Abstract

An understanding of gene function often relies upon creating multiple kinds of alleles. Functional analysis in Candida albicans, a major fungal pathogen, has generally included characterization of mutant strains with insertion or deletion alleles and over-expression alleles. Here we use in C. albicans another type of allele that has been employed effectively in the model yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a “Decreased Abundance by mRNA Perturbation” (DAmP) allele (Yan et al., 2008). DAmP alleles are created systematically through replacement of 3′ noncoding regions with nonfunctional heterologous sequences, and thus are broadly applicable. We used a DAmP allele to probe the function of Sun41, a surface protein with roles in cell wall integrity, cell-cell adherence, hyphal formation, and biofilm formation that has been suggested as a possible therapeutic target (Firon et al., 2007; Hiller et al., 2007; Norice et al., 2007). A SUN41-DAmP allele results in approximately 10-fold reduced levels of SUN41 RNA, and yields intermediate phenotypes in most assays. We report that a sun41Δ/Δ mutant is defective in biofilm formation in vivo, and that the SUN41-DAmP allele complements that defect. This finding argues that Sun41 may not be an ideal therapeutic target for biofilm inhibition, since a 90% decrease in activity has little effect on biofilm formation in vivo. We anticipate that DAmP alleles of C. albicans genes will be informative for analysis of other prospective drug targets, including essential genes.

Keywords: Candida albicans, DAmP, Biofilm, SUN41

1. Introduction

The fungus Candida albicans is of interest due to its pathogenic potential as well as its biological properties (Pfaller and Diekema, 2007; Rex et al., 2000). It lacks a facile “forward genetics” system, in part because it is a diploid that lacks a complete sexual cycle (Alby et al., 2009; Epp et al., 2010; Soll et al., 2003). However, targeted insertion or deletion mutant strains have enabled gene function analysis (Blankenship et al. 2010; Epp et al., 2010; Homann et al., 2009; Nobile and Mitchell, 2005). There are also many examples where valuable functional information has come from reduced gene expression in insertion/deletion heterozygotes, or increased gene expression from promoter replacement strains (Fu et al., 2008; Nobile and Mitchell, 2005; Xu et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2005) (Care et al., 1999; Oh et al.; Roemer et al., 2003; Uhl et al., 2003). However, there remain cases in which these gene expression levels may not fully inform or test functional hypotheses. For example, a heterozygous insertion/deletion mutant may not have a discernible phenotype, while a homozygous insertion/deletion mutant may have too severe a phenotype – lethality or pleiotropy – to permit a detailed functional interpretation.

In this report we have implemented a systematic strategy to create hypomorphs, or alleles with reduced activity. The strategy is to create a “Decreased Abundance by mRNA Perturbation” (DAmP) allele (Muhlrad and Parker, 1999; Yan et al., 2008). DAmP alleles are created through replacement of 3′ noncoding regions with nonfunctional heterologous sequences, and thus are applicable to almost all genes. The altered 3′ regions lack polyadenylation signals or other sequences that stabilize the mRNA, thus causing reduced mRNA accumulation (Muhlrad and Parker, 1999). Such alleles have been useful for large scale studies in S. cerevisiae (Yan et al., 2008), and we anticipate that they will be useful for C. albicans.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Growth conditions

All C. albicans and S. cerevisiae strains were passaged in liquid YPD (2% dextrose, 2% Bacto Peptone, 1% yeast extract) at 220 rpm agitation at 30°C. Strains were grown on YPD solid medium (YPD broth, agar) at 30°C. Transformants were selected on synthetic dextrose medium (2% dextrose,0.67% yeast nitrogen base plus ammonium sulfate), to which the necessary auxotrophic supplements were added. Spider medium was prepared as previously described (Blankenship et al. 2010).

2.2 Plasmids and C. albicans strains

To create pCTNB4, 2,011 bps of upstream sequence of SUN41 along with the open reading frame minus the stop codon was amplified by PCR using primers SUN41compl and SUN41 3 tag (Table 1). The pYES2.1 TOPO TA Expression kit (Invitrogen) was used to clone the fragment into a pYES2.1/V5-His-TOPO vector to create pCTNB4 which contains the CYC1 3′ UTR sequence 5′ ATCATGTAATTAGTTATGTCACGCTTACATTCACGCCCTCCTCCCACATCCGCTCTAACCGAAAAGGAAGGAGTTAGACAACCTGAAGTCTAGGTCCCTATTTATTTTTTTTAATAGTTATGTTAGTATTAAGAACGTTATTTATATTTCAAATTTTTCTTTTTTTTCTGTACAAACGCGTGTACGCATGTAACATTATACTGAAAACCTTGCTTGAGAAGGTTTTGGGACGCTCGAAGGCTTTAATTTGCAAGCT 3′ (Norice, 2008). The SUN41 DAmP strain was created in several sequential steps. First, we PCR-amplified the promoter region, the coding region of SUN41 and V5 tag from plasmid pCTNB4, with primers pYES2.1-recomb-up and pYES2.1-NOT-recomb-dn (Table 1). The resulting amplicon was inserted by recombination in S. cerevisiae into a NotI-digested pDDB78 plasmid (Spreghini et al., 2003) resulting in plasmid pNY100. Following the SUN41 ORF is vector sequence 5′ GCGGCCGCCACCGCGGTGGAGCTCCAATTCGCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTACAATTCACTGGCCGTCGTTTTACAACGTCGTGACTGGGAAAACCCTGGCGTTACCCAACTTAATCGCCTTGCAGCACATCCCCCCTTCGCCAGCTGGCGTAATAGCGAAGAGGCCCGCACCGATCGCCCTTCCCAACAGTTGCGCAGCCTGAATGGCGAATGGCGCGACGCGCCCTGTAGCGGCGCATTAAGCGCGGCGGGTGTG 3′. The NYY100 strain was created by transforming CTN41 with a Nru1-digested pNY100. The complemented sun41Δ/Δ + pSUN41-V5 strain NYY105was created by transforming CTN41 with a NruI-digested pCTNB6.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study

| Sun41 detect for | TCA ACT GGT GGT TCT GGT |

| Sun41 detectback0 | AGT ACT ACC ACC TCC AAC AAC GGT |

| pYES2.1 recomb up | GCC AGG GTT TTC CCA GTC ACG TTG TAA AAC GAC GGC CGT AAT ACG ACT CAC TAT AGG G |

| pYES2.1 NOT recomb dn | GAT ATC GAA TTC CTG CAG CCC GGG GGA TCC ACT AGT TCT AGC GGC CGC AGA AAC TCA ATG GTG ATG GT |

| SUN41 RTforw | TGC CAA AGT GGT ATG TCC AA |

| SUN41 rtbak | TTC AAT GGA GCC CAG TTA CC |

| JRB227 | ATC CCA CAA GGA CTG GAG A |

| JRB228 | GCA GAA GCT TTA GCA ACG TG |

| SUN41compL | CATGTCATCAACAACTGTACTC |

| SUN41 3 tag | ATTATACAAGACAAAGTCAGC |

2.3 RNA purification and quantitative RTPCR

Strains were grown overnight and diluted to an OD600 of 0.2 in 50 mL of YPD. Cultures were grown at 30°C with shaking until density reached OD600 of ~0.8. Cells were harvested by vacuum filtration and flash frozen in a dry ice/ethanol bath. RNA was extracted using the RiboPure-Yeast kit (Ambion) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were beaten with a Next Advance Bullet Blender for 3 minutes at 4°C to ensure complete lysis. 10 μg of the isolated RNA was DNase treated (Ambion), and first-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with the AffinityScript multiple temperature cDNA synthesis kit (Stratagene). A control reaction lacking the reverse transcriptase was performed to ensure absence of DNA contamination. Quantification was then performed through quantitative PCR for SUN41 and the reference transcript, TDH3. All data were normalized to TDH3. Primers used for PCR amplification were SUN41 RTforward, SUN41 rtback, JRB227 (TDH3), and JRB228 (TDH3). Sequences are listed in Table 2. Sequences are listed in Table 2. Real-time PCR reactions were prepared and performed on a Biorad iQ5 as previously described (Blankenship et al. 2010).

Table 2.

Strains used in the this study

| DAY185 |

ura3Δ::λimm434 ARG4::URA3::arg4::hisG HIS1::his1::hisG ura3Δ::λimm434 arg4::hisG his1::hisG |

(Davis et al., 2002) |

| NYY100 |

ura3Δ::λimm434 arg4::hisG his1::hisG::pHIS-SUN41-V5-DAmP sun41::ARG4 ura3Δ::λimm434 arg4::hisG his1::hisG sun41::URA3 |

This study |

| CTN41 |

ura3Δ::λimm434 arg4::hisG his1::hisG sun41::ARG4 ura3Δ::λimm434 arg4::hisG his1::hisG sun41::URA3 |

(Norice et al., 2007) |

| CTN46 |

ura3Δ::λimm434 arg4::hisG his1::hisG::pHIS1 sun41::ARG4 ura3Δ::λimm434 arg4::hisG his1::hisG sun41::URA3 |

(Norice et al., 2007) |

| NYY105 |

ura3Δ::λimm434 arg4::hisG his1::hisG::pHIS-SUN41-V5 sun41::ARG4 ura3Δ::λimm434 arg4::hisG his1::hisG sun41::URA3 |

This study |

2.4 Cell wall sensitivity assays

Strains were tested for drug sensitivity as previously described (Bruno et al., 2006). Single colonies were inoculated in YPD and grown overnight at 30°C. Cultures were diluted to an OD600 of3 and serially diluted five-fold to an OD600 of 0.6, 0.12, 0.024, 4.8 × 10−3, 9.6 × 10−4, or 1.9 × 10−4. Cells were spotted onto YPD, and YPD plus 200 μg/ml Congo red and incubated at 30°C for 48 hours.

2.5 Hyphal growth assays

Strains were grown overnight in YPD liquid medium. The strains were then diluted to an OD600 of 0.08 in spider medium at 37°C. The cultures were then incubated at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm for 4 hours, washed with PBS, and incubated for ten minutes in PBS + 0.1 mg/ml calcoflour white (Sigma) (Watanabe et al., 2005). Samples were visualized using a Zeiss Axio Observer Z.1 microscope and a 63x objective and acquired on a Coolsnap HQ2 (Photometrics) camera using Axiovision (Zeiss) software. ImageJ was used to process images (Abramoff, 2004).

2.6 In vitro biofilm assays

Biofilms were assayed as previously described (Nobile and Mitchell, 2005). Briefly, single colonies were grown overnight in YPD at 30°C. 12-well plates containing siliconesquare substrates pretreated with fetal bovine serum were inoculated with cultures diluted to OD600 of 0.5 in 2 ml of Spider medium (1% nutrient broth, 1% D-mannitol, 0.2% K2HPO4). The samples were incubated for 90 min at 35-rpm agitation at 37°Cfor adhesion to occur. The squares were then washed with 2 mlof phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove any unadhered cells and transferred to 2 ml of fresh Spider medium. The plates were then incubated for 48 hours at 35-rpm agitation at 37°C. After 48 hours the plates were photographed and analyzed for biofilm growth.

2.7 Biofilm dry mass calculations

Measurements of biofilm dry masses were performed in triplicate on biofilms grown in standard conditions for 48 hrs. Three silicone squares were gently removed to maintain all of the biofilm attached to the squares, vortexed and collected under suction on pre-weighed 0.45 μm nitrocellulose filters (Millipore). Filters were dried for four days and weighed. Final biomass was determined by subtracting the mass of the nitrocellulose filters from the total mass of the filter and cells.

2.8 In vivo biofilm model

In vivo biofilms were assayed by a rat central-venous-catheter infection model, as previously described (Andes et al., 2004). Catheters were removed from rats after 24 hours of C. albicans infection. The distal 2 cm of catheter material was assayed for biofilm growth and imaged using SEM at 50x and 100X magnification as described previously (Nett et al., 2007).

2.9 Protein extraction and Western blot analysis

Strains were grown overnight and diluted to an OD600 0.2 in YPD and grown to an OD600 ~1.0 at 30°C with 220-rpm agitation. Protein extraction was performed on the supernatants of the samples as previously (Brodsky and Schekman, 1993) with minor modification. Briefly, 1/10th volume of 0.3% deoxycholate, and 1/10th volume of 100% TCA were added to the supernatants. After 30 minutes on ice the samples were pelleted, washed two times with cold equilibrated acetone and dried for 30 minutes. The pellets were dissolved in SDS sample buffer overnight on ice. The samples were boiled for 5 minutes, pelleted and the supernatants were transferred to a new tube.

Gel electrophoresis and western blotting was done as previously described (Laemmli, 1970; Towbin et al., 1979) with minor modifications. The samples were boiled for 2 minutes and then loaded on precast gradient SDS polyacrylamide gel (BioRad). Following transfer to nitrocellulose the blot was inoculated with 1:2000 Anti-V5 primary antibody (Invitrogen) overnight, followed by a 1:5000 HRP-conjugated Goat Anti-Mouse secondary antibody (Invitrogen) for 1 hour. The HRP signal was developed using Supersignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo) and visualized with a Fulifilm LAS-3000 image Reader.

3.0 Results

3.1 Construction of a SUN41 DAmP strain

We chose to test DAmP strain utility in C. albicans with the SUN41 gene. Sun41 is a surface and secreted protein that is required for several biological processes, such as cell wall integrity and biofilm formation (Firon et al., 2007; Hiller et al., 2007; Norice et al., 2007). We anticipated that a partial defect in Sun41 function, caused by reduced expression, may cause a spectrum of phenotypes that are distinguishable from both wild-type and null mutant phenotypes. In other words, there is a better chance of detecting intermediate activity of an allele if there are several phenotypes to assay rather than just one.

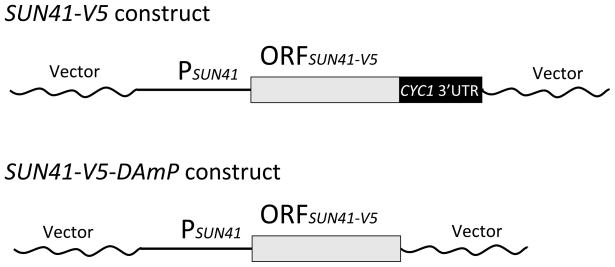

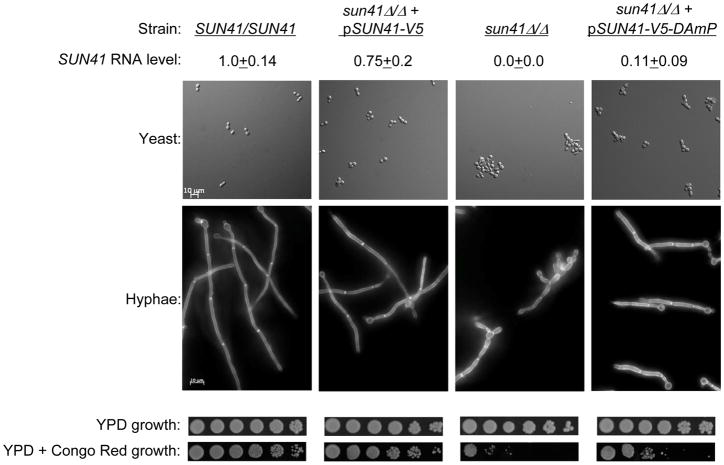

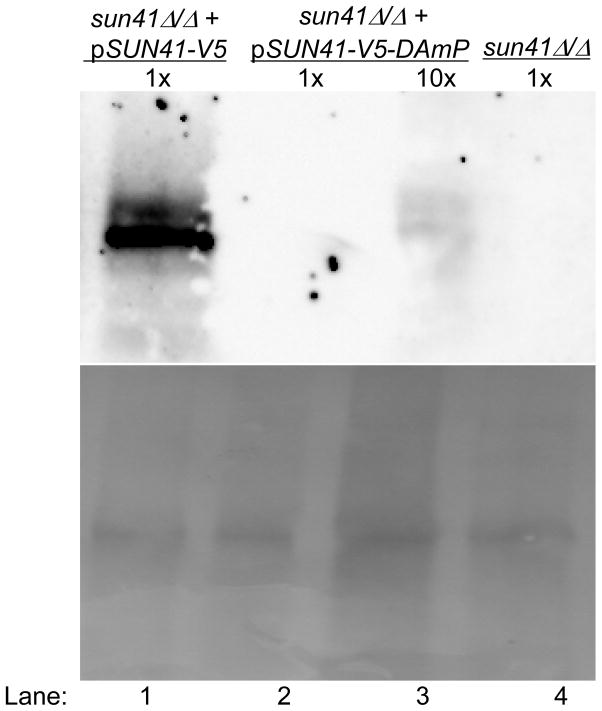

The DAmP allele of SUN41 was based on a functional complementing construct that also specified a C-terminal V5 epitope tag and included the 3′ untranslated region of the S. cerevisiae CYC1 gene (Figure 1). The DAmP construct included the SUN41-V5 coding region, but lacked CYC1 sequences (Figure 1), so that the 3′ end of the transcript would include vector sequences. For expression and functional assays, the SUN41-V5 and SUN41-V5-DAmP constructs were integrated at the HIS1 locus in a sun41Δ/Δ strain, and were compared to the sun41Δ/Δ strain carrying the vector alone integrated at HIS1. Quantitative RT-PCR assays indicated that SUN41 RNA accumulation was reduced approximately 7-fold in the sun41Δ/Δ + pSUN41-V5-DAmP strain compared to the sun41Δ/Δ + pSUN41-V5 complemented strain, or approximately 10-fold compared to the wild-type SUN41/SUN41 strain (Figure 2). A western blot indicated that the Sun41 protein accumulation was reduced more than 10-fold in the sun41Δ/Δ + pSUN41-V5-DAmP strain (Figure 3, lanes 2 and 3) compared to the sun41Δ/Δ + pSUN41-V5 complemented strain (Figure 3, lane 1). These results indicate that the DAmP allele reduces, but does not abolish SUN41 expression.

Figure 1. SUN41-V5 and SUN41-V5-DAmP alleles.

Complementing and DAmP constructs were created in vector pDDB78 (Spreghini et al., 2003). Each epitope-tagged coding region (ORFSUN41-V5) ends with a stop codon, followed by the 3′ untranslated region from the S. cerevisiae CYC1 gene (SUN41-V5) or vector sequences (SUN41-V5-DAmP). The coding regions are preceded by the SUN41 promoter and 5′ sequences (PSUN41). Vector sequences are bacterial in origin and derive from the plasmid vector. These 3′ sequences are detailed in the Methods section.

Figure 2. Phenotypic analysis of the SUN41 DAmP strain.

Strains indicated at the top of each column include SUN41/SUN41 (DAY185), sun41Δ/Δ + pSUN41-V5 (NYY105), sun41/(CTN46), and sun41Δ/Δ + pSUN41-V5-DAmP (NNY100). Levels of SUN41 RNA in each strain were determined by QRTPCR from YPD cultures, and are expressed as the ratio to control TDH3 RNA, then normalized to the wild type strain ratio. Yeast were visualized after 8 hr growth to mid-exponential phase in YPD at 30°C. Hyphae were visualized after 90 min growth in Spider medium at 37°C; samples were prepared by washing with PBS and staining for 10 minutes with 0.1 mg/ml of calcofluor white (Watanabe et al., 2005). Growth was compared on YPD and YPD + 200 μg/ml Congo Red after 48 hours at 30°C; overnight cultures were serially diluted five-fold from left to right.

Figure 3. Assay of Sun41 protein accumulation.

Strains were grown in YPD to logarithmic phase and supernatant proteins were fractionated by SDS PAGE. Sun41 protein was detected with anti-V5 (upper panel); total protein was detected with Ponceau S (lower panel). Strains are indicated at the top of each lane, including sun41Δ/Δ + pSUN41-V5-DAmP (NNY100; lane 1), sun41Δ/Δ + pSUN41-V5 (NYY105; lanes 2, 3), and sun41/(CTN46; lane 4). Lane 3 was loaded with 10-fold more supernatant than the other lanes. We estimated the size of Sun41-V5 at 50 kDa by comparison with protein size standards.

3.2 Phenotypic analysis of the SUN41 DAmP strain

Strains lacking SUN41 have defects in numerous cell wall-related processes. These processes include sensitivity to cell wall inhibitors, cell aggregation, hyphal morphogenesis, and biofilm formation in vitro (Firon et al., 2007; Hiller et al., 2007; Norice et al., 2007). Microscopic examination of the sun41Δ/Δ + pSUN41-V5-DAmP strain indicated that the SUN41-V5-DAmP construct retained some function. Aggregation of yeast-form cells at 30° was substantially reduced in the sun41Δ/Δ + pSUN41-V5-DAmP strain compared to the sun41Δ/Δ mutant strain (Figure 2). In addition, hyphae produced at 37° by the sun41Δ/Δ + pSUN41-V5-DAmP strain had more parallel walls and a more regular structure than those of the sun41Δ/Δ mutant (Figure 2). These observations suggest that the SUN41-V5-DAmP allele retains at least partial functional activity.

Assays for sensitivity to the cell wall inhibitor Congo Red revealed that the DAmP allele was not fully functional. We confirmed that the sun41Δ/Δ mutant strain was hypersensitive compared to the wild-type and sun41Δ/Δ + pSUN41-V5 complemented strains (Figure 2). However, the sun41Δ/Δ + pSUN41-V5-DAmP strain displayed sensitivity that was intermediate between the mutant and complemented strain. These results indicate that the SUN41-V5-DAmP allele is not fully functional.

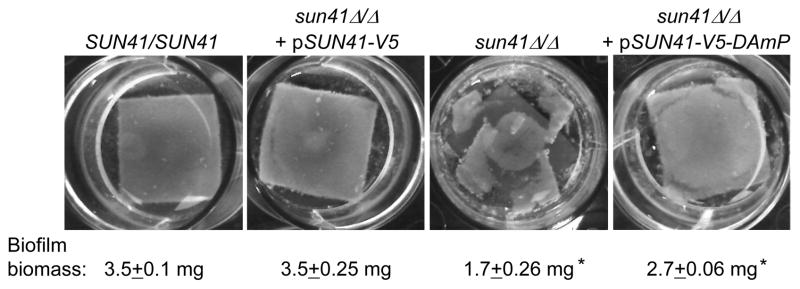

Mutants lacking Sun41 are defective in biofilm formation in vitro (Firon et al., 2007; Hiller et al., 2007; Norice et al., 2007). Control assays confirmed that our sun41Δ/Δ strain was biofilm-defective, while the wild-type and complemented strains were biofilm-competent (Figure 4). The sun41Δ/Δ + pSUN41-V5-DAmP strain appeared biofilm-competent (Figure 4). Quantitation of biofilm biomass revealed that the DAmP strain had a slight biofilm defect, so that its phenotype was intermediate between the mutant and complemented strains. These results indicate that substantial biofilm formation proceeds despite a reduction in Sun41 protein levels, but supports the conclusion that the SUN41-V5-DAmP allele is not fully functional.

Figure 4. Biofilm formation in vitro.

Biofilm formation in vitro was photographed and measured after 48 hrs for the strains indicated in the Figure 2 legend. Biofilm biomass assays were performed in triplicate. Asterisks indicate measurements that are significantly different from the reference SUN41/SUN41 strain. Statistical significance (p-values) was calculated with a two-tailed t-test function in Microsoft Excel.

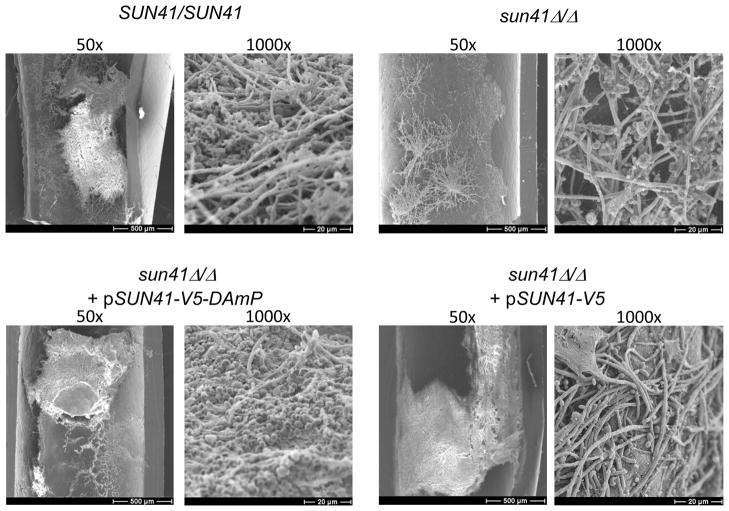

To more clearly define the relevance of these observations to infection, we tested biofilm formation in vivo in a rat catheter infection model (Andes et al., 2004). The wild-type and complemented strains produced substantial biofilms in vivo, as visualized with scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Figure 5). The sun41Δ/Δ mutant strain produced sparse growth in the catheter, forming what appeared to be small colonies with long emanating hyphae (Figure 5). The DAmP strain produced a substantial biofilm in vivo that included both yeast cells and hyphae (Figure 5). The 50x images show the differences in biofilm formation ability among the strains most clearly. The 1000x images show that what growth occurs is fairly normal in appearance, even for the sun41Δ/Δ mutant. These results indicate that Sun41 is required for biofilm formation in vivo in this model, and that the DAmP allele produces sufficient product to support biofilm formation in vivo.

Figure 5. Biofilm formation in vivo.

Biofilm formation in vivo was assayed at 24 hrs for the strains indicated in the Figure 2 legend. Catheter lumen surfaces were imaged via scanning electron microscopy at 1000x or 50x magnification as indicated.

4. Discussion

Loss of Sun41 leads to a constellation of phenotypes (Firon et al., 2007; Hiller et al., 2007; Norice et al., 2007). We report here that a SUN41 DAmP strain displays partial phenotypic defects compared to a sun41Δ/Δ strain. Notably, for SUN41, there is no gene dosage effect that distinguishes the wild-type strain, with two alleles, and the complemented strain, with one allele. Thus the SUN41 DAmP strain provides a unique opportunity to examine the consequences of limiting Sun41 activity.

Our studies here illustrate one useful application of DAmP strains: to evaluate a possible therapeutic target. Sun41 is a good candidate target because it is a surface and secreted protein, hence accessible to external inhibitors. In addition, as we report here, Sun41 is required for biofilm formation in vivo in a catheter infection model, so in principle it could be targeted to eliminate a major source of disseminated infection. However, the SUN41 DAmP strain produces a considerable biofilm in vivo. Therefore, an inhibitor would have to be extremely active to reduce Sun41 function below the threshold required for catheter biofilm formation. It would make sense to test other candidate targets through analysis of DAmP strains or other approaches to permit informed prioritization.

One great value of DAmP alleles is to enable systematic functional analysis of essential genes in C. albicans. The goal is not simply to determine whether a gene is essential or not, but to define its functional role. Existing approaches include acute shut-off experiments using fusions to regulated promoters (Backen et al., 2000; Care et al., 1999; Nakayama et al., 2000; Park and Morschhauser, 2005; Roemer et al., 2003) and analysis of heterozygous deletion strains (Oh et al.; Roemer et al., 2003; Uhl et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2005). On a case-by-case basis, one can also use characterized mutations in orthologous genes as a model to create temperature-conditional alleles (Devasahayam et al., 2002; Fang and Wang, 2006; Kennedy et al., 2000), or use characterized chemical inhibitors (Bastidas et al., 2009; Cowen and Lindquist, 2005; Zacchi et al., 2010). No single approach is perfect for all genes; there is no “one size fits all” in Genetics! Hence we expect that DAmP strains, which have proven extremely useful in S. cerevisiae (Yan et al., 2008), will also prove useful in C. albicans.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank lab members for their advice and discussions. We thank Dr. Carmelle T. Norice for construction of plasmid pCTNB4.

Role of Funding: Our work was funded by NIH Grant R01 AI067703 (APM) and NIH postdoctoral fellowship F32 AIO85521 (JSF). The funding institutes played no role in the design, or implementation of experiments described here.

Contributor Information

JS Finkel, Email: jsfinkel@andrew.cmu.edu.

N Yudanin, Email: nyudanin@gmail.com.

JE Nett, Email: jenett@medicine.wisc.edu.

DR Andes, Email: dra@medicine.wisc.edu.

References

- Abramoff MD, Magelhaes PJ, Ram SJ. Image Processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics International. 2004;11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Alby K, et al. Homothallic and heterothallic mating in the opportunistic pathogen Candida albicans. Nature. 2009;460:890–3. doi: 10.1038/nature08252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andes D, et al. Development and characterization of an in vivo central venous catheter Candida albicans biofilm model. Infect Immun. 2004;72:6023–31. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.6023-6031.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backen AC, et al. Evaluation of the CaMAL2 promoter for regulated expression of genes in Candida albicans. Yeast. 2000;16:1121–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(20000915)16:12<1121::AID-YEA614>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastidas RJ, et al. The protein kinase Tor1 regulates adhesin gene expression in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000294. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship JR, et al. An extensive circuitry for cell wall regulation in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000752. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky JL, Schekman R. A Sec63p-BiP complex from yeast is required for protein translocation in a reconstituted proteoliposome. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:1355–63. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.6.1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno VM, et al. Control of the C. albicans cell wall damage response by transcriptional regulator Cas5. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e21. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Care RS, et al. The MET3 promoter: a new tool for Candida albicans molecular genetics. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:792–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowen LE, Lindquist S. Hsp90 potentiates the rapid evolution of new traits: drug resistance in diverse fungi. Science. 2005;309:2185–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1118370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis DA, et al. Candida albicans Mds3p, a conserved regulator of pH responses and virulence identified through insertional mutagenesis. Genetics. 2002;162:1573–81. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.4.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devasahayam G, et al. The Ess1 prolyl isomerase is required for growth and morphogenetic switching in Candida albicans. Genetics. 2002;160:37–48. doi: 10.1093/genetics/160.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epp E, et al. Forward genetics in Candida albicans that reveals the Arp2/3 complex is required for hyphal formation, but not endocytosis. Mol Microbiol. 2010;75:1182–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.07038.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang HM, Wang Y. RA domain-mediated interaction of Cdc35 with Ras1 is essential for increasing cellular cAMP level for Candida albicans hyphal development. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61:484–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firon A, et al. The SUN41 and SUN42 genes are essential for cell separation in Candida albicans. Mol Microbiol. 2007;66:1256–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, et al. Gene overexpression/suppression analysis of candidate virulence factors of Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:483–92. doi: 10.1128/EC.00445-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiller E, et al. Candida albicans Sun41p, a putative glycosidase, is involved in morphogenesis, cell wall biogenesis, and biofilm formation. Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6:2056–65. doi: 10.1128/EC.00285-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homann OR, et al. A phenotypic profile of the Candida albicans regulatory network. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy MA, et al. Cloning and sequencing of the Candida albicans C-4 sterol methyl oxidase gene (ERG25) and expression of an ERG25 conditional lethal mutation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Lipids. 2000;35:257–62. doi: 10.1007/s11745-000-0521-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–5. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhlrad D, Parker R. Aberrant mRNAs with extended 3′ UTRs are substrates for rapid degradation by mRNA surveillance. RNA. 1999;5:1299–307. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299990829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama H, et al. Tetracycline-regulatable system to tightly control gene expression in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6712–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.12.6712-6719.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nett J, et al. Putative role of beta-1,3 glucans in Candida albicans biofilm resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:510–20. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01056-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobile CJ, Mitchell AP. Regulation of cell-surface genes and biofilm formation by the C. albicans transcription factor Bcr1p. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1150–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norice CT. Thesis (PhD) Columbia University; New York: 2008. Studies of Candida albicans Sun41 function and regulation. [Google Scholar]

- Norice CT, et al. Requirement for Candida albicans Sun41 in biofilm formation and virulence. Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6:2046–55. doi: 10.1128/EC.00314-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J, et al. Gene annotation and drug target discovery in Candida albicans with a tagged transposon mutant collection. PLoS Pathog. 6 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YN, Morschhauser J. Tetracycline-inducible gene expression and gene deletion in Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4:1328–42. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.8.1328-1342.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: a persistent public health problem. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:133–63. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00029-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rex JH, et al. Practice guidelines for the treatment of candidiasis. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:662–78. doi: 10.1086/313749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roemer T, et al. Large-scale essential gene identification in Candida albicans and applications to antifungal drug discovery. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:167–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soll DR, et al. Relationship between switching and mating in Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell. 2003;2:390–7. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.3.390-397.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreghini E, et al. Roles of Candida albicans Dfg5p and Dcw1p cell surface proteins in growth and hypha formation. Eukaryot Cell. 2003;2:746–55. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.4.746-755.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H, et al. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:4350–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhl MA, et al. Haploinsufficiency-based large-scale forward genetic analysis of filamentous growth in the diploid human fungal pathogen C. albicans. EMBO J. 2003;22:2668–78. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H, et al. Analysis of chitin at the hyphal tip of Candida albicans using calcofluor white. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2005;69:1798–801. doi: 10.1271/bbb.69.1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D, et al. Genome-wide fitness test and mechanism-of-action studies of inhibitory compounds in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e92. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z, et al. Yeast Barcoders: a chemogenomic application of a universal donor-strain collection carrying bar-code identifiers. Nat Methods. 2008;5:719–25. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacchi LF, et al. Mds3 regulates morphogenesis in Candida albicans through the TOR pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:3695–710. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01540-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, et al. Analysis of the Candida albicans Als2p and Als4p adhesins suggests the potential for compensatory function within the Als family. Microbiology. 2005;151:1619–30. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27763-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]