zhang B, Le K, Gambhir SS, et al. Optimization of adenoviral vectors to direct highly amplified prostate-specific expression for imaging and gene therapy. Mol Ther. 2003;8(5):726–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson M, Sato M, Burton J, Gambhir SS, Carey M, Wu L. Micro-PET/CT monitoring of herpes thymidine kinase suicide gene therapy in a prostate cancer xenograft: the advantage of a cell-specific transcriptional targeting approach. Mol Imaging. 2005;4(4):463–72. doi: 10.2310/7290.2005.05154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein KA, Reiter RE, Redula J, Moradi H, Zhu XL, Brothman AR, et al. Progression of metastatic human prostate cancer to androgen independence in immunodeficient SCID mice. Nat Med. 1997;3(4):402–8. doi: 10.1038/nm0497-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tao N, Gao GP, Parr M, Johnston J, Baradet T, Wilson JM, et al. Sequestration of adenoviral vector by Kupffer cells leads to a nonlinear dose response of transduction in liver. Mol Ther. 2001;3(1):28–35. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dzojic H, Cheng WS, Essand M. Two-step amplification of the human PPT sequence provides specific gene expression in an immunocompetent murine prostate cancer model. Cancer Gene Ther. 2007;14(3):233–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7701007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ray S, Paulmurugan R, Patel MR, Ahn BC, Wu L, Carey M, et al. Noninvasive imaging of therapeutic gene expression using a bidirectional transcriptional amplification strategy. Mol Ther. 2008;16(11):1848–56. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei LH, Olafsen T, Radu C, Hildebrandt IJ, McCoy MR, Phelps ME, et al. Engineered antibody fragments with infinite affinity as reporter genes for PET imaging. J Nucl Med. 2008;49(11):1828–35. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.054452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tran C, Ouk S, Clegg NJ, Chen Y, Watson PA, Arora V, et al. Development of a second-generation antiandrogen for treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Science. 2009;324(5928):787–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1168175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson M, Huyn S, Burton J, Sato M, Wu L. Differential biodistribution of adenoviral vector in vivo as monitored by bioluminescence imaging and quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Hum Gene Ther. 2006;17(12):1262–9. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ara T, Declerck YA. Interleukin-6 in bone metastasis and cancer progression. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(7):1223–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu Y, Chen Q, Corey E, Xie W, Fan J, Mizokami A, et al. Activation of MCP-1/CCR2 axis promotes prostate cancer growth in bone. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2009;26(2):161–9. doi: 10.1007/s10585-008-9226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsu WK, Virk MS, Feeley BT, Stout DB, Chatziioannou AF, Lieberman JR. Characterization of osteolytic, osteoblastic, and mixed lesions in a prostate cancer mouse model using 18F-FDG and 18F-fluoride PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2008;49(3):414–21. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.045666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Withofs N, Grayet B, Tancredi T, Rorive A, Mella C, Giacomelli F, et al. 18F-fluoride PET/CT for assessing bone involvement in prostate and breast cancers. Nucl Med Commun. 2010;32(3):168–76. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e3283412ef5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu EY, Muzi M, Hackenbracht JA, Rezvani BB, Link JM, Montgomery RB, et al. C11-Acetate and F-18 FDG PET for Men With Prostate Cancer Bone Metastases: Relative Findings and Response to Therapy. Clin Nucl Med. 2011;36(3):192–8. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e318208f140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhang HE, Gabrielson KL, Laterra J, Fisher PB, Pomper MG. Tumor-specific imaging through progression elevated gene-3 promoter-driven gene expression. Nat Med. 2011;17(1):123–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sato M, Johnson M, Zhang L, Gambhir SS, Carey M, Wu L. Functionality of androgen receptor-based gene expression imaging in hormone refractory prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(10):3743–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scher HI, Beer TM, Higano CS, Anand A, Taplin ME, Efstathiou E, et al. Antitumour activity of MDV3100 in castration-resistant prostate cancer: a phase 1-2 study. Lancet. 2010;375(9724):1437–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60172-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang L, Johnson M, Le KH, Sato M, Ilagan R, Iyer M, et al. Interrogating androgen receptor function in recurrent prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63(15):4552–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burton JB, Johnson M, Sato M, Koh SB, Mulholland DJ, Stout D, et al. Adenovirus-mediated gene expression imaging to directly detect sentinel lymph node metastasis of prostate cancer. Nat Med. 2008;14(8):882–8. doi: 10.1038/nm.1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams JY, Johnson M, Sato M, Berger F, Gambhir SS, Carey M, et al. Visualization of advanced human prostate cancer lesions in living mice by a targeted gene transfer vector and optical imaging. Nat Med. 2002;8(8):891–7. doi: 10.1038/nm743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooper CR, Chay CH, Gendernalik JD, Lee HL, Bhatia J, Taichman RS, et al. Stromal factors involved in prostate carcinoma metastasis to bone. Cancer. 2003;97(3 Suppl):739–47. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Logothetis CJ, Navone NM, Lin SH. Understanding the biology of bone metastases: key to the effective treatment of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(6):1599–602. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee YC, Cheng CJ, Huang M, Bilen MA, Ye X, Navone NM, et al. Androgen depletion up-regulates cadherin-11 expression in prostate cancer. J Pathol. 2010;221(1):68–76. doi: 10.1002/path.2687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Even-Sapir E, Metser U, Mishani E, Lievshitz G, Lerman H, Leibovitch I. The detection of bone metastases in patients with high-risk prostate cancer: 99mTc-MDP Planar bone scintigraphy, single- and multi-field-of-view SPECT, 18F-fluoride PET, and 18F-fluoride PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2006;47(2):287–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toegel S, Hoffmann O, Wadsak W, Ettlinger D, Mien LK, Wiesner K, et al. Uptake of bone-seekers is solely associated with mineralisation! A study with 99mTc-MDP, 153Sm-EDTMP and 18F-fluoride on osteoblasts. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33(4):491–4. doi: 10.1007/s00259-005-0026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu IJ, Zafar MB, Lai YH, Segall GM, Terris MK. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography studies in diagnosis and staging of clinically organ-confined prostate cancer. Urology. 2001;57(1):108–11. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00896-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oyama N, Akino H, Suzuki Y, Kanamaru H, Miwa Y, Tsuka H, et al. Prognostic value of 2-deoxy-2-[F-18]fluoro-D-glucose positron emission tomography imaging for patients with prostate cancer. Mol Imaging Biol. 2002;4(1):99–104. doi: 10.1016/s1095-0397(01)00065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greig JA, Buckley SM, Waddington SN, Parker AL, Bhella D, Pink R, et al. Influence of coagulation factor x on in vitro and in vivo gene delivery by adenovirus (Ad) 5, Ad35, and chimeric Ad5/Ad35 vectors. Mol Ther. 2009;17(10):1683–91. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carlisle RC, Di Y, Cerny AM, Sonnen AF, Sim RB, Green NK, et al. Human erythrocytes bind and inactivate type 5 adenovirus by presenting Coxsackie virus-adenovirus receptor and complement receptor 1. Blood. 2009;113(9):1909–18. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-178459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu H, Jin L, Koh SB, Atanasov I, Schein S, Wu L, et al. Atomic structure of human adenovirus by cryo-EM reveals interactions among protein networks. Science. 2010;329(5995):1038–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1187433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li HJ, Everts M, Yamamoto M, Curiel DT, Herschman HR. Combined transductional untargeting/retargeting and transcriptional restriction enhances adenovirus gene targeting and therapy for hepatic colorectal cancer tumors. Cancer Res. 2009;69(2):554–64. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan M, Du J, Gu Z, Liang M, Hu Y, Zhang W, et al. A novel intracellular protein delivery platform based on single-protein nanocapsules. Nat Nanotechnol. 2010;5(1):48–53. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Homicsko K, Lukashev A, Iggo RD. RAD001 (everolimus) improves the efficacy of replicating adenoviruses that target colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65(15):6882–90. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.