SYNOPSIS

Structural interventions have been defined as those prevention interventions that include physical, social, cultural, organizational, community, economic, legal, and policy factors. In an effort to examine the feasibility, evaluability, and sustainability of structural interventions for HIV prevention, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention implemented a project that involved asking experts in HIV prevention and other areas of public health—including injury and violence prevention, tobacco control, drug abuse, and nutrition—to provide input on the identification of structural interventions based on the aforementioned definition. The process resulted in a list of 123 interventions that met the definition. The experts were asked to group these interventions into categories based on similarity of ideas. They were also asked to rate these interventions in terms of impact they would have, if implemented, on reducing HIV transmission. The findings highlight the need for conducting further research on structural interventions, including feasibility of implementation and effectiveness of reducing HIV transmission risks.

Worldwide, 33.4 million people are now living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). About 2.7 million people were newly infected with the virus in 2008. The total number of people living with HIV in 2008 was more than 20% higher than the number in 2000, and the prevalence was roughly threefold higher than in 1990.1 During the late 1990s, after the introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy, the numbers of new acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) cases and deaths among adults and adolescents declined substantially. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC's) HIV prevention activities during the past two decades have focused on helping uninfected people at higher risk of acquiring HIV to change and maintain behaviors to keep them uninfected. Despite the success of these efforts in reducing HIV incidence in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the number of new HIV infections was estimated to be 55,400 per year for 2003–2006.2

A wide range of effective interventions is currently available to reduce transmission of HIV/AIDS. However, most of these HIV prevention interventions focus on changing individual risk behaviors.3 Long-term, sustainable risk reduction may require taking into account factors that are external to the individual.4 HIV prevention programs need to address the contexts in which people live; that is, larger, external factors that may influence risk-taking behaviors. Very few of the available HIV prevention interventions address larger structural or environmental factors that either facilitate or impede behavior change. This article describes a process that was undertaken to identify a range of interventions that can be defined as structural, and to examine the feasibility of implementation and their perceived impact if implemented. It was proposed that such interventions could inform CDC policy development and potential program expansion.

Social and economic factors as well as laws and policies affect the transmission and differential distribution of HIV/AIDS.5 This perspective emphasizes social conditions as determinants of disease.4,5 Structural interventions promote health by altering the structural context within which health is produced.4,6 Structural interventions have been defined as HIV prevention interventions that include physical, social, cultural, organizational, community, economic, legal, and policy factors.7

Research has highlighted the role of structural factors that either facilitate behavior change or act as barriers to risk reduction.8,9 These factors either directly or indirectly affect an individual's ability to reduce the risk of getting infected or assist in changing behaviors. For example, stable housing for HIV-positive individuals was associated with changes in risk behaviors. Changes in housing status significantly reduced the risks of drug use, needle use, needle sharing, and unprotected sex.10 Similarly, uninterrupted insurance coverage, as a structural intervention, had shown strong and positive effects on the use of ambulatory care and antiretroviral therapy.11 In recent years, conditional cash transfer programs have focused on changing health behaviors such as smoking cessation, weight loss, and, more recently, promotion of HIV/AIDS prevention.12 Examination of social and environmental factors that influence risks suggests that modifying these social environmental factors may facilitate risk reduction by the individuals and also provide justification for developing intervention approaches tailored to specific determinants of risks.13,14 Successful structural and environmental public health interventions in other domains include taxation on cigarettes, as well as helmet and seat belt laws. Public policy may play a role in shaping environmental outcomes to stem HIV transmission.15

A recent study identified strategies for HIV prevention by collecting the opinions of behavioral scientists who have conducted research in the area of HIV prevention in the U.S.16 In this article, we describe a similar process that was undertaken in 2003 to identify structural interventions for HIV prevention, explore the perceived feasibility of implementing these identified interventions, and estimate the impact these interventions would have on HIV transmission. This process incorporates views and suggestions about structural interventions from a large number of experts in the field of HIV prevention. The identification of interventions was based on a specific definition of structural intervention. Structural interventions are those that address physical, social, cultural, organizational, community, economic, legal, or policy aspects of the environment. The methodology allowed the experts to contribute to this process and facilitated the inclusion of a wide range of interventions.

APPROACH

The process involved utilizing a methodology termed “concept mapping.” Concept mapping is a mixed-methods planning and evaluation approach that integrates familiar qualitative group processes (e.g., brainstorming and pile sorting) with multivariate statistical analyses to help a group describe its ideas on any topic of interest and represent these ideas visually through a map.17–19 The process typically requires the participants to brainstorm a large set of statements relevant to the topic of interest, individually sort these statements into piles of similar ones, rate each -statement on one or more dimensions, and interpret the maps that result from the data analyses. The analyses typically include multidimensional scaling (MDS) of the sort data, hierarchical cluster analysis of the MDS coordinates, and computation of average ratings for each statement and cluster of statements. The resulting maps show the individual statements in two-dimensional (x,y) space with more similar statements located closer to each other and grouped into clusters. Participants are actively involved in interpreting the results to ensure that the maps are understandable and labeled in a meaningful way. Concept mapping has been used effectively to address substantive issues across a wide range of fields.20–25

Data collection

Data were collected in a number of steps. First, a working group was formed that included representatives from CDC and a number of subject-matter experts affiliated with various research institutes. These experts had conducted research in this area and had been promoting the need for developing and implementing structural interventions for HIV prevention.

Second, the working group identified 239 stakeholders and subject-matter experts from a broad range of disciplines and regions of the U.S. The stakeholders and subject-matter experts were identified and selected based on their knowledge, expertise, and involvement in HIV prevention research and program activities and structural interventions. As the stakeholders were identified based on their knowledge and expertise, many of them came from outside the U.S., both from developed and developing countries. It was also decided that most participants needed to be representatives of the HIV prevention community, such as state and local health departments, community-based organizations, academic and research institutes, and state and federal government agencies, including CDC. Participants outside the field of HIV/AIDS, such as cancer prevention and tobacco control, were also included to generate ideas that were found to be useful in non-HIV areas. It was expected that individuals outside HIV prevention would bring new perspectives to the field.

Third, the working group developed a focused prompt, namely: “Structural factors associated with HIV transmission may include physical, social, cultural, organizational, community, economic, legal, or policy aspects of the environment. To address these structural factors, a specific action (e.g., project, intervention, or social change) that has been or could be taken to reduce HIV transmission is. …”

Fourth, the stakeholders and subject-matter experts were invited to participate in the project and contribute to its development and implementation. Stakeholders and subject-matter experts were asked to provide ideas and/or lists of interventions that would meet the previously described definition. They were provided with a Web address on which they could submit their intervention/project/action ideas online. They were asked to generate as many statements as possible and enter them into the system. The participants had eight weeks to respond to our request. During this eight-week period, they had the option of generating and entering statements in more than one session. Recognizing that the participants' locations and access to technology varied, the project enabled multiple ways to submit ideas—for example, using a fax-back form or mail. This process resulted in the generation of 393 statements from an estimated 75 different participants. Because the brainstorming was anonymous, the estimate was based on Web traffic patterns. Each statement represented an action, an intervention, or a project.

Finally, after receiving the statements, a smaller number of working group members met and reviewed each statement to edit, consolidate, eliminate redundancy, and minimize any confusion in meaning. Editing and consolidation were necessary to sort and rate the statements. The following criteria were used to generate a final set of statements:

Relevance to the stated focus question or within the scope of the question at hand;

Redundancy; and

Clarity of meaning.

The goal was to have a set of mutually exclusive statements, with only one main idea in each and with no loss of content from the original list. This process generated a final list of 123 statements. Statements that were considered too broad, nonspecific, and general in terms of their relevance to the focus statement (e.g., “end racism, homophobia, and gender inequality”) were not included in the final list of statements. These statements identified a social injustice without identifying a strategy by which to address that social injustice. In addition, such goals may not be seen by the public as falling within the appropriate range of action for public health.4 Homophobia and racism fall under this category.

Sorting and rating

After editing and consolidation were complete, a smaller group of stakeholders (70/239) volunteered to log on to another Web page for sorting and rating. They were asked to organize or sort the final list of statements (n=123) into groups or clusters based on similarity of ideas. They were also asked to provide a brief label that summarized the contents of each of their groups/clusters. The individual interventions were grouped into 11 categories based on similarity of concepts.

Next, 169 stakeholders from the original list of 239 volunteered to rate the 123 statements on a 1-to-5 scale of both feasibility and impact upon HIV incidence that these structural interventions might have if implemented. Considering the political context, capacity, and resources, they were asked to examine the feasibility of implementing the intervention within five to 10 years on a scale of 1–5, where 1 = no feasibility and 5 = very strong feasibility, and to determine how much of an impact they thought it would have, if implemented, on curbing the HIV epidemic, where 1 = no impact and 5 = very strong impact. Impact and feasibility scores were perceived by the project participants and not necessarily based on any empirical findings. The mean impact scores varied widely from 2.92 to 4.13. The stakeholders had the option of completing the task using the dedicated website, or by faxing back a form sent to them.

Data analyses

We used Concept Systems, Inc., software to analyze the data.26 We used MDS and hierarchical cluster analyses to detect dimensions that would allow us to explain observed similarities or dissimilarities (distances) between the objects and help us find relatively homogenous clusters of cases based on measured characteristics. MDS is a statistical technique for displaying differences between items, as if they were points on a map or in a three-dimensional space. The greater the distance, the more different the items are in the opinions of people who rate them. This statistical technique is used for perceptual mapping. Hierarchical cluster analysis is a statistical method for finding relatively homogeneous clusters of cases based on measured characteristics. This data-reduction technique starts with each case in a separate cluster and then combines the clusters sequentially, reducing the number of clusters at each step until only one cluster is left.

The analysis used the sorted information, discussed previously, to construct an NxN binary, symmetric matrix of similarities, for all sorting participants. We analyzed the total similarity matrix using non-metric MDS analysis with a two-dimensional solution. The solution yielded a configuration in which statements grouped together most often by the participants were located more closely in a two-dimensional space than those grouped together less frequently. The configuration resulting from the MDS analysis was the input for the hierarchical cluster analysis. To determine the best fitting cluster solution, the analysts examined a range of possible cluster solutions suggested by the analysis, and took into account the fit of the contents within clusters, as well as the specific desired uses of the results in planning and action development. Lists were developed of interventions that scored above-average ratings on feasibility and impact. All values above the group mean were considered to be high.

FINDINGS

In the following sections, we present some of the findings related to the project. Of the stakeholders, 64 provided information on types of work including types of organization and where they were located. The majority (n=40) worked on U.S. domestic HIV/AIDS issues, and 11 of the stakeholders were based in the U.S. but worked internationally. Types of organizations where they worked varied from academic institutions to state and local government.

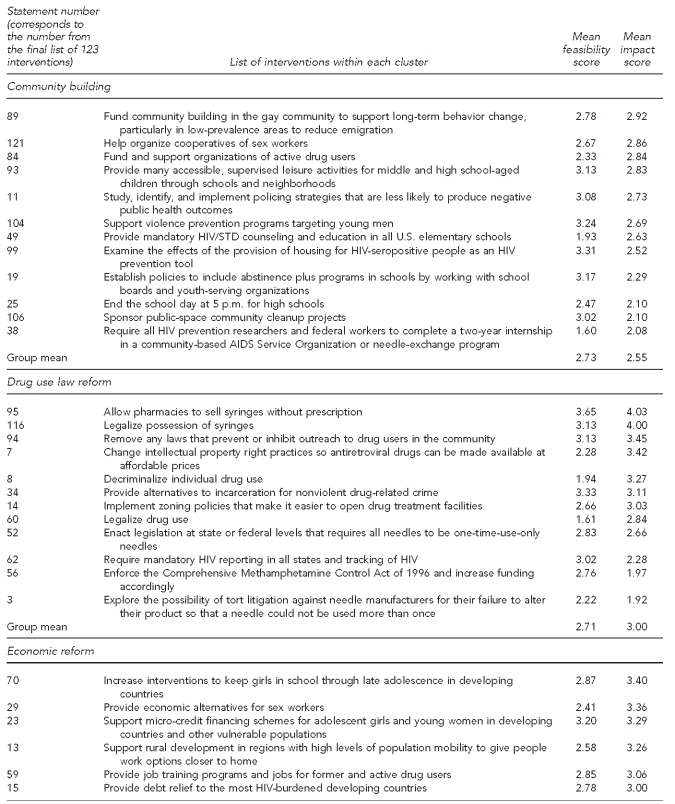

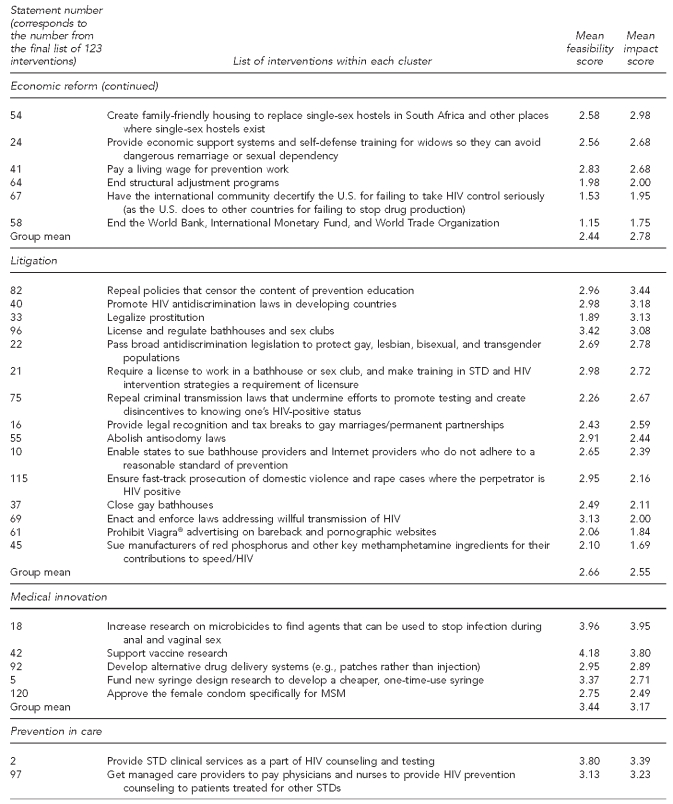

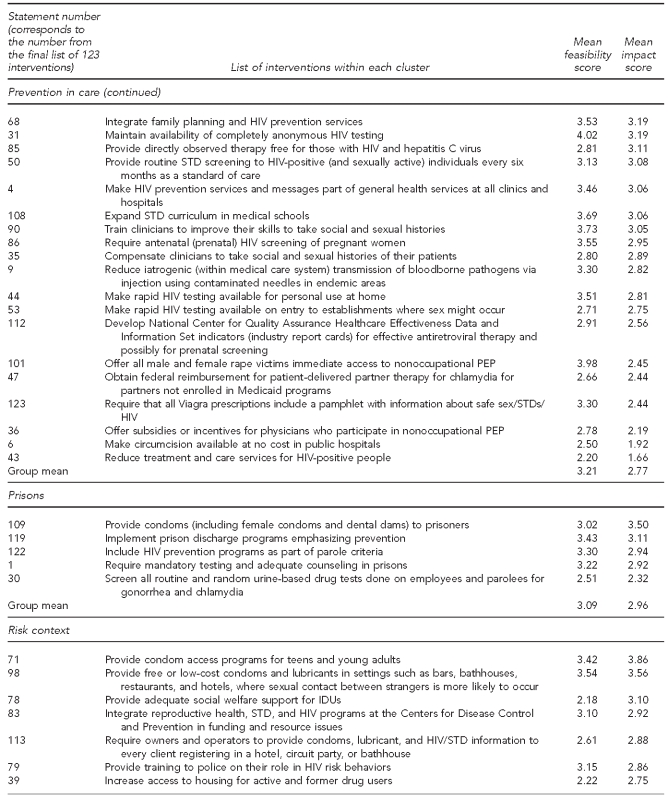

In terms of the findings related to the interventions, we first present the final list of 123 interventions categorized into 11 clusters along with the feasibility and impact rating scores of each intervention, as well as mean rating scores of each cluster (group) of interventions. Second, we present the list of 11 interventions with the highest mean feasibility and impact score within each cluster.

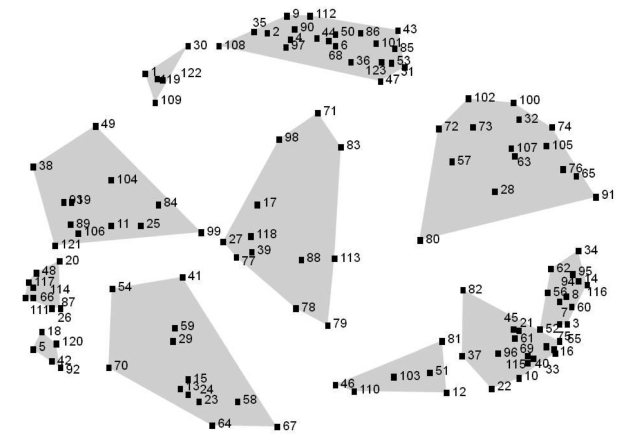

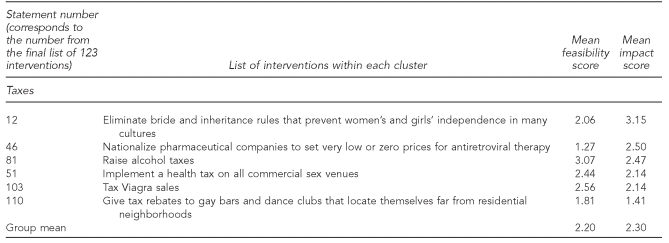

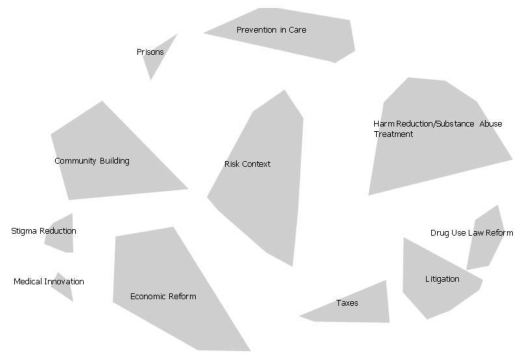

Point-cluster map

The point-cluster map (Figure 1) shows the distribution of all 123 statements (Table) in relation to each other, as arranged by MDS. The numbers on the map correspond to the statement numbers listed in the Table. Points that are closer together are similar in meaning. There are 11 clusters based on sorting conducted by the participants. Each cluster consists of items that contribute to a common theme. Based on types of statements that are grouped together, these 11 clusters have been labeled according to the contents of the clusters (Figure 2). The labels are subjective, as they have been selected based on similarity of concepts within the statement clusters. The shape and size of the clusters reflect the breadth or specificity of the clusters, with large clusters typically covering more area than smaller clusters. For example, harm reduction/substance abuse treatment is relatively broad in meaning because there is a wider disbursement of points within the cluster. On the other hand, medical innovation is a relatively tightly defined cluster as indicated by the relative proximity of the statements within the cluster.

Figure 1.

Concept map of statements in 11 clusters, with similarity of statements according to participants' sorting results indicated by proximity, in a study of structural interventions for HIV/AIDS prevention, 2003

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

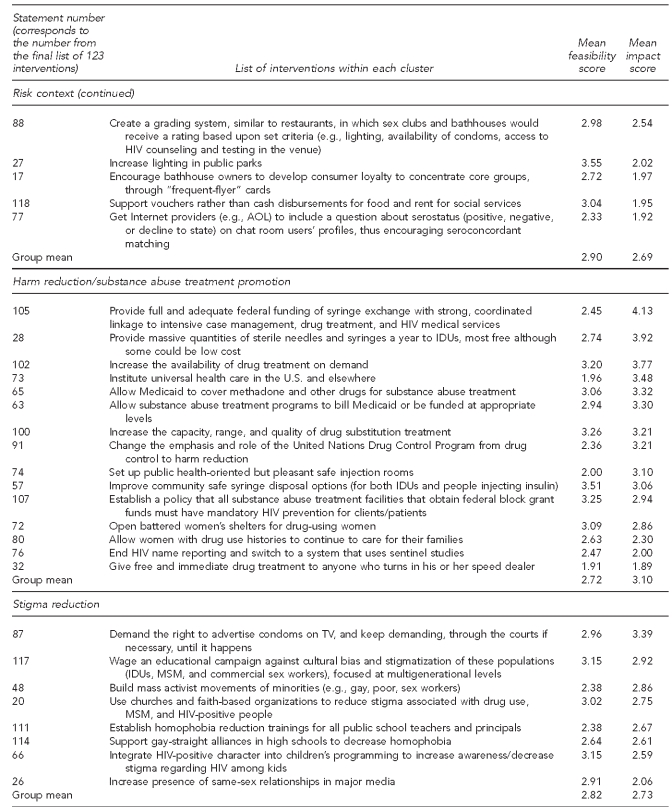

Table.

List of interventions proposed by participants in a study of structural interventions for HIV/AIDS prevention, categorized within each cluster with mean feasibility and impact scores, 2003a

a1 = no impact and 5 = very strong impact

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

STD = sexually transmitted disease

PEP = postexposure prophylaxis

IDU = injection drug user

MSM = men who have sex with men

Figure 2.

Concept map of 11 clusters with labels,a in a study of structural interventions for HIV/AIDS prevention, 2003

aClusters represent higher-order concepts derived from the contents of each map. Labels were suggested by participants and finalized by the project team.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

Rating scores of interventions

The Table provides the list of interventions within each cluster as well as the mean feasibility and impact scores. Within the community-building cluster, examining the effects of the provision of housing for HIV-seropositive people as an HIV prevention tool is considered to have high feasibility of implementation. On the other hand, within the medical innovation cluster, supporting vaccine research and increasing research on microbicides have the highest rating in terms of both feasibility and impact. Similarly, within the prevention-in-care cluster, 11 interventions received scores equal to or higher than the mean feasibility score, and 13 interventions received scores equal to or higher than the mean impact score. For the prison cluster, four interventions received scores higher than the total mean feasibility score and two interventions received scores higher than the total mean impact score.

The Table also shows that medical innovation had the highest mean scores in terms of feasibility and impact. Taxes had the lowest feasibility and impact rating, which may indicate that interventions that are within the medical/clinical arena would be feasible to implement and would have the highest impact on curbing the HIV epidemic. On the other hand, raising alcohol, Viagra®, and commercial sex venue taxes may not be feasible and, if implemented, would have the least impact on curbing the HIV epidemic.

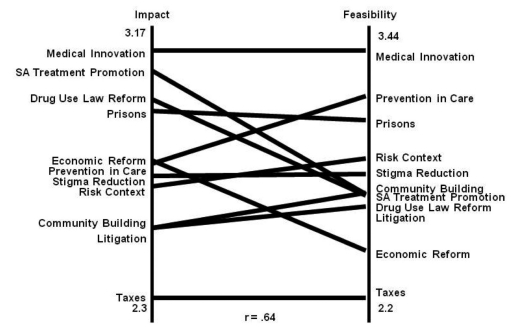

Comparing impact with feasibility

In Figure 3, each cluster is arrayed on a vertical number line for feasibility and on another vertical line for impact. The mean impact score of some of the clusters was higher than the mean feasibility score of those clusters. This finding indicates that interventions within these clusters, if implemented, would have high impact; however, they would not be feasible to implement. On the other hand, the mean feasibility score of some of the clusters was higher than the mean impact score of those clusters. A few of the clusters had similar mean impact and feasibility scores.

Figure 3.

Pattern matching comparing participant ratingsa at the cluster level with the importance of participant ratings on feasibility in a study of structural interventions for HIV/AIDS prevention, 2003b

aThe scoring system ranged from 1 to 5, where 1 = no impact and 5 = very strong impact.

bThe location of the title and the corresponding line indicate the relationship of the ratings on each cluster.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

SA = substance abuse

DISCUSSION

This project stimulated ideas from subject-matter experts around structural interventions that might be studied and eventually implemented to reduce HIV incidence. The findings presented in this article provide a suggested list of structural interventions for HIV intervention that may be studied and implemented should they be both feasible and efficacious at reducing HIV incidence. The concept mapping technique also outlined a general taxonomy of these structural interventions. The project also attempted to determine those structural interventions with the greatest perceived impact on HIV incidence that would also be feasible to implement.

Limitations

We attempted to identify and highlight structural interventions that may have significant impact in terms of reducing HIV transmission if implemented; however, our study also had a number of limitations. A total of 239 subject-matter experts representing a range of related fields and relevant agencies were identified. Of these, 75 volunteered to participate in the idea-generation process, 70 volunteered to participate in the concept-sorting process, and 169 volunteered to participate in the rating of statements in regard to perceived feasibility and impact. Because a volunteer could participate in all three steps, their opinions would be weighted more heavily in the final products of the process than those volunteers who participated in only one or two of the procedural steps in this methodology. The experts did not have to explain why they perceived something to be feasible and would have high impact. The responses could be biased based on the expertise and experiences of the experts. Most of the concepts have never been implemented and, thus, expert opinions regarding feasibility and impact were admittedly subjective.

Even though every effort was made to invite and include subject-matter experts from countries outside the U.S., the majority of the participants were -U.S.-based and, thus, the suggested structural interventions may be more applicable to the United States or other industrial nations. Most of the interventions identified and highlighted also reflected U.S. experiences that were individual, focused services within existing institutions and structures and not larger, social structural changes. While the final list of interventions generated through this process highlights the importance of identifying and possibly implementing these interventions, a number of issues need to be considered before any of these interventions could be recommended for implementation. Prior to the selection of any of the interventions, it would be necessary to consider the feasibility of implementation, including both operational and policy challenges, availability of resources to implement and sustain the interventions, and possible implications when the interventions are implemented.

CONCLUSIONS

Further research will be needed to assess the feasibility and effectiveness of some of these identified interventions. Findings from these studies and programmatic efforts will help identify appropriate structural interventions that will be feasible to implement, sustainable, and lead to further prevention of HIV transmission.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mary Kane from Concept Systems Inc., for her assistance with the implementation of the project as well as the use of the concept mapping software.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.UNAIDS/World Health Organization. Global summary of the AIDS epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, Prejean J, An Q, Lee LM, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:520–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyles CM, Kay LS, Crepaz N, Herbst JH, Passin WF, Kim AS, et al. Best-evidence interventions: findings from a systematic review of HIV behavioral interventions for US populations at high risk, 2000-2004. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:133–43. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.076182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:590–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poundstone KE, Strathee SA, Celentano DD. The social epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Epidemiol Rev. 2004;26:22–35. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blankenship KM, Friedman SR, Dworkin S, Mantell JE. Structural interventions: concepts, challenges and opportunities for research. J Urban Health. 2006;83:59–72. doi: 10.1007/s11524-005-9007-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sumartojo E. Structural factors in HIV prevention: concepts, examples, and implications for research. AIDS. 2000;14(Suppl 1):S3–10. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhodes T, Mikhailova L, Sarang A, Lowndes CM, Rylkov A, Khutorskoy M, et al. Situational factors influencing drug injecting, risk reduction and syringe exchange in Togliatti City, Russian Federation: a qualitative study of micro risk environment. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:39–54. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00521-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rhodes T, Singer M, Bourgois P, Friedman SR, Strathdee SA. The social structural production of HIV risk among injecting drug users. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:1026–44. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aidala A, Cross JE, Stall R, Harre D, Sumartojo E. Housing status and HIV risk behaviors: implications for prevention and policy. AIDS Behav. 2005;9:251–65. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9000-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riley ED, Moore KL, Haber S, Neilands TB, Cohen J, Kral AH. Population-level effects of uninterrupted health insurance on service use among HIV-positive unstably housed adults. AIDS Care. 2011;23:822–30. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.538660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kohler HP, Thornton R. Ann Arbor (MI): University of Michigan; 2010. Sep, Conditional cash transfers and HIV/AIDS prevention: unconditionally promising? [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tawil O, Verster A, O'Reilly KR. Enabling approaches for HIV/AIDS prevention: can we modify the environment and minimize the risk? AIDS. 1995;9:1299–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta GR, Parkhurst JO, Ogden JA, Aggleton P, Mahal A. Structural approaches to HIV prevention. Lancet. 2008;372:764–75. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60887-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sweat MD, Denison JA. Reducing HIV incidence in developing countries with structural and environmental interventions. AIDS. 1995;9(Suppl A):S251–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Copenhaver MM, Fisher JD. Experts outline ways to decrease the decade-long yearly rate of 40,000 new HIV infections in the US. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:105–14. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trochim WM, Linton R. Conceptualization for planning and evaluation. Eval Program Plann. 1986;9:289–308. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(86)90044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trochim WMK. An introduction to concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Eval Program Plann. 1989;1:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greene JC, Caracelli VJ. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1997. Advances in mixed-method evaluation: the challenges and benefits of integrating diverse paradigms: new directions for evaluations, no 74. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trochim WM, Milstein B, Wood BJ, Jackson S, Pressler V. Setting objectives for community and systems change: an application of concept mapping for planning a statewide health improvement initiative. Health Promot Pract. 2004;5:8–19. doi: 10.1177/1524839903258020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLinden DJ, Trochim WMK. Getting to parallel: assessing the return on expectations of training. Perfomance Improvement. 1998;37:21–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shern DL, Trochim WMK, LaComb CA. The use of concept mapping for assessing fidelity of model transfer: an example from pysychiatric rehabilitation. Eval Program Plan. 1995;18:143–53. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trochim WMK. Concept mapping: soft science or hard art? Eval Program Plan. 1989b;12(Special Issue):87–110. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trochim WMK, Cook JA, Setze RJ. Using concept mapping to develop a conceptual framework of staff's views of a supported employment program for individuals with severe mental illness. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:766–75. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.4.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Witkin BR, Trochim WMK. Toward a synthesis of listening constructs: a concept map analysis of the construct of listening. Int J Listening. 1997;11:69–87. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Concept Systems Inc. Concept Systems: Version 1.75. Ithaca (NY): Concept Systems, Inc.; 2002. [Google Scholar]