Abstract

Background

The objectives of this study were to examine the magnitude of, and 20-year trends in, age differences in short-term outcomes among men and women hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in central Massachusetts.

Methods

The study population consisted of 5,907 male and 4,406 female residents of the Worcester, MA, metropolitan area hospitalized at all greater Worcester medical centers with AMI between 1986 and 2005.

Results

Overall, among both men and women, older patients were significantly more likely to have developed atrial fibrillation, heart failure, and to have died during hospitalization and within 30 days after admission compared to patients <65 years. Among men, age differences in the risk of developing atrial fibrillation have widened over the past 2 decades, while differences in the risk of developing cardiogenic shock have narrowed for men 75 years and older as compared with those <65 years. Among women, age differences in the risk of developing these major complications of AMI have not changed significantly over time. Age differences in short-term mortality have remained relatively unchanged over the past 20 years in both sexes, though individuals of all ages have experienced declines in short-term death rates over this period.

Conclusions

Elderly men and women are more likely to experience adverse short-term outcomes after AMI and age differences in short-term mortality rates have remained relatively unchanged in both sexes over the past 20 years. More targeted treatment approaches during hospitalization for AMI and thereafter are needed for older patients to improve their prognosis. Word count: 248

Keywords: Acute myocardial infarction, hospital complications, hospital mortality, age and sex differences

Introduction

Over the past several decades, dramatic advances in the medical management of patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) have been accompanied by reductions in in-hospital clinical complications and short-term death rates.1,2 Despite encouraging declines in population death rates from coronary heart disease (CHD) and hospital mortality from AMI in the U.S. since the late 1960s,3 several groups, including older individuals, women, and patients with multiple comorbidities remain at increased risk for adverse outcomes after hospitalization for AMI.

Previous studies examining age and sex differences in the development of hospital complications and risk of dying in the setting of AMI have shown inconsistent results.4–9 While some studies found that older persons had higher hospital complication and mortality rates compared with younger individuals,3–6,10,11 other studies have not.7–9,12 Despite national interest, few studies have examined age-specific differences in important in-hospital complications and short-term death rates separately for men and for women. Further, there is a lack of data from a broad community-wide perspective that has examined changing, and contemporary, associations between age and short-term outcomes in men and women hospitalized with AMI.3,13

The objectives of this study were to examine relatively contemporary age differences, and 20-year trends (1986–2005) therein, in the development of important in-hospital clinical complications and short-term death rates among residents of central Massachusetts hospitalized with AMI, separately for men and women. Data from the population-based Worcester Heart Attack Study were used for this investigation.14–16

Methods

The Worcester Heart Attack Study is an ongoing clinical/epidemiologic investigation that is examining long-term trends in the incidence, hospital, and post-discharge case-fatality rates of AMI among residents of the Worcester metropolitan area hospitalized at all 16 greater Worcester medical centers in 15 biennial periods between 1975 and 2005.14–16 Fewer hospitals (n = 11) have been included during recent study years due to hospital closures, mergers, and conversion to chronic care facilities. In brief, computerized printouts of patients discharged from all greater Worcester hospitals with possible AMI were obtained and several International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes in which cases of AMI may have been diagnosed were reviewed. Cases of possible AMI were independently validated according to predefined criteria for AMI which included a suggestive clinical history, serum enzyme elevations, and serial electrocardiographic findings during hospitalization consistent with the presence of AMI; at least 2 of these 3 criteria needed to be present for an AMI to have occurred. Patients with an initial AMI (incident event), as well as those with a prior history of AMI, based on the review of information contained in hospital medical records, were included in our study population. Residents of the Worcester metropolitan area who satisfied these criteria were included in the present investigation.

Data Collection

The hospital medical records of greater Worcester residents with confirmed AMI were reviewed by trained study physicians and nurses who abstracted information about patient’s demographic characteristics, medical history, clinical presentation, hospital treatment approaches, and hospital discharge status. Age was categorized into 3 strata of <65 years, 65–74 years, and ≥75 years. The principal study outcomes included the development of important in-hospital clinical complications and total hospital and 30 day mortality. Atrial fibrillation (AF) included the documentation of new onset AF in the hospital medical record or occurrence of typical electrocardiographic changes consistent with this diagnosis.17 Heart failure was indicated by clinical or radiographic evidence of pulmonary edema or bilateral basilar rales with an S3 gallop18 while cardiogenic shock was defined according to previously described criteria.19 Since the average length of stay for patients hospitalized with AMI has declined during the years under study,20 we also examined 30-day post-admission death rates as a secondary study outcome. All patients discharged from greater Worcester hospitals after AMI were followed through a search of death certificates to determine their vital status.

Data Analysis

All analyses were performed separately for men and for women. Differences in baseline demographic, clinical characteristics, and hospital therapies in relation to patient age were compared using the chi-square test for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables.

Using logistic regression models, we estimated odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for the association between age and various hospital outcomes. Patients with prevalent disease, namely those who had the condition being examined previously diagnosed based on the review of information contained in hospital medical records since patients were never directly contacted as part of this study, were excluded from models examining the development of incident (initial events) cases of several hospital clinical complications (508 men and 471 women with prior AF, and 950 men and 1,155 women with prior heart failure). Potential confounding factors included in our regression models were selected on the basis of the findings from prior studies and on their clinical importance; these variables included race, marital status, comorbidities, AMI order (initial (incident) vs. prior (recurrent) event), type (Q wave vs. non–Q wave), duration of pre-hospital delay following the onset of acute coronary symptoms, and length of hospital stay. Because information on body mass index was not collected until 1995, and information on acute symptoms and whether the AMI was a non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) or an ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) was not recorded until 1997, these variables were not included in our regression models. Study year was grouped into 5 two-year periods (1986/1988, 1990/1993, 1995/1997, 1999/2001, and 2003/2005) for ease of analysis. In all regression models, patients <65 years served as the reference category. Interaction terms between age and study period were used to examine whether age differences in the principal study outcomes changed significantly over time. Likelihood ratio tests were used to compare models with and without interaction terms. For 30-day death rates after hospital admission, similar multivariable adjusted Cox proportional hazard models yielded estimated hazards ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Massachusetts Medical School approved this study.

Results

Patient Characteristics

The study sample consisted of 10,313 residents of the Worcester metropolitan area (5,907 men and 4,406 women) hospitalized with validated AMI at all greater Worcester medical centers in 11 study years between 1986 and 2005. Overall, women were considerably older, on average, than men (75 years vs. 66 years). While 43% of men were aged <65 years, only 19% of women were in this age category; in contrast, 56% of women were 75 years and older compared with 31% of hospitalized men; relatively similar differences between the sexes according to age were observed in analyzing data from patients hospitalized in the 2 most recent periods under study (2003/2005).

During the past 20 years, among both men and women, age was strongly associated with several demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 1). In men and in women, the proportion of patients with a history of AF, heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, and stroke was higher in older patients. The proportion of patients with an initial, Q-wave MI, and STEMI was lower in older patients in both sexes. Heart rate, serum glucose, and creatinine levels were higher, on average, in older patients in both sexes; diastolic blood pressure, serum levels of total and LDL cholesterol, and patient’s body mass index were, however, lower in older women and men (Table 1). A relatively similar distribution of patient characteristics, stratified according to age, was observed when we examined these characteristics among patients included in the 2 most recent cohorts (2003/2005).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients Hospitalized with Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI) According to Age and Sex (1986–2005)

| Men |

Women |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | <65 y (n=2,554) |

65–74y (n=1,545) |

≥75y ( n=1,808) |

P- value |

<65y (n=855) |

65–74y (n=1,092) |

≥75y (n=2,459) |

P- value |

| Age (mean ± SD, years) | 53.4 (±8.0) | 69.7 (±2.9) | 81.8 (±5.1) | 55.2 (±7.6) | 70.0 (±2.8) | 83.3 (±5.7) | ||

| White (%) | 91.9 | 95.0 | 97.6 | <0.001 | 90.0 | 93.2 | 96.4 | <0.001 |

| Marital status (%) | ||||||||

| Single | 14.3 | 9.6 | 7.2 | <0.001 | 11.4 | 10.4 | 10.6 | <0.001 |

| Married | 73.8 | 76.9 | 67.3 | 60.1 | 45.3 | 26.0 | ||

| Divorced | 9.6 | 5.9 | 3.1 | 14.3 | 7.4 | 2.8 | ||

| Widowed | 2.2 | 7.5 | 22.5 | 11.5 | 37.0 | 60.6 | ||

| Medical History (%) | ||||||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 2.7 | 11.2 | 19.7 | <0.001 | 2.4 | 8.8 | 17.5 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 48.0 | 59.4 | 64.3 | <0.001 | 56.0 | 69.9 | 72.8 | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 6.2 | 17.2 | 29.0 | <0.001 | 13.0 | 21.0 | 33.1 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 20.9 | 33.4 | 31.0 | <0.001 | 35.8 | 39.8 | 30.0 | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 4.2 | 11.7 | 16.8 | <0.001 | 6.7 | 10.7 | 13.7 | <0.001 |

| AMI characteristics (%) | ||||||||

| Initial | 72.7 | 59.6 | 58.1 | <0.001 | 73.0 | 66.9 | 62.3 | <0.001 |

| Q-wave | 46.1 | 35.9 | 22.8 | <0.001 | 37.2 | 31.5 | 27.1 | <0.001 |

| STEMI* | 53.1 | 43.0 | 26.9 | <0.001 | 47.0 | 34.6 | 30.7 | <0.001 |

| Pre-hospital delay (hours)*, | ||||||||

| median (IQR) | 1.9(1.0– 4.2) | 2.0(1– 4.5) | 2.5(1.2–5.1) | <0.001 | 2.0(1.0–4.7) | 2.4(1.3–5.5) | 2.3(1.2–5.0) | 0.05 |

| Clinical parameters on admission, median (IQR) | ||||||||

| Heart rate(beats/min) | 80(67–94) | 81( 67–100) | 87(71–102) | <0.001 | 83(70–99) | 84(72–102) | 88(74–105) | <0.001 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 141(122–162) | 142(121–160) | 140(117–160) | 0.05 | 142(121–164) | 143(120–170) | 141(120–165) | 0.83 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 84(70–98) | 80(67–91) | 73(61–86) | <0.001 | 80(64–92) | 77(64–90) | 70(57.5–86) | <0.001 |

| BMI(kg/m2)* | 28.6(25.7–32.3) | 27.3(24.4–30.3) | 25.6(23.1–28.0) | <0.001 | 28.1(24.5–33.1) | 27.3(23.0–32.1) | 24.6(21.3–28.3) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory findings on admission, median (IQR) | ||||||||

| Cholesterol(mg/dl) | 210(171–236) | 186(158–223) | 172(142–205) | <0.001 | 209(174–247) | 215(174–251) | 199(91–235) | <0.001 |

| LDL(mg/dl) | 115(94–142) | 105(82–124) | 97(75–121) | <0.001 | 111(87–142) | 107(84–141) | 102(78–133) | <0.004 |

| Glucose(mg/dl) | 134(112–178) | 151(119–209) | 150(120–209) | <0.001 | 146(116–238) | 163(125–247) | 161(126–228) | 0.02 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.1(0.9–1.2) | 1.2(1.0–1.5) | 1.4(1.1–1.9) | <0.001 | 0.9(0.8–1.2) | 1.0(0.9–1.3) | 1.2(0.9–1.6) | <0.001 |

| Length of stay (days), | ||||||||

| median (IQR) | 6(3–9) | 7(4–10.5) | 6(4–10) | <0.001 | 6(4–10) | 7(4–11) | 6(4–10) | <0.001 |

IQR: Inter quartile range; LDL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol;

Information on pre-hospital delay, body mass index (BMI), acute presenting symptoms, and STEMI was recorded beginning in 1991, 1995, and 1997, respectively.

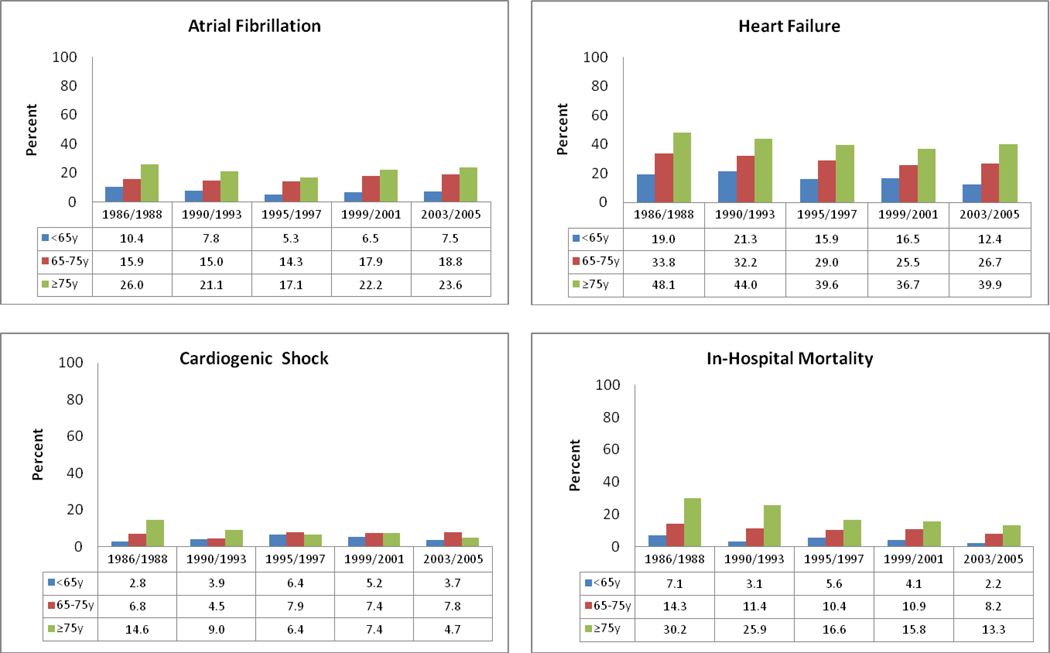

Age Differences in Hospital Clinical Complications and Death Rates, and Trends over Time, among Men

Between 1986/1988 and 2003/2005, the likelihood of developing AF increased slightly in men aged 65–74 years (16% vs. 19%), whereas the odds of developing AF decreased slightly in younger (10% vs. 8%) and older men (26% vs. 24%) (Figure 1) (p <05). On the other hand, the incidence rates of new onset heart failure declined significantly over time in all age groups (19% vs. 12% for men<65 years; 34% vs. 27% for men 65–74 years; 48% vs. 40% for men ≥ 75 years) (p<05). The frequency of cardiogenic shock decreased over time in men ≥75 years (15% vs. 5%) (p<05), but did not significantly change among younger patients. Declining in-hospital death rates were observed for men of all ages over the past two decades: ≥75 years (30% in 1986/88 vs. 13% in 2003/05), 65–74 years (14% vs. 8%); and <65 years (7% vs. 2%) (p<05) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Clinical Complications and In-Hospital Mortality According to Age and Study Period Among Men

The significant interaction between age and study period (p = .04) indicated that age differences in the risk of developing AF have changed significantly over time (Table 2); in 1986/1988, the adjusted ORs for AF were 1.61 and 2.83 for men 65–74 years and men ≥75 years, respectively; in 2003/2005 these multivariable adjusted ORs were 3.73, and 4.60, respectively, compared with men <65 years. In examining 20 year trends in the risk of developing cardiogenic shock, the significant interaction between age and study period (p = .02) suggest that age differences in the risk of developing this clinical complication have changed significantly over time (Table 2); in 1986/1988, the adjusted ORs for cardiogenic shock were 0.75 and 2.19 for men 65–74 years and men ≥75 years, respectively; in 2003/2005 these ORs were 1.86, and 1.10, respectively, compared with men<65 years.

Table 2.

Age Differences in Clinical Complications and Short-term Mortality in Patients Hospitalized with Acute Myocardial Infarction

| Men |

Women |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <65 y | 65–74 y | ≥75 y | P value† |

<65 y | 65–74 y | ≥75 y | P value† |

|

| Atrial fibrillation | ||||||||

| Events, n (%) | 185(7.4) | 226(16.1) | 325(21.7) | 68(8.1) | 141(13.9) | 451(21.7) | ||

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Referent | NA* | NA | 0.12 | Referent | 1.79(1.31–2.42) | 3.17(2.42–4.15) | 0.60 |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Referent | NA | NA | 0.04 | Referent | 1.74(1.25–2.43) | 3.09(2.27–4.21) | 0.40 |

| Heart failure | ||||||||

| Events, n (%) | 414(17.3) | 381(29.8) | 526(41.0) | 169(22.7) | 299(34.7) | 715(43.5) | ||

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Referent | 2.00(1.71–2.35) | 3.41 (2.92–3.98) | 0.76 | Referent | 1.75(1.40–2.18) | 2.68(2.19–3.26) | 0.28 |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Referent | 1.68(1.38–2.05) | 2.88(2.36–3.52) | 0.23 | Referent | 1.61(1.22–2.11) | 2.26(1.75–2.92) | 0.24 |

| Cardiogenic shock | ||||||||

| Events, n (%) | 113(4.4) | 102(6.6) | 139(7.7) | 58(5.7) | 151(7.6) | 479(7.2) | ||

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Referent | NA | NA | <0.001 | Referent | 1.30(0.90–1.87) | 1.33(0.96–1.84) | 0.60 |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Referent | NA | NA | 0.02 | Referent | 1.28(0.82–1.99) | 1.38(0.91–2.10) | 0.42 |

| In-hospital mortality | ||||||||

| Events, n (%) | 108(4.2) | 171(11.1) | 345(19.1) | 58(6.8) | 151(13.8) | 479(19.5) | ||

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Referent | 2.77(2.15–3.56) | 5.76(4.59–7.23) | 0.15 | Referent | 2.11(1.54–2.90) | 3.49(2.62–4.65) | 0.41 |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Referent | 2.83(2.09–3.84) | 5.21(3.90–6.98) | 0.13 | Referent | 2.10(1.43–3.08) | 3.32(2.32–4.75) | 0.22 |

| 30-hospital mortality | ||||||||

| Events, n (%) | 129(5.1) | 213(13.8) | 427(23.8) | 64(7.5) | 166(15.2) | 590(24.1) | ||

| Crude HR (95% CI) | Referent | 2.94(2.33–3.71) | 5.78(4.68–7.14) | 0.91 | Referent | 1.95(1.44–2.66) | 3.74(2.85–4.92) | 0.80 |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | Referent | 2.90(2.19–3.85) | 5.10(3.90–6.66) | 0.80 | Referent | 1.91(1.33–2.76) | 3.44(2.46–4.80) | 0.42 |

Model adjusted for race, marital status, study period, medical history, AMI-associated characteristics, and length of stay.

p values for interaction terms between age and study period

NA: Not applicable. Among men, since age differences in AF and cardiogenic shock have changed significantly over time, adjusted ORs for each study period were calculated separately and are presented in the text; there were no overall ORs for these outcomes.

On the other hand, age differences in the risk of developing heart failure, and in-hospital and 30-day mortality, have not changed significantly over time (Table 2). Overall, older men were more likely to have developed heart failure during hospitalization than men <65 years. Similarly, older men of all ages were significantly more likely to have died during hospitalization and during the first 30 days after hospital admission compared with men <65 years (Table 2).

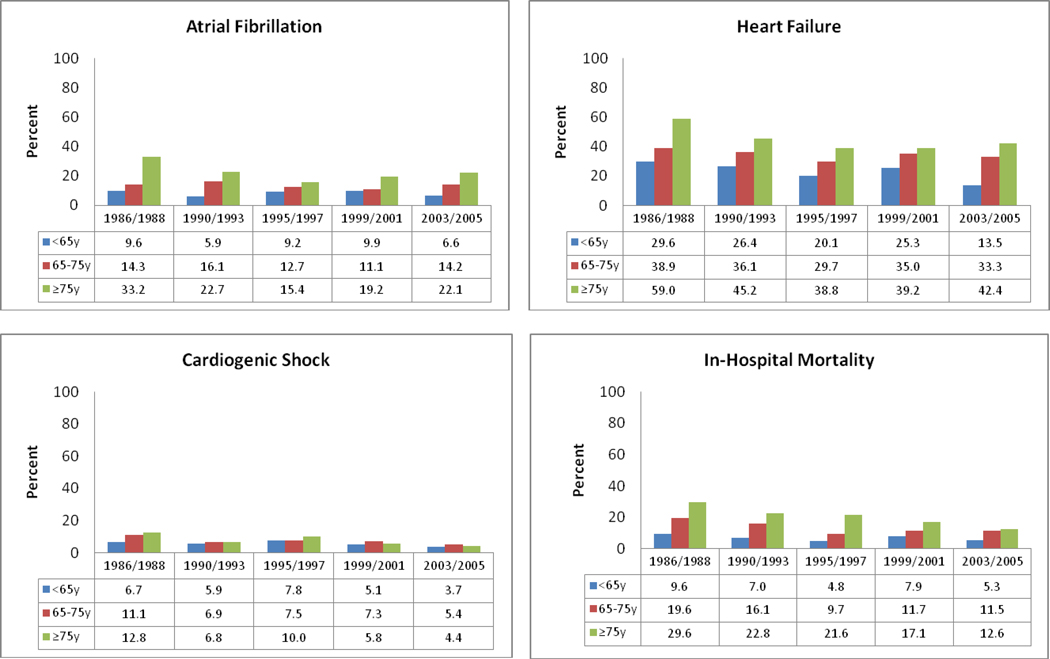

Age Differences in Hospital Clinical Complications and Death Rates, and Trends over Time, among Women

Between 1986/1988 and 2003/2005, the incidence rates of AF decreased in women <65 years (10% vs. 7%) and women ≥75 years (33% vs. 22%), but remained relatively unchanged in women 65–74 years (Figure 2). The incidence rates of new onset heart failure and cardiogenic shock decreased in all age groups over time (Figure 2). Declining in-hospital death rates were observed for women of all ages over the past two decades with the extent of decline ranging from 41% to 57% in the 3 age strata examined (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Clinical Complications and In-Hospital Mortality According to Age and Study Period Among Women

Age differences in hospital clinical complications and short-term mortality have not, however, changed significantly among women over the past 20 years (Table 2). Overall, older women were significantly more likely to have developed AF during hospitalization for AMI than women < 65 years (adjusted ORs were 1.74 and 3.09 for women 65–74 years and ≥75 years, respectively). Older women were significantly more likely to have developed heart failure after AMI compared with younger women (adjusted ORs were 1.61 and 2.26 for women 65–74 years and women ≥75 years, respectively). Compared with women <65 years, older women were more likely to have died during hospitalization as well as during the 30 days following hospital admission (Table 2).

Discussion

In this study of more than 10,000 residents of a large central New England metropolitan area hospitalized with AMI, older men and women were more likely to have developed AF and heart failure, and were more likely to have died during hospitalization and during the first 30-days after admission, compared with patients <65 years. Older men were also more likely to have developed cardiogenic shock compared with younger men. Among men, age differences in the risk of developing AF and cardiogenic shock have widened over time. Encouragingly, we noted a steady improvement in the majority of hospital outcomes examined in most age groups over the 20 year period under study, with a particularly marked improvement observed in the risk of developing cardiogenic shock in elderly but not in younger patients. While unknown, these latter findings may be due to the changing characteristics of patients hospitalized with AMI over time and/or to the more frequent use of cardiac catheterization and PCI in elderly patients.

Our results are consistent with the findings from previous studies which have shown that older patients hospitalized with AMI have a worse prognosis than younger patients.1,2,5,15 Older patients are more likely to have additional comorbidities present at the time of hospitalization for AMI which may increase their risk of developing clinically significant hospital complications and dying. Previous studies have shown that older patients are less likely to be treated with evidence-based cardiac medications and interventional procedures,4,21 which may have contributed to their greater risk of dying in the short-term. Other factors such as prolonged delay in seeking medical care,5,6 limited health care access, cognitive impairment, and frailty may also have played a role in the less favorable prognosis observed in older patients.

We found that age differences in the risk of developing new onset AF during hospitalization for AMI have widened during the past 20 years for men. On the other hand, differences in the risk of developing cardiogenic shock between men 65–74 years and men <65 years have widened over time but have narrowed for men ≥75 years. Our findings also showed that, despite the fact that the overall in-hospital death rates among patients with AMI have decreased from 17% in 1986/1988 to 9% in 2003/2005, age differences in short-term mortality have remained relatively unchanged over time among both men and women; the elderly remain at higher risk for dying than younger patients.

The present findings may be partially explained by the fact that while the use of effective treatment modalities have increased in all age groups over time,22,23 the prevalence of clinically significant comorbidities have increased over time3, especially in older patients. These latter trends make the management of hospitalized patients all the more challenging and increase the risk for adverse outcomes. Inasmuch, physicians need to consider the greater use of these treatment modalities in older patients to improve their short-term outcomes. Indeed, it is possible that the more aggressive management of elderly patients with coronary interventional procedures led to their declining risk of cardiogenic shock, and improving hospital survival, during the period under study. The enhanced use of these treatment regimens may also result in greater quality of life in patients of all ages and improvements in long-term prognosis.

We also observed that the short-term death rates were much higher in younger women than in younger men, with these differences persisting in the most recently hospitalized study cohorts; there were no sex differences in the crude short-term death rates among older patients. This finding is consistent with the results of previous studies.6,11,24–26

The reasons for worse short-term outcomes in younger women hospitalized with AMI are unclear but may be partially explained by the fact that women have a higher prevalence of comorbid conditions than men, and differences in these and other important prognostic factors are likely to be more pronounced in younger than in older individuals.25 In addition, younger women have been shown to be less likely to be treated with effective cardiac medications.13,26which can contribute to the worse outcomes noted in younger women. However, a previous study of patients enrolled in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction suggested that differences in medical history, clinical severity of the infarction, and early management accounted only for about one third of the differences in early mortality observed between men and women hospitalized with AMI.6 The fact that men may be more likely to die out-of-hospital from coronary disease than women, and that this sex difference may be larger in younger than in older individuals,25 could contribute to higher in-hospital death rates in younger women hospitalized with AMI. Additional prospective studies need to be carried out to understand the reasons behind the greater risk of adverse outcomes noted in younger women and older individuals hospitalized with acute coronary disease.

Study Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study include its population-based design that captured all validated cases of AMI occurring among residents of the Worcester metropolitan area hospitalized at all Central Massachusetts medical centers over a 20-year period. On the other hand, the study population was predominantly white and the generalizability of our findings to other race/ethnic groups may be limited. We did not have information available on several patient-associated characteristics (e.g., socioeconomic status, psychological factors) which may have confounded some of the observed associations. Because patients who died before hospitalization for AMI were not included, our findings are only generalizable to patients hospitalized with AMI.

In conclusion, while encouraging declines in hospital death rates and in the occurrence of several important clinical complications have declined in men and women of all ages during the past 20 years, older men and women were more likely to experience adverse short-term outcomes after hospitalization for AMI than patients <65 years. More targeted treatment approaches during hospitalization for AMI for older patients are needed to improve their short-term prognosis.

Acknowledgement

This research was made possible by the cooperation of participating hospitals in the Worcester metropolitan area and by our dedicated team of physician and nurse data abstractors.

Funding support: Funding for this project was provided by the National Institutes of Health grant RO1 HL35434. Partial salary support for Drs. Saczynski, Gore, Waring, and Goldberg was provided for by the National Institutes of Health grant 1U01HL105268-01.

Appendix. Characteristics of Patients Hospitalized with Acute Myocardial Infarction by Sex and by Age (2003/2005)

| Characteristics | Men |

Women |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <65 y (n = 466) |

65–74y (n = 244) |

≥75y (n = 408) |

p- value |

<65 y (n = 189) |

65–74y (n = 166) |

≥75y (n = 586) |

p- value |

|

| Age (mean ± SD, years) | 53.4 ( 7.83 ) | 69.9 ( 2.99 ) | 82.8 ( 5.19 ) | 55.4 ( 7.12 ) | 70.0 ( 2.68 ) | 84.3 ( 5.89 ) | ||

| White (%) | 86.6 | 83.3 | 92.6 | 0.001 | 95.1 | 94.6 | 98.4 | 0.005 |

| Marital status (%) | ||||||||

| Single | 19.7 | 11.6 | 7.6 | <0.001 | 16.4 | 13.3 | 11.1 | <0.001 |

| Married | 62.2 | 69.4 | 64.1 | 53.9 | 43.6 | 25.6 | ||

| Divorced | 16.1 | 10.3 | 5.2 | 15.3 | 7.9 | 2.6 | ||

| Widowed | 1.3 | 7.9 | 21.9 | 12.7 | 34.6 | 59.7 | ||

| Medical History (%) | ||||||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 2.6 | 12.7 | 27.2 | <0.001 | 3.2 | 10.8 | 18.9 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 56.2 | 78.7 | 79.7 | <0.001 | 69.8 | 85.5 | 83.3 | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 7.94 | 20.1 | 37.9 | <0.001 | 17.5 | 25.9 | 36.9 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 21.0 | 45.1 | 37.3 | <0.001 | 37.0 | 52.4 | 32.6 | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 4.51 | 10.7 | 20.6 | <0.001 | 8.5 | 12.1 | 13.7 | 0.17 |

| AMI characteristics (%) | ||||||||

| Initial | 72.3 | 63.9 | 56.1 | <0.001 | 71.9 | 66.3 | 62.3 | 0.05 |

| Q-wave | 34.9 | 20.5 | 9.3 | <0.001 | 21.7 | 12.1 | 15.2 | 0.03 |

| STEMI | 50.9 | 40.6 | 17.7 | <0.001 | 33.9 | 24.1 | 24.7 | 0.04 |

| Pre-hospital delay (hr), median | ||||||||

| (IQR) | 1.78(1.00–4.42) | 2.00(1.00–3.50) | 2.00(1.00– 4.33) | <0.001 | 1.83(1.00–4.00) | 2.00 (1.17– 4.25) | 2.08(1.20 – 4.43) | <0.001 |

| Clinical parameters on admission, median (IQR) | ||||||||

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 80 ( 68 – 92 ) | 80 ( 68 – 100 ) | 80 ( 68 – 100 ) | <0.001 | 85.5 ( 72 – 98 ) | 84(69.5 – 106 ) | 88 (75 – 104 ) | <0.001 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 140(120 – 162) | 143(119– 162 ) | 138 (117– 157) | 0.203 | 142 (120 – 167 ) | 144 (123 – 174) | 139(118 – 162 ) | 0.20 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 83 ( 71 – 97 ) | 78 ( 66 – 92 ) | 72 ( 60 – 84 ) | <0.001 | 76 ( 63 – 90 ) | 75 ( 62 – 89 ) | 69 ( 56 – 83 ) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.9 (25.8–32.5) | 27.8(24.4–31.1) | 25.8 (23.1–28.3) | <0.001 | 28.3(24. 9–32.9) | 28.9(23.4–32.6) | 25.4(22.3– 28.9) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory findings on admission, median (IQR) | ||||||||

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 179(154 –208 ) | 158(137– 193 ) | 152(126 – 180) | <0.001 | 180(157 – 216 ) | 164(136 –201 ) | 168(142– 201) | <0.001 |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 115( 89 – 140) | 96 ( 74 – 119 ) | 91 ( 67 – 116 ) | <0.001 | 106(83.5 – 134 ) | 96 ( 70 – 128 ) | 98 (75 – 127 ) | <0.001 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 130 (112 – 170 ) | 157(117– 214 ) | 150(119 – 207 ) | <0.001 | 149(113 – 219 ) | 167(125 – 242 ) | 153 (122 – 212 ) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.1 ( 0.9 – 1.2 ) | 1.2 ( 1.0 – 1.5 ) | 1.4 ( 1.1 – 1.8 ) | <0.001 | 0.9 ( 0.8 – 1.2 ) | 1.1 ( 0.9 – 1.3 ) | 1.2 ( 1.0 – 1.6 ) | <0.001 |

| Length of stay (day), median | ||||||||

| (IQR) | 3.0(2.0 – 4.0 ) | 4.0 (3.0 – 7.0 ) | 4.0( 3.0 – 7.0) | <0.001 | 4.0 ( 2.5 – 5.0 ) | 5.0 ( 3.0 – 8.0 ) | 5.0 ( 3.0 – 7.0 ) | <0.001 |

IQR: inter-quartile range; BP, blood pressure; BMI, body mass index; EF, LDL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement: There is no conflict of interest for any of the authors. All authors had access to the data and had a role in writing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, et al. Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2388–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heidenreich PA, McClellan M. Trends in treatment and outcomes for acute myocardial infarction: 1975–1995. Am J Med. 2001;110:165–174. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00712-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogers WJ, Frederick PD, Stoehr E, et al. Trends in presenting characteristics and hospital mortality among patients with ST elevation and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction from 1990 to 2006. Am Heart J. 2008;156:1026–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruiz-Bailen M, Aguayo de Hoyos E, Ramos-Cuadra JA, et al. Influence of age on clinical course, management and mortality of acute myocardial infarction in the Spanish population. Int J Cardiol. 2002;85:285–296. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00187-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldberg RJ, McCormick D, Gurwitz JH, et al. Age-related trends in short- and long-term survival after acute myocardial infarction: a 20-year population-based perspective (1975–1995) Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:1311–1317. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00633-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaccarino V, Parsons L, Every NR, Barron HV, Krumholz HM. Sex-based differences in early mortality after myocardial infarction. National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2 Participants. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:217–225. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907223410401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heer T, Schiele R, Schneider S, et al. Gender differences in acute myocardial infarction in the era of reperfusion (the MITRA registry) Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:511–517. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowker TJ, Turner RM, Wood DA, et al. A national Survey of Acute Myocardial Infarction and Ischaemia (SAMII) in the U.K.: characteristics, management and in-hospital outcome in women compared to men in patients under 70 years. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:1458–1463. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radovanovic D, Erne P, Urban P, et al. Gender differences in management and outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes: results on 20,290 patients from the AMIS Plus Registry. Heart. 2007;93:1369–1375. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.106781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrikopoulos GK, Tzeis SE, Pipilis AG, et al. Younger age potentiates post myocardial infarction survival disadvantage of women. Int J Cardiol. 2006;108:320–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demirovic J, Blackburn H, McGovern PG, et al. Sex differences in early mortality after acute myocardial infarction (the Minnesota Heart Survey) Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:1096–1101. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80737-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alfredsson J, Stenestrand U, Wallentin L, Swahn E. Gender differences in management and outcome in non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome. Heart. 2007;93:1357–1362. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.102012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaccarino V, Parsons L, Peterson ED, et al. Sex differences in mortality after acute myocardial infarction: changes from 1994 to 2006. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1767–1774. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg RJ, Gore JM, Alpert JS, Dalen JE. Recent changes in attack and survival rates of acute myocardial infarction (1975 through 1981). The Worcester Heart Attack Study. Jama. 1986;255:2774–2779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldberg RJ, Gorak EJ, Yarzebski J, et al. A communitywide perspective of sex differences and temporal trends in the incidence and survival rates after acute myocardial infarction and out-of-hospital deaths caused by coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1993;87:1947–1953. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.6.1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Floyd KC, Yarzebski J, Spencer FA, et al. A 30-year perspective (1975–2005) into the changing landscape of patients hospitalized with initial acute myocardial infarction: Worcester Heart Attack Study. Circulation CQO. 2009;2:88–95. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.811828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldberg RJ, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, Wu J, Gore JM. Recent trends in the incidence rates of and death rates from atrial fibrillation complicating initial acute myocardial infarction: a community-wide perspective. Am Heart J. 2002;143:519–527. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.120410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spencer FA, Meyer TE, Goldberg RJ, et al. Twenty year trends (1975–1995) in the incidence, in-hospital and long-term death rates associated with heart failure complicating acute myocardial infarction: a community-wide perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:1378–1387. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00390-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldberg RJ, Samad NA, Yarzebski J, et al. Temporal trends in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1162–1168. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904153401504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saczynski JS, Lessard D, Spencer FA, et al. Declining length of stay for patients hospitalized with AMI: impact on mortality and readmissions. Am J Med. 123:1007–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spencer FA, Goldberg RJ, Frederick PD, et al. Age and the utilization of cardiac catheterization following uncomplicated first acute myocardial infarction treated with thrombolytic therapy (The Second National Registry of Myocardial Infarction [NRMI-2]) Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:107–111. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01602-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rogers WJ, Canto JG, Lambrew CT, et al. Temporal trends in the treatment of over 1.5 million patients with myocardial infarction in the US from 1990 through 1999: the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 1, 2 and 3. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:2056–2063. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00996-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fornasini M, Yarzebski J, Chiriboga D, et al. Contemporary trends in evidence-based treatment for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 2010;123:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Champney KP, Frederick PD, Bueno H, et al. The joint contribution of sex, age and type of myocardial infarction on hospital mortality following acute myocardial infarction. Heart. 2009;95:895–899. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.155804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosengren A, Spetz CL, Koster M, et al. Sex differences in survival after myocardial infarction in Sweden; data from the Swedish National Acute Myocardial Infarction Register. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:314–322. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahon NG, McKenna CJ, Codd MB, et al. Gender differences in the management and outcome of acute myocardial infarction in unselected patients in the thrombolytic era. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85:921–926. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00902-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]